Consumption of Alcohol, Cannabis, and Tobacco in a Cohort of Adolescents before and during COVID-19 Confinement

Abstract

:1. Introduction

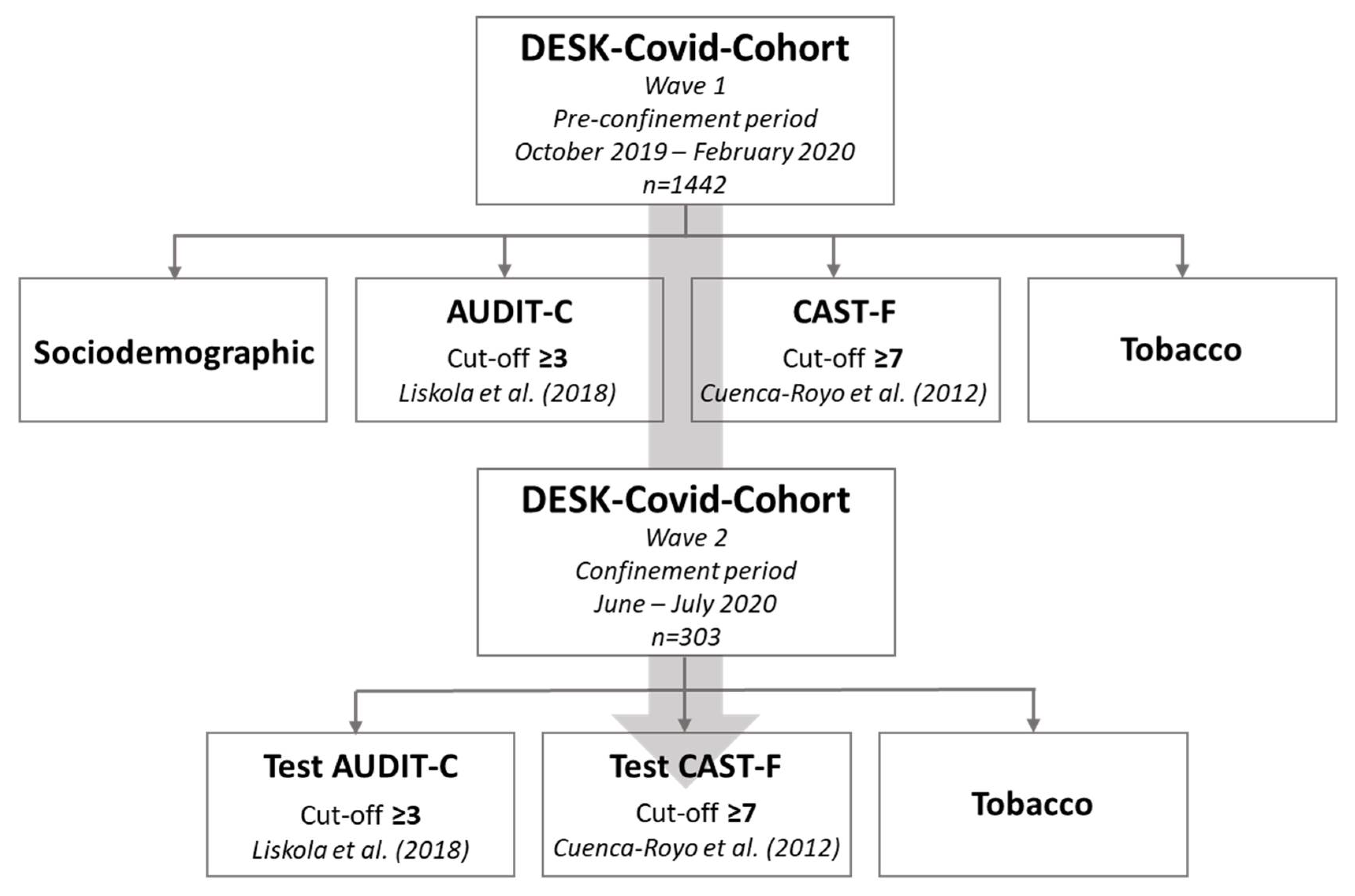

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting and Sample

2.2. DESK-COVID-Cohort Questionnaires

2.3. Measurements

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mengin, A.; Allé, M.C.; Rolling, J.; Ligier, F.; Schroder, C.; Lalanne, L.; Berna, F.; Jardri, R.; Vaiva, G.; Geoffroy, P.A.; et al. Conséquences psychopathologiques du confinement. L’Encéphale 2020, 46, S43–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bade, R.; Simpson, B.S.; Ghetia, M.; Nguyen, L.; White, J.M.; Gerber, C. Changes in Alcohol Consumption Associated with Social Distancing and Self-isolation Policies Triggered by COVID-19 in South Australia: A Wastewater Analysis Study. Addiction 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderbruggen, N.; Matthys, F.; Van Laere, S.; Zeeuws, D.; Santermans, L.; Van den Ameele, S.; Crunelle, C.L. Self-Reported Alcohol, Tobacco, and Cannabis Use during COVID-19 Lockdown Measures: Results from a Web-Based Survey. Eur. Addict. Res. 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, T.; Grey, I. Health Behaviour Changes during COVID-19 and the Potential Consequences: A Mini-Review. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedzwiedz, C.L.; Green, M.J.; Benzeval, M.; Campbell, D.; Craig, P.; Demou, E.; Leyland, A.; Pearce, A.; Thomson, R.; Whitley, E.; et al. Mental Health and Health Behaviours before and during the Initial Phase of the COVID-19 Lockdown: Longitudinal Analyses of the UK Household Longitudinal Study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumas, T.M.; Ellis, W.; Litt, D.M. What Does Adolescent Substance Use Look Like During the COVID-19 Pandemic? Examining Changes in Frequency, Social Contexts, and Pandemic-Related Predictors. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Liu, X.; Fang, Y.; Fan, B.; Fuller, C.J.; Guan, Z.; Yao, Z.; Kong, J.; Lu, J.; Litvak, I.J. Alcohol Abuse/Dependence Symptoms Among Hospital Employees Exposed to a SARS Outbreak. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008, 43, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Đogaš, Z.; Lušić Kalcina, L.; Pavlinac Dodig, I.; Demirović, S.; Madirazza, K.; Valić, M.; Pecotić, R. The Effect of COVID-19 Lockdown on Lifestyle and Mood in Croatian General Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. Croat. Med. J. 2020, 61, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Álvarez, L.; de la Fuente-Tomás, L.; Sáiz, P.A.; García-Portilla, M.P.; Bobes, J. ¿Se observarán cambios en el consumo de alcohol y tabaco durante el confinamiento por COVID-19? Adicciones 2020, 32, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawke, L.D.; Barbic, S.P.; Voineskos, A.; Szatmari, P.; Cleverley, K.; Hayes, E.; Relihan, J.; Daley, M.; Courtney, D.; Cheung, A.; et al. Impacts of COVID-19 on Youth Mental Health, Substance Use, and Well-Being: A Rapid Survey of Clinical and Community Samples: Répercussions de La COVID-19 Sur La Santé Mentale, l’utilisation de Substances et Le Bien-Être Des Adolescents: Un Sondage Rapide d’échantillons Cliniques et Communautaires. Can. J. Psychiatry 2020, 65, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, M.E.; Wightman, P.; Schoeni, R.F.; Schulenberg, J.E. Socioeconomic Status and Substance Use among Young Adults: A Comparison across Constructs and Drugs. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2012, 73, 772–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barnes, G.M.; Hoffman, J.H.; Welte, J.W.; Farrell, M.P.; Dintcheff, B.A. Effects of Parental Monitoring and Peer Deviance on Substance Use and Delinquency. J. Marriage Fam. 2006, 68, 1084–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niño, M.D.; Cai, T.; Ignatow, G. Social Isolation, Drunkenness, and Cigarette Use among Adolescents. Addict. Behav. 2016, 53, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, M.; Fisher, J.C.; Moody, J.; Feinberg, M.E. Different Kinds of Lonely: Dimensions of Isolation and Substance Use in Adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 47, 1755–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, L. The Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Risk of Youth Substance Use. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 467–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggs, J.L. Adolescent Life in the Early Days of the Pandemic: Less and More Substance Use. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 307–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap Consortium: Building an International Community of Software Platform Partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betsch, C.; Wieler, L.H.; Habersaat, K. Monitoring Behavioural Insights Related to COVID-19. Lancet 2020, 395, 1255–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Red de Vigilancia Epidemiológica de Cataluña (XVEC). Informe Técnico de Resumen de Los Casos de La COVID-19 En Cataluña; Subdirecció General de Vigilància i Resposta a Emergències de Salut Pública: Barcelona, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liskola, J.; Haravuori, H.; Lindberg, N.; Niemelä, S.; Karlsson, L.; Kiviruusu, O.; Marttunen, M. AUDIT and AUDIT-C as Screening Instruments for Alcohol Problem Use in Adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018, 188, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cuenca-Royo, A.M.; Sánchez-Niubó, A.; Forero, C.G.; Torrens, M.; Suelves, J.M.; Domingo-Salvany, A. Psychometric Properties of the CAST and SDS Scales in Young Adult Cannabis Users. Addict. Behav. 2012, 37, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeting, H.; Hunt, K. Adolescent Socioeconomic and School-Based Social Status, Smoking, and Drinking. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 57, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Espelt, A.; Mari-Dell’Olmo, M.; Penelo, E.; Bosque-Prous, M. Applied Prevalence Ratio Estimation with Different Regression Models: An Example from a Cross-National Study on Substance Use Research. Adicciones 2017, 29, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Engs, R.; Hanson, D. Gender Differences in Drinking Patterns and Problems among College Students: A Review of the Literature. JADE 1990, 35, 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Legleye, S.; Piontek, D.; Kraus, L. Psychometric Properties of the Cannabis Abuse Screening Test (CAST) in a French Sample of Adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011, 113, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donath, C.; Grässel, E.; Baier, D.; Pfeiffer, C.; Karagülle, D.; Bleich, S.; Hillemacher, T. Alcohol Consumption and Binge Drinking in Adolescents: Comparison of Different Migration Backgrounds and Rural vs. Urban Residence—A Representative Study. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McInnis, O.; Young, M.; Saewyc, E.; Jahrig, J.; Adlaf, E.; Lemaire, J.; Taylor, S.; Pickett, W.; Stephens, M.; DiGioacchino, L.; et al. Urban and Rural Student Substance Use; Canadien Centre on Substance Abuse: Ottawa, ON, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Golpe, S.; Isorna, M.; Barreiro, C.; Braña, T.; Rial, A. Binge Drinking among Adolescents: Prevalence, Risk Practices and Related Variables. Adicciones 2017, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachman, J.G.; O’Malley, P.M.; Johnston, L.D.; Schulenberg, J.E.; Wallace, J.M. Racial/Ethnic Differences in the Relationship between Parental Education and Substance Use among U.S. 8th-, 10th-, and 12th-Grade Students: Findings from the Monitoring the Future Project. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2011, 72, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.O.; Cho, J.; Yoon, Y.; Bello, M.S.; Khoddam, R.; Leventhal, A.M. Developmental Pathways from Parental Socioeconomic Status to Adolescent Substance Use: Alternative and Complementary Reinforcement. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 47, 334–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, H.A.; Noh, S.; Adlaf, E.M. Perceived Financial Status, Health, and Maladjustment in Adolescence. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 68, 1527–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fone, D.L.; Farewell, D.M.; White, J.; Lyons, R.A.; Dunstan, F.D. Socioeconomic Patterning of Excess Alcohol Consumption and Binge Drinking: A Cross-Sectional Study of Multilevel Associations with Neighbourhood Deprivation. BMJ Open 2013, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karriker-Jaffe, K.J. Areas of Disadvantage: A Systematic Review of Effects of Area-Level Socioeconomic Status on Substance Use Outcomes. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2011, 30, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galea, S.; Ahern, J.; Tracy, M.; Vlahov, D. Neighborhood Income and Income Distribution and the Use of Cigarettes, Alcohol, and Marijuana. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007, 32, S195–S202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chodkiewicz, J.; Talarowska, M.; Miniszewska, J.; Nawrocka, N.; Bilinski, P. Alcohol Consumption Reported during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Initial Stage. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plan Nacional Sobre Drogas. Encuesta Sobre Uso de Drogas en Enseñanzas Secundarias en España (ESTUDES), 1994–2018/2019; Ministerio de Sanidad: Madrid, Spain, 2020.

- Hanson, C.L.; Novilla, M.L.L.B.; Barnes, M.D.; Eggett, D.; McKell, C.; Reichman, P.; Havens, M. Using the Rural-Urban Continuum to Explore Adolescent Alcohol, Tobacco, and Other Drug Use in Montana. J. Child Adolesc. Subst. Abus. 2008, 18, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, J.; Ward, J.; Wand, H.; Byron, K.; Bamblett, A.; Waples-Crowe, P.; Betts, S.; Coburn, T.; Delaney-Thiele, D.; Worth, H.; et al. Illicit and Injecting Drug Use among Indigenous Young People in Urban, Regional and Remote Australia: Illicit Drug Use among Indigenous Young People. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2016, 35, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, M.C.; Alarcón, A.; García, F.; Gracia, E. Consumo de alcohol, tabaco, cannabis y otras drogas en la adolescencia: Efectos de la familia y el barrio. An. Psicol. 2015, 31, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total | DESK-COVID-Cohort | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | p-Value | |||

| Total | Total | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| 1442 | 100 | 303 | 100 | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Boys | 624 | 43.3 | 90 | 29.7 | <0.001 |

| Girls | 818 | 56.7 | 213 | 70.3 | |

| Course | |||||

| 4th ESO | 915 | 63.5 | 169 | 55.8 | 0.052 |

| 2nd baccalaureate | 402 | 27.9 | 104 | 34.3 | |

| VET | 120 | 8.3 | 30 | 9.9 | |

| Education level of parents | |||||

| University | 572 | 44 | 120 | 43 | 0.83 |

| Secondary | 456 | 35 | 103 | 36.9 | |

| Primary | 274 | 21 | 56 | 20.1 | |

| SEP a | |||||

| Lower SEP | 537 | 37.2 | 105 | 34.7 | 0.15 |

| Medium SEP | 464 | 32.2 | 115 | 38 | |

| Higher SEP | 441 | 30.6 | 83 | 27.4 | |

| Municipality of residence b | |||||

| Rural | 830 | 59.3 | 176 | 60.3 | 0.75 |

| Urban | 570 | 40.7 | 116 | 39.7 | |

| Impact of COVID-19 on the region c | |||||

| More affected (Anoia) | 267 | 18.5 | 54 | 17.8 | 0.78 |

| Less affected (others) | 1175 | 81.5 | 249 | 82.2 | |

| Binge drinking d | |||||

| Yes | 480 | 56.7 | 110 | 36.3 | <0.001 |

| No | 367 | 43.3 | 193 | 63.7 | |

| Hazardous drinking (AUDIT-C) | |||||

| Yes | 513 | 64.4 | 118 | 38.9 | <0.001 |

| No | 929 | 35.6 | 185 | 61.1 | |

| Hazardous consumption of cannabis (CAST) | |||||

| Yes | 81 | 5.6 | 14 | 4.6 | 0.017 |

| No | 1361 | 94.4 | 289 | 95.4 | |

| Daily smoking-Tobacco | |||||

| Yes | 156 | 10.8 | 27 | 8.9 | 0.017 |

| No | 1286 | 89.2 | 276 | 91.1 | |

| Total | Binge Drinking | Hazardous Drinking | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | During | Pre | During | |||||

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |

| 36.3 | (31.1–41.9) | 5.9 | (3.8–9.2) | 38.9 | (33.6–44.6) | 5.6 | (3.5–8.89) | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Boys | 33.3 | (24.4–43.7) | 6.7 | (3.0–14.1) | 37.8 | (28.4–48.2) | 8.9 | (4.5–16.8) |

| Girls | 37.6 | (31.3–44.3) | 5.6 | (3.2–9.7) | 39.4 | (33.1–46.2) | 4.2 | (2.2–7.9) |

| Course | ||||||||

| 4th ESO | 29.0 | (22.6–36.3) | 4.1 | (1.9–8.5) | 30.2 | (23.7–37.5) | 3.5 | (1.6–7.78) |

| 2nd baccalaureate | 44.2 | (34.9–53.9) | 6.7 | (3.2–13.5) | 50.0 | (40.5–59.5) | 6.7 | (3.2–13.5) |

| VET | 50.0 | (32.8–67.2) | 13.3 | (5.1–30.7) | 50.0 | (32.8–67.2) | 13.3 | (5.1–30.7) |

| Education level of parents | ||||||||

| University | 33.3 | (25.5–42.3) | 3.3 | (1.3–8.6) | 37.5 | (29.3–46.5) | 5.0 | (2.3–10.7) |

| Secondary | 35.0 | (26.3–44.7) | 6.8 | (3.3–13.6) | 35.9 | (27.2–45.6) | 5.8 | (2.6–12.4) |

| Primary | 44.6 | (32.2–57.8) | 7.1 | (2.7–17.6) | 44.6 | (32.2–57.8) | 7.1 | (2.7–17.6) |

| SEP | ||||||||

| Lower SEP | 33.3 | (24.9–42.9) | 4.8 | (1.9–10.9) | 32.4 | (24.1–41.9) | 2.9 | (0.9–8.5) |

| Medium SEP | 36.5 | (28.2–45.7) | 7.0 | (3.5–13.3) | 39.1 | (30.6–48.4) | 7.0 | (3.5–13.3) |

| Higher SEP | 39.8 | (29.8–50.6) | 6.0 | (2.5–13.7) | 47.0 | (36.5–57.7) | 7.2 | (3.2–15.2) |

| Municipality of residence | ||||||||

| Rural | 34.7 | (27.9–42.0) | 4.0 | (1.9–8.1) | 38.1 | (31.3–45.5) | 4.5 | (2.3–8.8) |

| Urban | 38.8 | (30.3–47.9) | 8.6 | (4.8–15.3) | 41.4 | (32.8–50.6) | 6.9 | (3.6–13.2) |

| COVID-19 impact on the region | ||||||||

| More affected (Anoia) | 40.7 | (28.5–54.2) | 3.7 | (0.9–13.7) | 42.6 | (30.2–56.0) | 5.5 | (1.8–15.9) |

| Less affected (others) | 35.3 | (29.6–41.5) | 6.4 | (3.9–10.2) | 38.2 | (32.3–44.4) | 5.6 | (3.4–9.3) |

| Total | Hazardous Consumption of Cannabis | Daily Smoking of Tobacco | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | During | Pre | During | |||||

| % | 95%CI | % | 95%CI | % | 95%CI | % | 95%CI | |

| 4.6 | (2.7–7.8) | 2.3 | (1.1–4.8) | 8.9 | (6.2–12.7) | 6.3 | (4.0–9.6) | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Boys | 2.2 | (0.6–8.5) | 2.2 | (0.6–8.5) | 4.4 | (1.7–11.3) | 5.6 | (2.3–12.7) |

| Girls | 5.6 | (3.2–9.7) | 2.3 | (1.0–5.5) | 10.8 | (7.3–15.7) | 6.6 | (3.9–10.8) |

| Course | ||||||||

| 4th ESO | 4.7 | (2.4–9.2) | 1.8 | (0.6–5.4) | 5.3 | (2.8–9.9) | 4.1 | (1.9–8.5) |

| 2nd baccalaureate | 1.9 | (0.5–7.4) | 1.9 | (0.5–7.4) | 10.6 | (5.9–18.1) | 5.8 | (2.6–12.3) |

| VET | 13.3 | (5.1–30.7) | 6.7 | (1.7–23.2) | 12.3 | (11.5–41.6) | 20 | (9.2–38.0) |

| Education level of parents | ||||||||

| University | 2.5 | (0.8–7.5) | 2.5 | (0.8–7.5) | 5.8 | (2.8–11.8) | 3.3 | (1.3–8.6) |

| Secondary | 2.9 | (0.9–8.7) | 1.0 | (0.1–6.6) | 10.7 | (5.9–18.3) | 4.9 | (2.0–11.2) |

| Primary | 12.5 | (6.2–24.0) | 3.6 | (0.9–13.2) | 8.9 | (3.8–19.8) | 10.7 | (4.9–21.9) |

| SEP | ||||||||

| Lower SEP | 3.8 | (1.4–9.7) | 3.8 | (1.4–9.7) | 10.5 | (5.9–17.9) | 6.7 | (3.2–13.4) |

| Medium SEP | 5.2 | (2.4–11.2) | 1.7 | (0.4–6.7) | 7.8 | (4.1–14.4) | 5.2 | (2.34–11.2) |

| Higher SEP | 4.8 | (1.8–12.2) | 1.2 | (0.2–8.1) | 8.4 | (4.1–16.7) | 7.2 | (3.3–15.2) |

| Municipality of residence | ||||||||

| Rural | 3.4 | (1.5–7.4) | 1.7 | (0.5–5.2) | 6.3 | (3.5–10.9) | 4.5 | (2.3–8.8) |

| Urban | 6.9 | (3.5–13.2) | 3.4 | (1.4–8.9) | 12.1 | (7.3–19.4) | 9.5 | (5.3–16.4) |

| COVID-19 impact on the region | ||||||||

| More affected (Anoia) | 9.3 | (3.9–20.4) | 1.9 | (0.3–12.2) | 5.6 | (1.8–15.9) | 7.4 | (2.8–18.2) |

| Less affected (others) | 3.6 | (1.9–6.8) | 2.4 | (1.1–5.3) | 9.6 | (6.5–13.9) | 6.0 | (3.7–9.8) |

| Total | Binge Drinking | Hazardous Drinking | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIw | 95%CI | RR | 95%CI | CIw | 95%CI | RR | 95%CI | |

| 5.94 | (3.76–9.24) | 5.61 | (3.51–8.85) | |||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Boys | 6.67 | (3.02–14.09) | 1 | 8.89 | (4.49–16.82) | 1 | ||

| Girls | 5.63 | (3.22–9.68) | 0.85 | (0.33–2.19) | 4.22 | (2.21–7.94) | 0.48 | (0.19–1.19) |

| Course | ||||||||

| 4th ESO | 4.14 | (1.98–8.45) | 1 | 3.55 | (1.59–7.70) | 1 | ||

| 2nd Baccalaureate | 6.73 | (3.23–13.48) | 1.63 | (0.59–4.51) | 6.73 | (3.23–13.48) | 1.90 | (0.65–5.49) |

| VET | 13.33 | (5.07–30.68) | 3.21 * | (1.0–10.35) | 13.33 | (5.07–30.68) | 3.76* | (1.12–12.54) |

| Education level of parents | ||||||||

| University | 3.33 | (1.25–8.61) | 1 | 5.00 | (2.25–10.71) | 1 | ||

| Secondary | 6.79 | (3.26–13.61) | 2.14 | (0.55–8.28) | 5.82 | (2.63–12.40) | 1.43 | (0.42–4.87) |

| Primary | 7.14 | (2.69–17.60) | 2.04 | (0.61–6.78) | 7.14 | (2.69–17.60) | 1.17 | (0.39–3.51) |

| SEP | ||||||||

| Lower SEP | 4.76 | (1.98–10.96) | 1 | 2.85 | (0.92–8.52) | 1 | ||

| Medium SEP | 6.95 | (3.51–13.32) | 1.46 | (0.49–4.33) | 6.95 | (3.51–13.32) | 2.43 | (0.66–8.95) |

| Higher SEP | 6.02 | (2.52–13.71) | 1.27 | (0.38–4.23) | 7.22 | (3.27–15.21) | 2.53 | (0.65–9.83) |

| Municipality of residence | ||||||||

| Rural | 3.97 | (1.90–8.12) | 1 | 4.54 | (2.28–8.84) | 1 | ||

| Urban | 8.62 | (4.68–15.31) | 2.17 | (0.85–5.54) | 6.89 | (3.47–13.22) | 1.52 | (0.58–3.93) |

| COVID-19 impact on the region | ||||||||

| More affected (Anoia) | 3.70 | (0.92–13.70) | 1 | 5.55 | (1.79–15.92) | 1 | ||

| Less affected (others) | 6.42 | (3.96–10.24) | 1.73 | (0.41–7.34) | 5.62 | (3.35–9.28) | 1.01 | (0.30–3.41) |

| Hazardous Consumption of Cannabis | Daily Smoking—Tobacco | Worsening Consumption a | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIw | 95%CI | RR | 95%CI | CIw | 95%CI | RR | 95%CI | CIw | 95%CI | RR | 95%CI | |

| Total | 2.31 | (1.10–4.77) | 6.27 | (4.02–9.63) | ||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Boys | 2.22 | (0.55–8.49) | 1 | 5.56 | (2.32–12.70) | 1 | 3.33 | (1.07–9.87) | 1 | |||

| Girls | 2.35 | 0.98–5.53) | 1.06 | (0.21–5.36) | 6.57 | (3.92–10.81) | 1.18 | (0.44–3.19) | 4.69 | (2.54–8.52) | 1.41 | (0.40–5.01) |

| Course | ||||||||||||

| 4th ESO | 1.77 | (0.57–5.38) | 1 | 4.14 | (1.98–8.45) | 1 | 3.55 | (1.59–7.69) | 1 | |||

| 2nd Baccalaureate | 1.92 | (0.47–7.40) | 1.08 | (0.18–6.39) | 5.76 | (2.61–12.28) | 1.39 | (0.48–4.04) | 4.81 | (2.01–11.06) | 1.35 | (0.42–4.33) |

| VET | 6.66 | (1.66–23.16) | 3.76 | (0.65–21.59) | 20.0 * | (9.24–38.03) | 4.83 * | (1.74–13.39) | 6.66 | (1.66–23.16) | 1.88 | (0.39–8.89) |

| Education level of parents | ||||||||||||

| University | 2.50 | (0.80–7.49) | 1 | 3.33 | (1.25–8.57) | 1 | 2.5 | (0.80–7.49) | 1 | |||

| Secondary | 0.97 | (0.13–6.16) | 1.43 | (0.24–8.33) | 4.85 | (2.02–11.17) | 3.21 | (0.94–10.96) | 5.82 | (2.63–12.4) | 1.43 | (0.24–8.33) |

| Primary | 3.57 | (0.88–13.25) | 0.39 | (0.04–3.69) | 10.71 | (4.87–21.92) | 1.46 | (0.40–5.29) | 3.57 | (0.88–13.25) | 2.33 | (0.59–9.11) |

| SEP | ||||||||||||

| Lower SEP | 3.81 | (1.43–9.74) | 1 | 6.66 | (3.20–13.36) | 1 | 5.71 | (2.58–12.17) | 1 | |||

| Medium SEP | 1.73 | (0.43–6.72) | 0.46 | (0.09–2.45) | 5.21 | (2.35–11.16) | 0.78 | (0.27–2.26) | 4.31 | (1.81–10.05) | 0.76 | (0.23–2.42) |

| Higher SEP | 1.20 | (0.16–8.11) | 0.32 | (0.04–2.79) | 7.22 | (3.27–15.21) | 1.08 | (0.38–3.11) | 2.41 | (0.60–9.17) | 0.42 | (0.09–2.04) |

| Municipality of residence | ||||||||||||

| Rural | 1.70 | (0.54–5.17) | 1 | 4.54 | (2.28–8.84) | 1 | 3.97 | (1.90–8.29) | 1 | |||

| Urban | 3.44 | (1.29–8.86) | 2.02 | (0.46–8.89) | 9.48 | (5.31–16.35) | 2.09 | (0.86–5.04) | 5.17 | (2.33–11.07) | 1.30 | (0.45–3.78) |

| COVID-19 impact on the region | ||||||||||||

| More affected (Anoia) | 1.85 | (0.25–12.08) | 1 | 7.41 | (2.79–18.19) | 1 | 5.55 | (1.79–15.92) | 1 | |||

| Less affected (others) | 2.41 | (1.08–5.27) | 1.30 | (0.16–10.63) | 6.02 | (3.65–9.76) | 0.81 | (0.28–2.36) | 4.01 | (2.16–7.31) | 0.72 | (0.21–2.54) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rogés, J.; Bosque-Prous, M.; Colom, J.; Folch, C.; Barón-Garcia, T.; González-Casals, H.; Fernández, E.; Espelt, A. Consumption of Alcohol, Cannabis, and Tobacco in a Cohort of Adolescents before and during COVID-19 Confinement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7849. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157849

Rogés J, Bosque-Prous M, Colom J, Folch C, Barón-Garcia T, González-Casals H, Fernández E, Espelt A. Consumption of Alcohol, Cannabis, and Tobacco in a Cohort of Adolescents before and during COVID-19 Confinement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(15):7849. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157849

Chicago/Turabian StyleRogés, Judit, Marina Bosque-Prous, Joan Colom, Cinta Folch, Tivy Barón-Garcia, Helena González-Casals, Esteve Fernández, and Albert Espelt. 2021. "Consumption of Alcohol, Cannabis, and Tobacco in a Cohort of Adolescents before and during COVID-19 Confinement" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 15: 7849. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157849

APA StyleRogés, J., Bosque-Prous, M., Colom, J., Folch, C., Barón-Garcia, T., González-Casals, H., Fernández, E., & Espelt, A. (2021). Consumption of Alcohol, Cannabis, and Tobacco in a Cohort of Adolescents before and during COVID-19 Confinement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(15), 7849. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157849