Effects of Group and Individual Culturally Adapted Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Depression and Sexual Satisfaction among Perimenopausal Women

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Menopausal Transition

1.2. Menopausal Transition and Sexual Satisfaction

1.3. Marital Sexual Satisfaction in Islam

1.4. CA-CBT Theoretical Framework

- (1).

- To evaluate the physical harm that continuous melancholy and depression might inflict against the need to grieve over one’s loss. In anguish over what one has lost, destroying one’s health would be equivalent to someone selling up their capital for a small profit.

- (2).

- To look around and realize that none in this world has perpetual enjoyment and happiness, none never loss of anything or anyone. The pleasures one acquires in life are merely an added gift to be enjoyed with delight, and the losses one experiences and the pleasures which one is unable to obtain should not stop one enjoying the present life with what one has.

- (3).

- To train oneself to behave and endure in the face of misfortune by imagining the worse that could have happened, what will happen when one faces a greater calamity in the future if they cannot face it now.

- (4).

- Modeling on the tales of courageous heroic people rather than succumbing to being cowardly and remain in sadness.

- (5).

- Acknowledging that the painful occurrence and the days that follow will gradually diminish the incident’s terrible effects until it is forgotten. This mental strategy will produce an immediate feeling of comfort, if not outright delight and joy.

- (1).

- Talking to someone who can bring back happiness.

- (2).

- Listening to music and songs.

- (3).

- Participating in activities that provide warm emotions.

1.5. Research Gap

1.6. Research Objectives

- There is a significant reduction in depression and improvement in sexual satisfaction in the participants of the treatment groups GCA-CBT and ICA-CBT across time (T1, T2, and T3).

- In comparison to the control group, the treatment groups remain significantly lower in depression and higher in sexual satisfaction at the follow-up time (T3).

2. Method

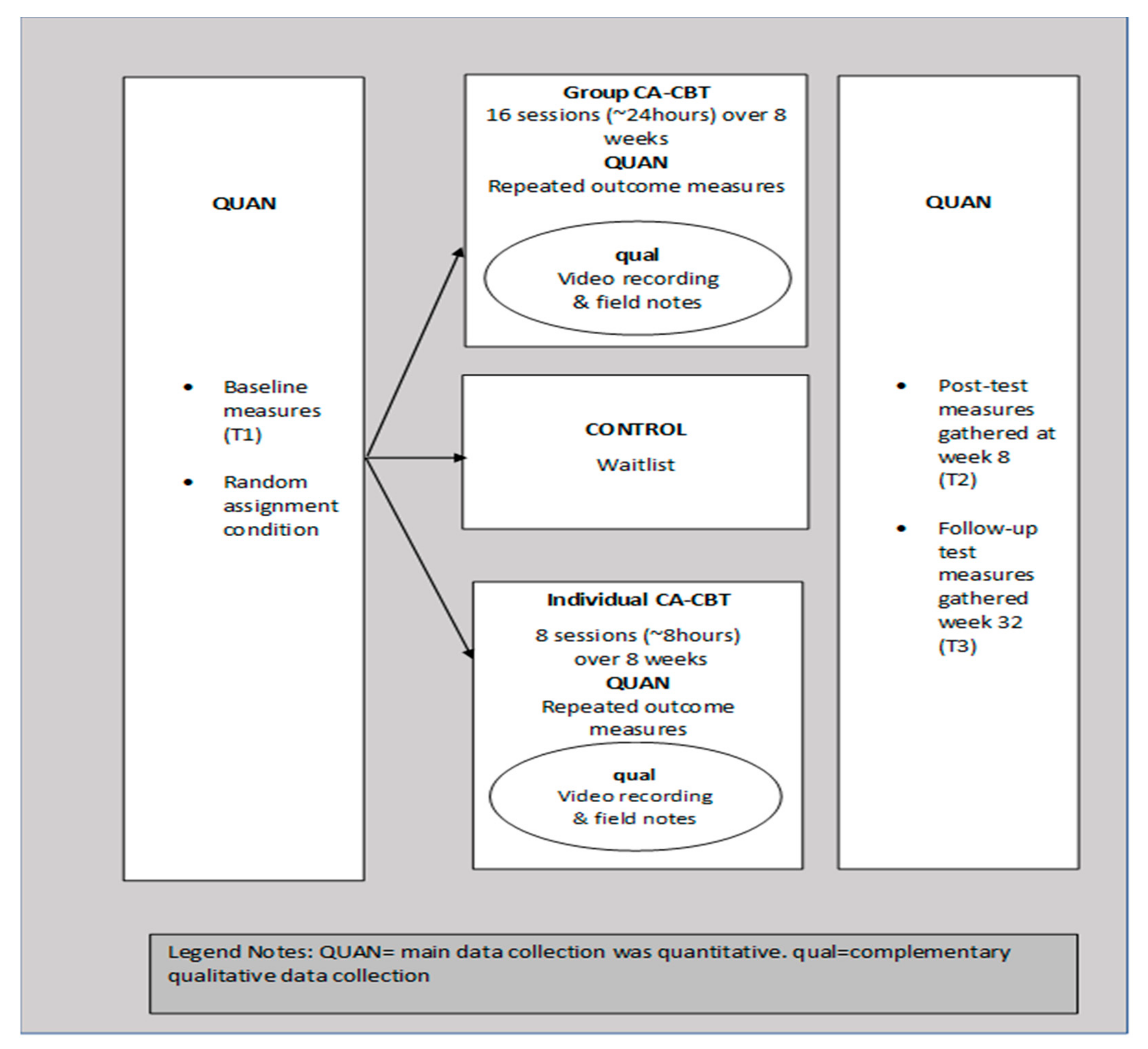

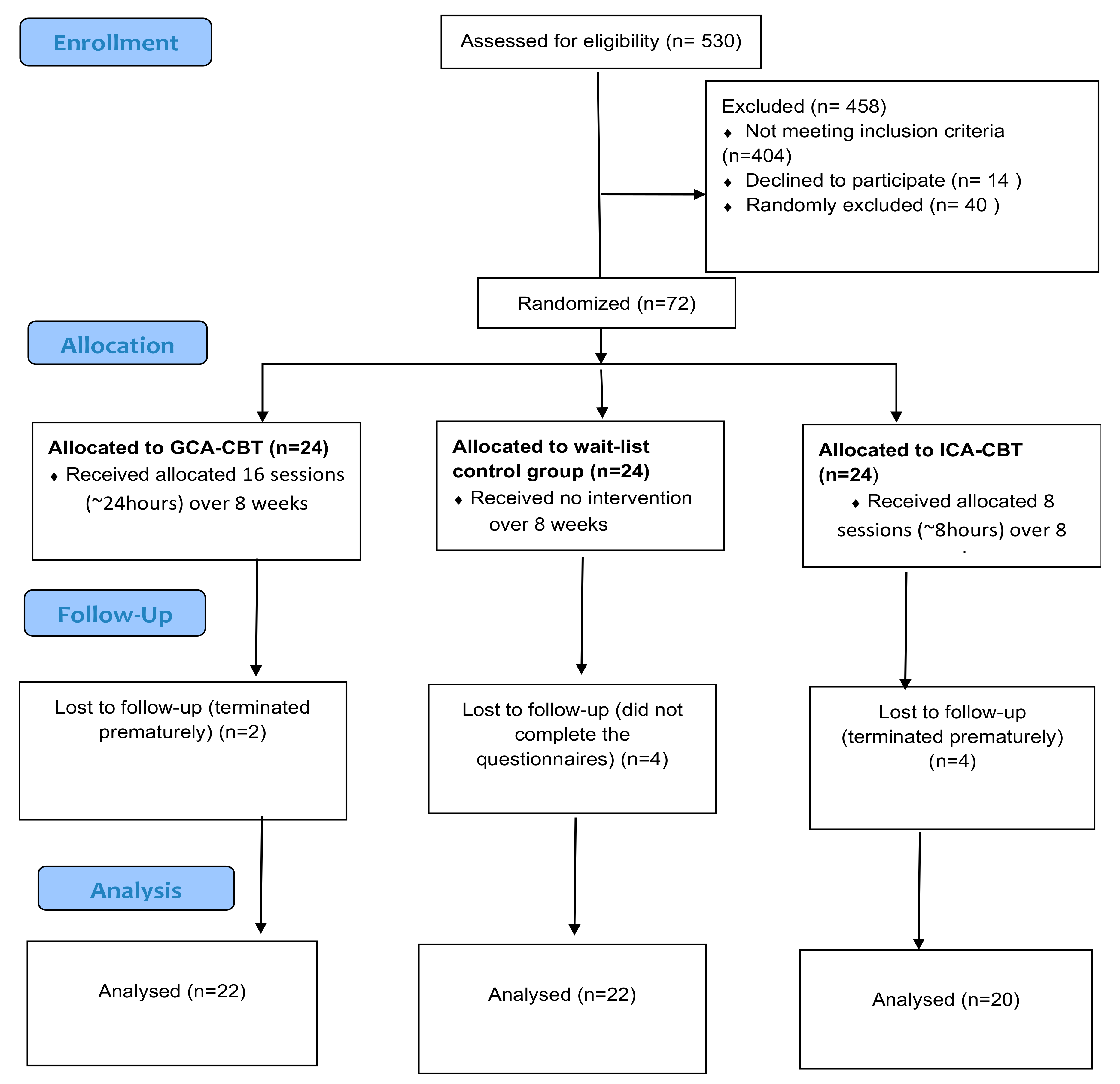

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

2.3. Participants and Setting

2.4. Instruments

2.5. Procedure

2.6. Treatment

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Result

3.1. Demographic Characteristics and Baseline Result

3.2. Reduction of Depression and Increment of Sexual Satisfaction

3.3. Sustainability of GCA-CBT and ICA-CBT Effects on Depression and Sexual Satisfaction

3.4. Complementing Qualitative Results on the Effects of ICA-CBT and GCA-CBT on Depression and Sexual Satisfaction

- “It may be that you dislike a thing while it is good for you, and it may be that you love a thing while it is evil for you, and Allah knows, while you do not know”

- “They (your wives) are your garment and you are a garment for them” [74],

- “Among His signs is that He created for you spouses of your own kind in order that you may repose to them in tranquility and He instilled in your hearts love and affection for one another; verily, in these are signs for those who reflect (on the nature of the reality)

- “Play any style and position you prefer”

4. Discussion

4.1. Strength and Limitations

4.2. Implication

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kuehner, C. Why is depression more common among women than among men? Lancet Psychiatr. 2017, 4, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Adams, L.; Savostyanova, A.; Ferssizidis, P.; McKnight, P.E.; Nezlek, J.B. Effects of social anxiety and depressive symptoms on the frequency and quality of sexual activity: A daily process approach. Behav. Res. Ther. 2011, 49, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, N.; Stephenson, C.; Yang, M.; Kumar, A.; Shao, Y.; Miller, S.; Yee, C.S.; Stefatos, A.; Gholamzadehmir, M.; Abbaspour, Z. Feasibility and Efficacy of Delivering Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Through an Online Psychotherapy Tool for Depression: Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2021, 10, e27489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Parra, V.; Rojas-Flores, A.; Rubio-Aurioles, E. Self-Reported Depression as a Predictor of Sexual Satisfaction and Sexual Function. J. Sex. Med. 2017, 14, e256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohlich, P.; Meston, C. Sexual functioning and self-reported depressive symptoms among college women. J. Sex Res. 2002, 39, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, A.H.; Harsh, V. Sexual function across aging. Curr. Psychiatr. Rep. 2016, 18, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thomas, H.N.; Thurston, R.C. A biopsychosocial approach to women’s sexual function and dysfunction at midlife: A narrative review. Maturitas 2016, 87, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muneer, A.; Minhas, F.A. Telomere biology in mood disorders: An updated, comprehensive review of the literature. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2019, 17, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mohammad, K.; Hashemi, S.M.S.; Farahani, F.K.A. Age at natural menopause in Iran. Maturitas 2004, 49, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delavar, M.; Hajiahmadi, M. Factors affecting the age in normal menopause and frequency of menopausal symptoms in Northern Iran. Iran. Red. Crescent Med. J. 2011, 13, 192. [Google Scholar]

- Abdolahi; Shaaban, K.B.; Zarghami, M. Study of Menopausal Age in Momen Living in Mazandaran Province in 2002. J. Maz. Univ. Med. Sci 2004, 14, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.M.; Ahmed, S.; Dipti, R.K.; Hawlader, M.D.H. The prevalence and associated factors of depression during pre-, peri-, and post-menopausal period among the middle-aged women of Dhaka city. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020, 54, 102312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prause, N.; Janssen, E.; Georgiadis, J.; Finn, P.; Pfaus, J. Data do not support sex as addictive. Lancet Psychiatr. 2017, 4, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lehmiller, J.J.; Garcia, J.R.; Gesselman, A.N.; Mark, K.P. Less sex, but more sexual diversity: Changes in sexual behavior during the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. Leis. Sci. 2020, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teimourpour, N.; Bidokhti, N.M.; Pourshahbaz, A.; Ehsan, H.B. Sexual desire in Iranian female university students: Role of marital satisfaction and sex guilt. Iran. J. Psychiatr. Behav. Sci. 2014, 8, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard, S.; Godbout, N.; Sabourin, S. Sexual attitudes and activities in women with borderline personality disorder involved in romantic relationships. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2009, 35, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarbo, C.; Brugnera, A.; Compare, A.; Secomandi, R.; Candeloro, I.; Malandrino, C.; Betto, E.; Trezzi, G.; Rabboni, M.; Bondi, E. Negative metacognitive beliefs predict sexual distress over and above pain in women with endometriosis. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2019, 22, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlAwlaqi, A.; Amor, H.; Hammadeh, M.E. Role of hormones in hypoactive sexual desire disorder and current treatment. J. Turk. Ger. Gynecol. Assoc. 2017, 18, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finch, A.; Metcalfe, K.; Chiang, J.; Elit, L.; McLaughlin, J.; Springate, C.; Demsky, R.; Murphy, J.; Rosen, B.; Narod, S. The impact of prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy on menopausal symptoms and sexual function in women who carry a BRCA mutation. Gynecol. Oncol. 2011, 121, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T. Cognitive Therapy of Depression; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Beach, S.R.; Katz, J.; Kim, S.; Brody, G.H. Prospective effects of marital satisfaction on depressive symptoms in established marriages: A dyadic model. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2003, 20, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yazdanpanahi, Z.; Beygi, Z.; Akbarzadeh, M.; Zare, N. To investigate the relationship between stress, anxiety and depression with sexual function and its domains in women of reproductive age. Int. J. Med Res. Health Sci. 2018, 5, 223–231. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhshi, H.; Asadpour, M.; Khodadadizadeh, A. Correlation between marital satisfaction and depression among couples in Rafsanjan. J. Qazvin. Univ. Med. Sci. 2007, 11, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Khademi, R.; Hosseini, S.H.; Nia, H.S.; Khani, S. Evaluating co-occurrence of depression and sexual dysfunction and related factors among Iranian rural women: A population-based study. BioMedicine 2020, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gheshlaghi, F.; Dorvashi, G.; Aran, F.; Shafiei, F.; Najafabadi, G.M. The study of sexual satisfaction in Iranian women applying for divorce. Int. J. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 8, 281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bahri, N.; Latifnejad Roudsari, R.; Azimi Hashemi, M. “Adopting self-sacrifice”: How Iranian women cope with the sexual problems during the menopausal transition? An exploratory qualitative study. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 38, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gracia, C.R.; Freeman, E.W. Onset of the menopause transition: The earliest signs and symptoms. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. 2018, 45, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadivala, Z.; Merghati-Khoei, E.; Underwood, C.; Mirghafourvand, M.; Allahverdipour, H. Sexual motivations during the menopausal transition among Iranian women: A qualitative inquiry. BMC Women’s Health 2018, 18, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidvar, S.; Bakouie, F.; Amiri, F.N. Sexual function among married menopausal women in Amol (Iran). J. Mid-Life Health 2011, 2, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbenick, D.; Reece, M.; Hensel, D.; Sanders, S.; Jozkowski, K.; Fortenberry, J.D. Association of lubricant use with women’s sexual pleasure, sexual satisfaction, and genital symptoms: A prospective daily diary study. J. Sex. Med. 2011, 8, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, D.; Panay, N. Treating vulvovaginal atrophy/genitourinary syndrome of menopause: How important is vaginal lubricant and moisturizer composition? Climacteric 2016, 19, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Muhamad, R.; Horey, D.; Liamputtong, P.; Low, W.Y.; Sidi, H. Meanings of sexuality: Views from Malay women with sexual dysfunction. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2019, 48, 935–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdolmanafi, A.; Nobre, P.; Winter, S.; Tilley, P.M.; Jahromi, R.G. Culture and sexuality: Cognitive–emotional determinants of sexual dissatisfaction among Iranian and New Zealand women. J. Sex. Med. 2018, 15, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Raisi, F.; Yekta, Z.P.; Ebadi, A.; Shahvari, Z. What are Iranian married women’s rewards? Using interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction: A qualitative study. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2015, 30, 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhamad Nasharudin, N.A.; Idris, M.A.; Loh, M.Y.; Tuckey, M. The role of psychological detachment in burnout and depression: A longitudinal study of Malaysian workers. Scand. J. Psychol. 2020, 61, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhamad, R.; Horey, D.; Liamputtong, P.; Low, W.Y.; Mohd Zulkifli, M.; Sidi, H. Transcripts of Unfulfillment: A Study of Sexual Dysfunction and Dissatisfaction among Malay-Muslim Women in Malaysia. Religions 2021, 12, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richters, J.; Khoei, E.M. Concepts of sexuality and health among Iranian women in Australia. Aust. Fam. Physician 2008, 37, 190. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, S.A. Islamic transcendental wellbeing model for Malaysian Muslim women: Implication on counseling. Asian Soc. Sci. 2015, 11, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beshir, E.; Beshir, M.R. Blissful Marriage: A Practical Islamic Guide; Amana Publications: Beltsville, GA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Nafzawi, M.I.M. The Perfumed Garden of Sensual Delight; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Badri, M. Abu Zayd al-Balkhi’s Sustenance of the Soul: The Cognitive Behavior Therapy of a Ninth Century Physician; International Institute of Islamic Thought (IIIT): Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Awaad, R.; Ali, S. Obsessional Disorders in al-Balkhi′ s 9th century treatise: Sustenance of the Body and Soul. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 180, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, M.Z.; Varma, S.L. Religious psychotherapy in depressive patients. Psychother. Psychosom. 1995, 63, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.A.; Shuen, P.K. An Islamic perspective on multicultural counseling: A Malaysian experience of Triad Training Model (TTM). Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 2014, 19, 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Naeem, F.; Latif, M.; Mukhtar, F.; Kim, Y.R.; Li, W.; Butt, M.G.; Kumar, N.; Ng, R. Transcultural adaptation of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) in Asia. Asia-Pac. Psychiatr. 2021, 13, e12442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, P.A.; Iwamasa, G.Y. Culturally Responsive Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy: Assessment, Practice, and Supervision; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; bt Roslan, S.; binti Ahmad, N.A.; binti Omar, Z.; Zhang, L. Effectiveness of group interpersonal psychotherapy for decreasing aggression and increasing social support among Chinese university students: A randomized controlled study. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 251, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, P.; Brière, F.N.; Stice, E. Major depression prevention effects for a cognitive-behavioral adolescent indicated prevention group intervention across four trials. Behav. Res. Ther. 2018, 100, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmani, Z.; Zargham-Boroujeni, A.; Salehi, M.; Killeen, T.K.; Merghati-Khoei, E. The existing therapeutic interventions for orgasmic disorders: Recommendations for culturally competent services, narrative review. Iran. J. Reprod. Med. 2015, 13, 403. [Google Scholar]

- Azizi, M.; Fooladi, E.; Bell, R.J.; Elyasi, F.; Masoumi, M.; Davis, S.R. Depressive symptoms and associated factors among Iranian women at midlife: A community-based, cross-sectional study. Menopause 2019, 26, 1125–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshi, Z.; Asadi Younesi, M.R.; Khamesan, A. The effect of self-esteem education with cognitive-behavioral approach on academic motivation in female students. Int. J. Sch. 2020, 2, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Barog, Z.S.; Younesi, S.J.; Sedaghati, A.H.; Sedaghati, Z. Efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on quality of life of mothers of children with cerebral palsy. Iran. J. Psychiatr. 2015, 10, 86. [Google Scholar]

- Zakaria, N.; Akhir, N.S.M. Theories and modules applied in Islamic counseling practices in Malaysia. J. Relig. Health 2017, 56, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, S.A. A Therapeutic Journey to Marital Sexual Satisfaction. Faculty of Educational Studies. Available online: http://www.puasbook.com/N_ShowDetails.aspx?qBookID=EA2527 (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- Tripolt, N.J.; Stekovic, S.; Aberer, F.; Url, J.; Pferschy, P.N.; Schröder, S.; Verheyen, N.; Schmidt, A.; Kolesnik, E.; Narath, S.H. Intermittent fasting (alternate day fasting) in healthy, non-obese adults: Protocol for a cohort trial with an embedded randomized controlled pilot trial. Adv. Ther. 2018, 35, 1265–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Plano Clark, V.L.; Schumacher, K.; West, C.; Edrington, J.; Dunn, L.B.; Harzstark, A.; Melisko, M.; Rabow, M.W.; Swift, P.S.; Miaskowski, C. Practices for embedding an interpretive qualitative approach within a randomized clinical trial. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2013, 7, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Hopewell, S.; Schulz, K.F.; Montori, V.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Devereaux, P.; Elbourne, D.; Egger, M.; Altman, D.G. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Int. J. Surg. 2012, 10, 28–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nair, B. Clinical trial designs. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2019, 10, 193. [Google Scholar]

- Zabor, E.C.; Kaizer, A.M.; Hobbs, B.P. Randomized controlled trials. Chest 2020, 158, S79–S87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashcroft, R.E. The declaration of Helsinki. In The Oxford Textbook of Clinical Research Ethics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ghassemzadeh, H.; Mojtabai, R.; Karamghadiri, N.; Ebrahimkhani, N. Psychometric properties of a Persian-language version of the Beck Depression Inventory-Second edition: BDI-II-PERSIAN. Depress. Anxiety 2005, 21, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, D.H.; Olson, A.K. PREPARE/ENRICH program: Version 2000. In Preventive Approaches in Couples Therapy; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1999; pp. 196–216. [Google Scholar]

- Fowers, B.J.; Olson, D.H. ENRICH Marital Inventory: A discriminant validity and cross-validation assessment. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 1989, 15, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arab Alidousti, A.; Nakhaee, N.; Khanjani, N. Reliability and validity of the Persian versions of the ENRICH marital satisfaction (brief version) and Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scales. Health Dev. J. 2015, 4, 158–167. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, F.L.; Hornby, J.; Sheringham, J.; Linke, S.; Ashton, C.; Moore, K.; Stevenson, F.; Murray, E. DIAMOND (DIgital Alcohol Management ON Demand): A mixed methods feasibility RCT and embedded process evaluation of a digital health intervention to reduce hazardous and harmful alcohol use. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2017, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- White, J.R.; Freeman, A.S. Cognitive-Behavioral Group Therapy: For Specific Problems and Populations; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, S.A. The Role of Islamic Family Therapy on Family Empowerment. In Proceedings of the Conference of Family Empowering and Establish Health, Semnan Province, Iran, 19 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, S.A. Rasch Model Analysis on Malay Love Song Lyrics and Its Relationship with Willingness for Counselling Help Seeking. Available online: https://www.sid.ir/En/Seminar/ViewPaper.aspx?ID=43890 (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- Hassan, S.A. Discernment Counseling for Muslim couples: A Shariah Compliance Model. In Proceedings of the 17th Annual Oxford Family Counseling Institute, Oxford University, Oxford, UK, 16–23 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdle; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.Y. The Holy Qur’an; Wordsworth Editions: Herts, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zakaria, N.; Akhir, N.S.M. Incorporating Islamic creed into Islamic counselling process: A guideline to counsellors. J. Relig. Health 2019, 58, 926–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalal, B.; Samir, S.W.; Hinton, D.E. Adaptation of CBT for traumatized Egyptians: Examples from culturally adapted CBT (CA-CBT). Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2017, 24, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, F.M.; Hassan, S.A.; Talib, M.A.; Zakaria, N.S. Perfectionism and Marital Satisfaction among Graduate Students: A Multigroup Invariance Analysis by Counseling Help-seeking Attitudes. Pol. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 48, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliam, C.M.; Cottone, R.R. Couple or individual therapy for the treatment of depression: An update of the empirical literature. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 2005, 33, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, S.M.; Donegan, E.; Frey, B.N.; Fedorkow, D.M.; Key, B.L.; Streiner, D.L.; McCabe, R.E. Cognitive behavior therapy for menopausal symptoms (CBT-Meno): A randomized controlled trial. Menopause 2019, 26, 972–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujisawa, D.; Nakagawa, A.; Tajima, M.; Sado, M.; Kikuchi, T.; Hanaoka, M.; Ono, Y. Cognitive behavioral therapy for depression among adults in Japanese clinical settings: A single-group study. BMC Res. Notes 2010, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Safakorturk, C.; Arkar, H. Effect of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Sexual Satisfaction, Marital Adjustment, and Levels of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms in Couples with Vaginismus. Turk Psikiyatr. Derg. 2017, 28, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Barzoki, M.H.; Seyedroghani, N.; Azadarmaki, T. Sexual dissatisfaction in a sample of married Iranian women. Sex. Cult. 2013, 17, 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, O.-R.; Sotude, S.O.; Khojaste-rnehr, R. Study of Impacts of Group Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (CBT) on Depression Reduction and Marital Satisfaction Increase in Married Women. Women’s Stud. Sociol. Psychol. 2010, 8, 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Peleg-Sagy, T.; Shahar, G. The prospective associations between depression and sexual satisfaction among female medical students. J. Sex. Med. 2013, 10, 1737–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyke, R.E.; Clayton, A.H. Psychological treatment trials for hypoactive sexual desire disorder: A sexual medicine critique and perspective. J. Sex. Med. 2015, 12, 2451–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conradi, H.J.; Noordhof, A.; Dingemanse, P.; Barelds, D.P.; Kamphuis, J.H. Actor and partner effects of attachment on relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction across the genders: An APIM approach. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2017, 43, 700–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, D.C.; Wong, W.C.; Ho, S.C. Are post-menopausal women “half-a-man”: Sexual beliefs, attitudes and concerns among midlife Chinese women. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2007, 34, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Session | Purpose | Agenda | Homework |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 | Psychoeducation Educate about Depression Socialize to CBT Motivate the patient | What is depression? Review symptoms of depression, Introduce the CBT approach to depression, explain cognitive and behavioral components of depression, explain the goal of therapy, eliciting goals from groups, and make a goal list. | What are the symptoms of depression? What are your symptoms? Make a problem list with personal priority |

| 3–4 | Activating the patient behavioral modification How activity affects mood. Modifying activities to improve mood. | Outline the relationship between mood and activities. Activity scheduling. Identify pleasurable and mastery activities. Specifying behavioral change to meet goals. Behavioral modification. | Keep a diary and enter activities; monitoring/rating mood and activity. What activities improve mood/worsen it? |

| 5–6 | Cognitive intervention: relation between situation, thinking, and mood; Identify negative automatic thoughts (NAT) | What are thoughts? What is self-talk? How can thought affect body, actions and mood? Introduce negative thoughts, negative automatic thoughts. NATs related to menopause and its symptoms | Three columns of DTR identify situation, thoughts and moods, identify your menopausal symptoms. |

| 7–12 | Testing NATs Identify cognitive distortion, underlie NATs | Testing NATs by group’s priorities, interpersonal conflicts, cognitive distortion; Explain dysfunctional rules and assumptions related to sexual satisfaction. Introduce Downward arrow | Complete DTR with alternatives, Cognitive distortions related to menopause and sexual satisfaction. |

| 13–15 | Problem-solving Introduce core beliefs | Problem-solving strategies. Discussion of core-beliefs based on Quran verses. | Problem-solving tasks. Identify “Rules of your mind” |

| 16 | Relapse prevention termination | Review of the therapy. Relapse prevention. Preparation for ending therapy | Applying the techniques in their lives. |

| Characteristic | Control | CA-CBT | CA-CBT | Levene |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 22 | (Group) | (Individual) | Test | |

| n = 22 | n = 20 | Sig.p | ||

| Age | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | N.A. |

| 40–45 | 6 (28%) | 7(32%) | 5(24) | |

| 46–50 | 8(36%) | 7(32%) | 7(33) | |

| 51–55 | 8(36%) | 8(36%) | 8(40) | |

| Education | N.A. | |||

| Primary school | 8(30%) | 7(32%) | 7(30%) | |

| Diploma | 12(60%) | 12(55%) | 11(60%) | |

| Bachelor | 2(10%) | 3(13%) | 2(10%) | |

| Children | N.A. | |||

| 0–2 | 6(27%) | 6(27%) | 7(30%) | |

| 3–6 | 14(64%) | 14 (64%) | 11(60%) | |

| 6> | 2(9%) | 2(9%) | 2(10%) | |

| Employment | N.A. | |||

| Housewife | 15(68%) | 15(68%) | 14(70%) | |

| Employee | 3(14%) | 3(14%) | 3 (15%) | |

| Retired | 4(18%) | 4(18%) | 3(15%) | |

| Income | N.A. | |||

| >300 | 8(36%) | 8(36%) | 7(30%) | |

| 300–599 | 9(41%) | 9(41%) | 9 (45%) | |

| 600> | 5(23%) | 5(23%) | 4 (20%) | |

| Income | M = 604,545 | M = 598,181 | M = 575,000 | p = 0.92 |

| −2.27 | −2.09 | −1.81 | ||

| Age | M = 48.63(4.63) | M = 48.90(4.56) | M = 45.40(4.22) | p = 0.84 |

| Sexual satisfaction | M = 17.86 (4.85) | M = 17.04 (4.68) | M = 19.00(4.75) | p = 0.57 |

| Depression pre-test | M = 33.95 | M = 34.09 | M = 32.30 | p = 0.96 |

| −9.6 | −8.34 | −8.73 |

| Tests of within-Subjects on Depression and Sexual Satisfaction over Time in GCA-CBT and ICA-CBT | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Sexual Satisfaction | ||||||||||

| Group | Tests | Mean | SE | ρ-Value | Mean | SE | ρ-Value | ||||

| GCA-CBT | T1 | T2 | 21.90 * | 1.19 | 0.001 * | −16.09 * | 0.98 | 0.001 * | |||

| T1 | T3 | 21.31 * | 1.35 | 0.001 * | −15.31 * | 1.06 | 0.001 * | ||||

| T2 | T3 | −0.59 | 0.45 | 0.622 | 0.77 | 0.45 | 0.304 | ||||

| ICA-CBT | T1 | T2 | 21.45 * | 0.84 | 0.001 * | −15.55 * | 1.32 | 0.001 * | |||

| T1 | T3 | 0.55 * | 1.04 | 0.001 * | −14.30 * | 1.24 | 0.001 * | ||||

| T2 | T3 | −0.90 | 0.53 | 0.331 | 1.25 | 0.69 | 0.260 | ||||

| Pairwise Comparisons of Three Times on Depression and Sexual Satisfaction in ICA-CBT and GCA-CBT | |||||||||||

| Depression | Sexual Satisfaction | ||||||||||

| Group | Tests | Mean (SD) | df | F | ρ-Value | ηp2 | Mean (SD) | df | F | ρ-Value | ηp2 |

| GCA-CBT | T1 | 33.95 (9.64) | 1.21 | 269.60 | 0.001 * | 0.92 | 17.04 (4.68) | 1.21 | 214.88 | 0.001 * | 0.91 |

| T2 | 12.04 (5.89) | 33.13 (5.56) | |||||||||

| T3 | 12.63 (6.41) | 32.36 (5.69) | |||||||||

| ICA-CBT | T1 | 32.30 (8.73) | 1.19 | 422.85 | 0.001 * | 0.95 | 19.00 (4.75) | 1.19 | 118.77 | 0.001 * | 0.86 |

| T2 | 10.85 (6.17) | 34.55 (5.76) | |||||||||

| T3 | 11.75 (6.59) | 33.30 (5.67) | |||||||||

| Tests of Between-Subjects Effects on Depression and Sexual Satisfaction at T3 among Three Groups | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Sexual Satisfaction | |||||||

| Source | Mean (SD) | F | ρ-Value | ηp2 | Mean (SD) | F | ρ-Value | ηp2 |

| GCA-CBT | 12.63 (6.41) | 73.90 | 0.001 * | 0.70 | 32.36 (5.69) | 56.57 | 0.001 * | 0.65 |

| ICA-CBT | 11.75 (6.59) | 33.30 (5.67) | ||||||

| C-CBT | 33.77 (7.17) | 17.90 (4.57) | ||||||

| Pairwise Comparisons of Three Groups on Depression and Sexual Satisfaction at T3 | ||||||||

| Group | Variables | |||||||

| Depression | Sexual Satisfaction | |||||||

| Mean | SE | ρ-Value | Mean | SE | ρ-Value | |||

| GCA-CBT | ICA-CBT | 0.88 | 2.08 | 1.00 | −0.93 | 1.64 | 1.00 | |

| C-CBT | −21.13 * | 2.03 | 0.001 * | 14.46 * | 1.60 | 0.001 * | ||

| ICA-CBT | C-CBT | −22.02 * | 2.08 | 0.001 * | 15.39 * | 1.64 | 0.001 * | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khoshbooii, R.; Hassan, S.A.; Deylami, N.; Muhamad, R.; Engku Kamarudin, E.M.; Alareqe, N.A. Effects of Group and Individual Culturally Adapted Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Depression and Sexual Satisfaction among Perimenopausal Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7711. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147711

Khoshbooii R, Hassan SA, Deylami N, Muhamad R, Engku Kamarudin EM, Alareqe NA. Effects of Group and Individual Culturally Adapted Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Depression and Sexual Satisfaction among Perimenopausal Women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(14):7711. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147711

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhoshbooii, Robab, Siti Aishah Hassan, Neda Deylami, Rosediani Muhamad, Engku Mardiah Engku Kamarudin, and Naser Abdulhafeeth Alareqe. 2021. "Effects of Group and Individual Culturally Adapted Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Depression and Sexual Satisfaction among Perimenopausal Women" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 14: 7711. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147711

APA StyleKhoshbooii, R., Hassan, S. A., Deylami, N., Muhamad, R., Engku Kamarudin, E. M., & Alareqe, N. A. (2021). Effects of Group and Individual Culturally Adapted Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Depression and Sexual Satisfaction among Perimenopausal Women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), 7711. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147711