Cardiovascular Risk Factor and Disease Measures from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

Study Design, Setting and Participants

3. Measures

3.1. Tobacco Use Status

3.2. Cardiovascular Risk Factors

3.3. Functionally Important Health Measures

“Does your health limit you in any of the following activities: Walking 3 blocks?” (responses: yes/no),

“In the past 7 days, how would you rate your fatigue on average? By fatigue, we mean feeling unrested or overly tired during the day, no matter how many hours of sleep you’ve had,” (responses: none, mild, moderate, severe, very severe), and “In general, how would you rate your physical health?” (responses: excellent, very good, good, fair, poor).

3.4. Cardiovascular Diseases

3.5. Covariates

4. Statistical Analysis

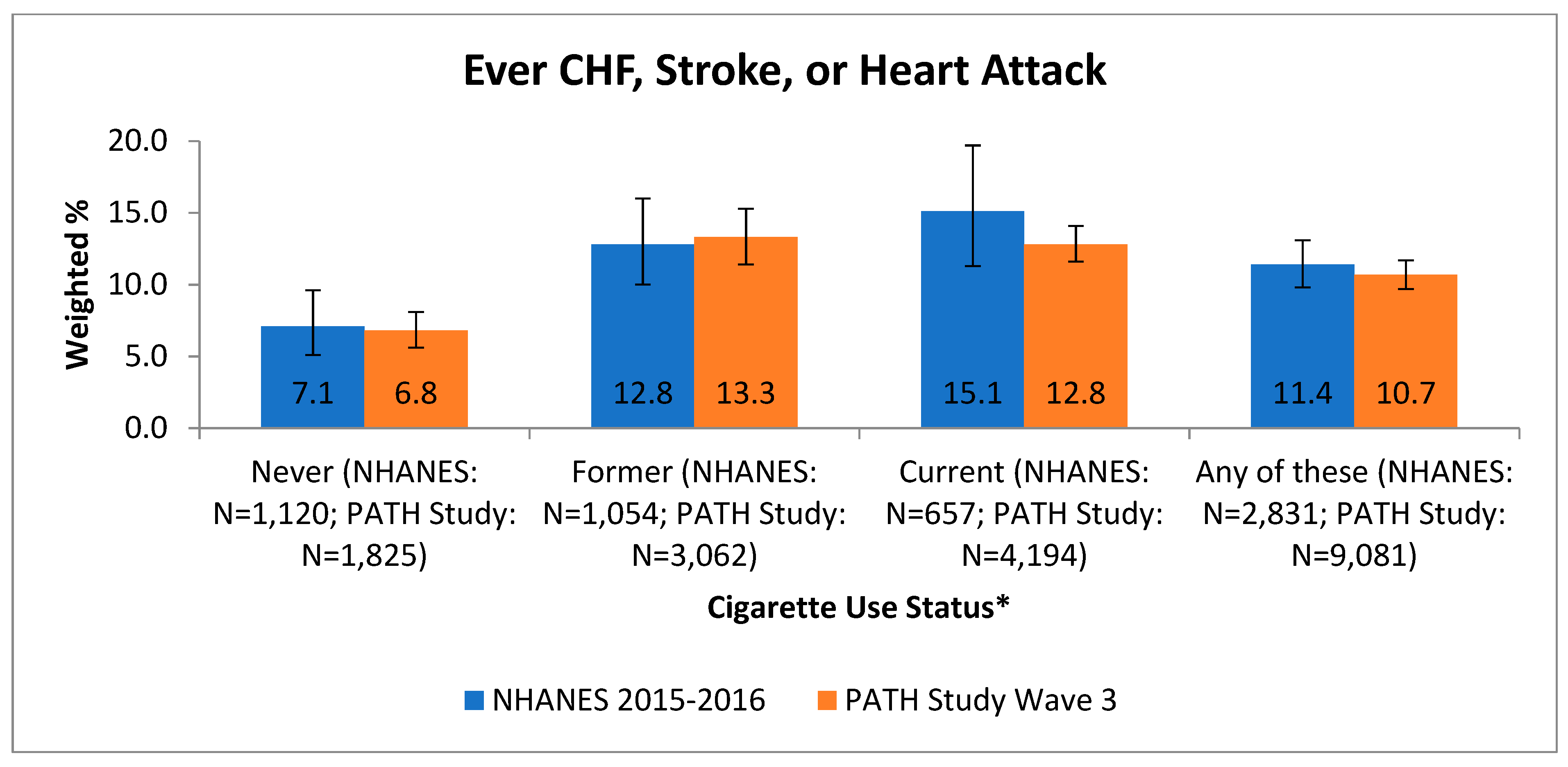

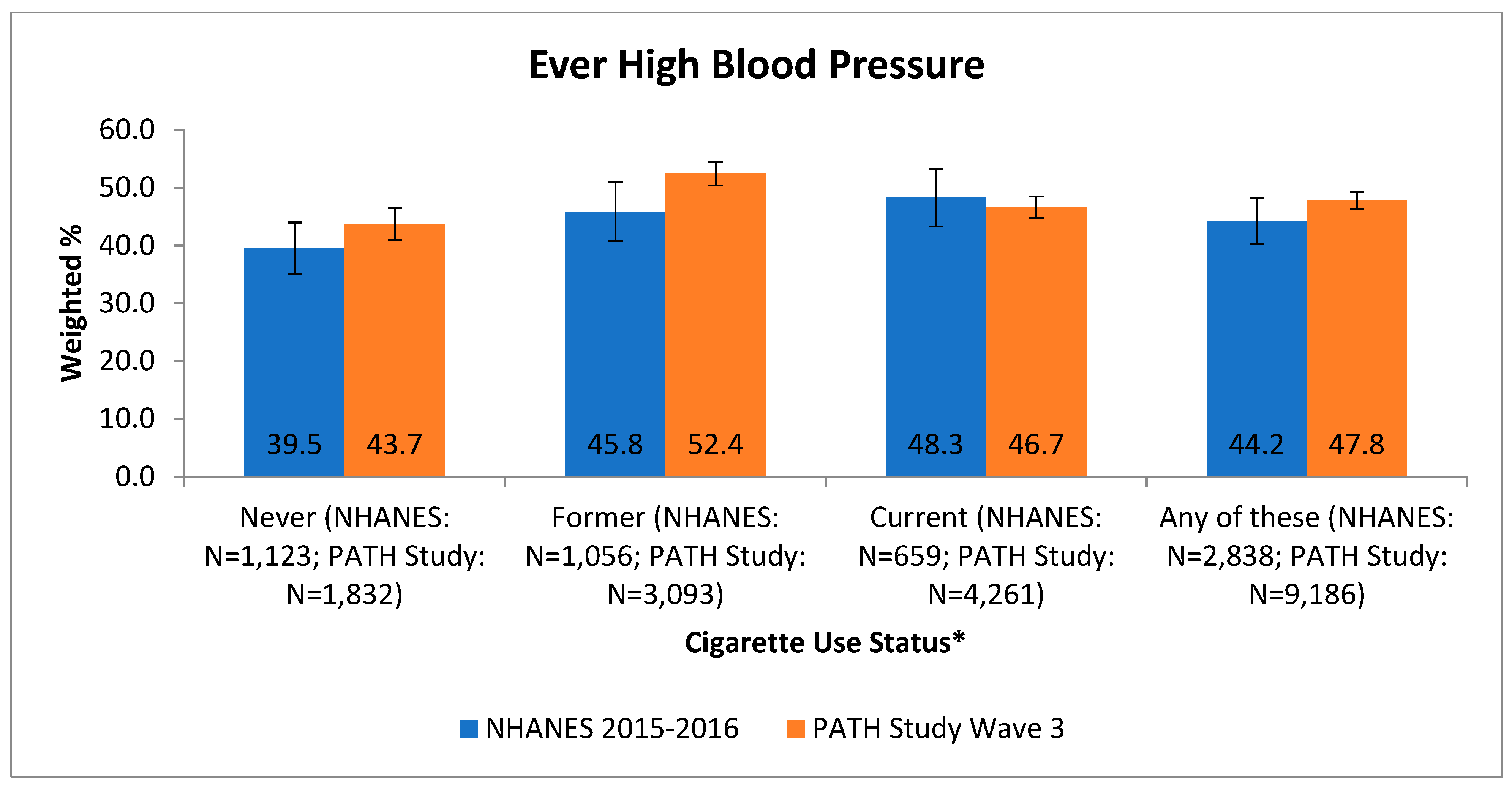

5. Results

6. Reliability and Validity

7. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Disclaimer

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Chronic Disease and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014.

- Kannel, W.; McGee, D.; Castelli, W. Latest Perspectives on Cigarette Smoking and Cardiovascular Disease: The Framingham Study. J. Card. Rehabil. 1984, 4, 267–277. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, M.A.; Oates, J.A.; Ockene, J.K.; Hennekens, C.H. Statement on smoking and cardiovascular disease for health care professionals. American Heart Association. Circulation 1992, 86, 1664–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Benjamin, E.J.; Virani, S.S.; Callaway, C.W.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Chang, A.R.; Cheng, S.; Chiuve, S.E.; Cushman, M. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2018 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018, 137, e67–e492. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, S.; Hawken, S.; Ounpuu, S.; Dans, T.; Avezum, A.; Lanas, F.; McQueen, M.; Budaj, A.; Pais, P.; Varigos, J.; et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control study. Lancet 2004, 364, 937–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, A.; Ambrose, B.K.; Conway, K.P.; Borek, N.; Lambert, E.; Carusi, C.; Taylor, K.; Crosse, S.; Fong, G.T.; Cummings, K.M. Design and methods of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Tob. Control 2017, 26, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tourangeau, R.; Yan, T.; Sun, H.; Hyland, A.; Stanton, C.A. Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) reliability and validity study: Selected reliability and validity estimates. Tob. Control 2019, 28, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharpless, N. Statement on Consumer Warning to Stop Using THC Vaping Products Amid Ongoing Investigation into Lung Illnesses. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/statement-consumer-warning-stop-using-thc-vaping-products-amid-ongoing-investigation-lung-illnesses?utm_source=Eloqua&utm_medium=email&utm_term=stratcomms&utm_content=pressrelease&utm_campaign=CTP%20News%3A%20Vaping%20Update%20-%2010419 (accessed on 7 October 2019).

- Yeager, D.S.; Krosnick, J.A. The validity of self-reported nicotine product use in the 2001-2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Med Care 2010, 48, 1128–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, C.M.; Burt, V.L.; Gillum, R.F.; Pamuk, E.R. Validity of self-reported hypertension in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III, 1988-1991. Prev. Med. 1997, 26, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evaluation of National Health Interview Survey diagnostic reporting. Vital Health Stat. Ser. 2 Data Eval. Methods Res. 1994, 120, 1–116.

- American Heart Association. Coronary Artery Disease—Coronary Heart Disease. Available online: https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/consumer-healthcare/what-is-cardiovascular-disease/coronary-artery-disease (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- PROMIS. Available online: http://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- McCarthy, P.J. Pseudoreplication Further Evaluation and Application of the Balanced Half-Sample Technique. Vital Health Stat. Ser. 2 Data Eval. Methods Res. 1969, 31, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Judkins, D.R. Fay’s method for variance estimation. J. Off. Stat. 1990, 6, 223–239. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Leading Causes of Death. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Proctor, R.N. The history of the discovery of the cigarette–lung cancer link: Evidentiary traditions, corporate denial, global toll. Tob. Control 2012, 21, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Public Health Service. Smoking and Health: Report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service; Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1964.

- Ramírez-Moreno, J.M.; Muñoz-Vega, P.; Alberca, S.B.; Peral-Pacheco, D. Health-Related Quality of Life and Fatigue after Transient Ischemic Attack and Minor Stroke. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. Off. J. Natl. Stroke Assoc. 2019, 28, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newland, P.K.; Lunsford, V.; Flach, A. The interaction of fatigue, physical activity, and health-related quality of life in adults with multiple sclerosis (MS) and cardiovascular disease (CVD). Appl. Nurs. Res. 2017, 33, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pragodpol, P.; Ryan, C. Critical review of factors predicting health-related quality of life in newly diagnosed coronary artery disease patients. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2013, 28, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, S.A.E.; Muntner, P.; Woodward, M. Sex Differences in the Prevalence of, and Trends in, Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Treatment, and Control in the United States, 2001 to 2016. Circulation 2019, 139, 1025–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, M.G.; Tong, X.; Bowman, B.A. Prevalence of Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Strokes in Younger Adults. JAMA Neurol. 2017, 74, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Wave 3 (n = 11,748) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Factors | N | % | SE | |

| Tobacco use status | Non-users | 5951 | 77.0 | 0.4 |

| Exclusive cigarette smokers | 3329 | 12.9 | 0.3 | |

| Poly-tobacco users | 1398 | 5.2 | 0.2 | |

| Other tobacco users | 1049 | 5.0 | 0.2 | |

| Selected cardiovascular | High blood pressure (b) | 5391 | 46.7 | 0.6 |

| risk factors | High cholesterol (b) | 4755 | 43.2 | 0.7 |

| Diabetes | 3052 | 26.7 | 0.7 | |

| Family history of premature heart disease | 1761 | 13.6 | 0.4 | |

| BMI >= 35 | 1718 | 14.2 | 0.4 | |

| Any of these | 8296 | 72.1 | 0.5 | |

| Number of cardiovascular | 0 | 3151 | 27.9 | 0.5 |

| risk factors | 1 | 3231 | 27.9 | 0.5 |

| 2 | 2604 | 22.8 | 0.4 | |

| 3 | 1727 | 15.4 | 0.5 | |

| 4 | 613 | 5.0 | 0.3 | |

| 5 | 121 | 0.9 | 0.1 | |

| 95% CI | ||||

| mean | lower | upper | ||

| Health risk score (0 through 5) (a) | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.5 | |

| Diagnoses | N | % | SE | |

| Congestive heart failure (CHF) (b) | 505 | 3.9 | 0.2 | |

| Stroke (b) | 557 | 4.0 | 0.3 | |

| Heart attack (b),(c) | 589 | 4.8 | 0.3 | |

| Any of these | 1221 | 9.6 | 0.4 | |

| Number of these reported | 1 | 836 | 6.7 | 0.4 |

| 2 | 271 | 2.1 | 0.2 | |

| All 3 of these | 76 | 0.5 | 0.1 | |

| Some other heart condition (b),(d) | 1480 | 12.9 | 0.4 | |

| Cardiac Condition Outcome (a) Adjusted Odds Ratio or Relative Risk Ratio (b) | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Walking 3 Blocks (c) | Model 2: Fatigue (d) | Model 3: Physical Health (e) | Model 4: Risk Factor Score (f) | ||||||||||||||||

| OR | SE | Lower | Upper | RR | SE | Lower | Upper | RR | SE | Lower | Upper | OR | SE | Lower | Upper | ||||

| No | Ref | None | Ref | Excellent | Ref | 0 | Ref | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 2.90 | 0.35 | 2.28 | 3.69 | Mild | 1.21 | 0.18 | 0.90 | 1.63 | Very good | 1.85 | 0.60 | 0.98 | 3.51 | 1 | 2.97 | 0.69 | 1.88 | 4.70 |

| Moderate | 1.89 | 0.26 | 1.44 | 2.48 | Good | 3.52 | 1.18 | 1.81 | 6.83 | 2 | 6.58 | 1.44 | 4.27 | 10.15 | |||||

| Severe | 2.73 | 0.52 | 1.87 | 3.99 | Fair | 7.12 | 2.30 | 3.75 | 13.51 | 3 | 10.66 | 2.47 | 6.74 | 16.87 | |||||

| Very Severe | 4.16 | 1.12 | 2.44 | 7.11 | Poor | 16.83 | 6.07 | 8.23 | 34.42 | 4 | 23.01 | 5.37 | 14.49 | 36.55 | |||||

| 5 | 30.51 | 10.28 | 15.64 | 59.53 | |||||||||||||||

| Yes | 2.90 | 0.35 | 2.28 | 3.69 | Mild | 1.21 | 0.18 | 0.90 | 1.63 | Very good | 1.85 | 0.60 | 0.98 | 3.51 | 1 | 2.97 | 0.69 | 1.88 | 4.70 |

| Moderate | 1.89 | 0.26 | 1.44 | 2.48 | Good | 3.52 | 1.18 | 1.81 | 6.83 | 2 | 6.58 | 1.44 | 4.27 | 10.15 | |||||

| Severe | 2.73 | 0.52 | 1.87 | 3.99 | Fair | 7.12 | 2.30 | 3.75 | 13.51 | 3 | 10.66 | 2.47 | 6.74 | 16.87 | |||||

| Very Severe | 4.16 | 1.12 | 2.44 | 7.11 | Poor | 16.83 | 6.07 | 8.23 | 34.42 | 4 | 23.01 | 5.37 | 14.49 | 36.55 | |||||

| 5 | 30.51 | 10.28 | 15.64 | 59.53 | |||||||||||||||

| Yes | 2.90 | 0.35 | 2.28 | 3.69 | Mild | 1.21 | 0.18 | 0.90 | 1.63 | Very good | 1.85 | 0.60 | 0.98 | 3.51 | 1 | 2.97 | 0.69 | 1.88 | 4.70 |

| Condition Reported Past 12 Months at Wave 2 | Condition Reported Past 12 Months at Wave 3 | Pearson Correlation Coefficient (Unweighted) | Chi Square p-Value (Weighted) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N) | Yes (%) | SE | |||||

| High Blood Pressure | Yes | 3666 | 2961 | 80.8 | 0.9 | 0.70 | 0.00 |

| No | 7323 | 795 | 10.3 | 0.4 | |||

| High Cholesterol | Yes | 2587 | 1740 | 67.4 | 1.2 | 0.56 | 0.00 |

| No | 8402 | 915 | 11.5 | 0.4 | |||

| Congestive Heart Failure | Yes | 254 | 150 | 56.0 | 4.8 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| No | 10735 | 129 | 1.1 | 0.1 | |||

| Stroke | Yes | 174 | 69 | 44.9 | 5.2 | 0.37 | 0.00 |

| No | 10815 | 124 | 1.0 | 0.1 | |||

| Heart Attack | Yes | 166 | 57 | 35.8 | 6.1 | 0.33 | 0.00 |

| No | 10823 | 113 | 1.0 | 0.1 | |||

| Some other heart condition | Yes | 604 | 280 | 49.7 | 2.6 | 0.42 | 0.00 |

| No | 10385 | 364 | 3.6 | 0.2 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mahoney, M.C.; Rivard, C.; Hammad, H.T.; Blanco, C.; Sargent, J.; Kimmel, H.L.; Wang, B.; Halenar, M.J.; Kang, J.C.; Borek, N.; et al. Cardiovascular Risk Factor and Disease Measures from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7692. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147692

Mahoney MC, Rivard C, Hammad HT, Blanco C, Sargent J, Kimmel HL, Wang B, Halenar MJ, Kang JC, Borek N, et al. Cardiovascular Risk Factor and Disease Measures from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(14):7692. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147692

Chicago/Turabian StyleMahoney, Martin C., Cheryl Rivard, Hoda T. Hammad, Carlos Blanco, James Sargent, Heather L. Kimmel, Baoguang Wang, Michael J. Halenar, Jueichuan Connie Kang, Nicolette Borek, and et al. 2021. "Cardiovascular Risk Factor and Disease Measures from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 14: 7692. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147692

APA StyleMahoney, M. C., Rivard, C., Hammad, H. T., Blanco, C., Sargent, J., Kimmel, H. L., Wang, B., Halenar, M. J., Kang, J. C., Borek, N., Cummings, K. M., Lauten, K., Goniewicz, M. L., Hatsukami, D., Sharma, E., Taylor, K., & Hyland, A. (2021). Cardiovascular Risk Factor and Disease Measures from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), 7692. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147692