Psychoeducation Improved Illness Perception and Expressed Emotion of Family Caregivers of Patients with Schizophrenia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Data Collection Instruments

2.4. Family Members’ FMSS Assessments

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Family Members’ Characteristics

3.3. IPQS-R

3.4. Family Members’ FMSS Expressed Emotion Ratings

3.5. Medication Adherence Scale

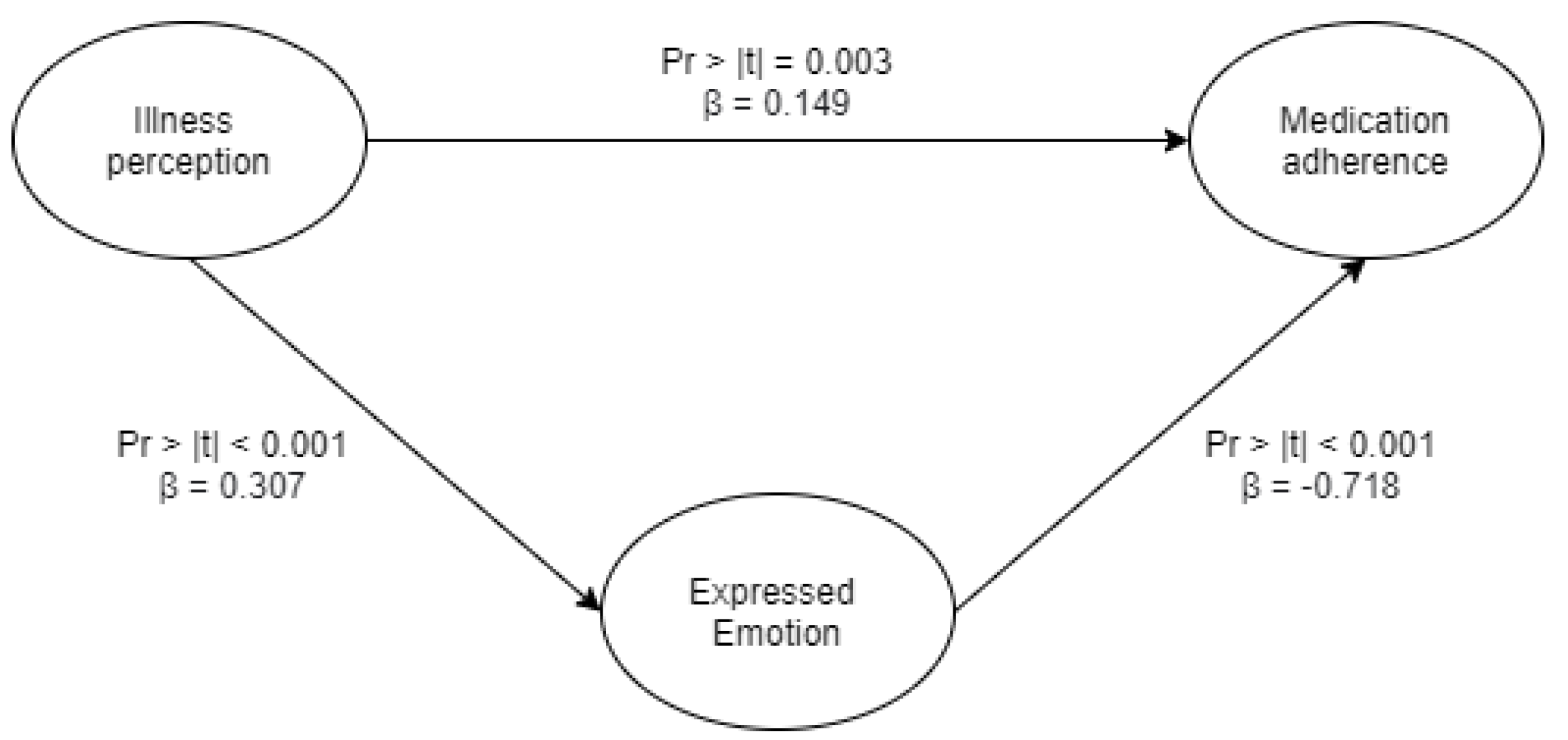

3.6. Overall Relationship between Illness Perception, Expressed Emotion, and Medication Adherence

4. Discussion

4.1. Family Members/Caregivers’ Illness Perception

4.2. Expressed Emotion

4.3. Medication Adherence

4.4. Psychoeducation in Indonesia

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lobban, F.; Barrowclough, C.; Jones, S. Assessing cognitive representations of mental health problems. II. The illness perception questionnaire for schizophrenia: Relatives’ version. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 44, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magana, A.B.; Goldstein, J.M.; Karno, M.; Miklowitz, D.J.; Jenkins, J.; Falloon, I.R. A brief method for assessing expressed emotion in relatives of psychiatric patients. Psychiatry Res. 1986, 17, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Patel, I.; Chang, J. Review of the four item Morisky medication adherence scale (MMAS-4) and eight item Morisky medication adherence scale (MMAS-8). Innov. Pharm. 2014, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompson, M.C.; Goldstein, M.J.; Lebell, M.B.; Mintz, L.I.; Marder, S.R.; Mintz, J. Schizophrenic patients’ perceptions of their relatives’ attitudes. Psychiatry Res. 1995, 57, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompson, M.C.; Pierre, C.B.; Boger, K.D.; McKowen, J.W.; Chan, P.T.; Freed, R.D. Maternal depression, maternal expressed emotion, and youth psychopathology. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2010, 38, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vika, V.; Siagian, M.; Wangge, G. Validity and reliability of Morisky Medication Adherence Scale 8 Bahasa version to measure statin adherence among military pilots. Health Sci. J. Indones. 2016, 7, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leff, J.; Kuipers, L.; Berkowitz, R.; Eberlein-Vries, R.; Sturgeon, D. A controlled trial of social intervention in the families of schizophrenic patients. Br. J. Psychiatry 1982, 141, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueser, K.T.; Corrigan, P.W.; Hilton, D.W.; Tanzman, B.; Schaub, A.; Gingerich, S.; Essock, S.M.; Tarrier, N.; Morey, B.; Vogel-Scibilia, S.; et al. Illness management and recovery: A review of the research. Psychiatr. Serv. 2002, 53, 1272–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malla, A.K.; Razarian, S.S.; Barnes, S.; Cole, J.D. Validation of the Five Minute Speech Sample in Measuring Expressed Emotion; SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Duman, Z.C.; Kuşcu, M.K.; Özgün, S. Comparison between Camberwell Family Interview and Expressed Emotion Scale in Determining Emotions of Caregivers of Schizophrenic Patients. Nöro Psikiyatr. Arşivi 2013, 50, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Tetzlaff, A.; Hilbert, A. Perceived Expressed Emotion in Adolescents with Binge-Eating Disorder. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2015, 43, 1369–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Allan, E.; Le Grange, D.; Sawyer, S.M.; McLean, L.A.; Hughes, E.K. Parental Expressed Emotion During Two Forms of Family-Based Treatment for Adolescent Anorexia Nervosa. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2018, 26, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streiner, D.L. Starting at the beginning: An introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. J. Personal. Assess. 2003, 80, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minas, H.; Diatri, H. Pasung: Physical restraint and confinement of the mentally ill in the community. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2008, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gomez-de-Regil, L.; Kwapil, T.R.; Barrantes-Vidal, N. Predictors of expressed emotion, burden and quality of life in relatives of Mexican patients with psychosis. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 21, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsherif, Z.A.; Behilak, S.; Abdelraof, A.S.E. The Relationship of Relatives’ Illness Perception, Expressed Emotion and Their Burden in Caring for Patients with Schizophrenia. Am. J. Nurs. Res. 2020, 8, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeber, J.E.; Copeland, L.A.; Good, C.B.; Fine, M.J.; Bauer, M.S.; Kilbourne, A.M. Therapeutic alliance perceptions and medication adherence in patients with bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2008, 107, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrowclough, C.; Johnston, M.; Tarrier, N. Attributions, expressed emotion, and patient relapse: An attributional model of relatives’ response to schizophrenic illness. Behav. Ther. 1994, 25, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellwood, W.; Tarrier, N.; Quinn, J.; Barrowclough, C. The family and compliance in schizophrenia: The influence of clinical variables, relatives’ knowledge and expressed emotion. Psychol. Med. 2003, 33, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, W.T. Effectiveness of psychoeducation and mutual support group program for family caregivers of chinese people with schizophrenia. Open Nurs. J. 2008, 2, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, W.T.; Chan, S.W.; Thompson, D.R. Effects of a mutual support group for families of Chinese people with schizophrenia: 18-month follow-up. Br. J. Psychiatry 2006, 189, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maramis, A.; Van Tuan, N.; Minas, H. Mental health in southeast Asia. Lancet 2011, 377, 700–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakuma, R.; Minas, H.; van Ginneken, N.; Dal Poz, M.R.; Desiraju, K.; Morris, J.E.; Saxena, S.; Scheffler, R.M. Human resources for mental health care: Current situation and strategies for action. Lancet 2011, 378, 1654–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilling, S.; Bebbington, P.; Kuipers, E.; Garety, P.; Geddes, J.; Orbach, G.; Morgan, C. Psychological treatments in schizophrenia: I. Meta-analysis of family intervention and cognitive behaviour therapy. Psychol. Med. 2002, 32, 763–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| IPQS-R Subscales | Control | Intervention | Significance of Effect b | Effect Size (Control; Intervention) c | Mean Inter-Item Correlation | Cronbach Alpha | KMO | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | ||||||

| Identity a | 9.04 (1.93) | 9 (1.71) | 8.97 (1.86) | 7.1 (2.5) | F(1,62) = 5.85 * | d = 0.02; 0.85 | - | - | - |

| Cause Items | 2.91 (0.28) | 3 (0.24) | 2.99 (0.31) | 1.5 (0.16) | F(1,62) = 696.18 *** | d = 0.35; 6.04 | 0.25 | 0.88 | 0.76 |

| Timeline Acute | 2.67 (0.88) | 2.7 (0.9) | 3.75 (1.09) | 2.87 (1.08) | F(1,62) = 9.8 *** | d = 0.03; 0.81 | 0.45 | 0.93 | 0.64 |

| Timeline Cyclical | 4.11 (0.73) | 4.13 (0.68) | 4.24 (0.58) | 4.07 (0.62) | F(1,62) = 4.65 * | d = 0.03; 0.28 | 0.7 | 0.83 | 0.56 |

| Consequence—Patient | 3.88 (0.5) | 3.98 (0.48) | 3.9 (0.48) | 3.74 (0.43) | F(1,62) = 7.07 ** | d = 0.2; 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.57 | 0.66 |

| Consequence—Relatives | 3.58 (0.32) | 3.56 (0.3) | 3.51 (0.39) | 1.76 (0.2) | F(1,62) = 216.17 *** | d = 0.06; 5.65 | 0.33 | 0.91 | 0.73 |

| Personal Control—Patient | 1.7 (0.43) | 1.72 (0.47) | 1.9 (0.43) | 3.28 (0.56) | F(1,62) = 76.45 *** | d = 0.04; 2.76 | 0.38 | 0.9 | 0.55 |

| Personal Control—Relatives | 1.77 (0.52) | 1.53 (0.42) | 1.75 (0.55) | 2.56 (0.85) | F(1,62) = 25.86 *** | d = 0.51; 1.13 | 0.36 | 0.82 | 0.6 |

| Personal Blame—Patient | 3.88 (0.6) | 3.79 (0.69) | 3.94 (0.89) | 2.37 (0.54) | F(1,62) = 25.4 *** | d = 0.14; 2.13 | 0.31 | 0.86 | 0.64 |

| Personal Blame—Relatives | 2.02 (0.35) | 2.1 (0.35) | 2.02 (0.3) | 3.03 (0.45) | F(1,62) = 72.17 *** | d = 0.23; 2.64 | 0.36 | 0.82 | 0.62 |

| Treatment Control | 2.43 (0.43) | 2.61 (0.34) | 2.53 (0.45) | 3.53 (0.68) | F(1,62) = 20.46 *** | d = 0.46; 1.73 | 0.25 | 0.85 | 0.54 |

| Illness Coherence | 3.82 (0.46) | 3.81 (0.53) | 2.69 (0.31) | 3.84 (0.45) | F(1,62) = 51.1 *** | d = 0.02; 2.98 | 0.39 | 0.91 | 0.72 |

| Emotional Representation | 3.64 (0.28) | 3.69 (0.29) | 3.71 (0.29) | 1.86 (0.15) | F(1,62) = 411.96 *** | d = 0.18; 8.01 | 0.37 | 0.96 | 0.59 |

| Family Members’ FMSS Expressed Emotion | Control | Intervention | Odds Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | ||

| Criticism | 14 | 15 | 20 | 7 | 0.32 (CI: 0.11–1.01) |

| Emotional overinvolvement | 19 | 17 | 12 | 5 | 0.46 (CI: 0.14–1.6) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Budiono, W.; Kantono, K.; Kristianto, F.C.; Avanti, C.; Herawati, F. Psychoeducation Improved Illness Perception and Expressed Emotion of Family Caregivers of Patients with Schizophrenia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7522. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147522

Budiono W, Kantono K, Kristianto FC, Avanti C, Herawati F. Psychoeducation Improved Illness Perception and Expressed Emotion of Family Caregivers of Patients with Schizophrenia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(14):7522. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147522

Chicago/Turabian StyleBudiono, Watari, Kevin Kantono, Franciscus Cahyo Kristianto, Christina Avanti, and Fauna Herawati. 2021. "Psychoeducation Improved Illness Perception and Expressed Emotion of Family Caregivers of Patients with Schizophrenia" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 14: 7522. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147522

APA StyleBudiono, W., Kantono, K., Kristianto, F. C., Avanti, C., & Herawati, F. (2021). Psychoeducation Improved Illness Perception and Expressed Emotion of Family Caregivers of Patients with Schizophrenia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), 7522. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147522