1. Introduction

Currently, in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, social interest has been stoked and research on vaccines has increased. The debate has transcended the context of the experts and flooded the public space, and has been amplified by activism on social media. All this has revealed some contradictions of the experts, confusion of the population, and, in many cases, a decrease in the credibility of vaccines that are affected by a crisis of confidence. It is also being considered whether, in certain cases, they should be mandatory, as well as the administrative and judicial procedure for imposing compulsory vaccination, and the cases in which the courts and tribunals may require it.

It should be specified that this study is based on the fact that health, as indicated in 1946 by the World Health Organization [

1], is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, and not only as an absence of disease. In this sense, education has a very close relationship with the enjoyment of optimal levels of health. For this reason, internationally renowned organizations, such as the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the Council of Europe, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and the European Commission, indicate that schools need to incorporate health education into their curricula, as a basic tool to develop healthy lifestyle habits, not only to increase the quality of life of schoolchildren, but also to work on building a better, more ecological, tolerant, and supportive world [

2]. It should also be stressed that, in the European Union (EU), infectious diseases are a priority issue within public health and, especially, vaccination, which is one of the most effective prevention measures for improving health.

Reasonably, it is essential to analyze the advantages and effectiveness of vaccines, concerns about their safety, and how they are perceived in the educational community. As Matesanz points out [

3], having an effective vaccine is not an individual solution, but rather that the maximum number of people in the environment receive it to achieve the desired “herd immunity”, and the virus then stops circulating.

It is clear that vaccines save millions of lives every year, and are one of the safest and most effective public health interventions, providing benefits on disease control and prevention, as well as social and economic benefits. Indeed, since the creation of the Expanded Program on Immunization by the WHO in 1974, the benefits have been expanding, and proof of this is the explicit recognition of the importance of vaccination and its great impact on social good, developing a Global Vaccine Action Plan (GVAP) for 2011–2020 [

4], which was approved by 194 countries in the World Health Assembly.

Vaccines are antigenic preparations consisting of microorganisms or by them, which are modified, so that they lose or attenuate their pathogenic capacity, and their purpose is to stimulate the defense mechanisms of the individual against infectious agents. The advances in molecular biology, specifically in the development of recombinant DNA technology and bioinformatics, have been essential tools for the evolution of vaccines. Likewise, the advances in the knowledge of immunity and in biological therapies cannot be forgotten [

5]. It is in the twentieth century when the activity gained a greater boom, with the incorporation of biotechnological technical processes. Indeed, from the 1990s to the present, there has been one of the most productive periods in vaccinology, with the achievement of relevant vaccines, such as against avian influenza, retrovirus diarrhea, and hepatitis A and cervical cancer caused by human papillomavirus (HPV).

At present, we live immersed in a situation of continuous virological risk. We are immersed in the pandemic caused by COVID-19, with new infectious challenges and high mortality rates, exacerbating with more virulence diseases, such as malaria, acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), tuberculosis, etc. This new global framework has brought together and strengthened the role of international bodies. In fact, as it is a public health issue that affects everyone, from the United Nations (UN) and the WHO, strategies and initiatives are being introduced to combat COVID-19, and, at the same time, to be able to continue the work of education, information, monitoring, prevention, and medication worldwide [

6].

It must be recognized that, although there is no 100% effective vaccine, nor are all vaccines equally effective, the advantages of vaccines focus on their proven effectiveness, which manifests itself in their behavior in practice and depends, in particular, on the immune capacity of the recipient, the type of vaccine, established schedules, and its availability, tolerance and stability. In the interest of public health, the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (AEMPS) may subject each batch to prior authorization and make the placing on the market conditional on its conformity. Consequently, vaccines are administered in order to stimulate the specific defense mechanisms of the individual against certain infectious agents [

7].

The European Union (EU) carries out public health policies in the member states; however, there is no common prevention model. This situation generates inequality in the access to immunization among community citizens, which has been evidenced by the pandemic caused by COVID-19. Each country designs its vaccination strategy, with regard to its epidemiological situation; however, WHO, EU and UNICEF develop prevention and immunization strategies and plans at the global and European level [

8].

It is important to emphasize that the WHO designs long-term immunization strategies and carries out specific advocacy work with a global impact, such as World Immunization Week or the European Vaccine Action Plan 2015–2020.

The EU also has a global health strategy involving the AEMPS, the Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety (DG SANTE), and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Thus, the third European action program on health 2014–2020 and the ‘joint actions’ stimulate the collaboration of the member states to solve public health problems at the European level, focusing on the following objectives: to contribute to innovative, effective and sustainable health systems; improve the citizens’ access to better and safer health care; promote health and disease prevention; and protect citizens from cross-border health threats [

9].

Our research aims to design and validate a questionnaire to study the importance of vaccines in the health of the child population, to know the influence of vaccines, analyze their development, assess their situation in the twenty-first century, and examine the need for the mandatory nature of certain vaccines.

Reasonably, it was proven that there is no questionnaire that is adequate to what is intended to be measured in our research, so it was essential to create a new questionnaire, VACUNASEDUCA [

2], following the steps we recommend for the process of the creation and validation of questionnaires by various authors [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

2. Materials and Methods

The analytical descriptive design adopted by the questionnaire validation process has been developed in several phases in which quantitative strategies and the application of different statistical techniques have predominated through the IBM SPSS26 program, for the calculation of descriptive statistics, reliability indices through Cronbach’s alpha model and the exploratory study of the factorial structure through the factor analysis of principal components. The results of these analyses have been the subject of quantitative assessments by 15 experts (

Table 1) using an ad hoc questionnaire. To evaluate the content validity, the Lawshe content index was calculated for each item using a Likert scale with a score of 1 to 3 and to evaluate the degree of agreement among experts, the Fleiss’ kappa concordance coefficient was calculated using a Likert scale with a score between 1 to 5 with respect to 3 criteria (clarity, relevance, and significance).

2.1. Participants

The sample of this research, given the subject matter studied, has been worldwide. It has been considered as the subset of individuals who agree to undergo an investigation, where it is taken as a reference to meet several criteria of representativeness of the total population. The selection has been in the interest of the researchers. Indeed, the sample consists of 1000 participants from the following 76 countries: Albania, Germany, Andorra, Angola, Saudi Arabia, Algeria, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Bangladesh, Belgium, Bolivia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Spain, Botswana, Brazil, Bulgaria, Cape Verde, Cameroon, Canada, Chile, China, Cyprus, Colombia, Ivory Coast, Cuba, Denmark, Ecuador, United Arab Emirates, Spain, United States, Estonia, Philippines, Finlandia, France, Gabon, Gambia, Georgia, Greece, Guatemala, Equatorial Guinea, Haiti, Honduras, India, Ireland, Iceland, Israel, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Jordan, Latvia, Lebanon, Liberia, Luxembourg, Morocco, Mauritius, Mauritania, Mexico, Montenegro, Mozambique, Paraguay, Peru, Poland, Portugal, United Kingdom, Russia, South Africa, Sweden, Switzerland, Thailand, Tanzania, Turkey, Ukraine, Uganda, Venezuela, Zimbabwe.

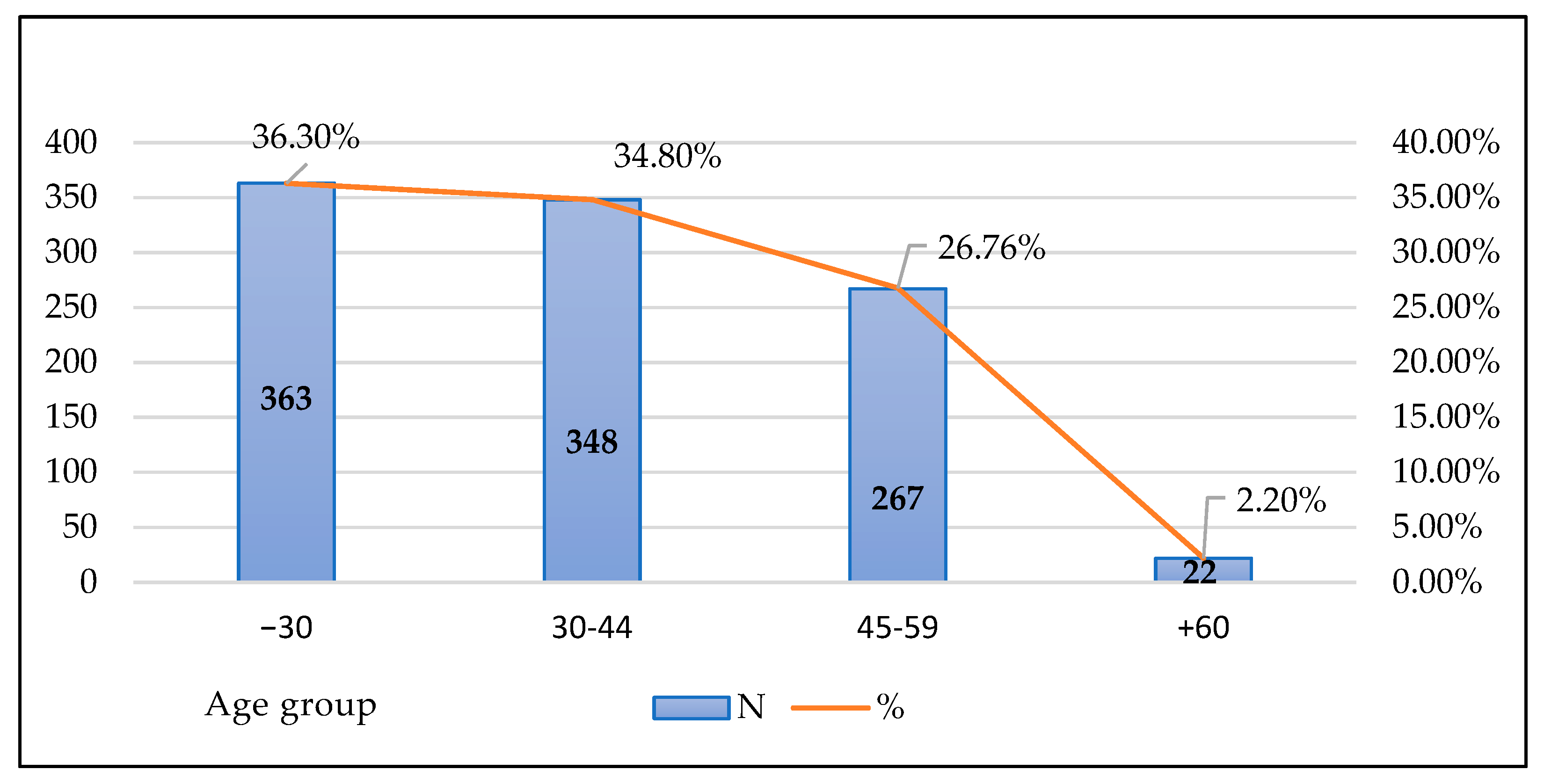

Regarding the characteristics of the sample, in relation to gender, it is made up of 694 women (69.4%) and 306 men (30.6%). The age of the sample members is mostly between 18 and 44 years (

Figure 1).

As for the work performance of the sample members, 55.4% (n = 554) belong to the health sector, 32.9% (n = 329) to the educational field and 11.7% (n = 117) to the economy sector.

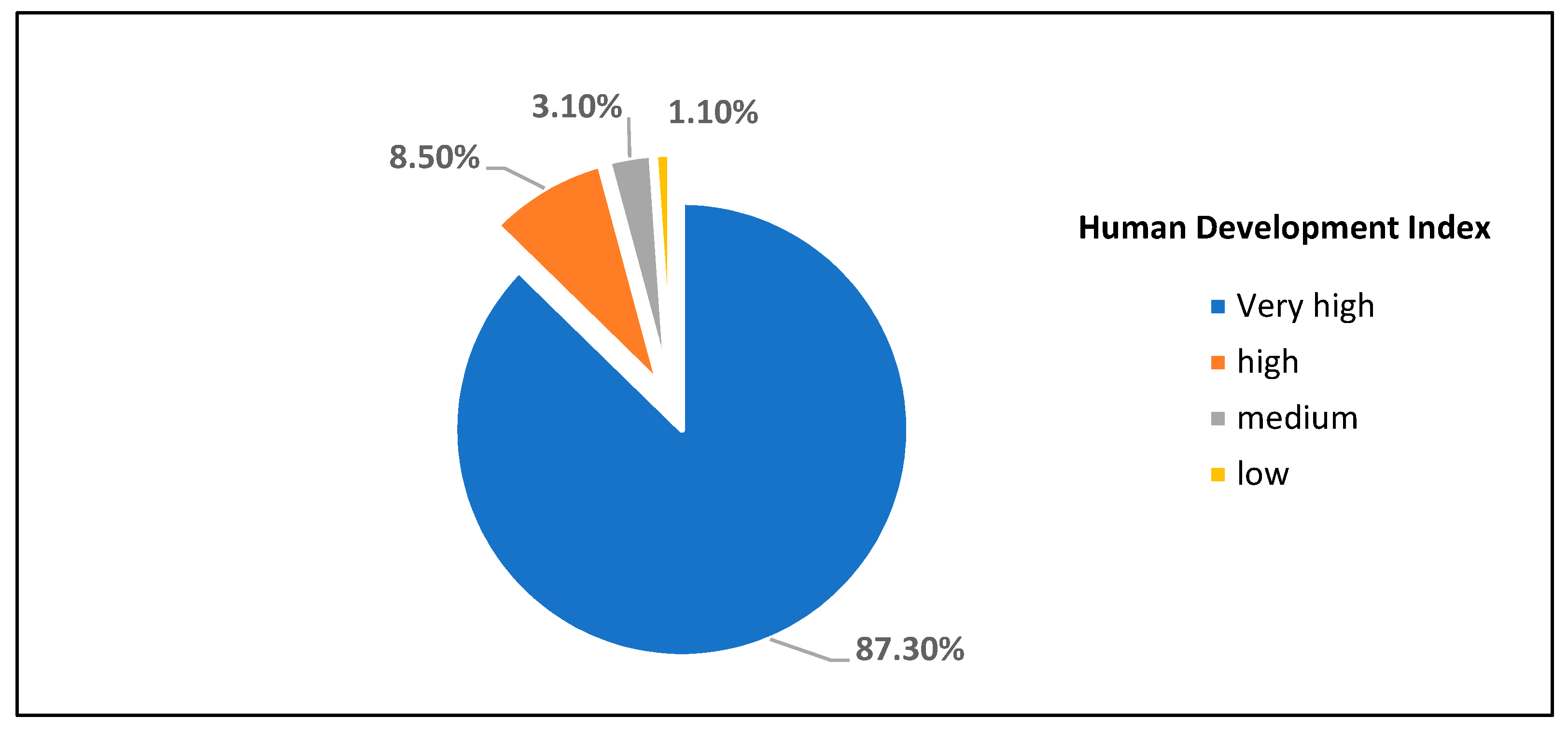

The socioeconomic level of the sample members has been established based on the country of origin through the human development index (HDI) (

Figure 2).

2.2. Instrument

As indicated, the conceptual framework of the VACUNASEDUCA questionnaire focuses on vaccines, being configured in the main variable of research, its structure is reflected in

Table 2. Each item was evaluated using a Likert scale with a rating between 1 and 3: No (1), Maybe (2), Yes (3).

2.3. Procedure

The research has been developed in the following phases: (a) delimitation of the construct to be measured and analysis of the state of the matter; (b) pilot design of the questionnaire, taking into account the objective, population, sample and format; (c) expert judgement who will assess the validity of the content of the questionnaire and make the relevant proposals for improvement and its incorporation; (d) statistical analysis of the data; (e) final proposal for the questionnaire. The study was carried out in 2019 and 2020, guaranteeing at all times the confidentiality and anonymity of the data obtained (

Supplementary File).

4. Conclusions

In health education, it is evident that the use of reliable and validated questionnaires is a very common methodological instrument that requires adequate elaboration, as it is a fundamental part of the research design and conditions the results obtained [

14,

21,

27]. Reasonably, this article has shown the process followed for the validation of the questionnaire VACUNASEDUCA, which was developed with the purpose of deepening the importance of vaccines.

It should be noted that the work began before the pandemic caused by COVID-19, being topical and highly applicable to the new challenges in vaccination in the educational context, especially in the first levels of schooling. There is no doubt that, today, one of the most worrying challenges is global health security. In addition, it is becoming clear with COVID-19 that disease outbreaks can develop faster and travel farther than ever before. Emerging threats are not limited to a single place or country, so investing in health security must be a global priority.

It should also be noted that we live in a healthier, safer, and more prosperous world than 20 years ago; however, the progress made is fragile. Indeed, more than one and a half million people die each year from vaccine-preventable diseases, and fifteen million children are still missing out on the benefits of vaccination in the least developed countries. Along these lines, the Vaccine Alliance (GAVI) has planned that, in the strategic period 2021–2025, the launch of the most complete package of vaccines in the history of the Alliance will take place, expanding the portfolio of vaccines. Logically, the introduction of new vaccines, including boosters against tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap); the birth dose of hepatitis B; multivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccines; routine oral cholera vaccine; and vaccines against respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and rabies will help protect people throughout their lives, not just during childhood [

2].

There is no doubt that global health security and the fight against COVID-19 depend on the early implementation of health systems around the world. Likewise, actions, treatments, and efforts are needed to combat this pandemic, where health education from the earliest age is of vital importance.

It must be recognized that, in order to motivate the realization of work on the subject at hand, and to be able to develop solid and effective research, it is essential to have valid tools that make it possible for the results obtained in the research to be useful to intervene in the effective improvement of the situation studied. There is no doubt that knowing what their political, social and human factors are allows us to investigate in a little-known field, promoting the study of the concerns and opinions of the human factors involved in a more direct way, such as teachers at university and non-university centers, scientists, parents and mothers, teachers in training, students, political representatives, and managers. Consequently, the researchers prioritized designing a questionnaire that was very easy to complete, in order to optimize the response of potential participants.

The VACUNASEDUCA questionnaire can be a very valuable tool in today’s society, and, as has been shown, it is easy to apply and requires few prerequisites. It is justified that it is very valid to know, in a given context, the awareness of society regarding vaccines, the assessment of their mandatory nature, the regulation by the administrations, the initial training and awareness of teachers, gender influence, information and involvement of parents, need for a vaccination register/card, and the consequences and risks of non-vaccination. It is a questionnaire of great interest not only in the educational and health fields, but it also affects the whole of society, because vaccines are an important measure, due to their high effectiveness and tolerance profile, making it possible to save millions of lives and eradicate some diseases. There is no doubt that vaccines are an investment not only because they improve the quality of life, but they also constitute an economic and social value of great importance.

It offers an original and innovative proposal that, based on the training offered to teachers on health prevention, plans to design a training plan for prevention and education for health, and reflect on the influence of the vaccination of students on the occupational health of teachers. In addition, from a gender perspective, it is possible to analyze how the effects of the inappropriate application of vaccines could affect male teachers, differently from female teachers.

It should be noted that one of the strengths of the VACUNASEDUCA questionnaire has been the very large sample used, which covers 76 countries. It is also important to note that the process of validating a questionnaire has limitations linked to the choice of the number of experts, since their number varies substantially according to the authors consulted, without establishing a specific consensus [

28]. Thus, there are authors who indicate 3 as a valid number of experts, while others establish a range between 14 and 25 experts [

29]. As indicated, 15 experts participated in the validation of the VACUNASEDUCA questionnaire, which is a number within the ranges established by different authors. Also, a significant strength of the study is the methodological rigor practiced both in the content validation process and in the internal validation process. Therefore, it can be concluded that a questionnaire is available with sufficient internal validity and reliability, and is easy to apply in different contexts and areas of society at the international level.