Living with Long Term Conditions from the Perspective of Family Caregivers. A Scoping Review and Narrative Synthesis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

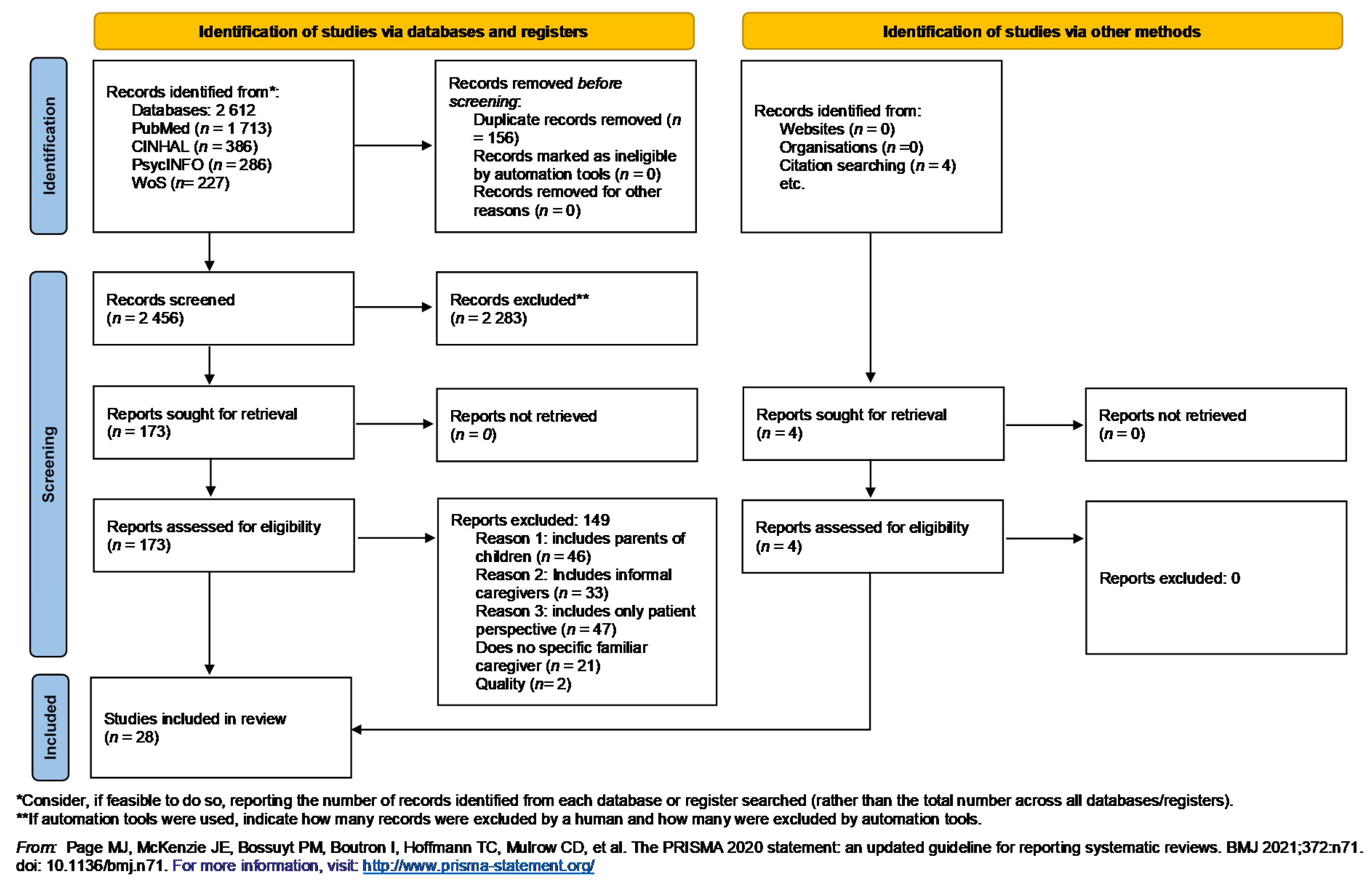

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identify the Research Question and Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- POPULATION: Family with an adult relative with LTCs.

- CONCEPT: Living with LTCs from family perspective.

- CONTEXT: Quantitative, qualitative, mix methods studies, political documents that totally or partially address the meaning and the experience of living with LTCs from the family caregiver perspective.

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Analyses

3. Results

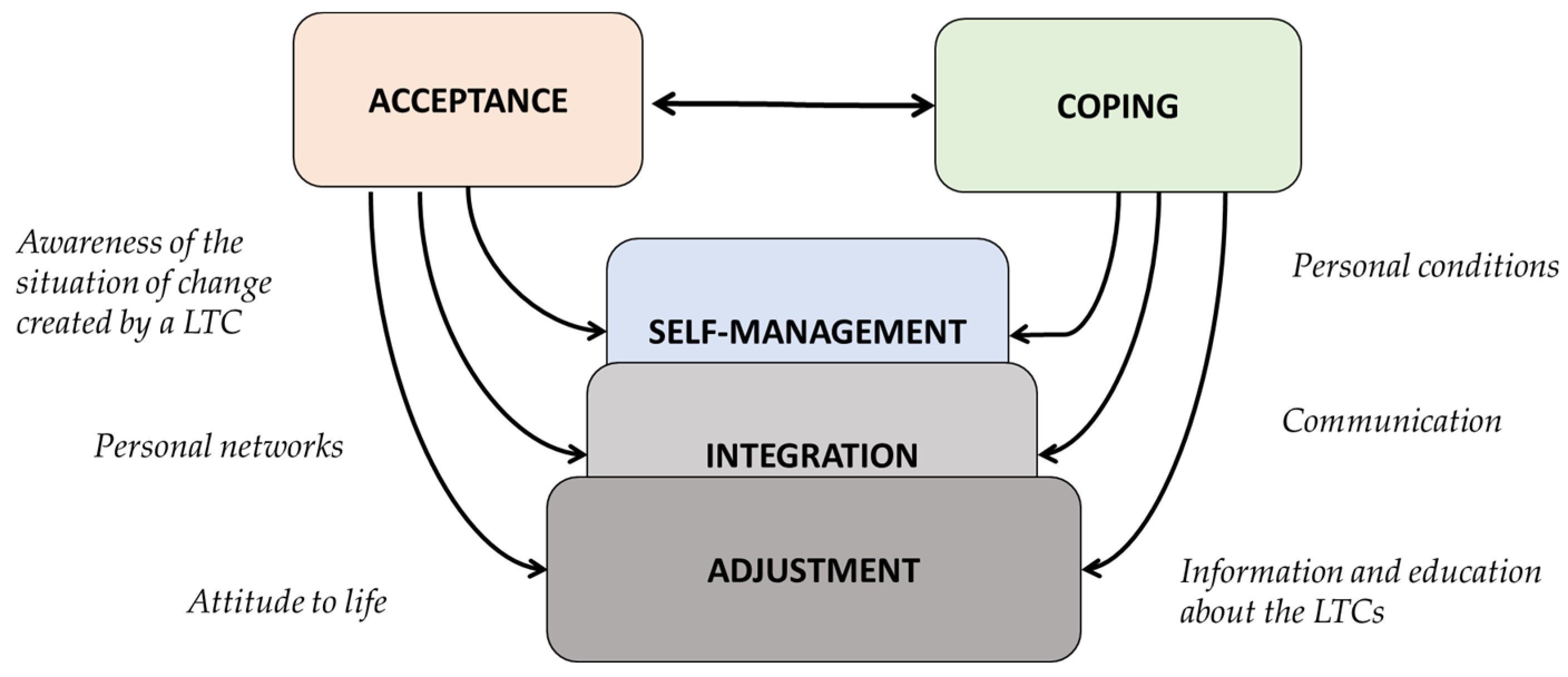

3.1. Attributes of Living with LTCs from a Family Perspective:

3.2. Mechanisms of Living with LTCs from the Family Perspective

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

7. Relevance for Clinical Practice

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social Informe de Evaluación Estratégica de la Cronicidad. Estrategia para el Abordaje de la Cronicidad en el Sistema Nacional de Salud. 2019. Available online: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/ (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- WHO. WHO Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Chronic Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/topics/chronic_diseases/es/ (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Estrategia para el Abordaje de la Cronicidad en el Sistema Nacional de Salud. 2012. Available online: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/ (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Vos, T.; Lim, S.S.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi, M.; Abbasifard, M. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EESE. Instituto Nacional Estadística European Health Interview Survey. Available online: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/EncuestaEuropea/Enc_Eur_Salud_en_Esp_2014.htm (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Årestedt, L.; Persson, C.; Rämgård, M.; Benzein, E. Experiences of encounters with healthcare professionals through the lenses of families living with chronic illness. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 836–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICE Supporting Adult Carers (NG150). Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng150 (accessed on 23 November 2020).

- European Comission Informal care in Europe Exploring Formalisation, Availability and Quality. 2018. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=93 (accessed on 31 January 2021).

- NICE. Dementia: Assessment, Management and Support for People Living with Dementia and Their Carers; (NICE guidline, NG97); NICE: London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97 (accessed on 23 November 2020).

- Sarris, A.; Augoustinos, M.; Williams, N.; Ferguson, B. Caregiving work: The experiences and needs of caregivers in Australia. Health Soc. Care Community 2020, 28, 1764–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confederation of Family Organizations in the European Union Disability. European Charter for family carers. Eur. Community Programme Employ. Soc. Solidar. 2011. Available online: http://www.coface-eu.org/ (accessed on 23 May 2021).

- Årestedt, L.; Persson, C.; Benzein, E. Benzein Living as a family in the midst of chronic illness. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2013, 28, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokorelias, K.M.; Gignac, M.A.M.; Naglie, G.; Cameron, J.I. Towards a universal model of family centered care: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, M.I.M.; Montoya, I.M.; Lozoya, R.M.; Pérez, A.E.; Caballero, V.G.; Hontangas, A.R. Impacto de las intervenciones enfermeras en la atención a la cronicidad en España. Revisión sistemática. Rev. Española Salud Pública 2018, 92, e201806032. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Hajat, C.; Stein, E. The global burden of multiple chronic conditions: A narrative review. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 12, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portillo, M.C.; Senosiain, J.M.; Arantzamendi, M.; Zaragoza, A.; Navarta, M.V.; Díaz de Cerio, S.; Moreno, V. ReNACE Project. Patients and relatives living with Parkinson’s disease: Preliminary results of Phase 1. Enfermería Neurológica 2012, 36, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosio, L.; Navarta-Sánchez, M.V.; Carvajal, A.; Garcia-Vivar, C. Living with Chronic Illness from the Family Perspective: An Integrative Review. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2020, 30, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosio, L.; Senosiain García, J.M.; Riverol Fernández, M.; Anaut Bravo, S.; Díaz De Cerio Ayesa, S.; Ursúa Sesma, M.E.; Caparrós, N.; Portillo, M.C. Living with chronic illness in adults: A concept analysis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015, 24, 2357–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. (Eds.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; Mcinerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schor, E.L.; Cohen, E. Apples and Oranges: Serious Chronic Illness in Adults and Children. J. Pediatrics 2016, 179, 256–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Higgins, J.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.; Welch, V. Chapter 5: Collecting Data. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.2. Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-05 (accessed on 17 December 2020).

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic Analysis. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 160940691773384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V.; Weate, P. Using Thematic Analysis in Sport and Exercise Research; Taylor & Francis (Routledge): London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, K.; Dowell, A.; Nie, J. Attempting rigour and replicability in thematic analysis of qualitative research data; a case study of codebook development. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Moher, D. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, R.D.; Beck, S.; Chou, W.S.; Reblin, M.; Ellington, L. In Their Own Words: Experiences of Caregivers of Adults With Cancer as Expressed on Social Media. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2019, 46, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Borson, S.; Mobley, P.; Fernstrom, K.; Bingham, P.; Sadak, T.; Britt, H.R. Measuring caregiver activation to identify coaching and support needs: Extending MYLOH to advanced chronic illness. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sanjuán, S.; Lillo-Crespo, M.; Cabañero-Martínez, M.J.; Richart-Martínez, M.; Sanjuan-Quiles, Á. Experiencing the care of a family member with Crohn’s disease: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e030625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dekawaty, A.; Malini, H.; Fernandes, F. Family experiences as a caregiver for patients with Parkinson’s disease: A qualitative study. J. Res. Nurs. 2019, 24, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi-tali, S.; Ahmadi, F.; Zarea, K.; Fereidooni-Moghadam, M. Commitment to care: The most important coping strategies among family caregivers of patients undergoing haemodialysis. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2018, 32, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strang, S.; Osmanovic, M.; Hallberg, C.; Strang, P. Heavy and Overloaded Burden in Advanced Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. J. Palliat. Med. 2018, 21, 1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, E.; Wejåker, M.; Danhard, A.; Nilsson, A.; Kristofferzon, M. Living with a spouse with chronic illness—the challenge of balancing demands and resources. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayser, K.; Acquati, C.; Reese, J.B.; Mark, K.; Wittmann, D.; Karam, E. A systematic review of dyadic studies examining relationship quality in couples facing colorectal cancer together. Psycho-oncology 2018, 27, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moral-Fernández, L.; Frías-Osuna, A.; Moreno-Cámara, S.; Palomino-Moral, P.A.; Del-Pino-Casado, R. The start of caring for an elderly dependent family member: A qualitative metasynthesis. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, L.; Jacob, E.; Towell, A.; Abu-qamar, M.; Cole-Heath, A. The role of the family in supporting the self-management of chronic conditions: A qualitative systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusi, G.; Boamah Mensah, A.B.; Boamah Mensah, K.; Dzomeku, V.M.; Apiribu, F.; Duodu, P.A.; Adamu, B.; Agbadi, P.; Bonsu, K.O. The experiences of family caregivers living with breast cancer patients in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2020, 9, 1–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliss, C.L.; Pan, W.; Davis, L.L. Family Involvement in Adult Chronic Disease Care: Reviewing the Systematic Reviews. J. Fam. Nurs. 2019, 25, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcgilton, K.S.; Vellani, S.; Yeung, L.; Chishtie, J.; Commisso, E.; Ploeg, J.; Andrew, M.K.; Ayala, A.P.; Gray, M.; Morgan, D.; et al. Identifying and understanding the health and social care needs of older adults with multiple chronic conditions and their caregivers: A scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhaoyang, R.; Martire, L.M.; Stanford, A.M. Disclosure and Holding Back: Communication, Psychological Adjustment, and Marital Satisfaction Among Couples Coping With Osteoarthritis. J. Fam. Psychol. 2018, 32, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiers, S.J.; Eggenberger, S.K.; Krumwiede, N.K.; Deppa, B. Measuring Family Members’ Experiences of Integrating Chronic Illness Into Family Life: Preliminary Validity and Reliability of the Family Integration Experience Scale:Chronic Illness (FIES:CI). Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2020, 26, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, X.; Chen, J.; Suo, R.; Feng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Jun, Y. The dissimilarity between myocardial infarction patients’ and spouses’ illness perception and its relation to patients’ lifestyle. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, S.H.; Shuster, G.; Lobo, M.L. The family caregiver experience—examining the positive and negative aspects of compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue as caregiving outcomes. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 1424–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Family functioning in the context of an adult family member with illness: A concept analysis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 3205–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosio, L.; Navarta-Sánchez, M.V.; Portillo, M.C.; Martin-Lanas, R.; Recio, M.; Riverol, M. Psychosocial Adjustment to Illness Scale in family caregivers of patients with Parkinson’s Disease: Spanish validation study. Health Soc. Care Community 2020, 29, 1030–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uccheddu, D.; Gauthier, A.H.; Steverink, N.; Emery, T. The pains and reliefs of the transitions into and out of spousal caregiving. A cross-national comparison of the health consequences of caregiving by gender. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 240, 112517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgeson, V.S.; Jakubiak, B.; Van Vleet, M.; Zajdel, M. Communal Coping and Adjustment to Chronic Illness: Theory Update and Evidence. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 22, 170–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, S.; Chen, T.; Eldridge, J.; Thomas, C.A.; Habermann, B.; Tickle-Degnen, L. The self-management balancing act of spousal care partners in the case of Parkinson’s disease. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riffin, C.; Ness, P.H.V.; Iannone, L.; Fried, T. Patient and Caregiver Perspectives on Managing Multiple Health Conditions. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 1992–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faronbi, J.O.; Faronbi, G.O.; Ayamolowo, S.J.; Olaogun, A.A. Caring for the seniors with chronic illness: The lived experience of caregivers of older adults. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 82, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertschi, I.C.; Meier, F.; Bodenmann, G. Disability as an Interpersonal Experience: A Systematic Review on Dyadic Challenges and Dyadic Coping When One Partner Has a Chronic Physical or Sensory Impairment. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 624609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbons, S.W.; Ross, A.; Wehrlen, L.; Klagholz, S.; Bevans, M. Enhancing the cancer caregiving experience: Building resilience through role adjustment and mutuality. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. Off. J. Eur. Oncol. Nurs. Soc. 2019, 43, 101663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, E.; Struckmeyer, K.M. The Impact of Respite Programming on Caregiver Resilience in Dementia Care: A Qualitative Examination of Family Caregiver Perspectives. Inquiry 2018, 55, 46958017751507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chesla, C.A. Parents’ Caring Practices with Schizophrenic Offspring. Qual. Health Res. 1991, 1, 446–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.A. Families Living Well With Chronic Illness: The Healing Process of Moving On. Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S.; Gruen, R.J.; DeLongis, A. Appraisal, coping, health status, and psychological symptoms. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 50, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checton, M.; Greene, K.; Magsamen-Conrad, K.; Venetis, M. Patients’ and Partners’ Perspectives of Chronic Illness and Its Management. Fam. Syst. Health J. Collab. Fam. Healthc. 2012, 30, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alderwick, H.; Dixon, J. The NHS long term plan. BMJ Clin. Res. Ed. 2019, 364, l84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Antonovsky, H.; Sagy, S. The development of a sense of coherence and its impact on responses to stress situations. J. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 126, 213–225. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, J.; Garwick, A. The impact of chronic illness on families: A family systems perspective. Ann. Behav. Med. 1994, 16, 131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Kralik, D.; Van Loon, A.M. Editorial: Transition and chronic illness experience. J. Nurs. Healthc. Chronic Illn. 2009, 1, 113–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Gender and Health. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/gender-and-health (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- Sharma, N.; Chakrabarti, S.; Grover, S. Gender differences in caregiving among family—caregivers of people with mental illnesses. World J. Psychiatry 2016, 6, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertogg, A.; Strauss, S. Spousal care-giving arrangements in Europe. The role of gender, socio-economic status and the welfare state. Ageing Soc. 2020, 40, 735–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.M.; Tyrka, A.R.; Price, L.H.; Carpenter, L.L. Sex differences in the use of coping strategies: Predictors of anxiety and depressive symptoms. Depress. Anxiety 2008, 25, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ham, C. Next steps on the NHS five year forward view. BMJ 2017, 357, j1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Search | Query |

|---|---|

| #1 | (((“FAMILY CARER*”)) OR (“SPOUSE”[All Fields])) OR (“FAMILY CAREGIV*” OR COUPLE OR RELATIVE* OR “INFORMAL CARE*“OR CAREGIVER* [MeSH Terms]))) |

| #2 | ((“LONG* TERM CONDITION*” OR “CHRONIC DISEAS*” OR MULTIMORBIDITY OR “CHRONIC CONDITION*” OR “LONG* TERM ILLNESS*” OR “CHRONIC ILLNESS*”)) |

| #3 | ((NEED* OR COP* OR ADJUST* OR “LIV* WITH” OR EXPERIENCE* OR COEXISTENCE OR ACCEPT* OR ADAPT* OR INTEGRAT* OR PERCEPTION* OR PERSPECTIVE*)) |

| #4 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 |

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Quantitative, qualitative, mixed method studies, statutory documents totally or partially addressing the meaning and the experience of living with LTCs from the family caregiver perspective. | Studies that only show the point of view or the experience from person with LTCs. |

| Studies that include experiences of family caregivers of younger patients (parents). | |

| Studies that include informal caregivers or remunerated caregivers. | |

| Studies that include family caregivers not living together. Studies containing more than two negative responses after assessing methodological quality with the JBI tool, or no ethical approval |

| Theme | Subtheme |

|---|---|

| 1. Attributes |

|

| 2. Mechanisms |

|

| Reference | Country | Sample | Type of Study: Study Design. Collection Methods. | Analysis Method Used | Attributes Found | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| García-San Juan et al., 2019 [32] | Europe | Adults, non-remunerated caregiver, relative caregivers living with those affected by Crohn’s disease. n= 11 | Qualitative. Individual interview, snowballing. Maximum variation sampling | Thematic analyses. | Acceptance, self-management, integration. | It is relevant to know how family careers experience the process, showing a capacity to adapt to the uncertainty of the course of the disease. They find that the intensity of care is a risk factor (hours/week). |

| Dekawaty et al., 2019 [33] | Asia | Family caregivers living with Parkinson’s disease patients. n = 5 | Qualitative. Individual interview. Purposive sampling | Thematic analyses. | Acceptance, coping, self-management, adjustment. | It addresses the meaning of caring for a Parkinson’s disease patient: coping, perceived stressors, family and social support and spiritual and cultural significance. |

| Salehi-Tali et al., 2018 [34] | Asia | Family caregivers living with hemodialysis patients. n = 16 | Qualitative. Individual interview. Purposive sampling | Thematic analyses. | Acceptance, coping. | Addressing spiritual strategies, cultural beliefs may be related to the conception of pain and suffering. It concludes that the outlook of family caregivers is based on innate affection and love for the patient, representing aspects inherent in their beliefs. |

| Strang et al., 2018 [35] | Europe | Personal experience from caring for a COPD patient. n = 35 | Qualitative. Individual interview and focus groups. Maximum variation sampling. | Thematic analyses. | Adjustment. | When the family has adapted, signs of happiness may appear. |

| Eriksson et al., 2019 [36] | Europe | Relatives living with patient with chronic disease. n = 16 | Qualitative. Individual interview. Purposive sampling. | Thematic analyses. | Acceptance, coping, self-management, integration. | The importance of having a support network is essential for adequate coping, the importance of maintaining social relationships and obtaining emotional and instrumental support. |

| Arested et al., 2018 [7] | Europe | Family members of patients ill for more than two years, Swedish-speaking. n = 11 | Qualitative. Narrative interview. Purposive sampling. | Thematic analyses. | Integration. | Need for the family member to be present at meetings with healthcare professionals in order to improve their knowledge of the disease, its management and symptom control. |

| Kayser et al., 2018 [37] | USA | Quantitative observational studies, colorectal cancer, variables included. n = 9 studies. n = 808 participants | Systematic review. | Adjustment. | Women in the role showed higher levels of distress. Dyadic approaches are used with the aim of improving communication skills, mutual emotional support and dyadic coping with common cancer-related stresses. | |

| Moral-Fernández et al., 2018 [38] | America, Canada, Asia, Australia | Studies with new primary caregivers, caring for less than 1 year, research using qualitative methodology. n = 393 participants | Qualitative metasynthesis. | Thematic analyses. | Acceptance, coping, integration. | Addressing the transition to becoming a family caregiver. Acceptance is necessary to cope. |

| Whitehead et al., 2018 [39] | Europe, Australia, USA, Asia | Review of studies in English, qualitative or mixed methods. Excluding end-of-life stage. n = 19 studies. n = 450 participants | Systematic review. | Self-management, integration, adjustment. | Encompasses changes in the context of LTCs’ management from a family perspective. | |

| Ambrosio et al., 2020 [18] | Europe | Review including studies about scales that measure the process of living with the disease. n = 13 | Integrative review. | Acceptance, coping, self-management, integration, adjustment. | This review highlights a need to further study scales that assess explicit aspects of families living with LTCs | |

| Kusi et al., 2020 [40] | Africa, Asia, USA | Review including quantitative, qualitative and mixed-method studies involving family caregivers of breast cancer patients. N = 19 n = 2,330 participants | Systematic review. | Acceptance, coping, self-management. | Addresses the importance of the role of the family caregiver in symptom management. It includes the importance of the economic burden of a sick family member, highlighting the need for policies aimed at considering the family with sick patients. Knowledge as a key aspect in coping with the role of caring. | |

| Gillis et al., 2019 [41] | Europe, USA, Asia | Review of systematic reviews on family participation in the care of patients with chronic diseases. n = 10 n = 22,242 participants | Reviewing the systematic reviews. | Self-management. | Family caregiver was often included as a substitute for the healthcare provider and the healthcare system. Family members were used as surrogates for professionals to provide care, monitor or encourage the patient to achieve goals. | |

| McGliton et al., 2018 [42] | Europe, USA, Asia, New Zeland | Review including studies in adults >55 years, with at least two chronic conditions and their family caregivers. n = 36 n = 137 participants | Scoping review. | Self-management. | It sets out five basic needs common to families and patients: the need for information; coordination of services and support; preventive, maintenance and restorative strategies; training for older adults, careers and health professionals to help manage the complex conditions of older adults; and the need for person-centered approaches. | |

| Zhaoyang et al., 2018 [43] | USA | Couples and patients diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis living together. n = 132 | Quantitative. Observational. Cross sectional. Personal interview. Intentional sample. | Actor-Partner Independence Models | Coping. | Communication as a coping strategy in couples with LTCs. The influence of communicating or suppressing concerns between partners on coping and psychological adjustment to the disease |

| Meiers et al., 2020 [44] | USA | Family member of patient with chronic condition. n = 242 | Quantitative. Cross sectional. Convenience sample. | FIES:CI 1. Descriptive. CES-D | Integration. | Processes and perceptions of family care and living with LTCs also influence the family as a functional system. |

| Qin et al., 2019 [45] | Asia | Couples and patients with myocardial infarct. n = 111 | Quantitative. Observational. Cross sectional. | IPQ-R 2. Descriptive. | Coping. | The same problem may be felt differently (e.g., the degree of symptom control perceived differently between patients and family caregivers). |

| Lynch et al., 2018 [46] | Australia | Adult family caregivers from patients with chronic conditions. n = 168 | Quantitative. Cross sectional, descriptive. Convenience sample. | Descriptive. Pearlin’s model. | Self-management. | Living with an LTC from family perspective is a complex situation largely influenced by the time spent caring. |

| Sarris et al., 2020 [11] | Australia | Adult family caregivers from patients with chronic conditions. English-speaking. n = 12 | Qualitative. Personal interview. Intentional sample. | Thematic analyses. | Adjustment. | It addresses the circumstances that led to the caregiving role, caregiving experience (best and worst) and support needs. |

| Zhang, 2019 [47] | USA | Studies from family functioning, n = 51 | Qualitative. Concept analyses. | Rodger’s methods. | Adjustment. | Identifies attributes of family functioning. |

| Ambrosio et al., 2019 [48] | Europe | Adults, family caregivers from patients with Parkinson’s disease. Spanish-speaking. n = 450 | Quantitative. Cross sectional, descriptive. Consecutive sampling. | PAIS-SR 3. SF-36 4. Descriptive. | Adjustment. | Positive family functioning and increased support can contribute to less perceived caregiver strain and greater perceived well-being. |

| Ucheddu et al., 2018 [49] | Europe | 50 years of age or older and who had a spouse who also participated in the SHARE survey during the same period and not institutionalized. | Quantitative. Cross sectional, retrospective. Convenience sample. | Fixed-effects regression models. | Acceptance. | Most informal carers do not have the option to take on the role of carer; it is a situation that arises. |

| Helgeson et al., 2019 [50] | Not specified | Review from studies about community coping and adjustment for adults. | Review. Theory Update and Evidence | Coping, self-management. | Describes the process and construction of the theory of coping with chronic illness and the management of chronic illness together with the patient and family caregiver | |

| Berger et al., 2019 [51] | USA | Spousal care partners of people with Parkinson’s disease. n = 20 | Qualitative. Grounded theory. Pourposeful sample | Thematic analyses. Glaser and Strauss framework. | Acceptance, coping and self-management. | Caring for patients requires caregivers to take care of themselves physically and emotionally. To maintain a proper balance, the inherent social role of the human being needs to be maintained |

| Riffin et al., 2018 [52] | USA | Family caregivers living with patients of chronic conditions. n = 20 | Qualitative. Individual interview. Convenience sample. | Thematic analyses. | Self-management. | This study shows the advantages of using a dyadic approach to better understand care relationships. |

| Faronbi et al., 2019 [53] | Africa | Family caregivers living with seniors with chronic conditions. n = 15 | Qualitative. Individual interview. Convenience sample. | Thematic analyses. | Self-management. | Family caregivers provide a range of support to their loved ones ranging from help with daily living activities, financial, psychological and spiritual support. |

| Bertschi et al., 2021 [54] | Europe | Studies of relatives were one of them have LTCs. n = 36 | Systematic review. | Acceptance, coping, adjustment. | Dyadic coping and communication help to buffer the stress experienced by couples due to chronic deteriorating health. | |

| Gibbons et al., 2019 [55] | USA | Family caregivers and patients with cancer. n = 12 | Mixed methods. Qualitative and quantitative. | Thematic analyses. FCI scale 5, neuro-QoL 6, MHC-SF 7. | Coping, adjustment. | The diagnosis of LTCs (cancer) affects interpersonal relationships, social networks, finances and functioning of patients and their family caregivers |

| Roberts and Struckmeyer., 2018 [56] | USA | Patient–caregiver dyads of multiple health conditions. n = 20 | Part of a mixed-methods study. Qualitative. Individual interview. | Constant comparative method. | Acceptance, adjustment. | Many caregivers report that they derive significant emotional and spiritual rewards from their caregiving role, and others also experience physical and emotional problems directly related to the stress and demands of daily caregiving. |

| Themes and Subthemes | Deductive/ Inductive | Quotes (Q) and Text (T) for Findings. (Reference. Page) |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: Attributes | ||

| 1.1. Acceptance | Deductive | T1. “when an individual has accepted the reality of situation and has ideas about the cause of the problem, accepting the reality of life and all experiences: good or bad” … “is a final stage of adjustment”. ([33], p.3) |

| Q1. “Yes, what else can we do? Just accept it submit to a fate like this.” ([33], p.4) | ||

| T2. “Despite describing a situation that was imposed upon them, several of the informants still discussed accepting these changes to daily life. The transition had been successive; they had time to adapt. Even in this exposed situation, some still felt a mutual responsibility. In certain aspects, their relationship had even become strengthened, as helping their loved one and being needed were important to them. Acceptance, although not easy, was a viable coping strategy. Those who emphasized acceptance described how they actively tried to focus on attainable goals rather than letting frustration overwhelm the situation”([35], p.2) | ||

| T3. “The participants both accepted and distanced themselves from the constant challenges of everyday life.” ([36], p.6) | ||

| Q2. “We’ve both gotten to the age, so we’re fully aware that everything might not be like before... it’s well... almost a sort of acceptance” ([33], p. 5) | ||

| T4. “Acceptance is to assume and normalize the role of caregiver, being the final stage of conversion into family caregiver” They mention the new situation that they have to assume and describe the day of onset of their family member’s illness as crucial to their lives and as unpredictable. ([38], p. 5) | ||

| T5. “Given all the problems and needs that family caregivers have, they show different ways of tackling the changes that occur when they begin caring for their relatives. Among these ways that can be adopted of tackling the issue, we find there is generally acceptance of or resistance to the care situation” ([38], p. 5) | ||

| T6. “acceptance of the disability and its consequences also seemed to favor positive dyadic coping. For instance, Smith and Shaw (2017) concluded that PD couples fared well when they assimilated PD into their lives, that is, when couples acknowledged that PD required changes to their lifestyle. This allowed patients to retain more agency and thus provided them with more opportunities to be involved in coping. In contrast, lack of acceptance hindered constructive dyadic coping.” ([54], p. 16) | ||

| T7. “Acceptance is the ability to step back from a caregiving situation to assess the entirety of the situation” ([56], p. 4) | ||

| Q3. “I mean I feel like I’m doing something, trying to do something. There are lots of days when you’re not doing a good job, but at least you’re trying” ([56], p. 8) | ||

| 1.2. Coping | Deductive | T8. “Coping is dynamic and involves aspects such as the nature of the stressor or the stimulus itself, personal characteristics and external resources such as the support received” ([33], p. 8) |

| T9. “Coping is achieved by balancing a sense of purpose in daily activities while maintaining control, even though the family member’s health is constantly changing” ([36], p. 2) | ||

| T10. “to implement strategies to minimize the negative effects of caregiving that allow them to cope with the problems that arise during care” ([38], p. 11) | ||

| T11. “Following trying to normalise the situation of care, caregivers may adopt coping strategies focused on solving problems, which increases safety in the care they provide.” ([38], p. 10) | ||

| Q4. “I think that every time we get a little bit further away, it makes us more secure. It is like dangerous waters and we are gradually sailing out of them.” ([38], p. 10) | ||

| T12. “acceptance of the disability and its consequences also seemed to favor positive dyadic coping” ([54], p. 16) | ||

| T13. “couples fared well when they assimilated PD into their lives, that is, when couples acknowledged that PD required changes to their lifestyle. This allowed patients to retain more agency and thus provided them with more opportunities to be involved in coping.” ([54], p. 16) | ||

| T14. “concepts of self-efficacy, hopefulness, and stress resistance become necessary components of coping capabilities, a complex construct which is often referred to as resilience” ([56], p. 1) | ||

| T15. “Caregiver resilience may be termed as the use of successful coping strategies used by informal and formal caregivers, shifting from the burden perspective to a resilience perspective.” ([56], p. 1) | ||

| T16. “religious coping such as putting one’s faith in God was vital in improving the quality of life among caregivers. Two of the studies further reported that caregivers reported that being religious provided them with meaning in their caregiving roles”. ([40], p. 15) | ||

| 1.3. Self-Management | Deductive | T17. “importance of support from the formal care systems to help them manage patients’ symptoms in the home setting” ([40], p. 14). |

| T18. “Studies in this review highlighted the significant role played by caregivers in symptom management” ([36], p. 15) | ||

| T19. “Family members were used as substitutes for professionals to deliver needed care, monitor, or encourage the patient to obtain goals.” ([41], p. 18) | ||

| T20. “They experienced difficulties managing the care of their family member, but they felt they had no other option. Some caregivers found themselves ensuring their family members kept their appointments, took over medication and nutrition management, and were instrumental in ensuring the person maintained their dignity, particularly at the end of life.” ([42], p. 27) | ||

| T21. “The increase in additional instrumental activities of daily living inherent in the family caregiver role increases the difficulty in finding a balance between participation in social, leisure, and productive activities” ([51], p. 7) | ||

| Q5. “I’m not very good at cutting out time for myself and I have to do it first thing in the morning or my day goes to heck in a hand basket…it’s very empowering to take care of yourself first thing, and then, once you’ve taken care of yourself, then you can take care of all the many disasters that we face every day.” ([51], p. 6) | ||

| T22. “Family caregivers find themselves balancing the resources and demands available to them to manage their daily lives” ([36], p. 6) | ||

| T23. “Previous knowledge on breast cancer aided caregivers to cope effectively in their caring role” ([40], p. 15) | ||

| T24. “Adapting to constant changes and an uncertain future”([36], p. 5) | ||

| T25. “Family support for patients with CD greatly contributes to the management of such a condition” ([32], p. 6). “information and support that would enable the carer and patient to plan for events that might arise in the future ”([32], p. 6) | ||

| T26. “Caring for a family member with Parkinson’s disease keeps the caregiver at home for a long time. This situation changes the caregiver’s course of action, including performing health self-examinations…[caregivers] generally spend their time giving treatment and neglect to check their own health”. ([33], p. 8) | ||

| T27. “family collaboration in self-management has been related to self-management capacity.” ([39], p. 5) | ||

| T28. “caregivers reported a moderate to severe decline in physical health”([40], p. 16). “caregivers usually decreased their working hours or lost paid jobs as a result of the caregiving role” ([40], p. 14) | ||

| T29. “patients and caregivers became anxious as they were uncertain whether they were making the right choices” (37, p. 27). “Taking on this coordinator role was a source of tension between some older adults and their caregivers as they had conflicting ideas about future plans, and how to stay healthy and safe” ([42], p. 27) | ||

| T30. “Involvement of wider family members helped families to maintain a positive approach and to negotiate how to promote self-management” ([39], p. 9) | ||

| T31. “This balancing act was complicated, because it could change from day to day depending on their spouse’s condition”([36], p. 4). “participants had limited time on their own.” ([36], p. 6) | ||

| 1.4. Integration | Deductive | T32. “in order to maintain the process and balance of family life, roles must be adjusted when the family system encounters challenges” ([32], p. 6) |

| T33. “family perspective involves balancing daily chores, maintaining the support of the social network and adapting to constant changes and uncertain future by balancing” ([36], p. 6) | ||

| T34. “Although the participants accepted the spouse’s illness, they were unsure about how to handle their situation. Some distanced themselves from it all, mentioning that they did not think so much about the illness. They tried to live like normal, because this had a value in itself. However, it was not obvious to all participants how they practically handled their circumstances.” ([36], p. 6) | ||

| Q6. “what do I do? I don’t know, I don’t do anything special”. ([36], p. 6) | ||

| T35. “families living with LTCs are required to co-created a context for living their everyday lives, and this is a continuous ongoing process” ([7], p. 3) | ||

| T36. “personal growth and satisfaction that the care task reports to them, and how it helps them value day-to-day things” ([38], p. 9) | ||

| T37. “family created an environment that valued involvement of the family member in everyday activities and normalisation or striving for as normal a lifestyle as possible” ([39], p. 10) | ||

| T38. “processes used by family members to adapt to the realities and uncertainties of chronic illness across the evolving family life cycle in the context of chronic illness.” ([44], p. 3) | ||

| T39. “Families may create positive meaning in the context of the chronic illness experience over time, learn to incorporate illness management into family routines, make adaptations to construct their own subjective illness meanings, and develop strategies for coping with illness management”. ([44], p. 2) | ||

| T40. “[Families] evolve patterns of caring practices [57] to normalize the illness and family life surrounding illness management”. ([44,57], p. 2) | ||

| Q7. “The joy I feel is when I see that she is feeling better, for example, that her old self may show up sometimes. It makes me and her happy. So, you have got to enjoy these little moments.” ([35], p. 3) | ||

| T41. “Still, many informants also depicted moments of happiness. Several authors have identified universal sources of meaning, and such sources are still available, even in the case of severe illness. It was not surprising that, for example, children and friends were mentioned in a positive context, as good relations are a vital source of meaning. However, to gain access to such sources of meaning, the family had to adapt to the new situation. When this was the case, moments of joy were possible.” ([35], p. 4) | ||

| 1.5. Adjustment | Deductive | T42. “The caregivers’ adaptation to the condition of their family member with Parkinson’s disease is expressed through the acceptance of the condition and an effort to live with the situation.” ([33], p. 3) |

| T43. “Psychosocial adjustment to a complex and disabling long-term condition like PD is a complex, dynamic, cyclical and interactive process in which different factors and mechanisms play key roles” ([48], p. 2) | ||

| T44. “Adjustment to a “new normal” requires patients with chronic health conditions to cope with disabling health impairments on a daily basis, for example, by following a treatment regimen, managing the financial impact of treatments, or changing leisure time activities and social interactions to accommodate the impairment” ([54], p. 2) | ||

| T45. “Multiple factors make the adjustment to the caregiving role particularly hard, as the caregiver balances this role with other demands, including child rearing, careers, and relationships” ([56], p. 1) | ||

| Q8. “Some participants had confidence in their ability to handle the situation, and others thought it would work out in the future. As new problems arose, the participants found it natural to identify practical solutions.” ([36], p. 6) | ||

| T46. “high motivation to adhere to his or her caregiving role. In this situation, cultural and religious beliefs and values are considered as incentives for caregivers so that instead of thinking about the difficulties of providing care, caregivers adhere to their cultural and religious beliefs as well as the value of caregiving.” ([34], p. 8) | ||

| T47. “family functioning is defined as family members’ ability to maintain cohesive relationships with one another, fulfill family roles, cope with family problems, adjust to new family routines and procedures, and effectively communicate with each other”. ([47], p. 9) | ||

| T48. “The mere presence of a family caregiver across the cancer trajectory can have a positive impact on the patient’s life and the adoption of healthier habits” ([50], p. 1). “developing interventions at a dyadic level, researchers and medical research partners have the potential to encourage dyadic resilience and sustain partnerships from cancer treatment into survivorship.” ([50], p. 22) “provides a unique opportunity to build on the positive tendencies inherent in dyadic partnerships already engaging in role adjustment and mutuality development in the midst of uncertainty” ([55], p. 2) | ||

| Theme 2. Mechanisms | ||

| 2.1. Awareness of the situation of change created by an LTC. | Inductive | Q9. “I will serve him (patient) by all means... I have never said I’m tired because he is not only my husband but ‘... also because he is a of wealth and happiness for me and my kids.’ I have a lot of respect for his dignity and status (Wife, 10 years of care).” ([34], p. 4) |

| T50. “caregivers experienced a loss of normal life.” ([40], p. 14) | ||

| T51. “How even the most successful suffer tremendous stress due to illness and changing life circumstances” ([55], p. 21) | ||

| T52. “The caregiver must make timely adaptations to adopt the caregiver role within the family system, especially during times of severe exacerbation of the illness.” ([32], p. 6) | ||

| T53. “it is important to recognize that what is important for caregivers‘ health is not only transitioning into caregiving, but also the duration of care. In other words, some caregivers could easily cope with a relative short time of caregiving, but beyond that time it starts to have its negative consequences on individual health.” ([49], p. 8) | ||

| T54. “Participants stated that they experience a disruption in the family process due to the inability to effectively combine the caregiving activities with their family and personal daily demand. The daily routine of care of the elderly impedes on caregivers’ attendance to their own daily business, family matters and other personal obligations.” ([53], p. 3) “Caregivers in this study spend substantial numbers of hours in providing care daily for their sick elderly. They assist in activities of daily living such as feeding, grooming, changing of position, medication and running errands. Almost one-third of the respondents in this study claimed that they spend almost the entire day caring for the sick elderly” ([53], p. 5) | ||

| T55. “A certain concern or burden is evident due to the constant apprehension about the present and future of their affected family member” ([32], p. 6) | ||

| T56. “in different health conditions, partners often feel overwhelmed by their new “identity” as caregivers and with caregiving tasks”. ([54], p. 17) | ||

| Q10. “becoming a caregiver is not a normatively expected transition and, therefore, is not preceded by systematic preparation” ([49], p. 2) | ||

| 2.2. Personal networks | Inductive | T57. “In fact, a positive family functioning and a greater support between family members may contribute to a lower perception of burden in caregivers and to a higher perception of well-being.” ([18], p. 1) |

| T58.“information and support that would enable the carer and patient to plan for events that might arise in the future” ([32], p. 6) | ||

| T59.“collaboration was necessary for the family to feel secure in their ability to handle life with illness in the best way possible. When the families felt they could collaborate in the caring process, it contributed to feelings of confidence, and that their input could influence and contribute in the situation” ([7], p. 12) | ||

| T60. “family collaboration in self-management has been related to self-management capacity.” ([39], p. 5) | ||

| T61.“ Individuals in stressful situations such as caregiving can benefit from social support networks as they can provide the resources that help them manage their situation” ([56], p. 4) | ||

| Q11. “The caregiver group is a godsend, because sometimes you’ve just got to dump and you can do it there. It makes me feel better because I know I’m not alone. Every other one of those wives is going through what I’m going through, it’s the neatest, tiredest looking group of women I’ve seen. We have days when we laugh and cry, it’s like this little amount of light. Without the groups, I wouldn’t have made it.” ([56], p. 7) | ||

| Q12. “It does feels really good to just get a break, I just feel guilty, I’m not gonna lie.” ([56], p. 7) | ||

| T62. “The study respondents were unanimous in reporting that their feelings of isolation were amplified with the increase in their caregiving responsibilities. “([56], p. 5) | ||

| 2.3. Information and education about the LTCs. | Inductive | T63. “Need for information about the illness, care and prognosis of the family member, and the training to develop the necessary skills to perform the task of caring in the best possible way, is reflected in the requests of family caregivers to health personnel” ([38], p. 9) |

| T64. “Family carers in the present study assumed the provision of care with no knowledge or experience in dealing with the disease, the decision-making, the management of the complications and the interpersonal challenges yet to come, all of which could be facilitated if early-stage information was available regarding the progression of the disease, information and support that would enable the carer and patient to plan for events that might arise in the future” ([32], p. 5) | ||

| T65. “The provision of informational support aided in decreasing caregiving burden among the caregivers.” ([40], p. 17) | ||

| 2.4. Personal conditions | Inductive | T66. “The results showed that most participants have reliable coping mechanisms such as accepting their parents’ conditions and relating the event to spiritual aspects.” ([33], p. 7) |

| T67. “religious coping such as putting one’s faith in God was vital in improving the quality of life among caregivers. Two of the studies further reported that caregivers reported that being religious provided them with meaning in their caregiving roles”... “Previous knowledge on breast cancer aided caregivers to cope effectively in their caring role” ([40], p. 15) | ||

| T68. “The caregiver... must have a high motivation to adhere to his or her caregiving role. In this situation, cultural and religious beliefs and values are considered as incentives for caregivers so that instead of thinking about the difficulties of providing care, caregivers adhere to their cultural and religious beliefs as well as the value of caregiving”. ([34], p. 4) | ||

| T69. “Their beliefs that caring for an older adult is an investment serve as a motivation to continue despite all odds”. ([53], p. 7) | ||

| T70. “Financial challenges such as lack of transportation, loss of a paid job, and high treatment cost were also fundamental sources of stress for caregivers” ([40], p. 15) | ||

| T71. “Families who view the providing of care for the elderly as an obligation experienced pride and increased satisfaction, and expressed a positive response.” ([33], p. 8) | ||

| 2.5. Attitude to life | Inductive | T72. “Involvement of wider family members helped families to maintain a positive approach and to negotiate how to promote self-management” ([39], p. 9) |

| T73. Earlier experiences of success in life or of being optimistic served as resources that the participants used to manage daily life. ([36], p. 5). Q 13. “I’m a pretty positive person…I don’t let the situation get the better of me.” ([36], p. 5) | ||

| T74. “They seek to reduce the negative effects by trying to take care of strategies to mantain emotional positivity… being positive and optimistic… mantain spiritual support” ([38], p. 10) | ||

| T75. “[Acceptance] It is characterised by a positive attitude, recognition or appreciation of individual values and acknowledgement of one’s own behaviour” ([33], p. 7) | ||

| 2.6. Communication. | Inductive | T76. “Changes in openness were described within some of the families and communication patterns were altered”. ([35], p. 2) |

| T77. “Family functioning influences family member health, and discrepant perceptions of family functioning contribute to poor psychological health.” ([44], p. 2) | ||

| T78. “However, communication was also described as crucial to the relationship” ([36], p. 7) | ||

| T79. “Those at risk for relationship distress could be taught skills that will help them cope, including helpful communication skills such as validation, as this was found to be associated with reduced distress” ([37], p. 14) | ||

| T80. “Family Health Conversations (FHC) are an appropriate way to involve families and attain a family centered care, let them tell their story, and enhance family well-being...It can also make it easier for families to handle challenges faced due to illness, and therefore, it also contributes to overall family well-being” ([7], p. 27) | ||

| Q13. “We try to talk more, not less. For you need to talk about things to lighten them up, otherwise. Because there’s always something to take care of.” ([36], p. 5) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marín-Maicas, P.; Corchón, S.; Ambrosio, L.; Portillo, M.C. Living with Long Term Conditions from the Perspective of Family Caregivers. A Scoping Review and Narrative Synthesis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7294. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147294

Marín-Maicas P, Corchón S, Ambrosio L, Portillo MC. Living with Long Term Conditions from the Perspective of Family Caregivers. A Scoping Review and Narrative Synthesis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(14):7294. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147294

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarín-Maicas, Patricia, Silvia Corchón, Leire Ambrosio, and Mari Carmen Portillo. 2021. "Living with Long Term Conditions from the Perspective of Family Caregivers. A Scoping Review and Narrative Synthesis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 14: 7294. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147294

APA StyleMarín-Maicas, P., Corchón, S., Ambrosio, L., & Portillo, M. C. (2021). Living with Long Term Conditions from the Perspective of Family Caregivers. A Scoping Review and Narrative Synthesis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), 7294. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147294