Developing and Disseminating Physical Activity Messages Targeting Parents: A Systematic Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identifying the Relevant Search Records

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Peer-Reviewed Databases

2.4. Expert Consultations

2.5. Record Selection and Charting the Data

2.6. Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting Results

3. Results

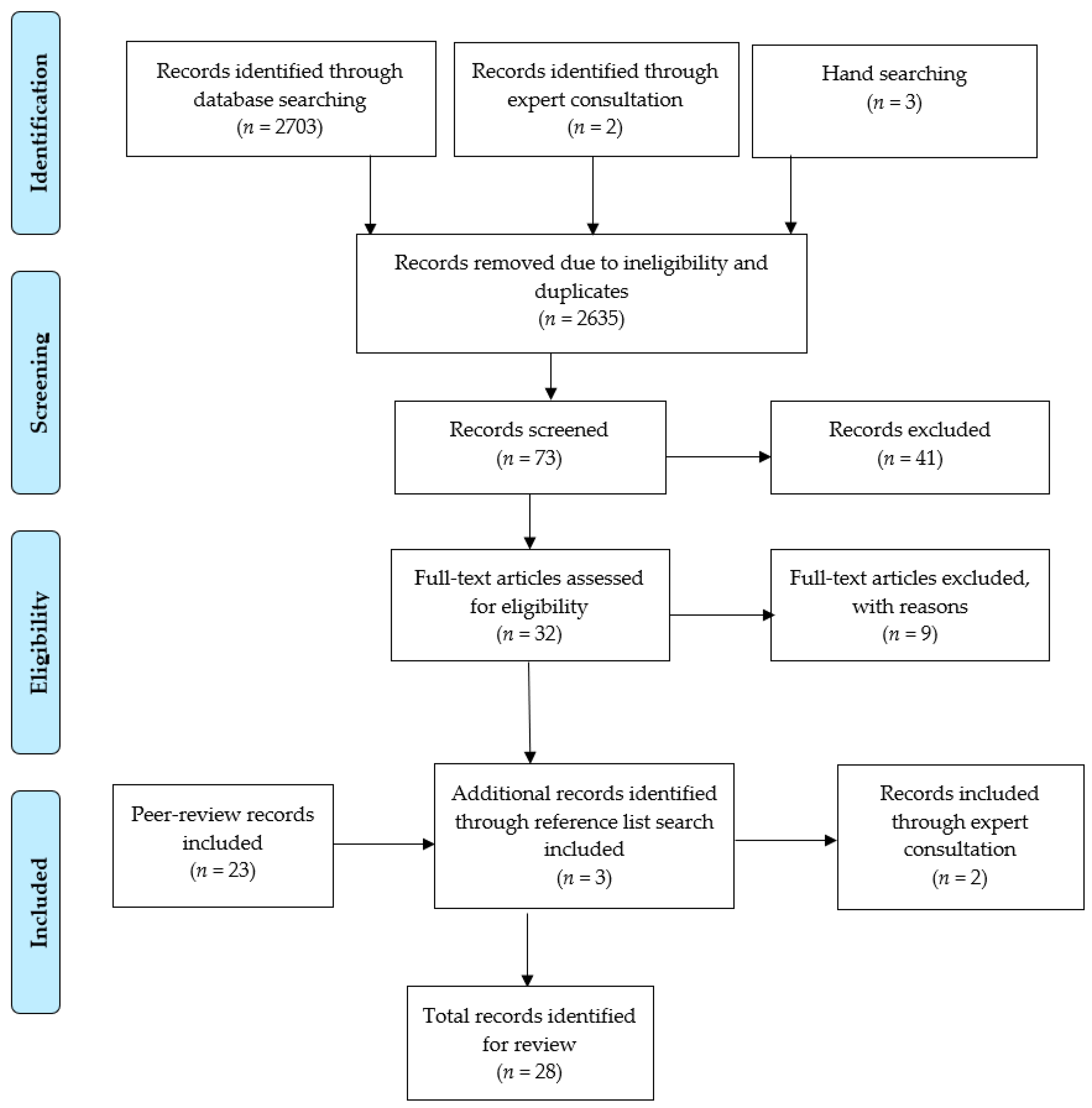

3.1. Search Results Regarding Parents

3.1.1. Evidence Characteristics

3.1.2. Summary of Main Findings: Development of PA Messages Targeting Parents

Theme 1: Message Persuasion

Theme 2: Messages That Consider Barriers to Parent Support for PA

Theme 3: Messages That Target Parents’ Attitudes

Dissemination of PA Messages Targeting Parents

Theme 1: Dissemination to Enhance Cognitive Processing

Theme 2: Social Marketing Strategies to Enhance Dissemination

Theme 3: Messages That Target the Dissemination Preferences and Suggestions of Parents

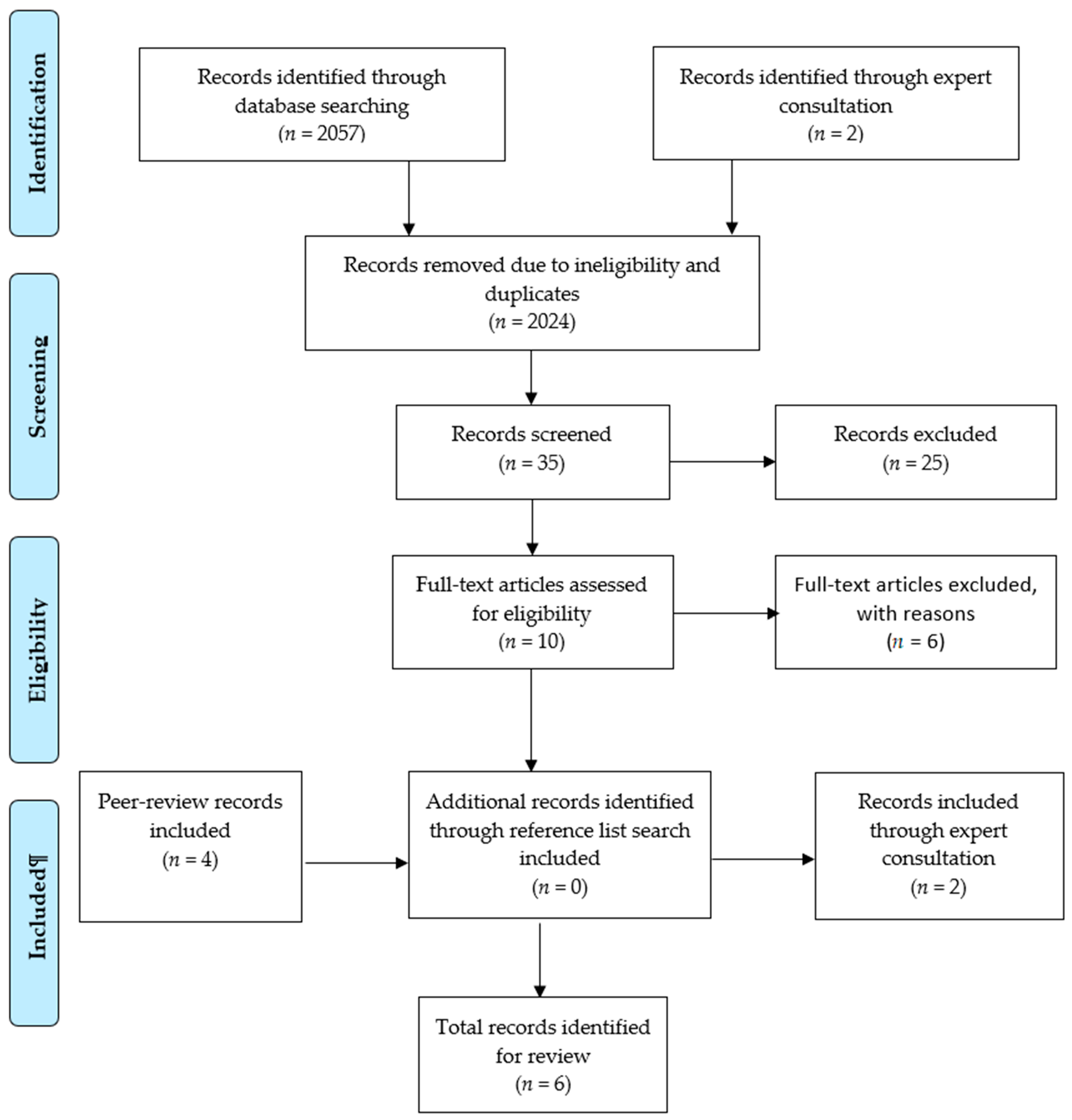

3.2. Search Results Regarding Parents of CWD

3.2.1. Evidence Characteristics

3.2.2. Summary of Main Findings: Development of Physical Activity Messages Targeting Parents of CWD

Theme 1: Common Barriers to Parent Support for PA among Parents of CWD

Dissemination of Physical Activity Messages Targeting Parents of CWD

Theme 1: Dissemination Preferences and Suggestions of Parents of CWD

4. Discussion

4.1. Strategies Regarding the Development of Physical Activity Messages

4.2. Unique Message Development Considerations for Parents of CWD

4.3. Strategies Regarding the Dissemination of Physical Activity Messages

4.4. Unique Message Dissemination Considerations for Parents of CWD

4.5. Strength and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roberts, K.C.; Yao, X.; Carson, V.; Chaput, J.-P.; Janssen, I.; Tremblay, M.S. Meeting the Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Youth. Health Rep. 2017, 28, 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- The Child & Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. 2016. Available online: https://www.childhealthdata.org/learn-about-the-nsch/NSCH (accessed on 31 December 2020).

- Bloemen, M.; Van Wely, L.; Mollema, J.; Dallmeijer, A.; De Groot, J. Evidence for increasing physical activity in children with physical disabilities: A systematic review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2017, 59, 1004–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, S.L.; Rhodes, R.E. Parental Correlates of Physical Activity in Children and Early Adolescents. Sports Med. 2006, 36, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Spence, J.C.; Berry, T.; Deshpande, S.; Faulkner, G.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; O’Reilly, N.; Tremblay, M.S. Predicting Changes Across 12 Months in Three Types of Parental Support Behaviors and Mothers’ Perceptions of Child Physical Activity. Ann. Behav. Med. 2015, 49, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, J.; Goodwin, D.L. Physical Education for Students with Spina Bifida: Mothers’ Perspectives. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2007, 24, 38–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beets, M.W.; Cardinal, B.J.; Alderman, B. Parental Social Support and the Physical Activity-Related Behaviors of Youth: A Review. Health Educ. Behav. 2010, 37, 621–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalchuk, K.; Crompton, S. Living with disability series social participation of children with disabilities. Can Soc. Trends. 2009, 88, 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Zecevic, C.A.; Tremblay, L.; Lovsin, T.; Michel, L. Parental Influence on Young Children’s Physical Activity. Int. J. Pediatr. 2010, 2010, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gainforth, H.L.; Jarvis, J.W.; Berry, T.R.; Chulak-Bozzer, T.; Deshpande, S.; Faulkner, G.; Rhodes, R.E.; Spence, J.C.; Tremblay, M.S.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E. Evaluating the ParticipACTION “Think Again” Campaign. Health Educ. Behav. 2015, 43, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latimer, A.E.; Brawley, L.R.; Bassett, R.L. A systematic review of three approaches for constructing physical activity messages: What messages work and what improvements are needed? Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, A.E.; Nelson, D.E.; Pratt, M.; Matsudo, V.; Schöeppe, S. Dissemination of Physical Activity Evidence, Programs, Policies, and Surveillance in the International Public Health Arena. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2006, 31, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhman, M.E.; Potter, L.D.; Nolin, M.J.; Piesse, A.; Judkins, D.R.; Banspach, S.W.; Wong, F.L. The influence of the VERB campaign on children’s physical activity in 2002 to 2006. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, T.R.; Craig, C.L.; Faulkner, G.; Latimer, A.; Rhodes, R.; Spence, J.C.; Tremblay, M.S. Mothers’ Intentions to Support Children’s Physical Activity Related to Attention and Implicit Agreement with Advertisements. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2012, 21, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarvis, J.W.; Rhodes, R.E.; Deshpande, S.; Berry, T.R.; Chulak-Bozzer, T.; Faulkner, G.; Spence, J.C.; Tremblay, M.S.; Lati-mer-Cheung, A.E. Investigating the role of brand equity in predicting the relationship between message exposure and paren-tal support for their child’s physical activity. Soc. Mark Q. 2014, 20, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Murumets, K.; Faulkner, G. The National Voice of Physical Activity and Sport Participation in Canada. Implement. Phys. Act. Strateg. 2014, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bassett-Gunter, R.; Ruscitti, R.; Latimer-Cheung, A.; Fraser-Thomas, J. Targeted physical activity messages for parents of children with disabilities: A qualitative investigation of parents’ informational needs and preferences. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 64, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, V.; Santos, S.; Gomes, F.; Peralta, M.; Marques, A. Formal and informal physical activity of students with and without intellectual disabilities: A Comparative study. Sports Phys. Act. 2016, 2, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Siebert, E.A.; Hamm, J.; Yun, J. Parental influence on physical activity of children with disabilities. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2017, 64, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanna, S.; Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K.; Rhodes, R.E.; Bassett-Gunter, R. A pilot study exploring the use of a telephone-assisted planning intervention to promote parental support for physical activity among children and youth with disabilities. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2017, 32, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larocca, V.; Latimer-Cheung, A.; Bassett-Gunter, R. The effects of physical activity messages on physical activity support behaviours and motivation among parents of children with disabilities. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2019, 51, 214. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, C.; Baker, G.; Mutrie, N.; Niven, A.; Kelly, P. Get the message? A scoping review of physical activity messaging. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.; Mallick, K.; Monforte, J.; Foster, C. Disability, the communication of physical activity and sedentary behaviour, and ableism: A call for inclusive messages. Br. J. Sports Med. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavis, J.N.; Robertson, D.; Woodside, J.M.; McLeod, C.; Abelson, J. How Can Research Organizations More Effectively Transfer Research Knowledge to Decision Makers? Milbank Q. 2003, 81, 221–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Urzo, K.A.; Man, K.E.; Bassett-Gunter, R.L.; E Latimer-Cheung, A.; Tomasone, J.R. Identifying “real-world” initiatives for knowledge translation tools: A case study of community-based physical activity programs for persons with physical disability in Canada. Transl. Behav. Med. 2018, 9, 797–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, K.; Stapleton, J.; Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Hanning, R.M.; Leatherdale, S.T. Applying systematic review search methods to the grey literature: A case study examining guidelines for school-based breakfast programs in Canada. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassett-Gunter, R.; Stone, R.; Jarvis, J.; Latimer-Cheung, A. Motivating parent support for physical activity: The role of framed persuasive messages. Health Educ. Res. 2017, 32, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.2 (Updated February 2021); Cochrane: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- Bhatnagar, A.; Ghose, S. An Analysis of Frequency and Duration of Search on the Internet. J. Bus. 2004, 77, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, J.W.; Gainforth, H.L.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E. Investigating the effect of message framing on parents’ engagement with advertisements promoting child physical activity. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2014, 11, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, F.; White, L.; Riazi, N.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Tremblay, M.S. Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Youth: Exploring the perceptions of stakeholders regarding their acceptability, barriers to uptake, and dissemination. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, L.L.; Hector, D.; Saleh, S.; King, L. Australian Middle Eastern parents’ perceptions and practices of children’s weight-related behaviours: Talking with Parents’ Study. Health Soc. Care Community 2015, 24, e63–e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, A.; Bowen, J.; Corsini, N.; Gardner, C.; Golley, R.; Noakes, M. Understanding parent concerns about children’s diet, activity and weight status: An important step towards effective obesity prevention interventions. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 13, 1221–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, R.; Jones, R.; Swann, C.; Christian, H.; Sherring, J.; Shilton, T.; Okely, A. Exploring Stakeholders’ Perceptions of the Acceptability, Usability, and Dissemination of the Australian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for the Early Years. J. Phys. Act. Health 2020, 17, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentley, G.F.; Jago, R.; Turner, K.M. Mothers’ perceptions of the UK physical activity and sedentary behaviour guidelines for the early years (Start Active, Stay Active): A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e008383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistry, C.D.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E. Mothers’ beliefs moderate their emotional response to guilt appeals about physical ac-tivity for their child. Int. J. Commun. Health. 2014, 2, 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Crozier, A.J.; Berry, T.R.; Faulkner, G. Examining the Relationship between Message Variables, Affective Reactions, and Parents’ Instrumental Attitudes toward Their Child’s Physical Activity: The “Mr. Lonely” Public Service Announcement. J. Health Commun. 2018, 23, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, G.; Solomon, V.; Berry, T.; Deshpande, S.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Rhodes, R.; Spence, J.; Tremblay, M.S. Examin-ing the potential disconnect between parents’ perceptions and reality regarding the physical activity levels of their children. JARC 2014, 5, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Price, S.M.; Huhman, M.; Potter, L.D. Influencing the Parents of Children Aged 9–13 Years: Findings from the VERB™ Campaign. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 34, S267–S274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett-Gunter, R.; Rhodes, R.; Sweet, S.; Tristani, L.; Soltani, Y. Parent Support for Children’s Physical Activity: A Qualitative Investigation of Barriers and Strategies. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2017, 88, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bélanger-Gravel, A.; Cutumisu, N.; Gauvin, L.; Lagarde, F.; Laferté, M. Correlates of Initial Recall of a Multimedia Communication Campaign to Promote Physical Activity among Tweens: The WIXX Campaign. Health Commun. 2016, 32, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, C.L.; Bauman, A.; Gauvin, L.; Robertson, J.; Murumets, K. ParticipACTION: A mass media campaign targeting parents of inactive children; knowledge, saliency, and trialing behaviours. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2009, 6, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, C.; Campbell, K.; Hesketh, K.D. Key Messages in an Early Childhood Obesity Prevention Intervention: Are They Recalled and Do They Impact Children’s Behaviour? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asbury, L.D.; Wong, F.L.; Price, S.M.; Nolin, M.J. The VERB™ Campaign: Applying a Branding Strategy in Public Health. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 34, S183–S187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhman, M.; Berkowitz, J.M.; Wong, F.L.; Prosper, E.; Gray, M.; Prince, D.; Yuen, J. The VERB™ Campaign’s Strategy for Reaching African-American, Hispanic, Asian, and American Indian Children and Parents. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 34, S194–S209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, F.; Huhman, M.; Asbury, L.; Bretthauer-Mueller, R.; McCarthy, S.; Londe, P.; Heitzler, C. VERB™—A social marketing campaign to increase physical activity among youth. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2004, 1, A10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bellows, L.; Silvernail, S.; Caldwell, L.; Bryant, A.; Kennedy, C.; Davies, P.; Anderson, J. Parental Perception on the Efficacy of a Physical Activity Program for Preschoolers. J. Community Health 2010, 36, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellows, L.; Spaeth, A.; Lee, V.; Anderson, J. Exploring the Use of Storybooks to Reach Mothers of Preschoolers with Nutrition and Physical Activity Messages. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2013, 45, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Borra, S.T.; Kelly, L.; Shirreffs, M.B.; Neville, K.; Geiger, C.J. Developing health messages: Qualitative studies with children, parents, and teachers help identify communications opportunities for healthful lifestyles and the prevention of obesity. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2003, 103, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Rhodes, R.E.; Kho, M.E.; Tomasone, J.R.; Gainforth, H.L.; Kowalski, K.; Nasuti, G.; Perrier, M.-J.; Duggan, M.; The Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines Messaging Recommendation Workgroup. Evidence-informed recommendations for constructing and disseminating messages supplementing the new Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, R.L., Jr.; Marker, A.M.; Allen, H.R.; Machtmes, R.; Han, H.; Johnson, W.D.; Schuna, J.M., Jr.; Broyles, S.T.; Tudor-Locke, C.; Church, T.S.; et al. Parent-Targeted Mobile Phone Intervention to Increase Physical Activity in Sedentary Children: Randomized Pilot Trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2014, 2, e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, S.; Ortega, A.; Kanter, R.; Kain, J. Process of developing text messages on healthy eating and physical activity for Chilean mothers with overweight or obese preschool children to be delivered via WhatsApp. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antle, B.J.; Mills, W.; Steele, C.; Kalnins, I.; Rossen, B. An exploratory study of parents’ approaches to health promotion in families of adolescents with physical disabilities. Child: Care Health Dev. 2008, 34, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handler, L.; Tennant, E.M.; Faulkner, G.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E. Perceptions of Inclusivity: The Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Youth. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2019, 36, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaarsma, E.A.; Haslett, D.; Smith, B. Improving Communication of Information About Physical Activity Opportunities for People with Disabilities. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2019, 36, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natkunam, T.; Tristani, L.; Peers, D.; Fraser-Thomas, J.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Bassett-Gunter, R. Using a think-aloud methodology to understand online physical activity information search experiences and preferences of parents of children and youth with disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2020, 33, 1478–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tristani, L.K.; Bassett-Gunter, R.; Tanna, S. Evaluating Internet-Based Information on Physical Activity for Children and Youth with Physical Disabilities. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2017, 34, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, K.M.; Updegraff, J.A. Health Message Framing Effects on Attitudes, Intentions, and Behavior: A Meta-analytic Review. Ann. Behav. Med. 2012, 43, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.-K.; Cheng, S.-T.; Fung, H.H. Effects of Message Framing on Self-Report and Accelerometer-Assessed Physical Activity Across Age and Gender Groups. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2014, 36, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainforth, H.L.; Cao, W.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E. Message Framing and Parents’ Intentions to have their Children Vaccinated against HPV. Public Health Nurs. 2012, 29, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, V.; Clark, M.; Berry, T.; Holt, N.L.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E. A qualitative examination of the perceptions of parents on the Canadian Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines for the early years. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Spence, J.C.; Berry, T.R.; Deshpande, S.; Faulkner, G.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; O’Reilly, N.; Tremblay, M.S. Understanding action control of parental support behavior for child physical activity. Health Psychol. 2016, 35, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jetha, A.; Faulkner, G.; Gorczynski, P.; Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K.; Ginis, K.A.M. Physical activity and individuals with spinal cord injury: Accuracy and quality of information on the Internet. Disabil. Health J. 2011, 4, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassett-Gunter, R.; Tanna, S.; Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K.; Rhodes, R.E.; Leo, J. Understanding Parent Support for Physical Activity among Parents of Children and Youth with Disabilities: A Behaviour Change Theory Perspective. Eur. J. Adapt. Phys. Act. 2020, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.M.; Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K.P.; Ginis, K.A.M.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Bassett-Gunter, R.L. Examining the relationship between parent physical activity support behaviour and physical activity among children and youth with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2020, 24, 1783–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.; Kim, S.-Y.; Lee, E. Parents’ Beliefs and Intentions Toward Supporting Physical Activity Participation for Their Children with Disabilities. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2015, 32, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, A.; Bowles, H.R.; Huhman, M.; Heitzler, C.D.; Owen, N.; Smith, B.; Reger-Nash, B. Testing a Hierarchy-of-Effects Model: Pathways from Awareness to Outcomes in the VERB™ Campaign 2002–2003. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 34, S249–S256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhman, M.; Kelly, R.P.; Edgar, T. Social Marketing as a Framework for Youth Physical Activity Initiatives: A 10-Year Retrospective on the Legacy of CDC’s VERB Campaign. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2017, 6, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lankford, T.; Wallace, J.; Brown, D.; Soares, J.; Epping, J.N.; Fridinger, F. Analysis of Physical Activity Mass Media Campaign Design. J. Phys. Act. Health 2014, 11, 1065–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Deshpande, S.; Bonates, T. Effectiveness of Social Marketing Interventions to Promote Physical Activity Among Adults: A Systematic Review. J. Phys. Act. Health 2016, 13, 1263–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grier, S.; Bryant, C.A. Social Marketing in Public Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2005, 26, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buller, D.B. Diffusion and Dissemination of Physical Activity Recommendations and Programs to World Populations. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2006, 31, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noar, S.M.; Benac, C.N.; Harris, M.S. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 133, 673–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, W.D.; Hastings, G. (Eds.) Public Health Branding: Applying Marketing for Social Change; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Price, S.M.; Potter, L.D.; Das, B.; Wang, Y.-C.L.; Huhman, M. Exploring the Influence of the VERB™ Brand Using a Brand Equity Framework. Soc. Mark. Q. 2009, 15, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letts, L.; Ginis, K.M.; Faulkner, G.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Gorczynski, P. Preferred methods and messengers for delivering physical activity information to people with spinal cord injury: A focus group study. Rehabil. Psychol. 2011, 56, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brawley, L.R.; Latimer, A.E. Physical activity guides for Canadians: Messaging strategies, realistic expectations for change, and evaluation. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2007, 32, S170–S184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.D.; Meischke, H. A Comprehensive Model of Cancer-Related Information Seeking Applied to Magazines. Hum. Commun. Res. 1993, 19, 343–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Term | Working Definition |

|---|---|

| Physical Activity (PA) | Any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure and results in increased heart rate and breathing was used to describe both structured PA such as sports and programs, as well as leisure time unstructured PA such playing with friends, dancing, or walking. Active transportation was also included. Types of “play” were included in the review as long as they were specified as physical or active play. |

| Parent | Biological or legal guardian and/or caregiver. |

| Child | Anyone up to and including age 24. |

| Disability | Activity limitation or participation restrictions caused by physical or cognitive impairment. |

| Messages and information | All information or knowledge about PA to be conveyed to a message recipient. All forms of information and messages were allowable and included (e.g., digital, print, radio). |

| Dissemination | Distribution of messages and information to a target audience via purposeful channels and strategies. All forms of dissemination were allowable and included (e.g., social media campaigns, mass media messaging/commercials, posting guidelines on websites, or communications with a practitioner). |

| Theme | Subtheme | Articles Identified | Main Relevant Findings | Recommendation for PA Message Development |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Message persuasion | (a) Message framing | [30,33] | Gain-framed PA messages targeting parents were more effective in promoting message engagement, believability, positive attitudes, and overall favourability compared to loss-framed messages [33]. Gain- and loss-framed PA messages were equally effective [30]. | Messages targeting parents should be gain-framed to promote motivation and encouragement to provide support for PA. |

| (2) Messages that consider barriers to parent support for PA | (a) Common barriers to parent support for PA | [34,35,36,37] | Common barriers to providing parent support for PA include time [34,35,36,37], safety concerns [35], money [34,35] weather [35,36,37], lack of facilities [35], and parents’ motivation to provide support for PA [37]. | Messages targeting parents should address common barriers they experience (e.g., time, money, safety, and weather). Such messages can boost parents’ perceived control over providing support for PA by enhancing their self-efficacy. |

| (b) Information regarding PA guidelines | [34,37,38] | Many parents are unaware of PA guidelines, or exhibit low knowledge of PA guidelines [38]. To enhance understanding, parents desire clarity around definitions of PA [38], classifications of PA intensities (e.g., light, moderate, vigorous) [34] and examples of different types of PA to alleviate some confusion surrounding PA guidelines [37]. | Messages targeting parents should provide parents with practical information regarding PA guidelines. For example, providing parents with examples of different types of PA (e.g., light, moderate and vigorous), providing clear definitions of what qualifies as PA, and strategies to assess their child’s PA. | |

| (c) Guilt and stress | [34,37,38,39] | Persuasive PA messages can evoke feelings of stress among parents [38] as PA guidelines are perceived as something else to worry about by parents [34,37]. Parents were not motivated by messages that evoked feelings of guilt and rather these messages were negatively associated with parents’ perceived behavioural control and intentions to provide support for PA [39]. | Messages targeting parents should remain supportive, positive and pragmatic in order to provide parents with feelings of motivation and achievement rather than promoting feelings of guilt and stress. | |

| (3) Messages that target parents’ attitudes | (a) Attitudes toward child PA | [14,15,35,36,38,40,41,42] | The existing research suggests that parents generally hold positive attitudes and perceptions toward child PA [14,35,36,38]. Parents who felt motivated after viewing a PA message had more positive attitudes toward child PA [40]. Positive effects of messages on parents’ attitudes toward child PA have been observed [15,42]. A common disconnect between parents’ attitudes toward child PA in general and their own child’s PA [14,38,41] was identified. | Messages targeting parents should focus on the presenting the benefits of child PA and present strategies to help increase their own child’s PA. Such messages may serve as a booster to parent support for PA. |

| (b) Attitudes toward parent support for PA | [42,43] | The current literature suggests that targeting parents’ affective attitudes toward support for PA can be an effective strategy to motivate parents to provide support [43]. PA campaigns targeting parents have had success in motivating parents to provide support by providing them with information about the benefits of providing their child with support for PA [42]. | Messages targeting parents should target parents affective and instrumental attitudes toward parent support for PA and focus on presenting the benefits of providing support for PA. |

| Theme | Subtheme | Articles Identified | Main Relevant Findings | Recommendation for PA Message and Information Dissemination |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Dissemination to enhance cognitive processing | (a) Awareness | [10,42,44] | Message awareness is positively associated with favourable attitudes toward child PA among parents [42]. Compared to parents with low PA message awareness, parents with greater awareness were more likely to believe that PA offered benefits to their children [44]. Parents with greater PA campaign message awareness were more likely to believe their children needed to engage in more PA, had stronger intentions to provide parent support for PA, and exhibited greater support for PA compared to parents with low campaign awareness [10]. It is important to garner awareness to promote changes in beliefs and intentions toward child PA and parent support for PA [10,42,44]. | Messages targeting parents should focus on dissemination strategies such as repeated exposure to promote campaign and message awareness which can positively impact pre-intentional factors. |

| (b) Recall | [42,44,45,46] | PA message recall among parents is positively associated with attitudes, beliefs, and support for PA behaviours [42], as well as greater knowledge regarding child PA and increased family PA [45]. However, PA message recall is generally low among parents [44] unless it is prompted [46]. | Messages targeting parents should focus on dissemination strategies that promote recall such as repeated exposure. Such strategies have the potential to positively impact pre-intentional factors. | |

| (2) Social marketing strategies to enhance dissemination | (a) Marketing strategies | [47,48,49] | The success of a PA campaign in the United States called VERB is thought to be the result of the marketing professionals who developed the campaign based on extensive consumer research [47,48]. The VERB campaign was branded as cool and fun, and ensured that the PA messages reflected core attributes of the brand [48]. The VERB campaign employed social marketing tactics such as developing a brand affinity (i.e., messaging that aligned with the parents’ values) [49], using paid media advertising, contests and community-based events, as well as collaborating with popular celebrities or athletes [49]. | Messages targeting parents should utilize marketing strategies for optimal dissemination such as audience research, channel placement and outcome evaluation. |

| (b) Tailoring dissemin-ation for subgroups of parents | [48,49] | The VERB campaign successfully targeted parents of Asian, Indian, Latino, and African American backgrounds by tailoring PA messages to reflect dissemination needs and preferences of various subgroups (e.g., delivered in various languages, disseminated through preferred radio television stations [48,49]). | Messages targeting parents should tailor messages to subgroups of parents to enhance message dissemination to improve the uptake of PA messages. | |

| (c) Brand equity | [15,47] | To enhance brand equity, the VERB campaign’s use of popular television characters and airing messages during popular television times for parents and children [47]. Within this campaign, brand equity increased steadily over a two-year period [47]. Brand equity also increased among parents after six months of PA message exposure and parents who reported higher brand equity also reported higher levels of parent support for PA [15]. | Messages targeting parents should utilize strategies to enhance brand equity (e.g., celebrity endorsement or credible messengers). Higher brand equity can lead to increases in parent support for PA or factors related to parent support for PA. | |

| (3) Messages that target the dissemination preferences and suggestions of parents | (a) Preferred Message Dissemin-ation Approaches | [34,50,51,52,53,54,55] | Multi-platform approaches were highlighted in the current literature [34,50,52]. Parents preferred both digital and traditional forms of dissemination [34,53]. One study suggested the use of a mass media approach to reach a large population [53]. Two studies found text messages are both feasible and efficacious for disseminating information to parents [54,55]. Unique forms of PA message and information dissemination through storybooks or “parent nights” within the community may be novel and creative methods to motivate parent support for PA [50,51]. | Messages targeting parents should utilize dissemination strategies that parents prefer. Such dissemination strategies should utilize a combination of both digital and traditional forms. Unique forms of dissemination can be used (e.g., text messages or parent nights) but in combination with other dissemination strategies. |

| Theme | Subtheme | Articles Identified | Main Relevant Findings | Recommendation for PA Message and Information Development |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Common Barriers to Parent Support for PA Among Parents of CWD | (a) Lack of information | [17,56,57,58,59,60] | One content analyses of PA websites for CWD found that less than 25% of the websites provided accurate information or appropriate knowledge-based information (e.g., PA recommendations, definitions of PA, and barriers) [60]. A lack of access to accurate and disability-specific PA information can create feelings of frustration among parents of CWD [17,56,57,58,59] which can negatively influence motivation to provide support for PA. For example, mothers assessing the Canadian movement guidelines described them as “incompatible with the abilities, experiences, and needs of CWD” [57]. Parents of CWD have also expressed concern regarding the lack of clarity around the use of terms such as “inclusive” or “accessible” with PA messages [17,59]. Parents have expressed a need for inclusive images and modifications for certain behaviours within PA messages [57]. | Messages targeting parents of CWD should focus on addressing the lack of disability specific information available to parents. Such messages can include information regarding clear and concise PA definitions and types of programming available, details regarding accessibility, inclusivity and support available, information regarding safety, and ideas for facilitating PA at home. |

| (b) PA Barriers salient to parents of CWD | [17,56,57,58,59] | Commonly reported barriers included high costs of program participation [57], transportation coordination [57], lack of disability-specific PA opportunities [58], lack of targeted PA Information [17,58,59] and social inclusion [56]. The literature discussed the extraordinary efforts that are required for parents of CWD to support their child’s PA while overcoming barriers and balancing safety concerns with independence [17,56,59]. Heightened concerns regarding their children’s safety during PA participation is a prevalent issue for parents of CWD [56,59]. Parents have directly expressed a desire for information regarding the safety of PA opportunities and specific guidelines for children with varying disabilities [17,56,57]. | Messages targeting parents of CWD should address common barriers that they experience (e.g., transportation coordination, cost of programs, safety, and social inclusion). Some suggestions include providing information regarding program staff, using inclusive images and providing safety information. Such messages can help parents feel prepared to overcome certain barriers they experience. | |

| (2) Messages that target psychosocial antecedents of parent support for PA among parents of CWD | (a) Theoretical predictors of behaviour change | [60] | Literature highlights a lack of theory or evidence-based information with the PA website content targeting CWD [60]. Messages targeting self-efficacy were the most common source of messaging targeting a theoretical predictor of behaviour change, while less than 10% of web-content included messages targeting self-regulation, self-monitoring, and planning [60]. | Messages targeting parents of CWD should target theory-based constructs such as pre-intentional factors (e.g., attitudes, perceived behavioural control and subjective norms) and post-intentional factors (e.g., behavioural regulation and planning) to enhance message effectiveness. Messages should facilitate planning and self-regulation regarding support for PA as such information is significantly lacking for parents of CWD specifically. |

| Theme | Subtheme | Articles Identified | Main Relevant Findings | Recommendation for PA Message and Information Dissemination |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Dissemination Preferences and Suggestions of Parents of CWD | (a) Preferred dissemination approaches | [17,58,59] | Parents of CWD can benefit from a multi-platform approach to message and information dissemination [17,58]. Parents of CWD expressed desire for information that is easily accessible and disseminated through credible and reliable sources [17,58,59]. Parents desire a “central hub” for finding targeted PA messages [17]. Many parents of CWD seek PA information and learn from other parents of CWD [17,58]. As such, communication spaces such as blogs, chat rooms, and message boards are of value to support parents in finding and sharing PA information [17]. | Messages targeting parents should utilize dissemination strategies that parents of CWD prefer. Some suggestions include a “central hub” for information, information disseminated by credible sources, and a multi-platform approach. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Larocca, V.; Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K.P.; Tomasone, J.R.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Bassett-Gunter, R.L. Developing and Disseminating Physical Activity Messages Targeting Parents: A Systematic Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7046. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18137046

Larocca V, Arbour-Nicitopoulos KP, Tomasone JR, Latimer-Cheung AE, Bassett-Gunter RL. Developing and Disseminating Physical Activity Messages Targeting Parents: A Systematic Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(13):7046. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18137046

Chicago/Turabian StyleLarocca, Victoria, Kelly P. Arbour-Nicitopoulos, Jennifer R. Tomasone, Amy E. Latimer-Cheung, and Rebecca L. Bassett-Gunter. 2021. "Developing and Disseminating Physical Activity Messages Targeting Parents: A Systematic Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 13: 7046. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18137046

APA StyleLarocca, V., Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K. P., Tomasone, J. R., Latimer-Cheung, A. E., & Bassett-Gunter, R. L. (2021). Developing and Disseminating Physical Activity Messages Targeting Parents: A Systematic Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(13), 7046. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18137046