Nature-Based Rehabilitation for Patients with Long-Standing Stress-Related Mental Disorders: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis of Patients’ Experiences

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- Inclusion criteria:

- Population: Patients with long-standing (>6 months) stress-related mental disorders without known ongoing drug abuse

- Exposure: Multidisciplinary, group-based NBR

- Outcome: Experiences of participating in a NBR program

- Study design: Qualitative studies

- Languages: English, Danish, Norwegian, Swedish

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), known drug abuse

2.3. Data Sources

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Critical Appraisal and Confidence in Evidence

2.6. Data Extraction and Management

2.7. Data Synthesis and Analysis

3. Results

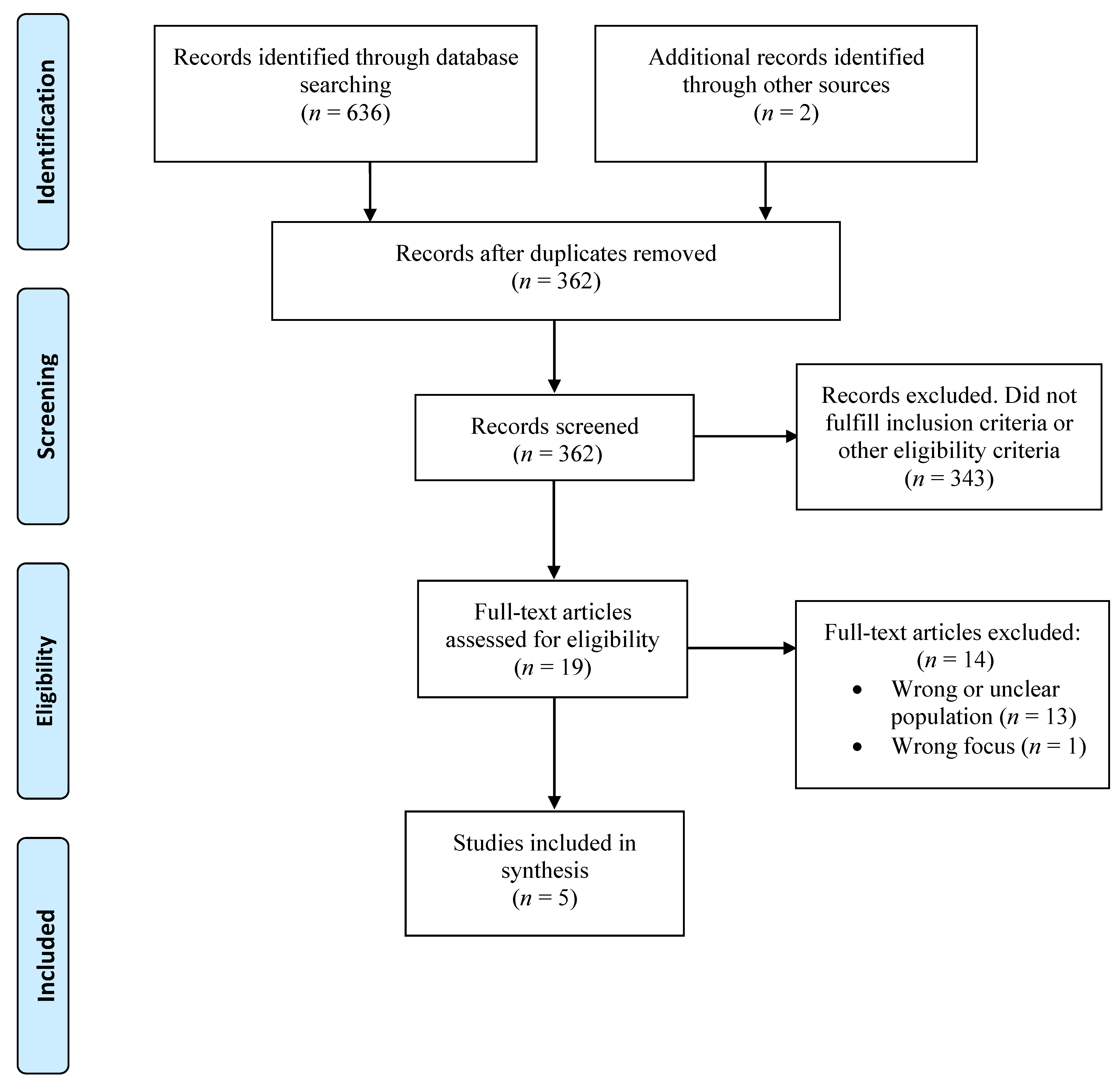

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Study Quality and Confidence in Evidence

3.4. Synthesis

3.5. Analytical Themes

3.5.1. Instilling Calm and Joy

3.5.2. Needs Being Met

3.5.3. Gaining New Insights

3.5.4. Personal Growth

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salomon, J.A.; Wang, H.; Freeman, M.K.; Vos, T.; Flaxman, A.D.; Lopez, A.D. Healthy life expectancy for 187 countries, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden Disease Study 2010. Lancet (Lond. Engl.) 2012, 380, 2144–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, T.; Flaxman, A.D.; Naghavi, M.; Lozano, R.; Michaud, C.; Ezzati, M. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet (Lond. Engl.) 2012, 380, 2163–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. Burnout in the Workplace: A Review of Data and Policy Responses in the EU; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, M.; Glozier, N.; Holland Elliott, K. Long term sickness absence. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2005, 330, 802–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefansson, C.G. Chapter 5.5: Major public health problems—Mental ill-health. Scand. J. Public Health Suppl. 2006, 67, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedish Social Insurance Agency. Socialförsäkringsrapport 2017:13. Sjukfrånvarons Utveckling 2017 [Internet]; Swedish Social Insurance Agency: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017. Available online: https://www.forsakringskassan.se/wps/wcm/connect/1596d32b-7ff7-4811-8215-d90cb9c2f38d/sjukfranvarons-utveckling-2017-socialforsakringsrapport-2017-13.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID= (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Sahlin, E.; Ahlborg, G., Jr.; Tenenbaum, A.; Grahn, P. Using nature-based rehabilitation to restart a stalled process of rehabilitation in individuals with stress-related mental illness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 1928–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahn, P.; Stigsdotter, U.K. The relation between perceived sensory dimensions of urban green space and stress restoration. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 94, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corazon, S.S.; Sidenius, U.; Poulsen, D.V.; Gramkow, M.C.; Stigsdotter, U.K. Psycho-Physiological Stress Recovery in Outdoor Nature-Based Interventions: A Systematic Review of the Past Eight Years of Research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ahlborg, G., Jr.; Bergenheim, A.; Eriksson, M.; Jivegård, L.; Sundell, G.; Svanberg, T. Nature-Based Rehabilitation for Patients with Longstanding Stress-Related Disorders—An Updated Report. Regional Activity-Based HTA; Report No. 2020–112; Region Västra Götaland, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, HTA-Centrum: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2020; Available online: https://alfresco-offentlig.vgregion.se/alfresco/service/vgr/storage/node/content/workspace/SpacesStore/20e62995-a89c-47d7-8b64-82746284f34e/HTA-rapport%20Gr%c3%b6n%20Rehab%20inkl%20app%20200221.pdf?a=false&guest=true (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Lewin, S.; Booth, A.; Glenton, C.; Munthe-Kaas, H.; Rashidian, A.; Wainwright, M. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: Introduction to the series. Implement. Sci. IS 2018, 13 (Suppl. 1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Flemming, K.; McInnes, E.; Oliver, S.; Craig, J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2012, 12, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Canadian Health Libraries Association. Qualitative Research 2021. Available online: https://extranet.santecom.qc.ca/wiki/!biblio3s/doku.php?id=concepts:recherche-qualitative (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Bedömning av Studier med Kvalitativ Metodik. SBU Statens beredning för Medicnisk och Social Utvärdering; 2014. Available online: https://www.sbu.se/globalassets/ebm/bedomning_studier_kvalitativ_metodik.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Lewin, S.; Glenton, C.; Munthe-Kaas, H.; Carlsen, B.; Colvin, C.J.; Gülmezoglu, M. Using qualitative evidence in decision making for health and social interventions: An approach to assess confidence in findings from qualitative evidence syntheses (GRADE-CERQual). PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Adevi, A.A.; Lieberg, M. Stress rehabilitation through garden therapy. Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 11, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palsdottir, A.M.; Grahn, P.; Persson, D. Changes in experienced value of everyday occupations after nature-based vocational rehabilitation. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2014, 21, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palsdottir, A.M.; Persson, D.; Persson, B.; Grahn, P. The journey of recovery and empowerment embraced by nature—Clients’ perspectives on nature-based rehabilitation in relation to the role of the natural environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 7094–7115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sahlin, E.; Vega Matuszczyk, J.; Ahlborg, G.; Grahn, P., Jr. How do Participants in Nature-Based Therapy Experience and Evaluate Their Rehabilitation? J. Ther. Hortic. 2012, 22, 8–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sidenius, U.; Stigsdotter, U.K.; Varning Poulsen, D.; Bondas, T. I look at my own forest and fields in a different way: The lived experience of nature-based therapy in a therapy garden when suffering from stress-related illness. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2017, 12, 1324700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Picton, C.; Fernandez, R.; Moxham, L.; Patterson, C.F. Experiences of outdoor nature-based therapeutic recreation programs for persons with a mental illness: A qualitative systematic review. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 1820–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annerstedt, M.; Währborg, P. Nature-assisted therapy: Systematic review of controlled and observational studies. Scand. J. Public Health 2011, 39, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamioka, H.; Tsutani, K.; Yamada, M.; Park, H.; Okuizumi, H.; Honda, T. Effectiveness of horticultural therapy: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Complement. Ther. Med. 2014, 22, 930–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, M.; Morgan, J. Mental health recovery and nature: How social and personal dynamics are important. Ecopsychology 2018, 10, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, T.; Westerberg, Y.; Jonsson, H. Experiences of women with stress-related ill health in a therapeutic gardening program. Can. J. Occup. Ther. Rev. Can. D’ergotherapie 2011, 78, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Glise, K.; Ahlborg, G., Jr.; Jonsdottir, I.H. Course of mental symptoms in patients with stress-related exhaustion: Does sex or age make a difference? BMC Psychiatry 2012, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Author, Year, Country | Aim | Setting | Length of NBR | Patients (n) | Mean Age (years) | Study Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adevi, 2013, Sweden [18] | To explore the impact of garden therapy on stress rehabilitation, with special focus on the role of nature. | The health garden on the campus of the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences in Alnarp, Sweden. | Not stated | 5 (4 women, 1 man) | Range 25–60 | Patients with exhaustion disorder |

| Palsdottir, 2014a, Sweden [19] | To describe and assess changes in the participants’ experienced value of everyday occupations after NBR. | The health garden on the campus of the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences in Alnarp, Sweden. | 12 weeks | 21 (19 women, 2 men) | 47 | Patients with adjustment disorder, reaction to severe stress, or depression |

| Palsdottir, 2014b, Sweden [20] | To explore and illustrate how participants with stress-related mental disorders participating in NBR experience and describe their rehabilitation process. | The health garden on the campus of the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences in Alnarp, Sweden. | 12 weeks | 43 (35 women, 8 men) | 46 | Patients on long-term sick leave for adjustment disorder, reaction to severe stress, or depression |

| Sahlin, 2012, Sweden [21] | To explore how participants in a NBR program experience, explain, and evaluate their rehabilitation. | The Botanical Garden in Gothenburg, Sweden. | 12–44 weeks | 11 (8 women, 3 men) | 43 | Patients employed within administration and healthcare with Exhaustion disorder and/or depression and anxiety |

| Sidenius, 2017, Denmark [22] | The aim of this study is to describe the phenomenon of participants’ lived experiences of the NBT in Nacadia during the course of a 10-week NBT program. | The therapy garden Nacadia, Copenhagen, Denmark. | 10 weeks | 14 (Women/men not reported) | Not reported | Patients with inability to work for at least 3 months with adjustment disorder and/or reaction to severe stress |

| Study | Methods of Data Collection | Methods of Data Analysis | Assessment of Methodological Quality (Based on the sbu Assessment Tool for Qualitative Studies) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aim Well Defined | Sample Relevant, Selection and Context Well Described, Relevant Ethical Considerations | Researcher-Participant Relation Well Described | Data Collection Well Described and Relevant | Data Saturation | Researcher Pre-Understanding | Data Analysis Well Described | Findings Logical, Intelligible, Well Described | Findings Related to Theoretical Frame of Reference | |||

| Adevi 2013 [18] | Semi-structured interviews 0.5 to 1.5 years after the intervention | Grounded theory | Yes | Sample relevant but potentially biased; ethical considerations missing | No | Yes | Unclear | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Overall assessment: low-to-moderate | Limitations: Potential risk of bias in selection strategy (participants handpicked by garden manager), ethical considerations missing, preunderstanding not described | ||||||||||

| Palsdottir 2014a [19] | Semi-structured interviews 12 weeks after the intervention | Qualitative content analysis | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Overall assessment: moderate | Limitations: No citations, interviews not recorded, preunderstanding not described/handled | ||||||||||

| Palsdottir 2014b [20] | Semi-structured interviews within one month after program | Interpretative phenomenological analysis | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | Yes/unclear | Yes | |

| Overall methodology assessment: moderate-to-high | Limitations: Appropriateness of analysis method unclear | ||||||||||

| Sahlin 2012 [21] | Semi-structured interviews | Interpretative phenomenological analysis | Yes | Yes/ Ethical considerations missing | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes/no | Yes |

| Overall methodology assessment: moderate | Limitations: Ethical considerations missing, sample not clearly described, findings not clearly described | ||||||||||

| Sidenius 2017 [22] | Semi-structured interviews, avg. 20 min, in 2nd, 5th, 9th week of program | Reflective life world research | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Overall methodology assessment: high | Limitations: Lack of description of sample characteristics and preunderstanding in relation to data collection | ||||||||||

| Summary of Review Finding | Number of Studies Contributing to the Review Finding/Total Studies Included in the Review | CERQual Assessment of Confidence in the Evidence | Explanation of CERQual Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instilling calm and joy | |||

| Patients described how nature’s peace and quiet had a calming impact on their state of mind. | 5/5 [18,19,20,21,22] | Moderate confidence | Minor concerns about adequacy as the data come from a small number of studies. The studies were of moderate to high quality. |

| Patients expressed that NBR made them feel joy in daily tasks. | 4/5 [18,19,20,22] | Moderate confidence | Minor concerns about adequacy as the data come from a small number of studies. The studies were of moderate to high quality. |

| Patients experienced that NBR created a sense of belonging to a greater whole and helped patients to find meaning and values. | 4/5 [18,20,21,22] | Moderate confidence | Minor concerns about adequacy as the data come from a small number of studies. The studies were of moderate to high quality. |

| Patients described themselves as becoming one with nature during NBR, enabling them to get closer to their feelings. | 3/5 [18,20,21] | Low confidence | Moderate concerns about adequacy as the data come from a very small number of studies and the studies were of moderate to high quality. |

| Patients described how sensory experiences in the garden helped them to be in the present. | 3/5 [20,21,22] | Low confidence | Moderate concerns about adequacy as the data come from a very small number of studies. The studies were of moderate to high quality. |

| Needs being met | |||

| Patients experienced that the garden gave a sense of safety and security. | 4/5 [18,20,21,22] | Moderate confidence | Minor concerns about adequacy as the data come from a small number of studies. The studies were of moderate to high quality. |

| Patients experienced that the therapeutic garden met their needs. | 3/5 [18,20,22] | Low confidence | Moderate concerns about adequacy as the data come from a very small number of studies, and the finding was seen in three of the five studies of which only one provided sufficiently rich data. The studies were of high quality. |

| The garden was perceived as an undemanding, tolerant, and permissive setting. | 4/5 [18,20,21,22] | Moderate confidence | Minor concerns about adequacy as the data come from a small number of studies. The studies were of moderate to high quality. |

| Patients described that NBR helped them slow down and adjust to nature’s slower pace. | 4/5 [18,19,20,21,22] | Moderate confidence | Minor concerns about adequacy as the data come from a small number of studies. The studies were of moderate to high quality. |

| Nature was experienced as a restorative environment that facilitated recovery. | 5/5 [18,19,20,21,22] | Moderate confidence | Minor concerns about adequacy as the data come from a small number of studies. The studies were of moderate to high quality. |

| Gaining new insights | |||

| Patients described gaining self-acceptance through kinship with nature, which helped them come to terms with being ill. | 3/5 [18,21,22] | Low confidence | Moderate concerns about adequacy as the data come from a very small number of studies. The studies were of moderate to high quality. |

| Patients experienced that NBR increased their awareness of own needs and destructive patterns in daily life. | 2/5 [19,22] | Low confidence | Moderate concerns about adequacy as the data come from a very small number of studies. The studies were of high quality. |

| Nature was perceived as a source of creativity and energy, making room for new ideas and affecting inner strength. | 5/5 [18,19,20,21,22] | Moderate confidence | Minor concerns about adequacy as the data come from a small number of studies. The studies were of moderate to high quality. |

| Personal growth | |||

| Patients’ experiences in nature and the garden helped them see things differently and develop new perspectives. | 3/5 [18,21,22] | Low confidence | Moderate concerns about adequacy as the data come from a very small number of studies. The studies were of moderate to high quality. |

| The patients developed new approaches to tasks in their daily life. | 3/5 [19,21,22] | Moderate confidence | Minor concerns about adequacy as the data come from a small number of studies. The studies were of moderate to high quality. |

| NBR was perceived as increasing empowerment, which enabled the patients to move forward. | 4/5 [19,20,21,22] | Moderate confidence | Minor concerns about adequacy as the data come from a small number of studies. The studies were of moderate to high quality. |

| Analytical Themes | Descriptive Themes |

|---|---|

| Instilling calm and joy | Calming impact of nature |

| Joy in daily tasks | |

| Finding meaning and sense of belonging | |

| Being one with nature | |

| Being in the present | |

| Needs being met | Garden giving a sense of safety and security |

| Garden meeting needs | |

| Garden as an undemanding and permissive setting | |

| Adjusting to nature’s slower pace | |

| Nature as a restorative environment | |

| Gaining new insights | Gaining self-acceptance |

| Increased self-awareness | |

| Insights of nature as source of creativity and energy | |

| Personal growth | Developing new perspectives |

| Developing new approaches | |

| Moving forward through empowerment |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bergenheim, A.; Ahlborg, G., Jr.; Bernhardsson, S. Nature-Based Rehabilitation for Patients with Long-Standing Stress-Related Mental Disorders: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis of Patients’ Experiences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6897. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136897

Bergenheim A, Ahlborg G Jr., Bernhardsson S. Nature-Based Rehabilitation for Patients with Long-Standing Stress-Related Mental Disorders: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis of Patients’ Experiences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(13):6897. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136897

Chicago/Turabian StyleBergenheim, Anna, Gunnar Ahlborg, Jr., and Susanne Bernhardsson. 2021. "Nature-Based Rehabilitation for Patients with Long-Standing Stress-Related Mental Disorders: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis of Patients’ Experiences" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 13: 6897. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136897

APA StyleBergenheim, A., Ahlborg, G., Jr., & Bernhardsson, S. (2021). Nature-Based Rehabilitation for Patients with Long-Standing Stress-Related Mental Disorders: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis of Patients’ Experiences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(13), 6897. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136897