Validation and Test of Measurement Invariance of the Adapted Health Consciousness Scale (HCS-G)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Adaption of the HCS-G and Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Study Variables

2.3.1. Health Literacy

2.3.2. Impulsivity

2.3.3. Personality Traits

2.3.4. Further Constructs

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Sample

3.2. Item Statistics

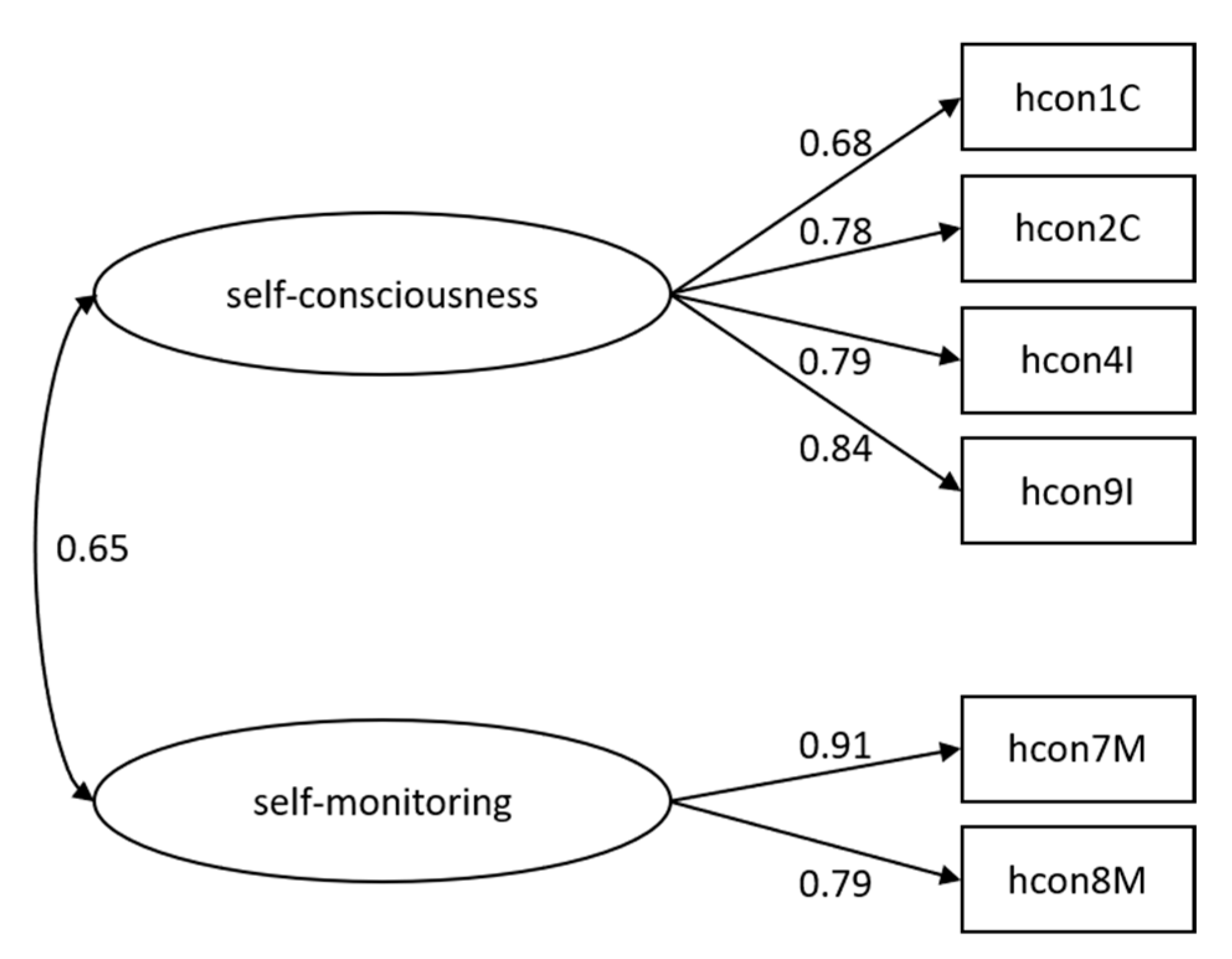

3.3. Confirmatory Factor Analyses

3.4. Validation Analyses

3.4.1. Health Consciousness and Sociodemographic Variables

3.4.2. Validation of Health Consciousness

3.5. Measurement Invariance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Firth, J.; Solmi, M.; Wootton, R.E.; Vancampfort, D.; Schuch, F.B.; Hoare, E.; Gilbody, S.; Torous, J.; Teasdale, S.B.; Jackson, S.E. A Meta-Review of “Lifestyle Psychiatry”: The Role of Exercise, Smoking, Diet and Sleep in the Prevention and Treatment of Mental Disorders. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 360–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uusitupa, M.; Khan, T.A.; Viguiliouk, E.; Kahleova, H.; Rivellese, A.A.; Hermansen, K.; Pfeiffer, A.; Thanopoulou, A.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Schwab, U.; et al. Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes by Lifestyle Changes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghajanpour, M.; Nazer, M.R.; Obeidavi, Z.; Akbari, M.; Ezati, P.; Kor, M. Functional Foods and Their Role in Cancer Prevention and Health Promotion: A Comprehensive Review. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2017, 7, 740–769. [Google Scholar]

- Aubrey, V.; Hon, Y.; Shaw, C.; Burden, S. Healthy Eating Interventions in Adults Living with and beyond Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 32, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Lee, I.-M.; Ajani, U.; Cole, S.R.; Buring, J.E.; Manson, J.E. Intake of Vegetables Rich in Carotenoids and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in Men: The Physicians’ Health Study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2001, 30, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin, J.A.; Colditz, G.A. A Meta-Analysis of Physical Activity in the Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1990, 132, 612–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prentice, R.L.; Willett, W.C.; Greenwald, P.; Alberts, D.; Bernstein, L.; Boyd, N.F.; Byers, T.; Clinton, S.K.; Fraser, G.; Freedman, L.; et al. Nutrition and Physical Activity and Chronic Disease Prevention: Research Strategies and Recommendations. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2004, 96, 1276–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Wannamethee, S.G.; Shaper, A.G. Physical Activity in the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. Sports Med. 2001, 31, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Healthy Diet—Fact Sheet No. 394. Available online: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Roberts, J.A.; David, M.E. Improving Predictions of COVID-19 Preventive Behavior: Development of a Sequential Mediation Model. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e23218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarwar, F.; Panatik, S.A.; Sarwar, F. Psychology of Preventive Behavior for COVID-19 Outbreak. J. Res. Psychol. 2020, 2, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, S.J. Health Consciousness and Health Behavior: The Application of a New Health Consciousness Scale. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1990, 6, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, A.C.; Kraft, P. Does Socio-Economic Status and Health Consciousness Influence How Women Respond to Health Related Messages in Media? Health Educ. Res. 2006, 21, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayanti, R.K.; Burns, A.C. The Antecedents of Preventive Health Care Behavior: An Empirical Study. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1998, 26, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, R.B.; Schafer, E.; Bultena, G.; Hoiberg, E. Coping With a Health Threat: A Study of Food Safety1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 23, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snell, W.E.; Johnson, G.; Lloyd, P.J.; Hoover, M.W. The Health Orientation Scale: A Measure of Psychological Tendencies Associated with Health. Eur. J. Personal. 1991, 5, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffrey, S.C. Development of a Health Conception Scale. Res. Nurs. Health 1986, 9, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallston, B.S.; Wallston, K.A.; Kaplan, G.D.; Maides, S.A. Development and Validation of the Health Locus of Control (HLC) Scale. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1976, 44, 580–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, S.J. Consumer Attitudes Toward Health and Health Care: A Differential Perspective. J. Consum. Aff. 1988, 22, 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta-Bergman, M.J. Primary Sources of Health Information: Comparisons in the Domain of Health Attitudes, Health Cognitions, and Health Behaviors. Health Commun. 2004, 16, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, A. Health Behaviors, Self-Rated Health, and Health Consciousness Among Latinx in New York City. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2020, 23, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesanovic, E.; Kadic-Maglajlic, S.; Cicic, M. Insights into Health Consciousness in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 81, 570–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Zhao, Q.; Santibanez-Gonzalez, E.D. How Chinese Consumers’ Intentions for Purchasing Eco-Labeled Products Are Influenced by Psychological Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 17, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriwy, P.; Mecking, R.-A. Health and Environmental Consciousness, Costs of Behaviour and the Purchase of Organic Food: Purchase of Organic Food. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.H.; Im, J.; Jung, S.E.; Severt, K. Motivations behind Consumers’ Organic Menu Choices: The Role of Environmental Concern, Social Value, and Health Consciousness. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2019, 20, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, S.; Yu, Y. Consumer’s Intention to Purchase Green Furniture: Do Health Consciousness and Environmental Awareness Matter? Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 704, 135275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Yu, H.; Ploeger, A. Exploring Influential Factors Including COVID-19 on Green Food Purchase Intentions and the Intention–Behaviour Gap: A Qualitative Study among Consumers in a Chinese Context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoda, A.; Hayashi, H.; Sussman, D.; Nansai, K.; Fukuba, I.; Kawachi, I.; Kondo, N. Our Health, Our Planet: A Cross-Sectional Analysis on the Association between Health Consciousness and pro-Environmental Behavior among Health Professionals. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2020, 30, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenigstein, A.; Scheier, M.F.; Buss, A.H. Public and Private Self-Consciousness: Assessment and Theory. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1975, 43, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.W. Scale Development for Measuring Health Consciousness. In Research That Matters to the Practice, Proceedings of the 12th Annual International Public Relations Research Conference, Holiday Inn University of Miami, Colral Gables, FL, USA, 11–14 March 2009; Institute for Public Relations: Coral Gables, FL, USA, 2009; p. 212. [Google Scholar]

- Čvirik, M. Health Conscious Consumer Behaviour: The Impact of a Pandemic on the Case of Slovakia. Cent. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2020, 9, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ture, R.S.; Ganesh, M.P. Effect of Health Consciousness and Material Values on Environmental Belief and Pro-Environmental Behaviours. Int. Proc. Econ. Dev. Res. 2012, 43, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the Process of Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Self-Report Measures. Spine 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillemin, F.; Bombardier, C.; Beaton, D. Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Health-Related Quality of Life Measures: Literature Review and Proposed Guidelines. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1993, 46, 1417–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, R.J.; Lance, C.E. A Review and Synthesis of the Measurement Invariance Literature: Suggestions, Practices, and Recommendations for Organizational Research. Organ. Res. Methods 2000, 3, 4–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, L.T.; Fischer, R. Testing Measurement Invariance across Groups: Applications in Cross-Cultural Research. Int. J. Psychol. Res. 2010, 3, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogg, T.; Vo, P.T. Openness, Neuroticism, Conscientiousness, and Family Health and Aging Concerns Interact in the Prediction of Health-Related Internet Searches in a Representative U.S. Sample. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandrack, M.-A.; Grant, K.R.; Segall, A. Gender Differences in Health Related Behaviour: Some Unanswered Questions. Soc. Sci. Med. 1991, 32, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.K.; Chu, H.J.; Lee, M.K.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, N.; Lee, S.M. A Meta-Analysis of Gender Differences in Attitudes toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help. J. Am. Coll. Health 2010, 59, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arber, S.; Cooper, H. Gender Differences in Health in Later Life: The New Paradox? Soc. Sci. Med 1999, 48, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Carbonell, M.; Espejo, B.; Checa, I.; Fernández-Daza, M. Adaptation and Measurement Invariance by Gender of the Flourishing Scale in a Colombian Sample. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collison, K.L.; South, S.; Vize, C.E.; Miller, J.D.; Lynam, D.R. Exploring Gender Differences in Machiavellianism Using a Measurement Invariance Approach. J. Pers. Assess. 2021, 103, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechorro, P.; DeLisi, M.; Gonçalves, R.A.; Quintas, J.; Hugo Palma, V. The Brief Self-Control Scale and Its Refined Version among Incarcerated and Community Youths: Psychometrics and Measurement Invariance. Deviant Behav. 2021, 42, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouquette, A.; Falissard, B. Sample Size Requirements for the Internal Validation of Psychiatric Scales. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2011, 20, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyriazos, T.A. Applied Psychometrics: Sample Size and Sample Power Considerations in Factor Analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in General. Psychology 2018, 09, 2207–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röthlin, F.; Pelikan, J.; Ganahl, K. Die Gesundheitskompetenzder 15-Jährigen Jugendlichen in Österreich. Abschlussbericht der Österreichischen Gesundheitskompetenz Jugendstudie im Auftrag des Hauptverbandsder Österreichischen Sozialversicherungsträger (HVSV); Ludwig Boltzmann Gesellschaft GmbH: Wien, Austria, 2013; p. 93. [Google Scholar]

- Kovaleva, A.; Beierlein, C.; Kemper, C.J.; Rammstedt, B. Die Skala Impulsives-Verhalten-8 (I-8). Zs. Soz. Items Skalen ZIS 2014, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammstedt, B.; Kemper, C.J.; Klein, M.C.; Beierlein, C.; Kovaleva, A. Big Five Inventory (BFI-10). Zs. Soz. Items Skalen ZIS 2014. Available online: https://zis.gesis.org/skala/Rammstedt-Kemper-Klein-Beierlein-Kovaleva-Big-Five-Inventory-(BFI-10) (accessed on 18 August 2020). [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2020; Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/indicators/oxygen-consuming-substances-in-rivers/r-development-core-team-2006 (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R.; RStudio, PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lüdecke, D. SjPlot: Data Visualization for Statistics in Social Science. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=sjPlot (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, T.D.; Pornprasertmanit, S.; Schoemann, A.M.; Rosseel, Y. SemTools: Useful Tools for Structural Equation Modeling. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=semTools (accessed on 7 February 2021).

- Revelle, W. Psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- Harrell, F.E., Jr. Hmisc: Harrell Miscellaneous. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=Hmisc (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-H. Confirmatory Factor Analysis with Ordinal Data: Comparing Robust Maximum Likelihood and Diagonally Weighted Least Squares. Behav. Res. Methods 2016, 48, 936–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, P.-W.; Shiverdecker, L.K. Performance of Estimators for Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Ordinal Variables with Missing Data. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2020, 27, 584–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, D.M. Testing for Factorial Invariance in the Context of Construct Validation. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2010, 43, 121–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Schoot, R.; Lugtig, P.; Hox, J. A Checklist for Testing Measurement Invariance. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 9, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschfeld, G.; Von Brachel, R. Improving Multiple-Group Confirmatory Factor Analysis in R–A Tutorial in Measurement Invariance with Continuous and Ordinal Indicators. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2014, 19, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnick, D.L.; Bornstein, M.H. Measurement Invariance Conventions and Reporting: The State of the Art and Future Directions for Psychological Research. Dev. Rev. 2016, 41, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sass, D.A.; Schmitt, T.A.; Marsh, H.W. Evaluating Model Fit With Ordered Categorical Data Within a Measurement Invariance Framework: A Comparison of Estimators. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2014, 21, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D.A.; Kaniskan, B.; McCoach, D.B. The Performance of RMSEA in Models With Small Degrees of Freedom. Sociol. Methods Res. 2015, 44, 486–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, A.; Kadić-Maglajlić, S. The Mediating Role of Health Consciousness in the Relation Between Emotional Intelligence and Health Behaviors. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa, A.; Kadić-Maglajlić, S. The Role of Health Consciousness, Patient–Physician Trust, and Perceived Physician’s Emotional Appraisal on Medical Adherence. Health Educ. Behav. 2019, 46, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gam, H.J.; Yu, U.-J.; Yang, S. The Effects of Health Consciousness on Environmentally Sustainable Textile Furnishing Product Purchase. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2020, 49, 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Crotty, K. Low Health Literacy and Health Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, P.N.; Shetterly, S.M.; Clarke, C.L.; Bekelman, D.B.; Chan, P.S.; Allen, L.A.; Matlock, D.D.; Magid, D.J.; Masoudi, F.A. Health Literacy and Outcomes Among Patients With Heart Failure. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2011, 305, 1695–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillinger, D.; Grumbach, K.; Piette, J.; Wang, F.; Osmond, D.; Daher, C.; Palacios, J.; Diaz Sullivan, G.; Bindman, A.B. Association of Health Literacy With Diabetes Outcomes. JAMA 2002, 288, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarzer, R.; Luszczynska, A. How to Overcome Health-Compromising Behaviors. Eur. Psychol. 2008, 13, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, J.K.; Hermans, R.C.J.; Sleddens, E.F.C.; Vink, J.M.; Kremers, S.P.J.; Ruiter, E.L.M.; Fisher, J.O. How to Bridge the Intention-Behavior Gap in Food Parenting: Automatic Constructs and Underlying Techniques. Appetite 2018, 123, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faries, M.D. Why We Don’t “Just Do It”: Understanding the Intention-Behavior Gap in Lifestyle Medicine. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2016, 10, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güner, R.; Hasanoğlu, İ.; Aktaş, F. COVID-19: Prevention and Control Measures in Community. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 50, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weismüller, B.; Schweda, A.; Dörrie, N.; Musche, V.; Fink, M.; Kohler, H.; Skoda, E.-M.; Teufel, M.; Bäuerle, A. Different Correlates of COVID-19-Related Adherent and Dysfunctional Safety Behavior. Front. Public Health 2021, 8, 625664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, D.; Tolossa, T.; Tsegaye, R.; Teshome, W. The Knowledge and Practice towards COVID-19 Pandemic Prevention among Residents of Ethiopia. An Online Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0234585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| gender | female | 332 | 71% |

| male | 138 | 29% | |

| marital status | married or in partnership | 344 | 73% |

| single | 115 | 24% | |

| other | 11 | 2% | |

| educational level | university degree | 273 | 58% |

| completed vocational training | 91 | 19% | |

| maturity for university | 77 | 16% | |

| secondary school certificate | 29 | 6% | |

| subjective financial situation | very good or good | 300 | 64% |

| average | 114 | 24% | |

| bad or very bad | 56 | 12% | |

| residential area | big city above 100,000 residents | 244 | 52% |

| city above 20,000 residents | 88 | 19% | |

| town or village up to 20,000 residents | 138 | 29% |

| Item | Mean | SD | Median | Skew | Kurtosis | Response Distribution | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||||

| hcon1C | 3.88 | 0.89 | 4 | −0.93 | 0.72 | 1% | 9% | 12% | 56% | 22% |

| hcon2C | 3.89 | 0.88 | 4 | −0.89 | 0.65 | 1% | 9% | 12% | 56% | 22% |

| hcon3C | 4.07 | 0.8 | 4 | −1.22 | 2.25 | 1% | 6% | 6% | 60% | 27% |

| hcon4I | 3.71 | 0.97 | 4 | −0.74 | −0.02 | 2% | 13% | 15% | 52% | 18% |

| hcon5A | 4.1 | 0.72 | 4 | −1.06 | 2.42 | 0% | 4% | 7% | 63% | 26% |

| hcon6A | 4.19 | 0.67 | 4 | −0.84 | 1.71 | 0% | 3% | 6% | 61% | 30% |

| hcon7M | 3.23 | 1.01 | 3 | −0.23 | −0.79 | 3% | 24% | 26% | 39% | 8% |

| hcon8M | 3.56 | 0.91 | 4 | −0.61 | −0.14 | 1% | 14% | 22% | 52% | 11% |

| hcon9I | 3.75 | 0.92 | 4 | −0.62 | −0.25 | 0% | 13% | 16% | 51% | 19% |

| Model | Chi2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) single factor | 229.990 | 27 | 0.763 | 0.684 | 0.127 | 0.077 |

| (2) four-factor | 114.590 | 21 | 0.891 | 0.813 | 0.097 | 0.056 |

| (3) single factor (short) | 193.054 | 9 | 0.695 | 0.491 | 0.209 | 0.087 |

| (4) three-factor (short) | 34.200 | 6 | 0.953 | 0.883 | 0.100 | 0.035 |

| (5) two-factor (short) | 37.854 | 8 | 0.950 | 0.907 | 0.089 | 0.038 |

| HCS-G (sc) | HCS-G (sm) | Age | Marital Status | Educational Level | Financial Situation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCS-G (sm) | 0.55 *** | |||||

| age | 0.07 | 0.02 | ||||

| marital status | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.02 | |||

| educational level | −0.06 | −0.13 ** | −0.04 | −0.08 | ||

| financial situation | −0.05 | −0.08 | 0.12 ** | −0.12 ** | 0.22 *** | |

| residential area | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.13 ** | 0.03 | −0.21 *** | 0.00 |

| HCS-G (sc) | HCS-G (sm) | consc.1 | consc.2 | Openness | Impulsivity | Extraversion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCS-G (sm) | 0.55 *** | ||||||

| consc.1 | 0.15 ** | 0.08 | |||||

| consc.2 | 0.13 ** | 0.08 | 0.24 *** | ||||

| openness | 0.12 * | 0.10 * | 0.00 | 0.08 | |||

| impulsivity | −0.14 ** | −0.11 * | −0.27 *** | −0.46 *** | 0.05 | ||

| extraversion | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.17 *** | 0.08 | 0.26 *** | |

| neuroticism | 0.01 | −0.05 | −0.08 | 0.11 * | −0.07 | −0.08 | −0.30 *** |

| HCS-G (sc) | HCS-G (sm) | Health Literacy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCS-G (sm) | 0.55 *** | ||

| health literacy | 0.09 * | 0.15 ** | |

| frq. med. help | 0.09 * | −0.01 | 0.06 |

| Level of Invariance | Chi2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | Δ CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| configural | 45.123 | 16 | 0.952 | 0.910 | 0.088 | 0.035 | −0.002 |

| metric | 36.226 | 20 | 0.973 | 0.960 | 0.059 | 0.038 | 0.021 |

| scalar | 42.600 | 24 | 0.969 | 0.962 | 0.058 | 0.041 | −0.004 |

| conservative | 47.259 | 30 | 0.972 | 0.972 | 0.050 | 0.045 | 0.003 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marsall, M.; Engelmann, G.; Skoda, E.-M.; Teufel, M.; Bäuerle, A. Validation and Test of Measurement Invariance of the Adapted Health Consciousness Scale (HCS-G). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6044. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18116044

Marsall M, Engelmann G, Skoda E-M, Teufel M, Bäuerle A. Validation and Test of Measurement Invariance of the Adapted Health Consciousness Scale (HCS-G). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(11):6044. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18116044

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarsall, Matthias, Gerrit Engelmann, Eva-Maria Skoda, Martin Teufel, and Alexander Bäuerle. 2021. "Validation and Test of Measurement Invariance of the Adapted Health Consciousness Scale (HCS-G)" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 11: 6044. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18116044

APA StyleMarsall, M., Engelmann, G., Skoda, E.-M., Teufel, M., & Bäuerle, A. (2021). Validation and Test of Measurement Invariance of the Adapted Health Consciousness Scale (HCS-G). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 6044. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18116044