Challenging the Stereotypes: Unexpected Features of Sexual Exploitation among Homeless and Street-Involved Boys in Western Canada

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Surveys

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures of Sexual Exploitation

2.4. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

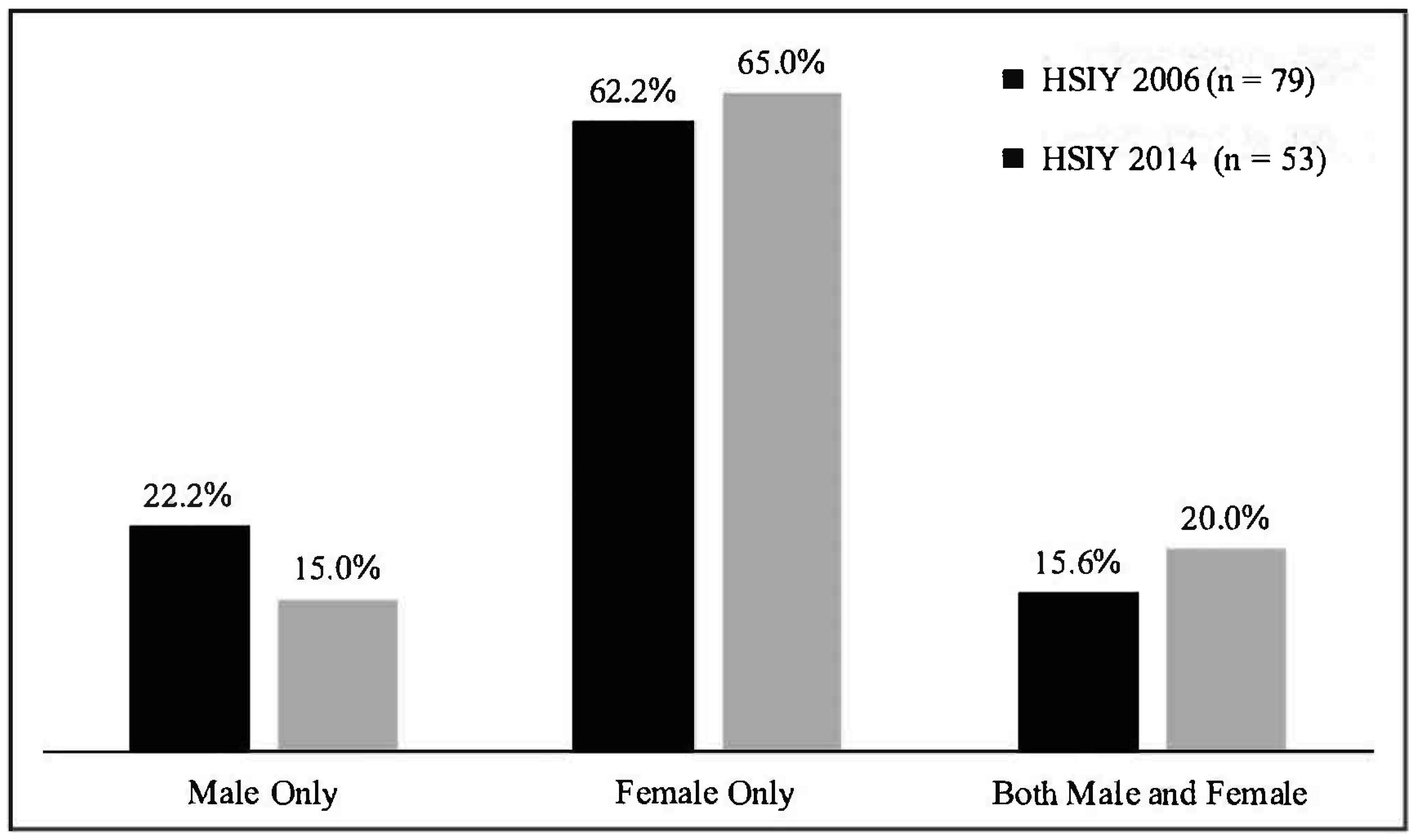

3.2. Genders of Exploiters

3.3. Housing Situations

3.4. Contexts and Venues of Sexual Exploitation

3.5. Risks and Consequences Associated with Sexual Exploitation among Boys

3.5.1. Which Came First? Timing of Exploitation vs. Homelessness

3.5.2. History of Sexual Abuse

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reid, J.A.; Piquero, A.R. Age-graded risks for commercial sexual exploitation of male and female youth. J. Interpers. Violence 2014, 29, 1747–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, K.; Moynihan, M.; Pitcher, C.; Francis, A.; English, A.; Saewyc, E. Rethinking research on sexual exploitation of boys: Methodological challenges and recommendations to optimize future knowledge generation. Child. Abus. Neglect. 2017, 66, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moynihan, M.; Mitchell, K.; Pitcher, C.; Havaei, F.; Ferguson, M.; Saewyc, E. A systematic review of the state of the literature on sexually exploited boys internationally. Child. Abus. Neglect. 2018, 76, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hounmenou, C.; O’Grady, C. A review and critique of the U.S. responses to the commercial sexual exploitation of children. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 98, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Article 2. Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child. on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography; Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights [OHCHR]: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000.

- Greenbaum, V.J. Commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of children in the United States. Curr. Probl. Pediatric Adolesc. Health Care 2014, 44, 245–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.; Patel, N. Broadening the discussion on “sexual exploitation”: Ethnicity, sexual exploitation and young people. Child. Abus. Rev. 2006, 15, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saewyc, E.M.; Drozda, C.; Rivers, R.; MacKay, L.; Maya, P. Which comes first: Sexual exploitation or other risk exposures among street-involved youth. In Youth Homeless in Canada: Implications for Policy and Practice; Gaetz, S., Karabanow, J., Eds.; Canadian Homelessness Research: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2013; pp. 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Saewyc, E.M.; Miller, B.B.; Rivers, R.; Matthews, J.; Hilario, C.; Hirakata, P. Competing discourses about youth sexual exploitation in Canadian news media. Can. J. Hum. Sex. 2013, 22, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockbain, E.; Brayley, H.; Ashby, M. Not Just a Girl Thing: A Large-Scale Comparison of Male and Female Users of Child Sexual Exploitation Services in the UK; University College London: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Josenhans, V.; Kavenagh, M.; Smith, S.; Wekerle, C. Gender, rights and responsibilities: The need for a global analysis of the sexual exploitation of boys. Child. Abus. Neglect. 2020, 110, 104291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.M.; Iritani, B.J.; Hallfors, D.D. Prevalence and correlates of exchanging sex for drugs or money among adolescents in the United States. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2006, 82, 354–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredlund, C.; Svensson, F.; Svedin, C.G.; Priebe, G.; Wadsby, M. Adolescents’ lifetime experience of selling sex: Development over five years. J. Child. Sex. Abus. 2013, 22, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, Y.; Nicholson, D.; Saewyc, E. Profile of high school students exchanging sex for substances in rural Canada. Can. J. Hum. Sex. 2012, 21, 29–40, PMC4690723. [Google Scholar]

- Kaestle, C.E. Selling and buying sex: A longitudinal study of risk and protective factors in adolescence. Prev. Sci. 2012, 13, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, W.; Hegna, K. Children and adolescents who sell sex: A community study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 56, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svedin, C.G.; Priebe, G. Selling sex in a population-based study of high school seniors in Sweden: Demographic and psychosocial correlates. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2007, 36, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.M.; Ennett, S.T.; Ringwalt, C.L. Prevalence and correlates of survival sex among runaway and homeless youth. Am. J. Public Health 1999, 89, 1406–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halcón, L.L.; Lifson, A.R. Prevalence and predictors of sexual risks among homeless youth. J. Youth Adolesc. 2004, 33, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, E.; Haley, N.; Leclerc, P.; Lemire, N.; Boivin, J.F.; Frappier, J.Y. Prevalence of HIV infection and risk behaviours among Montreal street youth. Int. J. STD AIDS 2000, 11, 241–247. [Google Scholar]

- Saewyc, E.M.; MacKay, L.J.; Anderson, J.; Drozda, C. It’s Not What You Think: Sexually Exploited youth in BC; The Stigma and Resilience among Vulnerable Youth Centre; University of British Columbia: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Walls, N.E.; Bell, S. Correlates of engaging in survival sex among homeless youth and young adults. J. Sex. Res. 2011, 48, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Towe, V.L.; Hasan, S.U.; Zafar, S.T.; Sherman, S.G. Street life and drug risk behaviors associated with exchanging sex among male street children in Lahore, Pakistan. J. Adolesc. Health 2009, 44, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppong Asante, K. Exploring age and gender differences in health risk behaviours and psychological functioning among homeless children and adolescents. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2015, 17, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, J.A. Exploratory review of route-specific, gendered, and age-graded dynamics of exploitation: Applying life course theory to victimization in sex trafficking in North America. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2012, 17, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, M.; Pitcher, C.; Saewyc, E. Interventions that foster healing among sexually exploited children and adolescents: A systematic review. J. Child. Sex. Abus. 2018, 27, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edinburgh, L.D.; Harpin, S.; Pape-Blabollil, J.; Saewyc, E. Assessing exploitation experiences of girls and boys seen at a Child Advocacy Center. Child. Abus. Negl. 2015, 46, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White Holman, C.; Goldberg, J.M. Ethical, legal, and psychosocial issues in care of transgender adolescents. Int. J. Transgend. 2006, 9, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonkin, R.S.; Murphy, A.; Sidhu, A. Our Kids Too—Sexually Exploited Youth in BC: An Adolescent Health Survey; The McCreary Centre Society: Burnaby, BC, Canada, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tonkin, R.S.; Peters, L.; Murphy, A. Adolescent Health Survey: Street Youth in Vancouver; The McCreary Centre Society: Burnaby, BC, Canada, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, A.; Poon, C.; Weigel, M. The McCreary Centre Society. No Place to Call Home: A Profile of Street Youth in British Columbia; The McCreary Centre Society: Burnaby, BC, Canada, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, T.N.; Reid, J.A. Gender stereotyping and sex trafficking: Comparative review of research on male and female sex tourism. J. Crime Justice 2015, 38, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Demographics | HSIY 2006 (N = 362) | HSIY 2014 (N = 318) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12–17 Years (n = 238) | 18+ Years * (n = 124) | 12–17 Years (n = 175) | 18+ Years (n = 143) | |

| % of Sexually Exploited Males | 27.3 (n = 65) | 11.3 (n = 14) | 26.3 (n = 46) | 4.9 (n = 7) |

| Sexual Orientation | ||||

| Straight | 68.3 | 75.0 | 73.2 | 71.4 |

| Bisexual | 11.7 | 16.7 | 12.2 | 14.3 |

| Gay | 8.3 | 8.3 | 2.4 | 14.3 |

| Not sure/Don’t have attractions | 11.7 | 0.0 | 12.2 | 0.0 |

| Born in Canada | 87.5 | 92.9 | 93.5 | 85.7 |

| Median (Range) | Median (Range) | Median (Range) | Median (Range) | |

| Age First Traded Sex | 14 (11, 17) | 15 (12, 17) | 14 (10, 17) | 17 (13, 17) |

| Housing Experiences | HSIY 2006 (n = 79) | HSIY 2014 (n = 53) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12–17 Years | 18+ Years * | 12–17 Years | 18+ Years * | |

| % Ever Lived in Precarious Housing | 54.1 | 78.6 | 58.5 | 100.0 |

| % Currently in Precarious Housing | 15.7 | 71.4 | 29.3 | 85.7 |

| Length of Time at Current Address | ||||

| <1 month | 25.0 | 21.4 | 33.3 | 85.7 |

| 2–6 months | 21.9 | 21.4 | 15.6 | 0.0 |

| 7–12 months | 12.5 | 7.1 | 11.1 | 14.3 |

| >1 year | 32.8 | 28.6 | 40.0 | 0.0 |

| No current address ‡ | 7.8 | 21.4 | -- | -- |

| Ever in Government Care | ||||

| Foster home | 27.9 | 50.0 | 60.5 | 71.4 |

| Group home | 27.9 | 64.3 | 31.6 | 28.6 |

| Youth agreement § | -- | -- | 13.5 | 28.6 |

| Custody centre | 55.4 | 84.6 | 17.6 | 33.3 |

| Contexts of Sexual Exploitation | HSIY 2006 (n = 79) | HSIY 2014 (n = 53) |

|---|---|---|

| % | % | |

| For Whom Sexual Activity Was Traded | ||

| Pimp | 17.9 | 10.4 |

| Escort agency | 4.5 | 8.3 |

| Supporting a friend, partner, or relative | 19.4 | 66.7 |

| Other | 7.5 | 4.2 |

| None of the above | 53.7 | 22.9 |

| Respondent Traded Sex for * | ||

| Food | 5.9 | 14.9 |

| Clothing | 10.0 | 13.0 |

| Shelter | 17.3 | 18.7 |

| Transportation | 13.7 | 8.9 |

| Money | 32.4 | 17.1 |

| Drugs or alcohol | 29.7 | 18.7 |

| Where Respondent Was Living When First Traded Sex | ||

| With their family | 25.5 | 41.2 |

| In a foster home | 8.5 | 0.0 |

| In a group home | 4.3 | 0.0 |

| In a shelter or safe house | 10.6 | 17.6 |

| Hostel, hotel, or motel | 4.3 | 11.8 |

| With a friend, boyfriend, or girlfriend | 10.6 | 11.8 |

| In my own place | 6.4 | 17.6 |

| On the street | 19.1 | 35.3 |

| Couch surfing | 6.4 | 17.6 |

| Which Came First | HSIY 2006 (n = 79) | HSIY 2014 (n = 53) |

|---|---|---|

| % | % | |

| Homeless vs. Sexual Exploitation First † | ||

| Homeless first | 72.9 | 60.0 |

| Traded sex first | 4.2 | 20.0 |

| Traded sex and became homeless at same age | 22.9 | 20.0 |

| Running Away vs. Sexual Exploitation First † | ||

| Ran away from home first | 45.7 | 55.6 |

| Traded sex first | 32.6 | 38.9 |

| Traded sex and ran away at same age | 21.7 | 5.6 |

| Kicked Out vs. Sexual Exploitation First † | ||

| Kicked out of home first | 37.8 | 52.5 |

| Traded sex first | 35.6 | 42.1 |

| Traded sex and kicked out of home at same age | 26.6 | 5.4 |

| Experiences of Sexual Abuse | HSIY 2006 (n = 79) | HSIY 2014 (n = 53) |

|---|---|---|

| % | % | |

| Forced to Have: “Sexual Intercourse’ (2006) or “Sex” (2014) | ||

| No | 57.0 | 80.8 |

| By another youth | 26.9 | 11.5 |

| By an adult | 19.2 | 9.6 |

| Ever Been Sexually Abused | 29.0 | 27.5 |

| Abused by a family member | 16.9 | 17.8 |

| Abused by a non-family member | 19.7 | 20.0 |

| By their mother | 2.8 | 6.7 |

| By their father | 2.8 | 6.7 |

| By their step-parent | 4.2 | 2.2 |

| By their foster parent | 7.0 | 2.2 |

| By another relative | 9.9 | 4.4 |

| By a friend | 8.5 | 8.9 |

| By a romantic partner | 4.2 | 2.2 |

| By a trick or date | 5.6 | 4.4 |

| By a pimp or agency manager | 2.8 | 2.2 |

| By a police officer | 2.8 | 4.4 |

| By a stranger | 4.2 | 11.1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saewyc, E.M.; Shankar, S.; Pearce, L.A.; Smith, A. Challenging the Stereotypes: Unexpected Features of Sexual Exploitation among Homeless and Street-Involved Boys in Western Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5898. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115898

Saewyc EM, Shankar S, Pearce LA, Smith A. Challenging the Stereotypes: Unexpected Features of Sexual Exploitation among Homeless and Street-Involved Boys in Western Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(11):5898. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115898

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaewyc, Elizabeth M., Sneha Shankar, Lindsay A. Pearce, and Annie Smith. 2021. "Challenging the Stereotypes: Unexpected Features of Sexual Exploitation among Homeless and Street-Involved Boys in Western Canada" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 11: 5898. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115898

APA StyleSaewyc, E. M., Shankar, S., Pearce, L. A., & Smith, A. (2021). Challenging the Stereotypes: Unexpected Features of Sexual Exploitation among Homeless and Street-Involved Boys in Western Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 5898. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115898