Wellbeing of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, Aotearoa (New Zealand) and the United States: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

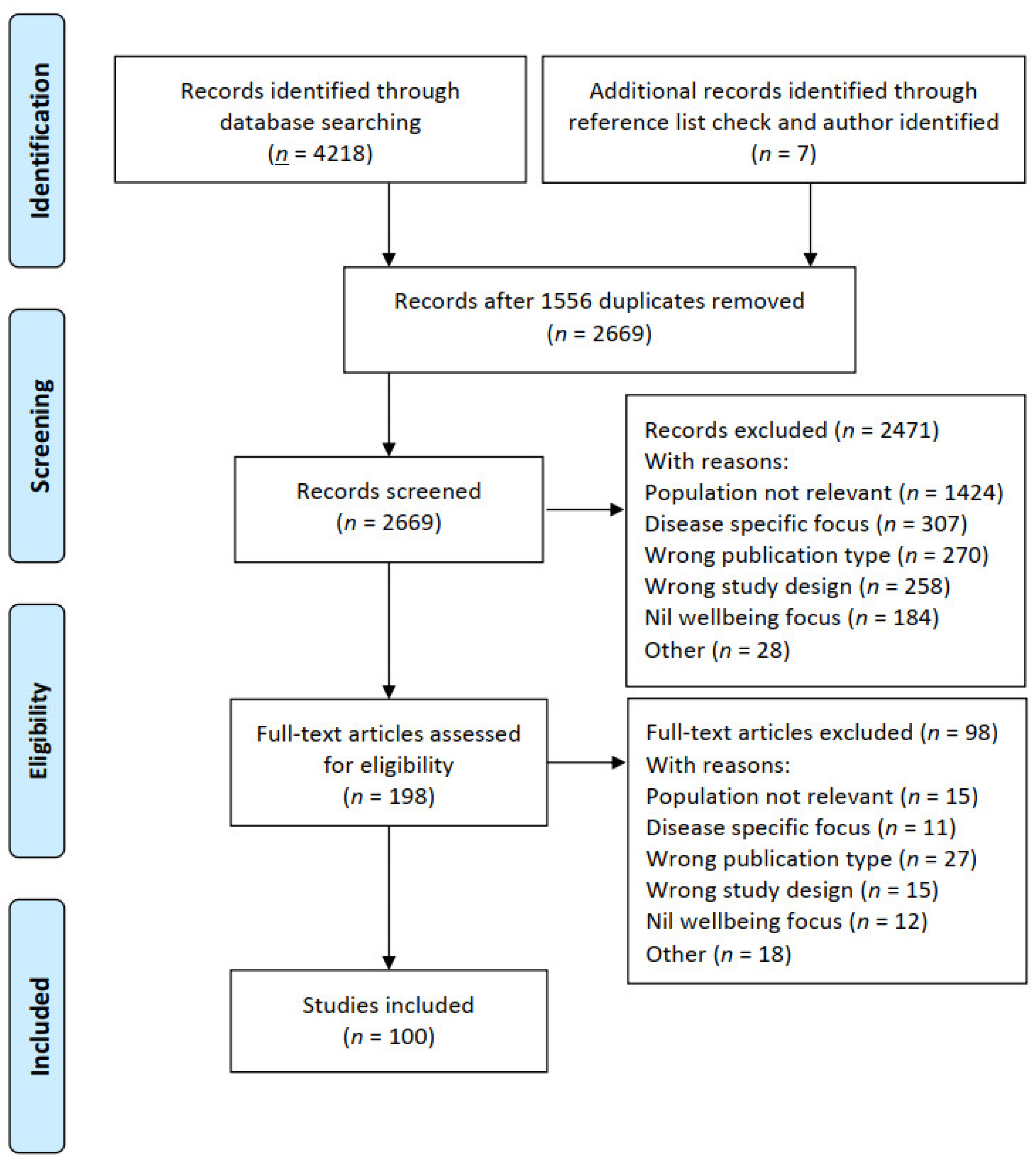

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Paper Characteristics

3.2. Thematic Synthesis Results

3.2.1. Canada

Holism/Wholism

“In the four components, I try to keep a balance… I think of the four areas, emotional, physical, spiritual and mental.”[36]

“The way any of your parts are treated will affect the whole, and it’s not just the way you treat them but the way that you are treated by the people and systems in your life, and the cultures that you are part of, or that impact you.”[19]

Culture

“…culture [is] essential for family well-being… [it is a] source of support that ‘bound individuals together’…”[28]

“…understanding who I am, who I am in terms of my family, my parents and my siblings, uncles, aunts and where I fit in the community, my relationships, aunts, uncles and all of that.”[36]

“It’s hard because we were raised white…But you know, I’m okay and I’m slowly learning more things about who I am—the connections and the boundaries.”[53]

“…we believe that the language is the culture and the culture is the language and the two go hand-in-hand.”[49]

Community and Family

“…talking to one or more others was essential to one’s well-being…talking was identified as the significant component of prevention, intervention, and healing.”[35]

“…as a marginalized people, [we] have a very big void to address in that area… [people] may not even know they belong to a community. And when you’re isolated like that we all tend to go to the dark side so to speak. A healthy community is a strong community.”[19]

“…looking after children… many of those children are now adults who come to me to tell me I was good to them while they were young. It feels really good inside to know that they have not forgotten me. It’s a rewarding feeling.”[22]

“The meat was divided accordingly, nobody was left behind. The men would be up all night carving the meat, and people would come by to pick up their share… The people… were looking after the community.”[24]

“Home is living in a [healthy] community where there are elders to undertake (Indigenous) teachings in sharing circles and different ceremonies. This is what makes us who we are. We get our self-identity through communal living and the teachings that go on in the communities.”[17]

“[Family] provided acceptance and a sense of belonging, pride and respect… provid[ing] them with hope, knowing that they can always turn to a family member or friends for support.”[30]

“…culture [is] essential for family well-being… [culture] ‘bound individuals together’ via sharing food, sharing language, hearing Elders’ stories and going out on the land.”[28]

“But the times have changed a lot and the young people are now in a place where they don’t really know the old traditional ways but they know the new way more… And it’s due to the fact that the elder’s voices are starting to, you know, diminish…I want the young people to know that. Elders are an important part of their life.”[35]

Land and Sea

“We have a connection to these places; our ancestors have occupied this space for thousands of years. The spirit of our people is here. We feel connected to our ancestors in this way.”[24]

“The respect that we need to show the land and its relatedness to us. We are the land. If the land is sick then it ain’t going to be very long before we’re going to get sick.”[54]

“…nature also becomes a guiding force or spiritual teacher that can help provide a sense of purpose and meaning in one’s life… land as teacher…”[32]

“These rapid [climate] changes were described as disrupting hunting, fishing, foraging, trapping, and traveling to cabins because people were unable to travel regularly (or at all) due to dangerous travel conditions and unpredictable weather patterns.”[26]

Resilience

“…culturally distinctive concepts of the person, the importance of collective history, the richness of Aboriginal languages and traditions, and the importance of individual and collective agency and activism”(p. 88 [61])

“Although, there were clear power imbalances, the elders still perceived Aboriginal people to have some agency and power over their existence and cultural practices, resisting the encroaching European and ‘White’ dominance.”[33]

“…I dealt with all those hard emotional issues and began to build my life as someone with self-esteem… I eventually settled into who I was, my culture, and learned about residential schools and started a path of forgiveness for those that had harmed me.”[38]

“They’d all take their bundles; their sacred items and they’d go up the river. Way up the river in the secret that’s where they’d do their ceremonies. They would never, ever do it in the community because it was against the law. You went to jail if you were caught doing those things.”[54]

“…[we] try to balance those two worlds… And those [cultural] teachings have to come back in order to know who we are and how to balance ourselves.”[36]

“I really believe it’s important that our [Aboriginal peoples] story is accurately portrayed. New people to this country, as well as most Canadian citizens, need to know our story, need to understand the impacts of colonization and the residential school system on our cultures, history and languages, and the future impacts these will have for generations to come.”[22]

Spirituality and Cultural Medicine

“…traditional healers [are] holistic practitioners, addressing body, mind, and spirit, which [is] different from the Western approach….”[34]

“One way to get in tune with the earth is to go to a sweat lodge… You go into the sweat praying and sweating. It is a cleansing and the whole time you are in there, you are praying… You feel so good when you come out of there.”[56]

“We each have our own souls and our ancestors are in our hearts. I think our ancestors are always with us and we walk with them.”[22]

Physical, Mental and Emotional Wellbeing

“Land-based, cultural activities are an important component of physical activity….”[31]

“…traditional foods are a lot healthier than the majority of store-bought foods, but due to circumstances such as the changing environment and decreasing numbers of traditional animals, a lot of community members are consuming more store-bought foods.”[52]

The First Nations older adults also felt that accessibility played a significant role in their ability to age well (safe, accessible, flexible, and affordable transportation in the city). This was particularly the case for the participants who identified as having a disability(ies).”[23]

“So mental health isn’t just mental health, it’s spiritual health, physical health and emotional health as well.”[19]

“mental health and well-being is not a new concept. However, given the history of colonization and especially the residential school legacy, it is essential to understand the increased significance of relationships on contemporary Indigenous peoples’ mental health and well-being.”[30]

“You can deal with intergenerational trauma as well by acknowledging it, realizing it, respecting it, learning from it, forgiving it… the biggest gift I ever gave myself, was really doing that hard trauma work.”[19]

“Respondents believed that not being gainfully engaged in anything significantly impacts the mind may eventually result in mental disorders. They said unemployment creates idleness and redundancy that negatively affects mood and physical wellbeing.”[36]

3.2.2. Aotearoa (New Zealand)

Māoritanga—Identity

“A collectivist approach to the men’s sense of self is lived through connections with whanau.”[64]

“Māori identity and culture includes obligations and responsibilities to attend activities and sites connected not only to their tribe, but also their family identity.”[70]

“Māori identity is linked to the earth by a sense of belonging to the land, being part of the land and being bonded together with the land.”[69]

Tikanga—Māori Customs

“One of Winiata’s aspirations is to ensure he passes on his practical skills and knowledge of ‘the bush’ to younger generations, most of whom now live in urban centres… [this] can ensure younger whānau have an embodied and emplaced experience of their belonging in this place as their tūrangawaewae (place of belonging).”[74]

“The ability for Māori leaders to not only be self-governing in their behaviour, but to develop others’ autonomy and self-determination, triggered satisfaction and consequently enhanced well-being.”[73]

“…a duty of iwi to act on their position as “sovereign iwi nations” was identified by several of the respondents… public policy discourse around iwi taking charge of the responses to the needs of their populations.”[67]

“Reciprocity is at the heart of manaakitanga, and rests upon a precept that being of service enhances the mana (authority/power) of others… Manaakitanga transforms mana through acts of generosity that enhances all, produces well-being… uplifting the mana of others in turn nourishes one’s own mana.”[75]

“…participants described barriers to participation in planning and active exclusion of Māori from decision making; for example, actions of the local council were identified as symptomatic of ongoing colonisation and oppression. A lack of voice in decision making…”[70]

“Participants conveyed feelings of grief and shame at being culturally disenfranchised… As long as Pākehā [colonisers] or politics are always running these [health care systems], I don’t know if we’re going to get any better.”[63]

Kotahitanga—Togetherness and Connection

“…[We have] a spiritual connectedness… with the land and the environment in which I live… It just makes me feel whole, and complete… my maunga (mountain) and… my awa (river)… directly affect my mental health and my physical health….”[63]

“…also understanding the relationship between the health and wellbeing of ourselves as people and the health and wellbeing of our lands, of our rivers, of our oceans, of our mountains, of all of the environment. So, I think there are definite links between the health and wellbeing of people and the health and wellbeing of our environment.”[76]

“I always think of whanaungatanga [relationships], manaakitanga [practising respect and kindness] and I think I’m here for the well-being of the people.”[75]

Whakapapa—The Importance of Genealogies

“If my whānau are not well, I am not well.”[72]

“…not saying that I’m unhappy now but I think if I’d accomplished that [weight-loss]… it would mean I’d be able to just do more with my daughter and my partner…”[63]

“The presence of elders at hui and other events was highlighted as particularly critical; without their expertise, there was a risk of adverse impacts on the wellbeing of the whole family, including the loss of tikanga (procedures) and kawa (ceremonial etiquette) knowledge.”[70]

“I belong here. I can stand here without challenge. My ancestors stood here before me. My children will stand tall here.”[74]

Wairuatanga—Spirituality

“…so all those things, spirituality, physical health, mental health, family health, I think are equal in Māoritanga… if ones out then the rest is out.”[76]

“…[when] it doesn’t happen [Indigenous custom] it makes me feel uneasy, like something’s not right… they [non-Indigenous people] didn’t do a karakia (Indigenous prayer/incantation)… and that made me feel different….”[63]

3.2.3. United States

Holism

“…[wellbeing] is the full integration of the physical, mental, emotional, cultural, and spiritual facets of a person….”[108]

“wellness is the ability when you get knocked off or you feel out of alignment, it’s the process of coming back to alignment. It’s the process of rebalancing.”[101]

Culture

“[through attempts to] Christianize and civilize and assimilate our people, we lost a lot. There’s some generations where some of our people weren’t able to learn the language, weren’t able to learn a lot of things about who we were, our traditional ways… That’s where we lost many of our values and cultural ways… pretty much forced into the assimilation.”[92]

“reawakening of our people… to not just understand, but value what we know as Native people, and how that’s instrumental to where we want to go in the future… [thus] strengthening the wellness of the individuals [and] community wellness.”[94]

“The Elders… teaching [the youth] traditional values and lifestyles and incorporating Western technology with subsistence activities, all of which contribute to their emotional well-being.”[106]

“When asked why language is so important Alayna replied, ‘it’s really important to our overall health and well-being. It has everything to do with who we are and we’re getting further and further away from that.’…”[101]

“I feel sad because I don’t speak Navajo, I know that I lost something.”[86]

“Even moderate exercise, such as staying busy in the community or engaging in subsistence activities, helps improve quality of life, both mentally and physically….”[106]

Spirituality and Cultural Medicine

“[United States Indigenous Peoples’] emphasized the belief that the path to true wellness and health implies matters of not only physical well-being, but functions of spiritual and mental health as well. Inherent in this idea of holistic balance is that traditional medicine is one of the primary pathways to restoring the imbalance….”[110]

“The Holy People are understood to play a crucial role in the efficacy of the ceremony and in maintaining one’s health and well-being throughout life.”[107]

“Ceremony and language remind people of ‘how all is a part of me and we are all a part of this,’ including nature and connection to higher powers, and how the continual work to ‘restore balance’ ensures the wellness of all parts.”[94]

“After our community performed this ritual we felt a difference among each other and in our homes and lives. We all felt lighter and happier. We smiled at each other more easily and things got better for our young people. The ritual brought us together and together we were stronger.”[80]

“I see a really great relationship between hula and health in all aspects of health, not just physical health, but mental and emotional health, spiritual health…”[108] Tribe/Community and Family

“Relationships provide a connection within community as well as an avenue through which to develop identity, both are important concepts….”[97]

“kūpuna (Elders)… pass down culture, religion, values, in the right way to the next generation… kūpuna looks to the past and future. Kūpuna are the ones with the knowledge—wisdom. They respect Hawaiian values and deserve respect.”[81]

“…familial relationships and spending time together was a large contributor to many participants’ definition of health and wellness.”[118]

“Participants cited family relationships as integral to their health and wellness, as well as a source of ongoing stress.”[96]

Land, Sea and Subsistence-Based Living

“When we think about a healthy community…it includes… love of our natural world… and recogn(izing) our deep connection to it.”[94]

“…I am… a spiritual being connected to land, mountain, sea, especially the ocean….”[113]

‘‘Health comes from the land, and how we take care of the people and the land.”[85]

“Many participants expressed that this subsistence lifestyle is at the core of wellness for Yup’ik people, frequently referring to it as ‘the lifestyle’ or ‘the way of life’.”[119]

“Consistent with this emphasis on the subsistence lifestyle for health and wellness, participants in all focus groups remarked on the superiority of traditional natural foods over store-bought food that is processed and imported. Participants described how native foods provide better nutrition, better taste, keep hunger satiated for a longer time and increase physical health.”[119]

Resilience

“When probed on what it was that brought tears to her eyes, she added, ‘I think it’s just knowing what we went through and that we’re still trying to keep our culture and still live in the modern way that we have to’.”[86]

“…participants and workgroup members also emphasized the capacity for resiliency, adaptation, and cultural renewal evidenced by [the Indigenous peoples in the United States].”[117]

“Gaining independence enhanced the well-being of many participants… Learning to adjust was essential for participants who maintained well-being.”[103]

Basic Needs

“Not having to fret about simple things like food. To be able to not lavishly but comfortably do things you’d like to do. Basically that everyone is healthy. I don’t really look at it so much as status but I mean, just being financially sort of stable… Well-being is a roof over our heads, clothes on our backs, food in our stomachs, and our health.”[87]

“Her jobs were demanding, stressful, and took away from family time, all of which may have contributed to diminished well-being.”[103]

“For most of the participants, it was best if the care provider was Hawaiian or knew Hawaiian ways and respected Hawaiian culture.”[81]

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Exclusion Reason | If … |

|---|---|

| foreign language | Not English |

| population not relevant | No Indigenous adults (18+) in Canada, Aotearoa (New Zealand) and the United States included in paper |

| wrong publication type | Grey literature, poster abstracts, newspaper articles, case reports and dissertations, opinion piece, position statement |

| disease specific focus | If the study cohort, or the paper itself, has a focus on one specific disease, exclude |

| Systems focus | If the study is looking too narrowly at a specific system—for example a health service—then too narrow for our review |

| nil wellbeing focus | Doesn’t report factors of wellbeing or quality of life |

| review | Systematic or other reviews relevant—for checking ref lists |

| wrong study design | No mention of qualitative results or new empirical data in abstract, and non-relevant reviews |

References

- Cooke, M.; Mitrou, F.; Lawrence, D.; Guimond, E.; Beavon, D. Indigenous well-being in four countries: An application of the UNDP’S Human Development Index to Indigenous Peoples in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2007, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, I.; Robson, B.; Connolly, M.; Al-Yaman, F.; Bjertness, E.; King, A.; Tynan, M.; Madden, R.; Bang, A.; Coimbra, C.E.A.; et al. Indigenous and tribal peoples’ health (The Lancet–Lowitja Institute Global Collaboration): A population study. Lancet 2016, 388, 131–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracey, M.; King, M. Indigenous health part 1: Determinants and disease patterns. Lancet 2009, 374, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulver, L.J.; Haswell, M.R.; Ring, I.; Waldon, J.; Clark, W.; Whetung, V.; Kinnon, D.; Graham, C.; Chino, M.; LaValley, J.; et al. Indigenous Health—Australia, Canada, Aotearoa New Zealand and the United States—Laying claim to a future that embraces health for us all. In World Health Report (2010); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- King, M.; Smith, A.; Gracey, M. Indigenous health part 2: The underlying causes of the health gap. Lancet 2009, 374, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, M.A. Indigenous Worldviews, Knowledge, and Research: The Development of an Indigenous Research Paradigm. J. Indig. Voices Soc. Work 2010, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, C.; Nettleton, C.; Porter, J.; Willis, R.; Clark, S. Indigenous peoples’ health—Why are they behind everyone, everywhere? Lancet 2005, 366, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, S.; Soucar, B.; Sherman-Slate, E.; Luna, L. The Social Construction of Beliefs About Cancer: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Racial Differences in the Popular Press. J. Appl. Biobehav. Res. 2007, 9, 201–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2013–2023; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2013.

- Angell, B.; Muhunthan, J.; Eades, A.-M.; Cunningham, J.; Garvey, G.; Cass, A.; Howard, K.; Ratcliffe, J.; Eades, S.; Jan, S. The health-related quality of life of Indigenous populations: A global systematic review. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 25, 2161–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, T.L.; Anderson, K.; Garvey, G.; Cunningham, J.; Ratcliffe, J.; Tong, A.; Whop, L.J.; Cass, A.; Dickson, M.; Howard, K. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s domains of wellbeing: A comprehensive literature review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 233, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, K.; Anderson, K.; Cunningham, J.; Cass, A.; Ratcliffe, J.; Whop, L.J.; Dickson, M.; Viney, R.; Mulhern, B.; Tong, A.; et al. What Matters 2 Adults: A study protocol to develop a new preference-based wellbeing measure with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults (WM2Adults). BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad, O.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software; QSR International Pty Ltd.: Burlington, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adelson, N. Health beliefs and the politics of Cree well-being. Health Interdiscip. J. Soc. Study Health Illn. Med. 1998, 2, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaazi, D.A.; Masuda, J.R.; Evans, J.; Distasio, J. Therapeutic landscapes of home: Exploring Indigenous peoples’ experiences of a Housing First intervention in Winnipeg. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 147, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, M.; Howell, T.; Gomes, T. Moving toward holistic wellness, empowerment and self-determination for Indigenous peoples in Canada: Can traditional Indigenous health care practices increase ownership over health and health care decisions? Can. J. Public Health 2016, 107, e393–e398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, M.D. We need to not be footnotes anymore’: Understanding Métis people’s experiences with mental health and wellness in British Columbia, Canada. Public Health 2019, 176, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, J.G. Conceptions and dimensions of health and well-being for Métis women in Manitoba. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2004, 63, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, J.G. Health and Well-Being for Métis Women in Manitoba. Can. J. Public Health 2005, 96, S22–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baskin, C.; Davey, C.J. Grannies, Elders, and Friends: Aging Aboriginal Women in Toronto. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2014, 58, 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks-Cleator, L.A.; Giles, A.R.; Flaherty, M. Community-level factors that contribute to First Nations and Inuit older adults feeling supported to age well in a Canadian city. J. Aging Stud. 2019, 48, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castleden, H.; Bennett, E.; Lewis, D.; Martin, D. “Put It Near the Indians”: Indigenous Perspectives on Pulp Mill Contaminants in Their Traditional Ter-ritories (Pictou Landing First Nation, Canada). Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2017, 11, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condon, R.G.; Collings, P.; Wenzel, G. The Best Part of Life: Subsistence Hunting, Ethnicity, and Economic Adaptation among Young Adult Inuit Males. Arctic 1995, 48, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willox, A.C.; Harper, S.L.; Ford, J.D.; Landman, K.; Houle, K.; Edge, V.L. “From this place and of this place”: Climate change, sense of place, and health in Nunatsiavut, Canada. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fillion, M.; Laird, B.; Douglas, V.; Van Pelt, L.; Archie, D.; Chan, H.M. Development of a strategic plan for food security and safety in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region, Canada. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2014, 73, 25091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, S.L.; Parent, V.; Dupéré, V. Communities being well for family well-being: Exploring the socio-ecological determinants of well-being in an Inuit community of Northern Quebec. Transcult Psychiatry 2018, 55, 120–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, S.L.; Hordyk, S.; Etok, N.; Weetaltuk, C. Exploring Community Mobilization in Northern Quebec: Motivators, Challenges, and Resilience in Action. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 64, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, H.; Martin, S. Narrative descriptions of miyo-mahcihoyān (physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual well-being) from a contemporary néhiyawak (Plains Cree) perspective. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2016, 10, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, S.L.; Edge, V.L.; Ford, J.D.; Willox, A.C.; Wood, M.M.; IHACC Research Team; McEwen, S.A. Ricg Climate-sensitive health priorities in Nunatsiavut, Canada. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatala, A.R.; Morton, D.; Njeze, C.; Bird-Naytowhow, K.; Pearl, T. Re-imagining miyo-wicehtowin: Human-nature relations, land-making, and wellness among Indigenous youth in a Canadian urban context. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 230, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatala, A.R.; Desjardins, M.; Bombay, A. Reframing Narratives of Aboriginal Health Inequity: Exploring Cree Elder Re-silience and Well-Being in Contexts of Historical Trauma. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1911–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keightley, M.L.; King, G.E.; Jang, S.-H.; White, R.J.; Colantonio, A.; Minore, J.B.; Katt, M.V.; Cameron, D.A.; Bellavance, A.M.; Longboat-White, C.H. Brain Injury from a First Nations’ Perspective: Teachings from Elders and Traditional Healers. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2011, 78, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kral, M.J.; Idlout, L.; Minore, J.B.; Dyck, R.J.; Kirmayer, L.J. Unikkaartuit: Meanings of Well-Being, Unhappiness, Health, and Community Change Among Inuit in Nunavut, Canada. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2011, 48, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyoon-Achan, G.; Philips-Beck, W.; Lavoie, J.; Eni, R.; Sinclair, S.; Kinew, K.A.; Ibrahim, N.; Katz, A. Looking back, moving forward: A culture-based framework to promote mental wellbeing in Manitoba First Nations communities. Int. J. Cult. Ment. Health 2018, 11, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemelin, H.; Matthews, D.; Mattina, C.; McIntyre, N.; Johnston, M.; Koster, R. Climate change, wellbeing and resilience in the Weenusk First Nation at Peawanuck: The Moccasin Telegraph goes global. Rural. Remote Health 2010, 10, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matheson, K.; Bombay, A.; Dixon, K.; Anisman, H. Intergenerational communication regarding Indian Residential Schools: Implications for cultural identity, perceived discrimination, and depressive symptoms. Transcult. Psychiatry 2019, 57, 304–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikraszewicz, K.; Richmond, C. Paddling the Biigtig: Mino biimadisiwin practiced through canoeing. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 240, 112548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, S. Language and identity in an Indigenous teacher education program. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2019, 78, 1506213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motz, T.; Currie, C. Racially-motivated housing discrimination experienced by Indigenous postsecondary students in Canada: Impacts on PTSD symptomology and perceptions of university stress. Public Health 2019, 176, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, J.; Gallagher, J.; Wylie, L.; Bingham, B.; Lavoie, J.; Alcock, D.; Johnson, H. Transforming First Nations’ health governance in British Columbia. Int. J. Health Gov. 2016, 21, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, J.; Gabel, C. Using Photovoice to Understand Barriers and Enablers to Southern Labrador Inuit Intergenerational Interaction. J. Intergener. Relatsh. 2018, 16, 351–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, B.; Burnett, K.; Hay, T.; Skinner, K. The Community Food Environment and Food Insecurity in Sioux Lookout, Ontario: Understanding the Relationships between Food, Health, and Place. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2019, 14, 762–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlee, B.; O’Neil, J. “The Dene Way of Life”: Perspectives on Health from Canada’s North. J. Can. Stud. 2007, 41, 112–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlee, B.; Berkes, F. Health of the Land, Health of the People: A Case Study on Gwich’in Berry Harvesting in Northern Canada. EcoHealth 2005, 2, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, J.P.; Willox, A.C.; Ford, J.D.; Shiwak, I.; Wood, M. Protective factors for mental health and well-being in a changing climate: Perspectives from Inuit youth in Nunatsiavut, Labrador. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 141, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, C.; Elliott, S.; Matthews, R.; Elliott, B. The political ecology of health: Perceptions of environment, economy, health and well-being among ‘Namgis First Nation. Health Place 2005, 11, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schill, K.; Terbasket, E.; Thurston, W.E.; Kurtz, D.; Page, S.; McLean, F.; Jim, R.; Oelke, N. Everything Is Related and It All Leads Up to My Mental Well-Being: A Qualitative Study of the Determinants of Mental Wellness Amongst Urban Indigenous Elders. Br. J. Soc. Work. 2019, 49, 860–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, S.J.; Thomas, S.; O’Neill, K.; Brondgeest, C.; Thomas, J.; Beltran, J.; Hunt, T.; Yassi, A. Visual Storytelling, Intergenerational Environmental Justice and Indigenous Sovereignty: Exploring Images and Stories amid a Contested Oil Pipeline Project. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S.L. Promoting Indigenous mental health: Cultural perspectives on healing from Native counsellors in Canada. Int. J. Health Promot. Educ. 2008, 46, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, B.Y.; Gough, W.A.; Edwards, V.; Tsuji, L.J.S. The impact of climate change on the well-being and lifestyle of a First Nation community in the western James Bay region. Can. Geogr. 2013, 57, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G.E.; Cameron, R.E.; Fuller-Thomson, E. Walking the red road: The role of First Nations grandparents in promoting cultural well-being. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2013, 76, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobias, J.K.; Richmond, C.A. “That land means everything to us as Anishinaabe…”: Environmental dispossession and resilience on the North Shore of Lake Superior. Health Place 2014, 29, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waddell, C.M.; Robinson, R.; Crawford, A. Decolonizing Approaches to Inuit Community Wellness: Conversations with Elders in a Nunavut Community. Can. J. Community Ment. Health 2017, 36, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K. Therapeutic landscapes and First Nations peoples: An exploration of culture, health and place. Health Place 2003, 9, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurba, M.; Bullock, R. Bioenergy development and the implications for the social wellbeing of Indigenous peoples in Canada. Ambio 2020, 49, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gone, J.P. The Red Road to Wellness: Cultural Reclamation in a Native First Nations Community Treatment Center. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2011, 47, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias, B.; Busby, K.; Martens, P. One little, too little: Counting Canada’s indigenous people for improved health reporting. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 138, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjana, B.; Alana, M. What does ‘holism’ mean in Indigenous mental health? Univ. West. Ont. Med. J. 2017, 86, 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer, L.J.; Dandeneau, S.; Marshall, E.; Phillips, M.K.; Williamson, K.J. Rethinking Resilience from Indigenous Perspectives. Can. J. Psychiatry 2011, 56, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beavis, B.S.; McKerchar, C.; Maaka, J.; Mainvil, L.A. Exploration of Māori household experiences of food insecurity. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 76, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, R.; Smith, C.; Hale, L.; Kira, G.; Tumilty, S. Understanding obesity in the context of an Indigenous population—A qualitative study. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2017, 11, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, E.; Breheny, M. Dependence on place: A source of autonomy in later life for older Māori. J. Aging Stud. 2016, 37, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapeta, J.; Palmer, F.; Kuroda, Y. Cultural identity, leadership and well-being: How indigenous storytelling contributed to well-being in a New Zealand provincial rugby team. Public Health 2019, 176, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkirk, J.; Wilson, L.H. A Call to Wellness—Whitiwhitia i te ora: Exploring Māori and Occupational Therapy Perspectives on Health. Occup. Ther. Int. 2014, 21, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aho, K.L.-T.; Fariu-Ariki, P.; Ombler, J.; Aspinall, C.; Howden-Chapman, P.; Pierse, N. A principles framework for taking action on Māori/Indigenous Homelessness in Aotearoa/New Zealand. SSM Popul. Health 2019, 8, 100450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, G.; Lyons, A. Conceptualizing Mind, Body, Spirit Interconnections Through, and Beyond, Spiritual Healing Practices. Explore 2014, 10, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, G.T.; Lyons, A. Maori healers’ views on wellbeing: The importance of mind, body, spirit, family and land. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 1756–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awa, T.A.K.R.N.; Macmillan, A.K.; Kahungunu, R.G.J.N. Indigenous Māori perspectives on urban transport patterns linked to health and wellbeing. Health Place 2013, 23, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rata, A.; Liu, J.H.; Hanke, K. Te ara hohou rongo (The path to peace): Mäori conceptualisations of inter-group forgiveness. N. Z. J. Psychol. 2008, 37, 18–30. [Google Scholar]

- Rawson, E. Te Waioratanga: Health promotion practice—The importance of Māori cultural values to wellbeing in a disaster context and beyond. Australas. J. Disaster Trauma Stud. 2016, 20, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Roche, M.A.; Haar, J.M.; Brougham, D. Māori leaders’ well-being: A self-determination perspective. Leadership 2018, 14, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rua, M.; Hodgetts, D.; Stolte, O. Māori men: An indigenous psychological perspective on the interconnected self. N. Z. J. Psychol. 2017, 46, 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Spiller, C.; Erakovic, L.; Henare, M.; Pio, E. Relational Well-Being and Wealth: Māori Businesses and an Ethic of Care. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willing, E.; Paine, S.-J.; Wyeth, E.; Ao, B.T.; Vaithianathan, R.; Reid, P. Indigenous voices on measuring and valuing health states. Altern. Int. J. Indig. Peoples 2020, 16, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D. The significance of a culturally appropriate health service for Indigenous Māori women. Contemp. Nurse 2008, 28, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moorfield, J.C. Te Aka: Maori-English, English-Maori Dictionary and Index; Longman Pearson: Auckland, New Zealand, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, N.S.; Jones, M.; Frazier, S.M.; Percy, C.; Flores, M.; Bauer, U.E. Tribal Practices for Wellness in Indian Country. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2019, 16, E97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayunerak, P.; Alstrom, D.; Moses, C.; Charlie, J.; Rasmus, S.M. Yup’ik culture and context in Southwest Alaska: Community member perspectives of tradition, social change, and prevention. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2014, 54, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, C.V.; Mokuau, N.; Ka’Opua, L.S.; Kim, B.J.; Higuchi, P.; Braun, K.L. Listening to the voices of native Hawaiian elders and ‘ohana caregivers: Discussions on aging, health, and care preferences. J. Cross Cult. Gerontol. 2014, 29, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehler, J.A. Traditional Crow Indian Health Beliefs and Practices. J. Holist. Nurs. 1992, 10, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnette, C.E. Family and cultural protective factors as the bedrock of resilience and growth for Indigenous women who have experienced violence. J. Fam. Soc. Work. 2018, 21, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnette, C.E.; Clark, C.B.; Rodning, C.B. “Living off the Land”: How Subsistence Promotes Well-Being and Resilience among Indigenous Peoples of the Southeastern United States. Soc. Serv. Rev. 2018, 92, 369–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, C.; Garroutte, E.; Noonan, C.; Buchwald, D. Using PhotoVoice to Promote Land Conservation and Indigenous Well-Being in Oklahoma. EcoHealth 2018, 15, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christiansen, K.; Gadhoke, P.; Pardilla, M.; Gittelsohn, J. Work, worksites, and wellbeing among North American Indian women: A qualitative study. Ethn. Health 2019, 24, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danes, S.M.; Garbow, J.; Jokela, B.H. Financial Management and Culture: The American Indian Case. J. Financ. Couns. Plan. 2016, 27, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, Z. Chokka-Chaffa’ Kilimpi’, Chikashshiyaakni’ Kilimpi’: Strong Family, Strong Nation. Am. Indian Alsk. Nativ. Ment. Health Res. 2011, 18, 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elm, J.H.L.; Lewis, J.P.; Walters, K.L.; Self, J.M. “I’m in this world for a reason”: Resilience and recovery among American Indian and Alaska Native two-spirit women. J. Lesbian Stud. 2016, 20, 352–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesen, B.J.; Cross, T.L.; Jivanjee, P.; Thirstrup, A.; Bandurraga, A.; Gowen, L.K.; Rountree, J. Meeting the Transition Needs of Urban American Indian/Alaska Native Youth through Culturally Based Services. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2014, 42, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodkind, J.R.; Gorman, B.; Hess, J.M.; Parker, D.P.; Hough, R.L. Reconsidering Culturally Competent Approaches to American Indian Healing and Well-Being. Qual. Health Res. 2015, 25, 486–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grayshield, L.; Rutherford, J.J.; Salazar, S.B.; Mihecoby, A.L.; Luna, L.L. Understanding and Healing Historical Trauma: The Perspectives of Native American Elders. J. Ment. Health Couns. 2015, 37, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin-Pierce, T. “When I Am Lonely the Mountains Call Me”: The Impact of Sacred Geography on Navajo Psychological Well Being. Am. Indian Alsk. Nativ. Ment. Health Res. 1997, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgendorf, A.; Reiter, A.G.; Gauthier, J.; Krueger, S.; Beaumier, K.; Corn, R.; Moore, T.R.; Roland, H.; Wells, A.; Pollard, E.; et al. Language, Culture, and Collectivism: Uniting Coalition Partners and Promoting Holistic Health in the Menominee Nation. Health Educ. Behav. 2019, 46, 81S–87S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodge, D.R.; Limb, G.E. Conducting Spiritual Assessments with Native Americans: Enhancing Cultural Competency in Social Work Practice Courses. J. Soc. Work. Educ. 2010, 46, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulen, E.; Hardy, L.J.; Teufel-Shone, N.; Sanderson, P.R.; Schwartz, A.L.; Begay, R.C. Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR): A Dynamic Process of Health care, Provider Perceptions and American Indian Patients’ Resilience. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2019, 30, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacson, M.J. Native Elder and Youth Perspectives on Mental Well-Being, the Value of the Horse, and Navigating Two Worlds. Online J. Rural Nurs. Health Care 2018, 18, 265–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, M.M.; Sabzalian, L.; Johnson, S.R.; Jansen, J.; Morse, G.S.N. “We Need to Make Action NOW, to Help Keep the Language Alive”: Navigating Tensions of Engaging Indigenous Educational Values in University Education. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 64, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kading, M.L.; Gonzalez, M.B.; Herman, K.A.; Gonzalez, J.; Walls, M.L. Living a Good Way of Life: Perspectives from American Indian and First Nation Young Adults. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 64, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodish, S.R.; Gittelsohn, J.; Oddo, V.M.; Jones-Smith, J.C. Impacts of casinos on key pathways to health: Qualitative findings from American Indian gaming communities in California. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, T.M. The frontline of refusal: Indigenous women warriors of standing rock. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2018, 31, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassetter, J.H. The Integral Role of Food in Native Hawaiian Migrants’ Perceptions of Health and Well-Being. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2012, 22, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassetter, J.H.; Callister, L.C.; Miyamoto, S.Z. Perceptions of Health and Well-Being Held by Native Hawaiian Migrants. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2011, 23, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.P. The Importance of Optimism in Maintaining Healthy Aging in Rural Alaska. Qual. Health Res. 2013, 23, 1521–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J. The Role of the Social Engagement in the Definition of Successful Ageing among Alaska Native Elders in Bristol Bay, Alaska. Psychol. Dev. Soc. 2014, 26, 263–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.P. Successful aging through the eyes of Alaska Native elders. What it means to be an elder in Bristol Bay, AK. Gerontologist 2011, 51, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewton, E.L.; Bydone, V. Identity and healing in three Navajo religious traditions: Sa’ah naagháí bik’eh hózh. Med. Anthropol. Q. 2000, 14, 476–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Look, M.A.; Maskarinec, G.G.; de Silva, M.; Seto, T.; Mau, M.L.; Kaholokula, J.K. Kumu Hula Perspectives on Health. Hawai’i J. Med. Public Health 2014, 73, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, F.M. “Water Is Life”: Using Photovoice to Document American Indian Perspectives on Water and Health. Soc. Work Res. 2018, 42, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, J.F.; Momper, S.L.; Fong, T.W. Crystalizing the Role of Traditional Healing in an Urban Native American Health Center. Community Ment. Health J. 2015, 51, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorehead, V.D., Jr.; Gone, J.P.; December, D. A Gathering of Native American Healers: Exploring the Interface of Indigenous Tradition and Professional Practice. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2015, 56, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odom, S.K.; Jackson, P.; Derauf, D.; Inada, M.K.; Aoki, A.H. Pilinaha: An Indigenous Framework for Health. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, 3, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oneha, M.F. Ka mauli o ka’oina a he mauli kanaka: An ethnographic study from an Hawaiian sense of place. Pac. Health Dialog 2001, 8, 299–311. [Google Scholar]

- Shea, H.; Mosley-Howard, G.S.; Baldwin, D.; Ironstrack, G.; Rousmaniere, K.; Schroer, J.E. Cultural revitalization as a restorative process to combat racial and cultural trauma and promote living well. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2019, 25, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skewes, M.C.; Blume, A.W. Understanding the link between racial trauma and substance use among American Indians. Am. Psychol. 2019, 74, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trout, L.; Wexler, L.; Moses, J. Beyond two worlds: Identity narratives and the aspirational futures of Alaska Native youth. Transcult. Psychiatry 2018, 55, 800–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, A.E.; Williams, E.; Suzukovich, E.; Strangeman, K.; Novins, D. A Mental Health Needs Assessment of Urban American Indian Youth and Families. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2012, 49, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, H.J.; Brennan, A.C.; Tress, S.F.; Joseph, D.H.; Baldwin, J.A. Exploring health and wellness among Native American adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities and their family caregivers. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2020, 33, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolsko, C.; Lardon, C.; Hopkins, S.; Ruppert, E. Conceptions of Wellness among the Yup’ik of the Yukon–Kuskokwim Delta: The Vitality of Social and Natural Connection. Ethn. Health 2006, 11, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, M.; Gallagher, M.; Hodge, F.; Cwik, M.; O’Keefe, V.; Jacobs, B.; Adler, A. Identification in a time of invisibility for American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States. Stat. J. IAOS 2019, 35, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brascoupé, S. Strengthening Traditional Economies and Perspectives. In Sharing the Harvest, the Road to Self-Reliance: Report of the National Round Table on Aboriginal Economic Development and Resources; Canada Communication Group: Ottawa, Canada, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Corntassel, J. Re-envisioning resurgence: Indigenous pathways to decolonization and sustainable self-determination. Decolon. Indig. Educ. Soc. 2012, 1, 86–101. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milyavskaya, M.; Koestner, R. Psychological needs, motivation, and well-being: A test of self-determination theory across multiple domains. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 50, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuokkanen, R. Restructuring Relations: Indigenous Self-Determination, Governance, and Gender; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cram, F.; Smith, L.; Johnstone, W. Mapping the themes of Maori talk about health. N. Z. Med. J. 2003, 116. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman, D. Maslow’s hierarchy and social and emotional wellbeing. Aborig. Islander Health Work. J. 2010, 33, 27–29. [Google Scholar]

| Indigenous Population Terms | Quality of Life and Wellbeing Terms | Limiters |

|---|---|---|

| “American Indian *” OR “First Nation *” OR “First people *” OR Indigenous OR Inuit * OR Māori * OR Maori * OR “Native American *” OR ((Canadian OR Canada) AND Aborigin *) OR “native Canadian” OR “Indigenous population *” OR Metis OR Métis OR “Alaska * Native” OR “Native Alaska *” OR “Native Hawaiian *” OR tribal (TI/AB) 1 | wellbeing OR well-being OR SEWB OR “quality of life” OR HR-QOL OR HRQOL OR QOL OR wellness (TI/AB) 1 | English, Human, Peer-reviewed, research paper, inception to year 2020 |

| Country | Themes | Sub-Themes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canada (n = 43) | |||

| Holism/Wholism (n = 15) | [16,19,20,21,30,32,35,37,42,45,49,51,52,56,58] | ||

| Culture (n = 33) |

| [16,19,20,21,22,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,35,36,37,38,39,40,42,43,45,47,48,49,51,52,53,54,55,56,58] | |

| Community and Family (n = 31) | [17,18,19,20,22,23,24,25,27,28,29,30,31,35,36,37,39,41,42,43,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,53,54,55,57] | ||

| Land and Sea (n = 27) | [16,24,25,26,27,28,31,32,35,36,37,39,40,42,43,47] | ||

| Resilience (n = 23) | [16,19,22,23,24,28,29,33,35,36,38,41,42,45,48,49,50,53,54,55,57] | ||

| Spirituality and Cultural Medicine (n = 18) | [17,18,19,20,21,22,30,32,33,34,36,42,45,46,53,54,56,58] | ||

| Physical, Mental and Emotional Wellbeing (n = 26) | [17,19,20,21,22,23,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,36,38,42,44,46,47,49,52,53,54,56,58] | ||

| Aotearoa (New Zealand; n = 16) | |||

| Māoritanga—identity (n = 9) | [64,66,69,70,71,72,74,75,77] | ||

| Tikanga—Māori customs (n = 12) |

| [62,63,64,65,67,69,70,71,72,73,74,75] | |

| Kotahitanga—togetherness and connection (n = 14) |

| [62,63,64,65,66,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76] | |

| Whakapapa—importance of genealogies (n = 15) |

| [62,63,64,65,66,67,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77] | |

| Wairuatanga—spirituality (n = 8) |

| [63,66,68,69,72,75,76,77] | |

| United States (n = 41) | |||

| Holism (n = 10) | [87,94,95,99,101,107,108,110,112,117] | ||

| Culture (n = 30) |

| [79,80,81,83,85,86,88,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,101,103,105,106,107,111,113,114,115,116,117,118,119] | |

| Spirituality and Cultural Medicine (n = 28) |

| [80,81,82,85,86,87,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,97,99,100,101,104,106,107,108,110,111,112,113,117,118,119] | |

| Tribe/Community and Family (n = 29) | [79,80,81,83,84,86,87,88,89,90,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,103,104,105,106,107,112,113,114,116,117,118,119] | ||

| Land, Sea and Subsistence-based living (n = 28) |

| [79,80,81,84,85,86,87,91,93,94,96,97,99,100,101,102,104,105,106,107,109,112,113,114,116,117,118,119] | |

| Resilience (n = 21) | [79,80,82,86,89,90,91,95,96,97,98,99,101,103,104,106,107,110,113,116,117] | ||

| Basic Needs (n = 17) | [81,86,87,90,91,94,95,96,100,101,103,105,110,111,115,117,118] | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gall, A.; Anderson, K.; Howard, K.; Diaz, A.; King, A.; Willing, E.; Connolly, M.; Lindsay, D.; Garvey, G. Wellbeing of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, Aotearoa (New Zealand) and the United States: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5832. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115832

Gall A, Anderson K, Howard K, Diaz A, King A, Willing E, Connolly M, Lindsay D, Garvey G. Wellbeing of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, Aotearoa (New Zealand) and the United States: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(11):5832. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115832

Chicago/Turabian StyleGall, Alana, Kate Anderson, Kirsten Howard, Abbey Diaz, Alexandra King, Esther Willing, Michele Connolly, Daniel Lindsay, and Gail Garvey. 2021. "Wellbeing of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, Aotearoa (New Zealand) and the United States: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 11: 5832. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115832

APA StyleGall, A., Anderson, K., Howard, K., Diaz, A., King, A., Willing, E., Connolly, M., Lindsay, D., & Garvey, G. (2021). Wellbeing of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, Aotearoa (New Zealand) and the United States: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 5832. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115832