“Give Us the Chance to Be Part of You, We Want Our Voices to Be Heard”: Assistive Technology as a Mediator of Participation in (Formal and Informal) Citizenship Activities for Persons with Disabilities Who Are Slum Dwellers in Freetown, Sierra Leone

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Context

“We, the disability community of SL, call on political parties to invest in… the inclusion and participation of PWDs in the political process”[33]

“’Citizen’ and ‘citizenship’ are powerful words. They speak of respect, rights and dignity…[with] no pejorative uses” [35] …yet, although the “idea of citizenship is nearly universal…what it means and how it is experienced, is not”(ibid., p. 1)

Ethics (Context)

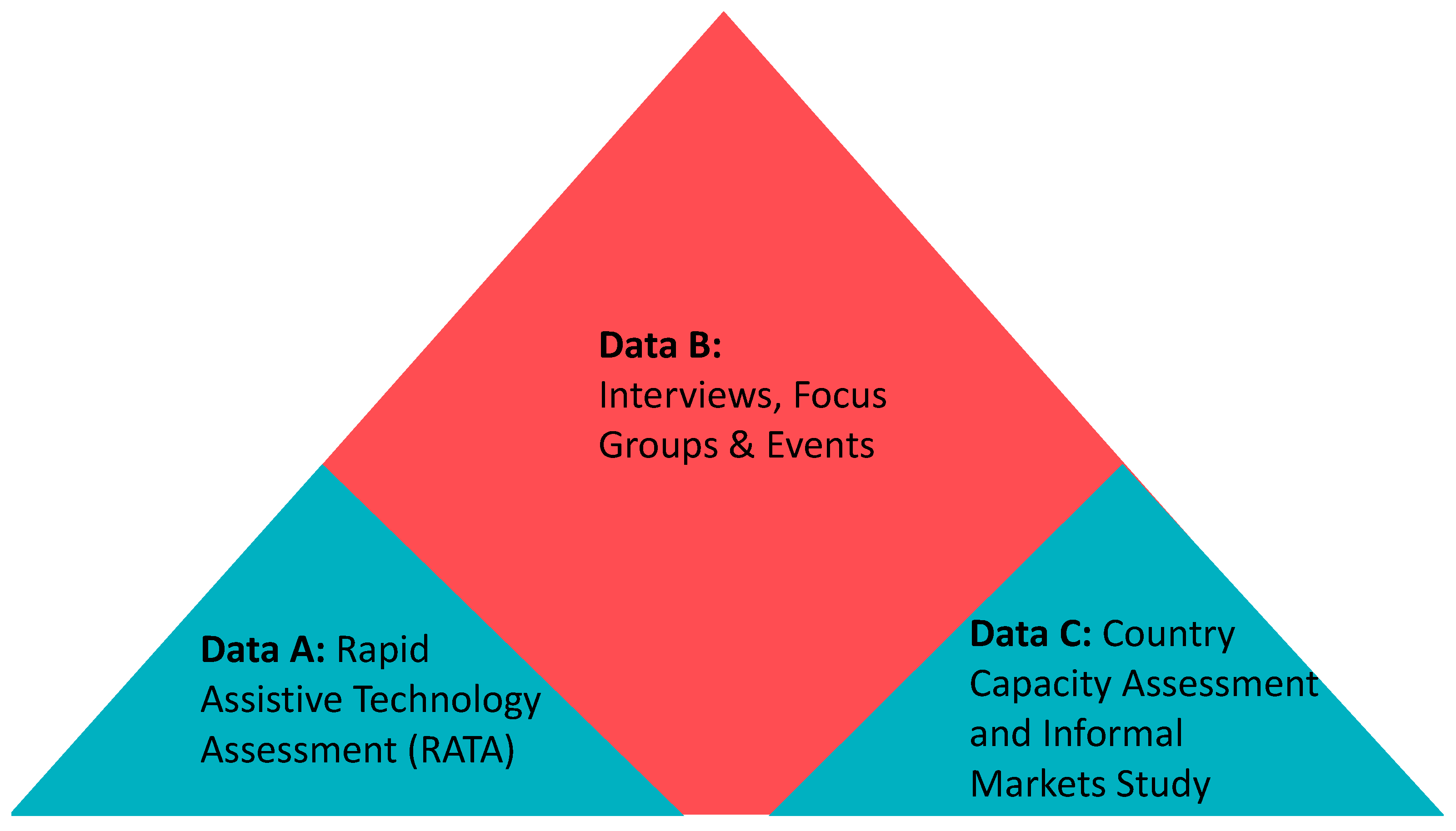

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Setting

3.1.1. Study Location

3.1.2. The Policy Context in SL

3.2. Study Design

- Is participation in the (formal and informal) activities of citizenship valued by persons with disabilities who slum-dwellers in Freetown, Sierra Leone?

- What level of access to AT does this group have?

- How does AT, or lack thereof, mediate (formal and informal) citizenship participation?

- What recommendations can this offer to the formulation of policy and practice?

3.3. Research Team and Reflexivity

3.4. Participant Selection and Data Collection

3.4.1. Study A: Rapid Assistive Technology Assessment Survey

3.4.2. Study B: Direct, Detailed Inputs from Participants and Stakeholders

Semi Structured Interviews with Participants

Interview Guide for Participant Interviews

Semi-Structured Interviews with Stakeholders

Focus Group Discussions

Events

Transcription, Translation and Consent

3.4.3. Study C: Country Capacity Assessments

Formal Country Capacity Assessment

Informal Markets Study

3.5. Data Analysis and Reporting

4. Results

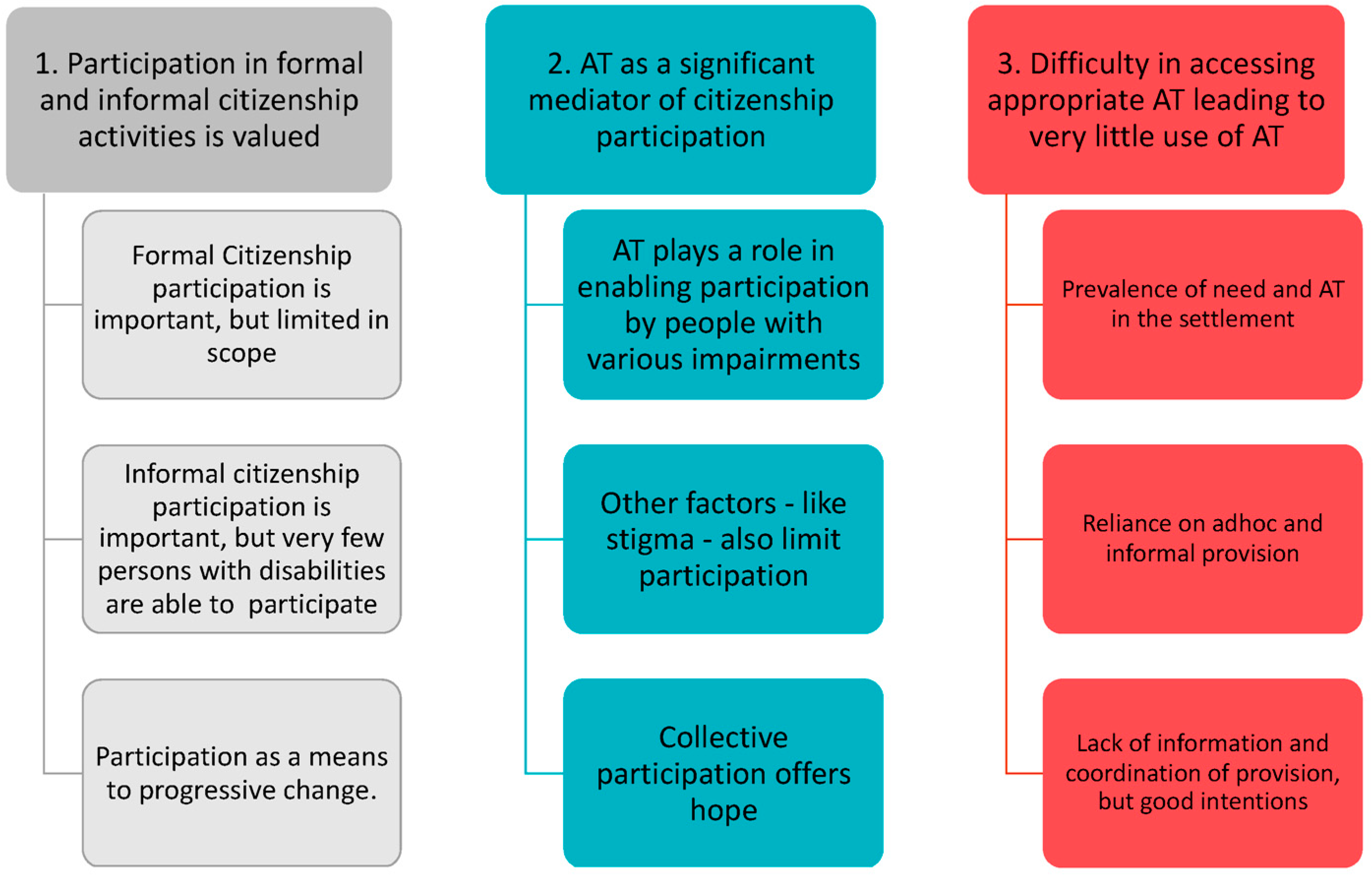

4.1. Thematic Framework

4.2. Participatoin in Formal and Informal Citizenship Activities Is Valued by Persons with Disabilities Who Live in the Settlements

4.2.1. Formal Citizenship Is an Important ‘Right’ but Limited in Scope in Practice

“I was born here and raised here, had my 8 children here and they attended school in SL, I am so happy to be a Sierra Leonean.”(Woman, D-03)

“I vote every election, I have to exercise my right to vote because it is my right.”(Woman, D-03)

“…at the end of the day the election comes and they promise and then nothing is done. During the election they drive me and then I never see them again.”(Woman, D-04)

“Disabled people are not allowed to do things, I was told I wasn’t allowed to staff a ballot box… and I was not too ok with that, because I wanted to do it.”(Woman, TB-01)

“…we are expected to keep our environment clean, to pay taxes and to …make the land become peaceful.”(Man, D-05)

“I have a big position in the Scouts…so I use scouting procedure and the community people…know me, that I am…helping the community…. [for example] every cleaning [day] I organize my boys to clear.”(Man, TB-08)

“…the government should provide for our necessities because we are citizens of Sierra Leone.”(Man, TB-07)

“[As a citizen] I should receive my education, glasses for my eyes and cream for my skin [for albinism].”(Woman, D-02)

“We are expecting good schools, good toilets, good bridges, and a good road for the community benefit…”(Man, TB-03)

“…in the Disability Act…. but it doesn’t happen. So, when you go to medical (people) you have to pay. They request you to pay…. We are not getting some of the facilities we are expecting as citizens of SL.”(Man, Dworzark)

4.2.2. Informal Citizenship Is Valued but Few Persons with Disabilities Participate

“I’d advise them [to] abide by the law, involve yourself in the community activities and clean.”(Woman, TB-01)

“The community meeting is only for men and also stakeholders in the community.”(Woman, TB-05)

“It is also important [to feeling a part of the community] to give financially, physically and morally to the development of the community.”(Man, TB-07)

“We do not have the opportunity to discuss our issues as disabled people in these meetings…they only consider the non-disabled.”(Man, TB-02)

“Firstly, we can go to the Chief because he is the head of the community…. we should go ‘to the big one’ [Chief]…When we want to discuss these issues, we should have unity among us [persons with disabilities] so that we will later channel these issues to the stakeholder in the community, call them into community meeting, but there is no unity.”(Man, D-01)

“I think that the reason we are not meeting together is so as not to show ourselves to the community...most of these people believe that disabled people always cause trouble...that is their knowledge.”(Man, TB-08)

4.2.3. Participation as a Means to Progressive Change

“I think that we should come together to sensitize ourselves on what we should know as disableds [sic] having one common goal. Our expectations should not be always high, but rather to advocate for support … with some AT like, wheelchair, crutches and other supporting equipment as disables, and to see how we can better our lives with this assistance.”(Man, TB-06)

“It will be good for disabled people to organize and come together and form a group because in that group you will be say the challenges you are going through, some of the struggles, be able to explain to others and other are able to proffer a solution to those challenges. By those discussions also you will be able to inform exciting opportunities that are available elsewhere.”(Man, D-05)

“Well if we come together…the first thing we… need is water…so if we come together as one, we work with the stakeholder in the community, we bring to other people, we bring everything together and move for water, pipes and material to come here... and make the point. As soon as water is available in the community that is the number one way [to gain respect] because the number one thing that the community does want is done by the disabled (sic).”(Man, TB-08)

4.3. Mediators of Participation in Citizenship Activities

4.3.1. AT as Mediator of Participation

“[Community membership] is not the same [for disabled people], because like for instance, I am having difficulty to walk, so if they call for any meeting that has to do with development, I cannot be able to attend or participate in that meeting, except I send my daughter to attend, because I am having mobility issue, so those that are the non-disabled are the ones that can be involved in the process.”(Man, TB-06)

“I am not able to walk (unaided) now... …but if I were younger, I would be making bold steps, I would mobilize people.”(Woman, D-04)

“I have to stay home most of the time…you can’t use the public toilets; you can’t walk around, and no space is easy.”(Woman, TB-01)

“[Interviewer: why don’t you go to community meetings, where you say decisions are made?]. Because of physical barriers and challenges.”(Woman, D-07)

“We don’t find it difficult to accept disabled people. Whether you are disabled or not, in slum community or informal settlements you are faced with 90% the same issues. Except … there are some issues that disabled people face that able people don’t face.”(Man, stakeholder participant)

“It is not the same [for persons with disabilities], because like, for instance, I am having difficulty to walk, so if they call for any meeting that has to do with development, I cannot be able to attend or participate so those that are the non-disabled are the ones that can be involved in the process.”(Man, TB-06)

“I can tell the people with no disability that they should be listening to us as disabled, because as humans we know the starting of our lives, but we don’t know our end, there is a possibility that one day the able might also become disabled, so I say give us the chance to be part of you, and for our voices to be heard.”(Man, TB-07)

4.3.2. Stigma and Discrimination Also Limited Participation

“In this community, the non-disabled are many and the disabled we are few and they are not seeing us as useful people. We are considered ‘less’ in this community.”(Man, TB-06)

“So, you can go around [to meetings, etc.] but you choose not to because of the stigmatizations you get from people.”(Man, D-01)

“There are children who usually call me ‘cut hand’.(Man, D-08)

“[When I had to have my leg amputation] at the Government hospital they gossiped, they said, “this girl may die, and that’s ok”. I was so depressed and sad and I couldn’t keep myself calm…. the non-disabled people should stop mocking the disabled people in this community because of their condition.”(Woman, TB-1)

“We are not equal in terms of rights, because being disabled, sometimes people take advantage of us...when you have a matter in the police—someone reported you or takes something to the police station—your rights or voice as a disabled person cannot be heard.”(Man, D-06)

“I find it very difficult for me to have something to eat, but with all the support of the community I am ok because they help me out...the community people do respect me as an elder person in the community.”(Man, TB-04)

“Their (SLUDI) offices are very far away… the last meeting I went to [in 2014] I told them that I wanted to be part of their organisations. They took my name, but they never called me... They never came here but if they did, they could sensitize the community and explain the usefulness of disabled people. So, I’m sure that if SLUDI start coming here and do some sensitization, the community will see that all the people that are part of SLUDI are (useful) disabled people.”(Man, TB-08)

4.3.3. A Desire for Collective Participation to Drive Change

“...awareness of disability is developing, for instance, we had a grant about gender equality and social inclusion in informal settlements to ensure that women and disabled people were included in terms of household and community decision making...the aspect of disability became very strong and that’s why we found out that we can partner with SLUDI to develop the UNDP programme [which has just been funded].”(Man, stakeholder interviewee)

“Before [AT2030] I was ashamed of my visual impairment, but since this project has started, I now have the courage to speak, express myself and move around the community.”(Participant at Disability Celebration Day, TB)

“Me too, I was ashamed to walk in certain areas within the community, but now is better.”(Woman, TB-01)

“I think the challenge is that Disabled People are in slums, but it’s difficult to identify them. That’s why we are very much pleased with the AT project. This has been the first time we have been able to work with disabled people in a community. It has been very more difficult for us in our (previous) mobilisations…”(Man, stakeholder participant)

“This is the first time of celebrating this day especially at community level which has been a remarkable day and this has created the space to feel belonging and make new friends and knowing that disability is not inability [one of the event slogans].”(Participant at Celebration Day event, Dworzark)

“This is our home and we can show how much we are capable of doing. Just because you are small you can still participate.”(Woman, TB-03)

4.4. Difficulty in Accessing Appropriate AT, Leading to Very Little Use

4.4.1. Prevalence of AT Need and Availability

rATA Survey

- 52 pairs of spectacles (representing 81% of total APs)

- 3 axillary or elbow crutches

- 1 manual wheelchair

- 1 rollator and walking frame

- 1 therapeutic footwear

First-Hand Accounts of Participants

“when we went to the hospital the price of my AT was very expensive.”(Woman, D-03)

“My parents bought me a crutch…but was very expensive (150,000 leones, about £13)…and it has a snapped armrest…it costs about 30,000 Leones (£2.50) to replace the rubber feet….Without my crutches, I couldn’t go anywhere.”(Young Female, TB-01)

“I got my leg in 2007, I think it came from France.”(Man, D-05)

“In the morning my son moves me from my bed to outside my home [shack structure] under the tree, sitting in the [broken, static] wheelchair. I am more comfortable sitting there because it has a lot of wind blowing and shade, so it helps me a lot. After 7:00 pm, my son takes me back into my bedroom.”(Man, TB-4)

“We always hear on the news that there are things coming for us…but we only get the news….”(Man, TB-08)

“You hear these things like wheelchairs have arrived for the disabled (sic)’... but when you go to the office…they never say when they are going to distribute them.”(Man TB-8)

“You go to the hospital and you will have to buy everything...when the money finish they will discharge you whether you get better or not…. If you have the medicine but not the needle, they will not attend to you.”(Woman, D-02)

“I have seen so many people that didn’t have a helper pass away.”(Woman, D-03)

“I used to be a farmer...and after the farming year I would come with some gifts for the community…now I am blind but… [the young people]... they read the chapter of the Bible for me and I interpret it for them.”(Man, TB-03)

4.4.2. Reliance on Ad Hoc and Informal Provision

“The government is not helping us. In the past, at the place at Aberdeen (informal shop) the AT was not much expensive, but now it is very much expensive to buy the AT products.”(Man, D-01)

“I only hear through rumour, from friends and others, some usually said where they bought their AP”(Man, D-08)

It costs about 30,000 (£2.50) to replace the rubber feet [for the crutches] from the market.(Woman, TB-01)

4.4.3. There Was a Lack of Information and Coordination at Provision at National Level

5. Discussion

5.1. Research Discussion

5.2. Limitations and Further Research

5.3. Reflections Offered to Policy and Practice

- A greater degree of nuance is needed in the global evidence base on AT to address the specific issues of persons with disabilities who live in informal settlements—often this is the poorest group who are most in need yet research about the lived experience of this group, and their voices, are infrequently heard.

- AT as an enabler of citizenship participation deserves a greater understanding to avoid a de-facto and reductive focus on economically productive activities such as learning and earning. This will require more investigation into the ‘ends’ AT users define as valued, for which AT provides the ‘means’.

- In building a plan for comprehensive AT access, the Government of Sierra Leone could be helpfully supported through international co-operation as per the CRPD; particular attention might be paid to the informal market, given its prevalence. Supporting informal market traders appropriately and continuing to engage with slum dwellers with disabilities and their communities as coordination and investment are prioritized, will be important.

- Further research into AT as a mediator of participation parity (understood here as a model of disability justice) could be considered. Citizenship should be tested further as the lens for this exploration.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Topic Guide—Data A

Appendix A.1. Intro

- AT2030—consent and recording

- Reminder of research objectives

Appendix A.2. Part 1: Initial Questions

- Name

- Age

- Gender

- Occupation/Education

- Where do you live and with whom?

- For how long have you lived in this community?

- What AT do you have and use (triangulate with RATA)?

Appendix A.3. Part 2: Key Lines of Enquiry

- (1)

- Can you describe what it means to you to be a Sierra Leonean—to be a citizen of SL?

- (a)

- What are the basic things a citizen of SL can expect?

- (b)

- What are the basic things a citizen of SL must do?

- (2)

- What activities do you do, as citizen of Sierra Leone?

- (a)

- Do you need, or receive, any help in these activities e.g., from friends/family or assistive technology?

- (b)

- Are there any activities you would like to do but cannot?

- (3)

- Do you think there are any differences for a disabled person in being a citizen of SL, compared to a non-disabled person?

- (4)

- What makes someone be considered as a community member in this settlement?(Prompts: norms, meetings, development projects, community revenue contribution—is it more than just residency?)

- (a)

- If committees/meetings—Are you involved in any community meetings? Do you attend? Does anyone ever raise disability issues?

- (b)

- Are you a member of any other groups in the community e.g., church/mosque/social?

- (5)

- Are there any differences in the the things a disabled person will be required to do to be considered a community member?

- (6)

- Are there any ways that disabled people are able to participate with other disabled people in the settlement? (e.g., groups for disabled people, meetings or informal activities)

- (a)

- If no…do you think its would be god to have this type of meeting? Or not necessary?

- (b)

- Why?

- (7)

- If someone wanted to raise issues of concern to disabled people in the settlement how would they do that?

- (8)

- If you had the opportunity to raise issues that are important to disabled people, here what are the top issues you would raise with the community/community leaders (or other people identified in 7)?

- (9)

- Can you tell me about whether /how things have changed in terms of participation for disabled people in the community throughout the time you have lived here?

- (10)

- Where is it that you feel people listen to you and your voice is heard? (e.g., home, school, community, social media?)

- (11)

- Where do you feel most able to be yourself? (translation: to be ‘comfortable’ and ‘feel fine’)

Appendix A.4. Part 3: End Questions

- Is there anything else you’d like to tell me?

- Is there anyone else you think I should talk to?

- Is there anything else you’d like to ask about the research?

Appendix B. Data Ca CCA Stakeholder Survey List

- Directorate of NCDs and Mental Health, MOHS

- National Assistive Technology Programme, MOHS

- Ministry of Social Welfare Gender and Children’s Affairs (MSWGCA)

- National Commission for Persons with Disability

- Sierra Leone Union on Disability Issues

- POPDA Makeni

- WESOFORD Kambia

- Mobility Sierra Leone Bo

- Handicap International

- SLEDT

- 34 Military Hospital

- MoHS/Sierra Leone Physiotherapy Association (SLPA)

- MoHS/Sierra Leone Orthotic & Prosthetic Association (SLOPA)

- MoHS/NRC

- MoHS Connaught

- MoHS BO Government Hospital

- Koidu Regional Rehabilitation Center Koidu Govt Hospital

- Emergency Hospital

- MoHS BO Government Hospital

- World Health Organisation

- Abdul Miracle Disabled Children’s Foundation

- Sierra Leone Association of the Deaf

- Human Rights Commission Sierra Leone

- Ministry of Education

- Freetown Chercher Home

- Disability Awareness Action Group

- Amputee/War Wounded

- One Family People Org. Freetown

- Kings SL Partnership

- Enable the Children

- Latter Day Saint

- NEHP/MoHS

- Life Matters Disabled Foundation

- Sierra Leone Urban Research Center

Appendix C

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 (Added) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Status of DP in Community | Shame/Sense of Belonging | Expectations of Citizenship | Active Citizenship Practices | (Lack of) Collective Participation on Disability or by DP | AT Provision and Need |

| Begging | Asking for help | Aspirations/hopes | Community collective participation | Disability and citizenship in reality | AT need |

| Helping to gain respect | Discrimination/mockery | AT provision (moved to 6) | membership of the community | ODP and representation | AT provision |

| Status in the community (combining age, gender and owner/tenant) | (lack of) Recognition | Broken promises | How to make change | Political Participation | Informal provision |

| Self-perception mindset | Common community issues | Reliance on community action | National capacity | ||

| Sense of belonging | Expectations | Tackling disability issues in the city | AT ‘for what’? | ||

| Shame | Media/culture |

References

- WHO|Priority Assistive Products List (APL). Available online: http://www.who.int/phi/implementation/assistive_technology/global_survey-apl/en/ (accessed on 25 October 2016).

- World Health Organization Assitive Technology, Fact Sheet. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/assistive-technology/en/ (accessed on 3 July 2017).

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) |United Nations Enable. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html (accessed on 5 June 2018).

- Tebbutt, E.; Brodmann, R.; Borg, J.; MacLachlan, M.; Khasnabis, C.; Horvath, R. Assistive products and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Glob. Health 2016, 12, 79. Available online: http://globalizationandhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12992-016-0220-6 (accessed on 11 November 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ATScale. The Case for Investing in Assistive Technology; ATscale: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Holloway, C.; Austin, V.; Barbareschi, G.; Ramos Barajas, F.; Pannell, L.; Morgado Ramirez, D.; Frost, R.; McKinnon, I.; Holmes, C.; Frazer, R.; et al. Scoping Research Report on Assistive Technology; On the Road to Universal Assistive Technology Coverage, UCL: London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.disabilityinnovation.com/uploads/images/AT-Scoping-Report_2019-compressed-19.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2020).

- Barbareschi, G.; Holloway, C.; Arnold, K.; Magomere, G.; Wetende, W.A.; Ngare, G.; Olenja, J. The social network: How people with visual impairment use mobile phones in kibera, Kenya. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Online, 25–30 April 2020; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- MacLachlan, M.; McVeigh, J.; Cooke, M.; Ferri, D.; Holloway, C.; Austin, V.; Javadi, D. Intersections Between Systems Thinking and Market Shaping for Assistive Technology: The SMART (Systems-Market for Assistive and Related Technologies) Thinking Matrix. Int. J. Env. Res. Public. Health 2018, 15, 2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Layton, N.; MacLachlan, M.; Smith, R.O.; Scherer, M. Towards coherence across global initiatives in assistive technology. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2020, 15, 728–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faccioli, S.; Lombardi, F.; Bellini, P.; Costi, S.; Sassi, S.; Pesci, M.C. How Did Italian Adolescents with Disability and Parents Deal with the COVID-19 Emergency? Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, E.M.; Toro Hernandez, M.L.; Ebuenyi, I.D.; Syurina, E.V.; Barbareschi, G.; Best, K.L.; Danemayer, J.; Oldfrey, B.; Ibrahim, N.; Holloway, C.; et al. Assistive Technology Use and Provision during COVID-19: Results from a Rapid Global Survey. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.; MacLachlan, M.; Ebuenyi, I.D.; Holloway, C.; Austin, V. Developing Inclusive and Resilient Systems: COVID-19 and Assistive Technology. Disabil. Soc. 2021, 36, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.; Sallam, N.; Sesay, S.; Gandi, I. Country Capacity Assessment for Assistive Technologies: Informal Markets Study, Sierra Leone; AT2030 Working Paper Series. 2020. Available online: https://at2030.org/country-capacity-assessment-for-assistive-technologies:-informal-markets-study,-sierra-leone/ (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M.C. Frontiers of Justice: Disability, Nationality, Species Membership; Belknap: Cambridge, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-0-674-01917-1. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, S. The Capability Approach and Disability. J. Disabil. Policy Stud. 2006, 16, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robeyns, I. The Capability Approach in Practice*. J. Polit. Philos. 2006, 14, 351–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, P. Collective capabilities, culture, and Amartya Sen’sDevelopment as Freedom. Stud. Comp. Int. Dev. 2002, 37, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, V.S. Understanding Disability in Theory, Justice, and Planning. In Building the Inclusive City: Governance, Access, and the Urban Transformation of Dubai; Pineda, V.S., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 23–45. ISBN 978-3-030-32988-4. [Google Scholar]

- Huchzermeyer, M. Troubling Continuities; Routledge Handbooks: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-0-415-81865-0. [Google Scholar]

- Habitat III, The New Urban Agenda. Available online: http://habitat3.org/the-new-urban-agenda/ (accessed on 23 September 2017).

- Macarthy, J.M.; Koroma, B. Framing the Research Agenda and Capacity Building Needs for Equitable Urban Development in Freetown; SLURC Publication: Freetown, Sierra Leone, 2016; ISBN 978-0-9956342-0-6. Available online: http://www.slurc.org/uploads/1/6/9/1/16915440/slurc_report.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- Braithwaite, J.; Mont, D. Disability and poverty: A survey of World Bank Poverty Assessments and implications. ALTER Eur. J. Disabil. Res. Rev. Eur. Rech. Sur Handicap 2009, 3, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbareschi, G.; Oldfrey, B.; Xin, L.; Magomere, G.N.; Wetende, W.A.; Wanjira, C.; Olenja, J.; Austin, V.; Holloway, C. Bridging the Divide: Exploring the use of digital and physical technology to aid mobility impaired people living in an informal settlement. In Proceedings of the 22nd International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (ASSETS ’20); Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, M.M.; Jahan, N.; Nahar, L. Low assistive technologies for persons with spinal cord injury (SCI) in Bangladesh. World Fed. Occup. Ther. Bull. 2014, 69, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sackey, E. Disability and political participation in Ghana: an alternative perspective. Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 2015, 17, 366–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, M.; Mprah, W.; Saka, B. Participation of persons with disabilities in political activities in Cameroon. Disabil. Glob. South 2017, 3, 980–999. [Google Scholar]

- Rahahleh, Z.J.; Hyassat, M.A.; Khalaf, A.; Sabayleh, O.A.; Al-Awamleh, R.A.K.; Alrahamneh, A.A. Participation of Individuals with Disabilities in Political Activities: Voices from Jordan. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2021, 29, 329–347. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Assistive Technology Assessment (ATA) Toolkit. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/ata-toolkit (accessed on 16 May 2021).

- Nossal Institute for Global Health. A Manual for Implementing the Rapid Assistive Technology Assessment; Nossal Institute for Global Health: Melbourne, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- WHO|World Report on Disability. Available online: https://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/report/en/ (accessed on 23 January 2019).

- Walsh, S.; Johnson, O. Getting to Zero: A Doctor and a Diplomat on the Ebola Frontline; Zed Books: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-78699-247-5. [Google Scholar]

- Persons with Disabilities Agenda; SLUDI: Freetown, SL, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.wfd.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/PWD-Agenda.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2019).

- Dagnino, E. Citizenship: A Perverse Confluence. Dev. Pract. 2007, 17, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. Introduction: The search for inclusive citizenship: Meanings and expressions in an interconnected world. In Inclusive Citizenship: Meanings and Expressions; Kabeer, I.N., Ed.; Zed: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Green, D. How Change Happens; University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Green, D. From Poverty to Power: How Active Citizens and Effective States Can Change the World, Pap/Cdr ed.; Fried, M., Ed.; Oxfam Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-0-85598-593-6. [Google Scholar]

- Appadurai, A. The Capacity to Aspire: Culture and the Terms of Recognition. In Cult. and Public Action; Vijayenra, R., Walton, M., Eds.; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 59–84. [Google Scholar]

- Appadurai, A. Deep democracy: urban governmentality and the horizon of politics. Environ. Urban. 2001, 13, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monson, T.J. Collective mobilization and the struggle for squatter citizenship: Rereading “xenophobic” violence in a South African settlement. Int. J. Confl. Violence 2015, 9, 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- Shakespeare, T. Disability Rights and Wrongs Revisited, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-0-415-52761-3. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Sierra Leone 2015 Population and Housing Census Summary of Final Results Planning a Better Future 2016. Available online: https://www.statistics.sl/index.php/census/census-2015.html (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Sierra Leone’s Medium Term Development Plan, 2019–2023, Govt of SL, 2019, Freetown SL. Available online: https://www.slurc.org/uploads/1/0/9/7/109761391/sierra_leone_national_development_plan.pdf. (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- Transform Freetown, An Overview 2019–2022, Freetown City Council, Freetown Sierra Leone. Available online: https://fcc.gov.sl/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Transform-Freetown-an-overview.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Marx, C.; Kelling, E. Knowing urban informalities. Urban Stud. 2019, 56, 494–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, S. Producing and contesting the formal/informal divide: Regulating street hawking in Delhi, India. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 2596–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julian, W.; Braima, K.; Sudie, A.S.; Andrea, R. The social regulation of livelihoods in unplanned settlements in Freetown: implications for strategies of formalisation. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Goodley, D. Towards socially just pedagogies: Deleuzoguattarian critical disability studies. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2007, 11, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KoBoToolbox|Data Collection Tools for Challenging Environments. Available online: https://kobotoolbox.org/ (accessed on 16 May 2021).

- RATA Toolkit and Training. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2021/02/08/default-calendar/who-online-master-training-workshop-for-measuring-access-to-assistive-technology (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Tomlinson, R. The Scalability of the Shack/Slum Dwellers International Methodology: Context and Constraint in Cape Town. Dev. Policy Review 2017, 35, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodley, D. Dis/entangling critical disability studies. Disabil. Soc. 2013, 28, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafer, A. Feminist, Queer, Crip; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-253-00941-8. [Google Scholar]

- Pineda, V.S. What Makes a City Accessible and Inclusive. In Building the Inclusive City: Governance, Access, and the Urban Transformation of Dubai; Pineda, V.S., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-32988-4. [Google Scholar]

- Parette, P.; Scherer, M. Assistive Technology Use and Stigma. Educ. Train. Dev. Disabil. 2004, 39, 217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Brakel, W.H.V. Measuring health-related stigma—A literature review. Psychol. Health Med. 2006, 11, 307–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, N. Rethinking Recognition. Available online: https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii3/articles/nancy-fraser-rethinking-recognition. (accessed on 3 May 2000).

- Khasnabis, C.; Holloway, C.; MacLachlan, M. The Digital and Assistive Technologies for Ageing initiative: Learning from the GATE initiative. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2020, 1, e94–e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COREQ (Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies)-Guidelines for Reporting Health Research: A User’s Manual-Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781118715598.ch21 (accessed on 22 April 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Austin, V.; Holloway, C.; Ossul Vermehren, I.; Dumbuya, A.; Barbareschi, G.; Walker, J. “Give Us the Chance to Be Part of You, We Want Our Voices to Be Heard”: Assistive Technology as a Mediator of Participation in (Formal and Informal) Citizenship Activities for Persons with Disabilities Who Are Slum Dwellers in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5547. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115547

Austin V, Holloway C, Ossul Vermehren I, Dumbuya A, Barbareschi G, Walker J. “Give Us the Chance to Be Part of You, We Want Our Voices to Be Heard”: Assistive Technology as a Mediator of Participation in (Formal and Informal) Citizenship Activities for Persons with Disabilities Who Are Slum Dwellers in Freetown, Sierra Leone. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(11):5547. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115547

Chicago/Turabian StyleAustin, Victoria, Cathy Holloway, Ignacia Ossul Vermehren, Abs Dumbuya, Giulia Barbareschi, and Julian Walker. 2021. "“Give Us the Chance to Be Part of You, We Want Our Voices to Be Heard”: Assistive Technology as a Mediator of Participation in (Formal and Informal) Citizenship Activities for Persons with Disabilities Who Are Slum Dwellers in Freetown, Sierra Leone" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 11: 5547. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115547

APA StyleAustin, V., Holloway, C., Ossul Vermehren, I., Dumbuya, A., Barbareschi, G., & Walker, J. (2021). “Give Us the Chance to Be Part of You, We Want Our Voices to Be Heard”: Assistive Technology as a Mediator of Participation in (Formal and Informal) Citizenship Activities for Persons with Disabilities Who Are Slum Dwellers in Freetown, Sierra Leone. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 5547. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115547