Mistreatment from Multiple Sources: Interaction Effects of Abusive Supervision, Coworker Incivility, and Customer Incivility on Work Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

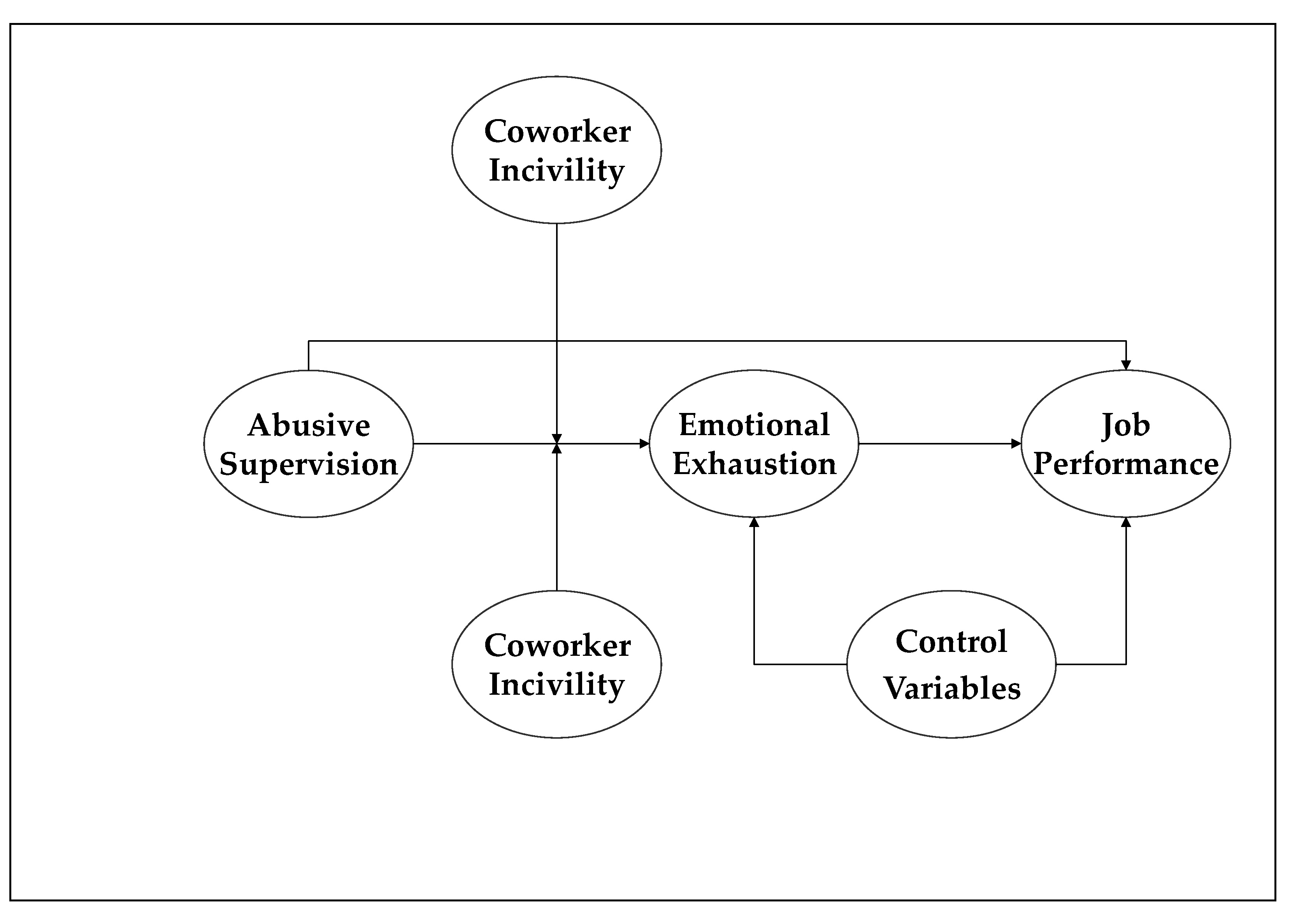

2.1. Mediating Relationship between Abusive Supervision, Emotional Exhaustion, and Job Performance

2.2. Moderating Effects of Coworker and Customer Incivility on the Abusive Supervision–Emotional Exhaustion Relationship

2.3. Moderating Effects of Coworker and Customer Incivility on the Abusive Supervision–Emotional Exhaustion–Job Performance Relationahip

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Test of Reliability, Validity, and Common Method Variance

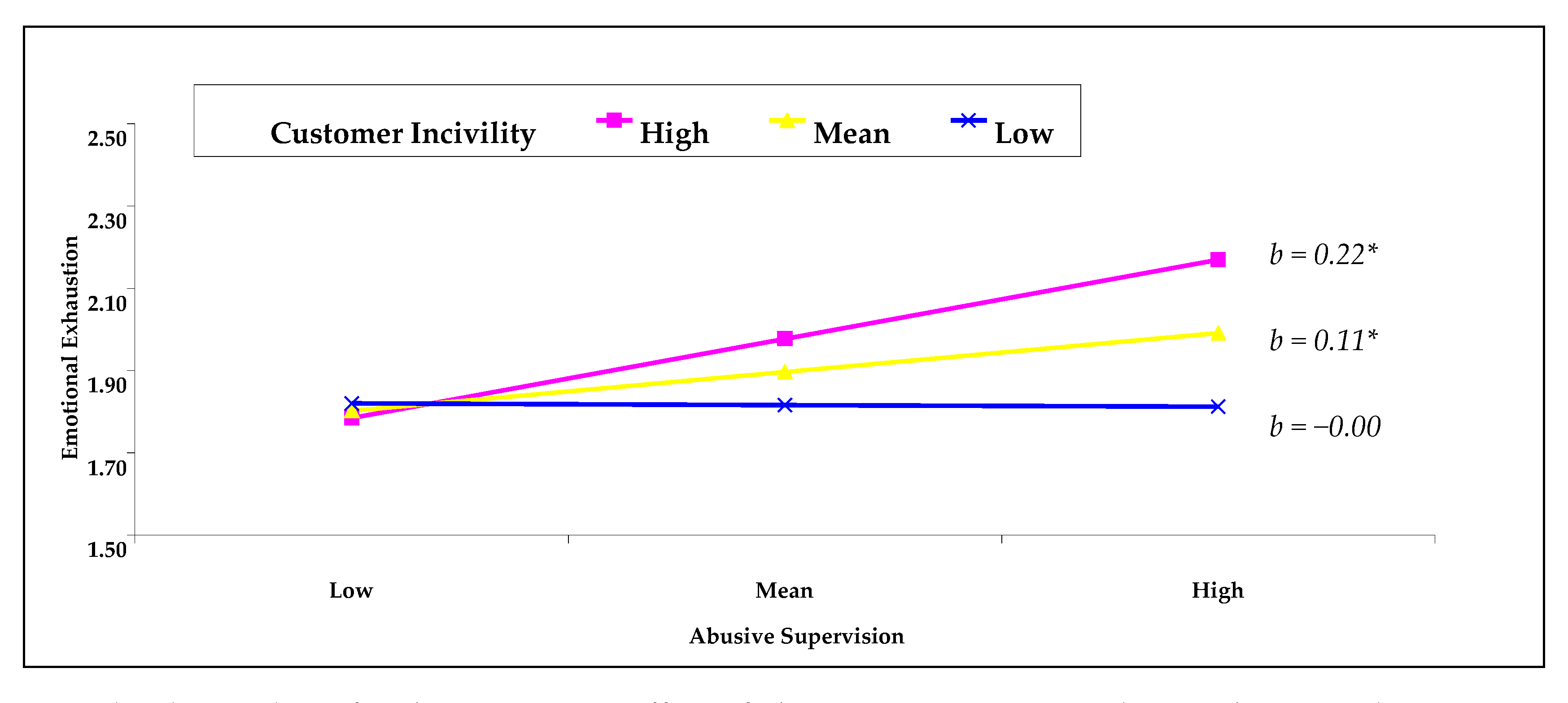

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

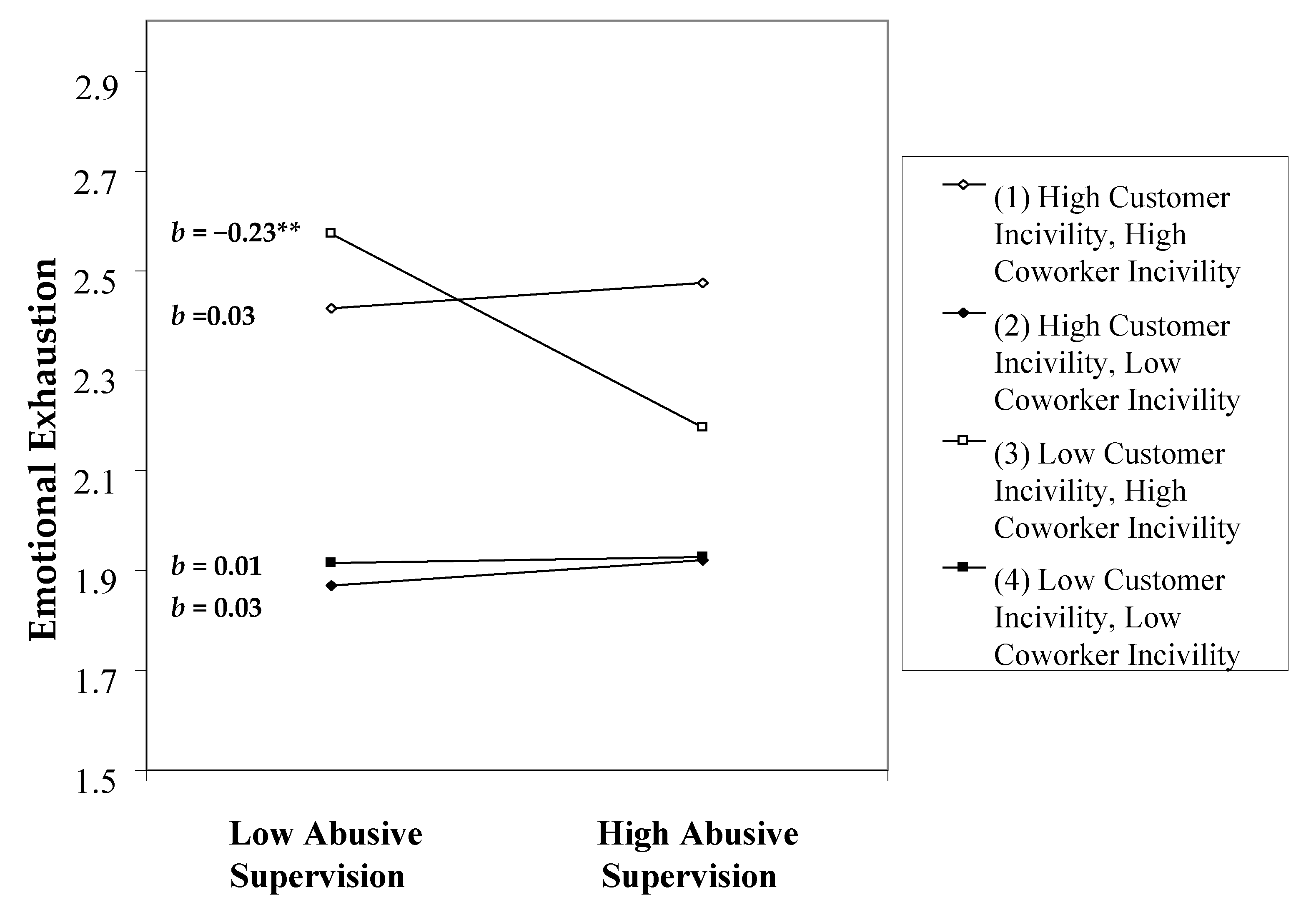

4.3. Post Hoc Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Study Limitations and Directions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Hawari, M.A.; Bani-Melhem, S.; Quratulain, S. Do frontline employees cope effectively with abusive supervision and customer incivility? Testing the effect of employee resilience. J. Bus. Psychol. 2020, 35, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasli, H.; Namin, B.H.; Abubakar, A.M. Workplace incivility as a moderator of the relationships between polychronicity and job outcomes. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1245–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.; Bonn, M.A.; Han, S.J.; Lee, K.H. Workplace incivility and its effect upon restaurant frontline service employee emotions and service performance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 2888–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.J.; Bonn, M.A.; Cho, M. The relationship between customer incivility, restaurant frontline service employee burnout and turnover intention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 52, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliter, M.; Sliter, K.; Jex, S. The employee as a punching bag: The effect of multiple sources of incivility on employee withdrawal behavior and sales performance. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilpzand, P.; De Pater, I.E.; Erez, A. Workplace incivility: A review of the literature and agenda for future research. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, S57–S88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Z.; Kwan, H.K.; Qiu, Q.; Liu, Z.Q.; Yim, F.H. Abusive supervision and frontline employees’ service performance. Serv. Ind. J. 2012, 32, 683–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Xu, S.; Li, G.; Kong, H. A systematic review of research on abusive supervision in hospitality and tourism. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2473–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, K.A.; Walsh, M.M. Customer incivility and employee well-being: Testing the moderating effects of meaning, perspective taking, and transformational leadership. Work Stress 2015, 29, 362–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani-Melhem, S. What mitigate and exacerbate the influence of customer incivility on frontline employee extra-credit behavior? J. Hosp. Tour Manag. 2020, 44, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani-Melhem, S.; Quratulain, S.; Al-Hawari, M.A. Customer incivility and frontline employees’ revenge intentions: Interaction effects of employee empowerment and turnover intentions. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukis, A.; Koritos, C.; Daunt, K.L.; Papastathopoulos, A. Effects of customer incivility on frontline employees and the moderating role of supervisor leadership style. Tour. Manag. 2020, 77, 103997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Dong, Y.; Zhou, X.; Guo, G.; Peng, Y. Does customer incivility undermine employees’ service performance? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 89, 102544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, S.; Sun, L.; Chen, Z.X.G.; Debrah, Y.A. Abusive supervision and contextual performance: The mediating role of emotional exhaustion and the moderating role of work unit structure. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2008, 4, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, B.J. Consequences of abusive supervision. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 178–190. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, L.M.; Pearson, C.M. Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 452–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glomb, T.M. Workplace anger and aggression: Informing conceptual models with data from specific encounters. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2002, 7, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, M.M.; Barling, J. Understanding the many faces of workplace violence. In Counterproductive Work Behavior: Investigations of Actors and Targets; Fox, S., Spector, P.E., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 41–63. [Google Scholar]

- Cortina, L.M.; Magley, V.J.; Williams, J.H.; Langhout, R.D. Incivility in the workplace: Incidence and impact. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2001, 6, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, J.K.; Sud, K. Exploring influence mechanism of abusive supervision on subordinates’ work incivility: A proposed framework. Bus. Perspec. Res. 2021, 9, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J.; Anderson, S.E. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S. The measurement of experienced burnout. J. Organ. Behav. 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Hur, W. Supervisor incivility and employee job performance: The mediating roles of job insecurity and amotivation. J. Psychol. 2020, 154, 38–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenbaum, R.L.; Quade, M.J.; Mawritz, M.B.; Kim, J.; Crosby, D. When the customer is unethical: The explanatory role of employee emotional exhaustion onto work-family conflict, relationship conflict with coworkers, and job neglect. J. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 99, 1188–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y.; Lee, E.J.; Hur, W. Supervisor incivility, job insecurity, and service performance among flight attendants: The buffering role of coworker support. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommovigo, V.; Setti, I.; Argentero, P. The role of service providers’ resilience in buffering the negative effect of customer incivility on service recovery performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Rupp, D.E.; Byrne, Z.S. The relationship of emotional exhaustion to work attitudes, job performance, and organizational citizenship behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.; Bowler, W.M. Organizational citizenship behaviors and burnout. In A Handbook on Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Review of “Good Solder” Activity in Organizations; Turnipseed, D.L., Ed.; Nova Science: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 399–414. [Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben, J.R.; Bowler, W.M. Emotional exhaustion and job performance: The mediating role of motivation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, M.K.; Ganster, D.C.; Pagon, M. Social undermining in the workplace. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 331–351. [Google Scholar]

- Miner, K.N.; Settles, I.H.; Pratt-Hyatt, J.S.; Brady, C.C. Experiencing incivility in organizations: The buffering effects of emotional and organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 42, 340–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Martinez, L.R.; Hoof, H.V.; Tews, M.; Torres, L.; Farfan, K. The impact of abusive supervision and coworker support on hospitality and tourism student employees’ turnover intentions in Ecuador. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teas, R.K. Supervisory behavior, role stress, and the job satisfaction of industrial salespeople. J. Mark. Res. 1983, 20, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tittlebach, D.; Deangelis, M.; Sturmey, P.; Alvero, A.M. The effects of task clarification, feedback, and goal setting on student advisors’ office behaviors and customer service. J. Organ. Behav. Manag. 2007, 27, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, N.; Yang, J.; Lin, C. Service workers’ chain reactions to daily customer mistreatment: Behavioral linkages, mechanisms, and boundary conditions. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 58–70. [Google Scholar]

- Grandey, A.A.; Diamond, J.A. Interactions with the public: Bridging job design and emotional labor perspectives. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliter, M.; Jex, S.; Wolford, K.; McInnerney, J. How rude! Emotional labor as a mediator between customer incivility and employee outcomes. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 468–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, R.N.; Behrend, T.S. An inconvenient truth: Arbitrary distinctions between organizational, Mechanical Turk, and other convenience samples. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 8, 142–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulin, N. Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater: Comparing data quality of crowdsourcing, online panels, and student samples. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 8, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N.L.; Holmvall, C.M. The development and validation of the Incivility from Customers Scale. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 310–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, T.W.; Hur, W.M.; Hyun, S.S. How service employees’ work motivations lead to job performance: The role of service employees’ job creativity and customer orientation. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 38, 517–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, S.Y.; Hur, W.M.; Kim, M. The relationship of coworker incivility to job performance and the moderating role of self-efficacy and compassion at work: The Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) approach. J. Bus. Psychol. 2017, 32, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Hur, W.M. When do service employees suffer more from job insecurity? The moderating role of coworker and customer incivility. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y.; Hur, W.M.; Moon, T.W.; Lee, S. A motivational perspective on job insecurity: Relationships between job insecurity, intrinsic motivation, and performance and behavioral outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Hur, W.M.; Choi, W.H. Coworker support as a double-edged sword: A moderated mediation model of job crafting, work engagement, and job performance. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 1417–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E. Development and validation of an internationally reliable short-form of the positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS). J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2007, 38, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. Psychometric Theory; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.; MacKenzie, S.; Podsakoff, N. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.; West, S. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.H.; Ono, M. Effects of workplace bullying on work engagement and health: The mediating role of job insecurity. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 3202–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, J.D.; Frieder, R.E.; Brees, J.R.; Martinko, M.J. Abusive supervision: A meta-analysis and empirical review. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1940–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Liao, Z. Consequences of abusive supervision: A meta-analytic review. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2015, 32, 959–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliter, M.; Pui, S.Y.; Sliter, K.; Jex, S. The differential effects of interpersonal conflict from customers and coworkers: Trait anger as a moderator. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 424–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, C.M.; Porath, C.L. On the nature, consequences, and remedies of workplace incivility: No time for “nice”? Think again. Acad. Manag. Exec. 2005, 19, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Kim, S. Customer mistreatment harms nightly sleep and next-morning recovery: Job control and recovery self-efficacy as cross-level moderators. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 256––269. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.N.; Zhang, M.J.; Law, K.S.; Yan, M.N. Subordinate performance and abusive supervision: The role of envy and anger. In Academy of Management Meeting Proceedings; Academy of Management: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2015; p. 16420. [Google Scholar]

| Construct | Measurement Items | λ (c) |

|---|---|---|

| Abusive supervision (a) | My supervisor makes negative comments about me to others. | 0.78 |

| My supervisor gives me the silent treatment. | 0.84 | |

| My supervisor expresses anger at me when he/she is mad for another reason. | 0.88 | |

| My supervisor is rude to me. | 0.85 | |

| My supervisor breaks promises he/she makes. | 0.85 | |

| My supervisor puts me down in front of others. | 0.83 | |

| Coworker incivility (b) | How often do coworkers ignore or exclude you while at work? | 0.84 |

| How often do coworkers raise their voices at you while at work? | 0.79 | |

| How often are coworkers rude to you at work? | 0.92 | |

| How often do coworkers do demeaning things to you at work? | 0.83 | |

| Customer incivility (b) | How often have customers… | |

| …continued to complain despite your efforts to assist them? | 0.75 | |

| …made gestures (e.g., eye rolling, sighing) to express their impatience? | 0.74 | |

| …grumbled to you about slow service during busy times? | 0.87 | |

| …made negative remarks to you about your organization? | 0.82 | |

| …blamed you for a problem you did not cause? | 0.82 | |

| …used an inappropriate manner of addressing you (e.g., “Hey, you”)? | 0.73 | |

| …failed to acknowledge your efforts when you have gone out of your way to help them? | 0.83 | |

| …grumbled to you that there were too few employees working? | 0.79 | |

| …complained to you about the value of goods and services? | 0.80 | |

| …made inappropriate gestures to get your attention (e.g., snapping fingers)? | 0.73 | |

| Emotional exhaustion (a) | I feel frustrated with my job. | 0.56 |

| I feel used up at the end of the workday. | 0.79 | |

| I feel like I am working too hard in my job. | 0.87 | |

| I feel like I am at the end of my rope. | 0.81 | |

| Job performance (a) | I adequately complete assigned duties. | 0.84 |

| I fulfill the responsibilities specified in my job description. | 0.89 | |

| I perform the tasks that are expected of me. | 0.80 | |

| I meet the formal performance requirements of my job. | 0.81 | |

| Positive affectivity (a) | Determined | 0.79 |

| Attentive | 0.83 | |

| Alert | 0.86 | |

| Inspired | 0.82 | |

| Active | 0.67 | |

| Negative affectivity (a) | Afraid | 0.78 |

| Nervous | 0.82 | |

| Upset | 0.86 | |

| Ashamed | 0.82 | |

| Hostile | 0.64 | |

| χ2(644) = 1845.61; p < 0.05, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.04 | ||

| Variables | M | SD | α | CR | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 0.36 | 0.48 | - | - | - | 1 | |||||||||

| 2. Age | 35.69 | 8.51 | - | - | - | −0.12 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| 3. Job tenure | 4.68 | 4.21 | - | - | - | 0.04 | 0.39 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 4. Positive affectivity | 2.51 | 0.84 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.64 | 0.13 ** | 0.06 | −0.10 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 5. Negative affectivity | 2.96 | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.68 | −0.11 ** | −0.22 ** | −0.02 | 0.30 ** | 1 | |||||

| 6. Abusive supervision | 2.09 | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.70 | 0.10 * | −0.06 | −0.00 | −0.12 ** | 0.28 ** | 1 | ||||

| 7. Coworker incivility | 2.01 | 0.87 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.76 | 0.10 ** | 0.06 | 0.05 | −0.08 * | 0.24 ** | 0.56 ** | 1 | |||

| 8. Customer incivility | 2.62 | 0.84 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.62 | −0.12 ** | −0.21 ** | 0.04 | −0.23 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.28 ** | 1 | ||

| 9. Emotional exhaustion | 2.21 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.59 | 0.09 * | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.21 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.23 ** | 1 | |

| 10. Job performance | 3.92 | 0.65 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.70 | −0.12 ** | −0.06 | −0.09 * | 0.22 ** | −0.08 † | −0.16 ** | −0.24 ** | −0.08 * | −0.47 ** | 1 |

| Path | Effect (b) | 95% CIlow | 95% CIhigh |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Effect | |||

| Abusive supervision→Job performance | −0.089 | −0.145 | −0.032 |

| Direct Effect | |||

| Abusive supervision→Job performance | −0.037 | −0.089 | 0.014 |

| Indirect Effect | |||

| Abusive supervision→Emotional exhaustion→Job performance | −0.052 | −0.084 | −0.022 |

| Variables | Emotional Exhaustion | Job Performance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | (se) | b | (se) | |

| Gender | 0.16 | (0.06) ** | −0.10 | (0.05) * |

| Age | −0.00 | (0.04) | −0.00 | (0.00) |

| Job tenure | −0.01 | (0.08) | −0.01 | (0.01) |

| Positive affectivity | −0.15 | (0.04) ** | 0.12 | (0.03) ** |

| Negative affectivity | 0.13 | (0.04) ** | 0.06 | (0.03) * |

| Abusive supervision | −0.04 | (0.04) | −0.04 | (0.03) |

| Coworker incivility | 0.32 | (0.04) ** | ||

| Customer incivility | 0.06 | (0.04) | ||

| Abusive supervision × Coworker incivility | −0.04 | (0.03) | ||

| Abusive supervision × Customer incivility | 0.13 | (0.04) ** | ||

| Emotional exhaustion | −0.34 | (0.03) ** | ||

| R2 | 22.3% | 25.4% | ||

| Moderated mediation index | ||||

| Abusive supervision × Coworker incivility→Emotional exhaustion→Job performance: b = 0.014, 95% CI = [−0.021, 0.045] | ||||

| Abusive supervision × Customer incivility→Emotional exhaustion→Job performance: b = −0.044, 95% CI = [−0.076, −0.010] | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shin, Y.; Hur, W.-M.; Kang, S. Mistreatment from Multiple Sources: Interaction Effects of Abusive Supervision, Coworker Incivility, and Customer Incivility on Work Outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5377. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105377

Shin Y, Hur W-M, Kang S. Mistreatment from Multiple Sources: Interaction Effects of Abusive Supervision, Coworker Incivility, and Customer Incivility on Work Outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(10):5377. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105377

Chicago/Turabian StyleShin, Yuhyung, Won-Moo Hur, and Seongho Kang. 2021. "Mistreatment from Multiple Sources: Interaction Effects of Abusive Supervision, Coworker Incivility, and Customer Incivility on Work Outcomes" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 10: 5377. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105377

APA StyleShin, Y., Hur, W.-M., & Kang, S. (2021). Mistreatment from Multiple Sources: Interaction Effects of Abusive Supervision, Coworker Incivility, and Customer Incivility on Work Outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(10), 5377. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105377