The Homestead: Developing a Conceptual Framework through Co-Creation for Innovating Long-Term Dementia Care Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

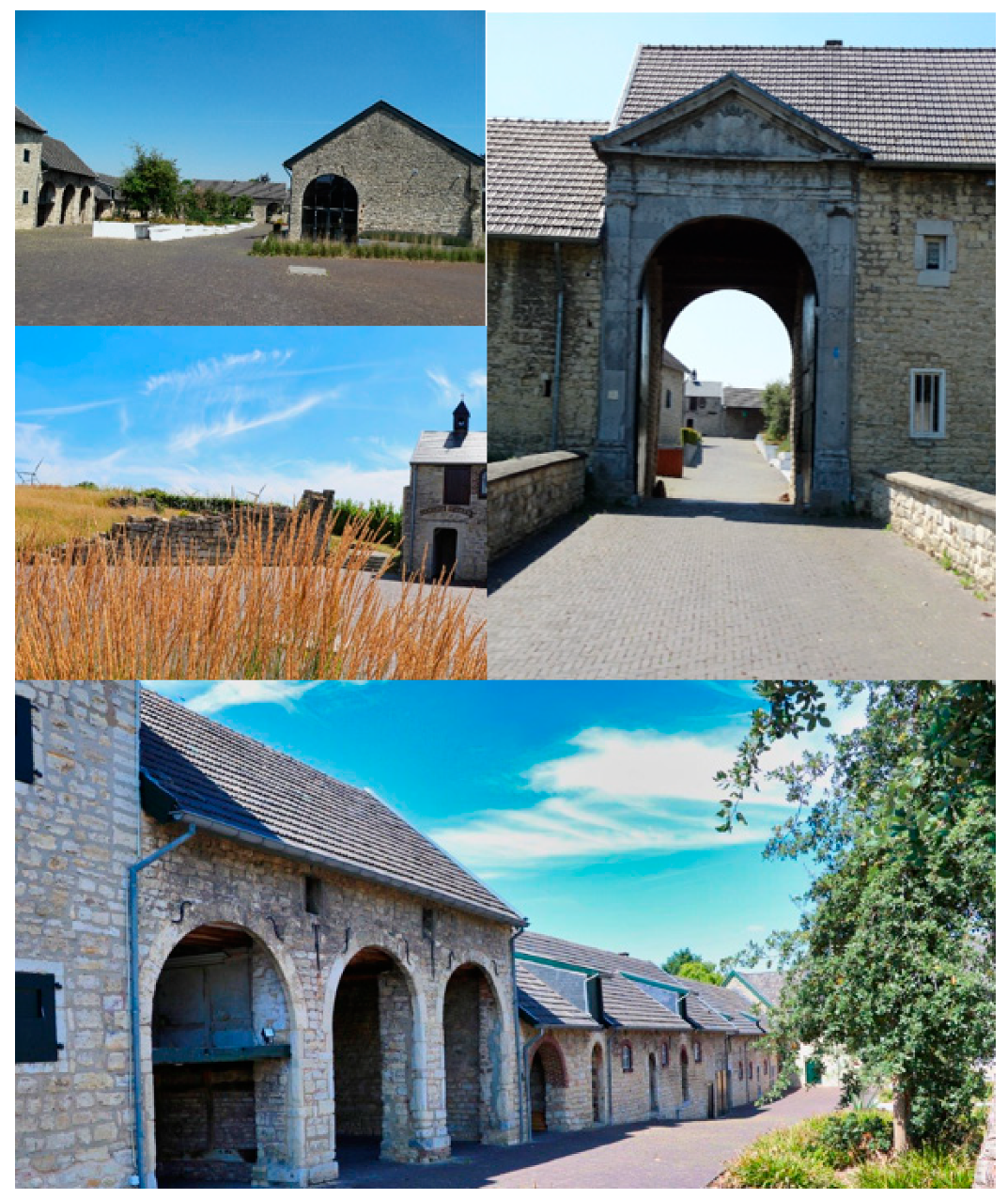

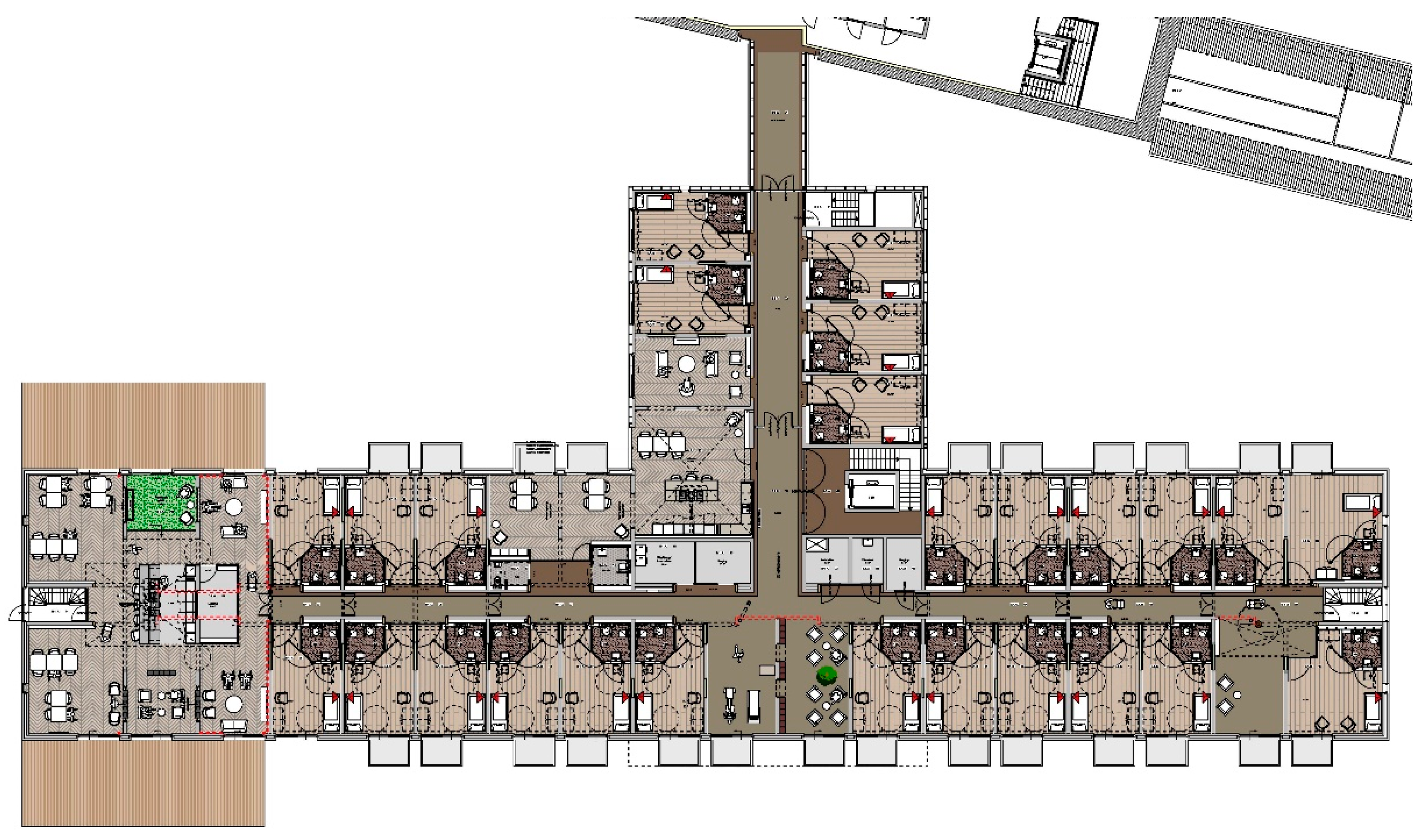

2.2. Case and Context Description

2.3. Participants

- Resident, family and community engagement working groups: these working groups focused on engaging residents, family and people or organizations in the community in the development of the care model. Again, these took different forms ranging from large meetings with over 50 clubs and organizations from the local community, to smaller gatherings with family members and possible future residents. Besides standard gatherings, this working group also organized an official opening of the Homestead, informing the local community about the planning and concept of the Homestead. This opening was attended by more than 500 residents from the village. This working group also informed the community by sending multiple information letters regarding the state of affairs.

- Staff working groups: these working groups took several different forms during the development process ranging from brainstorm sessions with large groups of care staff (e.g., all staff of the original traditional nursing home of the village), and smaller gatherings of care staff focusing on e.g., describing what a day of a resident should look like in the Homestead, how to incorporate the outside areas more, etc. Thus, these groups varied from 3 to 30 staff members (including direct care staff, registered nurses from home-care teams, social workers and case manager).

- Technology working group (n = 6): this working group consisted of a nursing home manager, an innovation manager, an information advisor, care staff, ICT staff and a researcher from the university. This working group focused on all relevant technological questions and issues in order to facilitate providing care according to the care model such as home automation, beacon technology, etc.

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Collection and Analyses

3. Results

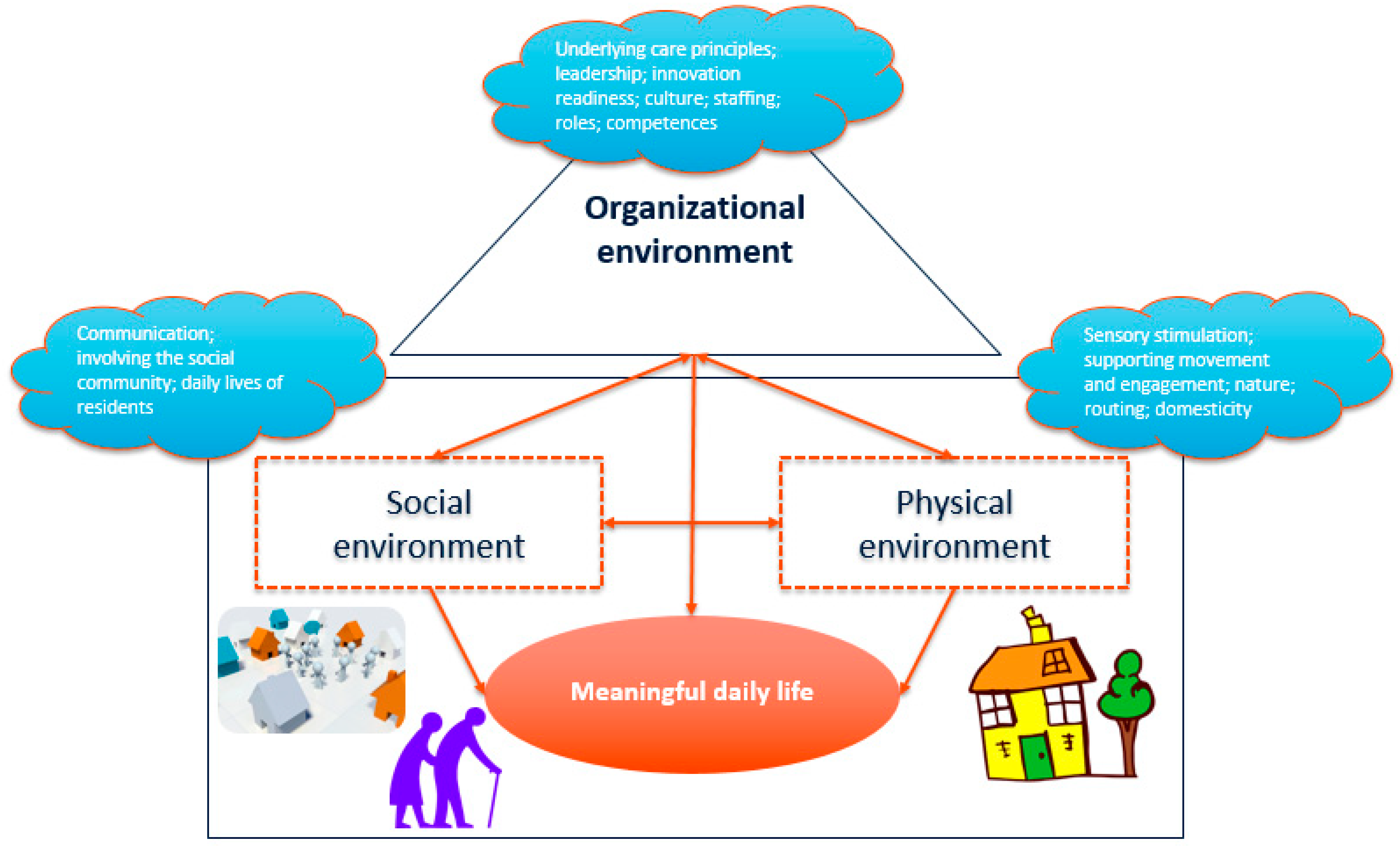

3.1. Theoretical Framework

- Physical aspects, including interior design, outdoor areas (e.g., gardens), architecture, built environment, lay-out aspects and sensory elements.

- Social aspects, including interactions with others in the environment. This includes resident, staff, family and friends and also the wider community and social context in which a dementia care setting is situated (e.g., local entrepreneurs, societies, and schools).

- Organizational aspects, including the way dementia care is organized and how the organizational culture is being perceived (e.g., values, expectations, attitudes that guide behavior of staff working in the dementia care setting).

3.2. Translation into Practice: The Homestead Care Model

3.2.1. The Physical Environment

3.2.2. The Social Environment

3.2.3. The Organizational Environment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wiersma, E.C.; Pedlar, A. The nature of relationships in alternative dementia care environments. Can. J. Aging 2008, 27, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Boer, B.; Beerens, H.C.L.; Katterbach, M.A.; Viduka, M.; Willemse, B.M.; Verbeek, H. The physical environment of nursing homes for people with dementia: Traditional nursing homes, small-scale living facilities, and green care farms. Healthcare 2018, 6, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topo, P.; Kotilainen, H.; Eloniemi-Sulkava, U. Affordances of the care environment for people with dementia—An assessment study. HERD 2012, 5, 118–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- den Ouden, M.; Bleijlevens, M.H.C.; Meijers, J.M.M.; Zwakhalen, S.M.G.; Braun, S.M.; Tan, F.E.S.; Hamers, J.P.H. Daily (in) activities of nursing home residents in their wards: An observation study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 963–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donovan, C.; Donovan, A.; Stewart, C.; McCloskey, R. How residents spend their time in nursing homes. Can. Nurs. Home 2014, 25, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wetzels, R.B.; Zuidema, S.U.; de Jonghe, J.F.M.; Verhey, F.R.J.; Koopmans, R.T.C.M. Course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in residents with dementia in nursing homes over 2-year period. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2010, 18, 1054–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helvik, A.S.; Selbaek, G.; Saltyte Benth, J.; Roen, I.; Bergh, S. The course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in nursing home residents from admission to 30-month follow-up. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206147. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, K.; Kwan, J.S.; Kwan, C.W.; Chong, A.M.; Lai, C.K.; Lou, V.W.; Leung, A.Y.; Liu, J.Y.; Bai, X.; Chi, I. Factors associated with the trend of physical and chemical restraint use among long-term care facility residents in Hong Kong: Data from an 11-year observational study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 1043–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.R.; Simões, M.R.; Moreira, E.; Guedes, J.; Fernandes, L. Modifiable factors associated with neuropsychiatric symptoms in nursing homes: The impact of unmet needs and psychotropic drugs. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 86, 103919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausserhofer, D.; Deschodt, M.; De Geest, S.; van Achterberg, T.; Meyer, G.; Verbeek, H.; Sjetne, I.S.; Malinowska-Lipien, I.; Griffiths, P.; Schluter, W.; et al. “There’s No Place Like Home”: A scoping review on the impact of homelike residential care models on resident-, family-, and staff-related outcomes. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2016, 17, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, M.J. Person-centered care for nursing home residents: The culture-change movement. Health Aff. 2010, 29, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbeek, H.; Van Rossum, E.; Zwakhalen, S.M.G.; Kempen, G.I.; Hamers, J.P.H. Small, homelike care environments for older people with dementia: A literature review. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2009, 21, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charras, K.; Eynard, C.; Viatour, G. Use of space and human rights: Planning dementia friendly settings. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2016, 59, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, R.; Zeisel, J.; Bennet, K. World Alzheimer Report 2020: Design, Dignity, Dementia: Dementia-Related Design and the Built Environment; Alzheimer’s Disease International: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhury, H.; Cooke, H.A.; Cowie, H.; Razaghi, L. The influence of the physical environment on residents with dementia in long-term care settings: A review of the empirical literature. Gerontologist 2018, 58, e325–e337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhury, H.; Cooke, H. Design matters in dementia care: The role of the physical environment in dementia care settings. Excell. Dement. Care 2014, 2, 144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Jao, Y.-L.; Liu, W.; Chaudhury, H.; Parajuli, J.; Holmes, S.; Galik, E. Function-Focused Person-Environment Fit for Long-Term Care Residents with Dementia: Impact on Apathy. Gerontologist 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.; Leland, N.E. Applying the Person-Environment-Occupation Model to Improve Dementia Care; OT Practice: London, UK, 2018; pp. CE-1–CE-7. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, S. Space, choice and control, and quality of life in care settings for older people. Environ. Behav. 2006, 38, 589–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, R.; Goodenough, B.; Low, L.-F.; Chenoweth, L.; Brodaty, H. The relationship between the quality of the built environment and the quality of life of people with dementia in residential care. Dementia 2016, 15, 663–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, R.; Zeisel, J.; Bennet, K. World Alzheimer Report 2020: Design Dignity Dementia: Dementia-Related Design and the Built Environment Volume 2: Case Studies; Alzheimer’s Disease International: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- De Bruin, S.R.; Oosting, S.; van der Zijpp, A.; Enders-Slegers, M.-J.; Schols, J. The concept of green care farms for older people with dementia: An integrative framework. Dementia 2010, 9, 79–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruin, S.R.; Stoop, A.; Molema, C.C.; Vaandrager, L.; Hop, P.J.; Baan, C.A. Green care farms: An innovative type of adult day service to stimulate social participation of people with dementia. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2015, 1, 2333721415607833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassink, J.; Van Dijk, M. Farming for Health: Green-Care Farming across Europe and the United States of America; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin, S.R.; de Boer, B.; Beerens, H.C.; Buist, Y.; Verbeek, H. Rethinking dementia care: The value of green care farming. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buist, Y.; Verbeek, H.; de Boer, B.; de Bruin, S.R. Innovating dementia care; implementing characteristics of green care farms in other long-term care settings. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2018, 30, 1057–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Boer, B.; Hamers, J.P.H.; Zwakhalen, S.M.G.; Tan, F.E.S.; Beerens, H.C.; Verbeek, H. Green care farms as innovative nursing homes, promoting activities and social interaction for people with dementia. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerens, H.C.; Zwakhalen, S.M.G.; Verbeek, H.; Tan, F.E.S.; Jolani, S.; Downs, M.; de Boer, B.; Ruwaard, D.; Hamers, J.P.H. The relation between mood, activity, and interaction in long-term dementia care. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Boer, B.; Hamers, J.P.H.; Zwakhalen, S.M.G.; Tan, F.E.S.; Verbeek, H. Quality of care and quality of life of people with dementia living at green care farms: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingsen-Dalskau, L.H.; de Boer, B.; Pedersen, I. Comparing the care environment at farm-based and regular day care for people with dementia in Norway—An observational study. Health Soc. Care Community 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.W.; Zimmerman, S.; Reed, D.; Brown, P.; Bowers, B.J.; Nolet, K.; Sandra Hudak, R.N.; Horn, S.D. The Green House Model of Nursing Home Care in Design and Implementation. Health Serv. Res. 2016, 51, 352–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voorberg, W.H.; Bekkers, V.J.J.M.; Tummers, L.G. A Systematic Review of Co-Creation and Co-Production: Embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 1333–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergdahl, E.; Ternestedt, B.M.; Bertero, C.; Andershed, B. The theory of a co-creative process in advanced palliative home care nursing encounters: A qualitative deductive approach over time. Nurs. Open 2019, 6, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verleye, K.; Jaakkola, E.; Hodgkinson, I.R.; Jun, G.T.; Odekerken-Schroder, G.; Quist, J. What causes imbalance in complex service networks? Evidence from a public health service. J. Serv. Manag. 2017, 28, 34–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luijkx, K.; van Boekel, L.; Janssen, M.; Verbiest, M.; Stoop, A. The Academic Collaborative Center Older Adults: A Description of Co-Creation between Science, Care Practice and Education with the Aim to Contribute to Person-Centered Care for Older Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbeek, H.; Zwakhalen, S.M.G.; Schols, J.M.; Kempen, G.I.; Hamers, J.P.H. The Living Lab in Ageing and Long-Term Care: A Sustainable Model for Translational Research Improving Quality of Life, Quality of Care and Quality of Work. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2020, 24, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charras, K.; Bébin, C.; Laulier, V.; Mabire, J.-B.; Aquino, J.-P. Designing dementia-friendly gardens: A workshop for landscape architects: Innovative Practice. Dementia 2018, 2018, 1471301218808609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edvardsson, D. Therapeutic environments for older adults: Constituents and meanings. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2008, 34, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawton, M.P.; Nahemow, L. Ecology and the Aging Process. 1973. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2004-15428-020 (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Low, L.-F.; Draper, B.; Brodaty, H. The relationship between self-destructive behaviour and nursing home environment. Aging Ment. Health 2004, 8, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torrington, J. What has architecture got to do with dementia care? Explorations of the relationship between quality of life and building design in two EQUAL projects. Qual. Ageing 2006, 7, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whear, R.; Coon, J.T.; Bethel, A.; Abbott, R.; Stein, K.; Garside, R. What is the impact of using outdoor spaces such as gardens on the physical and mental well-being of those with dementia? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2014, 15, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.; Byers, S.; Nay, R.; Koch, S. Guiding design of dementia friendly environments in residential care settings: Considering the living experiences. Dementia 2009, 8, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodbridge, R.; Sullivan, M.; Harding, E.; Crutch, S.; Gilhooly, K.; Gilhooly, M. Use of the physical environment to support everyday activities for people with dementia: A systematic review. Dementia 2018, 17, 533–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhury, H.; Hung, L.; Badger, M. The role of physical environment in supporting person-centered dining in long-term care: A review of the literature. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Dement. 2013, 28, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, R.; Crookes, P.A.; Sum, S. A Review of the Empirical Literature on the Design of Physical Environments for People with Dementia. 2008. Available online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3923&context=hbspapers (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Day, K.; Carreon, D.; Stump, C. The therapeutic design of environments for people with dementia: A review of the empirical research. Gerontologist 2000, 40, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijkstra, K.; Pieterse, M.; Pruyn, A. Physical environmental stimuli that turn healthcare facilities into healing environments through psychologically mediated effects: Systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 56, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquardt, G. Wayfinding for people with dementia: A review of the role of architectural design. HERD 2011, 4, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, R.; Weisbeck, C. Creating a supportive environment using cues for wayfinding in dementia. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2016, 42, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenoweth, L.; Forbes, I.; Fleming, R.; King, M.; Stein-Parbury, J.; Luscombe, G.; Kenny, P.; Jeon, Y.-H.; Haas, M.; Brodaty, H. PerCEN: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial of Person-Centered Residential Care and Environment for People with Dementia. 2014. Available online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2827&context=smhpapers (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Davis, R.; Ohman, J.M.; Weisbeck, C. Salient cues and wayfinding in Alzheimer’s disease within a virtual senior residence. Environ. Behav. 2017, 49, 1038–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douma, J.G.; Volkers, K.M.; Engels, G.; Sonneveld, M.H.; Goossens, R.H.; Scherder, E.J. Setting-related influences on physical inactivity of older adults in residential care settings: A review. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Berg, M.E.; Winsal, M.; Dyer, S.M.; Breen, F.; Gresham, M.; Crotty, M. Understanding the Barriers and Enablers to Using Outdoor Spaces in Nursing Homes: A Systematic Review. Gerontologist 2020, 60, e254–e269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charras, K.; Zeisel, J.; Belmin, J.; Drunat, O.; Sebbagh, M.; Gridel, G.; Bahon, F. Effect of personalization of private spaces in special care units on institutionalized elderly with dementia of the Alzheimer type. Non-Pharmacol. Ther. Dement. 2010, 1, 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoof, J.; Janssen, M.L.; Heesakkers, C.M.C.; Van Kersbergen, W.; Severijns, L.E.J.; Willems, L.A.G.; Marston, H.R.; Janssen, B.M.; Nieboer, M.E. The importance of personal possessions for the development of a sense of home of nursing home residents. J. Hous. Elder. 2016, 30, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinney, A.; Chaudhury, H.; O’connor, D.L. Doing as much as I can do: The meaning of activity for people with dementia. Aging Ment. Health 2007, 11, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernooij-Dassen, M. Meaningful Activities for People with Dementia; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, T.; Gardiner, P. Communication and interaction within dementia care triads: Developing a theory for relationship-centred care. Dementia 2005, 4, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, B.; McCance, T.V. Development of a framework for person-centred nursing. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 56, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilberforce, M.; Batten, E.; Challis, D.; Davies, L.; Kelly, M.P.; Roberts, C. The patient experience in community mental health services for older people: A concept mapping approach to support the development of a new quality measure. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilberforce, M.; Challis, D.; Davies, L.; Kelly, M.P.; Roberts, C. The preliminary measurement properties of the person-centred community care inventory (PERCCI). Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 2745–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, C. The organisational culture of nursing staff providing long-term dementia care is related to quality of care. Evid. Based Nurs. 2011, 14, 88–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, B.; Sjøvold, E.; Rannestad, T.; Ringdal, G.I. The impact of work culture on quality of care in nursing homes—A review study. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2014, 28, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etherton-Beer, C.; Venturato, L.; Horner, B. Organisational culture in residential aged care facilities: A cross-sectional observational study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvardsson, D.; Fetherstonhaugh, D.; McAuliffe, L.; Nay, R.; Chenco, C. Job satisfaction amongst aged care staff: Exploring the influence of person-centered care provision. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2011, 23, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backman, A.; Ahnlund, P.; Sjögren, K.; Lövheim, H.; McGilton, K.S.; Edvardsson, D. Embodying person-centred being and doing: Leading towards person-centred care in nursing homes as narrated by managers. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvardsson, D.; Sandman, P.-O.; Nay, R.; Karlsson, S. Associations between the working characteristics of nursing staff and the prevalence of behavioral symptoms in people with dementia in residential care. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2008, 20, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beek, A.; Gerritsen, D. The relationship between organizational culture of nursing staff and quality of care for residents with dementia: Questionnaire surveys and systematic observations in nursing homes. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 1274–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Liu, F.; Murfield, J.; Moyle, W. Effects of non-facilitated meaningful activities for people with dementia in long-term care facilities: A systematic review. Geriatr. Nurs. 2020, 41, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, A.; Radel, J.; McDowd, J.M.; Sabata, D. Perspectives of people with dementia about meaningful activities: A synthesis. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Dement. 2016, 31, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyman, S.R.; Szymczynska, P. Meaningful activities for improving the wellbeing of people with dementia: Beyond mere pleasure to meeting fundamental psychological needs. Perspect. Public Health 2016, 136, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Travers, C.; Brooks, D.; Hines, S.; O’Reilly, M.; McMaster, M.; He, W.; MacAndrew, M.; Fielding, E.; Karlsson, L.; Beattie, E. Effectiveness of meaningful occupation interventions for people living with dementia in residential aged care: A systematic review. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2016, 14, 163–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beerens, H.C.; De Boer, B.; Zwakhalen, S.M.G.; Tan, F.E.S.; Ruwaard, D.; Hamers, J.P.H.; Verbeek, H. The association between aspects of daily life and quality of life of people with dementia living in long-term care facilities: A momentary assessment study. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2016, 28, 1323–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistridis, P.; Mata, J.; Neuner-Jehle, S.; Annoni, J.M.; Biedermann, A.; Bopp-Kistler, I.; Brand, D.; Brioschi Guevara, A.; Decrey-Wick, H.; Démonet, J.F.; et al. Use it or lose it! Cognitive activity as a protec-tive factor for cognitive decline associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2017, 147, w14407. [Google Scholar]

- Fielding, R.A.; Guralnik, J.M.; King, A.C.; Pahor, M.; McDermott, M.M.; Tudor-Locke, C.; Manini, T.M.; Glynn, N.W.; Marsh, A.P.; Axtell, R.S.; et al. Dose of physical activity, physical functioning and disability risk in mobility-limited older adults: Results from the LIFE study randomized trial. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garshol, B.F.; Ellingsen-Dalskau, L.; Pedersen, I. Physical activity in people with dementia attending farm-based dementia day care–a comparative actigraphy study. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, S.F.; Rahman, A.; Beuscher, L.; Jani, V.; Durkin, D.W.; Schnelle, J.F. Resident-directed long-term care: Staff provision of choice during morning care. Gerontologist 2011, 51, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkerk, M.A. The care perspective and autonomy. Med. Health Care Philos. 2001, 4, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, B. Autonomy and the relationship between nurses and older people. Ageing Soc. 2001, 21, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, L.A.; Brazda, M.A. Transferring control to others: Process and meaning for older adults in assisted living. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2013, 32, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosisio, F.; Barazzetti, G. Advanced care planning: Promoting autonomy in caring for people with dementia. Am. J. Bioeth. 2020, 20, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, G. Recognising the agency of people with dementia. Disabil. Soc. 2014, 29, 1130–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dröes, R.M.; Chattat, R.; Diaz, A.; Gove, D.; Graff, M.; Murphy, K.; Verbeek, H.; Vernooij-Dassen, M.J.F.J.; Clare, L.; Johannessen, A.; et al. Social health and dementia: A European consensus on the operationalization of the concept and directions for research and practice. Aging Ment. Health 2017, 21, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Measuring the Age-Friendliness of Cities: A Guide to Using Core Indicators; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Marston, H.R.; van Hoof, J. “Who doesn’t think about technology when designing urban environments for older people?” A case study approach to a proposed extension of the WHO’s age-friendly cities model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilster, S.D.; Boltz, M.; Dalessandro, J.L. Long-term care workforce issues: Practice principles for quality dementia care. Gerontologist 2018, 58, S103–S113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaszak-Holl, J.; Castle, N.G.; Lin, M.K.; Shrivastwa, N.; Spreitzer, G. The role of organizational culture in retaining nursing workforce. Gerontologist 2015, 55, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, J.; Tan, P.-L.; Hoverman, S.; Baldwin, C. The value and limitations of participatory action research methodology. J. Hydrol. 2012, 474, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The Global Network for Age-Friendly Cities and Communities: Looking Back over the Last Decade, Looking forward to the Next; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Boer, B.; Bozdemir, B.; Jansen, J.; Hermans, M.; Hamers, J.P.H.; Verbeek, H. The Homestead: Developing a Conceptual Framework through Co-Creation for Innovating Long-Term Dementia Care Environments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010057

de Boer B, Bozdemir B, Jansen J, Hermans M, Hamers JPH, Verbeek H. The Homestead: Developing a Conceptual Framework through Co-Creation for Innovating Long-Term Dementia Care Environments. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(1):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010057

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Boer, Bram, Belkis Bozdemir, Jack Jansen, Monique Hermans, Jan P. H. Hamers, and Hilde Verbeek. 2021. "The Homestead: Developing a Conceptual Framework through Co-Creation for Innovating Long-Term Dementia Care Environments" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 1: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010057

APA Stylede Boer, B., Bozdemir, B., Jansen, J., Hermans, M., Hamers, J. P. H., & Verbeek, H. (2021). The Homestead: Developing a Conceptual Framework through Co-Creation for Innovating Long-Term Dementia Care Environments. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010057