Complementary Methods in Cancer Treatment—Cure or Curse?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Questionnaire

2.2. Survey Sample

2.3. Sample Size Calculation

- Z1−α/2 is a standard normal variate at 5% type 1 error (p < 0.05).

- p is an expected proportion in population based on previous studies or pilot studies.

- Finally, d is an absolute error or precision (equal to 5%).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Group Characteristics

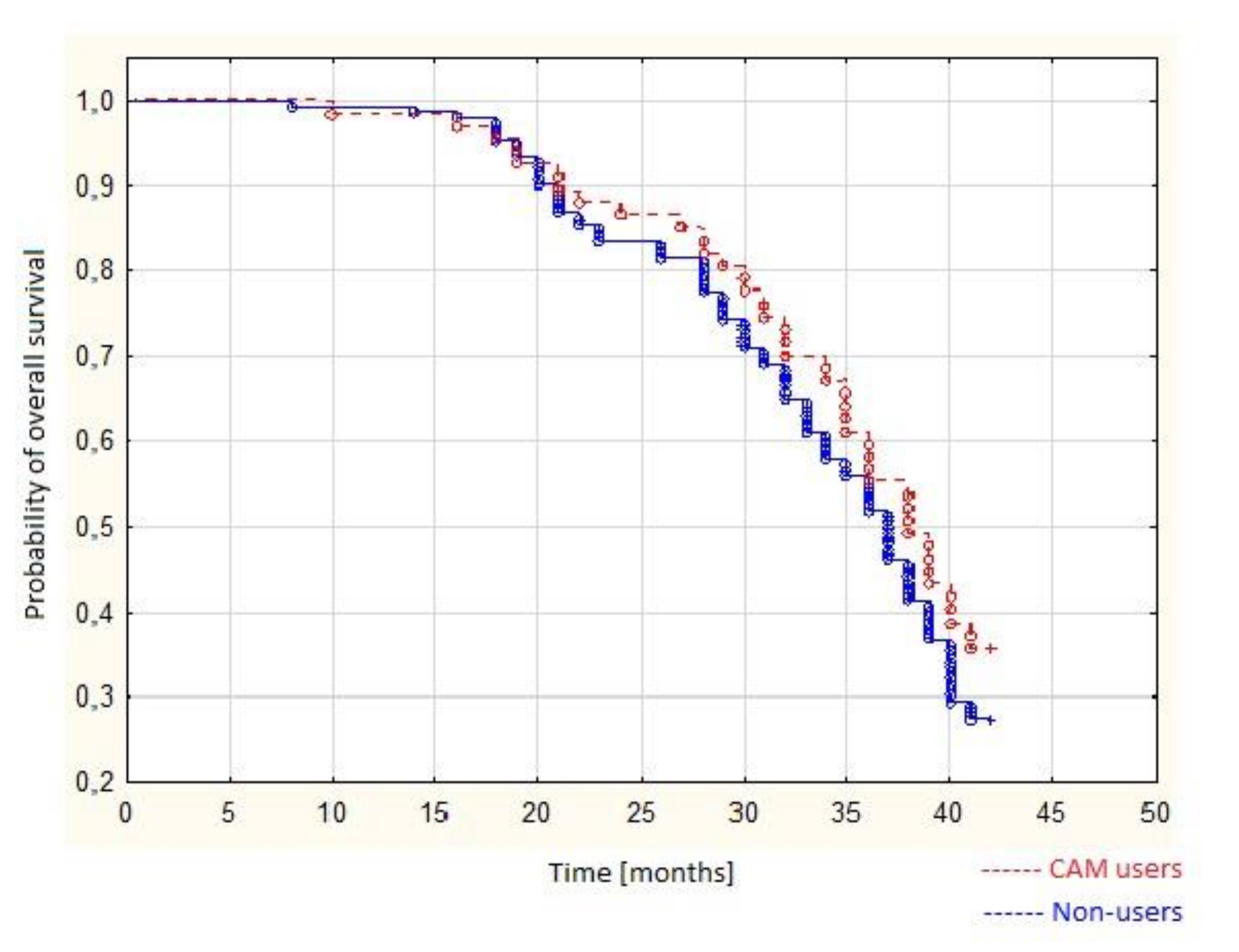

3.2. Survival Analysis Using the Kaplan–Meier Curves and COX Regression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

|

| QUESTIONNAIRE EVALUATING PATIENTS’ APPROACH TO COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE |

- How big is your city of residence?

- (a)

- City < 5.000 habitants

- (b)

- City >5.000 and <20.000 habitants

- (c)

- City >20.000 and <100.000 habitants

- (d)

- City >100.000 and <200.000 habitants

- (e)

- City > 200.000 habitants

- (f)

- Countryside

- Please choose your education level:

- (a)

- Primary

- (b)

- Junior high school

- (c)

- Vocational

- (d)

- Senior high school

- (e)

- Higher

- What is your martial status?

- (a)

- Single

- (b)

- Married

- For how many years have you had the neoplasm? (Please enter the number of years)

- Do you think that unconventional methods of therapy can be effective and able to help treat a neoplasm?

- (a)

- Yes

- (b)

- No

- (c)

- I don’t know

- Do you think that unconventional medicine can complement traditional methods of therapy?

- (a)

- Yes

- (b)

- No

- (c)

- I don’t know

- Do you think that alternative medicine can replace traditional forms of therapy?

- (a)

- Yes

- (b)

- No

- (c)

- I don’t know

- Do you think that unconventional methods of therapy are safe?

- (a)

- Yes, they are safe

- (b)

- No, they are not safe

- Do you think that a person using unconventional methods of treatment should inform their doctor about such practice?

- (a)

- Yes

- (b)

- No

- (c)

- I don’t know

- Have you ever used complementary methods of treatment?

- (a)

- Yes

- (b)

- No

- 11.

- How often do you use complementary methods of treatment?

- (a)

- Very rarely

- (b)

- Occasionally

- (c)

- Quite often

- (d)

- Very often

- 12.

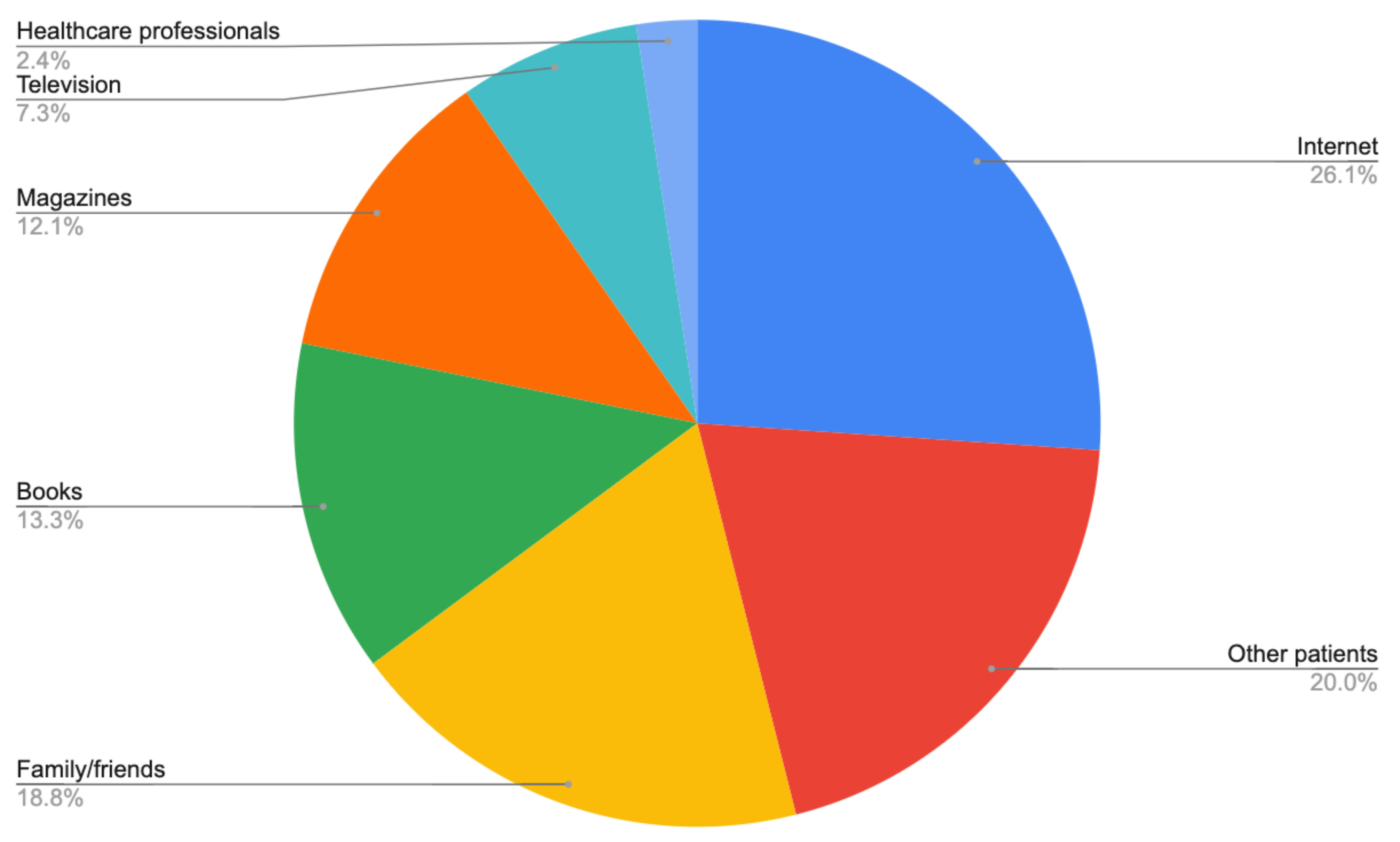

- Where did you learn about complementary and alternative methods of treatment? (you can select more than one answer)

- (a)

- Internet

- (b)

- TV

- (c)

- Books

- (d)

- Magazines

- (e)

- Family/friends

- (f)

- Other cancer patients

- (g)

- Medical professionals

- 13.

- What are/were your reasons for use of unconventional medicine? (you can choose more than one answer and/or write your own answer)

- (a)

- No effect of traditional/standard treatment

- (b)

- To relieve the side effects of standard treatment (chemotherapy/ radiotherapy)

- (c)

- Positive feedback from other patients

- (d)

- Influence of friends/family

- 14.

- Have you noticed any improvement in your health that you associate with the use of complementary forms of therapy?

- (a)

- Yes

- (b)

- No

- (c)

- Difficult to say

- 15.

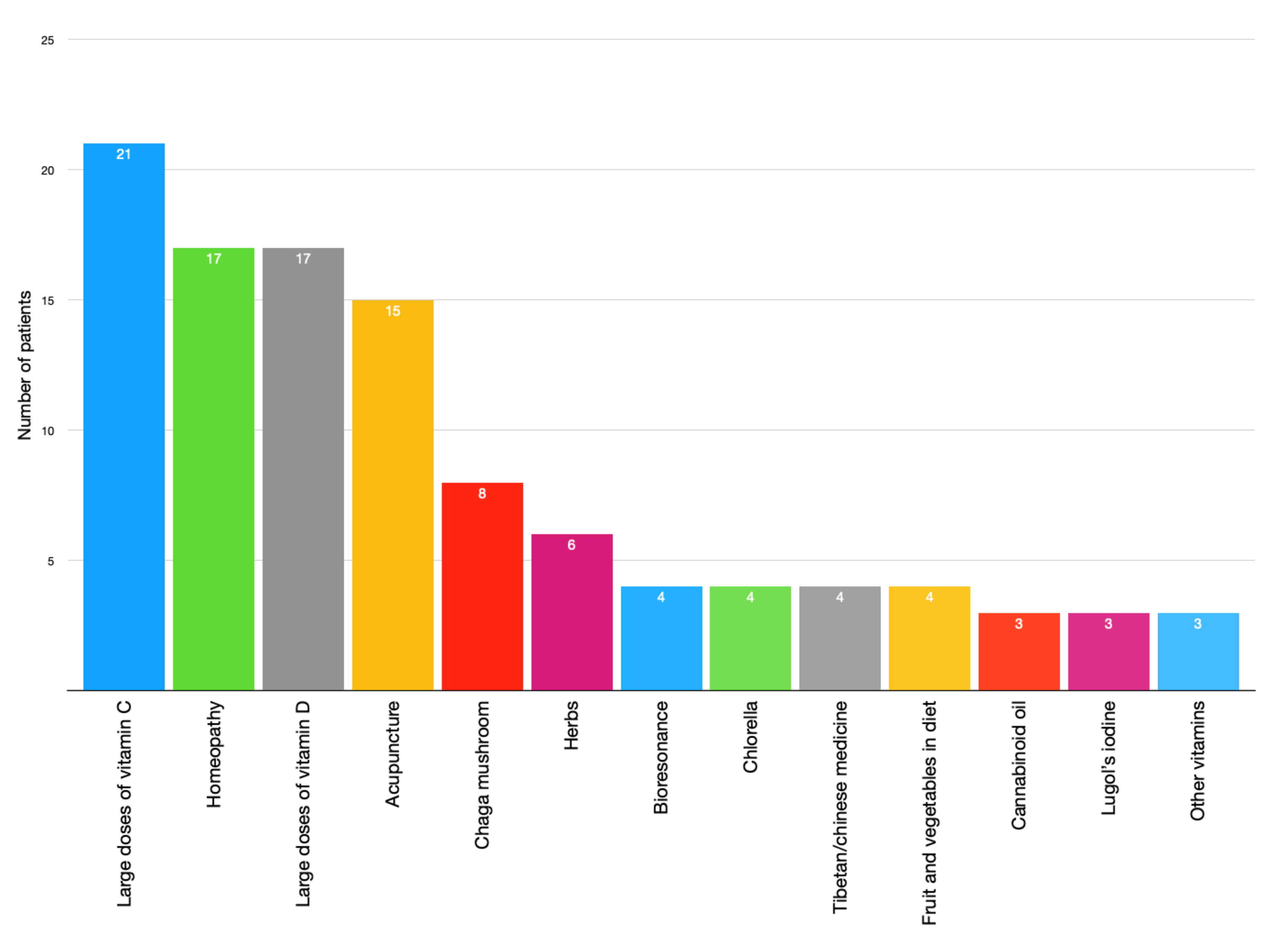

- What kind of therapy do/did you use? (you can select more than one answer and/or write your own answer)

- (a)

- Homeopathy

- (b)

- Chinese/Tibetan medicine

- (c)

- Bioresonance

- (d)

- Acupressure/ reflexotherapy

- (e)

- Acupuncture

- (f)

- Ozone therapy

- (g)

- Large doses of Vitamin C

- (h)

- Large doses of Vitamin D

- (i)

- Lugol’s iodine

- (j)

- Silver water

- (k)

- Chlorella

- (l)

- Chaga mushrooms

- (m)

- Other: ……………

References

- Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What’s in a Name? | NCCIH. Available online: https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/complementary-alternative-or-integrative-health-whats-in-a-name (accessed on 24 October 2020).

- Clarke, T.C.; Black, L.I.; Stussman, B.J.; Barnes, P.M.; Nahin, R.L. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002–2012. Natl. Health Stat. Rep. 2015, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, M.A.; Sanders, T.; Palmer, J.L.; Greisinger, A.; Singletary, S.E. Complementary/alternative medicine use in a comprehensive cancer center and the implications for oncology. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000, 18, 2505–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernst, E. Intangible risks of complementary and alternative medicine. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001, 19, 2365–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risberg, T.; Vickers, A.; Bremnes, R.M.; Wist, E.A.; Kaasa, S.; Cassileth, B.R. Does use of alternative medicine predict survival from cancer? Eur. J. Cancer 2003, 39, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparreboom, A.; Cox, M.C.; Acharya, M.R.; Figg, W.D. Herbal remedies in the United States: Potential adverse interactions with anticancer agents. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 2489–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gansler, T.; Kaw, C.; Crammer, C.; Smith, T. A population-based study of prevalence of complementary methods use by cancer survivors: A report from the American cancer society’s studies of cancer survivors. Cancer 2008, 113, 1048–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vapiwala, N.; Mick, R.; Hampshire, M.K.; Metz, J.M.; DeNittis, A.S. Patient initiation of complementary and alternative medical therapies (CAM) following cancer diagnosis. Cancer J. 2006, 12, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navo, M.A.; Phan, J.; Vaughan, C.; Palmer, J.L.; Michaud, L.; Jones, K.L.; Bodurka, D.C.; Basen-Engquist, K.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; Kavanagh, J.J.; et al. An assessment of the utilization of complementary and alternative medication in women with gynecologic or breast malignancies. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dy, G.K.; Bekele, L.; Hanson, L.J.; Furth, A.; Mandrekar, S.; Sloan, J.A.; Adjei, A.A. Complementary and alternative medicine use by patients enrolled onto phase I clinical trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 4758–4763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponholzer, A.; Struhal, G.; Madersbacher, S. Frequent use of complementary medicine by prostate cancer patients. Eur. Urol. 2003, 43, 604–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.; McNulty, A.; Caress, A.L. Current issues in the delivery of complementary therapies in cancer care—Policy, perceptions and expectations: An overview. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2005, 9, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boon, H.; Stewart, M.; Kennard, M.A.; Gray, R.; Sawka, C.; Brown, J.B.; McWilliam, C.; Gavin, A.; Baron, R.A.; Aaron, D.; et al. Use of complementary/alternative medicine by breast cancer survivors in Ontario: Prevalence and perceptions. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000, 18, 2515–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, C.G.; Christensen, S.; Jensen, A.B.; Zachariae, R. Prevalence, socio-demographic and clinical predictors of post-diagnostic utilisation of different types of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in a nationwide cohort of Danish women treated for primary breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 3172–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humpel, N.; Jones, S.C. Gaining insight into the what, why and where of complementary and alternative medicine use by cancer patients and survivors. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl.) 2006, 15, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risberg, T.; Kaasa, S.; Wist, E.; Melsom, H. Why are cancer patients using non-proven complementary therapies? A cross-sectional multicentre study in Norway. Eur. J. Cancer Part A 1997, 33, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparber, A.; Bauer, L.; Curt, G.; Eisenberg, D.; Levin, T.; Parks, S.; Steinberg, S.M.; Wootton, J. Use of complementary medicine by adult patients participating in cancer clinical trials. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2000, 27, 623–630. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, E. The role of complementary and alternative medicine in cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2000, 1, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, J. An analysis of paper-based sources of information on complementary therapies. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2007, 13, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gorkom, G.N.Y.; Lookermans, E.L.; van Elssen, C.H.M.J.; Bos, G.M.J. The effect of vitamin C (Ascorbic acid) in the treatment of patients with cancer: A systematic review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, C.; Hutton, B.; Ng, T.; Shorr, R.; Clemons, M. Is There a Role for Oral or Intravenous Ascorbate (Vitamin C) in Treating Patients with Cancer? A Systematic Review. Oncologist 2015, 20, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, B.R.; Alexander, M.S.; Du, J.; Moose, D.L.; Henry, M.D.; Cullen, J.J. Pharmacological ascorbate inhibits pancreatic cancer metastases via a peroxide-mediated mechanism. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauman, G.; Gray, J.C.; Parkinson, R.; Levine, M.; Paller, C.J. Systematic review of intravenous ascorbate in cancer clinical trials. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeller, T.; Muenstedt, K.; Stoll, C.; Schweder, J.; Senf, B.; Ruckhaeberle, E.; Becker, S.; Serve, H.; Huebner, J. Potential interactions of complementary and alternative medicine with cancer therapy in outpatients with gynecological cancer in a comprehensive cancer center. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 139, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiani, J.; Imam, S.Z. Medicinal importance of grapefruit juice and its interaction with various drugs. Nutr. J. 2007, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, F.; Izzo, A.A. Herb-drug interactions with St John’s Wort (hypericum perforatum): An update on clinical observations. AAPS J. 2009, 11, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasinu, P.S.; Rapp, G.K. Herbal Interaction with Chemotherapeutic Drugs—A Focus on Clinically Significant Findings. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molassiotis, A.; Fernandez-Ortega, P.; Pud, D.; Ozden, G.; Scott, J.A.; Panteli, V.; Margulies, A.; Browall, M.; Magri, M.; Selvekerova, S.; et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients: A European survey. Ann. Oncol. 2005, 16, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molassiotis, A.; Xu, M. Quality and safety issues of web-based information about herbal medicines in the treatment of cancer. Complement. Ther. Med. 2004, 12, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.B.; Park, H.S.; Gross, C.P.; Yu, J.B. Complementary Medicine, Refusal of Conventional Cancer Therapy, and Survival among Patients with Curable Cancers. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 1375–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.B.; Park, H.S.; Gross, C.P.; Yu, J.B. Use of alternative medicine for cancer and its impact on survival. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, D.K.; Lewith, G.; Stephenss, C.R.; Bryden, H. Can doctors respond to patients’ increasing interest in complementary and alternative medicine? BMJ 2001, 322, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total Number of Patients n = 316 (%) | Complementary and Alternative Method (CAM) Users n = 87 (%) | Non-Users n = 229 (%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place of Residence | 0.570 | |||

| City <5000 habitants | 25 (7.9) | 8 (9.2) | 17 (7.4) | |

| City >5000 and <20,000 habitants | 49 (15.5) | 12 (13.8) | 37 (16.2) | |

| City >20,000 and <100,000 habitants | 67 (21.2) | 21 (24.1) | 46 (20.1) | |

| City >100,000 and <200,000 habitants | 16 (5.1) | 2 (2.3) | 14 (6.1) | |

| City >200,000 habitants | 104 (32.9) | 26 (29.9) | 78 (34.1) | |

| Countryside | 55 (17.4) | 18 (20.7) | 37 (16.2) | |

| Education | 0.671 | |||

| Primary | 27 (8.5) | 7 (8.1) | 20 (8.7) | |

| Junior High School | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.9) | |

| Vocational | 65 (20.6) | 16 (18.4) | 49 (21.4) | |

| Senior High School | 140 (44.3) | 37 (42.5) | 103 (45.0) | |

| Higher | 82 (26.0) | 27 (31.0) | 55 (24.0) | |

| Oncological Status | 0.943 | |||

| Newly diagnosed (less than 2 years) | 154 (48.7) | 41 (47.1) | 113 (49.3) | |

| Treated for more than 2 and less than 6 years | 86 (27.2) | 23 (26.5) | 63 (27.5) | |

| Treated for more than 6 years | 69 (21.9) | 21 (24.1) | 48 (21.0) | |

| Did not answer | 7 (2.2) | 2 (2.3) | 5 (2.2) | |

| CAM USE | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Marital status (Married vs. single) | 0.69 | 0.39–1.22 | 0.203 |

| Place of residence (city vs. countryside) | 0.66 | 0.36–1.21 | 0.178 |

| Education (higher vs. other) | 1.323 | 0.70–2.51 | 0.392 |

| Age (above vs. below median) | 0.88 | 0.50–1.57 | 0.675 |

| FIGO staging (III and IV vs. I and II) | 1.13 | 0.61–2.07 | 0.700 |

| Chemotherapy protocol (standard vs. other) | 2.33 | 1.26–4.34 | 0.007 |

| Recurrence (yes vs. no) | 0.74 | 0.35–1.57 | 0.433 |

| CAM Use | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Marital status (Married vs. single) | 0.59 | 0.33–1.18 | 0.226 |

| Place of residence (city vs. countryside) | 0.84 | 0.60–1.92 | 0.371 |

| Education (higher vs. other) | 1.41 | 0.75–1.72 | 0.032 |

| Age (above vs. below median) | 0.93 | 0.49–2.06 | 0.711 |

| FIGO staging (III and IV vs. I and II) | 1.22 | 0.76–1.89 | 0.058 |

| Chemotherapy protocol (standard vs. other) | 1.96 | 1.18–2.43 | 0.012 |

| Recurrence (yes vs. no) | 0.88 | 0.41–1.38 | 0.052 |

| Declared CAM Use | Thinks that Unconventional Methods of Therapy are Safe (in Number of Patients) | |

|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |

| No | 166 | 29 |

| Yes | 35 | 36 |

| Patients’ Education | Thinks that Alternative Medicine can Replace Traditional Therapy (in Number of Patients) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Doesn’t Know | |

| Higher | 6 | 52 | 24 |

| Senior High School | 13 | 69 | 57 |

| Vocational | 12 | 23 | 30 |

| Primary | 4 | 7 | 16 |

| Junior High School | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Multivariate Analysis (Cox Regression Model) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| CAM use (users vs. non users) | 0.98 | 0.71–1.16 | 0.066 |

| Age (above vs. below median) | 1.12 | 0.84–1.39 | 0.023 |

| Marital status (Married vs. single) | 0.79 | 0.63–0.99 | 0.073 |

| FIGO staging (III and IV vs. I and II) | 1.41 | 1.11–1.71 | 0.01 |

| Recurrence (yes vs. no) | 1.26 | 1.02–1.39 | 0.044 |

| Chemotherapy protocol (standard vs. other) | 0.91 | 0.69–1.12 | 0.071 |

| Education (higher vs. other) | 0.78 | 0.63–0.98 | 0.103 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Michalczyk, K.; Pawlik, J.; Czekawy, I.; Kozłowski, M.; Cymbaluk-Płoska, A. Complementary Methods in Cancer Treatment—Cure or Curse? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010356

Michalczyk K, Pawlik J, Czekawy I, Kozłowski M, Cymbaluk-Płoska A. Complementary Methods in Cancer Treatment—Cure or Curse? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(1):356. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010356

Chicago/Turabian StyleMichalczyk, Kaja, Jakub Pawlik, Izabela Czekawy, Mateusz Kozłowski, and Aneta Cymbaluk-Płoska. 2021. "Complementary Methods in Cancer Treatment—Cure or Curse?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 1: 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010356

APA StyleMichalczyk, K., Pawlik, J., Czekawy, I., Kozłowski, M., & Cymbaluk-Płoska, A. (2021). Complementary Methods in Cancer Treatment—Cure or Curse? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(1), 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010356