How CSV and CSR Affect Organizational Performance: A Productive Behavior Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. CSV and CSR

2.2. Work Engagement

2.3. Productive Behavior

2.3.1. OCB

2.3.2. Innovative Behavior

2.3.3. Job Performance

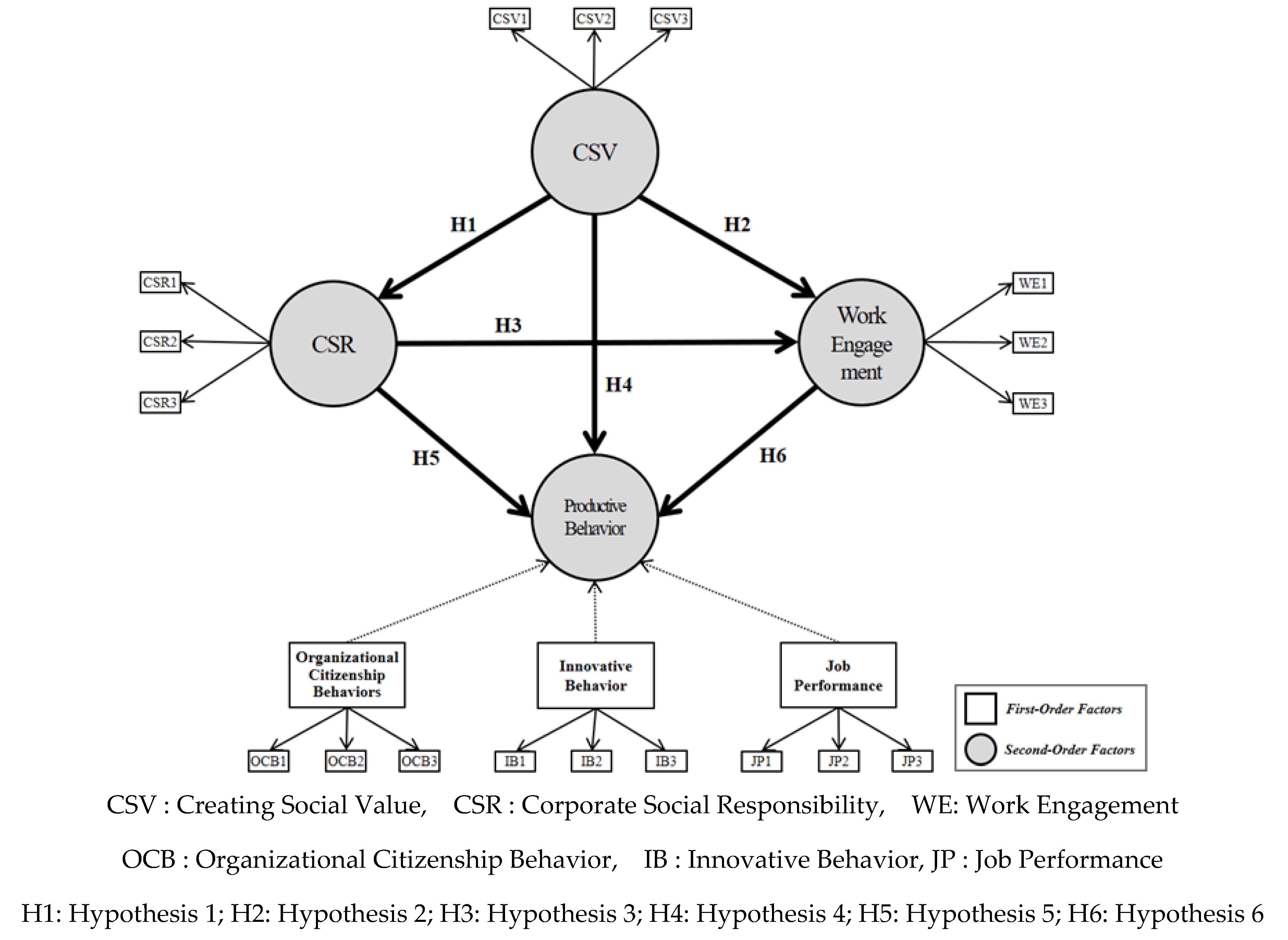

2.4. Research Model and Hypothesis

2.5. Hypothesis and Sample Collection

3. Results

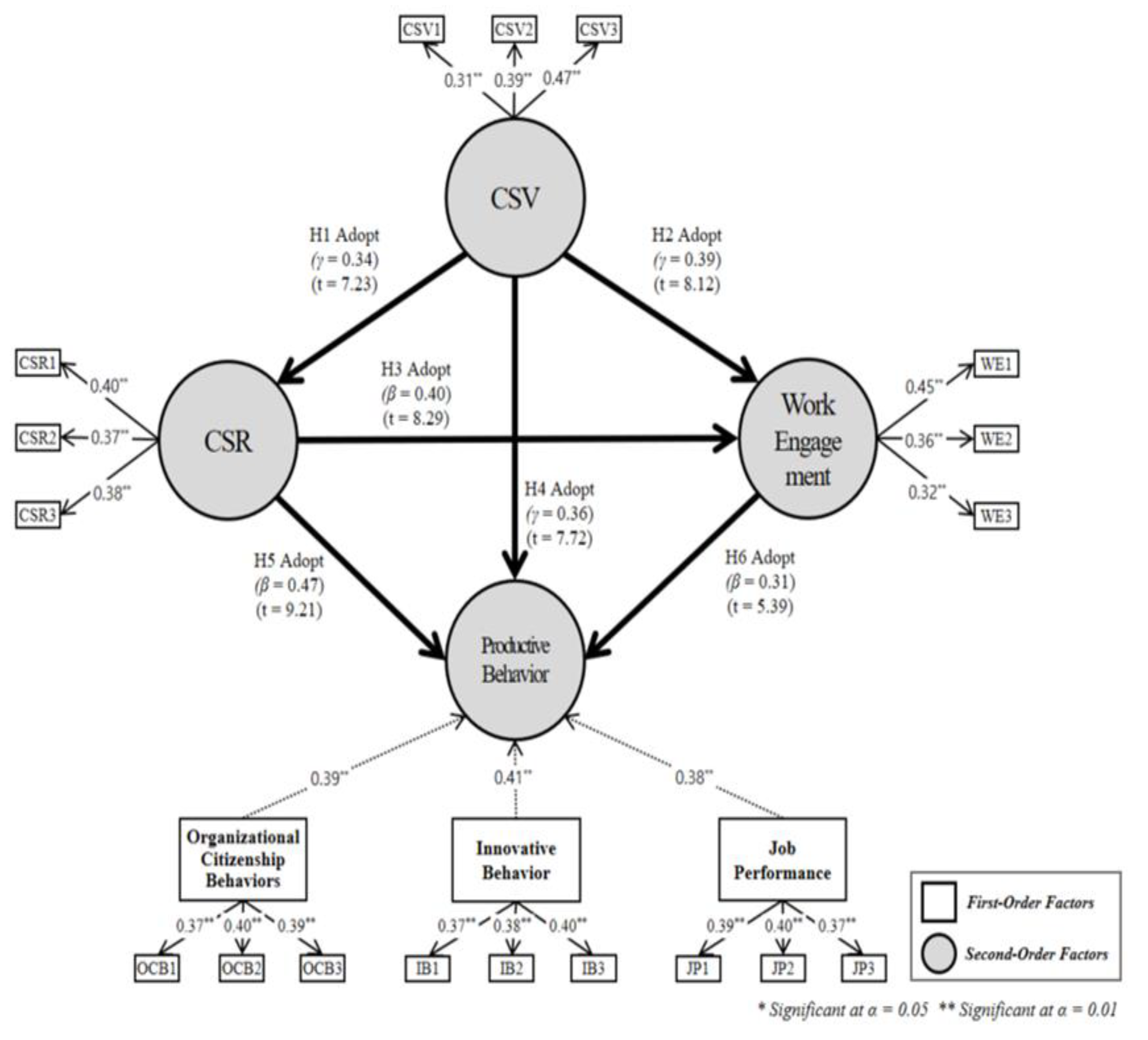

The Model Structure

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does doing good always lead to doing better? consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.C. Corporate social responsibility and marketing: An integrative framework. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2004, 32, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, T.; Iqbal, S.; Ma, J.; Castro-González, S.; Khattak, A.; Khan, M.K. Employees’ perceptions of CSR, work engagement, and organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating effects of organizational justice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.J.; Nurunnabi, M.; Kim, T.H.; Jung, S.Y. Does a good firm breed good organizational citizens? The moderating role of perspective taking. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, M.A.; Qaied, B.A.A.; Al-Mawali, H.; Matalqa, M. What drives employee’s involvement and turnover intentions: Empirical investigation of factors influencing employee involvement and turnover intentions? IRMM 2016, 6, 298–306. [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron, D.; Ostroff, C.; Schroeder, T.; Block, C. The dual effects of organizational citizenship behavior: Relationships to research productivity and career outcomes in academe. Hum. Perform. 2014, 27, 99–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.S.; Gurhan-Canli, Z.; Schwarz, N. The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) on companies with bad reputation. J. Consum. Psychol. 2006, 16, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steve, M.J.; Thomas, W.B. Organizational Psychology: A Scientist-Practitioner Approach, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Robert, H. Software Piracy on the Internet: A Threat to Your Security; Business Software Alliance: Washington, WA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, H.R. Social Responsibilities of the Businessman; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Strategy and Society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N.C. Corporate social responsibility: Whether or how? Calif. Manag. Rev. 2003, 45, 52–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadal, H.; Sharma, R.D. Implications of corporate social responsibility on marketing performance: A conceptual framework. J. Serv. Res. 2006, 6, 205–216. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Korschun, D. The role of corporate social responsibility in strengthening multiple stakeholder relationships: A field experiment. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, D.R.; Drumwright, M.E.; Braig, B.M. The effect of corporate social responsibility on customer donations to corporate-supported nonprofits. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Consumer-company identification: A framework for understanding consumer’s relationships with companies. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; Gonzalez-Roma, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of burnout and engagement: A confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demand, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Jensen, S.M. Hope: A new positive strength for human resource development. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2002, 1, 304–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.C.; Park, J.W. Examining structural relationships between work engagement, organizational procedural justice, knowledge sharing, and innovative work behavior for sustainable organizations. Sustainability 2017, 9, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.A.; Organ, D.W.; Near, J.P. Organizational citizenship behavior: Its nature and antecedents. J. Appl. Psychol. 1983, 68, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D. The motivational basis of organizational behavior. Behav. Sci. 1964, 9, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.O. The Relationship between Power Type, Work Engagement, and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating shared value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.R.; Lee, M.; Lee, H.T.; Kim, N.M. Corporate social responsibility and employee–company identification. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; Whiting, S.W.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Blume, B.D. Individual-and organizational-level consequences of organizational citizenship behaviors: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posdakoff, P.M.; Mackenzie, S.B. Organizational citizenship behaviors and sales unit effectiveness. J. Mark. Res. 1994, 31, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheng, Y.K.; Mahmood, R. The relationship between pro-innovation organization climate, leader-member exchange and innovative work behavior: A study among the knowledge workers of the knowledge intensive business service in Malaysia. Bus. Manag. Dyn. 2013, 2, 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Farr, J.L.; West, M.A. Innovation and Creativity at Work: Psychological and Organizational Strategies; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, U.A.; Datta, S.; Blake-Beard, S.; Bhargava, S. Linking LMX, Innovative work behaviour and turnover intentions: The mediating role of work engagement. Career Dev. Int. 2012, 17, 208–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O. Job demands, perceptions of effort-reward fairness and innovative work behavior. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2000, 73, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.G.; Bruce, R.A. Determinants of innovative behavior: A path model of individual innovation in the workplace. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 580–607. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, J.M. Distinguishing contextual performance from task performance for managerial jobs. J. Appl. Psychol. 1999, 84, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.R. Toward a Broader Conception of Jobs and Job Performance: Impact of Changes in the Military Environment on the Structure, Assessment, and Prediction of Job Performance; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barrick, M.R.; Mount, M.K. Yes, personality matters: Moving on to more important matters. Hum. Perform. 2005, 18, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.C.; Kolb, J.A.; Kim, T.S. The relationship between work engagement and performance: A review of empirical literature and a proposed research Agenda. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2012, 12, 248–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, D.; Ting, L.; Palmer, A. A Journey into the unknown; Taking the fear out of structural equation modeling with AMOS for the first-time user. Mark. Rev. 2008, 8, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Items | References |

|---|---|---|

| Creating Social Value | “Win-Win” awareness by business and society | Porter and Kramer (2011) [26] Kim et al. (2010) [27] |

| Using resources and capabilities for “Win-Win” | ||

| Contributing to social development and contribution activities | ||

| Corporate Social Responsibility | Accepting the needs of society | Porter and Kramer(2011) [26] Yoon et al. (2006) [7] Sen and Bhattacharya (2001) [1] |

| Exerting efforts to solve social problems | ||

| Improving social welfare or quality of life | ||

| Work Engagement | Attributing value to work | Schaufeli et al. (2006) [19] Bhattacharya and Sen (2003) [16] Schaufeli et al. (2002) [17] |

| Passionate about work | ||

| Work immersion | ||

| OrganizationalCitizenship Behavior | Helping colleagues with problems encountered while working | Park (2019) [24] Podsakoff et al. (2009) [28] |

| Making efforts to achieve results beyond standards | ||

| Loyalty and pride about the company | ||

| Innovative Behavior | Proposing creative working methods | Agarwal et al. (2012) [32] Kheng and Mahmood (2013) [30] |

| Generating ideas for solving work-related problems | ||

| Focusing on creativity, innovation, and challenges while working | ||

| Job Performance | Performing given tasks perfectly | Kim and Park (2017) [21] Barrick and Mount (2005) [37] |

| Completing tasks with a sense of responsibility | ||

| Meeting company expectations |

| Frequency | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age of Respondent | ||

| 30–40 | 95 | 49 |

| 40–50 | 68 | 35 |

| Over 50 | 32 | 16 |

| Gender of Respondent | ||

| Male | 118 | 61 |

| Female | 77 | 39 |

| Job Tenure of Respondent | ||

| 1–5 | 75 | 38 |

| 5–10 | 63 | 32 |

| Over 10 | 57 | 30 |

| Title of Respondent | ||

| Assistant manager | 67 | 34 |

| Manager | 62 | 32 |

| General manager | 46 | 24 |

| Executive director | 20 | 10 |

| Item | Job Performance | Work Engagement | CSR | Innovative Behavior | OCB | CSV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSV1 | −0.091 | 0.308 | −0.002 | 0.019 | 0.132 | 0.751 |

| CSV2 | 0.075 | 0.028 | 0.251 | 0.249 | 0.058 | 0.823 |

| CSV3 | 0.131 | 0.26 | 0.066 | 0.163 | 0.266 | 0.788 |

| CSR1 | 0.283 | 0.195 | 0.814 | 0.182 | 0.161 | 0.011 |

| CSR2 | 0.145 | 0.279 | 0.845 | 0.127 | 0.138 | 0.133 |

| CSR3 | 0.199 | 0.232 | 0.737 | 0.279 | 0.209 | 0.221 |

| WE1 | 0.105 | 0.822 | 0.201 | 0.226 | 0.177 | 0.201 |

| WE2 | −0.002 | 0.836 | 0.28 | 0.215 | 0.056 | 0.14 |

| WE3 | 0.148 | 0.825 | 0.175 | 0.047 | 0.091 | 0.24 |

| OCB1 | 0.28 | −0.057 | 0.048 | 0.191 | 0.777 | 0.173 |

| OCB2 | 0.195 | 0.187 | 0.211 | 0.196 | 0.773 | 0.147 |

| OCB3 | 0.091 | 0.204 | 0.209 | 0.144 | 0.872 | 0.129 |

| IB1 | 0.132 | 0.236 | 0.369 | 0.779 | 0.202 | 0.141 |

| IB2 | 0.195 | 0.145 | 0.238 | 0.874 | 0.183 | 0.138 |

| IB3 | 0.327 | 0.176 | 0.033 | 0.781 | 0.238 | 0.228 |

| JP1 | 0.855 | 0.069 | 0.108 | 0.263 | 0.191 | 0.049 |

| JP2 | 0.872 | 0.016 | 0.195 | 0.265 | 0.094 | 0.007 |

| JP3 | 0.807 | 0.173 | 0.271 | 0.003 | 0.277 | 0.039 |

| CSV: Creating Social Value, CSR: Corporate Social Responsibility, Work Engagement OCB: Organizational Citizenship Behavior, Innovative Behavior, Job Performance | ||||||

| Constructs | AVE | CR | Cronbach α |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSV | 0.72 | 0.832 | 0.804 |

| CSR | 0.829 | 0.927 | 0.893 |

| Work Engagement | 0.786 | 0.846 | 0.829 |

| OCB | 0.792 | 0.872 | 0.861 |

| Innovative Behavior | 0.841 | 0.931 | 0.923 |

| Job Performance | 0.834 | 0.929 | 0.897 |

| Construct | CSV | CSR | Work Engagement | OCB | Innovative Behavior | Job Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSV | 0.849 | |||||

| CSR | 0.378 ** | 0.910 | ||||

| Work Engagement | 0.494 ** | 0.457 ** | 0.887 | |||

| OCB | 0.417 ** | 0.369 ** | 0.361 ** | 0.890 | ||

| Innovative Behavior | 0.344 ** | 0.412 ** | 0.469 ** | 0.418 ** | 0.917 | |

| Job Performance | 0.298 ** | 0.398 ** | 0.283 ** | 0.376 ** | 0.403 ** | 0.913 |

| Tolerance | VIF | Tolerance | VIF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSV | 0.740 | 1.352 | CSR | 0.676 | 1.479 |

| Work Engagement | 0.596 | 1.679 | Dependent Variable: Productive Behavior | ||

| Recommended Value | Measurement Model | |

|---|---|---|

| Fit statistic | X2/DF (≤3.000) | 2.720 |

| RMSR (≤0.050) | 0.039 | |

| RMSEA (≤0.080) | 0.052 | |

| AGFI (≥0.800) | 0.824 | |

| CFI (≥0.900) | 0.918 | |

| TLI (≥0.900) | 0.891 | |

| PGFI (≥0.600) | 0.627 | |

| CSR | Work Engagement | Productive Behavior | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSV | Direct Effect | 0.34 | 0.39 ** | 0.36 ** |

| Indirect Effect | - | 0.12 ** | 0.13 ** | |

| Total Effect | 0.34 | 0.51 ** | 0.49 ** | |

| CSR | Direct Effect | 0.40 ** | 0.47 ** | |

| Indirect Effect | - | 0.05 | ||

| Total Effect | 0.40 ** | 0.52 ** | ||

| Work Engagement | Direct Effect | 0.31 * | ||

| Indirect Effect | - | |||

| Total Effect | 0.31 * |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, K.O. How CSV and CSR Affect Organizational Performance: A Productive Behavior Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2556. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072556

Park KO. How CSV and CSR Affect Organizational Performance: A Productive Behavior Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(7):2556. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072556

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Kwang O. 2020. "How CSV and CSR Affect Organizational Performance: A Productive Behavior Perspective" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 7: 2556. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072556

APA StylePark, K. O. (2020). How CSV and CSR Affect Organizational Performance: A Productive Behavior Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2556. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072556