Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health and Quality of Life among Local Residents in Liaoning Province, China: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

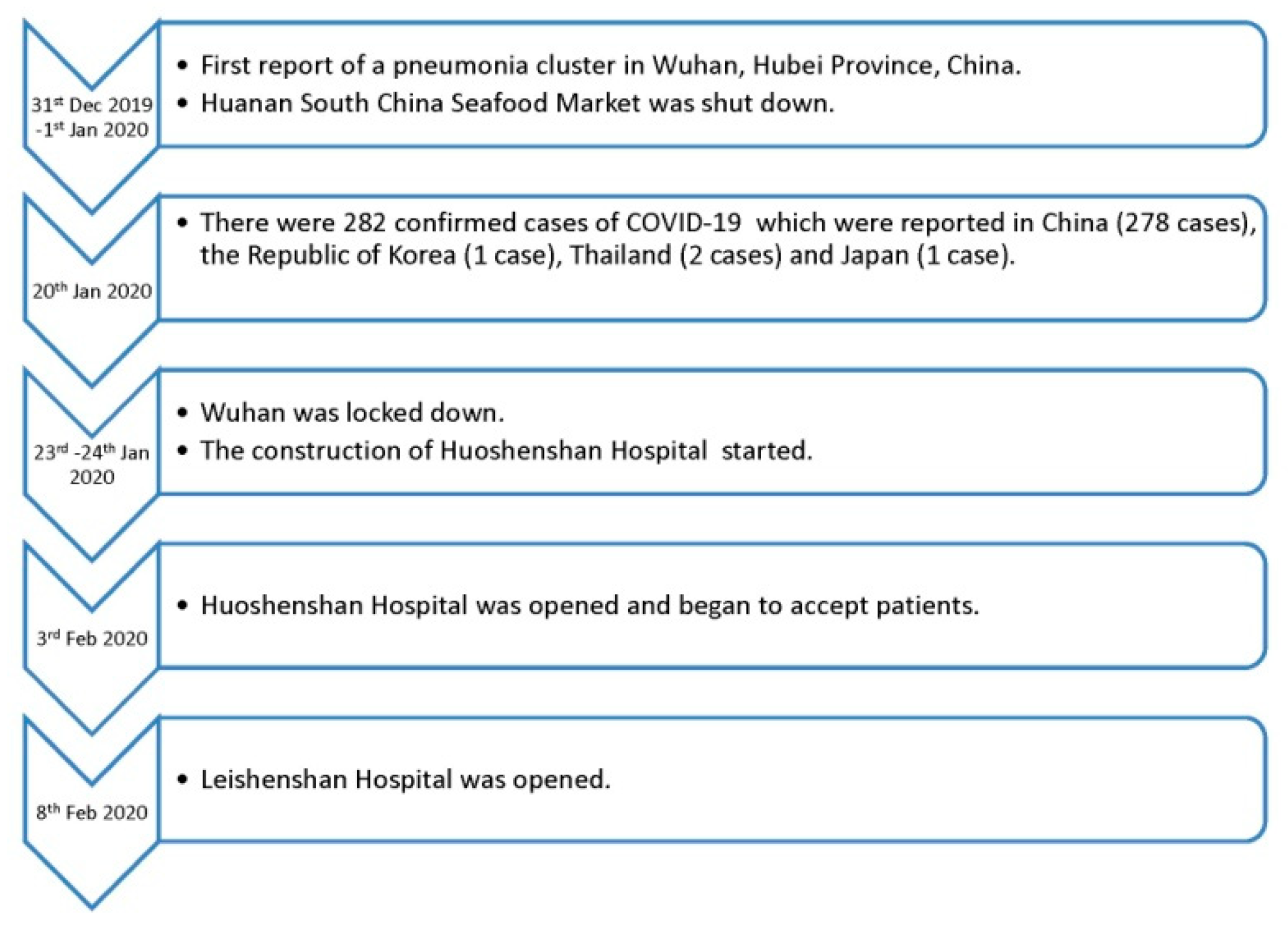

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Impact of Event Scale (IES)

2.2. Other Indicators of Negative Mental Health Impact

2.3. Impact on Social and Family Support

2.4. Impact on Mental Health-Related Lifestyle Changes

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. IES

3.3. Other Indicators of Negative Mental Health Impact

3.4. Impact on Social and Family Support

3.5. Impact on Mental Health-Related Lifestyle Changes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wuhan Municipal Health Commission. Wuhan Municipal Health Commission’s Briefing on the Pneumonia Epidemic Situation. Available online: http://wjw.wuhan.gov.cn/front/web/showDetail/2019123108989 (accessed on 31 December 2019).

- Wilder-Smith, A.; Chiew, C.J.; Lee, V.J. Can we contain the covid-19 outbreak with the same measures as for SARS? Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Novel Coronavirus (2019-ncov) Situation Report—22 Situations; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, D.S.; I Azhar, E.; Madani, T.A.; Ntoumi, F.; Kock, R.; Dar, O.; Ippolito, G.; Mchugh, T.D.; Memish, Z.A.; Drosten, C. The continuing 2019-ncov epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health—the latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 91, 264–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nature. Stop the Wuhan virus. Nature 2020, 577, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Tang, J.; Wei, F. Updated understanding of the outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-ncov) in Wuhan, china. J. Med. Virol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, R.L.; Donaldson, E.F.; Baric, R.S. A decade after sars: Strategies for controlling emerging coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 836–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.T.; Yang, X.; Pang, E.; Tsui, H.Y.; Wong, E.; Wing, Y.K. Sars-related perceptions in hong kong. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005, 11, 417–424. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, J.F.; Yuan, S.; Kok, K.H.; To, K.K.; Chu, H.; Yang, J.; Xing, F.; Liu, J.; Yip, C.C.; Poon, R.W.; et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: A study of a family cluster. Lancet 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, china. Lancet 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.T.; Yang, X.; Tsui, H.Y.; Pang, E.; Wing, Y.K. Positive mental health-related impacts of the sars epidemic on the general public in hong kong and their associations with other negative impacts. J. Infect. 2006, 53, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Shen, B.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Z.; Xie, B.; Xu, Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. Gen. Psychiatry 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkengasong, J. China’s response to a novel coronavirus stands in stark contrast to the 2002 sars outbreak response. Nat. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.T.; Yang, X.; Tsui, H.; Kim, J.H. Monitoring community responses to the sars epidemic in hong kong: From day 10 to day 62. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2003, 57, 864–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, J.T.; Yang, X.; Tsui, H.Y.; Kim, J.H. Impacts of sars on health-seeking behaviors in general population in hong kong. Prev. Med. 2005, 41, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | All (n = 263) | Females (n = 157) | Males (n = 106) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 37.7 ± 14.0 | 35.9 ± 14.5 | 40.3 ± 12.8 | 0.010 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.9 ± 4.3 | 21.8 ± 2.9 | 24.5 ± 5.3 | <0.001 |

| Education level, n (%) | ||||

| Secondary school | 66 (25.1) | 39 (24.8) | 27 (25.5) | 0.908 |

| Higher qualification | 197 (74.9) | 118 (75.2) | 79 (74.5) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||

| Single/Divorced | 103 (39.2) | 73 (46.5) | 30 (28.3) | 0.003 |

| Married | 160 (60.8) | 84 (53.5) | 76 (71.7) | |

| Employment status, n (%) | ||||

| Full-time | 138 (52.5) | 75 (47.8) | 63 (59.4) | 0.018 |

| Part-time | 42 (16.0) | 22 (14.0) | 20 (18.9) | |

| Students | 83 (31.6) | 60 (38.2) | 23 (21.7) | |

| Religion, n (%) | ||||

| No religion | 250 (95.1) | 148 (94.3) | 102 (96.2) | 0.328 |

| Buddhist | 11 (4.2) | 7 (4.5) | 4 (3.8) | |

| Christian | 2 (0.8) | 2(1.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Variables | B | Std. Error | Beta | t | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 8.12 | 0.3693 | – | 2.199 | 0.029 |

| Age | 0.026 | 0.037 | 0.048 | 0.706 | 0.481 |

| Sex | −1.794 | 1.019 | −0.115 | −1.76 | 0.080 |

| BMI | 0.139 | 0.118 | 0.077 | 1.175 | 0.241 |

| Education | 1.185 | 1.171 | 0.067 | 1.013 | 0.312 |

| Sex (n = 263) | P-Value 1 | Age Group (Years) (n = 263) | P-Value 1 | Education Level (n = 263) | P-Value 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Females (n = 157) | Males (n = 106) | 18–30 (n = 109) | 31–40 (n = 46) | 41–50 (n = 54) | >50 (n = 54) | Secondary School (n = 66) | Higher Qualification (n =197) | |||

| IES | 14.2 ± 7.8 | 12.8 ± 7.4 | 0.173 2 | 13.9 ± 8.1 | 13.1 ± 6.2 | 12.6 ± 7.0 | 14.5 ± 8.5 | 0.583 3 | 13.0 ± 7.6 | 13.8 ± 7.7 | 0.439 2 |

| IES ≥26, n (%) | 10 (6.4) | 10 (9.4) | 0.478 | 9 (8.3) | 1 (2.2) | 4 (7.4) | 6 (11.1) | 0.560 | 5 (7.6) | 15 (7.6) | 1.000 |

| Increased stress from work, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Yes | 50 (31.8) | 31 (29.2) | 0.685 | 34 (31.2) | 16 (34.8) | 10 (18.5) | 21 (38.9) | 0.120 | 15 (22.7) | 66 (33.5) | 0.124 |

| No | 107 (68.2) | 75 (70.8) | 75 (68.8) | 30 (65.2) | 44 (81.5) | 33 (61.1) | 51 (77.3) | 131 (66.5) | |||

| Increased financial stress, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Yes | 37 (23.6) | 24 (22.6) | 0.883 | 28 (25.7) | 10 (21.7) | 8 (14.8) | 15 (27.8) | 0.362 | 11 (16.7) | 50 (25.4) | 0.178 |

| No | 120 (76.4) | 82 (77.4) | 81 (74.3) | 36 (78.3) | 46 (85.2) | 39 (72.2) | 55 (83.3) | 147 (74.6) | |||

| Increased stress from home, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Yes | 37 (23.6) | 30 (28.3) | 0.391 | 31 (28.4) | 12 (26.1) | 9 (16.7) | 15 (27.8) | 0.412 | 13 (19.7) | 54 (27.4) | 0.254 |

| No | 120 (76.4) | 76 (71.7) | 78 (71.6) | 34 (73.9) | 45 (83.3) | 39 (72.2) | 53 (80.3) | 143 (72.6) | |||

| Feel horrified due to the COVID-19, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Yes | 83 (52.9) | 54 (50.9) | 0.802 | 67 (61.5) | 25 (54.3) | 16 (29.6) | 29 (53.7) | 0.002 | 29 (43.9) | 108 (54.8) | 0.155 |

| No | 74 (47.1) | 52 (49.1) | 42 (38.5) | 21 (45.7) | 38 (70.4) | 25 (46.3) | 37 (56.1) | 89 (45.2) | |||

| Feel apprehensive due to the COVID-19, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Yes | 83 (52.9) | 54 (50.9) | 0.802 | 63 (57.8) | 27 (58.7) | 15 (27.8) | 32 (59.3) | 0.001 | 33 (50.0) | 104 (52.8) | 0.776 |

| No | 74 (47.1) | 52 (49.1) | 46 (42.2) | 19 (41.3) | 39 (72.2) | 22 (40.7) | 33 (50.0) | 93 (47.2) | |||

| Feel helpless due to the COVID-19, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Yes | 74 (47.1) | 49 (46.2) | 0.900 | 56 (51.4) | 26 (56.5) | 17 (31.5) | 24 (44.4) | 0.049 | 32 (48.5) | 91 (46.2) | 0.777 |

| No | 83 (52.9) | 57 (53.8) | 53 (48.6) | 20 (43.5) | 37 (68.5) | 30 (55.6) | 34 (51.5) | 106 (53.8) | |||

| Sex (n = 263) | P-Value 1 | Age Group (Years) (n = 263) | P-Value 1 | Education Level (n = 263) | P-Value 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Females (n = 157) | Males (n = 106) | 18–30 (n = 109) | 31–40 (n = 46) | 41–50 (n = 54) | >50 (n = 54) | Secondary School (n = 66) | Higher Qualification (n = 197) | |||

| Getting support from friends, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Decreased | 6 (3.8) | 11 (10.4) | 0.080 | 2 (1.8) | 3 (6.5) | 8 (14.8) | 4 (7.5) | 0.028 | 4 (6.1) | 13 (6.6) | 0.709 |

| Same as before | 44 (28.0) | 32 (30.2) | 30 (27.5) | 11 (23.9) | 20 (37.0) | 15 (27.8) | 18 (27.3) | 58 (29.4) | |||

| Increased | 107 (68.2) | 63 (59.5) | 77 (70.7) | 32 (69.6) | 26 (47.2) | 35 (64.8) | 44 (66.7) | 126 (64.0) | |||

| Getting support from family members, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Decreased | 11 (7.0) | 14 (13.2) | 0.126 | 3 (2.7) | 3 (6.5) | 11 (20.4) | 8 (14.8) | 0.008 | 8 (12.1) | 17 (8.6) | 0.442 |

| Same as before | 39 (24.8) | 31 (29.2) | 29 (26.6) | 11 (23.9) | 21 (38.9) | 9 (16.7) | 20 (30.3) | 50 (25.4) | |||

| Increased | 107 (68.2) | 61 (57.5) | 77 (70.7) | 32 (69.6) | 22 (40.7) | 37 (68.5) | 38 (57.6) | 130 (66.0) | |||

| Shared feeling with family members, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Decreased | 18 (11.5) | 11 (10.4) | 0.563 | 5 (4.6) | 8 (17.4) | 8 (14.9) | 8 (14.8) | 0.027 | 6 (9.1) | 23 (11.7) | 0.535 |

| Same as before | 45 (28.7) | 37 (34.9) | 38 (34.9) | 9 (19.6) | 22 (40.7) | 13 (24.1) | 18 (27.3) | 64 (32.5) | |||

| Increased | 94 (59.8) | 58 (57.7) | 66 (60.5) | 29 (63.1) | 24 (44.5) | 33 (61.2) | 42 (63.6) | 110 (55.8) | |||

| Shared feeling with others when in blue, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Decreased | 20 (12.7) | 9 (8.5) | 0.195 | 5 (4.6) | 6 (13.0) | 12 (22.0) | 6 (11.2) | 0.011 | 10 (15.2) | 19 (9.6) | 0.452 |

| Same as before | 36 (22.9) | 34 (32.2) | 28 (25.7) | 8 (17.4) | 16 (29.6) | 18 (33.3) | 16 (24.2) | 54 (27.4) | |||

| Increased | 101 (64.3) | 63 (59.4) | 76 (69.8) | 32 (69.6) | 26 (48.2) | 30 (55.5) | 40 (60.6) | 124 (62.9) | |||

| Caring for family members’ feelings, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Decreased | 5 (3.2) | 4 (3.7) | 0.542 | 2 (1.8) | 1 (2.2) | 3 (5.6) | 3 (5.6) | 0.016 | 2 (3.0) | 7 (3.6) | 0.541 |

| Same as before | 26 (16.6) | 23 (21.7) | 18 (16.5) | 3 (6.5) | 15 (27.8) | 13 (24.1) | 15 (22.7) | 34 (17.3) | |||

| Increased | 126 (80.3) | 79 (84.6) | 89 (81.7) | 42 (91.3) | 36 (66.6) | 38 (70.4) | 49 (74.2) | 156 (79.2) | |||

| Sex (n = 263) | P-Value 1 | Age Group (Years) (n = 263) | P-Value 1 | Education Level (n = 263) | P-Value 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females (n = 157) | Males (n = 106) | 18–30 (n = 109) | 31–40 (n = 46) | 41–50 (n = 54) | >50 (n = 54) | Secondary School (n = 66) | Higher Qualification (n = 197) | ||||

| Pay attention to mental health, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Decreased | 5 (3.2) | 5 (4.7) | 0.539 | 1 (0.9) | 1 (2.2) | 6 (11.1) | 2 (3.7) | 0.050 | 4 (6.1) | 6 (3.0) | 0.286 |

| Same as before | 44 (28.0) | 31 (29.2) | 26 (23.9) | 12 (26.1) | 26 (48.1) | 11 (20.4) | 20 (30.3) | 55 (27.9) | |||

| Increased | 108 (68.8) | 70 (66.0) | 82 (75.2) | 33 (71.7) | 22 (40.7) | 41 (75.9) | 42 (63.6) | 136 (69.0) | |||

| Time spent to rest, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Decreased | 3 (1.9) | 4 (3.8) | 0.665 | 2 (1.8) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (1.9) | 3 (5.6) | 0.317 | 1 (1.5) | 6 (3.0) | 0.628 |

| Same as before | 56 (35.7) | 37 (34.9) | 36 (33.0) | 13 (28.3) | 30 (55.6) | 14 (25.9) | 23 (34.8) | 70 (35.5) | |||

| Increased | 98 (62.4) | 65 (61.3) | 71 (65.1) | 32 (69.6) | 23 (42.6) | 37 (68.5) | 42 (63.6) | 121 (61.4) | |||

| Time spent to relax, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Decreased | 14 (8.9) | 8 (7.5) | 0.906 | 4 (3.7) | 4 (8.7) | 2 (3.7) | 12 (22.2) | 0.011 | 8 (12.1) | 14 (7.1) | 0.305 |

| Same as before | 42 (26.8) | 30 (28.3) | 29 (26.6) | 12 (26.1) | 22 (40.7) | 9 (16.7) | 20 (30.3) | 52 (26.4) | |||

| Increased | 101 (64.3) | 68 (64.2) | 76 (69.7) | 30 (65.2) | 30 (55.6) | 33 (61.1) | 38 (57.6) | 131 (66.5) | |||

| Time spent to exercise, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Decreased | 4 (2.5) | 5 (4.7) | 0.206 | 3 (2.8) | 1 (2.2) | 2 (3.7) | 3 (5.6) | 0.793 | 4 (6.1) | 5 (2.5) | 0.588 |

| Same as before | 55 (35.0) | 42 (39.6) | 42 (38.5) | 11 (23.9) | 30 (55.6) | 14 (25.9) | 23 (34.8) | 74 (37.6) | |||

| Increased | 98 (62.4) | 59 (55.7) | 64 (58.7) | 34 (73.9) | 22 (40.7) | 37 (68.5) | 39 (59.1) | 118 (59.9) | |||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z.F. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health and Quality of Life among Local Residents in Liaoning Province, China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2381. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072381

Zhang Y, Ma ZF. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health and Quality of Life among Local Residents in Liaoning Province, China: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(7):2381. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072381

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yingfei, and Zheng Feei Ma. 2020. "Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health and Quality of Life among Local Residents in Liaoning Province, China: A Cross-Sectional Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 7: 2381. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072381

APA StyleZhang, Y., & Ma, Z. F. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health and Quality of Life among Local Residents in Liaoning Province, China: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2381. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072381