A Scoping Review of Children and Adolescents’ Active Travel in Ireland

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Summary of Past Reviews on Active Travel of Children and Adolescents

1.2. Overview of Irish Data on Active Travel of Children and Adolescents

1.3. Purpose of This Review

2. Materials and Methods

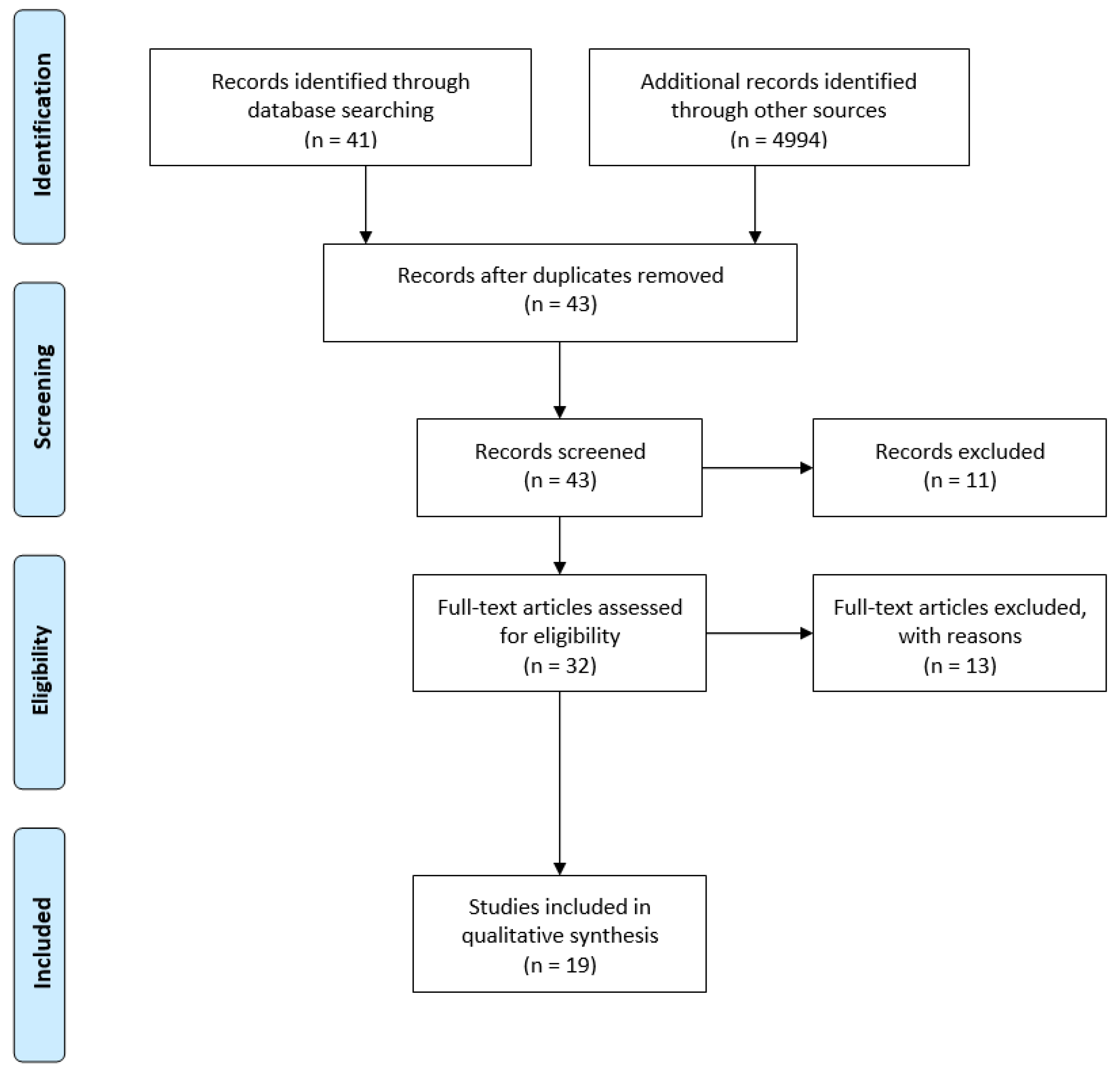

- Identifying relevant studies—a PubMed and Scopus database search was conducted. While these different databases provided existing published research evidence, Google Scholar and the Open Access to Irish Research database (RIAN) were also used in the context of this scoping review for identifying outstanding grey literature, such as theses, policies and reports.

- Study selection—by screening and assessing the data based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a set of publications was filtered down to a final selection of 19 studies eligible for the current review.

- Charting the data—each relevant document was screened and summarised, as the research team achieved consensus on the final list of references for the research.

2.1. Establishing Search Terms and Criteria to Identify Relevant Studies

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Charting the Data

3. Results

3.1. Methodological Characteristics of the Studies

3.2. Main Findings of the Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings from Research in the Republic of Ireland

4.2. Trends and Contributions of the Active Travel Research Methods in the Irish Context

4.3. Gaps and Areas of Opportunity for Active Travel Research in the Irish Context

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report; Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sluijs, E.V.; Fearne, V.; Mattocks, C.; Riddoch, C.; Griffin, S.; Ness, A. The contribution of active travel to children’s physical activity levels: Cross-sectional results from the ALSPAC study. Prev. Med. 2009, 48, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voss, C.; Winters, M.; Frazer, A.; McKay, H. School-travel by public transit: Rethinking active transportation. Prev. Med. Rep. 2015, 2, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larouche, R.; Saunders, T.J.; Faulkner, G.E.J.; Colley, R.; Tremblay, M. Associations Between Active School Transport and Physical Activity, Body Composition, and Cardiovascular Fitness: A Systematic Review of 68 Studies. J. Phys. Act. Health 2014, 11, 206–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumith, S.; Hallal, P.; Reis, R.; Kohl, H.W., 3rd. Worldwide prevalence of physical inactivity and its association with human development index in 76 countries. Prev. Med. 2011, 53, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallal, P.; Andersen, L.; Bull, F.; Guthold, R.; Haskell, W.; Ekelund, U.; Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. Global physical activity levels: Surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet 2012, 380, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, G.; Buliung, R.; Flora, P.; Fusco, C. Active school transport, physical activity levels and body weight of children and youth: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2009, 48, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, D.; Sallis, J.; Conway, T.; Cain, K.; McKenzie, T. Active Transportation to School Over 2 Years in Relation to Weight Status and Physical Activity. Obesity 2006, 14, 1771–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, N.; Brown, A.; Marchetti, L.; Pedroso, M.U.S. school travel, 2009: An assessment of trends. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 41, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buliung, R.N.; Mitra, R.; Faulkner, G. Active school transportation in the Greater Toronto Area, Canada: an exploration of trends in space and time (1986-2006). Prev. Med. 2009, 48, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammen, G.; Stone, M.; Faulkner, G.; Ramanathan, S.; Buliung, R.; O’Brien, C.; Kennedy, J. Active school travel: An evaluation of the Canadian school travel planning intervention. Prev. Med. 2014, 60, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grize, L.; Bringolf-Isler, B.; Martin, E.; Braun-Fahrländer, C. Trend in active transportation to school among Swiss school children and its associated factors: Three cross-sectional surveys 1994, 2000 and 2005. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timperio, A.; Ball, K.; Salmon, J.; Roberts, R.; Giles-Cort, B.; Simmons, D.; Baur, L.A.; Crawford, D. Personal, Family, Social, and Environmental Correlates of Active Commuting to School. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2006, 30, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tudor-Locke, C.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Popkin, B.M. Active commuting to school: An overlooked source of childrens’ physical activity? Sports Med. 2001, 31, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Ploeg, H.P.; Merom, D.; Corpuz, G.; Bauman, A.E. Trends in Australian children traveling to school 1971-2003: Burning petrol or carbohydrates? Prev. Med. 2008, 46, 60–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Ikeda, E.; Hinckson, E.; Duncan, S.; Maddison, R.; Meredith-Jones, K.; Walker, C.; Mandic, S. Results from New Zealand’s 2018 Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth. J. Phys. Act. Health 2018, 15, S390–S392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlin, A.; Murphy, M.H.; Gallagher, A.M. Do Interventions to Increase Walking Work? A Systematic Review of Interventions in Children and Adolescents. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, J.; Booth, M.; Phongsavan, P.; Murphy, N.; Timperio, A. Promoting Physical Activity Participation among Children and Adolescents. Epidemiol. Rev. 2007, 29, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, L.; Green, J.; Petticrew, M.; Steinbach, R.; Roberts, H. What Are the Health Benefits of Active Travel? A Systematic Review of Trials and Cohort Studies. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeppe, S.; Duncan, M.; Badland, H.; Oliver, M.; Curtis, C. Associations of children’s independent mobility and active travel with physical activity, sedentary behaviour and weight status: A systematic review. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2013, 16, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, C.; Powell, C.; Saunders, J.; O’Brien, W.; Murphy, M.; Duff, C.; Farmer, O.; Johnston, A.; Connolly, S.; Belton, S. The Children’s Sport Participation and Physical Activity Study 2018 (CSPPA 2018); Department of Physical Education and Sport Sciences, University of Limerick: Limerick, Ireland; Sport Ireland, and Healthy Ireland: Dublin, Ireland; Sport Northern Ireland: Belfast, Northern Ireland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, C.; Moyna, N.; Quinlan, A.; Tannehill, D.; Walsh, J. The Children’s Sport Participation and Physical Activity Study (CSPPA). Research Report No 1; School of Health and Human Performance, Dublin City University and The Irish Sports Council: Dublin, Ireland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Graf, C.; Beneke, R.; Bloch, W.; Bucksch, J.; Dordel, S.; Eiser, S.; Ferrari, N.; Koch, B.; Krug, S.; Lawrenz, W.; et al. Recommendations for Promoting Physical Activity for Children and Adolescents in Germany. A Consensus Statement. Obes. Facts 2014, 7, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Growing up Unequal: Gender and Socioeconomic Differences in Young People’s Health and Well-Being. Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children Study: International Report from the 2013/14 Survey; World Health Organization: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, M.; Parkinson, K.; Adamson, A.; Pearce, M.; Reilly, J.; Hughes, A.; Janssen, X.; Basterfield, L.; Reilly, J. Timing of the decline in physical activity in childhood and adolescence: Gateshead Millennium Cohort Study. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health & Department of Transport, Tourism and Sport. Healthy Ireland: Get Ireland Active—National Physical Activity Plan for Ireland; Department of Health & Department of Transport, Tourism and Sport: Dublin, Ireland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, D.; Murphy, M.; Carlin, A.; Coppinger, T.; Donnelly, A.; Dowd, K.; Keating, T.; Murphy, N.; Murtagh, E.; O’Brien, W.; et al. Results From Ireland North and South’s 2016 Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth. J. Phys. Act. Health 2016, 13, S183–S188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Keeffe, B.; O’Beirne, A. Children’s Independent Mobility on the island of Ireland; Get Ireland Active and Mary Immaculate College University of Limerick: Limerick, Ireland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, N.; Foley, E.; O’Gorman, D.; Moyna, N.; Woods, C. Active commuting to school: How far is too far? Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, N.; Woods, C. Neighborhood Perceptions and Active Commuting to School Among Adolescent Boys and Girls. J. Phys. Act. Health 2010, 7, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, M.; Woods, C. An Exploration of Children’s Perceptions and Enjoyment of School-Based Physical Activity and Physical Education. J. Phys. Act. Health 2011, 8, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahan, R.-A. Perceptions of the Built Environment and Active Travel in Children and Young People; Waterford Institute of Technology: Waterford, Ireland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Murtagh, E.; Murphy, M. Active Travel to School and Physical Activity Levels of Irish Primary Schoolchildren. Pediatric Exerc. Sci. 2011, 23, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, L.; Nic Gabhainn, S. HBSC Ireland 2010: Physical Activity, Active Travel and Exercise among Schoolchildren in Ireland 2010. Galway: Health Promotion Research Centre, NUI Galway. Short Report to Department of Children and Youth Affairs for the National Strategy for Research and Data on Children’s Lives 2011–2016; HBSC and Department of Health and Health Promotion Research Centre and NUI Galway: Galway, Ireland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, N. ; The HBSC Ireland Team. Active Travel among Schoolchildren in Ireland. HBSC Ireland Research Factsheet No. 22; HBSC and Department of Health and Health Promotion Research Centre and NUI Galway: Galway, Ireland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Delaney, P. Sport and Recreation Participation and Lifestyle Behaviours in Waterford City Adolescents; Coaching Ireland: Limerick, Ireland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, N.; Kelly, C.; Molcho, M.; Sixsmith, J.; Byrne, M.; Gabhainn, S.N. Investigating active travel to primary school in Ireland. Health Educ. 2014, 114, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, D.M.; Belton, S.; Coppinger, T.; Cullen, M.; Donnelly, A.; Dowd, K.; Keating, T.; Layte, R.; Murphy, M.; Murphy, N.; et al. Results from Ireland’s 2014 Report Card on Physical Activity in Children and Youth. J. Phys. Act. Health 2014, 11, S63–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMinn, D.; Rowe, D.A.; Murtagh, S.; Nelson, N.M.; Čuk, I.; Atiković, A.; Peček, M.; Breslin, G.; Murtagh, E.M.; Murphy, M.H. Psychosocial factors related to children’s active school travel: A comparison of two European regions . Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2014, 7, 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, C.; Nelson, N. An evaluation of distance estimation accuracy and its relationship to transport mode for the home-to-school journey by adolescents. J. Transp. Health 2014, 1, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambe, B. The Effectiveness of Active Travel Initiatives in Irish Provincial Towns: An Evaluation of a Quasi-Experimental Natural Experiment; Waterford Institute of Technology: Waterford, Ireland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- CSO. Census of Population 2016—Profile 6 Commuting in Ireland. Available online: https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-cp6ci/p6cii/p6stp/ (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- Murtagh, E.; Dempster, M.; Murphy, M. Determinants of uptake and maintenance of active commuting to school. Health Place 2016, 40, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambe, B.; Murphy, N.; Bauman, A. Active Travel to Primary Schools in Ireland: An Opportunistic Evaluation of a Natural Experiment. J. Phys. Act. Health 2017, 14, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Corder, K.; Sharp, S.; Atkin, A.; Griffin, S.; Jones, A.; Ekelund, U.; Sluijs, E.V. Change in objectively measured physical activity during the transition to adolescence. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumith, S.; Gigante, D.; Domingues, M.; Kohl, H.W., 3rd. Physical activity change during adolescence: A systematic review and a pooled analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 40, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherar, L.B.; Cumming, S.P.; Eisenmann, J.C.; Baxter-Jones, A.D.G.; Malina, R.M. Adolescent Biological Maturity and Physical Activity: Biology Meets Behavior. Pediatric Exerc. Sci. 2010, 22, 332–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, K.; Gilliland, J.; Hess, P.; Tucker, P.; Irwin, J.; He, M. The Influence of the Physical Environment and Sociodemographic Characteristics on Children’s Mode of Travel to and From School. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginja, S.; Arnott, B.; Araujo-Soares, V.; Namdeo, A.; McColl, E. Feasibility of an incentive scheme to promote active travel to school: A pilot cluster randomised trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2017, 3, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larouche, R.; Mammen, G.; Rowe, D.A.; Faulkner, G. Effectiveness of active school transport interventions: A systematic review and update. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, L.M.; Fry, D.; Merom, D.; Rissel, C.; Dirkis, H.; Balafas, A. Increasing active travel to school: Are we on the right track? A cluster randomised controlled trial from Sydney, Australia. Prev. Med. 2008, 47, 612–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klesges, L.M.; Baranowski, T.; Beech, B.; Cullen, K.; Murray, D.M.; Rochon, J.; Pratt, C. Social desirability bias in self-reported dietary, physical activity and weight concerns measures in 8- to 10-year-old African-American girls: Results from the Girls health Enrichment Multisite Studies (GEMS). Prev. Med. 2004, 38, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, M.; MacPhail, A. Young People’s Voices in Physical Education and Youth Sport; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Public Health in Ireland. Active Travel—Healthy Lives; Institute of Public Health in Ireland: Dublin, Ireland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1986. (Original work published 1979). [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Making Human Beings Human; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kyttä, M.; Oliver, M.; Ikeda, E.; Ahmadi, E.; Omiya, I.; Laatikainen, T. Children as urbanites: Mapping the affordances and behavior settings of urban environments for Finnish and Japanese children. Child. Geogr. 2018, 16, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Charting Dimension | Charting Guideline |

|---|---|

| Study Design | Refer if research was intervention, multiple baseline, case-study, etc. |

| Population/Sample | Refer sample size, key demographics, and highlight if cohort is primary or secondary education level. |

| Method | Refer if data were self-reported or objectively measured, with the specific tools if relevant. |

| Active Travel concept(s) and theoretical frameworks | Identify which concept was used (e.g., Active Travel, Active Transport, Active Commuting) and what theoretical frameworks explicitly informed the study. |

| Summary of Findings | Summarise only disaggregated data related to active travel in the context of the Republic of Ireland. |

| Document | Study Design | Population/Sample (n; % of Girls; Mean Age, Age Range; Other) | Method | Active Travel Concept(s) and Theoretical Frameworks | Summary of Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nelson et al. (2008) [31] | Cross-sectional | n = 4,013 adolescents; 48.1% girls; 16.1 years, 15–17 years. | Self-report questionnaires. | Active commuting; Mode of transport, barriers, distance. No theoretical framework mentioned. | 33% walked or cycled to school; A higher proportion of males than females commuted actively (41.0% vs. 33.8%); Adolescents living in more densely populated areas had greater odds of active commuting than those in the most sparsely populated areas; Most walkers lived within 1.5 miles and cyclists within 2.5 miles of school; A 1-mile increase in distance decreased the odds of active commuting by 71%. |

| Nelson and Woods (2010) [32] | Cross-sectional (from Take PART study: PA research for teenagers) | n = 2159 adolescents; 47.1% girls; 16.0 years, 15–17 years. | Self-report questionnaires. | Active commuting (cycle, walking); Inactive commuting (car, bus or train); Duration, frequency. Mentions the Social-Ecological theory. | Most adolescents chose active modes of travel (61.3% walked, 8.7% cycled); boys were more likely to cycle to school (15.4% vs. 1.2%) and girls were more likely to travel by car (27.0% vs. 18.3%). |

| Woods et al. (2010) [22] | Cross-sectional (Children’s Sport Participation and Physical Activity (CSPPA) study, Nationally representative Irish cluster sample) | n = 1275 primary school students; 45% female; 11.4 years, 10–13 years; n = 4122 post-primary school students; 52% female; 14.5 years, 12–18 years. | Self-report questionnaires; ActiGraph, accelerometers and pedometers. | Active travel; Type of transport, duration, distance. No theoretical framework mentioned. | 38% (31% primary, 40% post-primary) of children and youth walked or cycled to school in 2009; journey durations were on average 15 min for active commuters; No gender differences existed for active commuting at primary school; post-primary females were less likely to actively commute than males (38% vs. 43%, p < 0.01); 1% of primary pupils and 3% of post-primary pupils cycled to school; Main barriers: Distance (37% primary, 54% post-primary); Time (13% and 19%); Traffic-related danger for primary (13%); and Convenience for post-primary (8%). |

| Coulter and Woods (2011) [33] | Cross-sectional | n = 605 students; 44% female; 8.8 years, 5–15 years. Other: All students from 1 single, large, urban, mixed primary school in Dublin. | Self-report questionnaires. | Active Commuting (as walking or cycling to school on the previous day); Inactive commuting (traveling by bus or car); Estimation of residential distance from School. No theoretical framework mentioned. | 39.9% of children actively commuted to school (37.8% walk, 1.1% cycle); 40.7% of children actively commuting from school (39% walk, 1.7% cycle); 56.6% of primary aged children are driven to school; 28.9% live within 1 km of the school but are inactive commuters; Gender did not predict inactive commuting; Compared with younger children (5–6 years), the odds of inactively commuting for every year increase in age decreases by approximately 24%. |

| Gahan (2011) [34] | Cross-sectional | n = 89 adolescents; 6–15 years; 48.3% female (returned questionnaires) n = 44 adolescents; 6–15 years; 47.7% girls (participated in the workshop). | Self-report questionnaires; Workshop; Walkability audit. | Active travel; Type of transport, frequency. Mentions social ecological frameworks. | Most commonly used mode of transport by children and young people: 1. Parents’ car (357 times; 2. Walking (205 times); 3. Cycling (80 times); Most commonly use of walking and cycling is going to school, shop, friend’s house; Main barriers: no place to walk (56%); difficulty crossing the road (57%); drivers do not behave well (60%); neighbourhood is not a nice place to live (35%). |

| Murtagh and Murphy (2011) [35] | Cross-sectional | n = 140 children; 39.3% female; 9.9 years, 9–11 years. | Self-report questionnaires; Objective pedometers for step count. | Active travel; Active commute. No theoretical framework mentioned. | 62.1% travelled by car, and 36.4% walked to school; Children who walked or cycled to school had higher daily step counts than those who travelled by passive modes (16,118 ± 5757 vs. 13,363 ± 5332 steps). |

| Sullivan and Nic Gabhainn (2012) [36] | Cross-sectional (From the national research study of Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC)) | n = 16,060 students; 49% girls; 10–17 years. From 3rd class in primary school to 5th year in post-primary school. Other: Nationally representative Irish cluster sample. | Self-report questionnaires. | Active travel; Type of transport, duration, frequency (every day). No theoretical framework mentioned. | Walk: boys 23.9%, girls 23.5%; 10–11 years 26.0%, 12–14 years 23.7%, 15–17 years 22.6%; SC1–2 19.9%, SC3–4 23.2%, SC5–6 27.0%; Cycle: boys 3.7%, girls 0.8%; 10–11 years 4.0%, 12–14 years 2.5%, 15–17 years 1.6%; SC1–2 1.8%, SC3–4 2.5%, SC5-6 3.2%. |

| Clarke and The HBSC Ireland Team (2013) [37] | Cross-sectional (factsheet) | Sample from the HBSC research study; n = 12,661 (10–17 years). | Self-report questionnaires. | Travel to school by walking or cycling for the main part of their journey. No theoretical framework mentioned. | 26.5% of schoolchildren in Ireland reported actively travelling to school, 28.1% boys, 24.7% girls; Boys, younger children, children from lower social classes, and children living in urban areas were more likely to report actively travelling to school; Children who reported actively travelling to school were more likely to report excellent health, to be very happy, to be more active. |

| Delaney (2013) [38] | Cross-sectional | n = 2877 participants; 53% girls; 12–20 years. | Self-report questionnaires. | Active travel; Distance to school. No theoretical framework mentioned. | 24% used active transport as a means of travel to school; Most individuals, who use active transport, live within 1 mile of their school; The percentages of those using active travel dropped the further individuals live from their respective school; Those who were active in sport and recreation activities appeared to be greater users of active travel. |

| Daniels et al. (2014) [39] | Cross-sectional. | n = 73 children; 60.3% female; 11–13 years. | Self-report questionnaires; Workshop. | Active School Travel (walking and cycling). No theoretical framework mentioned. | Non-active travel = 69.9%; 54.5% who reported they actively travelled do so 4-5 days per week; 86.3% reported owning a bicycle; None of the active travellers reported travelling to school with parents; they were more likely to travel to school with friends compared to children who do not travel actively (59.1% vs. 9.8 %); Main promoters: 1. Company/Parents and Community; 2. School infrastructure/School; 3. Distance/Parents; 4. Physical Health/Parents, Self, Health Professionals; 5. Equipment/Parents, Self, School, Government; Main barriers: 1. Distance/Community and Parents; 2. Weather/Government and Weatherman; 3. Lifestyle/Parents; 4. Road infrastructure and planning/Government, School, Builders; 5. Strangers/Community, Parents, Government, Builders. |

| Harrington et al. (2014) [40] | Report (including both longitudinal and cross-sectional reports and studies) | HBSC: n = 13,611 (11–15 years; 2013–2014 waves—representative sample). Growing Up in Ireland (GUI) Infant and Child Cohorts: n ≈ 9,000 children and their caregivers; (Wave 3 of the infant cohort, followed up at age 5 years); n ≈ 7400 children; 2011–2012, from Wave 2 of the child cohort, followed up at age 13 years. | Children and parents self-report questionnaires. | Percentage of children reporting active transport to or from school each day. No theoretical framework mentioned. | Active transportation grade D (meaning 21% to 40% meet the defined benchmark); Data from larger studies provided evidence of children/adolescents succeeding with 20% to 29%; Sex gaps evident for other indicators may not be as obvious for active transport; Children from rural areas were less likely to active commute than their urban counterparts. |

| McMinn et al. (2014) [41] | Cross-sectional (including 5 countries) | n = 136; 8.7 years, 69.9 girls. | Self-report questionnaires. | Active commuting; Walkers. Mentions the Theory of Planned Behaviour. | Republic of Ireland 42.0% walkers (i.e., those participants who categorized themselves as being in the action or maintenance stages, according to Theory of Planned Behaviour). |

| Woods and Nelson (2014) [42] | Cross-sectional | n = 199 adolescents; 42.3% girls; 15.9 years, 15–17 years. | Self-report questionnaires; Objective distance (map-measured). | Distance, Time and Mode of active travel (walk, cycle, car, bus). No theoretical framework mentioned. | Mode of transport: walk 72.4%, car 21.1%, bus 6.5%; Distance travelled by active commuters 1.3 km - perceived distance 1.4 km; by inactive 1.4 km, perceived 2.7 km; Active commuters were accurate in their perception of distance travelled; For passive commuters, the average actual distance (1350 m) travelled to school was significantly shorter than their perception of this distance. |

| Lambe (2015) [43] | Community-wide intervention study collected at 2 time-points (May 2011 and May 2013). | Study 1: Primary Education: 5th–6th class students (n = 1457) in 21 primary schools (9 in intervention town 1; 5 in intervention town 2; and 7 in the control town). Study 2: Secondary Education: 1st, 2nd, the class students in 15 secondary schools (6 schools in intervention town 1; 5 in intervention town 2; and 4 in the control town). | Self-report questionnaires. | Travel mode to school; Actual and Preferred; Awareness of community interventions on active travel. Mentions ecological models. | Study 1: At baseline, 25.6% and 3.7% of the total sample walked or cycled to school; boys were more likely to cycle than girls; Greater proportions of students walked or cycled home from school than to school (39.3% vs. 29.3%); Car was the most common mode of travel to or from school in each town (60.8% and 49.1%, respectively); Overall, the intervention had no effect on active travel behaviour. Study 2: 17% of the total sample actively commuted to school and distance was a key factor; 64% of the total sample lived more than 3km from their school and of these, only 7% actively commuted to school; Boys were more likely to engage in active travel to school but car travel was still the most common (62%) and preferred (47%) mode of travel for all; Overall, awareness of the community-wide active travel campaign increased by 13% and 20% in intervention towns 1 and 2. |

| Central Statistics Office (2016) [44] | Cross-sectional (Census 2016, national population survey) | n = 896,575 commuters (546,614 primary commuters; 349,961 secondary commuters). Adult respondents. | Self-report questionnaires. | Self-propelled transport (walking - cycling). No theoretical framework mentioned. | Primary Education: Active transport decreased from 49.5% in 1986 to 24.8% in 2016. In 2016, 22% of Irish vs. 38% non-Irish walk; 1% of Irish and 2% of non-Irish cycle. Secondary Education: Walking decreased from 31.9% in 1986 to 21.2% in 2016; Cycling decreased from 15.3% in 1986 to 2.1% in 2016; Just over a fifth of secondary students walked to school (74,111) up slightly from 73,946 (0.2%) in 2011, but as a percentage of commuters, down almost 2% since 2011; 2016 saw the reversal of this trend with a 10.5% increase since 2011, bringing the numbers of secondary students taking to their bikes to over 7,000. |

| Harrington et al. (2016) [27] | Report (including both longitudinal and cross-sectional reports and studies) | Sample from: Ireland’s 2016 Report Card Growing Up in Ireland (GUI) Infant and Child Cohorts; HBSC; Children’s Sport Participation and Physical Activity (CSPPA Plus)/ | Self-report questionnaires. Interviews. | Active transportation. No theoretical framework mentioned. | Active Transportation - Grade D (The grade for each indicator is based on the percentage of children and youth meeting a defined benchmark, D is 21% to 40%); 23% males, 25% females used of active transport in a local sample of 2877. |

| Murtagh, Dempster, and Murphy (2016) [45] | Cross-sectional | Sample from “Growing Up in Ireland” study; Wave 1 n = 8502 (9 years); Wave 2 n = 7479 (13 years). | Interviews. Self-report questionnaires. Anthropometric measures. | Active school travel (uptake and maintenance; dropped out;); Walking and cycling classified as active; Travel mode. Mentions the Bioecological Model. | Within a 4 years period, active travel decreased from 25% to 20%; More likely to uptake or maintain if living in Urban; Less distance affected uptake and maintenance. Walking: Wave1 = 23.8% to Wave2 = 17.8% Cycling: Wave1 = 1.3% to Wave2 = 2.0%; At 9 years of age 75% of children travelled to school using passive travel modes; At 13 years 66% of students maintained passive commuting modes, 14% switched from active to passive commuting, 11% maintained active commuting, and 9% took up active commuting; Overall, at 13 years, 80.2% of the sample travelled to school using passive modes. |

| Lambe et al. (2017) [46] | Repeat cross-sectional study of a natural experiment | n = 1459 5th–6th class students from all the 21 schools in 3 towns (n = 1038 students in 2 intervention towns; n = 419 students in 1 control town). | Self-report questionnaires. | Actual and preferred mode of travel to and from school; Awareness of the active travel campaign in school and town; Percentage of children that walk or cycle to school. No theoretical framework mentioned. | Baseline: Total sample, car use (60.8%), cycle (3.7%), walk (25.6%); Walk or cycle from school (39.3%), to school (29.3%); Bicycle ownership (>85%); Preference for walking and cycling to school was considerably higher than preference for being driven. Intervention impact: There was no overall intervention effect detected for active travel to or from school. To school (Town1: pre 33.9%, post 31.2%; Town 2: pre 28.8%, post 33.0%); From school (Town1: pre 41.0%, post 39.5%; Town 2: pre 37.4%, post 38.4%). Some evidence of an effect for males in intervention town 2 (increase of 14% in active travel home from school). |

| Woods et al. (2018) [21] | Cross-sectional (CSPPA study - Nationally representative Irish cluster sample) | n = 1103 Primary school students, 56% female; 11.43 years (n = 3594 Post-primary school students; 54% female; 14.11 years; 45% male). | Self-report questionnaires ActiGraph accelerometers and pedometers. | Active travel and active commuting; Type of transport, duration, distance. No theoretical framework mentioned. | 42% primary, 40% post-primary school children reported walking or cycling to or from school; 2.2% reported cycling to or from school; At primary school level, more 6th class pupils reported actively commuting than 5th class pupils (47% vs. 36%); At post primary school level, active commuting peaked during 4th year (61%), but was lowest among 6th year pupils (23%); Main barriers: 1. Not enough safe places to cross the road for primary school students (26%), distance being too far for post-primary students (32%); 2. Heavy schoolbags for primary and post-primary school students (22% and 28%, respectively). |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Costa, J.; Adamakis, M.; O’Brien, W.; Martins, J. A Scoping Review of Children and Adolescents’ Active Travel in Ireland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2016. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17062016

Costa J, Adamakis M, O’Brien W, Martins J. A Scoping Review of Children and Adolescents’ Active Travel in Ireland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(6):2016. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17062016

Chicago/Turabian StyleCosta, João, Manolis Adamakis, Wesley O’Brien, and João Martins. 2020. "A Scoping Review of Children and Adolescents’ Active Travel in Ireland" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 6: 2016. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17062016

APA StyleCosta, J., Adamakis, M., O’Brien, W., & Martins, J. (2020). A Scoping Review of Children and Adolescents’ Active Travel in Ireland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(6), 2016. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17062016