Women’s Well-Being and Rural Development in Depopulated Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

- (1)

- A needs analysis conducted on the basis of open interviews.

- (2)

- A quantitative analysis performed by administering a questionnaire developed according to the results obtained in Stage 1. The data obtained in this phase had the greatest weight in all the data processing and in general in the whole study.

- (3)

- A qualitative analysis based on semi-structured interviews with a view to supplementing the data collected in Stage 2. These data have served to complement the information that was not entirely complete with the questionnaire designed, due to the limitations of the closed-ended items.

2.2. Participants

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Data Analysis

- Data preparation. The interviews, which had been previously recorded with the prior consent of the interviewees, were transcribed.

- Developing a category system. A combination of inductive and deductive approaches was employed to analyse the data.

- Coding with the Atlas-ti computer software (Version 7.2, Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlín, Germany).

3. Results

3.1. Work Environment

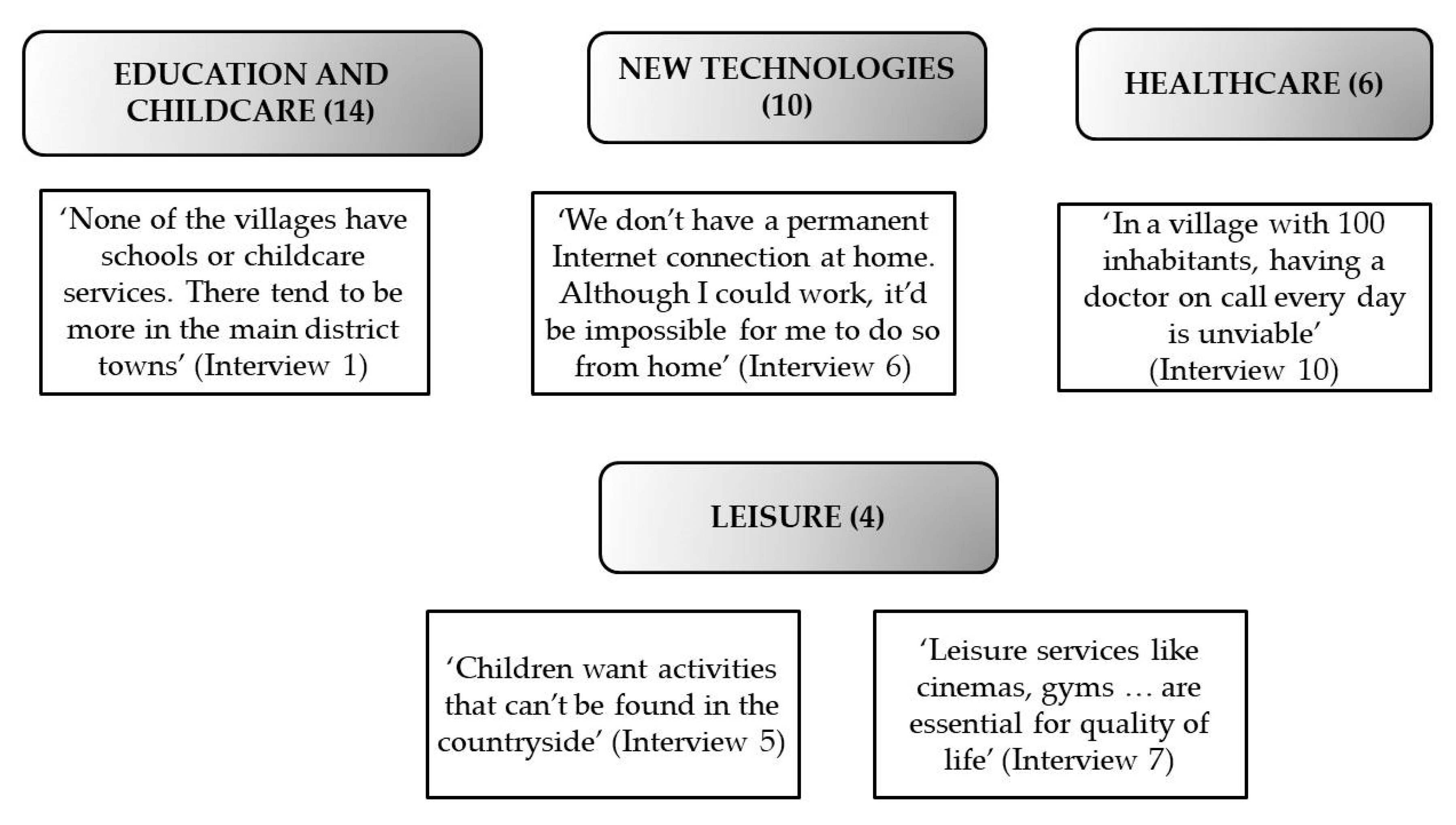

3.2. Services

3.3. Personal Sphere

3.4. Family Setting

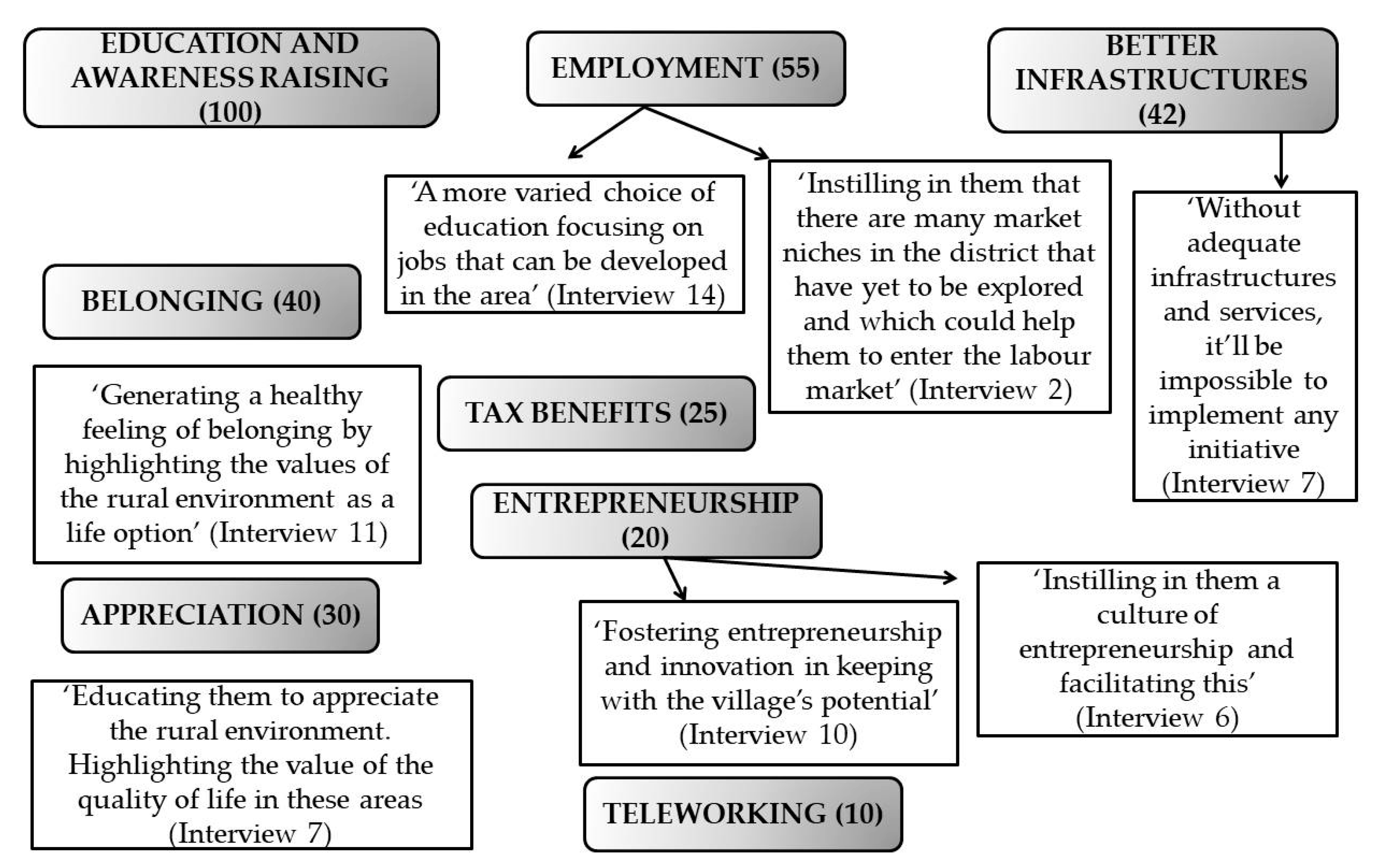

3.5. Socio-Educational Measures Aimed at Curbing the Exodus of Rural Women

- (1)

- They contended that schools were crucial for resolving the serious problem of dissatisfaction and the subsequent drop in the female population in the Celtiberian Highlands. These schools are of huge importance for the population, in general, and for women, in particular, basically for:

- Firstly, they facilitate the reconciliation of work and family life, which is essential for women who, first and foremost, care for children and the aged (Interview 1).

- Secondly, the lack of schools has a dissuasive effect on men and women who want to start a family in a village, because for them the education of their offspring is a basic service (Interview 19).

- Lastly, schools as socialising agents play an important role in the non-sexist and non-discriminatory education of women. Education should be a strategic resource for their personal and social emancipation and, by extension, their well-being. According to the interviewees, the first point of intervention should be women’s awareness raising and education (Interview 20). Many women hold that a good education is the only way of feeling valued and appreciated in the society in which they live. Therefore, occupational training programmes that are adapted to the labour demands of the rural area in question and which create more job opportunities should be designed.

- (2)

- Improvement of infrastructure. In many cases, the aforementioned deficits in telecommunication services oblige locals to go to a certain area of their villages, usually the highest and most distant point, to access services like 3G (3rd generation). On the one hand, this prevents them from taking distance learning courses or leveraging the opportunities offered by teleworking. Additionally, on the other, due to the lack of broadband services they are unable to download programs, tutorials or training videos, or to handle their own logistics to create and run a company remotely in real time. Technological advances have allowed for integration of rural population into a digital society in which the geographical location of workers is of little importance. With online work, the controversy that the higher the education, the higher the migration level could be surmounted, since “it’s impossible to engage in a job for which you’ve been trained in the rural environment” (Interview 16). With respect to the transport network, the huge distances involved, plus the bad state of the roads, make travelling from one area to another very onerous indeed. By way of example, the lack of adequate road connections turns something as normal as driving to a health centre into an authentic odyssey. In the case of pregnant women or those with children or aged parents (the age groups at greatest risk) in their care, the situation is even more critical: “The mere thought of suffering a serious health problem and not being treated in time is a cause of anxiety for many” (Interview 17).

- (3)

- Improving job opportunities and working conditions. The proposals put forward by the respondents and interviewees included tax benefits and positive discrimination measures, plus supporting entrepreneurship and teleworking.

4. Discussion

5. Limits of the Study and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary File 1Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ElEconomista.es. La Laponia Del Sur: Una parte De España Que Se Desangra Por La Despoblación. Available online: https://www.eleconomista.es/empresas-finanzas/agro/noticias/8111890/01/17/La-Laponia-de-Sur-parte-de-Espana-que-se-desangra-por-la-despoblacion.html (accessed on 7 December 2019).

- Sánchez-Muros, S.P.; Jiménez, M.L. Mujeres rurales y participación social: Análisis del asociacionismo femenino en la provincia de Granada (España). Cuad. Desarro. Rural 2013, 10, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarero, L.; Sampedro, R. Why are women leaving? The mobility continuum as an explanation of rural masculinization process. Rev. Esp. Investig. Sociol. 2008, 124, 73–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarero, L. Los patrimonios de la despoblación: La diversidad del vacío. Rev. PH 2019, 98, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, N.; Trillo, D. Women, rural environment and entrepreneurship. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 161, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobierno de España. Plan Estratégico De Igualdad De Género En El Medio Rural De Extremadura (2017–2020). Available online: http://www.juntaex.es/filescms/con03/uploaded_files/SectoresTematicos/DesarrolloRural/DiversificacionYDesarrolloRural/PlanEstrategicoDeIgualdadDeGeneroEnElMedioRural.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2019).

- Hillemeier, M.M.; Weisman, C.S.; Chase, G.A.; Dyer, A.M. Mental Health Status Among Rural Women of Reproductive Age: Findings From the Central Pennsylvania Women’s Health Study. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 1271–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice; Summary Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004; Available online: https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/en/promoting_mhh.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2019).

- Kelly, D.; Steiner, A.; Mazzei, M.; Baker, R. Filling a void? The role of social Enterprise in addressing social isolation and loneliness in rural communities. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 70, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henning-Smith, C.; Moscovice, I.; Kozhimannil, K. Differences in Social Isolation and Its Relationship to Health by Rurality. J. Rural Health 2019, 35, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mental Health Europe. From Exclusion to Inclusion. The Way to Promoting Social Inclusion of People with Mental Health Problems in Europe; MHE: Linz, Austria, 2009; Available online: https://consaludmental.org/publicaciones/Delaexclusionalainclusion.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2019).

- Panazzola, P.; Leipert, B. Exploring mental health issues of rural senior women residing in southwestern Ontario, Canada: A secondary analysis photovoice study. Rural Remote Health 2013, 13, 1–13. Available online: www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/2320 (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- Harvey, D. Conceptualising the mental health of rural women: A social work and health promotion perspective. Rural Soc. 2009, 19, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzaniga, J.; Suso, A. Salud Mental E Inclusión Social. Situación Actual Y Recomendaciones Contra El Estigma; Confederación SALUD MENTAL ESPAÑA: Madrid, Spain, 2015; Available online: https://consaludmental.org/publicaciones/Salud-Mental-inclusion-social-estigma.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2019).

- Pham, T.; Nguyen, N.T.T.; ChieuTo, S.B.; Pham, T.L.; Nguyen, T.X.; Nguyen, H.; Nguyen, H.T.T.; Nguyen, T.N.; Nguyen, T.H.T.; Nguyen, Q.N.; et al. Gender Differences in Quality of Life and Health Services Utilization among Elderly People in Rural Vietnam. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreta-Herrera, R.; López-Calle, C.; Gordón-Villalba, P.; Ortíz-Ochoa, W.; Gaibor-González, I. Satisfaction with Life, Psychological and Social Well-being as Predictors of Mental Health in Ecuadorians. Actual. Psicol. 2018, 32, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization as Adopted by the International Health Conference; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; Available online: https://www.who.int/governance/eb/who_constitution_en.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2019).

- Mascheroni, P.; Riella, A. La vulnerabilidad laboral de las mujeres en áreas rurales. Reflexiones sobre el caso Uruguayo. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2016, 29, 57–72. Available online: http://www.scielo.edu.uy/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0797-55382016000200004&lng=es&nrm=iso (accessed on 7 January 2020).

- Bogar, S.; Ganos, E.; Hoormann, K.; Bub-Standal, C.; Beyer, K. Raising rural women’s voices: From self-silencing to self-expression. J. Women Aging 2017, 29, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio De Sanidad, Servicios Sociales E Igualdad. Plan Para La Promoción De Las Mujeres Del Medio Rural. Available online: http://www.igualdadgenerofondoscomunitarios.es/Documentos/documentacion/doc_igualdad/plan_mujeres_medio_rural_15_18.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2019).

- RNDR. El Futuro Se Escribe En Femenino. Available online: http://www.redruralnacional.es/documents/10182/30117/1467879538047_upload_00055765.pdf/d55a32e9-c336-45a6-9485-ba1883391c05 (accessed on 5 December 2019).

- Salamaña, I.; Baylina, M.; Porto, A.M.; Villarino, M. Dones, trajectòries de vida i noves ruralitats. Doc. Anal. Geogr. 2016, 62, 661–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidickienė, D. Attractiveness of Rural Areas for Young, Educated Women in Post-Industrial Society. East. Eur. Countrys. 2017, 23, 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patino-Alonso, M.C.; Vicente-Galindo, M.P.; Galindo-Villardón, M.P.; Vicente-Villardón, J.L. Multivariate profile of women who work in rural settings in Salamanca, Spain. Am. J. Sociol. 2015, 52, 806–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley 45/2007, De 13 De Diciembre, Para El Desarrollo Sostenible Del Medio Rural. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2007-21493 (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- PNDR. Programa Nacional de Desarrollo Rural. Available online: http://www.redruralnacional.es/documents/10182/171010/Programa_Nacional_2014ES06RDNP001_4_2_es.pdf/ab68556c-499d-4e8a-944e-c66790529de0 (accessed on 7 December 2019).

- Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Medio Rural y Marino. Diagnóstico De La Igualdad De Género En El Medio Rural. Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/desarrollo-rural/temas/igualdad_genero_y_des_sostenible/DIAGN%C3%93STICO%20COMPLETO%20BAJA_tcm30-101391.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2019).

- Leipert, B.D.; George, M.A. Determinants of Rural Women’s Health: A Qualitative Study in Southwest Ontario. J. Rural Health 2008, 24, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. Motivation and Personality, 3rd ed.; Harper & Row Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación. Grupos de Acción Local (GAL). Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/cartografia-y-sig/ide/descargas/desarrollo-rural/gal.aspx (accessed on 17 December 2019).

- Larsson, A.; Westerberg, M.; Karlqvist, L.; Gard, G. Teamwork and Safety Climate in Homecare: A Mixed Method Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uprichard, E.; Dawney, L. Data Diffraction: Challenging Data Integration in Mixed Methods Research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2019, 13, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Velzen, J.H. Students’ General Knowledge of the Learning Process: A Mixed Methods Study Illustrating Integrated Data Collection and Data Consolidation. J. Mix. Methods Res 2018, 12, 182–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RRN. Grupos de Acción Local. Available online: http://www.redruralnacional.es/leader/grupos-de-accion-local (accessed on 7 December 2019).

- Valles, M.S. Entrevistas Cualitativas, 2nd ed.; Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas: Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, M.J. La Investigación Educativa. Claves Teóricas; Mc Graw-Hill: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Weller, S.C.; Vickers, B.; Bernard, H.R.; Blackburn, A.M.; Borgatti, S.; Gravlee, C.C.; Johnson, J.C. Open-ended interview questions and saturation. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz, C. Investigación cualitativa y análisis de contenido temático. Orientación intelectual de revista Universum. Rev. Gen. Inf. Doc. 2018, 28, 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C. Interview Techniques for UX Practioners. A User-Centered Design Method; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wildemuth, B.M. Applications of Social Research Methods to Questions in Information and Library Science; Libraries Unlimited: Santa Barbara, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonafé, J. La mujer es vital para el mundo rural, sin mujeres no hay pueblos. Desarro. Rural Sosten. 2018, 6–9. Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/ministerio/pags/biblioteca/revistas/pdf_DRS%5CRRN35_completa.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Gálvez-Muñoz, L.; Matus- López, M. Trabajo, Bienestar Y Desarrollo De Las Mujeres En El Ámbito Rural Andaluz: Estudio Para El Diseño De Políticas De Igualdad Y Desarrollo. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/libro?codigo=709794&orden=0&info=open_link_libro (accessed on 11 December 2019).

- Cornish, H.; Walls, H.; Ndirangu, R.; Ogbureke, N.; Bah, O.M.; Favour Tom-Kargbo, J.; Dimoh, M.; Ranganathan, M. Women’s economic empowerment and health related decision-making in rural Sierra Leone. Cult. Health Sex. 2019, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franić, R.; Kovačićek, T. The Professional Status of Rural Women in the EU; European Parliament: Burssels, Belgium, 2019; Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2019/608868/IPOL_STU(2019)608868_EN.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2019).

- Rabaneque, G. Mujer Rural, Salud Y Calidad De Vida. Ruralia 1999, 5–8. Available online: https://www.masdenoguera.coop/sites/default/files/ruralia-3.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2019).

- Soto, P.; Fawaz, M.J. Ser mujer microempresaria en el medio rural. Espacios, experiencias y significados. Cuad. Desarro. Rural 2016, 13, 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Province | No. of Members of the Grupos de Desarrollo Rural (GDRs) | % of the Total | Sample Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burgos | 12 | 4.29 | 7 |

| Segovia | 23 | 8.21 | 14 |

| Soria | 18 | 6.43 | 11 |

| Guadalajara | 56 | 20 | 33 |

| Cuenca | 56 | 20 | 33 |

| Teruel | 6 | 2.14 | 4 |

| Saragossa | 81 | 28.3 | 48 |

| Castellon and Valencia | 20 | 7.14 | 12 |

| La Rioja | 8 | 2.86 | 5 |

| Total | 280 | 100 | 165 |

| Categories | Indicators | |

|---|---|---|

| Identification data | Gender | Male/Female |

| Territorial scope | Scope of the GDR | |

| Projects | Aimed exclusively at women | |

| Work environment | Employment sectors by gender | Agriculture Building Services Administration |

| Motivation | Occupational activity in the rural setting Links to other women Entrepreneurship in small businesses Participation in family concerns | |

| Training | Gender and university education Aim of migration Objective of the traditional occupational activity of men | |

| Services | Education/childcare | Fostering job equality Fostering women’s empowerment |

| New technologies | Internet Telephone coverage | |

| Health | Medical Services Health care | |

| Leisure | For children Difference men/women | |

| Personal sphere | Self-perception | Contributions to sustainable development Inferiority complex towards urban women in the workplace Inferiority complex towards urban women in the social setting |

| Entertainment | Gender and leisure activities | |

| Family setting | Reconciling work and family life | Social support Subsidies/services |

| Sexual division of roles | Work Caring for aging parents Caring for young family members | |

| Socio-educational measures for improving the level of satisfaction of women and for favouring sustainable rural development | Training/awareness raising | Needs of the area |

| Job opportunities | ||

| Assessment of the area | ||

| Professional training | ||

| Improving infrastructures | New technologies Transport | |

| Job opportunities | Tax benefits | |

| Positive discrimination measures | ||

| Entrepreneurship | ||

| Teleworking |

| Dimension | KMO Test | Bartlett’s Test | Factor Loading Ranging (These Values Refer to the Load of Each of the Questionnaire Items on Each Factor, Is Not the Range) | % Variance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X2 | gl | Sig. | ||||

| 1 | 0.788 | 986.477 | 28 | 0.000 | 0.792-0.438-0.640-0.813-0.681-0.687-0.847-0.818 | 52.190 |

| 2 | 0.830 | 310.629 | 15 | 0.000 | 0.750-0.827-0.723-0.509-0.718-0.775 | 52.429 |

| 3 | 0.763 | 620.805 | 36 | 0.000 | 0.620-0.663-0.746-0.654-0.650-0.506-0.581-0.654-0.603 | 40.151 |

| 4 | 0.846 | 745.545 | 66 | 0.000 | 0.490-0.618-0.608-0.628-0.597-0.667-0.703-0.736-0.620-0.678-0.701-0.671 | 41.745 |

| Place of Work | Average Range | Kruskal–Wallis H | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A growing number of women pursue higher education to have access to jobs outside their place of residence | City | 36.50 | 25.082 |

| Main town of a district | 77.79 | ||

| Rural district | 96.51 |

| Is the GDR Running Any Rural Development Projects Aimed Exclusively at Women? | Average Range | Mann Whitney U | |

|---|---|---|---|

| There are a growing number of women inclined to work in the area | Yes | 105.53 | 1667.000 |

| No | 73.25 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cobano-Delgado, V.; Llorent-Bedmar, V. Women’s Well-Being and Rural Development in Depopulated Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1966. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17061966

Cobano-Delgado V, Llorent-Bedmar V. Women’s Well-Being and Rural Development in Depopulated Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(6):1966. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17061966

Chicago/Turabian StyleCobano-Delgado, Veronica, and Vicente Llorent-Bedmar. 2020. "Women’s Well-Being and Rural Development in Depopulated Spain" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 6: 1966. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17061966

APA StyleCobano-Delgado, V., & Llorent-Bedmar, V. (2020). Women’s Well-Being and Rural Development in Depopulated Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(6), 1966. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17061966