Employing Participatory Citizen Science Methods to Promote Age-Friendly Environments Worldwide

Abstract

1. Introduction

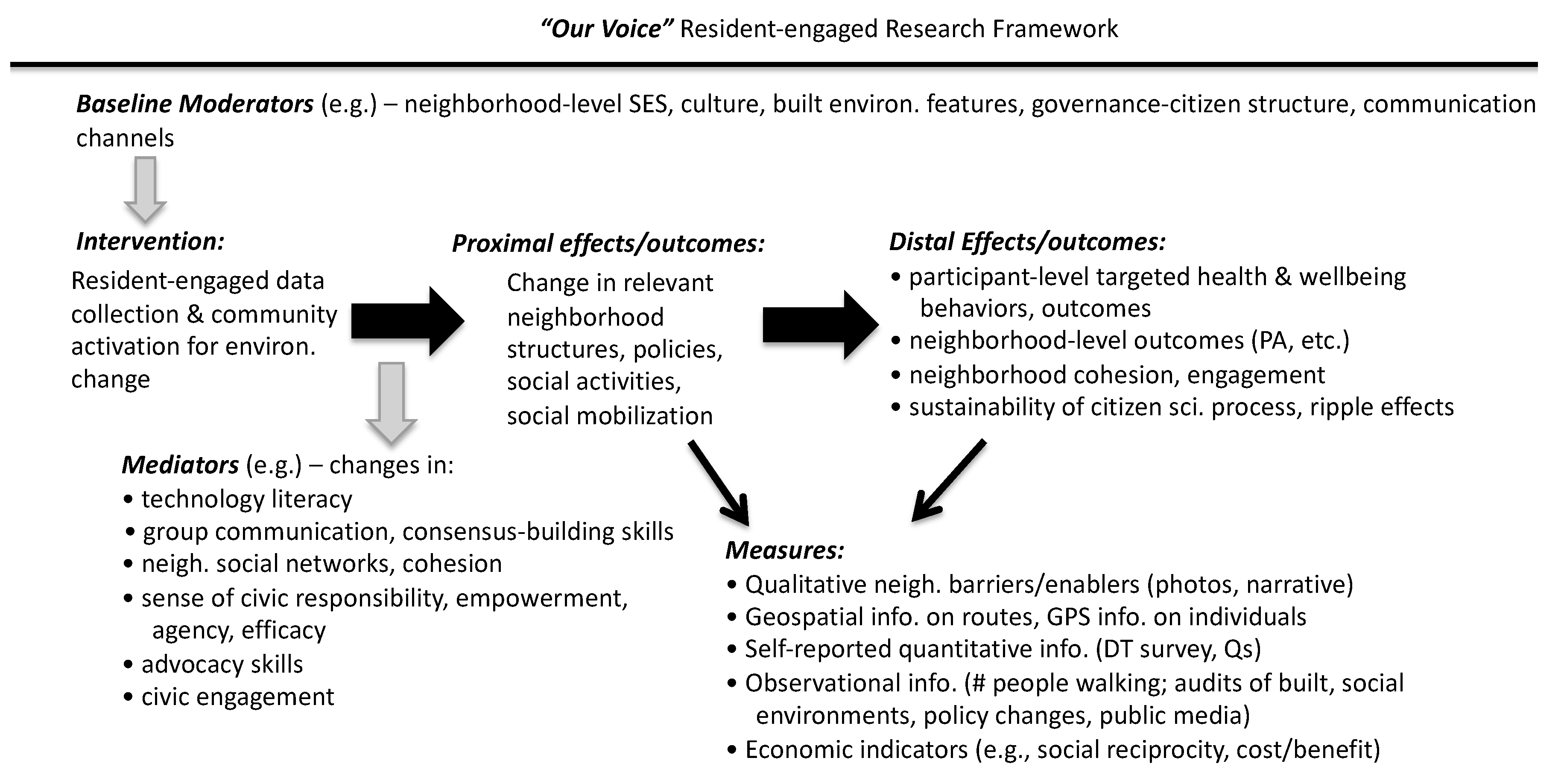

2. General Methods and Materials for the Our Voice Citizen Science Engagement Model

2.1. Overview

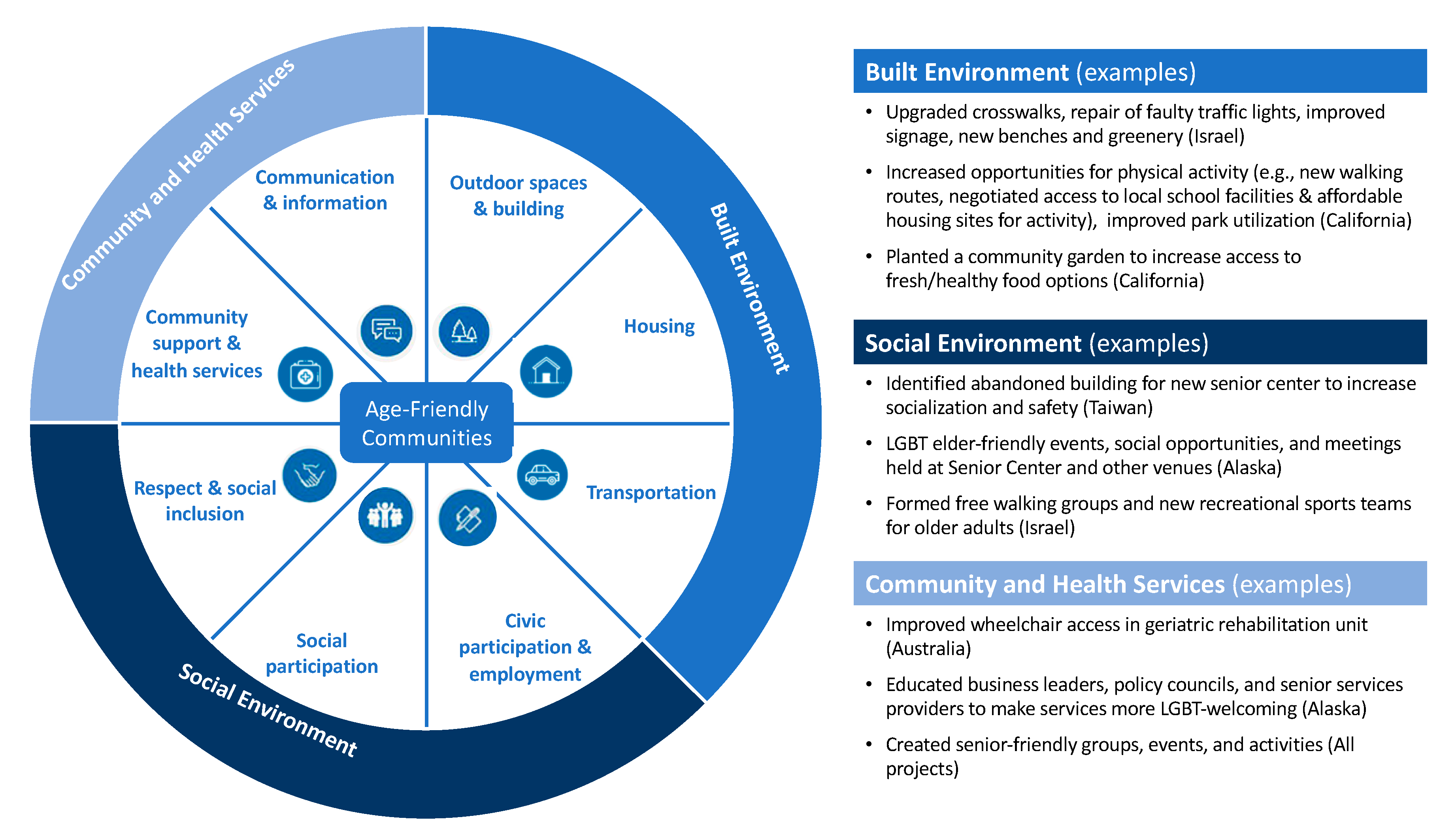

2.2. Characterizing Our Voice Project Initiatives Aimed at Built, Social and Community Service Environments

3. Results

3.1. Enhancing Built Environments to Promote Active Aging

3.1.1. Improving Neighborhood Walkability for Israeli Older Adults

3.1.2. Creating Convenient Multi-Generational Physical Activity and Recreation Opportunities in San Jose, CA

3.1.3. Other Projects Aimed at Enhancing Built Environments to Promote Age-Friendly Communities

3.2. Enhancing Social Environments to Promote Social Participation, Safety, Respect, and Inclusion

3.2.1. Creating Safe, Senior-Friendly Social Spaces in Cijin, Taiwan

3.2.2. Promoting Community-Wide Respect and Inclusion for LGBT Elders in Anchorage, Alaska

3.3. Increasing Access to an Age-Friendly Community and Health Services

3.3.1. Optimizing Comfort and Mobility in a Geriatric Medical Rehabilitation Setting

3.3.2. Enhancing Communication and Information to Connect Older Adults to Community and Health Services

3.4. User Experiences with the Discovery Tool App and Overall Our Voice Process

3.5. Maintaining Project Momentum to Achieve Successes and Address Challenges

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

- Continue to expand the scientific rigor, methods, and designs commensurate with this type of community-enabled research. This includes quasi-experimental pre–post comparison group designs [49], as well as, when appropriate and feasible, experimental designs comparing the efficacy of health interventions with and without the addition of “by the people” citizen science methods.

- Measurement batteries also should be expanded to more thoroughly capture change at different levels of impact, including at the individual, interpersonal, environmental and policy levels [44]. In addition, greater cross-project harmonization of the measurement batteries being employed in each study would accelerate cross-project learnings [44].

- Employ formal applications of qualitative comparative analysis to identify sets of conditions that are necessary and sufficient for successful implementation of the Our Voice model. Among the potential factors that may have favorable or detrimental effects on successful implementation are the following [43]: citizen scientists’ perceptions of whether the changes made adequately address the problems they identified; whether the problems and solutions align or conflict with priorities of other local groups, including neighborhood groups, local governments, etc.; the extent to which identified decision makers and stakeholders have the authority, interest, and resources to accomplish the proposed changes; whether or not there are committed champions dedicated to supporting, promoting, and driving the changes; and the best methods for promoting sustained resident involvement to enhance the chances of ripple effects, that is, the spread of community-engaged citizen science activities to other issues.

- Test innovative approaches for capturing, over time, all of the varied impacts of such resident-engaged approaches—both intended and unexpected—through using systematic methods such as ripple effects mapping (REM) [74]. REM is a participatory qualitative methodology where participants and stakeholders visually map together the “snowballing” trajectory of project-related activities and outcomes that accrue over time [74,75]. To thoroughly capture such effects, which can occur beyond the formal end of a project, lengthening the duration of project assessment activities is recommended.

- Prospectively combine use of the WHO age-friendly checklist and Our Voice methods to evaluate age-friendly features and identify feasible barriers and solutions across all eight topic areas.

- Expand the data capture capabilities of this platform through adding mobile sensors and other assessment tools to the Discovery Tool walks that are occurring around residents’ communities. In this manner, a more comprehensive picture of the potential health and quality of life impacts of specific community locales and features can emerge. An example of this is having residents use a wrist-worn sensor that collects electro-dermal and heart rate activity in helping to identify locations along a particular walking route that engender increases in arousal or stress [52].

- Explore linkages to other data platforms through introducing this type of complementary resident-centric, micro-environmental perspective to computational, epidemiological, and other “big data” scientists, given that these data are typically missing in “big data” sets. Such resident-collected data may be particularly relevant for vulnerable populations, including older adults [76].

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luepker, R.V. Increasing longevity: Causes, consequences, and prospects. In Longer Life and Healthy Aging, International Studies in Population; Yi, Z., Crimmins, E.M., Carrière, Y., Robine, J.M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 2, pp. 91–106. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy and Action Plan on Ageing and Health (2016–2020); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Beard, J.R.; Officer, A.; De Carvalho, I.A.; Sadana, R.; Pot, A.M.; Michel, J.P.; Lloyd-Sherlock, P.; Epping-Jordan, J.E.; Peeters, G.G.; Mahanani, W.R.; et al. The World report on ageing and health: A policy framework for healthy ageing. Lancet 2016, 387, 2145–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, R.J.; Angel, J.L.; Hill, T.D. Longer lives, sicker lives? Increased longevity and extended disability among Mexican-origin elders. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2015, 70, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, S.V.; Kubzansky, L.; Berkman, L.; Fay, M.; Kawachi, I. Neighborhood effects on the self-rated health of elders: Uncovering the relative importance of structural and service-related neighborhood environments. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2006, 61, S153–S160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruchno, R.A.; Wilson-Genderson, M.; Cartwright, F.P. The texture of neighborhoods and disability among older adults. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2012, 67, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibney, S.; Zhang, M.; Brennan, C. Age-friendly environments and psychosocial wellbeing: A study of older urban residents in Ireland. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffel, T.; Phillipson, C.; Scharf, T. Ageing in urban environments: Developing “age-friendly” cities. Crit. Soc. Policy 2012, 32, 597–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, C.D.; Camp, E.D.; Flux, D.; McClelland, R.W.; Sieppert, J. Community development with older adults in their neighborhoods: The elder friendly communities program. Fam. Soc. 2005, 86, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novek, S.; Menec, V.H. Older adults’ perceptions of age-friendly communities in Canada: A photovoice study. Ageing Soc. 2014, 34, 1052–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, C.W.; Everingham, J.A.; Warburton, J.; Cuthill, M.; Bartlett, H. What makes a community age-friendly: A review of international literature. Australas. J. Ageing 2009, 28, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menec, V.H.; Means, R.; Keating, N.; Parkhurst, G.; Eales, J. Conceptualizing age-friendly communities. Can. J. Aging 2011, 30, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, A.M.; Benjamin-Thomas, T.E.; McGrath, C.; Hand, C.; Laliberte Rudman, D. Participatory Action Research With Older Adults: A Critical Interpretive Synthesis. Gerontologist 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buffel, T.; Phillipson, C. A Manifesto for the Age-Friendly Movement: Developing a New Urban Agenda. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2018, 30, 173–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- English, P.B.; Richardson, M.J.; Garzon-Galvis, C. From Crowdsourcing to Extreme Citizen Science: Participatory Research for Environmental Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2018, 39, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottwald, S.; Laatikainen, T.E.; Kyttä, M. Exploring the usability of PPGIS among older adults: Challenges and opportunities. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2016, 30, 2321–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, P. Towards participatory geographic information systems for community-based environmental decision making. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1966–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, G.; Kyttä, M. Key issues and research priorities for public participation GIS (PPGIS): A synthesis based on empirical research. Appl. Geogr. 2014, 46, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolkafli, A.; Liu, Y.; Brown, G. Bridging the knowledge divide between public and experts using PGIS for land use planning in Malaysia. Appl. Geogr. 2017, 83, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahila-Tani, M.; Kytta, M.; Geertman, S. Does mapping improve public participation? Exploring the pros and cons of using public participation GIS in urban planning practices. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 186, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, C.D.; Oke, C.; Hehir, A.; Gordon, A.; Wang, Y.; Bekessy, S.A. Capturing residents’ values for urban green space: Mapping, analysis and guidance for practice. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 161, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.C.; Winter, S.J.; Chrisinger, B.W.; Hua, J.; Banchoff, A.W. Maximizing the promise of citizen science to advance health and prevent disease. Prev. Med. 2019, 119, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S.J.; Rosas, L.G.; Romero, P.P.; Sheats, J.L.; Buman, M.P.; Baker, C.; King, A.C. Using citizen scientists to gather, analyze, and disseminate information about neighborhood features that affect active living. J. Immigr. Minority Health 2015, 18, 1126–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, A.C.; Winter, S.J.; Sheats, J.L.; Rosas, L.G.; Buman, M.P.; Salvo, D.; Rodriguez, N.M.; Seguin, R.A.; Moran, M.; Garber, R.; et al. Leveraging citizen science and information technology for population physical activity promotion. Transl. J. ACSM 2016, 1, 30–44. [Google Scholar]

- Sheats, J.L.; Winter, S.J.; Romero, P.P.; King, A.C. FEAST: Empowering community residents to use technology to assess and advocate for healthy food environments. J. Urban Health 2017, 94, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garon, S.; Paris, M.; Beaulieu, M.; Veil, A.; Laliberte, A. Collaborative partnership in age-friendly cities: Two case studies from Quebec, Canada. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2014, 26, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffel, T.; McGarry, P.; Phillipson, C.; De Donder, L.; Dury, S.; De Witte, N.; Smetcoren, A.S.; Verté, D. Developing age-friendly cities: Case studies from Brussels and Manchester and implications for policy and practice. In Environmental Gerontology in Europe and Latin America: Policies and Perspectives on Environment and Aging; Sánchez-González, D., Rodríguez-Rodríguez, V., Eds.; Springer: Basel, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 15. [Google Scholar]

- Buffel, T.; Skyrme, J.; Phillipson, C. Connecting research with social responsibility: Developing age-friendly communities in Manchester, UK. In University Social Responsibility and Quality of Life: Concepts and Experiences in the Global World; Shek, D., Hollister, R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rowbotham, S.; McKinnon, M.; Leach, J.; Lamberts, R.; Hawe, P. Does citizen science have the capacity to transform population health science? Crit. Public Health 2017, 29, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, Health and Medicine Division, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, Committee on Community-Based Solutions to Promote Health Equity in the United States. Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kelty, C.; Panofsky, A. Disentangling public participation in science and biomedicine. Genome Med. 2014, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverton, J. A new dawn for citizen science. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009, 24, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Checklist of Essential Features of Age-Friendly Cities; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport, J. Studies in empowerment: Introduction to the issue. Prev. Hum. Serv. 1984, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Household Survey. People’s Perceptions of Their Neighborhood and Community Involvement: Results from the Social Capital Module of the General Household Survey 2000, 1st ed.; Office of National Statistics: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sallis, J.F.; Owen, N. Ecological models of health behavior. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice, 3rd ed.; Glanz, K., Rimer, B.K., Lewis, F.M., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 462–484. [Google Scholar]

- King, A.C. Theory’s role in shaping behavioral health research for population health. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Toward a psychology of human agency. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 1, 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothman, J. Approaches to community intervention. In Strategies of Community Intervention; Rothman, J., Tropman, J.E., Eds.; Peacock: Itasca, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Aron, D.C.; Keith, R.E.; Kirsh, S.R.; Alexander, J.A.; Lowery, J.C. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinckson, E.; Schneider, M.; Winter, S.J.; Stone, E.; Puhan, M.; Stathi, A.; Porter, M.M.; Gardiner, P.A.; Dos Santos, D.L.; Wolff, A.; et al. Citizen science applied to building healthier community environments: Advancing the field through shared construct and measurement development. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buman, M.P.; Winter, S.J.; Sheats, J.L.; Hekler, E.B.; Otten, J.J.; Grieco, L.A.; King, A.C. The Stanford Healthy Neighborhood Discovery Tool: A computerized tool to assess active living environments. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 44, e41–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buman, M.P.; Winter, S.J.; Baker, C.; Hekler, E.B.; Otten, J.J.; King, A.C. Neighborhood Eating and Activity Advocacy Teams (NEAAT): Engaging older adults in policy activities to improve food and physical environments. Transl. Behav. Med. 2012, 2, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguin, R.A.; Morgan, E.H.; Connor, L.M.; Garner, J.A.; King, A.C.; Sheats, J.L.; Winter, S.J.; Buman, M.P. Rural food and physical activity assessment using an electronic tablet-based application, New York, 2013–2014. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2015, 12, E102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas, L.G.; Salvo, D.; Winter, S.J.; Cortes, D.; Rivera, J.; Rodriguez, N.M.; King, A.C. Harnessing Technology and Citizen Science to Support Neighborhoods that Promote Active Living in Mexico. J. Urban Health 2016, 93, 953–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rodriguez, N.M.; Arce, A.; Kawaguchi, A.; Hua, J.; Broderick, B.; Winter, S.J.; King, A.C. Enhancing Safe Routes to School Programs through Community-Engaged Citizen Science: Two Pilot Investigations in Lower Density Areas of Santa Clara County, California, USA. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, M.; Werner, P.; Doron, I.; HaGani, N.; Benvenisti, Y.; King, A.C.; Winter, S.J.; Sheats, J.L.; Garber, R.; Motro, H.; et al. Detecting inequalities in healthy and age-friendly environments: Examining the Stanford Healthy Neighborhood Discovery Tool in Israel. In International Research Workshop on Inequalities in Health Promoting Environments: Physical Activity and Diet; University of Haifa: Haifa, Israel, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chrisinger, B.W.; Ramos, A.; Shaykis, F.; Martinez, T.; Banchoff, A.W.; Winter, S.J.; King, A.C. Leveraging citizen science for healthier food environments: A pilot study to evaluate corner stores in Camden, New Jersey. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrisinger, B.; King, A.C. Stress experiences in neighborhood and social environments (SENSE): A pilot study to integrate the quantified self with citizen science to improve the built environment and health. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2018, 17, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuckett, A.G.; Freeman, A.; Hetherington, S.; Gardiner, P.A.; King, A.C.; on behalf of Burnie Brae Citizen Scientists. Older adults using Our Voice Citizen Science to create change in their neighborhood environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, M.R.; Werner, P.; Doron, I.; HaGani, N.; Benvenisti, Y.; King, A.C.; Winter, S.J.; Sheats, J.L.; Garber, R.; Motro, H.; et al. Exploring the objective and perceived environmental attributes of older adults’ neighborhood walking routes: A mixed methods analysis. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2016, 25, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, M.; Van Cauwenberg, J.; Hercky-Linnewiel, R.; Cerin, E.; Deforche, B.; Plaut, P. Understanding the relationships between the physical environment and physical activity in older adults: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plough, A.L. Measuring What Matters: Introducing a New Action Framework; Robert Wood Johnson Foundation: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- King, A.C.; Sallis, J.F.; Frank, L.D.; Saelens, B.E.; Cain, K.; Conway, T.L.; Chapman, J.E.; Ahn, D.K.; Kerr, J. Aging in neighborhoods differing in walkability and income: Associations with physical activity and obesity in older adults. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 73, 1525–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report; Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Moran, M.; Werner, P.; Doron, L.; Benvenisti, Y.; HaGani, N.; King, A.C.; Winter, S.J.; Sheats, J. Health Promoting Environments: Participatory Action Research for Health and Age-Friendly Neighbourhoods (Research Report); JDC Israel Eshel: Jerusalem, Israel, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, T.L.; Cohen, D.A. SOPARC (System for Observing Play and Recreation in Communities)—Description and Procedures Manual; San Diego State University: San Diego, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, S.J.; Buman, M.P.; Sheats, J.L.; Hekler, E.B.; Otten, J.J.; Baker, C.; Cohen, D.; Butler, B.A.; King, A.C. Harnessing the potential of older adults to measure and modify their environments: Long-term successes of the Neighborhood Eating and Activity Advocacy Team (NEAAT) Study. Transl. Behav. Med. 2014, 4, 226–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemperman, A.; van den Berg, P.; Weijs-Perrée, M.; Uijtdewillegen, K. Loneliness of older adults: Social network and the living environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 2005, 365, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.Y.; Huang, C.S. Aging in Taiwan: Building a Society for Active Aging and Aging in Place. Gerontologist 2016, 56, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, Y.; Hua, J.; Banchoff, A.W.; Winter, S.J.; Liou, D.; King, A.C. Harnessing technology and citizen science to support age-friendly neighborhoods in Taiwan. Ann. Behav. Med. 2018, 52, S818. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales, G.; Henning-Smith, C. Health Disparities by Sexual Orientation: Results and Implications from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. J. Community Health 2017, 42, 1163–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, D.K.; Holdorf, M.; Sudbeck, D.; Schmidt, J.P. Safe and Healthy Aging for LGBT Elders Using Citizen Science: Discoveries from “Our Voice SAGE Alaska”; Alaska Public Health Summit: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, R.J.; Raudenbush, S.W.; Earls, F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 1997, 277, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jong Gierveld, J.; Van Tilburg, T. A 6-item scale for overall, emotional, and social loneliness: Confirmatory tests on survey data. Res. Aging 2006, 28, 582–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chu, Y.; Salmon, M.A. Predicting Perceived Isolation among Midlife and Older LGBT Adults: The Role of Welcoming Aging Service Providers. Gerontologist 2018, 58, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks-Cleator, L.A.; Giles, A.R.; Flaherty, M. Community-level factors that contribute to First Nations and Inuit older adults feeling supported to age well in a Canadian city. J. Aging Stud. 2019, 48, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, E.A.; Oberlink, M.; Scharlach, A.E.; Neal, M.B.; Stafford, P.B. Age-friendly community initiatives: Conceptual issues and key questions. Gerontologist 2015, 55, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonyea, J.G.; Hudson, R.B. Emerging models of age-friendly communities: A. framework for understanding inclusion. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2015, 25, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washburn, L.T.; Traywick, L.; Thornton, L.; Vincent, J.; Brown, T. Using Ripple Effects Mapping to evaluate a community-based health program: Perspectives of program implementers. Health Promot. Pract. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welborn, R.; Downey, L.; Dyk, P.H.; Monroe, P.A.; Tayler-Mackey, C.; Worthy, S.L. Turning the tide on poverty: Documenting impacts through ripple effect mapping. Community Dev. 2016, 47, 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satariano, W.A. The Epidemiology of Aging: An Ecological Approach; Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Inc.: Sudbury, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

| Location and Project Focus | Description and Participants (N = Sample Size) | Community Features Identified | Strategies Proposed and Changes Enacted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | |||

| BUILT ENVIRONMENT | ||||

| Haifa, Israel1 Age- and activity-friendly cities [1] | Ethnically and socioeconomically diverse adults ages 50 years and older (N = 59) from 4 neighborhoods in Haifa |

|

|

|

| East Palo Alto, CA (USA) Senior-friendly activity and food environments [16,27] | Assessment and advocacy around food and physical activity environments of local neighborhoods (N = 12 ethnically diverse low-income older adults living in senior public housing) |

|

|

|

| San Mateo County, CA (USA) Food access and transportation [18] | Examination of the factors that facilitate or hinder access to food, and food-related behavior, followed by advocacy for positive environmental and policy-level changes. (N = 23 ethnically diverse, food insecure, low-income older adults) |

|

|

|

| North Fair Oaks, CA (USA) Neighborhood walkability and security across generations [25] | Assessment of neighborhood built-environment features that help or hinder physical activity (N = 10 low-income Latinx adults, mean age 71 years and 10 low-income Latinx adolescents, mean age 13 years) |

|

|

|

| Cuernavaca, Mexico Supporting intergenerational active living across socioeconomic strata [19] | Testing the acceptability and feasibility of using the Our Voice approach to assess walkability environments in four neighborhoods in Mexico, stratified according to socioeconomic status and walkability. (N = 32 adults, 9 adolescents) |

|

|

|

| Curitiba, Brazil Neighborhood environmental characteristics and physical activity among older adults | Older adults from neighborhood areas with high and low walkability and SES (N = 32) |

|

|

|

| Santa Clara and San Mateo Counties, CA, (USA) Improving walkability around affordable senior housing sites |

Older adult residents and neighbors of affordable housing sites, enrolled in a physical activity intervention (N = 69) |

|

|

|

| Manitoba, Canada Creating an age-friendly campus | Older people (≥65 years) assessed overall age-friendliness of the University of Manitoba’s Fort Garry campus (N = 10) |

|

|

|

| Bath, Kent, Keynsham, Wolverhampton, UK Increasing age- and activity-friendliness of diverse communities | Increasing the age and activity friendliness of geographically and socioeconomically diverse communities (N = 19 older adults, 66 ± 7 years old) |

|

|

|

| Temuco, Chile Neighborhood environmental characteristics that promote quality of life and physical activity among older adults | Community-dwelling older adults from neighborhoods with different socioeconomic status and walkability (N = 60, ≥60 years) |

|

|

|

| East San Jose, CA (USA) Intergenerational approaches to building a healthy community | Collaboration with SOMOS Mayfair organization, and local Public Health Department; (N = 50 multi-aged residents |

|

|

|

| SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT | ||||

| Anchorage, Alaska1 Safe and healthy aging for older LGBT residents | Analysis of environmental factors that impact feelings of social isolation (N = 8) |

|

|

|

| Cijin, Taiwan1 Senior-friendly places for social and recreational activities | Older adults with mean age 70 years (SD = 10), 33% women, all with a high school education (N = 15) |

|

|

|

| COMMUNITY AND HEALTH SERVICES | ||||

| Brisbane, Australia1 Ensuring a mobility-friendly geriatric medical rehabilitation unit | Older adults in a medical rehabilitation unit (N = 10; 8 confined to wheelchairs) |

|

|

|

| City | Neighborhood | City Description | Local Partnering Organizations | Citizen Scientist Population (N = Sample Size) | Partnership and Recruitment Process | Our Voice Facilitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lod | Sharett |

|

| N = 30

|

|

|

| Ganei Aviv | N = 15

| |||||

| Tel Aviv | Shapira |

|

| N = 25

|

|

|

| Mo’adon Mitchell |

|

| N = 9

|

|

| |

| Hatikva |

|

| N = 14

|

|

| |

| Ajami |

|

| N = 35

|

|

| |

| Bat Yam | Gordon |

|

| N = 10

|

|

|

| Negba |

| N = 10

|

| |||

| Petah Tikvah | Menachem Ratzon |

|

| N = 12

|

|

|

| Sela | N = 8

| |||||

| Beit Dani | N = 8

| |||||

| Smilansky | N = 8

| |||||

| Jerusalem | Beit Hakerem |

|

| N = 38

|

|

|

| Har Homa |

|

|

|

|

|

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

King, A.C.; King, D.K.; Banchoff, A.; Solomonov, S.; Ben Natan, O.; Hua, J.; Gardiner, P.; Goldman Rosas, L.; Rodriguez Espinosa, P.; Winter, S.J.; et al. Employing Participatory Citizen Science Methods to Promote Age-Friendly Environments Worldwide. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051541

King AC, King DK, Banchoff A, Solomonov S, Ben Natan O, Hua J, Gardiner P, Goldman Rosas L, Rodriguez Espinosa P, Winter SJ, et al. Employing Participatory Citizen Science Methods to Promote Age-Friendly Environments Worldwide. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(5):1541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051541

Chicago/Turabian StyleKing, Abby C., Diane K. King, Ann Banchoff, Smadar Solomonov, Ofir Ben Natan, Jenna Hua, Paul Gardiner, Lisa Goldman Rosas, Patricia Rodriguez Espinosa, Sandra J. Winter, and et al. 2020. "Employing Participatory Citizen Science Methods to Promote Age-Friendly Environments Worldwide" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 5: 1541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051541

APA StyleKing, A. C., King, D. K., Banchoff, A., Solomonov, S., Ben Natan, O., Hua, J., Gardiner, P., Goldman Rosas, L., Rodriguez Espinosa, P., Winter, S. J., Sheats, J., Salvo, D., Aguilar-Farias, N., Stathi, A., Akira Hino, A., Porter, M. M., & On behalf of the Our Voice Global Citizen Science Research Network. (2020). Employing Participatory Citizen Science Methods to Promote Age-Friendly Environments Worldwide. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), 1541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051541