Internet Gaming Disorder Clustering Based on Personality Traits in Adolescents, and Its Relation with Comorbid Psychological Symptoms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Millon Adolescent Personality Inventory (MACI)

2.2.2. Symptom CheckList-90 Items-Revised (SCL-90-R)

2.2.3. State-Trait Anxiety Index (STAI)

2.2.4. DSM-5 IGD Criteria

2.2.5. Sociodemographical Variables

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

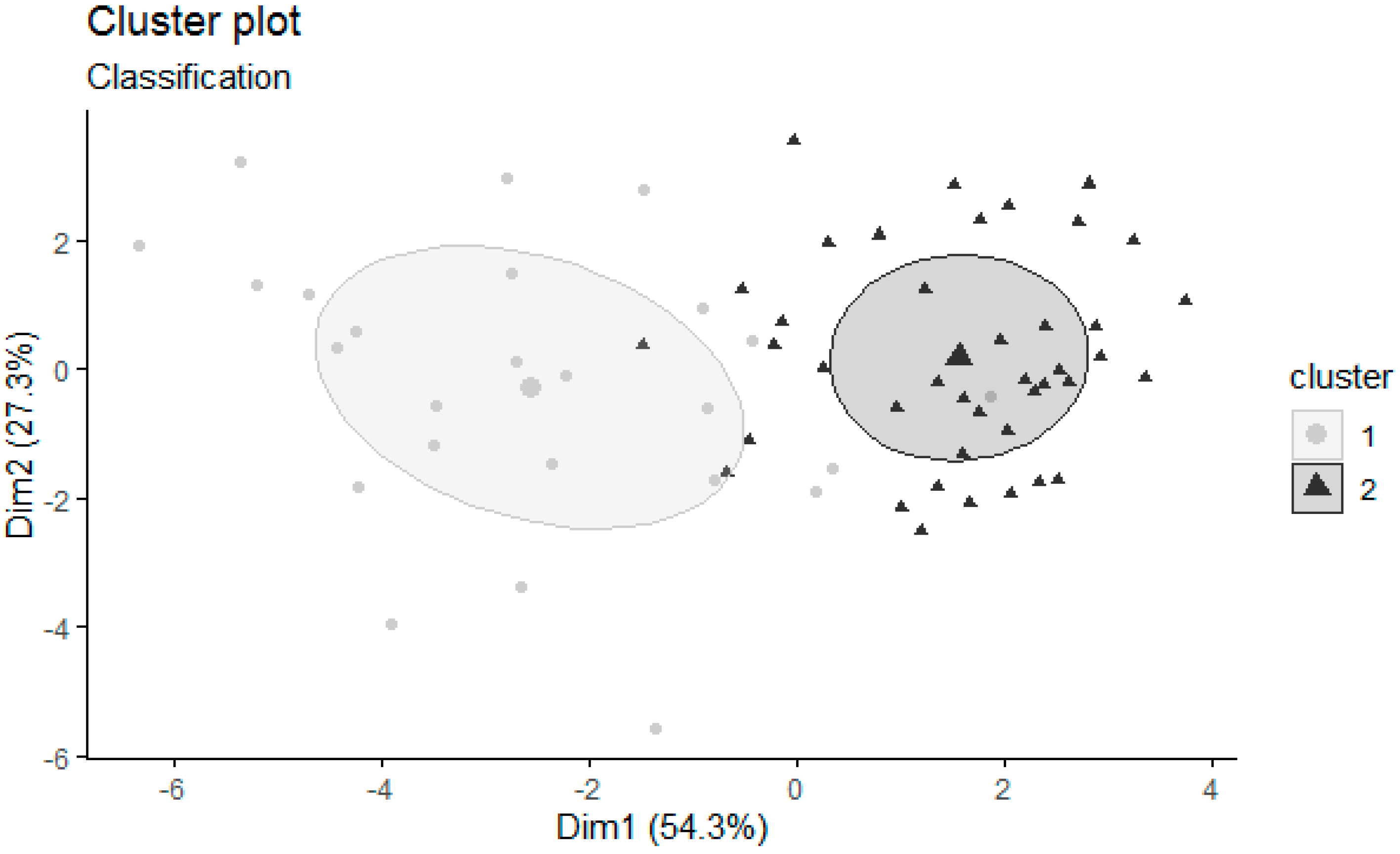

3.1. Cluster Composition: Description for the Cluster Indicators

3.2. Comparison between the Clusters in Sociodemographic and Clinical Variables

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics 11th Revision; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Poli, R. Internet addiction update: Diagnostic criteria, assessment and prevalence. Neuropsychiatry 2017, 07, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauth-Bühler, M.; Mann, K. Neurobiological correlates of internet gaming disorder: Similarities to pathological gambling. Addict. Behav. 2017, 64, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaptsis, D.; King, D.; Delfabbro, P.; Gradisar, M. Withdrawal symptoms in internet gaming disorder: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 43, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; (DSM-5); American Psychiatric Association, Ed.; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gervasi, A.M.; La Marca, L.; Costanzo, A.; Pace, U.; Guglielmucci, F.; Schimmenti, A. Personality and Internet Gaming Disorder: A Systematic Review of Recent Literature. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2017, 4, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şalvarlı, Ş.İ.; Griffiths, M.D. Internet Gaming Disorder and Its Associated Personality Traits: A Systematic Review Using PRISMA Guidelines. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, G.; Deary, I.J.; Whiteman, M.C. Personality Traits, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; ISBN 9780511812743. [Google Scholar]

- Agüera, Z.; Krug, I.; Sánchez, I.; Granero, R.; Penelo, E.; Peñas-Lledó, E.; Jiménez-Murcia, S.; Menchón, J.M.; Fernández-Aranda, F. Personality Changes in Bulimia Nervosa after a Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2012, 20, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.J.; Namkoong, K.; Ku, T.; Kim, S.J. The relationship between online game addiction and aggression, self-control and narcissistic personality traits. Eur. Psychiatry 2008, 23, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. The moderating role of psychosocial well-being on the relationship between escapism and excessive online gaming. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 38, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehroof, M.; Griffiths, M.D. Online gaming addiction: The role of sensation seeking, self-control, neuroticism, aggression, state anxiety, and trait anxiety. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2010, 13, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaal, Y.; Chatton, A.; Rothen, S.; Achab, S.; Thorens, G.; Zullino, D.; Gmel, G. Psychometric properties of the 7-item game addiction scale among french and German speaking adults. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Murcia, S.; Fernández-Aranda, F.; Granero, R.; Chóliz, M.; La Verde, M.; Aguglia, E.; Signorelli, M.S.; Sá, G.M.; Aymamí, N.; Gómez-Peña, M.; et al. Video game addiction in gambling disorder: Clinical, psychopathological, and personality correlates. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 7, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, K.W.; Beutel, M.E.; Egloff, B.; Wölfling, K. Investigating risk factors for Internet gaming disorder: A comparison of patients with addictive gaming, pathological gamblers and healthy controls regarding the big five personality traits. Eur. Addict. Res. 2014, 20, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festl, R.; Scharkow, M.; Quandt, T. Problematic computer game use among adolescents, younger and older adults. Addiction 2013, 108, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.W.; Ho, R.T.H.; Chan, C.L.W.; Tse, S. Exploring personality characteristics of Chinese adolescents with internet-related addictive behaviors: Trait differences for gaming addiction and social networking addiction. Addict. Behav. 2015, 42, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montag, C.; Flierl, M.; Markett, S.; Walter, N.; Jurkiewicz, M.; Reuter, M. Internet addiction and personality in first-person-shooter video gamers. J. Media Psychol. 2011, 23, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goby, V.P. Personality and Online/Offline Choices: MBTI Profiles and Favored Communication Modes in a Singapore Study. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2006, 9, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.K.; Jain, A.K.; Murty, M.N.; Flynn, P.J. Data Clustering: A Review. ACM Comput. Surv. 1999, 31, 264–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, H.R.; Helinski, S.; Spanagel, R. Cluster and meta-analyses on factors influencing stress-induced alcohol drinking and relapse in rodents. Addict. Biol. 2014, 19, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alikhanian, H.; Crawford, J.D.; DeSouza, J.F.X.; Cheyne, D.O.; Blohm, G. Adaptive cluster analysis approach for functional localization using magnetoencephalography. Front. Neurosci. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, D.; Dymnicki, A.B.; Mohatt, N.; Allen, J.; Kelly, J.G. Clustering Methods with Qualitative Data: A Mixed-Methods Approach for Prevention Research with Small Samples. Prev. Sci. 2015, 16, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamito, P.S.; Morais, D.G.; Oliveira, J.G.; Brito, R.; Rosa, P.J.; Gaspar De Matos, M. Frequency is not enough: Patterns of use associated with risk of Internet addiction in Portuguese adolescents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 58, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Moya, E.M.; Jiménez-Murcia, S.; Aymamí, M.N.; Gómez-Peña, M.; Granero, R.; Santamaría, J.; Menchón, J.M.; Fernández-Aranda, F. Subtyping study of a pathological gamblers sample. Can. J. Psychiatry 2010, 55, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Fuente-Tomas, L.; Arranz, B.; Safont, G.; Sierra, P.; Sanchez-Autet, M.; Garcia-Blanco, A.; Garcia-Portilla, M.P. Classification of patients with bipolar disorder using k-means clustering. PLoS ONE 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vachon, D.D.; Bagby, R.M. Pathological Gambling Subtypes. Psychol. Assess. 2009, 21, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suomi, A.; Dowling, N.A.; Jackson, A.C. Problem gambling subtypes based on psychological distress, alcohol abuse and impulsivity. Addict. Behav. 2014, 39, 1741–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granero, R.; Fernandez-Aranda, F.; Mestre-Bach, G.; Steward, T.; Bano, M.; Agvera, Z.; Mallorqui-Bague, N.; Aymami, N.; Gomez-Pena, M.; Sancho, M.; et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for compulsive buying behavior: Predictors of treatment outcome. Eur. Psychiatry 2017, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billieux, J.; Thorens, G.; Khazaal, Y.; Zullino, D.; Achab, S.; Van der Linden, M. Problematic involvement in online games: A cluster analytic approach. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 43, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Rodríguez, A.; Griffiths, M.D.; Carbonell, X.; Oberst, U. Internet gaming disorder in adolescence: Psychological characteristics of a clinical sample. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallorquí-Bagué, N.; Fernández-Aranda, F.; Lozano-Madrid, M.; Granero, R.; Mestre-Bach, G.; Baño, M.; Pino-Gutiérrez, A.D.; Gómez-Peña, M.; Aymamí, N.; Menchón, J.M.; et al. Internet gaming disorder and online gambling disorder: Clinical and personality correlates. J. Behav. Addict. 2017, 6, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Bueso, V.; Santamaría, J.; Fernández, D.; Merino, L.; Montero, E.; Ribas, J. Association between Internet Gaming Disorder or Pathological Video-Game Use and Comorbid Psychopathology: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018, 15, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millon, T. Manual of Millon Adolescent Clinical Inventory; National Computer Systems: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre, G. Adaptación Español del MACI; TEA: Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Murrie, D.C.; Cornell, D.G. Psychopathy screening of incarcerated juveniles: A comparison of measures. Psychol. Assess. 2002, 14, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Salekin, R.T.; Larrea, M.A.; Ziegler, T. Relationships between the MACI and the BASC in the assessment of child and adolescent offenders. J. Forensic Psychol. Pract. 2002, 2, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velting, D.M.; Rathus, J.H.; Miller, A.L. MACI personality scale profiles of depressed adolescent suicide attempters: A pilot study. J. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 56, 1381–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, D.L.; Duty, K.J.; Leibowitz, G.S. Differences between sexually victimized and nonsexually victimized male adolescent sexual abusers: Developmental antecedents and behavioral comparisons. J. Child Sex. Abus. 2011, 20, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, L.; Kirchner, T. Suicidal tendency among adolescents with adjustment disorder: Risk and protective personality factors. Crisis 2015, 36, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grilo, C.M.; Fehon, D.C.; Walker, M.; Martino, S. A comparison of adolescent inpatients with and without wubstance abuse using the Millon Adolescent Clinical Inventory. J. Youth Adolesc. 1996, 25, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derogatis, L.R. SCL-90-R. Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual; Clinical Psychometric: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis, L.R. SCL-90-R. Cuestionario de 90 Síntomas-Manual. [Questionnaire of the 90 Symptoms-Manual]; TEA Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.; Gorsuch, R.L.; Lushene, R.E. Manual for the State/Trait Anxiety Inventory; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Guillén-Riquelme, A.; Buela-Casal, G. Psychometric revision and differential item functioning in the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Psicothema 2011, 23, 510–515. [Google Scholar]

- First, M.; Gibbon, M.; Spitzer, R.; Williams, J. Users Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM IV Axis I Disorders—Research Version (SCID-I, Version 2.0); New York State Psychiatric Institute: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Scrucca, L.; Raftery, A.E. Clustvarsel: A package implementing variable selection for Gaussian model-based clustering in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2018, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassambara, A.; Mundt, F. Factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses. R Package Version 2017, 1, 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Dempster, A.P.; Laird, N.M.; Rubin, D.B. Maximum Likelihood from Incomplete Data via the EM Algorithm. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 1977, 39, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan, G.J.; Krishnan, T. (Thriyambakam) The EM Algorithm and Extensions; Wiley-Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 9780471201700. [Google Scholar]

- Fraley, C.; Raftery, A.E. Model-based methods of classification: Using the mclust software in chemometrics. J. Stat. Softw. 2007, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mclachlan, G.J.; Lee, S.X.; Rathnayake, S.I. Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application Finite Mixture Models. Annu. Rev. Stat. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; L. Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988; ISBN 9780805802832. [Google Scholar]

- Lehenbauer-Baum, M.; Klaps, A.; Kovacovsky, Z.; Witzmann, K.; Zahlbruckner, R.; Stetina, B.U. Addiction and Engagement: An Explorative Study Toward Classification Criteria for Internet Gaming Disorder. Cyberpsychology. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2015, 18, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentile, D.A.; Choo, H.; Liau, A.; Sim, T.; Li, D.; Fung, D.; Khoo, A. Pathological video game use among youths: A two-year longitudinal study. Pediatrics 2011, 127, e319–e329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seay, A.F.; Kraut, R.E. Project Massive: Self-Regulation and Problematic Use of Online Gaming. In Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 24–28 April 2007; pp. 829–838. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, K.W.; Koch, A.; Dickenhorst, U.; Beutel, M.E.; Duven, E.; Wölfling, K. Addressing the Question of Disorder-Specific Risk Factors of Internet Addiction: A Comparison of Personality Traits in Patients with Addictive Behaviors and Comorbid Internet Addiction. Biomed Res. Int. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rooij, A.J.; Schoenmakers, T.M.; Vermulst, A.A.; Van Den Eijnden, R.J.J.M.; Van De Mheen, D. Online video game addiction: Identification of addicted adolescent gamers. Addiction 2011, 106, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, S.; Bogusz, E.; Green, D.A. Stuck on screens: Patterns of computer and gaming station use in youth seen in a psychiatric clinic. J. Can. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2011, 20, 86–94. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, S.H.; Hooley, J.M. Clinical and Personality Correlates of MMO Gaming. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2013, 31, 424–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starcevic, V.; Berle, D.; Porter, G.; Fenech, P. Problem Video Game Use and Dimensions of Psychopathology. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2011, 9, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetina, B.U.; Kothgassner, O.D.; Lehenbauer, M.; Kryspin-Exner, I. Beyond the fascination of online-games: Probing addictive behavior and depression in the world of online-gaming. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.L.; Delfabbro, P.H.; Zwaans, T.; Kaptsis, D. Clinical features and axis I comorbidity of Australian adolescent pathological Internet and video game users. Aust. N. Zeal. J. Psychiatry 2013, 47, 1058–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellanos-Ryan, N.; Briere, F.N.; O’Leary-Barrett, M.; Banaschewski, T.; Bokde, A.; Bromberg, U.; Biichel, C.; Flor, H.; Frouin, V.; Gallinat, J.; et al. The IMAGEN Consortium The structure of psychopathology in adolescence and its common personality and cognitive correlates. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2016, 125, 1039–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotov, R.; Gamez, W.; Schmidt, F.; Watson, D. Linking “Big” personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 136, 768–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tackett, J.L.; Kushner, S.C.; De Fruyt, F.; Mervielde, I. Delineating Personality Traits in Childhood and Adolescence: Associations Across Measures, Temperament, and Behavioral Problems. Assessment 2013, 20, 738–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malouff, J.M.; Thorsteinsson, E.B.; Schutte, N.S. The relationship between the five-factor model of personality and symptoms of clinical disorders: A meta-analysis. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2005, 27, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carragher, N.; Teesson, M.; Sunderland, M.; Newton, N.C.; Krueger, R.F.; Conrod, P.J.; Barrett, E.L.; Champion, K.E.; Nair, N.K.; Slade, T. The structure of adolescent psychopathology: A symptom-level analysis. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 981–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, J.T. The MACI: Composition and Clinical Applications. In The Millon Inventories: Clinical and Personality Assessment; Millon, T., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 363–388. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, C.T.; Frick, P.J.; Killian, A.L. The relation of narcissism and self-esteem to conduct problems in children: A preliminary investigation. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2003, 32, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A.K.; Weinstein, N.; Murayama, K. Internet gaming disorder: Investigating the clinical relevance of a new phenomenon. Am. J. Psychiatry 2017, 174, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothmund, T.; Klimmt, C.; Gollwitzer, M. Low Temporal Stability of Excessive Video Game Use in German Adolescents. J. Media Psychol. 2018, 30, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, C.J.; John, O.P.; Gosling, S.D.; Potter, J. Age Differences in Personality Traits From 10 to 65: Big Five Domains and Facets in a Large Cross-Sectional Sample. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 100, 330–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, A.M.; Nielsen, R.K.L.; van Rooij, A.J.; Ferguson, C.J. Video game addiction: The push to pathologize video games. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2017, 48, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Ramo, D.E.; Steven, R.C.; Bourgeois, J.A. Internet gaming disorder: Trends in prevalence 1998–2016. Addict. Behav. 2017, 75, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, D.H.; Kim, S.M.; Lee, Y.S.; Renshaw, P.F. The effect of family therapy on the changes in the severity of on-line game play and brain activity in adolescents with on-line game addiction. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2012, 202, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.M.; Han, D.H.; Lee, Y.S.; Renshaw, P.F. Combined cognitive behavioral therapy and bupropion for the treatment of problematic on-line game play in adolescents with major depressive disorder. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 1954–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Personality Traits | Mean | SD | Median | IQR | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Introversive | 25.20 | 11.61 | 23 | 17.80 | 9 | 52 |

| Inhibited | 20.86 | 10.82 | 18.50 | 25.50 | 4 | 48 |

| Doleful | 11.47 | 9.92 | 8 | 14 | 0 | 41 |

| Submissive | 43.85 | 10.00 | 45.50 | 13 | 21 | 69 |

| Histrionic | 36.55 | 9.97 | 37 | 14.30 | 12 | 54 |

| Egotistic | 33.47 | 10.85 | 35 | 15 | 3 | 51 |

| Unruly | 30.23 | 9.39 | 29.50 | 11.80 | 10 | 52 |

| Forceful | 10.59 | 6.81 | 9 | 7.6 | 0 | 34 |

| Conforming | 45.41 | 9.05 | 46 | 13.30 | 18 | 62 |

| Oppositional | 20.30 | 9.86 | 20 | 12.80 | 4 | 44 |

| Self-Demeaning | 19.42 | 13.84 | 16 | 20 | 0 | 55 |

| Borderline Tendency | 11.70 | 7.72 | 11 | 12.50 | 0 | 30 |

| Independent Samples Test | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLUSTER 1 | CLUSTER 2 | |||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | t | df | Sig. (2 tailed) | Cohen’s d | |

| MACI | ||||||

| Submissive | 46.48 (11.86) | 42.24 (8.42) | 1.69 | 64 | 0.126 | 0.43 |

| Egotistic | 27.80 (3.03) | 36.93 (7.33) | −3.16 | 33.15 | 0.003 | −0.92 |

| Unruly | 34.12 (9.70) | 27.85 (8.45) | 2.76 | 64 | 0.010 | 0.70 |

| Conforming | 39.44 (8.19) | 49.04 (7.49) | −4.86 | 64 | 0.000 | −1.23 |

| Oppositional | 28.76 (8.58) | 15.14 (6.46) | 7.32 | 64 | 0.000 | 1.86 |

| STAI | ||||||

| Anxiety State | 18.72 (8.35) | 11.38 (7.52) | 3.67 | 63 | 0.000 | 0.94 |

| Anxiety Trait | 23.48 (8.11) | 12.64 (7.00) | 5.75 | 64 | 0.000 | 1.46 |

| Mann–Whitney U Test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLUSTER 1 | CLUSTER 2 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | U | Sig. (2 tailed) | Cohen’s d | |

| MACI | |||||

| Introversive | 35.76 (9.27) | 18.76 (7.44) | 948.50 | 0.000 | 2.08 |

| Inhibited | 29.88 (11.04) | 15.37 (5.94) | 883 | 0.000 | 1.76 |

| Doleful | 20.44 (9.42) | 6.00 (5.07) | 941 | 0.000 | 2.05 |

| Histrionic | 29.88 (10.95) | 40.61 (6.70) | 223.50 | 0.000 | −1.26 |

| Forceful | 14.56 (7.49) | 8.17 (5.07) | 781 | 0.000 | 1.05 |

| Self-Demeaning | 32.96 (11.51) | 11.17 (6.97) | 974 | 0.000 | 2.45 |

| Borderline Tend. | 19.44 (5.34) | 6.97 (4.39) | 998.5 | 0.000 | 2.61 |

| SCL-90-R | |||||

| Somatization | 0.55 (0.54) | 0.26 (0.27) | 718 | 0.006 | 0.75 |

| Obsessive-comp | 1.03 (0.60) | 0.61 (0.51) | 719 | 0.006 | 0.76 |

| Interp. sens. | 1.00 (0.81) | 0.38 (0.39) | 781 | 0.000 | 1.04 |

| Depression | 0.93 (0.72) | 0.28 (0.30) | 840.50 | 0.000 | 1.28 |

| Anxiety | 0.69 (0.81) | 0.21 (0.22) | 700 | 0.012 | 0.90 |

| Hostility | 1.10 (0.91) | 0.56 (0.45) | 708 | 0.009 | 0.81 |

| Phobia | 0.40 (0.57) | 0.10 (0.19) | 782.50 | 0.000 | 0.77 |

| Paranoid ideation | 1.03 (0.82) | 0.38 (0.43) | 773 | 0.000 | 1.06 |

| Psychoticism | 0.56 (0.50) | 0.14 (0.20) | 845 | 0.000 | 1.18 |

| Global severity | 0.80(0.56) | 0.33(0.25) | 833 | 0.000 | 1.20 |

| DSM 5 criteria | 5.84 (1.82) | 4.95 (1.55) | 684 | 0.019 | 0.54 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González-Bueso, V.; Santamaría, J.J.; Oliveras, I.; Fernández, D.; Montero, E.; Baño, M.; Jiménez-Murcia, S.; del Pino-Gutiérrez, A.; Ribas, J. Internet Gaming Disorder Clustering Based on Personality Traits in Adolescents, and Its Relation with Comorbid Psychological Symptoms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1516. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051516

González-Bueso V, Santamaría JJ, Oliveras I, Fernández D, Montero E, Baño M, Jiménez-Murcia S, del Pino-Gutiérrez A, Ribas J. Internet Gaming Disorder Clustering Based on Personality Traits in Adolescents, and Its Relation with Comorbid Psychological Symptoms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(5):1516. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051516

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Bueso, Vega, Juan José Santamaría, Ignasi Oliveras, Daniel Fernández, Elena Montero, Marta Baño, Susana Jiménez-Murcia, Amparo del Pino-Gutiérrez, and Joan Ribas. 2020. "Internet Gaming Disorder Clustering Based on Personality Traits in Adolescents, and Its Relation with Comorbid Psychological Symptoms" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 5: 1516. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051516

APA StyleGonzález-Bueso, V., Santamaría, J. J., Oliveras, I., Fernández, D., Montero, E., Baño, M., Jiménez-Murcia, S., del Pino-Gutiérrez, A., & Ribas, J. (2020). Internet Gaming Disorder Clustering Based on Personality Traits in Adolescents, and Its Relation with Comorbid Psychological Symptoms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), 1516. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051516