How Did Parents View the Impact of the Curriculum-Based HealthLit4Kids Program Beyond the Classroom?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context and Setting

2.2. Participants and Data Collection

2.3. Analytical Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Peerson, A.; Saunders, M. Health literacy revisited: What do we mean and why does it matter? Health Promot. Int. 2009, 24, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickbusch, I.; Wait, S.; Maag, D.; Banks, I. Navigating health: The role of health literacy. In Alliance for Health and the Future; International Longevity Centre: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- D’Eath, M.; Barry, M.M.; Sixsmith, J. A Rapid Evidence Review of Interventions for Improving Health Literacy: Insights into Health Communication; European Centre for Diseases Prevention and Control: Stockholm, Sweden, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sudore, R.L.; Schillinger, D. Interventions to Improve Care for Patients with Limited Health Literacy. J. Clin. Outcomes Manag. 2009, 16, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Visscher, B.B.; Steunenberg, B.; Heijmans, M.; Hofstede, J.M.; Deville, W.; van der Heide, I.; Rademakers, J. Evidence on the effectiveness of health literacy interventions in the EU: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bröder, J.; Okan, O.; Bauer, U.; Bruland, D.; Schlupp, S.; Bollweg, T.M.; Saboga-Nunes, L.; Bond, E.; Sørensen, K.; Bitzer, E.-M.; et al. Health literacy in childhood and youth: A systematic review of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; West, R.; Sheals, K.; Godinho, C.A. Evaluating the effectiveness of behaviour change techniques in health-related behaviour: A scoping review of methods used. Transl. Behav. Med. 2018, 8, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, C.G.; Bridgers, S.; Griffiths, T.; Gopnik, A. When children are better (or at least more open-minded) learners than adults: Developmental differences in learning the forms of causal relationships. Cognition 2014, 131, 284–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Currie, J.; Rossin-Slater, M. Early-life origins of life-cycle well-being: Research and policy implications. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2014, 34, 208–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. Young Children Develop in an Environment of Relationships: Working Paper 1. Available online: http://www.developingchild.net (accessed on 30 December 2019).

- Shonkoff, J.P.; Garner, A.S. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e232–e246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushing, C.C.; Brannon, E.E.; Suorsa, K.I.; Wilson, D.K. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Health Promotion Interventions for Children and Adolescents Using an Ecological Framework. J. Pediatric Psychol. 2014, 39, 949–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J.M.; Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory: A dialectical framework for understanding sociocultural influcences on student motivation. In Recent Developments in Neuroscience Research on Human Motivation; Kim, S., Reeve, J.M., Bong, M., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2004; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Schlechty, P.C. Leading for Learning: How to Transform Schools into Learning Organisations; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Valle, A.; Regueiro, B.; Nunez, J.C.; Rodriguez, S.; Pineiro, I.; Rosario, P. Academic Goals, Student Homework Engagement, and Academic Achievement in Elementary School. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Instrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, A.; Duncheon, N.; McDavid, L. Peers and Teachers as Sources of Relatedness Perceptions, Motivation, and Affective Responses in Physical Education. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2009, 80, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karagiannidis, Y.; Barkoukis, V.; Gourgourlis, V.; Kosta, G.; Antoniou, P. The role of motivation and metacognition on the development of cognitive and affective responses in physical education lessons: A self-determination approach. Motricidade 2015, 11, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.; Jungert, T.; Mageau, G.A.; Schattke, K.; Dedic, H.; Rosenfield, S.; Koestner, R. A self-determination theory approach to predicting school achievement over time: The unique role of intrinsic motivation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 39, 342–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Fahlman, M.M.; Martin, J. Effects of Teacher Autonomy Support and Students’ Autonomous Motivation on Learning in Physical Education. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2009, 80, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, T.; Yli-Piipari, S.; Barkoukis, V.; Liukkonen, J. Relationships among perceived motivational climate, motivational regulations, enjoyment, and PA participation among Finnish physical education students. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2017, 15, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cripps, K.; Zyromski, B. Adolescents’ Psychological Well-Being and Perceived Parental Involvement: Implications for Parental Involvement in Middle Schools. Res. Middle Level Educ. 2009, 33, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, A.T.; Mapp, K.L. A New Wave of Evidence: The Impact of School, Family, and Community Connections on Student Achievement; National Centre for Family & Community Connections with Schools: Austin, TX, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, L.; Fear, J.; Fox, S.; Sander, E. Parental Engagement in Learning and Schooling: Lessons from Research; Family-School and Community Partnerships Bureau: Canberra, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Begoray, D.L.; Wharf-Higgins, J.; MacDonald, M. High school health curriculum and health literacy: Canadian student voices. Glob. Health Promot. 2009, 16, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aira, T.; Välimaa, R.; Paakkari, L.; Villberg, J.; Kannas, L. Finnish pupils’ perceptions of health education as a school subject. Glob. Health Promot. 2014, 21, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government Department of Education, Skills and Employment. Parent Engagement in Children’s Learning. Available online: https://www.education.gov.au/parent-engagement-children-s-learning (accessed on 28 December 2019).

- Finn, R. Specifying the contributions of parents as pedagogues: Insights for parent-school partnerships. Aust. Educ. Res. 2019, 46, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redding, S.; Langdon, J.; Meyer, J.; Sheley, P. The Effects of Comprehensive Parent Engagement on Student Learning Outcomes; Harvard Family Research Project: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mutch, C.; Collins, S. Partners in Learning: Schools’ Engagement with Parents, Families, and Communities in New Zealand. Sch. Community J. 2012, 22, 167–188. [Google Scholar]

- Jago, R.; Rawlins, E.; Kipping, R.R.; Wells, S.; Chittleborough, C.; Peters, T.J.; Mytton, J.; Lawlor, D.A.; Campbell, R. Lessons learned from the AFLY5 RCT process evaluation: Implications for the design of physical activity and nutrition interventions in schools. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeWalt, D.A.; Hink, A. Health literacy and child health outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. Pediatrics 2009, 124, S265–S274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, D.; Maiden, K. Navigating the Health Care System: An Adolescent Health Literacy Unit for High Schools. J. Sch. Health 2018, 88, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driessnack, M.; Chung, S.; Perkhounkova, E.; Hein, M. Using the Newest Vital Sign to Assess Health Literacy in Children. J. Pediatric Health Care 2014, 28, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karmali, S.; Ng, V.; Battram, D.; Burke, S.; Morrow, D.; Pearson, E.S.; Tucker, P.; Mantler, T.; Cramp, A.; Petrella, R.; et al. Coaching and/or education intervention for parents with overweight/obsesity and their children: Study protocol of a single-centre randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesketh, K.R.; Lakshman, R.; van Sluijs, E.M.F. Barriers and facilitators to young children’s physical activity and sedentary behaviour: A systematic review and synthesis of qualitative literature. Pediatric Obes. 2017, 18, 987–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.L.; Griffin, T.L.; Lancashire, E.R.; Adab, P.; Parry, J.M.; Pallan, M.J. Parent and child perceptions of school-based obesity prevention in England: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.K.; Glick, A.; Yin, H.S. Health Literacy: Implications for Child Health. Pediatrics Rev. 2019, 40, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, M.A.; Alameda-Lawson, T. A Case Study of School-Linked, Collective Parent Engagement. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2012, 49, 651–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, R.; Patterson, K.; Flittner, A.; Elmer, S.; Osborne, R. School based Health Literacy Programs for Children (2-16 years): An international review. J. Sch. Health. in review.

- Franze, M.; Fendrich, K.; Schmidt, C.; Fahland, R.; Thyrian, J.; Plachta-Danielzik, S.; Seiberl, J.; Hoffmann, W.; Splieth, C. Implementation and evaluation of the population-based programme ‘health literacy in school-aged children’ (GeKoKids). J. Public Health 2011, 19, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Flecha, A.; Garcia, R.; Rudd, R. Using Health Literacy in School to Overcome Inequalities. Eur. J. Educ. 2011, 46, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Yang, T.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X. Study on Student Health Literacy Gained through Health Education in Elementary and Middle Schools in China. Health Educ. J. 2012, 71, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batterham, R.; Hawkins, M.; Collins, P.; Buchbinder, R.; Osborne, R. Health literacy: Applying current concepts to improve health services and reduce health inequalities. Public Health 2016, 132, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Reserach: A Practical Guide for Beginners; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Vasileiou, K.; Barnett, J.; Thorpe, S.; Young, T. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Hayfield, N.; Terry, G. Thematic analysis. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology; Willig, C., Rogers, W.S., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2017; pp. 844–859. [Google Scholar]

- Leger, L.S.; Nutbeam, D. A model for mapping linkages between health and education agencies to improve school health. J. Sch. Health 2000, 70, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, R.; Cruickshank, V.; Pill, S.; Elmer, S.; Murray, L.; Waddingham, S. HealthLit4Kids: Teacher reported dilemmas associated with student health literacy development in the primary school setting. Health Educ. Res. in review.

- Mabachi, N.M.; Cifuentes, M.; Barnard, J.; Brega, A.G.; Albright, K.; Weiss, B.D.; Brach, C.; West, D. Demonstration of the Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit: Lessons for Quality Improvement. J. Ambul. Care Manag. 2016, 39, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| School | Date of Parent Interview | Location | SEIFA †,‡ Decile | Number Children | Number of Parents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 22/11/2017 | Inner Regional | 8 | 297 | 2 |

| 2 | 6/11/2018 | Inner Regional | 2 | 289 | 2 |

| 3 | 20/11/2018 | Inner Regional | 7 | 597 | 1 |

| 4 | 21/11/2018 | Outer Regional | 2 | 366 | 2 |

| TOTAL | 7 |

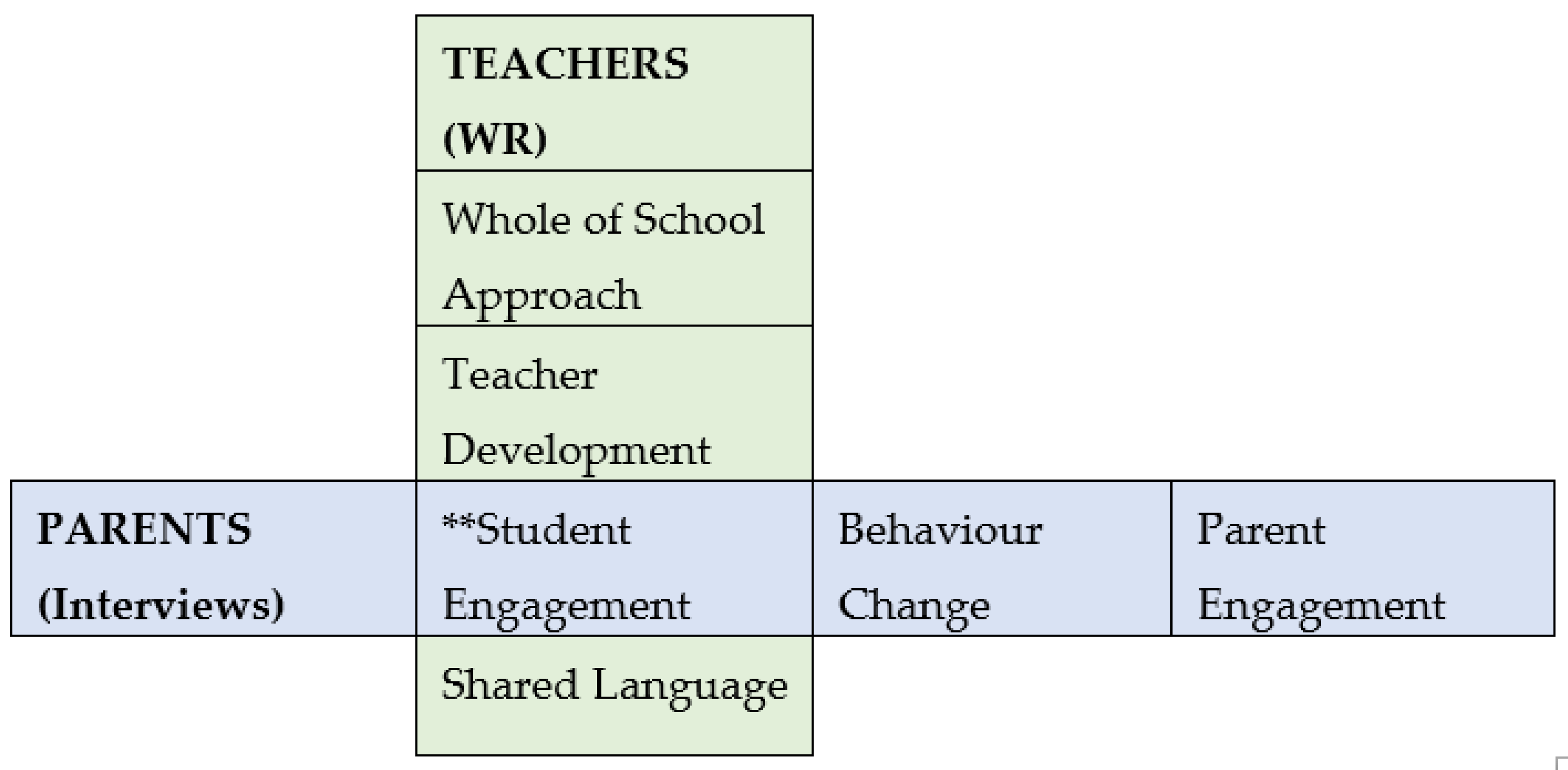

| Words | Example Quote | Sub Themes | Themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Love | Arabella loves going out there and grabbing stuff out of the garden and going into the kitchen and cooking. | Physical Activities | Student Engagement |

| They [children] love walking, exercising, riding bikes—they know what’s good for them. I can’t argue with that. | |||

| Games and sport, they loved trying the yoga at the expo. Lots of kids commented on that. | Practical Activities | ||

| Excited | I know they did snow globes. Yeah, and he was really excited to make his snow globe. | ||

| Great time | My son’s class did healthy lunchboxes. They loved it. They had a great time doing that and it was really good. | ||

| Fruit | And he’s now only put two pieces of fruit in his lunchbox for recess and that was his choice. It made a huge difference to him. | Diet | Behaviour Change |

| We’ve certainly got a lot more fruit in the house. They’ve even been having a piece of fruit for dessert, we have icy-poles and ice-cream in the fridge, but they’ll go and a couple of times Jordan said, “Well we’re better off to have a piece of fruit” and he’ll go and do that, so it’s been great. | |||

| Salad | So my son, his diet changed a little bit in terms of tacos to wraps. He’ll eat a salad for lunch, so that’s been an outcome which is good. | ||

| Bike | He’s done some research and he wants a new bike, because he’ll use his bike and it’s good exercise. His friends have organised to go to the pool a couple of times and he said, “That’s good exercise, mum.” | Exercise | |

| It’s made a big impact on Jordan because they counted their calories about what they ate over a couple of days, and it affected him hugely he now thinks about he actually said, “I’ve had a thousand more calories today than what I should have had, because I’ve had Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC). You need to take me for a bike ride.” And that is amazing. | |||

| Calm | There are a few times when I get a bit stressed, you know, of a morning, come on, and she’d say to me, “Oh, maybe you should get one of the things out of the carton of calm and look,”. So I feel like she’s really taking it in and putting it into practice as well. | Mental health | |

| Sugar | I’ve seen Abby have a look—in the last few weeks she’s been looking on the back of packets to see how much sugar’s in it, because she said, “I should only have six teaspoons a day,” and she said, “I’m only going to put half a teaspoon on top of my Weetbix instead of a whole teaspoon.” | Nutritional Information | |

| One of the main things that my daughter’s class did was looked at the side of the cereal boxes and they compared them, so how much sugar and how much salt. So after that she came home and she got out our cereal boxes and compared, and so that was one thing that I really thought yeah, that’s good. | |||

| Fair | I think having the artefacts at the fair, that was a lot of excitement and it was very beautiful. | Celebration | Parent Engagement |

| So normally at a school fair it’s a sausage and it’s a barbecue and there’s face painting and all that, but to actually have some school content in there as well, I thought that was absolutely fantastic. They’re really, really good. | |||

| Show | That afternoon, when it was open for the parents to come in, the fact that there were things for the children to show that they’d been doing, got a lot more parents in than what we would’ve had otherwise, so I think that’s a really good idea. | ||

| Idea | Tracy (Teacher) did that cook book with all the different healthy [lunches and stuff] which is a really good idea because there are a few lunchboxes that are all pre-packaged high sugar. | Healthy Ideas | |

| Even where they had that wall of lunchbox ideas, if they had little booklets of healthy lunchbox ideas or recipes. Something that encourages parents to actually take on a bit of healthier habit. | |||

| Invite | Maybe when each class was doing their projects, if parents had been invited to be involved, I think that they would’ve been more likely to. I think some parents are a bit funny about not really knowing when to offer to do parent help. | Invitation | |

| Where parents know that they’re actually invited to be part of something particular that benefits their child and their family, I think is how to get some of those people that are not naturally community minded. | |||

| Informed | I think maybe just keep everybody informed. Everybody saw the ad in the newsletter that there was a health literacy expo coming but I don’t know that they necessarily really knew what was going on before that, to then know what it was about. | School-Parent Communication | |

| Principal | It was in the principal’s report last time, she mentioned the types of things that’d happened and how great it was. | ||

| Newsletter | Probably there’s been some communication through the school app, so if there hasn’t been then there’s an opportunity there. I think it was in the school newsletter through the apps. That’s another good thing. | ||

| Discuss | When she brought the plate home she’d go through the foods on her plate and she explained to me why salami’s a sometimes food and stuff like that and how all the vegetables are always foods. There was a lot of discussion around food. | Student-Parent Communication | |

| [Millie] would discuss things with me. The girls will jump in the car and tell us exactly what happened every day at school. | |||

| Involved | I think one thing we do need to try and find is a way to get more parents involved doing stuff | Time | |

| We struggle to get parents to get involved. I think it’s a time thing. There’s a lot of people that are—where both parents are working. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nash, R.; Cruickshank, V.; Flittner, A.; Mainsbridge, C.; Pill, S.; Elmer, S. How Did Parents View the Impact of the Curriculum-Based HealthLit4Kids Program Beyond the Classroom? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041449

Nash R, Cruickshank V, Flittner A, Mainsbridge C, Pill S, Elmer S. How Did Parents View the Impact of the Curriculum-Based HealthLit4Kids Program Beyond the Classroom? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(4):1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041449

Chicago/Turabian StyleNash, Rosie, Vaughan Cruickshank, Anna Flittner, Casey Mainsbridge, Shane Pill, and Shandell Elmer. 2020. "How Did Parents View the Impact of the Curriculum-Based HealthLit4Kids Program Beyond the Classroom?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 4: 1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041449

APA StyleNash, R., Cruickshank, V., Flittner, A., Mainsbridge, C., Pill, S., & Elmer, S. (2020). How Did Parents View the Impact of the Curriculum-Based HealthLit4Kids Program Beyond the Classroom? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(4), 1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041449