Visitor Engagement, Relationship Quality, and Environmentally Responsible Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

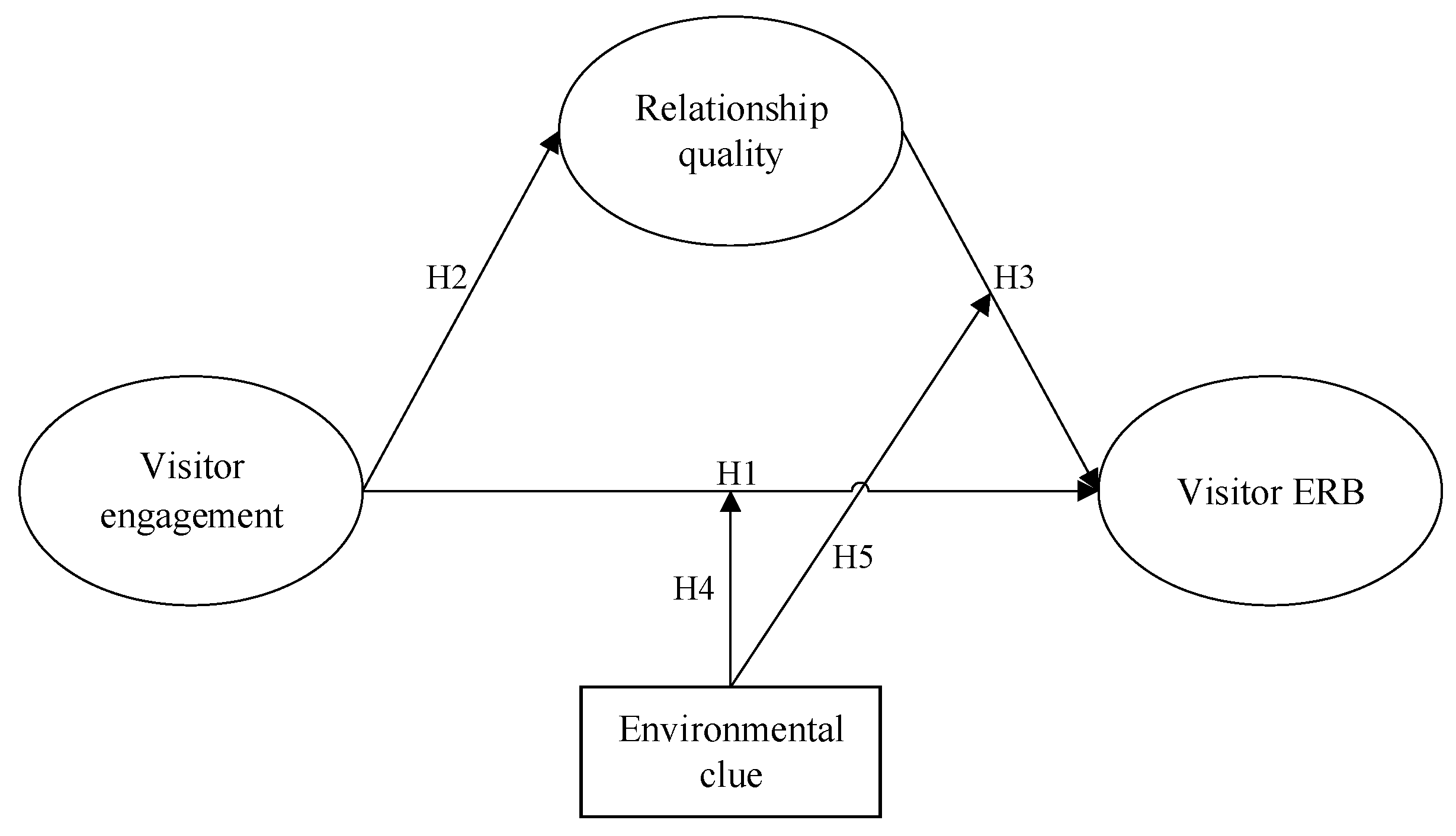

2. Theory and Hypothesized Model

2.1. Visitor Engagement and Their Environmentally Responsible Behavior

2.2. Visitor Engagement and the Quality of Relationship between Visitors and Destination

2.3. Relationship Quality and Visitor Environmentally Responsible Behavior

2.4. Moderating Role of Destinations’ Environmental Clues

3. Measurement and Data Collection

3.1. Measures

3.2. Data Collection and Sample

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

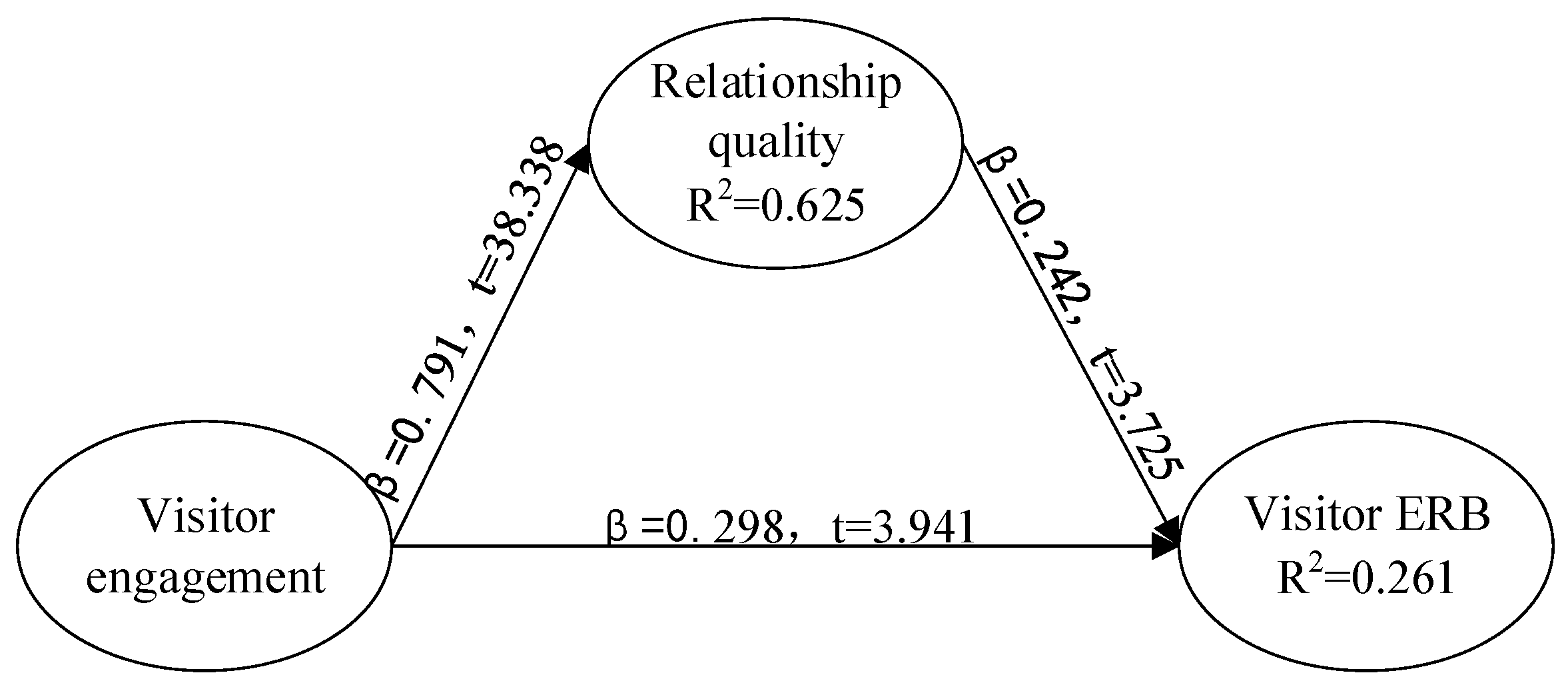

4.2. Structural Model

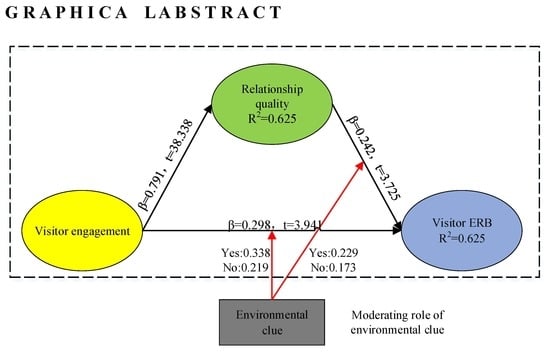

4.3. Moderating Role of Environmental Clue

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, C.; Zhang, J.H.; Cao, J.J.; Duan, X.F.; Hu, Q.X. The impact of behavioral reference on tourists’ responsible environmental behaviors. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 694, 133698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logar, I. Sustainable tourism management in Crikvenica, Croatia: An assessment of policy instruments. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J.; Sutherland, L.A. Visitors’ memories of wildlife tourism: Implications for the design of powerful interpretive experiences. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Wang, D.; Park, E. Social impacts as a function of place change. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 50, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.M.; Wu, H.C. How do environmental knowledge, environmental sensitivity, and place attachment affect environmentally responsible behavior? An integrated approach for sustainable island tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 557–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Edu. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H.; Yang, C.C. Conceptualizing and measuring environmentally responsible behavior from the perspective of community-based tourists. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Travelers’ pro-environmental behavior in a green lodging context: Converging value-belief-norm theory and the theory of planned behavior. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.T.; Wu, X.G.; Zhang, Y.L.; Wang, Y. Factors driving environmentally responsible behaviors by tourists: A case study of Taiwan China. Tour. Trib. 2015, 30, 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Pan, L.; Dogan, G. Persuasiveness of Signboard Messages in Scenic Spots: The Impact of Linguistic Style and Color Valence. Tour. Trib. 2016, 31, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.; Liu, J.L.; Tang, N.; Zhang, T. The influence of values and scenic spot’s policy on tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior: An extended theory of planned behavior model. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2018, 32, 88–94. [Google Scholar]

- Bamberg, S. How does environmental concern influence specific environmentally related behaviors? A new answer to an old question. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Sun, P.S.; Zhao, F.Z.; Han, X.H.; Yang, G.H.; Feng, Y.Z. Analysis of the ecological conservation behavior of farmers in payment for ecosystem service programs in eco-environmentally fragile areas using social psychology models. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 550, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Untaru, E.N.; Epuran, G.H.; Ispas, A. A conceptual framework of consumers’ pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors in the tourism context. Econ. Sci. 2014, 56, 86–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Wang, X.M.; Guo, D.X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z.H. Analysis of factors influencing residents’ habitual energy-saving behaviour based on NAM and TPB models: Egoism or altruism? Energy Policy 2018, 116, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGroot, J.I.M.; Steg, L. Morality and pro-social behavior: The role of awareness, responsibility and norms in the norm activation model. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 149, 425–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiatkawsin, K.; Han, H. Young travelers’ intention to behave pro-environmentally: Merging the value-belief-norm theory and the expectancy theory. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case for environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Landon, A.C.; Woosnam, K.M.; Bynum, B. Modeling the psychological antecedents to tourists’ pro-sustainable behaviors: An application of the value-belief-norm model. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 957–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, C. Tourists’ perceptions of responsibility: An application of norm-activation theory. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.J.; Hsu, M.K.; Boostrom, R.E. From recreation to responsibility: Increasing environmentally responsible behavior in tourism. J. Bus. Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpenny, E.A. Pro-environmental behaviors and park visitors: The effect of place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Weiler, B.; Smith, L.D.G. Place attachment and pro-environmental behavior in national parks: The development of a conceptual framework. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonge, J.; Ryan, M.M.; Moore, S.A.; Beckley, L.E. The effect of place attachment on pro-environment behavioral intentions of visitors to coastal natural area tourist destinations. J. Travel Res. 2014, 54, 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Guo, D.D. Why the Failure to Prohibit Tourists’ “I Was Here” Graffiti Behavior is Repeated? The Perspective of Moral Identity. Tour. Trib. 2018, 33, 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, H.L.; Fan, J.; Zhao, L. Development of the Academic Study of Tourists’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior: A Literature Review. Tour. Trib. 2018, 33, 122–138. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, J.J.; Dong, X.W.; Bao, B.L. A Logical Disentangling of the Concept “Unusual Environment” and Its Influence on Tourist Behavior. Tour. Trib. 2018, 33, 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum, A. The Constant Customer, Gallup Management Journal. 2001. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/businessjournal/745/constant-customer.aspx (accessed on 6 October 2018).

- Verhoef, P.C.; Reinartz, W.; Krafft, M. Customer Engagement as a New Perspective in Customer Management. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thunderhend. Engagement 3.0: A New Model for Customer Engagement. 2014. Available online: http://www.thunderhead.com/customer-engagement/customer-engagement-3.0-us/ (accessed on 6 October 2018).

- Brodie, R.J.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Juric, B.; Ilic, A. Customer Engagement: Conceptual Domain, Fundamental Propositions & Implications for Research. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 252–271. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie, R.J.; Ilic, A.; Juric, B.; Hollebeek, L.D. Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: An exploratory analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessart, L.; Veloutsou, C.; Morgan-Thomas, A. Consumer engagement in online brand communities: A social media perspective. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2015, 24, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D. Exploring customer brand engagement: Definition and themes. J. Strateg. Mark. 2011, 19, 555–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Glynn, M.S.; Brodie, R.J. Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. J. Interact. Mark. 2014, 28, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, J.; Lemon, K.N.; Mittal, V.; Nass, S.; Pick, D.; Pirner, P.; Verhoef, P.C. Customer engagement behavior: Theoretical foundations and research directions. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, J.L.H. The process of customer engagement: A conceptual framework. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2009, 17, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrigan, P.; Evers, U.; Miles, M.; Daly, T. Customer engagement with tourism social media brands. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, R. Understanding customer engagement and loyalty: A case of mobile devices for shopping. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 32, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMatos, C.A.; Rossi, C.A. Word-of-Mouth Communications in Marketing: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Antecedents and Moderators. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 578–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.R.R. Perceived values of branded mobile media, consumer engagement, business-consumer relationship quality and purchase intention: A study of WeChat in China. Public Relat. Rev. 2017, 43, 945–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.Y.; Tian, T.; Sun, B.L. A “Perception-Identity-Engagement” Model for the Tourism Virtual Community. Tour. Trib. 2016, 31, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Vivek, S.D.; Beatty, S.E.; Morgan, R.M. Consumer Engagement: Exploring Customer Relationships beyond Purchase. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2012, 20, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.H.; Hua, D.B.; Scott, R.S. Destination perceptions, relationship quality, and tourist environmentally responsible behavior. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.H.; Hu, D.B.; Su, L.J. Destination Resident’s Perceived Justice, Relational Quality, and Environmentally Responsible Behavior. Tour. Trib. 2018, 33, 117–131. [Google Scholar]

- Jiseon, A.; Ki-Joon, B. Antecedents and consequences of customer brand engagement in integrated resorts. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 75, 144–152. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.Y.; Xu, C.X.; Wang, K.Y. Tourist engagement with a destination: Conceptualization and scale development. Resour. Sci. 2019, 41, 441–453. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, Y. The Influence of Brand Engagement on Brand Relationship Quality and Repurchase Intention. Tour. Trib. 2017, 32, 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kanchanapibul, M.; Lacka, E.; Wang, X.J.; Chan, H.K. An empirical investigation of green purchase behavior among the young generation. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.R.; Chapman, R. Thinking like a park: The effects of sense of place, perspective-taking, and empathy on pro-environmental intentions. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2003, 21, 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.L.; Lyu, J.Y. Inspiring awe through tourism and its consequence. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 77, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, N.N.; Li, D.F. A Literature Review of Customer Engagement. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2015, 37, 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Aksoy, L.; Donkers, B.; Venkatesan, R.; Wiesel, T.; Tillmanns, S. Undervalued or Overvalued Customers: Capturing Total Customer Engagement Value. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Pansari, A. Competitive advantage through engagement. J. Mark. Res. 2016, 53, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Kim, K.H. Role of consumer relationships with a brand in brand extensions: Some exploratory findings. ACR N. Am. Adv. 2001, 1, 179–185. [Google Scholar]

- Al-alak, B.A. Impact of marketing activities on relationship quality in the Malaysian banking sector. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 221, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.G.; Cha, Y. Antecedents and consequences of relationship quality in hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2002, 21, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Head, M. Consumer relationship marketing on the Internet: An overview and clarification of concept. Innov. Mark. 2005, 1, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- So, K.K.F.; King, C.; Sparks, B. Customer engagement with tourism brands: Scale development and validation. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2014, 38, 304–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.L.; Green, J.D.; Reed, A. Interdependence with the environment: Commitment, interconnectedness, and environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.J.; Swanson, S.R. The effect of destination social responsibility on tourist environmentally responsible behavior: Compared analysis of first-time and repeat tourists. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.; Malhotra, N.K.; Kim, Y.; Tomiuk, M.A.; Hong, S.J. A comparative study on parameter recovery of three approaches to structural equation modeling. J. Mark. Res. 2010, 47, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.K. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Techniques Using Smart PLS. Mark. Bull. 2013, 24, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L.; Zhang, T.H.; Fu, Y. Urban Residents’ Cognition of Haze-fog Weather and Its Impact on Their Urban Tourism Destination Choice. Tour. Trib. 2015, 30, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Machine Press: Beijing, China, 2011; p. 709. [Google Scholar]

- Urbach, N.; Ahlemann, F. Structural equation modeling in information systems research using partial least squares. J. Inform. Technol. Theory App. 2010, 2, 5–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzels, M.; Odekerken-Schröder, G.; Van Oppen, C. Using PLS path modelling for assessing hierarchical construct models: Guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Science, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, M. Cross-validatory choice and assessment of statistical predictions. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1974, 36, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K.M.; Aleshinloye, K.D. Can tourists experience emotional solidarity with residents? Testing Durkheim’s model from a new perspective. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 494–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K.M.; Shafer, C.S.; Scott, D.; Timothy, D.J. Tourists’ perceived safety through emotional solidarity with residents in two Mexico–United States border regions. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | n | % | Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Monthly Income | ||||

| Male | 201 | 49.0 | Less than 5000RMB | 190 | 46.3 |

| Female | 209 | 51.0 | 5001–8000 | 100 | 24.4 |

| Age (years) | 8001–17,000 | 88 | 21.5 | ||

| 18–30 | 190 | 46.3 | 17,001–40,000 | 28 | 6.8 |

| 31–40 | 159 | 38.8 | More than 40,000 | 4 | 1.0 |

| 41–50 | 37 | 9.0 | Level of Education | ||

| 51 or Older | 24 | 5.9 | Less than High School | 4 | 1.0 |

| High school/Technical school | 135 | 32.9 | |||

| Undergraduate/Associate Degree | 260 | 63.4 | |||

| Postgraduate Degree | 11 | 2.7 |

| Constructs and Scale Items | Factor Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Visitor Engagement | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.51 | |

| I think about the destination while visiting it | 0.54 | |||

| I would like to learn more about the destination | 0.51 | |||

| I think about the destination even after visiting it | 0.67 | |||

| I feel very positive when I visit the destination | 0.79 | |||

| Visiting the destination makes me happy | 0.80 | |||

| I feel great when I visit the destination | 0.83 | |||

| I am very proud to visit the destination | 0.76 | |||

| I would like to spend more time in the destination | 0.78 | |||

| I would like to visit the destination frequently | 0.82 | |||

| I would like to pay more attention to the destination | 0.66 | |||

| 2. Relationship Quality | 0.87 | 0.91 | 0.67 | |

| I am committed to keeping the best interests of the environment in mind at the destination | 0.73 | |||

| I am interested in strengthening my connection to the environment of the destination in future | 0.89 | |||

| I feel very attached to the environment of the destination | 0.82 | |||

| I expect that I will always feel a strong connection with the environment of the destination | 0.85 | |||

| I am satisfied with my visit to the destination | 0.79 | |||

| 3. Visitor Environmentally Responsible Behavior | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.63 | |

| I would like to follow the legal policies of the destination and scenic spot | 0.80 | |||

| I would like to dispose of the garbage properly during my trip | 0.84 | |||

| I would like to protect the plants and animals of the destination and scenic spot | 0.87 | |||

| I would like to protect the relics and facilities of the destination and scenic spot | 0.87 | |||

| I would like to encourage others to follow the legal policies of the destination and scenic spot | 0.85 | |||

| I would like to encourage others to protect the environment of the destination and scenic spot | 0.80 | |||

| When I see garbage from others, I will pick them up and put them in the trash | 0.57 | |||

| I try to stop others from damaging the environment of the destination and scenic spot | 0.67 |

| Scale Items | Visitor Engagement | Relationship Quality | Visitor ERB |

|---|---|---|---|

| I think about the destination while visiting it | 0.54 | 0.38 | 0.29 |

| I would like to learn more about the destination | 0.51 | 0.35 | 0.38 |

| I think about the destination even after visiting it | 0.67 | 0.48 | 0.36 |

| I feel very positive when I visit the destination | 0.79 | 0.57 | 0.41 |

| Visiting the destination makes me happy | 0.80 | 0.59 | 0.44 |

| I feel great when I visit the destination | 0.83 | 0.61 | 0.39 |

| I am very proud to visit the destination | 0.76 | 0.63 | 0.30 |

| I would like to spend more time in the destination | 0.78 | 0.64 | 0.33 |

| I would like to visit the destination frequently | 0.82 | 0.63 | 0.29 |

| I would like to pay more attention to the destination | 0.66 | 0.59 | 0.26 |

| I am committed to keeping the best interests of the environment in mind at the destination | 0.55 | 0.73 | 0.42 |

| I am interested in strengthening my connection to the environment of the destination in future | 0.67 | 0.89 | 0.35 |

| I feel very attached to the environment of the destination | 0.58 | 0.82 | 0.35 |

| I expect that I will always feel a strong connection with the environment of the destination | 0.62 | 0.85 | 0.29 |

| I am satisfied with my visit to the destination | 0.65 | 0.79 | 0.48 |

| I would like to follow the legal policies of the destination and scenic spot | 0.37 | 0.36 | 0.80 |

| I would like to dispose of the garbage properly during my trip | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.84 |

| I would like to protect the plants and animals of the destination and scenic spot | 0.39 | 0.35 | 0.87 |

| I would like to protect the relics and facilities of the destination and scenic spot | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.87 |

| I would like to encourage others to follow the legal policies of the destination and scenic spot | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.85 |

| I would like to encourage others to protect the environment of the destination and scenic spot | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.80 |

| When I see garbage from others, I will pick them up and put them in the trash | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.57 |

| I try to stop others from damaging the environment of the destination and scenic spot | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.67 |

| Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Visitor Engagement | [0.71] | ||

| 2. Relationship Quality | 0.70 | [0.82] | |

| 3. Visitor Environmentally Responsible Behavior | 0.49 | 0.48 | [0.79] |

| Predicted Relationships | Standard Path Coefficient | T Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Clue | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Visitor engagement → Environmentally responsible behavior | 0.338 | 0.219 | 5.288 | 2.638 |

| Visitor engagement → Relationship quality | 0.741 | 0.764 | 30.994 | 33.811 |

| Relationship quality → Environmentally responsible behavior | 0.229 | 0.173 | 3.367 | 2.852 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, X.; Tang, C.; Lv, X.; Xing, B. Visitor Engagement, Relationship Quality, and Environmentally Responsible Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041151

Zhou X, Tang C, Lv X, Xing B. Visitor Engagement, Relationship Quality, and Environmentally Responsible Behavior. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(4):1151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041151

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Xiaoli, Chengcai Tang, Xingyang Lv, and Bo Xing. 2020. "Visitor Engagement, Relationship Quality, and Environmentally Responsible Behavior" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 4: 1151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041151

APA StyleZhou, X., Tang, C., Lv, X., & Xing, B. (2020). Visitor Engagement, Relationship Quality, and Environmentally Responsible Behavior. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(4), 1151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041151