Gender Norms, Roles and Relations and Cannabis-Use Patterns: A Scoping Review

Abstract

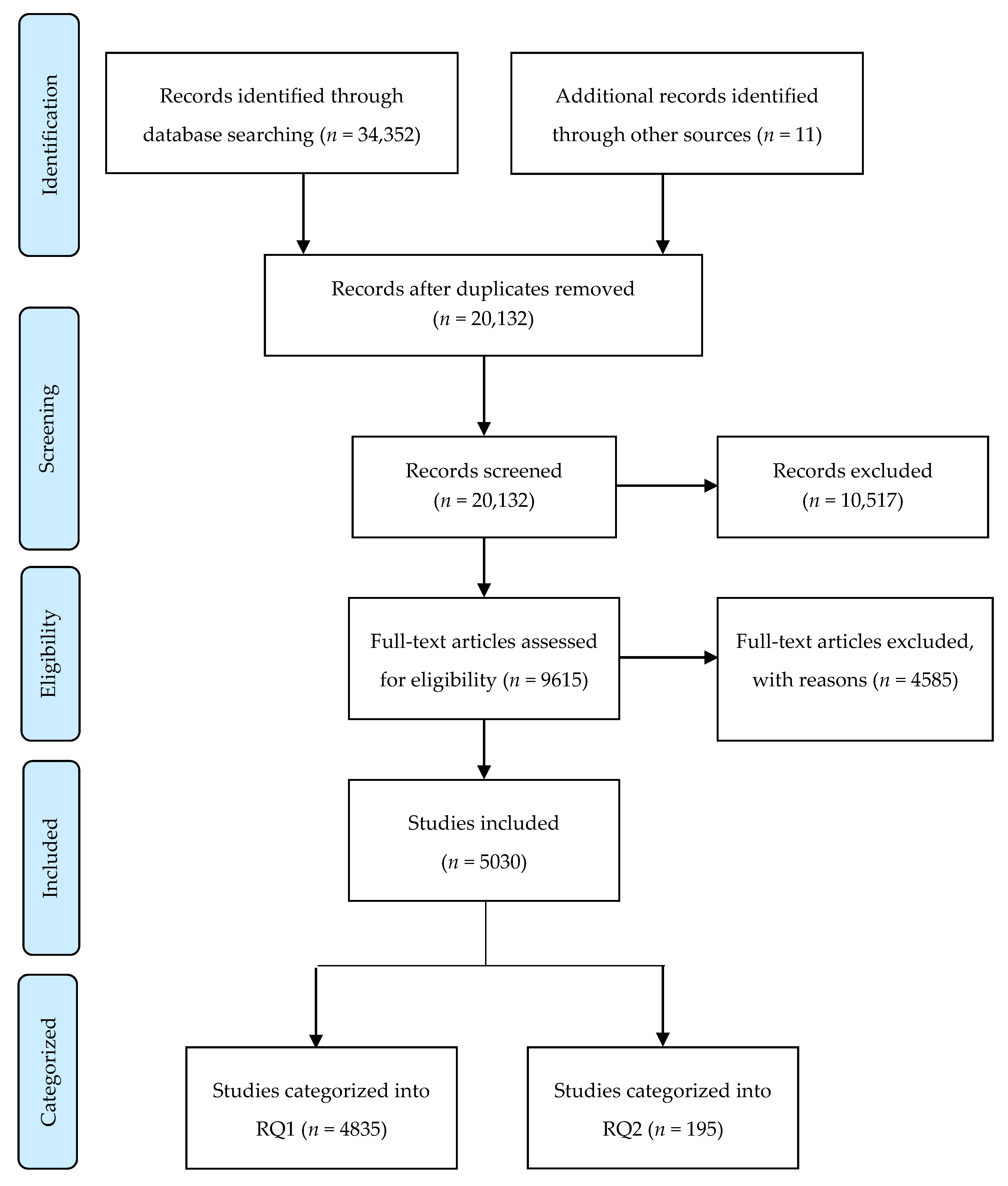

1. Introduction

Gender Norms, Roles and Relations

2. Methods

- (1)

- How do sex and gender related factors impact:

- (a)

- patterns of use;

- (b)

- health effects of;

- (c)

- and prevention/treatment/or harm reduction outcomes for opioid, alcohol, tobacco/nicotine and cannabis use?

- (2)

- What harm reduction, health-promotion/prevention and treatment interventions and programs are available that include sex, gender and gender transformative elements and how effective are these in addressing opioid, alcohol, tobacco/ nicotine and cannabis use?

3. Findings

4. Gender Norms

4.1. Male Typicality and Cannabis Use

4.2. Conformity to Feminine Norms

4.3. Conformity to Gender Norms, Culture and Acculturation

5. Gender Roles, Norms and Relations

5.1. Reinstating and Resisting Dominant Gender Norms

5.2. Cannabis and Gender Relations in Social Networks

“I have never really bought it. I always sort of smoke other people’s weed. Like I have this friend of mine. He is a really nice guy, and I usually smoke with him and his friends. They never let me pay, because they say I don’t smoke much…but I really think it’s because I am a girl and they are trying to be nice (laughs) (Female, 18).” [37] (p. 1675).

“Because a lot of the dealers are men and women have a lot of power of persuasion over men, especially if they are beautiful women. It’s easy for them to get what they want out of men, so there’s a bit of manipulation that goes on there” (p. 2034).

5.3. Cannabis Use in Intimate Relationships

‘Kara is the one that I’m quite fond of, she smokes in my bathroom at all the parties… So being able to steal Kara was very easy to do with just [saying to her] “Hey why don’t you come and have a conversation with me in my bathroom?” (Matthew, age 30) (p. 761).

5.4. Stigma and Discrimination

5.5. Stigma among Mothers and Fathers Who Use Cannabis

“When I was pregnant, I had morning sickness all day, every day for nine months, but I smoked only a few times. There was a strong social stigma against me. People told me not to smoke. (Paralegal, 41)” (p. 462).

“Smoking hash isn’t that dangerous, but being caught and stigmatized as a criminal—a criminal parent of young children; is that what I am? That is quite a poor starting point for being a family man, as you’re supposed to be” (p. 178).

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Database Search Strategies

| 1 | “gender transformative”. ti,ab. |

| 2 | (“gender informed” or “gender integrated” or “gender responsive”). ti,ab. |

| 3 | (“sex informed” or “sex integrated” or “sex responsive”). ti,ab. |

| 4 | (“gender equalit *” or “gender equit *” or “gender inequality *” or “gender inequit *”). ti,ab. |

| 5 | (“sex equalit *” or “sex equit *” or “sex inequality *” or “sex inequit *”). ti,ab. |

| 6 | (“gender related” or “gender difference *” or “gender disparit *”). ti,ab. |

| 7 | (“sex related” or “sex difference*” or “sex disparit*”).ti,ab. |

| 8 | “gender comparison *”. ti,ab. |

| 9 | “sex comparison *”. ti,ab. |

| 10 | “compar* gender *”. ti,ab. |

| 11 | “compar * sex *”. ti,ab. |

| 12 | “gender based”.ti,ab. |

| 13 | “sex based”.ti,ab. |

| 14 | (“gender divers *” or “gender minorit *”). ti,ab. |

| 15 | “gender analys *”. ti,ab. |

| 16 | “sex analys *”. ti,ab. |

| 17 | (transgender * or “trans gender *” or LGBQT or LGBTQ or LGBT or LGB or lesbian * or gay or bisexual * or queer *). ti,ab. |

| 18 | (“transsexual *” or “trans sexual *”).ti,ab. |

| 19 | 17 or 18 |

| 20 | (transgender * or “trans gender *” or LGBQT or LGBTQ or LGBT or LGB or lesbian * or gay or bisexual * or queer * or “transsexual *” or “trans sexual *”). ti,ab. |

| 21 | (“non binary *” or nonbinar *). ti,ab. |

| 22 | Homosex *. ti,ab. |

| 23 | (“woman focused” or “woman focussed” or “girl focused” or “girl focussed” or “woman centred” or “girl centred” or “woman centered” or “girl centered” or “female focused” or “female focussed” or “female centred” or “female centered”). ti,ab. |

| 24 | (“man focused” or “man focussed” or “boy focused” or “boy focussed” or “man centred” or “boy centred” or “man centered” or “boy centered” or “male focused” or “male focussed” or “male centred” or “male centered”). ti,ab. |

| 25 | Transgender Persons/ |

| 26 | Sexual Minorities/ |

| 27 | Transsexualism/ |

| 28 | Bisexuality/ |

| 29 | exp Homosexuality/ |

| 30 | Gender Identity/ |

| 31 | (bigender * or “bi gender *”). ti,ab. |

| 32 | (“gender identit *” or “gender incongru *”). ti,ab. |

| 33 | “differently gendered”. ti,ab. |

| 34 | or/1–33 [GENDER] |

| 35 | exp Opioid-Related Disorders/ |

| 36 | exp Analgesics, Opioid/ |

| 37 | (opioid * or opiate *). ti,ab. |

| 38 | (fentanyl or phentanyl or Fentanest or Sublimaze or Duragesic or Durogesic or Fentora or “R 4263” or R4263). ti,ab. |

| 39 | (oxycontin or oxycodone or oxycodan or percocet or percodan). ti,ab. |

| 40 | (heroin or morphine). ti,ab. |

| 41 | or/36–40 [OPIOIDS] |

| 42 | Prescription Drug Misuse/ or Prescription Drug Overuse/ |

| 43 | ((“prescription drug” or “prescription drugs” or “prescribed drug” or “prescribed drugs”) and (dependen * or misuse * or mis-use * or abuse * or overuse * or over-use * or addict *)). ti,ab. |

| 44 | exp Substance-Related Disorders/ |

| 45 | (“substance disorder *” or “substance related disorder *” or “substance use disorder *” or “drug use disorder *” or “drug related disorder *”). ti,ab. |

| 46 | (“over prescription” or “over prescribed”). ti,ab. |

| 47 | Drug Overdose/ or (overdose* or over-dose *).ti,ab. |

| 48 | or/42–47 |

| 49 | 35 or (41 and 48) |

| 50 | exp Alcohol-Related Disorders/ |

| 51 | exp Alcohol Drinking/ |

| 52 | (binge drink * or underage drink * or under-age drink * or problem drink * or heavy drink * or harmful drink * or alcoholi* or inebriat * or intoxicat *). ti,ab. |

| 53 | (“alcohol dependen *” or “alcohol misuse *” or “alcohol mis-use *” or “alcohol abuse *” or “alcohol overuse *” or “alcohol over-use *” or “alcohol addict *”). ti,ab. |

| 54 | alcohol. ti,ab. and (44 or 45) |

| 55 | Alcohol Abstinence/ |

| 56 | or/50–55 |

| 57 | “Tobacco Use Disorder”/ |

| 58 | Tobacco/ |

| 59 | Nicotine/ |

| 60 | exp Tobacco Products/ |

| 61 | exp “Tobacco Use”/ |

| 62 | ((cigar * or e-cigar * or tobacco or nicotine or smoking or vaping) and (dependenc * or misuse * or mis-use * or abuse * or overuse * or over-use * or addiction *)). ti,ab. |

| 63 | (58 or 59 or 60 or 61) and (44 or 45) |

| 64 | exp “Tobacco Use Cessation”/ |

| 65 | exp “Tobacco Use Cessation Products”/ |

| 66 | ((tobacco or smoking) and cessation). ti,ab. |

| 67 | or/57,62–66 |

| 68 | Marijuana Abuse/ |

| 69 | Cannabis/ |

| 70 | Marijuana Smoking/ |

| 71 | exp Cannabinoids/ |

| 72 | (marijuana or marihuana or hashish or ganja or bhang or hemp or cannabis or cannabinoid * or cannabidiol or tetrahydrocannabinol). ti,ab. |

| 73 | (69 or 70 or 71 or 72) and (43 or 44 or 45) |

| 74 | or/68,73 |

| 75 | or/49,56,67,74 |

| 76 | Harm Reduction/ |

| 77 | (“harm reduction” or “reducing harm” or “reducing harmful” or “harm minimization” or “minimizing harm” or “minimizing harmful” or “harm minimisation” or “minimising harm” or “minimising harmful”). ti,ab. |

| 78 | exp Risk Reduction Behavior/ |

| 79 | (“risk reduction” or “reducing risk” or “reducing risks” or “risk minimization” or “minimizing risk” or “minimizing risks” or “risk minimisation” or “minimising risk” or “minimising risks”). ti,ab. |

| 80 | or/76–79 |

| 81 | exp Health Promotion/ |

| 82 | (“health promotion” or “promoting health” or “promoting healthy” or “promoting wellness” or “patient education” or “consumer education” or “client education” or outreach or “wellness program” or “wellness programs” or “wellness programme” or “wellness programmes”). ti,ab. |

| 83 | 81 or 82 |

| 84 | Preventive Health Services/ |

| 85 | Consumer Health Information/ or Health Literacy/ |

| 86 | Secondary Prevention/ |

| 87 | (prevention or “preventive health” or “preventive healthcare”). ti,ab. |

| 88 | or/84-87 |

| 89 | (prevention or preventive). ti,ab. |

| 90 | 88 or 89 |

| 91 | Rehabilitation/ |

| 92 | (abstain * or abstinence or detox * or rehab * or sobriety or sober or temperance or intervention * or cessation or recovery). ti,ab. |

| 93 | Methadone/tu [Therapeutic Use] |

| 94 | “methadone maintenance”. ti,ab. |

| 95 | Opiate Substitution Treatment/ |

| 96 | (“opiate substitution” or “opioid substitution” or “withdrawal management” or “managing withdrawal”). ti,ab. |

| 97 | (treatment* or treating or therapy or therapies). ti,ab. |

| 98 | Intervention *. ti,ab. |

| 99 | or/91–98 |

| 100 | or/80,83,88,99 |

| 101 | or/80,83,90,99 |

| 102 | 34 and 75 and 101 |

| 103 | limit 102 to (english language and yr = “2007–2017”) [Limit not valid in Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR); records were retained] |

| 104 | (Animals/ or Animal Experimentation/ or “Models, Animal”/ or (animal * or nonhuman * or non human * or rat or rats or mouse or mice or rabbit or rabbit or pig or pigs or porcine or dog or dogs or hamster or hamsters or fish or chicken or chickens or sheep or cat or cats or raccoon or raccoons or rodent * or horse or horses or racehorse or racehorses or beagle *). ti,ab.) not (Humans/ or (human * or participant * or patient or patients or child * or seniors or adult or adults). ti,ab.) |

| 105 | 103 not 104 |

| 106 | (editorial or comment or letter or newspaper article). pt. |

| 107 | 105 not 106 |

| 108 | (conference or conference abstract or conference paper or “conference review” or congresses). pt. |

| 109 | 107 not 108EBM Reviews- Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews < 2005 to 2 August 2017 >Embase < 1980 to 3 August 2017 >Ovid MEDLINE(R) Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE(R) < 1946 to Present >EBM Reviews- Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials < July 2017 > |

| 110 | remove duplicates from 109EBM Reviews- Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews < 2005 to 2 August 2017 >Embase < 1980 to 3 August 2017 >Ovid MEDLINE(R) Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE(R) < 1946 to Present>EBM Reviews- Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials < July 2017 > |

| 111 | 110 use ppez [MEDLINE] |

| 112 | 110 use emezd [EMBASE] |

| 113 | 110 not (111 or 112) [selected 2 only as 13 were conference abstracts] |

- “gender determinant*” or “gender specific” were added to the gender/sex terms (see lines 1–33 in original search strategy)

- “alcohol use” or “use of alcohol” and “risky drink” were added to the alcohol terms

- The following terms were added to the gender/sex terms:(woman or man or women or men or girl or boy or girls or boys or trans or transgender or transgendered or female or male or sex or gender). ti. [GENDER IN TI]A search was then conducted of the article titles only, combining the following concepts:Search strategy:Concept 1—Gender/sex termsANDConcept 2—Substances (opioids, alcohol, tobacco, cannabis) termsANDConcept 3—Harm reduction, health promotion, prevention, treatment, health effects terms

- “heat not burn” was added to the tobacco terms.

- The search included studies published up until April 2018

Appendix B. Final Inclusion Criteria

- -

- randomised-controlled trials (RCTs) (not already covered in an included systematic review)

- -

- case-control studies

- -

- interrupted time series

- -

- cohort studies

- -

- cross sectional studies

- -

- observational studies

- -

- systematic reviews

- -

- qualitative studies

- -

- grey literature sources

- -

- case series

- -

- Narrative reviews will not be included but saved as context.

- -

- Case studies will be excluded.

- -

- book chapters

- -

- reports

- -

- practice guidelines

- -

- health policy documents

- -

- unpublished research, theses

- -

- Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States

- -

- Studies published in all other countries will be excluded, including animal studies.

- -

- Studies including data from multiple countries, that include an out of scope country, will be excluded if the data is not disaggregated.

- -

- Systematic reviews which include studies from multiple countries will be included if reporting on one or more studies published in an eligible country.

- -

- The literature search will cover studies published between 2007 to 2017

- -

- Only studies published in the English language will be included.

- (a)

- patterns of use;

- (b)

- health effects of;

- (c)

- and prevention/treatment/or harm reduction outcomes for opioid, alcohol, tobacco and cannabis use?

- -

- Women, girls, men, boys, trans people/ gender diverse people

- -

- All ages, demographics within the defined populations

- -

- Studies that are conducted primarily with pregnant girls and women will be excluded.

- -

- Studies addressing the fetal health effects of maternal/ paternal substance use will be excluded.

- -

- Studies addressing the health effects of substance use on the infant among women who are breastfeeding will be excluded.

- -

- Studies comparing heterosexual populations to LGBT populations, without sex or gender disaggregation will be excluded.

- -

- Inclusive of tobacco in general (include e-cigarettes)

- -

- Inclusive of all alcohol use (not just binge drinking)

- -

- Inclusive of all opioid use issues (include illicit use/heroin, prescription opioids, etc.)

- ▪

- Opioid use for cancer pain management will be excluded

- -

- Inclusive of all purposes (therapeutic and recreational), forms and modes of ingestion of cannabis (e.g., smoking, vaping, edibles, extracts, etc.).

- -

- Studies that report on “substance use” but do not disaggregate results by one or more of the four substances in our review will be excluded.

- -

- Studies that report on “substance use” but do not disaggregate results by one or more of the four substances in our review will be excluded.

- -

- Opioid substitution therapy for substances other than opioids (e.g., cocaine, methamphetamine) will be excluded

- -

- Many Q1 (a) and (b) studies will be descriptive/ prevalence studies (not intervention studies) and may not include a comparator.

- -

- Many qualitative and grey literature sources will likely not include comparators

- -

- Q1 (c) studies must include a comparison between gender groups e.g., women vs. men; sub-groups of women/ men OR if sex- or gender- based factors are described or discussed in the study (e.g., masculinity norms, hormones etc.). Q1c studies that do not compare gender groups or describe sex- or gender-based factors will be excluded.

- -

- For non-intervention studies: prevalence/patterns of use (frequency of use, form and method of ingestion, etc.);

- -

- For intervention studies (Q1c): outcomes reported in the reviews will be the outcomes that are reported in the individual papers that are reviewed. Relevant outcomes from the included studies might include:

- -

- Changes in substance use (uptake/initiation, harms associated with use cessation, reduction)

- -

- Changes in client perceptions/attitudinal change

- -

- Changes in service provider perceptions

- -

- Changes in retention/treatment completion

- -

- Increased use of services

- -

- improved health and quality of life outcomes

- -

- Women, girls, men, boys, trans people/gender-diverse people

- -

- All ages, demographics within the defined populations

- -

- Studies that are conducted primarily with pregnant girls and women will be excluded.

- -

- Studies addressing the fetal health effects of maternal/paternal substance use will be excluded.

- -

- Studies addressing the health effects of substance use on the infant among women who are breastfeeding will be excluded.

- -

- Harm reduction, health promotion, prevention, treatment (including brief intervention) responses to opioids, alcohol, cannabis, tobacco/e-cigarettes including some sex, gender and/or gender transformative elements

- -

- Studies that report on ‘substance use’ will be included if they potentially contain one of the four substances. However, if substance use is defined, and does not contain alcohol, tobacco, opioids or cannabis it will be excluded.

- -

- Opioid substitution therapy for substances other than opioids (e.g., cocaine, methamphetamine) will be excluded.

- -

- Examples of sex specific elements (address biological differences in substance use and dependence):

- -

- administering different types or quantities of pharmacotherapies based on evidence of biological differences in drug metabolism/effectiveness

- -

- timing tobacco-cessation intervention for young women based on the menstrual cycle (hormonal fluctuations impact withdrawal)

- -

- Examples of possible gender/gender-transformative elements:

- -

- address gender-based violence

- -

- provide social support

- -

- address caregiving

- -

- address poverty

- -

- address negative gender stereotypes

- -

- include education or messaging on gender norms/relations

- -

- address employment issues/work-related stress

- -

- address discrimination and violence related to gender identity

- -

- Inclusive of tobacco in general (include e-cigarettes)

- -

- Inclusive of all alcohol use (not just binge drinking)

- -

- Inclusive of all opioid use issues (include illicit use/heroin, prescription opioids, etc.)

- ▪

- Opioid use for cancer pain management will be excluded

- -

- Inclusive of all purposes (therapeutic and recreational), forms and modes of ingestion of cannabis (e.g., smoking, vaping, edibles, extracts, etc).

- -

- No intervention or usual practice (i.e., interventions that are not gender-informed/gender-transformative, sex-specific), or the comparison of two intervention types.

- -

- Many qualitative and grey literature sources will likely not include comparators.

- -

- Outcomes reported in the reviews will be the outcomes that are reported in the individual papers that are reviewed. Relevant outcomes from the included studies might include:

- -

- Changes in substance use (uptake/initiation, harms associated with use, cessation, reduction)

- -

- Changes in client perceptions/attitudinal change

- -

- Changes in service provider perceptions

- -

- Changes in retention/treatment completion

- -

- Increased use of services

- -

- improved health and quality of life outcomes

- -

- changes in health and gender equity

References

- Cranford, J.A.; Eisenberg, D.; Serras, A.M. Substance use behaviors, mental health problems, and use of mental health services in a probability sample of college students. Addict. Behav. 2009, 34, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carliner, H.; Mauro, P.M.; Brown, Q.L.; Shmulewitz, D.; Rahim-Juwel, R.; Sarvet, A.L.; Wall, M.M.; Martins, S.S.; Carliner, G.; Hasin, D.S. The widening gender gap in marijuana use prevalence in the U.S. During a period of economic change, 2002–2014. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017, 170, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felton, J.W.; Collado, A.; Shadur, J.M.; Lejuez, C.W.; MacPherson, L. Sex differences in self-report and behavioral measures of disinhibition predicting marijuana use across adolescence. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2015, 23, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmer, R.F.; Kosty, D.B.; Seeley, J.R.; Duncan, S.C.; Lynskey, M.T.; Rohde, P.; Klein, D.N.; Lewinsohn, P.M. Natural course of cannabis use disorders. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, R.M.; Fairman, B.; Gilreath, T.; Xuan, Z.M.; Rothman, E.F.; Parnham, T.; Furr-Holden, C.D.M. Past 15-year trends in adolescent marijuana use: Differences by race/ethnicity and sex. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015, 155, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuttler, C.; Mischley, L.K.; Sexton, M. Sex differences in cannabis use and effects: A cross-sectional survey of cannabis users. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2016, 1, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggio, S.; Deline, S.; Studer, J.; Mohler-Kuo, M.; Daeppen, J.B.; Gmel, G. Routes of administration of cannabis used for nonmedical purposes and associations with patterns of drug use. J. Adol. Health 2014, 54, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniulaityte, R.; Zatreh, M.Y.; Lamy, F.R.; Nahhas, R.W.; Martins, S.S.; Sheth, A.; Carlson, R.G. A twitter-based survey on marijuana concentrate use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018, 187, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, K.G.; Dilks, L.M. Marijuana, gender, and health-related harms: Disentangling marijuana’s contribution to risk in a college “party” context. Sociol. Spectr. 2015, 35, 254–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, G.; Asmussen Frank, V.; Moloney, M. Rethinking gender within alcohol and drug research. Subst. Misuse 2015, 50, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legleye, S.; Piontek, D.; Pampel, F.; Goffette, C.; Khlat, M.; Kraus, L. Is there a cannabis epidemic model? Evidence from France, Germany and USA. Int. J. Drug Policy 2014, 25, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, J.K.; Fish, J.N.; Perez-Brumer, A.; Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Russell, S.T. Transgender youth substance use disparities: Results from a population-based sample. J. Adol. Health 2017, 20, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keuroghlian, A.S.; Reisner, S.L.; White, J.M.; Weiss, R.D. Substance use and treatment of substance use disorders in a community sample of transgender adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015, 152, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Poole, N.; Greaves, L.; Hemsing, N. New terrain: Tools to Integrate Trauma and Gender Informed Responses into Substance Use Practice and Policy 2018; Centre of Excellence for Women‘s Health: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Budgeon, S. The dynamics of gender hegemony: Femininities, masculinities and social change. Sociology 2014, 48, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, D.; Manohar, N.N.; Tinkler, J.E. Walk like a man, talk like a woman: Teaching the social construction of gender. Teach. Sociol. 2010, 38, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, L.; Hemsing, N. Sex and gender interactions on the use and impact of recreational cannabis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creighton, G.; Oliffe, J.L. Theorising masculinities and men’s health: A brief history with a view to practice. Health Sociol. Rev. 2010, 19, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, J.; Iwamoto, D.K.; Grivel, M.; Kaya, A.; Clinton, L. A systematic review of the salient role of feminine norms on substance use among women. Addict. Behav. 2016, 62, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, A.L.; Fleming, P.J.; Halpern, C.T.; Herring, A.H.; Harris, K.M. Adherence to gender-typical behavior and high frequency substance use from adolescence into young adulthood. Psychol. Men Masc. 2018, 19, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, R.K.; Votaw, V.R.; Sugarman, D.E.; Greenfield, S.F. Sex and gender differences in substance use disorders. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 66, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdes, Z.T.; Levant, R.F. Complex relationships among masculine norms and health/well-being outcomes: Correlation patterns of the conformity to masculine norms inventory subscales. Am. J. Men Health 2018, 12, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwamoto, D.K.; Corbin, W.; Lejuez, C.; MacPherson, L. College men and alcohol use: Positive alcohol expectancies as a mediator between distinct masculine norms and alcohol use. Psychol. Men Masc. 2014, 15, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everitt-Penhale, B.; Ratele, K. Rethinking ‘traditional masculinity’as constructed, multiple, and hegemonic masculinity. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2015, 46, 4–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, A.L.; Halpern, C.T.; Herring, A.H.; Shanahan, M.; Ennett, S.T.; Hussey, J.M.; Harris, K.M. Testing longitudinal relationships between binge drinking, marijuana use, and depressive symptoms and moderation by sex. J. Adol. Health 2016, 59, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Methods for the Development of NICE Public Health Guidance; NICE: London, UK, 2012.

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Reprint—Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Phys. Ther. 2009, 89, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalik, J.R.; Lombardi, C.M.; Sims, J.; Coley, R.L.; Lynch, A.D. Gender, male-typicality, and social norms predicting adolescent alcohol intoxication and marijuana use. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 143, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulis, S.; Marsiglia, F.F.; Lingard, E.C.; Nieri, T.; Nagoshi, J. Gender identity and substance use among students in two high schools in Monterrey, Mexico. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008, 95, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulis, S.; Marsiglia, F.F.; Nagoshi, J.L. Gender roles, externalizing behaviors, and substance use among Mexican-American adolescents. J. Soc. Work Pract. Addict. 2010, 10, 283–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulis, S.; Marsiglia, F.F.; Ayers, S.L.; Booth, J.; Nuno-Gutierrez, B.L. Drug resistance and substance use among male and female adolescents in alternative secondary schools in Guanajuato, Mexico. J. Stud. Alcohol Drug. 2012, 73, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Dahl, S.L.; Sandberg, S. Female cannabis users and new masculinities: The gendering of cannabis use. Sociology 2015, 49, 696–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, R.J.; Johnson, J.L.; Carter, C.I.; Arora, K. “I couldn’t say, I’m not a girl”–adolescents talk about gender and marijuana use. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 68, 2029–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnull, E.; Ryder, J. ‘Because it’s fun’: English and American girls’ counter-hegemonic stories of alcohol and marijuana use. J. Youth Stud. 2019, 22, 1361–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hathaway, A.D.; Mostaghim, A.; Erickson, P.G.; Kolar, K.; Osborne, G. “It’s really no big deal”: The role of social supply networks in normalizing use of cannabis by students at Canadian universities. Deviant Behav. 2018, 39, 1672–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, C. A psychoactive paradox of masculinities: Cohesive and competitive relations between drug taking Irish men. Gend. Place Cult. 2019, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, C. ‘You’re with your ten closest mates… and everyone’s kind of in the same boat’: Friendship, masculinities and men’s recreational use of illicit drugs. J. Friendsh. Stud. 2018, 5, 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ilan, J. Street social capital in the liquid city. Ethnography 2012, 14, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, S.L. Remaining a user while cutting down: The relationship between cannabis use and identity. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2015, 22, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palamar, J.J.; Acosta, P.; Ompad, D.C.; Friedman, S.R. A qualitative investigation comparing psychosocial and physical sexual experiences related to alcohol and marijuana use among adults. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2018, 47, 757–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belackova, V.; Vaccaro, C.A. “A friend with weed is a friend indeed”: Understanding the relationship between friendship identity and market relations among marijuana users. J. Drug Issues 2013, 43, 289–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M. The role of anxiety in bisexual women’s use of cannabis in Canada. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2015, 2, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.; Sanches, M.; MacLeod, M.A. Prevalence and mental health correlates of illegal cannabis use among bisexual women. J. Bisex. 2016, 16, 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, C.A.; Gallego, J.D.; Bockting, W.O. Demographic characteristics, components of sexuality and gender, and minority stress and their associations to excessive alcohol, cannabis, and illicit (noncannabis) drug use among a large sample of transgender people in the United States. J. Prim. Prev. 2017, 38, 419–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hathaway, A.D.; Comeau, N.C.; Erickson, P.G. Cannabis normalization and stigma: Contemporary practices of moral regulation. Criminol. Crim. Justice 2011, 11, 451–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines-Saah, R.J.; Mitchell, S.; Slemon, A.; Jenkins, E.K. ‘Parents are the best prevention’? Troubling assumptions in cannabis policy and prevention discourses in the context of legalization in Canada. Int. J. Drug Policy 2019, 68, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.-Y.; Oliffe, J.L.; Bottorff, J.L.; Kelly, M.T. Masculinity and fatherhood: New fathers’ perceptions of their female partners’ efforts to assist them to reduce or quit smoking. Am. J. Men Health 2014, 9, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, A.; Iwamoto, D.K.; Grivel, M.; Clinton, L.; Brady, J. The role of feminine and masculine norms in college women’s alcohol use. Psychol. Men Masc. 2016, 17, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, S.; Williams, B.; Oliffe, J. The case for retaining a focus on “masculinities”. Int. J. Men Health 2016, 15, 52–67. [Google Scholar]

- Romo-Avilés, N.; Marcos-Marcos, J.; Tarragona-Camacho, A.; Gil-García, E.; Marquina-Márquez, A. “I like to be different from how i normally am”: Heavy alcohol consumption among female Spanish adolescents and the unsettling of traditional gender norms. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2018, 25, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Tang, L. Understanding women’s stories about drinking: Implications for health interventions. Health Educ. Res. 2018, 33, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triandafilidis, Z.; Ussher, J.M.; Perz, J.; Huppatz, K. Doing and undoing femininities: An intersectional analysis of young women’s smoking. Fem. Psychol. 2017, 27, 465–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, L. Can tobacco control be transformative? Reducing gender inequity and tobacco use among vulnerable populations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 792–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greaves, L. Smoke Screen: Women’s Smoking and Social Control; Scarlet Press: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, C.; Greaves, L.; Poole, N. Good, bad, thwarted or addicted? Discourses of substance-using mothers. Crit. Soc. Policy 2008, 28, 211–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettorre, E. Embodied deviance, gender, and epistemologies of ignorance: Re-visioning drugs use in a neurochemical, unjust world. Subst. Use Misuse 2015, 50, 794–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, N.C.Z.; Motz, M.; Pepler, D.J.; Jeong, J.J.; Khoury, J. Engaging mothers with substance use issues and their children in early intervention: Understanding use of service and outcomes. Child Abuse Neg. 2018, 83, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, L.; Oliffe, J.L.; Ponic, P.; Kelly, M.T.; Bottorff, J.L. Unclean fathers, responsible men: Smoking, stigma and fatherhood. Health Sociol. Rev. 2010, 19, 522–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottorff, J.L.; Oliffe, J.L.; Sarbit, G.; Kelly, M.T.; Cloherty, A. Men’s responses to online smoking cessation resources for new fathers: The influence of masculinities. Res. Protocol. 2015, 4, e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcomb, M.E.; Hill, R.; Buehler, K.; Ryan, D.T.; Whitton, S.W.; Mustanski, B. High burden of mental health problems, substance use, violence, and related psychosocial factors in transgender, non-binary, and gender diverse youth and young adults. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delahanty, J.; Ganz, O.; Hoffman, L.; Guillory, J.; Crankshaw, E.; Farrelly, M. Tobacco use among lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender young adults varies by sexual and gender identity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019, 201, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, A. Gender, reputation and regret: The ontological politics of Australian drug education. Gend. Educ. 2017, 29, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, L.; Pederson, A.; Poole, N. Making It Better: Gender Transformative Health Promotion; Canadian Scholars’ Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

| Author/Year | Country | Study Design | Study Aim | Population | Assessment of Cannabis Use | Dimension of Gender Addressed | Gender and Cannabis Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arnull and Ryder 2019 | UK and USA | qualitative comparative study | To prioritize the voices of justice-involved girls in the UK and USA regarding their reasons for substance use | age 13–18 adjudicated girls who had been sentenced for a violent offense; n = 24 girls in USA (primarily identified as “women of color”), n = 35 in UK (primarily White British) | Participants were assessed for eligibility based on self-reported “ever use” of cannabis and alcohol | Gender relations; explored use of alcohol and cannabis, within justice involved girls’ social groups. | Girls described pleasure related to their cannabis use with other girls. Within their friend groups they managed physical and sexual risks when using substances. |

| Belackova and Vaccaro 2013 | USA | qualitative | To explore the role of cannabis in friendship groups | n = 44 adult cannabis users and retailers in Florida; n = 32 men and n = 12 women; primarily White | Participants were assessed for eligibility based on self-reported use of cannabis in past 12 months | Gender relations in the context of reasons for/functions of cannabis use. | Some men described opportunities for pursuing intimate interactions with women when using cannabis. |

| Brady et al. 2016 | USA | systematic review | To examine feminine norms and substance use outcomes among women | only n = 2 studies included cannabis use (Kulis 2008; and Kulis 2010, see below) | Not reported | Gender norms; studies were eligible for inclusion if examined feminine norms/ideology or feminine role conflict. | Majority of studies reported that adherence to feminine norms increased substance use, but only two studies included cannabis (included below). |

| Dahl and Sandberg 2014 | Norway | qualitative | To examine how women navigate a gendered cannabis-use culture in Norway | Analyzed data from 2 studies: one with n = 100 cannabis using adults; and one with n = 25 experienced cannabis users (n = 7 women; n = 18 men) | Participants were assessed for eligibility based on self-reported long term cannabis use; included sporadic to heavy use (not quantified) | How adults “do gender” through cannabis use; examined women and men’s roles and positions in social networks using cannabis, and their concerns about use. | Dominant femininities and masculinities are both reinstated and reimagined through cannabis use. |

| Dahl 2015 | Norway | qualitative | To examine the change in identity among experienced cannabis users who had quit or reduced their use | n = 7 women, n = 18 men; Age = 23–40 years; former daily cannabis users who had reduced or quit using cannabis without formal drug and alcohol treatment | Participants were assessed for eligibility based on self-reported former daily cannabis use | Gender roles and gender relations in the context of reducing and quitting cannabis use. | New fathers discussed the cannabis user identity as incompatible with their role as father; men discussed changing their use in the context of intimate relationships. |

| Darcy 2019 | Ireland | qualitative | To explore how men’s illicit substance use patterns and intoxication converge with masculinities | n = 20 Irish men who used illicit substances (n = 17 heterosexual; 2 homosexual; 1 undeclared) | Participants identified as “recreational illicit drug users” | Gender relations; gender norms; applies a gender lens to examine Irish men’s illicit substance using practices in the context of masculinities, and within the context of use with other men. | Men use illicit substances as a way to navigate traditional masculinity in paradoxical ways: both for closeness in friendships, and in competition. |

| Darcy 2018 | Ireland | qualitative | To explore men’s substance use as a friendship practice | Same as above | Participants identified as “recreational illicit drug users” | Gender roles and relations; how cannabis is used in friendships and social settings, and in relation to conventional masculine stereotypes. | Cannabis use provided opportunities to “contravene conventional masculine stereotypes” (e.g., by offering a space for bonding with male friends, being more emotionally expressive), as well as reinforced masculine stereotypes (e.g., expressing dominance by obtaining and supplying substances, including cannabis). |

| Gonzalez, Gallego, and Bockting 2017 | USA | cross-sectional | To examine the relationship between gender minority stress and substance use among transgender adults | n = 1210 transgender adults (n = 680 transgender women; n = 530 transgender men) | Participants were asked: ‘‘In the last three months, how many days did you use marijuana or hashish (weed, grass, reefers)?’’ | Gender roles (non-conformity, gender minority stress), gender dysphoria and cannabis use. | Gender dysphoria was associated with cannabis use among both both transgender women and men; among transgender women, gender minority stress was associated with cannabis use. |

| Haines-Saah et al. 2019 | Canada | qualitative | To highlight the perspectives of parents on preventing problematic adolescent cannabis use, and critique notion of ‘parents as the best prevention’ | n = 16 parents of children (over age 13) who used cannabis; mostly women (n = 12) | Participants were eligible to participate if they were a parent of a child over age 13 who had experience with cannabis use | Discusses gender roles: expectations of mothers. | Mothers described feeling like failures if they had challenges regarding their child’s substance use, and experienced a lack of social support due to judgement and stigma. |

| Haines et al. 2009 | Canada | qualitative | To explore how adolescents perceive cannabis-use experiences as influenced by gender | n = 45 adolescents, 13–18 years; n = 26 boys, n = 19 girls | Participants included frequent cannabis users (minimum of past week use) | Gender norms, roles and relations; gender was coded into several sub-themes: styles of use by boys and girls; sex differences in use; gender and access; use in the context of relationships; issues of safety when smoking or ‘‘partying’’. Analysis focused on how students spoke about gender. | Girls and boys described gendered social dynamics in cannabis-use settings and patterns of use. |

| Hathaway et al. 2011 | Canada | qualitative | To examine extra- legal forms of stigma based on interviews with cannabis users | n = 92 (mean age 39) who had used cannabis on 25 or more occasions | Eligibility screening survey identified participants with personal experience with cannabis i (lifetime prevalence) | Gender roles; examines stigma in the context of cannabis use and the disadvantages and benefits of using. | Women described experiencing stigma when using cannabis during pregnancy and as mothers; conflict with the role of “good mother.” |

| Hathaway et al. 2018 | Canada | qualitative | To examine patterns of supply of cannabis among students at Canadian universities | n = 130 social sciences students in universities in Ontario and Alberta (55% female; 47% reported ever using cannabis) | Eligibility screening survey identified “regular” or “occasional” cannabis users (not quantified) | Gender relations in the context of cannabis supply. | Buying and maintaining a supply of cannabis was typically a male activity. |

| Ilan 2012 | Ireland | qualitative | To explore the experience of street culture among socio-economically disadvantaged young men in Ireland | n = 7 adolescents and young men engaged in street culture in Dublin | Not reported | Gender relations in the context of male friendships. | Cannabis was used to facilitate male friendships, social bonding. |

| Kulis et al. 2008 | Mexico | cross-sectional | To examine the relationship of femininity and masculinity constructs developed for Mexican-American youth with a range of substance use outcomes | n = 327 adolescents in Mexico | Self-report past 30 day use of cannabis (Likert scale) | Gender norms; assessed four constructs based on Mexican concepts of marianismo and machismo including: aggressive masculinity, assertive masculinity, affective femininity and submissive femininity. | Aggressive masculinity was associated with greater risk of substance use for most outcome measures, while affective femininity was generally associated with lower risks including less recent use of cannabis. |

| Kulis et al. 2010 | USA | cross-sectional | To examine the relationship of femininity and masculinity constructs with substance use among Mexican-American youth | n = 151 Mexican-American adolescents | Self-report past 30 day use of cannabis (Likert scale) | Same as Kulis et al. 2008. | Submissive femininity was significantly associated with alcohol use; no significant association was found for gender role and cannabis use. |

| Kulis et al. 2012 | USA | cross-sectional | To examine the relationship between adaptive and maladaptive constructs of masculinity and femininity, substance misuse and acculturation among Mexican-American youth | n = 1466 Mexican-American adolescents | Self-report past 30 day use of cannabis (Likert scale) | Same as Kulis et al. 2008. | Highly acculturated girls who reported high maladaptive masculinity (aggressive, controlling) reported the highest cannabis use. |

| Mahalik et al. 2015 | USA | cross sectional longitudinal | To examine the relationship between gender, male-typicality, and social norms on longitudinal patterns of alcohol intoxication and cannabis use in US youth | n = 10,588 youth (48% male; 52% female) | Self-report days per month cannabis use (Likert scale) | Gender norms; adherence to male typical behaviours and attitudes among females and males from adolescence to adulthood (based on measure of male typicality from Add Health data). | Greater male typicality among both females and males was associated with substance use including cannabis use; however, the effect was greater for males. |

| Palamar et al. 2018 | USA | qualitative | To examine and compare cannabis users’ psychosocial and physical sexual experiences and sexual risk behavior | n = 24 adults (n = 12 women; n = 12 men); all heterosexual | Participants were eligible to participate if they self-reported sexual intercourse while high on cannabis in the past 3 months | Gender relations; cannabis use in the context of heterosexual sexual relations. | Young women reported being more selective regarding sexual partners when they were using cannabis. Participants (female and male) reported feeling more in control on cannabis than alcohol, but also quieter and less social. |

| Robinson 2015 | Canada | mixed methods | To examine the impact of anxiety on cannabis use among bisexual women | n = 92 bisexual women ages 18–54 | Self- report cannabis use in the past year (Likert scale) using the Drug Use Disorders Identification Test-Extended Version (DUDIT- E) | Non-conformity to gender roles and impact on stress and substance use. | Cannabis may be used as a way to cope with “female gender roles”, and discrimination based on gender and sexual orientation. |

| Robinson, Sanches, and MacLeod 2016 | Canada | correlational | To examine the prevalence and mental health correlates of illicit cannabis use among bisexual women | n = 262 bisexual adult women | Self- report cannabis use in the past year (Likert scale) using the Drug Use Disorders Identification Test-Extended Version (DUDIT- E) | Gender relations; non conformity to gender roles and social exclusion. | Cannabis use correlated with social support; bisexual women who often face social exclusion may use cannabis as a tool for social connection. |

| Wilkinson et al. 2018 | USA | cross- sectional longitudinal | To examine the associations between adherence to gender-typical behavior and substance use from adolescence to adulthood | n = 4617 males; n = 5660 females | Self-report number of occurrences (Waves 1 and 3) and days of cannabis use (Wave 4) in the past 30 days | Gender norms; gender typicality based on adherence to gender typical behaviours; behaviours included a range from individual actions (e.g., exercising) to states of being (e.g., getting sad) that correlated with being female or male. | Greater male typicality at wave one was associated with greater odds of high frequency cannabis and cigarette use and increased risk of use of one or more substances at Wave three (during emerging adulthood). Among females, there was a lower change in high frequency use and polysubstance use over time. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hemsing, N.; Greaves, L. Gender Norms, Roles and Relations and Cannabis-Use Patterns: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 947. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030947

Hemsing N, Greaves L. Gender Norms, Roles and Relations and Cannabis-Use Patterns: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(3):947. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030947

Chicago/Turabian StyleHemsing, Natalie, and Lorraine Greaves. 2020. "Gender Norms, Roles and Relations and Cannabis-Use Patterns: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 3: 947. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030947

APA StyleHemsing, N., & Greaves, L. (2020). Gender Norms, Roles and Relations and Cannabis-Use Patterns: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 947. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030947