Problematic Internet Use, Non-Medical Use of Prescription Drugs, and Depressive Symptoms among Adolescents: A Large-Scale Study in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, M.P.; Wu, J.Y.; Chen, C.J.; You, J. Positive outcome expectancy mediates the relationship between social influence and Internet addiction among senior high-school students. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, J.; Sun, Y.; Wan, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Tao, F. Associations between problematic internet use and adolescents’ physical and psychological symptoms: Possible role of sleep quality. J. Addict. Med. 2014, 8, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rucker, J.; Akre, C.; Berchtold, A.; Suris, J.C. Problematic Internet use is associated with substance use in young adolescents. Acta Paediatr. 2015, 104, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Gaming Disoder. Available online: https://www.who.int/features/qa/gaming-disorder/en/ (accessed on 8 December 2019).

- Tymula, A.; Rosenberg, B.L.; Roy, A.K.; Ruderman, L.; Manson, K.; Glimcher, P.W.; Levy, I. Adolescents’ risk-taking behavior is driven by tolerance to ambiguity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 17135–17140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Public Health Implications of Excessive Use of the Internet, Computers, Smartphones and Similar Electronic Devices Meeting report. In Main Meeting Hall, Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research National Cancer Research Centre; World Health Organization: Tokyo, Japan, 2015.

- Thapar, A.; Collishaw, S.; Pine, D.S.; Thapar, A.K. Depression in adolescence. Lancet 2012, 379, 1056–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesselhoeft, R.; Sorensen, M.J.; Heiervang, E.R.; Bilenberg, N. Subthreshold depression in children and adolescents—A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 151, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Deng, J.; He, Y.; Deng, X.; Huang, J.; Huang, G.; Gao, X.; Lu, C. Prevalence and correlates of sleep disturbance and depressive symptoms among Chinese adolescents: A cross-sectional survey study. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e5517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Hong, K.E.; Park, E.J.; Ha, K.S.; Yoo, H.J. The association between problematic internet use and depression, suicidal ideation and bipolar disorder symptoms in Korean adolescents. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2013, 47, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lu, Y.; Li, L. Exploring Associations between Problematic Internet Use, Depressive Symptoms and Sleep Disturbance among Southern Chinese Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeClair, A.; Kelly, B.C.; Pawson, M.; Wells, B.E.; Parsons, J.T. Motivations for Prescription Drug Misuse among Young Adults: Considering Social and Developmental Contexts. Drugs 2015, 22, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Behavioral Health Trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 15-4927, NSDUH Series H-50); Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.; Luo, M.; Wang, W.; Xiao, D.; Xi, C.; Wang, T.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, W.H.; Lu, C. Association between nonmedical use of opioids or sedatives and suicidal behavior among Chinese adolescents: An analysis of sex differences. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2019, 53, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, D.H.; Hwang, J.W.; Renshaw, P.F. Bupropion sustained release treatment decreases craving for video games and cue-induced brain activity in patients with Internet video game addiction. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2010, 18, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, M.; Young, K.S.; Laier, C. Prefrontal control and internet addiction: A theoretical model and review of neuropsychological and neuroimaging findings. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quello, S.B.; Brady, K.T.; Sonne, S.C. Mood disorders and substance use disorder: A complex comorbidity. Sci. Pract. Perspect. 2005, 3, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caplan, S.E. Theory and measurement of generalized problematic Internet use: A two-step approach. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.A.; Flett, G.L.; Besser, A. Validation of a new scale for measuring problematic internet use: Implications for pre-employment screening. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2002, 5, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.A. A cognitive-behavioral model of pathological Internet use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2001, 17, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Luo, M.; Wang, W.X.; Huang, G.L.; Xu, Y.; Gao, X.; Lu, C.Y.; Zhang, W.H. Association between problematic Internet use, sleep disturbance, and suicidal behavior in Chinese adolescents. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 965–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crockett, L.J.; Beal, S.J. The life course in the making: Gender and the development of adolescents’ expected timing of adult role transitions. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 48, 1727–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramo, D.E.; Liu, H.; Prochaska, J.J. Reliability and validity of young adults’ anonymous online reports of marijuana use and thoughts about use. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2012, 26, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Stewart, S.M.; Byrne, B.M.; Wong, J.P.; Ho, S.Y.; Lee, P.W.; Lam, T.H. Factor structure of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale in Hong Kong adolescents. J. Pers. Assess 2008, 90, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radloff, L.S. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. J. Youth Adolesc. 1991, 20, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Xu, Y.; Deng, J.; Huang, J.; Huang, G.; Gao, X.; Wu, H.; Pan, S.; Zhang, W.H.; Lu, C. Association Between Nonmedical Use of Prescription Drugs and Suicidal Behavior Among Adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.J.; Soong, W.T.; Kuo, P.H.; Chang, H.L.; Chen, W.J. Using the CES-D in a two-phase survey for depressive disorders among nonreferred adolescents in Taipei: A stratum-specific likelihood ratio analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2004, 82, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, C.M.; Mak, K.K.; Watanabe, H.; Ang, R.P.; Pang, J.S.; Ho, R.C. Psychometric properties of the internet addiction test in Chinese adolescents. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2013, 38, 794–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zhou, X.; Lu, C.; Wu, J.; Deng, X.; Hong, L. Problematic Internet Use in high school students in Guangdong Province, China. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, K.S. Caught in the Net: How to Recognize the Signs of Internet Addiction and a Winning Strategy for Recovery; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Evaluating Model Fit; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Garver, M.S.; Mentzer, J.T. Logistics research methods: Employing structural equation modeling to test for construct validity. J. Bus Logist 1999, 20, 33–57. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X.; Tang, S.; Ren, Z.; Wong, D. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among adolescents in secondary school in mainland China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 245, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, S.; Yau, Y.H.; Chai, J.; Guo, J.; Potenza, M.N. Problematic Internet use, well-being, self-esteem and self-control: Data from a high-school survey in China. Addict. Behav. 2016, 61, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, R.C.; Zhang, M.W.; Tsang, T.Y.; Toh, A.H.; Pan, F.; Lu, Y.; Cheng, C.; Yip, P.S.; Lam, L.T.; Lai, C.M.; et al. The association between internet addiction and psychiatric co-morbidity: A meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalbudak, E.; Evren, C.; Aldemir, S.; Coskun, K.S.; Ugurlu, H.; Yildirim, F.G. Relationship of internet addiction severity with depression, anxiety, and alexithymia, temperament and character in university students. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2013, 16, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, R.D.; Farrahi, L.; Glazier, S.; Sussman, S.; Leventhal, A.M. Depressive symptoms, negative urgency and substance use initiation in adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014, 144, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, B.J.; Getz, S.; Galvan, A. The adolescent brain. Dev. Rev. 2008, 28, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindley, P.; Walker, S.N. Theoretical and methodological differentiation of moderation and mediation. Nurs. Res. 1993, 42, 276–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, Y.H.; Potenza, M.N.; White, M.A. Problematic Internet Use, Mental Health and Impulse Control in an Online Survey of Adults. J. Behav. Addict. 2013, 2, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khantzian, E.J. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 1997, 4, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Han, D.H.; Kim, S.M.; Renshaw, P.F. Substance abuse precedes Internet addiction. Addict. Behav. 2013, 38, 2022–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total | CES-D Scores, Mean (SD) | p-Value * | Depressive Symptoms | p-Value * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||

| Total | 24,345 (100) | 13.6 (8.7) | 1631 (6.7) | 22,714 (93.3) | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Boys | 12,526 (51.5) | 12.9 (8.6) | <0.001 | 731 (45.0) | 11,795 (52.1) | <0.001 |

| Girls | 11,732 (48.2) | 14.4 (8.8) | 892 (55.0) | 10,840 (47.9) | ||

| Missing data | 87 (0.4) | |||||

| Living arrangement | ||||||

| Living in two-parent family | 18,094 (74.3) | 13.3 (8.6) | <0.001 | 1125 (69.1) | 16,969 (74.9) | <0.001 |

| Living in a single-parent family | 2905 (11.9) | 15.0 (9.4) | 259 (15.9) | 2646 (11.7) | ||

| Living with others | 3281 (13.5) | 14.3 (8.8) | 243 (14.9) | 3038 (13.4) | ||

| Missing data | 65 (0.3) | |||||

| HSS | ||||||

| Above average | 6942 (28.5) | 12.1 (8.1) | <0.001 | 315 (19.3) | 6627 (29.3) | <0.001 |

| Average | 13,944 (57.3) | 13.8 (8.6) | 928 (57.0) | 13,016 (57.5) | ||

| Below average | 3388 (13.9) | 16.3 (9.8) | 385 (23.6) | 3003 (13.3) | ||

| Missing data | 71 (0.3) | |||||

| Academic performance | ||||||

| Above average | 9195 (37.8) | 12.3 (8.5)) | <0.001 | 508 (31.2) | 8687 (38.5) | <0.001 |

| Average | 7576 (31.1) | 13.5 (8.2) | 434 (26.7) | 7142 (31.6) | ||

| Below average | 7448 (30.6) | 15.5 (9.3) | 685 (42.1) | 6763 (29.9) | ||

| Missing data | 126 (0.5) | |||||

| Family relationships | ||||||

| Good | 19,899 (81.7) | 12.6 (8.0) | <0.001 | 946 (58.1) | 18,953 (83.8) | <0.001 |

| Average | 3362 (13.8) | 17.6 (9.8) | 429 (26.3) | 2933 (13.0) | ||

| Poor | 986 (4.1) | 21.5 (11.9) | 254 (15.6) | 732 (3.2) | ||

| Missing data | 98 (0.4) | |||||

| Classmate relations | ||||||

| Good | 19,561 (80.3) | 12.5 (7.9) | <0.001 | 899 (55.3) | 18,662 (82.6) | <0.001 |

| Average | 4274 (17.6) | 17.9 (9.7) | 580 (35.7) | 3694 (16.4) | ||

| Poor | 381 (1.6) | 26.3 (13.7) | 146 (9.0) | 235 (1.0) | ||

| Missing data | 129 (0.5) | |||||

| Relationship with teachers | ||||||

| Good | 15,695 (64.5) | 12.1 (7.9) | <0.001 | 706 (43.6) | 14,989 (66.6) | <0.001 |

| Average | 7844 (32.2) | 16.2 (9.2) | 790 (48.8) | 7054 (31.4) | ||

| Poor | 576 (2.4) | 21.2 (12.6) | 124 (7.7) | 452 (2.0) | ||

| Missing data | 230 (0.9) | |||||

| IAT scores, Mean (SD) | 35.8 (12.8) | NA | 49.3 (16.5) | 34.8 (11.9) | <0.001 | |

| Opioid misuse | ||||||

| Abstainers | 23,822 (97.9) | 13.6 (8.7) | <0.001 | 1559 (95.6) | 22,263 (98.0) | <0.001 |

| Experimenters | 384 (1.6) | 17.3 (10.0) | 49 (3.0) | 335 (1.5) | ||

| Frequent users | 139 (0.6) | 19.2 (9.8) | 23 (1.4) | 116 (0.5) | ||

| Sedative misuse | ||||||

| Abstainers | 24,095 (99.0) | 13.6 (8.7) | <0.001 | 1588 (97.4) | 22,507 (99.1) | <0.001 |

| Experimenters | 188 (0.8) | 17.4 (9.1) | 23 (1.4) | 165 (0.7) | ||

| Frequent users | 62 (0.3) | 23.8 (14.6) | 20 (1.2) | 42 (0.2) | ||

| Variable | CES-D scores | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

| β Estimate # (95% CI) | p-Value | β Estimate # (95% CI) | p-Value | β Estimate # (95% CI) | p-Value | β Estimate # (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Problematic Internet use (1-score increase) | 0.30 (0.29–0.31) | <0.001 | 0.26 (0.25–0.27) | <0.001 | 0.26 (0.25–0.27) | <0.001 | 0.26 (0.25–0.27) | <0.001 |

| Opioid misuse (Ref. = Abstainers) | ||||||||

| Experimenters | 3.75 (2.82–4.68) | <0.001 | 2.77 (1.90–3.63) | <0.001 | 2.42 (0.19–4.65) | 0.034 | NA | |

| Frequent users | 5.65 (4.11–7.12) | <0.001 | 4.45 (3.02–5.88) | <0.001 | 3.95(−0.32–8.22) | 0.071 | NA | |

| Sedative misuse (Ref.= Abstainers) | ||||||||

| Experimenters | 3.85 (2.54–5.17) | <0.001 | 2.86 (1.63–4.09) | <0.001 | NA | 2.53 (−0.86–5.91) | 0.144 | |

| Frequent users | 10.26 (8.03–12.48) | <0.001 | 7.18 (5.09–9.26) | <0.001 | NA | 10.85 (5.15–16.56) | <0.001 | |

| Interaction item (opioid misuse) | ||||||||

| Experimenters * Problematic Internet use | NA | NA | −0.02 (−0.07–0.03) | 0.502 | NA | |||

| Frequent users * Problematic Internet use | NA | NA | −0.04 (−0.13–0.05) | 0.387 | NA | |||

| Interaction item (sedative misuse) | ||||||||

| Experimenters * Problematic Internet use | NA | NA | NA | −0.01 (−0.09–0.08) | 0.884 | |||

| Frequent users * Problematic Internet use | NA | NA | NA | −0.11 (−0.22–0.01) | 0.086 | |||

| Variable. | Symbol | CES-D Scores | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Model | Adjusted Model * | ||

| Standardized β Estimate (95% CI) | Standardized β Estimate (95% CI) | ||

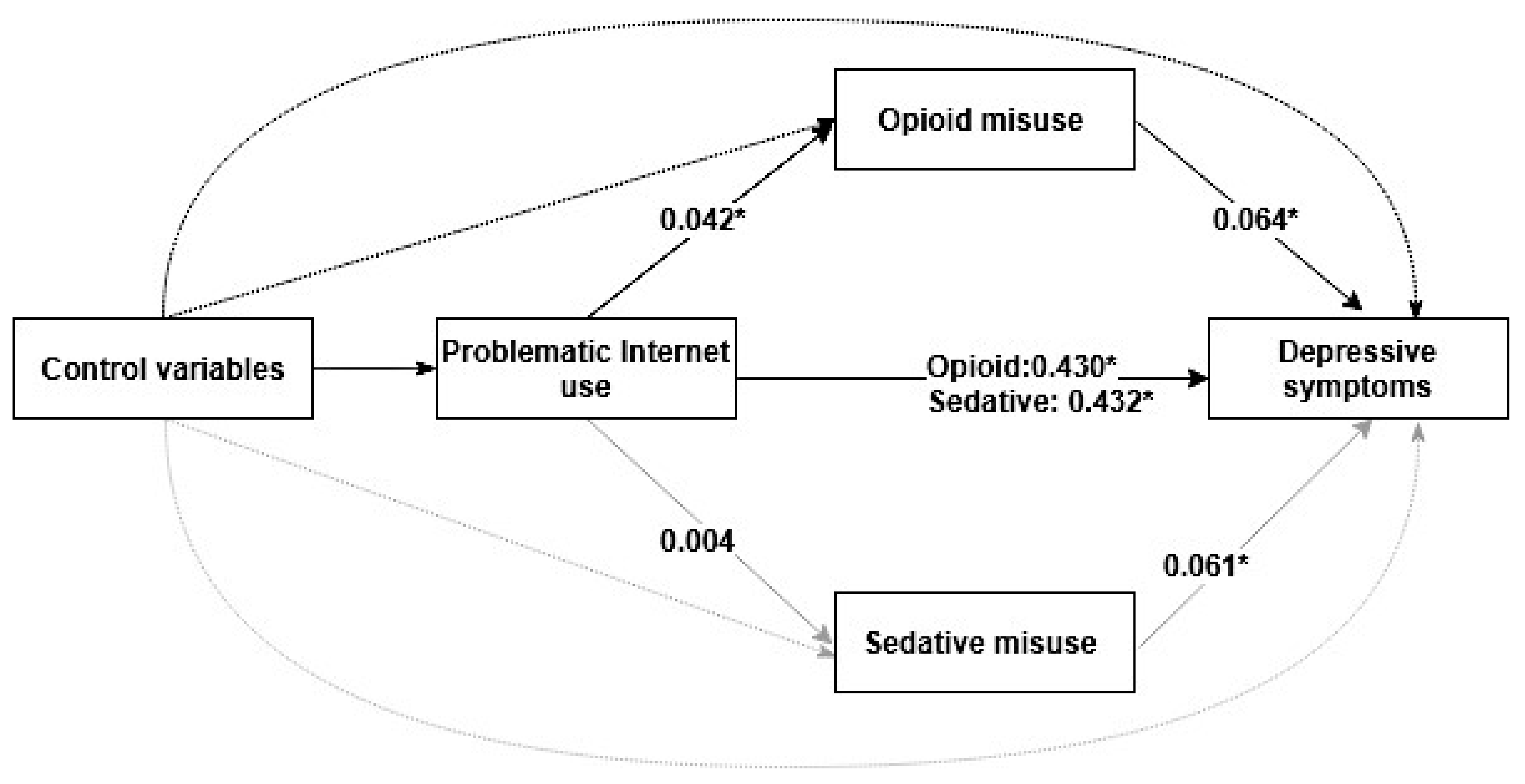

| Problematic Internet use » Depressive symptoms | Predictor » Outcome | 0.437 (0.425–0.449) | 0.430 (0.418–0.442) |

| Opioid misuse » Depressive symptoms | Mediator » Outcome | 0.072 (0.058–0.086) | 0.064 (0.048–0.080) |

| Problematic internet use » Opioid misuse | Predictor » Mediator | 0.045 (0.033–0.057) | 0.042 (0.030–0.054) |

| Standardized effect | |||

| Indirect | 0.003 (0.001–0.005) | 0.003 (0.001–0.005) | |

| Total | 0.441 (0.429–0.453) | 0.430 (0.418–0.442) | |

| Problematic Internet use » Depressive symptoms | Predictor » Outcome | 0.4395 (0.4280–0.4518) | 0.4318 (0.4202–0.4439) |

| Sedative misuse » Depressive symptoms | Mediator » Outcome | 0.072 (0.058–0.086) | 0.061 (0.045–0.077) |

| Problematic internet use » Sedative misuse | Predictor » Mediator | 0.007 (−0.005–0.019) | 0.004 (−0.008–0.016) |

| Standardized effect | |||

| Indirect | 0.0005 (−0.002–0.0006) | 0.0002 (−0.0018–0.0003) | |

| Total | 0.440 (0.428–0.452) | 0.432 (0.420–0.444) | |

| Variable | Symbol | Problematic Internet Use | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Model | Adjusted Model * | ||

| Standardized β Estimate (95% CI) | Standardized β Estimate (95% CI) | ||

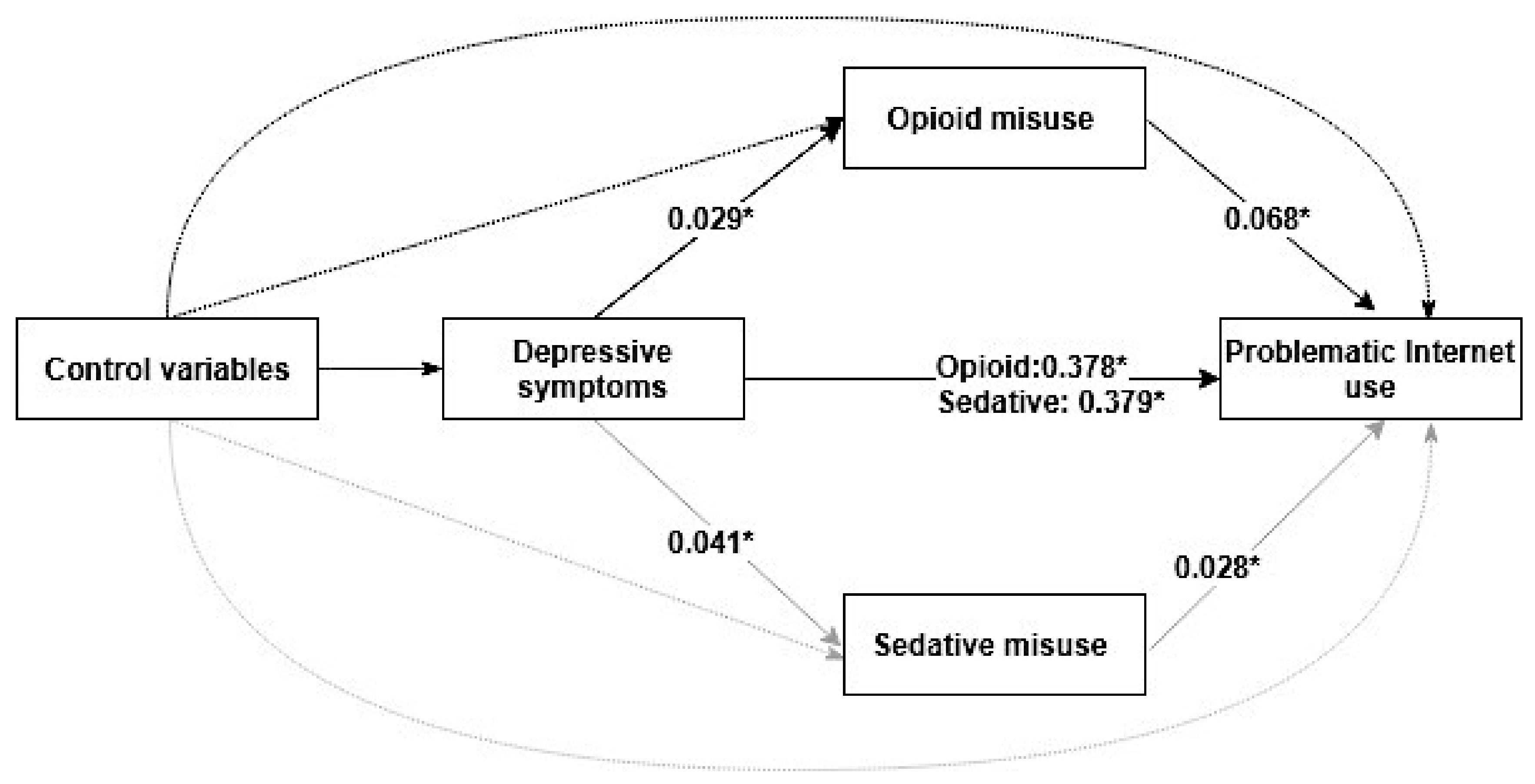

| CES-D scores » Problematic Internet use | Predictor » Outcome | 0.438 (0.426–0.450) | 0.378 (0.366–0.390) |

| Opioid misuse » Problematic Internet use | Mediator » Outcome | 0.076 (0.062–0.090) | 0.068 (0.054–0.082) |

| CES-D scores » Opioid misuse | Predictor » Mediator | 0.038 (0.026–0.050) | 0.029 (0.017–0.041) |

| Standardized effect | |||

| Indirect | 0.003 (0.001–0.005) | 0.002 (0.001–0.002) | |

| Total | 0.441 (0.429–0.453) | 0.380 (0.368–0.392) | |

| CES-D scores » Problematic Internet use | Predictor » Outcome | 0.438 (0.426–0.450) | 0.379 (0.367–0.391) |

| Sedative misuse » Problematic Internet use | Mediator » Outcome | 0.039 (0.025–0.053) | 0.028 (0.014–0.042) |

| CES-D scores » Sedative misuse | Predictor » Mediator | 0.056 (0.044–0.068) | 0.041 (0.029–0.053) |

| Standardized effect | |||

| Indirect | 0.002 (0.001–0.002) | 0.001 (0.001–0.001) | |

| Total | 0.440 (0.429–0.453) | 0.380 (0.368–0.392) | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fan, B.; Wang, W.; Wang, T.; Xie, B.; Zhang, H.; Liao, Y.; Lu, C.; Guo, L. Problematic Internet Use, Non-Medical Use of Prescription Drugs, and Depressive Symptoms among Adolescents: A Large-Scale Study in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 774. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030774

Fan B, Wang W, Wang T, Xie B, Zhang H, Liao Y, Lu C, Guo L. Problematic Internet Use, Non-Medical Use of Prescription Drugs, and Depressive Symptoms among Adolescents: A Large-Scale Study in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(3):774. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030774

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Beifang, Wanxing Wang, Tian Wang, Bo Xie, Huimin Zhang, Yuhua Liao, Ciyong Lu, and Lan Guo. 2020. "Problematic Internet Use, Non-Medical Use of Prescription Drugs, and Depressive Symptoms among Adolescents: A Large-Scale Study in China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 3: 774. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030774

APA StyleFan, B., Wang, W., Wang, T., Xie, B., Zhang, H., Liao, Y., Lu, C., & Guo, L. (2020). Problematic Internet Use, Non-Medical Use of Prescription Drugs, and Depressive Symptoms among Adolescents: A Large-Scale Study in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 774. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030774