Experience of Stress Assessed by Text Messages and Its Association with Objective Workload—A Longitudinal Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

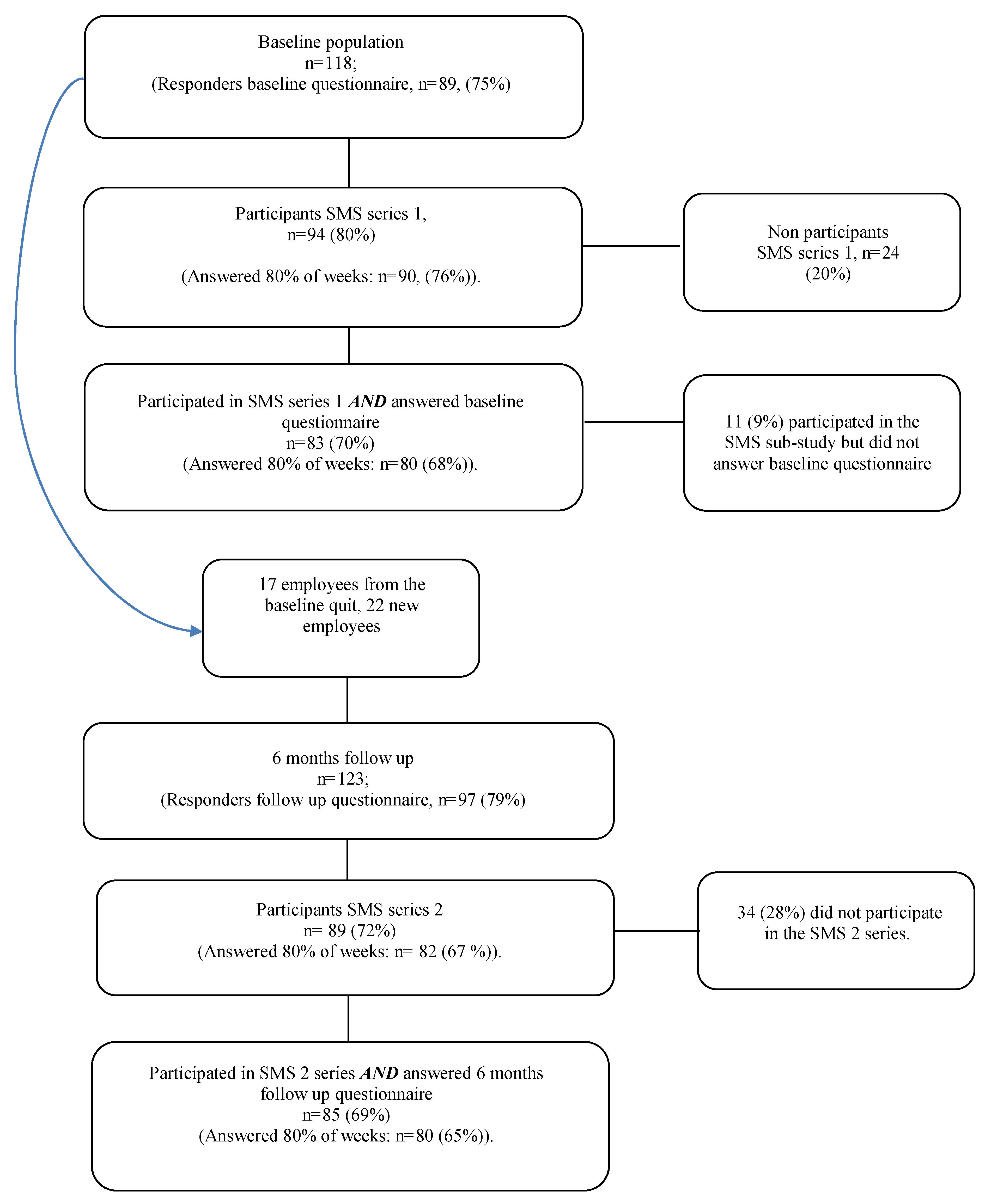

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Stress

2.2.2. Exhaustion

2.2.3. Depression

2.2.4. Over-Commitment

2.2.5. Objective Organizational Measures of Quantitative Workload

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.3.1. The Analysis Pertaining to the First Aim: To Examine and Describe the Experience of Stress Over Time in a Group of Swedish Primary Health Care Employees

2.3.2. The Analysis Pertaining to the Second aim: The Associations between the Experience of Stress and the Group-Level Objective Organizational Measures of Quantitative Workload

2.3.3. The Analysis Pertaining to the Third Aim: To Describe the Intra-Individual Variability (i.e., Patterns of Fluctuation) in the Experience of Stress

- (A)

- We are not aware of any previous studies that have identified cut off scores for high and low stress subgroups based on a time series. Therefore, we first computed means (M) and standard deviations (SD) of all the stress scores for all participants in the SMS series 1 and SMS series 2 separately. Based on the frequency tables of these means and standard deviations, we selected four stress sub-groups: LL (low M/low SD), LH (low M/high SD), HL (high M/low SD), and HH (high M/high SD). When we chose the upper quartile as cut off for dichotomization, only a few persons fell into the HH group. We therefore chose the upper tertile for dichotomization of high/low to obtain more individuals in the HH group. Table 1 displays the means and the standard deviations used in the formation of these sub-groups.

- (B)

- Secondly, the intra-individual variability was calculated by the ordering of observations. For some individuals, high and low scores can follow each other in quick succession. The speed of change can be described by calculating so-called first difference (called first derivative in [48]). In other words, some individuals do not change much between two occasions while others have rapid increases or decreases in scores [48]. The first difference is the value of the measurement at a time t minus the value of the measurement at the previous time. The four subgroups were formed as described under A), but with the cut off for the SD of the first difference = 1.115 for SMS series 1 and SD = 1.098 for the SMS series 2.

3. Results

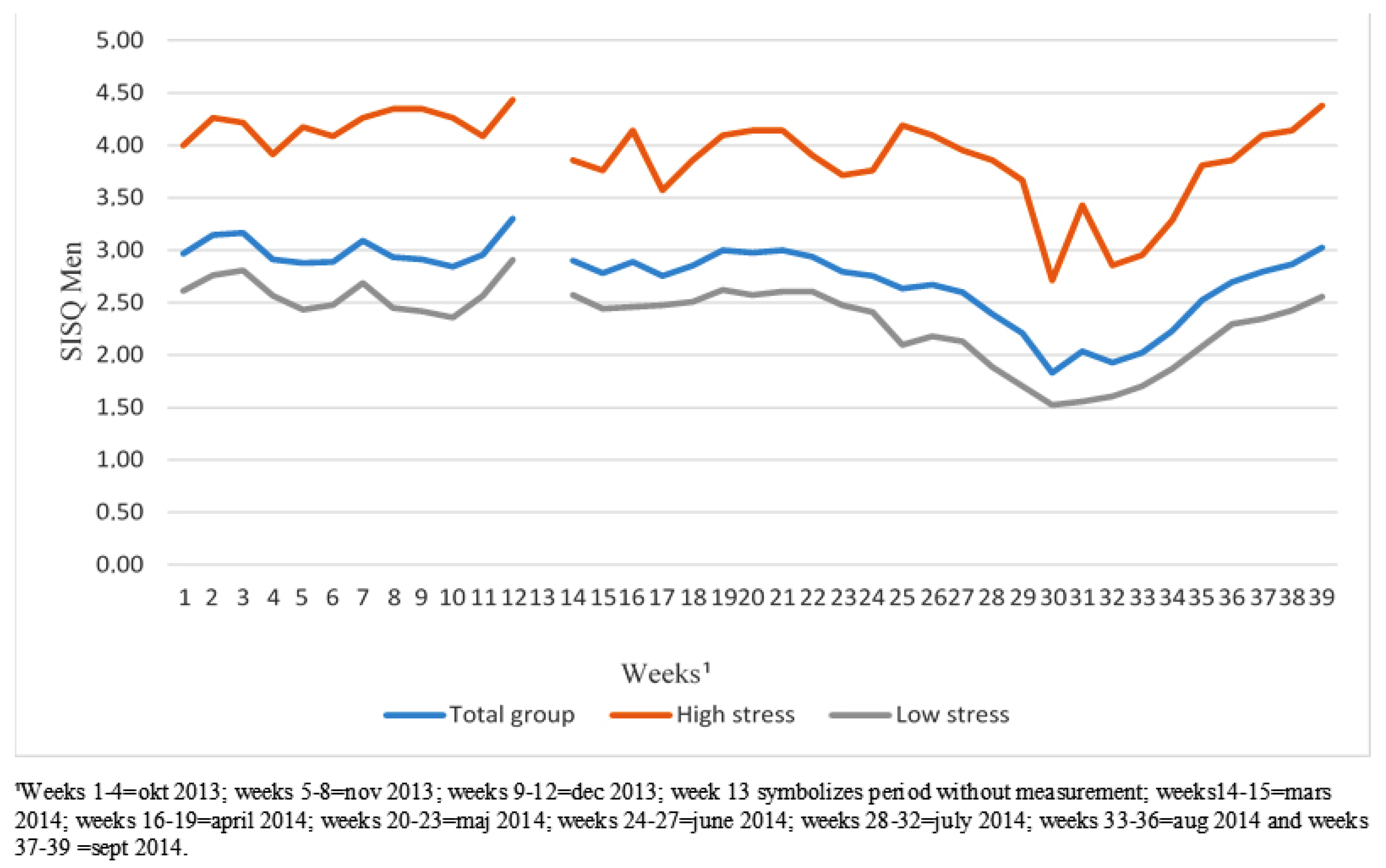

3.1. The Experience of StressOver Time

3.2. The Experience of Stress and the Objective Measures of Quantitative Workload

3.3. The Intra-Individual Variability

4. Discussion

4.1. The Experience of StressOver Time

4.2. The Experience of Stress and the Objective Measures of Quantitative Workload

4.3. The Intra-Individual Variability

4.4. Methodological Considerations

5. Conclusions and Implication for Practice

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| SMS 1 Series | |||

| Week | (a) Total Group N = 90 | (b) High Stress Sub-Group ¹, N = 23 | (b) Low Stress Sub-Group ¹, N = 67 |

| 1 | 2.97 (1.2) | 4.00 (1.0) | 2.61 (1.1) |

| 2 | 3.14 (1.3) | 4.26 (0.9) | 2.76 (1.3) |

| 3 | 3.17 (1.4) | 4.22 (0.9) | 2.81 (1.3) |

| 4 | 2.91 (1.3) | 3.91 (0.8) | 2.57 (1.3) |

| 5 | 2.88 (1.2) | 4.17 (0.7) | 2.43 (1.1) |

| 6 | 2.89 (1.2) | 4.09 (0.8) | 2.48 (1.1) |

| 7 | 3.09 (1.2) | 4.26 (0.8) | 2.69 (1.1) |

| 8 | 2.93 (1.3) | 4.35 (0.5) | 2.45 (1.0) |

| 9 | 2.91 (1.3) | 4.35 (0.8) | 2.42 (1.1) |

| 10 | 2.84 (1.3) | 4.26 (0.7) | 2.36 (1.0) |

| 11 | 2.96 (1.3) | 4.09 (0.8) | 2.57 (1.2) |

| 12 | 3.30 (1.3) | 4.43 (0.6) | 2.91 (1.2) |

| SMS 2 Series | |||

| Week | Total Group N = 82 | High Stress Sub-Group ², N = 21 | Low Stress Sub-Group ², N = 61 |

| 1 | 2.90 (1.3) | 3.86 (1.2) | 2.57 (1.1) |

| 2 | 2.78 (1.2) | 3.76 (1.0) | 2.44 (1.1) |

| 3 | 2.89 (1.3) | 4.14 (1.0) | 2.46 (1.1) |

| 4 | 2.76 (1.3) | 3.57 (1.2) | 2.48 (1.2) |

| 5 | 2.85 (1.2) | 3.86 (1.1) | 2.51 (1.1) |

| 6 | 3.00 (1.3) | 4.10 (1.0) | 2.62 (1.1) |

| 7 | 2.98 (1.2) | 4.14 (1.1) | 2.57 (1.0) |

| 8 | 3.00 (1.2) | 4.14 (1.0) | 2.61 (1.1) |

| 9 | 2.94 (1.3) | 3.90 (0.9) | 2.61 (1.2) |

| 10 | 2.79 (1.2) | 3.71 (1.1) | 2.48 (1.0) |

| 11 | 2.76 (1.2) | 3.76 (1.3) | 2.41 (1.0) |

| 12 | 2.63 (1.3) | 4.19 (0.9) | 2.10 (0.9) |

| 13 | 2.67 (1.3) | 4.10 (1.0) | 2.18 (1.0) |

| 14 | 2.60 (1.4) | 3.95 (1.3) | 2.13 (1.1) |

| 15 | 2.39 (1.4) | 3.86 (1.2) | 1.89 (1.0) |

| 16 | 2.21 (1.4) | 3.67 (1.3) | 1.70 (1.1) |

| 17 | 1.83 (1.2) | 2.71 (1.4) | 1.52 (0.9) |

| 18 | 2.04 (1.3) | 3.43 (1.5) | 1.56 (0.8) |

| 19 | 1.93 ( 1.2) | 2.86 (1.3) | 1.61 (1.0) |

| 20 | 2.02 (1.2) | 2.95 (1.3) | 1.70 (0.9) |

| 21 | 2.23 (1.2) | 3.29 (1.3) | 1.87 (0.9) |

| 22 | 2.52 (1.3) | 3.81 (0.9) | 2.08 (1.1) |

| 23 | 2.70 (1.3) | 3.86 (0.9) | 2.30 (1.1) |

| 24 | 2.79 (1.3) | 4.10 (0.8) | 2.34 (1.2) |

| 25 | 2.87 (1.4) | 4.14 (0.9) | 2.43 (1.3) |

| 26 | 3.02 (1.4) | 4.38 (0.7) | 2.56 (1.2) |

References

- Quick, J.C.; Henderson, D.F. Occupational Stress: Preventing Suffering, Enhancing Wellbeing. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassard, J.; Teoh, K.; Cox, T.; Dewe, P.; Cosmar, M.; Gründler, R.; Flemming, D.; Cosemans, B.; Van den Broek, K. Calculating the Costs of Work-Related Stress and Psychosocial Risks—A Literature Review; European Agency for Safety and Health at Work: Bilbao, Spain; European Risk Observatory: Luxembourg; Publications Office of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2014; pp. 1831–9351. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Kessler, R.C.; Gordon, L.U. Measuring Stress: A Guide for Health and Social Scientists; Oxford University Press, USA: Cary, NC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Berntson, E.; Bernhard-Oettel, C.; Hellgren, J.; Näswall, K.; Sverke, M. Enkätmetodik (Survey methodology), 1st ed.; Natur & Kultur: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gurolurganci, I.; de Jongh, T.; Vodopivecjamsek, V.; Car, J.; Atun, R. Mobile phone messaging for communicating results of medical investigations. Cochrane Consum. Commun. Group 2012, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodopivecjamsek, V.; de Jongh, T.; Gurolurganci, I.; Atun, R.; Car, J. Mobile phone messaging for preventive health care. Cochrane Consum. Commun. Group 2012, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axén, I.; Bodin, L.; Kongsted, A.; Wedderkopp, N.; Jensen, I.; Bergstrom, G. Analyzing repeated data collected by mobile phones and frequent text messages. An example of low back pain measured weekly for 18 weeks. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2012, 12, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axén, I.; Bodin, L.; Bergstrom, G.; Halasz, L.; Lange, F.; Lovgren, P.W.; Rosenbaum, A.; Leboeuf-Yde, C.; Jensen, I. The use of weekly text messaging over 6 months was a feasible method for monitoring the clinical course of low back pain in patients seeking chiropractic care. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2012, 65, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, B.; Wedderkopp, N. Comparison between data obtained through real-time data capture by SMS and a retrospective telephone interview. Chiropr. Osteopathy 2010, 18, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, M.O.; Krantz, M.J.; Albright, K.; Beaty, B.; Coronel-Mockler, S.; Bull, S.; Estacio, R.O. A controlled trial of mobile short message service among participants in a rural cardiovascular disease prevention program. Prev. Med. Rep. 2019, 13, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, S.; Nemser, B.; Cole-Lewis, H.; Kaonga, N.; Negin, J.; Namakula, P.; Ohemeng-Dapaah, S.; Kanter, A.S. Effectiveness of SMS Technology on Timely Community Health Worker Follow-Up for Childhood Malnutrition: A Retrospective Cohort Study in sub-Saharan Africa. Glob. Health Sci. Pr. 2018, 6, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Þórarinsdóttir, H.; Kessing, L.; Faurholt-Jepsen, M. Smartphone-Based Self-Assessment of Stress in Healthy Adult Individuals: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Ceja, E.; Osmani, V.; Mayora, O. Automatic Stress Detection in Working Environments From Smartphones’ Accelerometer Data: A First Step. Biomed. Health Inform. IEEE J. 2016, 20, 1053–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muaremi, A.; Arnrich, B.; Tröster, G. Towards Measuring Stress with Smartphones and Wearable Devices During Workday and Sleep. BioNanoScience 2013, 3, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ursin, H.; Eriksen, H.R. Cognitive activation theory of stress (CATS). Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2010, 34, 877–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbetsmiljöverket. The Work Environment 2015; Swedish Work Environment Authority: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Arbetsmiljöverket. The Work Environment 2017; Swedish Work Environment Authority: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Häusser, J.A.; Mojzisch, A.; Niesel, M.; Schulz-hardt, S. Ten years on: A review of recent research on the Job Demand–Control (-Support) model and psychological well-being. Work Stress 2010, 24, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.; Nielsen, M.B.; Ogbonnaya, C.; Känsälä, M.; Saari, E.; Isaksson, K. Workplace resources to improve both employee well-being and performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Work Stress 2017, 31, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirom, A.; Nirel, N.; Vinokur, A.D. Physician Burnout as Predicted by Subjective and Objective Workload and by Autonomy. In Handbook of Stress and Burnout in Health Care; Halbesleben, J.R.B., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers, Incorporated: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ganster, D.; Rosen, C.; Fisher, G. Long Working Hours and Well-being: What We Know, What We Do Not Know, and What We Need to Know. J. Bus. Psychol. 2018, 33, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, S.E. The web of silence: A qualitative case study of early intervention and support for healthcare workers with mental ill-health. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindek, S.; Spector, P.E. Organizational constraints: A meta-analysis of a major stressor. Work Stress 2016, 30, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayon, P.; Bass, E.J.; Bellandi, T.; Gurses, A.P.; Hallbeck, M.S.; Mollo, V. Sociotechnical systems analysis in health care: A research agenda. IIE Trans. Healthc. Syst. Eng. 2011, 1, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, H.L.; Clarke, P.S.; Sloane, M.D.; Lake, T.E.; Cheney, T.T. Effects of Hospital Care Environment on Patient Mortality and Nurse Outcomes. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2008, 38, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragon Penoyer, D. Nurse staffing and patient outcomes in critical care: A concise review. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 38, 1521–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, T.B.; Saab, B.J.; Mansuy, I.M. Neural Mechanisms of Stress Resilience and Vulnerability. Neuron 2012, 75, 747–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S.; Gray, J.D.; Nasca, C. Recognizing resilience: Learning from the effects of stress on the brain. Neurobiol. Stress 2015, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobasa, S.C. Stressful life events, personality, and health—Inquiry into hardiness 37. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1979, 37, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R. From psychological stress to the emotions: A history of changing outlooks. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1993, 44, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, J.; Li, J. Associations of Extrinsic and Intrinsic Components of Work Stress with Health: A Systematic Review of Evidence on the Effort-Reward Imbalance Model. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesselroade, J.; Salthouse, T. Methodological and Theoretical Implications of Intraindividual Variability in Perceptual-Motor Performance. J. Gerontol. 2004, 59, P49–P55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besèr, A.; Sorjonen, K.; Wahlberg, K.; Peterson, U.; Nygren, Å.; Åsberg, M. Construction and evaluation of a self rating scale for stress-induced Exhaustion Disorder, the Karolinska Exhaustion Disorder Scale. Scand. J. Psychol. 2014, 55, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakusic, J.; Schaufeli, W.; Claes, S.; Godderis, L. Stress, burnout and depression: A systematic review on DNA methylation mechanisms. J. Psychosom. Res. 2017, 92, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schonfeld, I.S.; Verkuilen, J.; Bianchi, R. Inquiry Into the Correlation Between Burnout and Depression. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arapovic-Johansson, B.; Wåhlin, C.; Hagberg, J.; Kwak, L.; Björklund, C.; Jensen, I. Participatory work place intervention for stress prevention in primary health care. A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Work Org. Psychol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SMS-Track. SMS -Track Questionnaire 1.1.3. Available online: https://www.sms-track.com/ (accessed on 1 October 2013).

- Dallner, M.; Lindström, K.; Elo, A.-L.; Skogstad, A.; Gamberale, F.; Hottinen, V.; Knardahl, S.; Örhede, E. Användarmanual för QPSNordic, Frågeformulär om Psykologiska och Sociala Faktorer i Arbetslivet Utprovat i Danmark, Finland, Norge och Sverige; Arbetslivsrapport Solna: Stockholm, Sweden, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, A.-L.; Leppänen, A.; Jahkola, A. Validity of a single-item measure of stress symptoms. Scand. J. Work Env. Health 2003, 29, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arapovic-Johansson, B.; Wåhlin, C.; Kwak, L.; Björklund, C.; Jensen, I. Work-related stress assessed by a text message single-item stress question. Occup. Med. 2017, 67, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; de Jonge, J.; Janssen, P.; Schaufelli, W.B. Burnout and engagement at work as a function of demands and control. Scand. J. Work. Env. Health 2001, 27, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, U. Stress and Burnout in Healthcare Workers; Karolinska institutet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lisspers, J.; Nygren, A.; Soderman, E. Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HAD): Some psychometric data for a Swedish sample. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1997, 96, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, J.; Li, J.; Montano, D. Psychometric Properties of the Effort-Reward Imbalance Questionnaire; Department of Medical Sociology, Faculty of Medicine, Dûsseldorf University: Dûsseldorf, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- The National Board of Health and Welfare. Handbok för Utveckling av Effektivitetsindikatorer; The National Board of Health and Welfare: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016. Available online: www.socialstyrelsen.se (accessed on 15 December 2016).

- Robinson, W.S. Ecological correlations and the behavior of individuals. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 40, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deboeck, P.R.; Montpetit, M.A.; Bergeman, C.S.; Boker, S.M. Using Derivative Estimates to Describe Intraindividual Variability at Multiple Time Scales. Psychol. Methods 2009, 14, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S. Brain on stress: How the social environment gets under the skin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109 (Suppl. 2), 17180–17185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, A. An overview of epidemiological studies on seasonal affective disorder. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2009, 101, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, K.M.; Rothstein, H.R. Effects of Occupational Stress Management Intervention Programs: A Meta-Analysis. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2008, 13, 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, H. Stressors and Stressor Appraisals: The Moderating Effect of Task Efficacy. J. Bus. Psychol. 2018, 33, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Sanz-Vergel, A.I. Weekly work engagement and flourishing: The role of hindrance and challenge job demands. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 83, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linzer, M.; Visser, M.R.M.; Oort, F.J.; Smets, E.M.A.; McMurray, J.E.; de Haes, H.C.J.M. Predicting and preventing physician burnout: Results from the United States and the Netherlands. Am. J. Med. 2001, 111, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulou, E.; Montgomery, A.; Benos, A. Burnout in internal medicine physicians: Differences between residents and specialists. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2006, 17, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connell, R.; Fawcett, B.; Meagher, G. Neoliberalism, New Public Management and the human service professions: Introduction to the Special Issue. J. Sociol. 2009, 45, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradburn, N.M.; Rips, L.J.; Shevell, S.K. Answering autobiographical questions: The impact of memory and inference on surveys. Science 1987, 236, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cogn. Psychol. 1973, 207–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, N.; Davis, A.; Rafaeli, E. Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2003, 54, 579–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harari, G.M.; Lane, N.D.; Wang, R.; Crosier, B.S.; Campbell, A.T.; Gosling, S.D. Using Smartphones to Collect Behavioral Data in Psychological Science: Opportunities, Practical Considerations, and Challenges. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. A J. Assoc. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 11, 838–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R.J.; Swerdlik, M.E.; Sturman, E.D. Psychological Testing and Assessment: An Introduction to Tests and Measurement, 8th ed.; Mc Grew-Hill Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| SMS Series 1 | SMS Series 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-Group a | M | Sd | M | Sd |

| LL | <3.462 | <0.927 | <2.999 | <1.067 |

| LH | <3.462 | ≥0.927 | <2.999 | ≥1.067 |

| HL | ≥3.462 | <0.927 | ≥2.999 | <1.067 |

| HH | ≥3.462 | ≥0.927 | ≥2.999 | ≥1.067 |

| Baseline(a) | SMS 1 80% of Weeks(b) | 6 Month Follow Up(c) | SMS 2 80% of Weeks(d) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N = 89 | N = 80 | N = 97 | N = 80 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 75 (84.3) | 69 (86.3) | 81 (84) | 69 (86) |

| Male | 14 (15.7) | 11 (13.7) | 16 (16) | 11 (14) |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 46.1 (11.6) | 46.3 (11.6) | 45.9 (11.8) | 46.0 (11.7) |

| Working hours 1, mean (SD) | 37.5 (5.3) | 37.5 (4.9) | 36.5 (6.4) | 36.8 (5.3) |

| Overtime work 2, mean, (SD) | 8.1 (26.8) | 5.4 (7.0) | 5.7 (9.4) | 4.6 (7.3) |

| Overall health 3, mean (SD) | 2.0 (0.8) | 2.0 (0.8) | 2.0 (.7) | 2.0 (0.7) |

| Formal ed. level, n (%) | ||||

| Comprehensive school | - | - | - | |

| Secondary school | 15 (17) | 15 (19) | 15 (16) | 12 (15) |

| University education | 71 (80) | 63 (79) | 80 (82) | 68 (85) |

| Higher academic ed. | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | - |

| Type of household, n (%) | ||||

| One person household | 16 (18) | 15 (19) | 14 (14) | 13 (16) |

| Single parent | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 3 (4) |

| Couple without children | 30 (34) | 27 (34) | 33 (34) | 27 (34) |

| Couple with children | 41 (46) | 36 (45) | 47 (49) | 37 (46.) |

| Years at this organization, n (%) | ||||

| Less than 1 year | 11 (12) | 8 (10) | 18 (18) | 11 (13.8) |

| 1–2 years | 22 (25) | 22 (28) | 15 (15) | 14 (17.5) |

| 3–5 years | 23 (26) | 20 (25) | 24 (25) | 21 (26.3) |

| 6–10 years | 14 (16) | 13 (16) | 18 (19) | 17 (21.3) |

| More than 10 years | 19 (21) | 17 (21) | 22 (23) | 17 (21.3) |

| Profession, n (%) | ||||

| Nurse | 25 (28) | 23 (29) | 31 (32) | 25 (31.3) |

| Physiotherapist | 12 (13) | 12 (15) | 16 (17) | 15 (18.8) |

| Physician | 13 (15) | 10 (13) | 11 (11) | 7 (8.8) |

| Medical secretary | 11 (12) | 11 (14) | 10 (10) | 8 (10) |

| Midwife | 8 (9) | 6 (7) | 7 (7) | 5 (6.3) |

| Laboratory technician | 5 (6) | 4 (5) | 6 (6) | 6 (7.5) |

| Assistant nurse | 6 (7) | 6 (7) | 6 (6) | 5 (6.3) |

| Counselor | 5 (6) | 4 (5) | 5 (5) | 4 (5.0) |

| Manager/Assist. Man. | 3 (3) | 3 (4) | 4 (4) | 4 (5.0) |

| Dietitian | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1.3) |

| Variable 1 | Total Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| b | 95% CI | p | |

| Time (Hours worked) | 0.163 | 0.128; 0.198 | 0.001 |

| Total amount of tasks | 0.155 | 0.122; 0.187 | 0.001 |

| No of patient visits | 0.277 | 0.215; 0.339 | 0.001 |

| No of administrative tasks | 0.465 | 0.356; 0.575 | 0.001 |

| No of calls answered | 0.520 | 0.412; 0.628 | 0.001 |

| Ratio time/total tasks | 9.133 | 6.90; 11.36 | 0.001 |

| Ratio time/patient visits | 3.241 | 2.27; 4.21 | 0.001 |

| Ratio time/admin. tasks | 1.791 | 1.35; 2.23 | 0.001 |

| Ratio time/calls answered | 2.099 | 1.54; 2.57 | 0.001 |

| SMS 1 Series (12 Weeks) | SMS 2 Series (26 Weeks) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR a | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |||

| Exp(B) | Lower | Upper | Exp(B) | Lower | Upper | |

| Variables | (A) Subgroups created using common (M) and (SD) | |||||

| Over-commitment1 | ||||||

| LH | 1.186 | 1.007 | 1.397 | 1.082 | 0.926 | 1.265 |

| HL | 1.345 | 1.137 | 1.592 | 1.249 | 1.064 | 1.465 |

| HH | 1.038 | 0.843 | 1.277 | 1.233 | 1.045 | 1.455 |

| Depression2 | ||||||

| LH | 1.104 | 0.841 | 1.449 | 0.885 | 0.620 | 1.262 |

| HL | 1.386 | 1.087 | 1.766 | 1.360 | 1.090 | 1.697 |

| HH | 0.972 | 0.662 | 1.428 | 1.142 | 0.895 | 1.456 |

| Exhaustion3 | ||||||

| LH | 1.167 | 0.994 | 1.371 | 1.101 | 0.916 | 1.324 |

| HL | 1.490 | 1.231 | 1.804 | 1.371 | 1.125 | 1.670 |

| HH | 0.984 | 0.806 | 1.201 | 1.350 | 1.102 | 1.653 |

| (B) Subgroups created using the rate of change (first derivative) | ||||||

| Over-commitment1 | ||||||

| LH | 0.933 | 0.794 | 1.096 | 0.997 | 0.852 | 1.167 |

| HL | 1.189 | 1.028 | 1.375 | 1.189 | 1.016 | 1.391 |

| HH | 1.004 | 0.840 | 1.199 | 1.234 | 1.050 | 1.451 |

| Depression2 | ||||||

| LH | 1.101 | 0.842 | 1.439 | 0.977 | 0.726 | 1.315 |

| HL | 1.351 | 1.064 | 1.715 | 1.285 | 1.026 | 1.609 |

| HH | 1.103 | 0.809 | 1.503 | 1.278 | 1.020 | 1.600 |

| Exhaustion3 | ||||||

| LH | 0.951 | 0.821 | 1.102 | 1.094 | 0.924 | 1.296 |

| HL | 1.269 | 1.090 | 1.477 | 1.283 | 1.054 | 1.562 |

| HH | 1.028 | 0.869 | 1.216 | 1.463 | 1.180 | 1.814 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arapovic-Johansson, B.; Wåhlin, C.; Hagberg, J.; Kwak, L.; Axén, I.; Björklund, C.; Jensen, I. Experience of Stress Assessed by Text Messages and Its Association with Objective Workload—A Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 680. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030680

Arapovic-Johansson B, Wåhlin C, Hagberg J, Kwak L, Axén I, Björklund C, Jensen I. Experience of Stress Assessed by Text Messages and Its Association with Objective Workload—A Longitudinal Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(3):680. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030680

Chicago/Turabian StyleArapovic-Johansson, Bozana, Charlotte Wåhlin, Jan Hagberg, Lydia Kwak, Iben Axén, Christina Björklund, and Irene Jensen. 2020. "Experience of Stress Assessed by Text Messages and Its Association with Objective Workload—A Longitudinal Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 3: 680. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030680

APA StyleArapovic-Johansson, B., Wåhlin, C., Hagberg, J., Kwak, L., Axén, I., Björklund, C., & Jensen, I. (2020). Experience of Stress Assessed by Text Messages and Its Association with Objective Workload—A Longitudinal Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 680. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030680