How Have Public Safety Personnel Seeking Digital Mental Healthcare Been Affected by the COVID-19 Pandemic? An Exploratory Mixed Methods Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context and Timeline

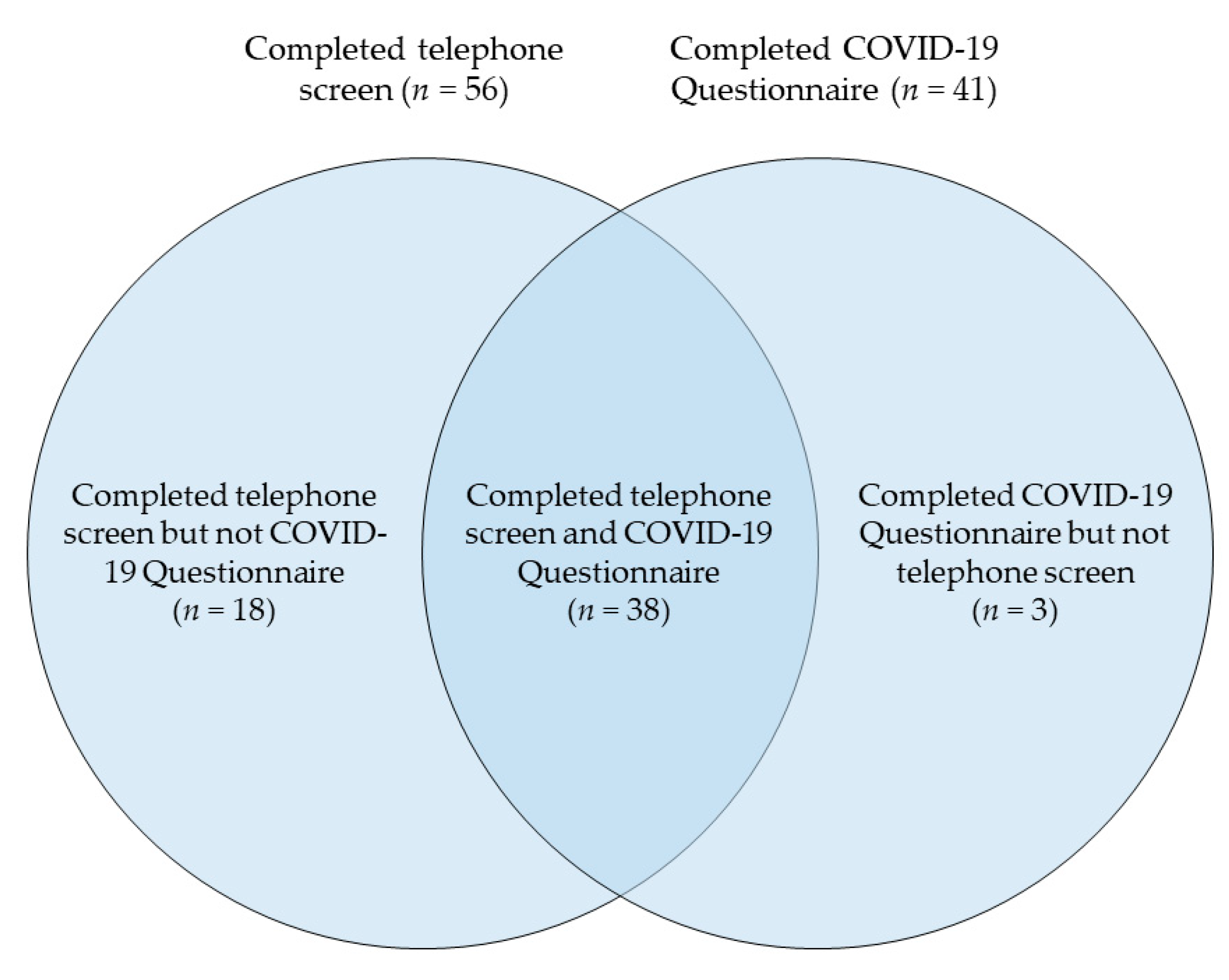

2.2. Procedure and Participants

2.3. Data and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Results of COVID-19 Questionnaire

3.3. Results of Qualitative Analyses of Telephone Screens

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Canadian Institute for Public Safety Research and Treatment. Glossary of Terms: A Shared Understanding of the Common Terms Used to Describe Psychological Trauma (Version 2.0). 2019. Available online: https://www.cipsrt-icrtsp.ca/en/resources/glossary-of-terms (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Carleton, R.N.; Afifi, T.O.; Turner, S.; Taillieu, T.; Duranceau, S.; LeBouthillier, D.M.; Sareen, J.; Ricciardelli, R.; MacPhee, R.S.; Groll, D.; et al. Mental Disorder Symptoms among Public Safety Personnel in Canada. Can. J. Psychiatry 2018, 63, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carleton, R.N.; Afifi, T.O.; Turner, S.; Taillieu, T.; LeBouthillier, D.M.; Duranceau, S.; Sareen, J.; Ricciardelli, R.; MacPhee, R.S.; Groll, D.; et al. Suicidal ideation, plans, and attempts among public safety personnel in Canada. Can. Psychol./Psychol. Can. 2018, 59, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. Rates of Selected Mental or Substance Use Disorders, Lifetime and 12 Month, Canada, Household Population 15 and Older; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Carleton, R.N.; Afifi, T.O.; Taillieu, T.; Turner, S.; Krakauer, R.; Anderson, G.S.; MacPhee, R.S.; Ricciardelli, R.; Cramm, H.A.; Groll, D.; et al. Exposures to potentially traumatic events among public safety personnel in Canada. Can. J. Behav. Sci./Rev. Can. Des Sci. Du Comport. 2019, 51, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ameringen, M.; Mancini, C.; Patterson, B.; Boyle, M.H. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Canada. Cns Neurosci. Ther. 2008, 14, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association (Ed.) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-89042-554-1. [Google Scholar]

- Carleton, R.N.; Afifi, T.O.; Taillieu, T.; Turner, S.; Mason, J.E.; Ricciardelli, R.; McCreary, D.R.; Vaughan, A.D.; Anderson, G.S.; Krakauer, R.L.; et al. Assessing the Relative Impact of Diverse Stressors among Public Safety Personnel. Intern. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R.N.; Afifi, T.O.; Turner, S.; Taillieu, T.; Vaughan, A.D.; Anderson, G.S.; Ricciardelli, R.; MacPhee, R.S.; Cramm, H.A.; Czarnuch, S.; et al. Mental health training, attitudes toward support, and screening positive for mental disorders. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2020, 49, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardelli, R.; Czarnuch, S.; Carleton, R.N.; Gacek, J.; Shewmake, J. Canadian Public Safety Personnel and Occupational Stressors: How PSP Interpret Stressors on Duty. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Advice for the Public 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Paluszek, M.M.; Landry, C.A.; Taylor, S.; Asmundson, G.J.G. The psychological sequelae of the COVID-19 pandemic: Psychological processes, current reearch ventures, and preparing for a postpandemic world. Behav. Ther. 2020, 43, 158–163. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Michelle_Paluszek/publication/342258521_The_Psychological_Sequelae_of_the_COVID-19_Pandemic_Psychological_Processes_Current_Research_Ventures_and_Preparing_for_a_Postpandemic_World/links/5efe0bd8a6fdcc4ca444ed94/The-Psychological-Sequelae-of-the-COVID-19-Pandemic-Psychological-Processes-Current-Research-Ventures-and-Preparing-for-a-Postpandemic-World.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Shultz, J.M.; Espinel, Z.; Flynn, B.W.; Hoffman, Y.; Cohen, R.E. DEEP PREP: All-Hazards Disaster Behavioural Health Training; Disaster Life Support Publishing: Tampa, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S. The Psychology of Pandemics: Preparing for the Next Global Outbreak of Infectious Disease; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-5275-4118-4. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, W.; Fang, Z.; Hou, G.; Han, M.; Xu, X.; Dong, J.; Zheng, J. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 287, 112934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Landry, C.A.; Paluszek, M.M.; Fergus, T.A.; McKay, D.; Asmundson, G.J.G. Development and initial validation of the COVID Stress Scales. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 72, 102232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titov, N.; Staples, L.; Kayrouz, R.; Cross, S.; Karin, E.; Ryan, K.; Dear, B.; Nielssen, O. Rapid report: Early demand, profiles and concerns of mental health users during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Internet Interv. 2020, 21, 100327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, J.; Shen, B.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Z.; Xie, B.; Xu, Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. Gen. Psychiatry 2020, 33, e100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.; Landry, C.A.; Paluszek, M.M.; Fergus, T.A.; McKay, D.; Asmundson, G.J.G. COVID stress syndrome: Concept, structure, and correlates. Depress. Anxiety 2020, 37, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stogner, J.; Miller, B.L.; McLean, K. Police Stress, Mental Health, and Resiliency during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Crim. Justice 2020, 45, 718–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heber, A.; Testa, V.; Smith-MacDonald, L.; Brémault-Phillips, S.; Carleton, R.N. Rapid response to COVID-19: Addressing challenges and increasing the mental readiness of public safety personnel. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. Res. Policy Pract. 2020, 40, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, H.C.; Hadjistavropoulos, H.D.; Burnett, J.L.; Beahm, J.D.; Carleton, R.N.; Fournier, A.K. Stakeholder perspectives on internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy for public safety personnel: A qualitative analysis. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardelli, R.; Carleton, R.N.; Mooney, T.; Cramm, H. “Playing the system”: Structural factors potentiating mental health stigma, challenging awareness, and creating barriers to care for Canadian public safety personnel. Health (Lond.) 2020, 24, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, G. Internet-Delivered Psychological Treatments. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 12, 157–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donker, T.; Blankers, M.; Hedman, E.; Ljótsson, B.; Petrie, K.; Christensen, H. Economic evaluations of Internet interventions for mental health: A systematic review. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 3357–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, H.C.; Sison, A.P.; Burnett, J.L.; Beahm, J.D.; Hadjistavropoulos, H.D. Exploring Perceptions of Internet-Delivered Cognitive Behaviour Therapy among Public Safety Personnel: Informing Dissemination Efforts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Outbreak Update—Canada.ca. 2020. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20200623024826/https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection.html?topic=tilelink (accessed on 24 October 2020).

- Giles, D. Saskatchewan Confirms First Presumptive Case of Novel Coronavirus. Global News. 2020. Available online: https://globalnews.ca/news/6666466/coronavirus-saskatchewan-covid-19-coronavirus-saskatoon/ (accessed on 24 October 2020).

- Giles, D. Saskatchewan Declares State of Emergency as Coronavirus Concerns Grow|Globalnews.ca. 2020. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20200318221045/https://globalnews.ca/news/6698018/saskatchewan-state-of-emergency-covid-19-coronavirus/ (accessed on 24 October 2020).

- COVID-19. Government of Saskatchewan. Available online: https://www.saskatchewan.ca/government/health-care-administration-and-provider-resources/treatment-procedures-and-guidelines/emerging-public-health-issues/2019-novel-coronavirus (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Foss, C.; Ellefsen, B. The value of combining qualitative and quantitative approaches in nursing research by means of method triangulation. J. Adv. Nurs. 2002, 40, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blevins, C.A.; Weathers, F.W.; Davis, M.T.; Witte, T.K.; Domino, J.L. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and Initial Psychometric Evaluation: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5. J. Trauma. Stress 2015, 28, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrenreich-May, J. Fear of Illness and Virus Evaluation Scales. 2020. Available online: https://adaa.org/sites/default/files/UofMiamiFear%20of%20Illness%20and%20Virus%20Evaluation%20(FIVE)%20scales%20for%20Child-%2C%20Parent-%20and%20Adult-Report.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2020).

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: A systematic review. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2010, 32, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bovin, M.J.; Marx, B.P.; Weathers, F.W.; Gallagher, M.W.; Rodriguez, P.; Schnurr, P.P.; Keane, T.M. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–Fifth Edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychol. Assess. 2016, 28, 1379–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manea, L.; Gilbody, S.; McMillan, D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): A meta-analysis. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2012, 184, E191–E196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levis, B.; Benedetti, A.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Sun, Y.; Negeri, Z.; He, C.; Wu, Y.; Krishnan, A.; Bhandari, P.M.; Neupane, D.; et al. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scores do not accurately estimate depression prevalence: Individual participant data meta-analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 122, 115–128.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortmann, J.H.; Jordan, A.H.; Weathers, F.W.; Resick, P.A.; Dondanville, K.A.; Hall-Clark, B.; Foa, E.B.; Young-McCaughan, S.; Yarvis, J.S.; Hembree, E.A.; et al. Psychometric analysis of the PTSD Checklist-5 (PCL-5) among treatment-seeking military service members. Psychol. Assess. 2016, 28, 1392–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QSR International. NVivo 12 Qualitative Data Analysis Software. 2018. Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W.; Wang, H.; Lin, Y.; Li, L. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 112936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Participants Who Completed COVID-19 Questionnaire (n = 41) | Participants Who Completed Telephone Screen (n = 56) | All Participants (N = 59) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, M (SD) | 40.13 (10.80) | 39.73 (10.20) | 39.73 (10.20) | |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Woman | 24 (59) | 32 (57) | 34 (58) | |

| Man | 16 (39) | 24 (43) | 24 (41) | |

| Other | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (2) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White | 32 (78) | 45 (80) | 46 (78) | |

| First Nations, Inuit, or Metis | 7 (17) | 7 (13) | 9 (15) | |

| Other | 2 (5) | 4 (7) | 4 (7) | |

| Married or common law, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 21 (51) | 31 (55) | 32 (54) | |

| No | 20 (49) | 25 (45) | 27 (46) | |

| Children, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 19 (46) | 27 (48) | 27 (46) | |

| No | 22 (54) | 29 (52) | 32 (54) | |

| Community size, n (%) | ||||

| Population of 100,000 or greater | 15 (37) | 30 (54) | 27 (46) | |

| Population under 100,000 | 26 (63) | 26 (46) | 32 (54) | |

| PSP Sector, n (%) | ||||

| Police | 14 (34) | 21 (38) | 21 (36) | |

| Corrections | 8 (20) | 9 (16) | 10 (17) | |

| Emergency Medical Service | 8 (20) | 11 (20) | 12 (20) | |

| Fire | 4 (10) | 4 (7) | 4 (7) | |

| Dispatch/Communications | 3 (7) | 5 (9) | 5 (8) | |

| Other | 4 (10) | 6 (11) | 7 (12) | |

| Clinical characteristics, M (SD) | ||||

| PHQ-9 score | 12.76 (6.30) | 12.11 (6.16) | 12.17 (6.28) | |

| GAD-7 score | 11.51 (5.92) | 10.79 (5.74) | 10.63 (5.77) | |

| PCL-5 score | 31.95 (19.68) | 30.93 (20.11) | 30.76 (19.61) | |

| Item | Frequency of Responses, n (%) | Mean Response, SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I Am Not Afraid of This at All (0) | I Am Afraid of This Some of the Time (1) | I Am Afraid of This Most of the Time (2) | I Am Afraid of This All of the Time (3) | ||

| 1. I am afraid I may get COVID-19. | 16 (39) | 22 (54) | 2 (5) | 1 (2) | 0.71 (0.68) |

| 2. I am afraid I will get very, very sick if I catch COVID-19. | 19 (46) | 18 (44) | 1 (2) | 3 (7) | 0.71 (0.84) |

| 3. I am afraid I will have to go to the hospital because of COVID-19. | 26 (63) | 14 (34) | 0 | 1 (2) | 0.41 (0.63) |

| 4. I am afraid I might die if I get COVID-19. | 27 (66) | 12 (29) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0.41 (0.67) |

| 5. I am afraid my pet might get COVID-19. | 33 (80) | 6 (15) | 2 (5) | 0 | 0.24 (0.54) |

| 6. I am afraid a family member might get sick or die because of COVID-19. | 5 (12) | 21 (51) | 9 (22) | 6 (15) | 1.39 (0.89) |

| 7. I am afraid I may do something that would cause someone else to get COVID-19. | 12 (29) | 20 (49) | 4 (10) | 5 (12) | 1.05 (0.95) |

| 8. I am afraid a friend might get sick or die because of COVID-19. | 18 (44) | 18 (44) | 5 (12) | 0 | 0.68 (0.69) |

| 9. I am afraid people in the world might get sick or die because of COVID-19. | 25 (61) | 12 (29) | 4 (10) | 0 | 0.49 (0.68) |

| Impact | Participants (n = 41) | |

|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 status, n (%) | ||

| Recovered | 1 (2) | |

| Never infected | 40 (98) | |

| Someone close to participant has had COVID-19, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 5 (12) | |

| No | 36 (88) | |

| Childcare issues related to COVID-19, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 6 (15) | |

| No | 13 (32) | |

| No children | 22 (54) | |

| Lost job or income due to COVID-19, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 4 (10) | |

| No | 37 (90) | |

| Impact of COVID-19 on ability to meet financial obligations, n (%) | ||

| Too soon to tell | 1 (2) | |

| No impact | 4 (10) | |

| Minor impact | 4 (10) | |

| Moderate impact | 29 (71) | |

| Major impact | 3 (7) | |

| Concern about ability to maintain physical distance at work, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 23 (56) | |

| No | 18 (44) | |

| Difficulties with feeling socially isolated due to COVID-19, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 15 (37) | |

| No | 26 (63) | |

| Being afraid of COVID-19 has gotten in the way of enjoying life, n (%) | ||

| Not true for participant at all | 24 (59) | |

| Somewhat true | 16 (39) | |

| Mostly true | 1 (2) | |

| Definitely true | 0 | |

| Being afraid of COVID-19 has caused strong emotions, n (%) | ||

| Not true for participant at all | 18 (44) | |

| Somewhat true | 17 (41) | |

| Mostly true | 4 (10) | |

| Definitely true | 2 (5) | |

| Domain/Theme | Definition | Participants (n = 56) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative emotions, n (%) | 22 (39) | ||

| Fear of others contracting COVID-19 | Fears about loved ones or co-workers contracting the virus, getting sick, or dying. | 12 (21) | |

| Fear of contracting COVID-19 | Fears about themselves contracting the virus, getting sick, or dying. | 8 (14) | |

| Isolation | Negative emotions resulting from physical distancing measures leading to isolation. | 5 (9) | |

| Boredom | Boredom due to closures. | 3 (5) | |

| General stress | Increased overall stress levels. | 5 (9) | |

| Logistical impacts, n (%) | 17 (30) | ||

| Impact on work | Concerns included increased call volumes, the inability of the healthcare system to manage the impact of COVID-19, and concerns about management not taking the pandemic seriously. | 6 (11) | |

| Financial concerns | Financial concerns included reduced business in secondary businesses, partners losing job/income, or reduced shifts/hours. | 6 (11) | |

| Reduced access to support | Closures affecting access to support for participants themselves or their family members. | 5 (9) | |

| Impact on home life | Concerns were related to not having access to childcare and having to navigate a new routine. | 4 (7) | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McCall, H.; Beahm, J.; Landry, C.; Huang, Z.; Carleton, R.N.; Hadjistavropoulos, H. How Have Public Safety Personnel Seeking Digital Mental Healthcare Been Affected by the COVID-19 Pandemic? An Exploratory Mixed Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9319. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249319

McCall H, Beahm J, Landry C, Huang Z, Carleton RN, Hadjistavropoulos H. How Have Public Safety Personnel Seeking Digital Mental Healthcare Been Affected by the COVID-19 Pandemic? An Exploratory Mixed Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(24):9319. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249319

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcCall, Hugh, Janine Beahm, Caeleigh Landry, Ziyin Huang, R. Nicholas Carleton, and Heather Hadjistavropoulos. 2020. "How Have Public Safety Personnel Seeking Digital Mental Healthcare Been Affected by the COVID-19 Pandemic? An Exploratory Mixed Methods Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 24: 9319. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249319

APA StyleMcCall, H., Beahm, J., Landry, C., Huang, Z., Carleton, R. N., & Hadjistavropoulos, H. (2020). How Have Public Safety Personnel Seeking Digital Mental Healthcare Been Affected by the COVID-19 Pandemic? An Exploratory Mixed Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9319. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249319