Analysis of the Athletic Career and Retirement Depending on the Type of Sport: A Comparison between Individual and Team Sports

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

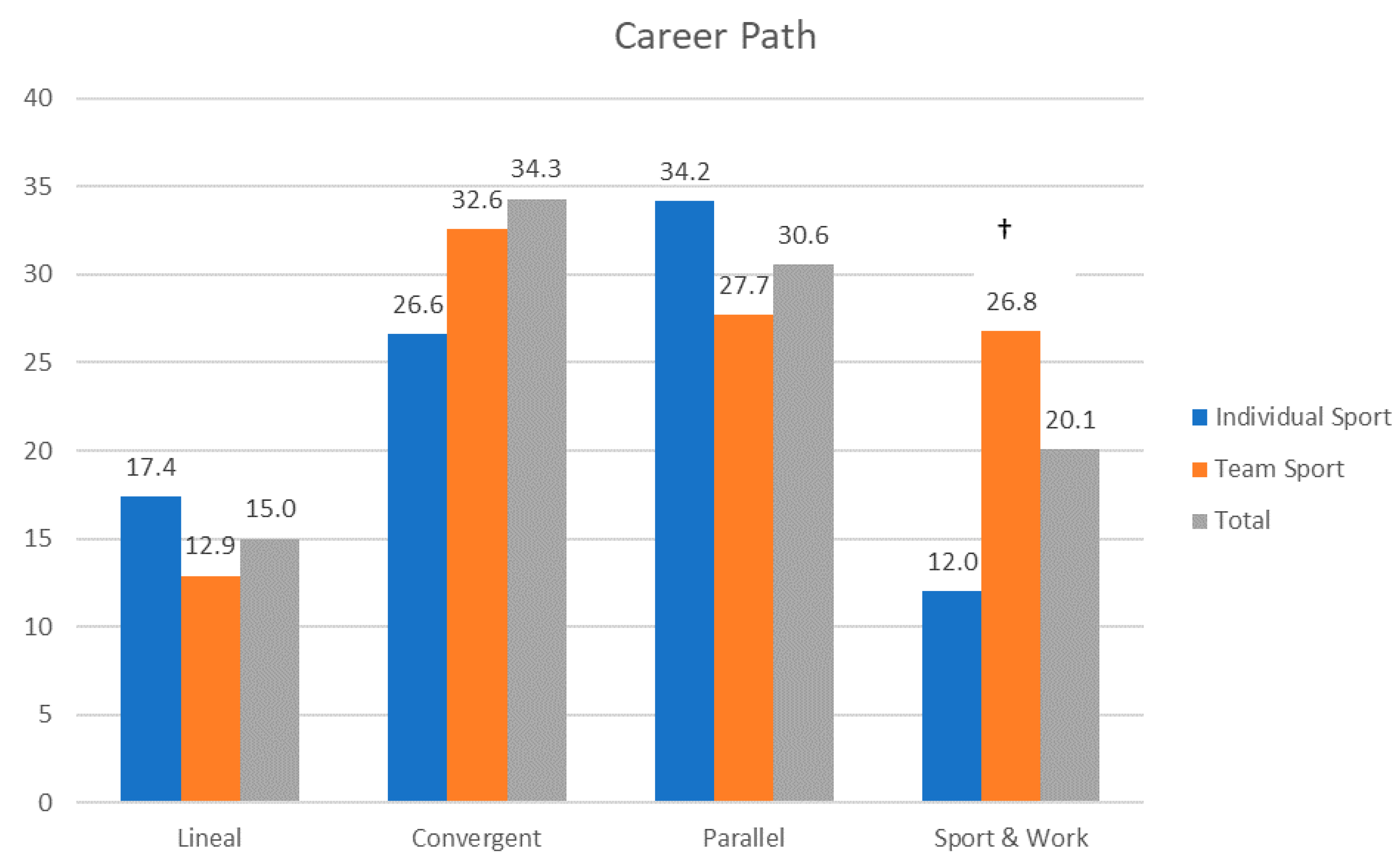

3.1. Athletic Career and Career Path

3.2. Sport Retirement

3.3. Employment and Current Lifestyle

4. Discussion

4.1. Athletic Career and Career Path

4.2. Sport Retirement

4.3. Employment and Current Lifestyle

4.4. Limitations

4.5. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stambulova, N.; Wylleman, P. Athletes’ career development and transitions. In International Perspectives on Key Issues in Sport and Exercise Psychology. Routledge Companion to Sport and Exercise Psychology: Global Perspectives and Fundamental Concepts; Papaioannou, A.G., Hackfort, D., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2014; pp. 605–620. [Google Scholar]

- Stambulova, N. Symptoms of a crisis-transition: A grounded theory study. In SIPF Yearbook 2003; Hassmén, N., Ed.; Örebro University Press: Örebro, Sweden, 2003; pp. 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Wylleman, P. A Holistic and Mental Health Perspective on Transitioning Out of Elite Sport. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology; 2019; Available online: https://oxfordre.com/psychology/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.001.0001/acrefore-9780190236557-e-189 (accessed on 21 October 2020).

- Côté, J.; Vierimaa, M. The developmental model of sport participation: 15 years after its first conceptualization. Sci. Sports 2014, 29, S63–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylleman, P.; Rosier, N. Holistic perspective on the development of elite athletes. In Sport and Exercise Psychology Research: From Theory to Practice; Raab, M., Wylleman, P., Seiler, R., Elbe, A.-M., Hatzigeorgiadis, A., Eds.; Elsevier Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlossberg, N.K. A model for analyzing human adaptation to transition. Couns. Psychol. 1981, 9, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stambulova, N.; Stephan, Y.; Japhag, U. Athletic retirement: A cross-national comparison of elite French and Swedish athletes. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2007, 8, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stambulova, N.B.; Wylleman, P. Psychology of athletes’ dual careers: A state-of-the-art critical review of the European discourse. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 42, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronkainen, N.J.; Ryba, T.V. Understanding youth athletes’ life designing processes through dream day narratives. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 108, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stambulova, N.B.; Engstrom, C.; Franck, A.; Linner, L.; Lindahl, K. Searching for an optimal balance: Dual career experiences of Swedish adolescent athletes. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 21, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.J.; Harwood, C.G.; Sellars, P.A. Supporting adolescent athletes’ dual careers: The role of an athlete’s social support network. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2018, 38, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilina, D. A study of the relationship between elite athletes’ educational development and sporting performance. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2013, 30, 374–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiansen, E. Walking the line: How young athletes balance academic studies and sport in international competition. Sport Soc. 2017, 20, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorkkila, M.; Aunola, K.; Salmela-Aro, K.; Tolvanen, A.; Ryba, T.V. The co-developmental dynamic of sport and school burnout among student-athletes: The role of achievement goals. Scand. J. Med. Sci.Sports 2018, 28, 1731–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torregrossa, M.; Chamorro, J.L.; Prato, L.; Ramis, Y. Groups, environmental and Athletic career [Grupos, Entornos y Carrera Deportiva]. In Sports Groups Management; [Dirección de grupos deportivos]; García Calvo, T., Leo, F.M., Cervelló, E., Eds.; Editorial Tirant lo Blanch: Barcelona, Spain, in press.

- Barriopedro, M.; López de Subijana, C.; Muniesa, C.; Ramos, J.; Guidotti, F.; Lupo, C. Retirement difficulties in spanish athletes: The importance of the career path. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2019, 8, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knights, S.; Sherry, E.; Ruddock-Hudson, M.; O’Halloran, P. The end of a professional sport career: Ensuring a positive transition. J. Sport Manag. 2019, 33, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; Fogarty, G.; Albion, M. Changes in athletic identity and life satisfaction of elite athletes as a function of retirement status. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2014, 26, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.J.; Webb, T.L.; Robinson, M.A.; Cotgreave, R. Athletes’ experiences of social support during their transition out of elite sport: An interpretive phenomenological analysis. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2018, 36, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro, J.L.; Torregrosa, M.; Sanchez-Miguel, P.A.; Sanchez-Oliva, D.; Amado, D. Challenges in the transition to elite football: Coping resources in males and females. RIPED Ibero Am. J. Exerc. Sports Psychol. 2015, 10, 113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Torregrosa, M.; Ramis, Y.; Pallarés, S.; Azócar, F.; Selva, C. Olympic athletes back to retirement: A qualitative longitudinal study. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 21, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siekanska, M.; Blecharz, J. Transitions in the Careers of Competitive Swimmers: To Continue or Finish with Elite Sport? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willard, V.C.; Lavallee, D. Retirement experiences of elite ballet dancers: Impact of self-identity and social support. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2016, 5, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosh, S.; Tully, P.J. Stressors, Coping, and Support Mechanisms for Student Athletes Combining Elite Sport and Tertiary Education: Implications for Practice. Sport Psychol. 2015, 29, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriopedro, M.; de Subijana, C.L.; Muniesa, C. Insights into life after sport for Spanish Olympians: Gender and career path perspectives. PLoS ONE 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conzelmann, A.; Nagel, S. Professional careers of the german olympic athletes. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2003, 38, 259–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López de Subijana Hernández, C.; Barriopedro Moro, M.; Conde Pascual, E.; Sánchez Sánchez, J.; Ubago Guisado, E.; Gallardo Guerrero, L. Analysis of the Perceived barriers of the spanish’s elite athletes to studies access. Análisis de las barreras percibidas por los deportistas de élite españoles para acceder a los estudios. Cuad. Psicol. Deporte 2015, 15, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Baron-Thiene, A.; Alfermann, D. Personal characteristics as predictors for dual career dropout versus continuation—A prospective study of adolescent athletes from German elite sport schools. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 21, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez de Subijana, C.; Barriopedro, M.I.; Sanz, I. Dual career motivation and athletic identity on elite athletes. Sport Psychol. J. 2015, 24, 55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Torregrossa, M.; Conde, E.; Perez-Rivases, A.; Soriano, G.; Ramis, Y. Former elite athletes’ current sport and physical activity La actividad física y el deporte saludable en exdeportistas de élite. Cuad. Psicol. Deporte 2019, 19, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bäckmand, H.; Kujala, U.; Sarna, S.; Kaprio, J. Former Athletes’ Health-Related Lifestyle Behaviours and Self-Rated Health in Late Adulthood. Int. J. Sports Med. 2010, 31, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, S.A.; Adamo, K.B.; Hamel, M.E.; Hardt, J.; Gorber, S.C.; Tremblay, M. A comparison of direct versus self-report measures for assessing physical activity in adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Heatlth Organization (WHO). Physically Active. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/physical-activity#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Abel, M.G.; Carreiro, B. Preparing for the Big Game: Transitioning From Competitive Athletics to a Healthy Lifestyle. Strength Cond. J. 2011, 33, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consejo Superior de Deportes Web Page. Deportistas de Alto Nivel. Available online: https://www.csd.gob.es/es/alta-competicion/deporte-de-alto-nivel-y-alto-rendimiento (accessed on 27 September 2020).

- Comité Olímpico Español (COE). Spanish Olympic Committee. Available online: https://www.coe.es/2012/HOMEDEP2012.nsf/2012FDEPORTISTAN2?OpenForm (accessed on 27 September 2020).

- Alcaraz, S.; Jordana, A.; Pons, J.; Borrueco, M.; Ramis, Y. Maximum information, Minimum discomfort. Shortening questionnaires to take care of participants in sport psychology. [Máxima Información, Mínima Molestia (MIMO): Reducir cuestionarios para cuidar de las personas participantes en psicología del deporte]. Inf. Psicol. 2020, 119, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriopedro, M.; Muniesa, C.A.; López de Subijana, C. Perspectiva de Género en la Inserción Laboral de los Deportistas Olímpicos Españoles. Cuad. Psicol. Deporte 2016, 16, 339–350. [Google Scholar]

- González, M.D.; Torregrosa, M. Análisis de la retirada de la competición de élite: Antecedentes, transición y consecuencias. RIPED Ibero Am. J. Exerc. Sports Psychol. 2009, 4, 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Alfermann, D.; Stambulova, N.; Zemaityte, A. Reactions to sport career termination: A cross-national comparison of German, Lithuanian, and Russian athletes. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2004, 5, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, F.J. Survey Research Methods; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, D.M. Research and Evaluation in Education and Psychology: Integrating Diversity with Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Methods, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Horvarth, S.; Röthlin, P. How to improve athletes’ return of investment: Shortening questionnaires in the applied sport psychology setting. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2018, 30, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López de Subijana, C.; Barriopedro, M.; Muniesa, C.A.; Gómez, M.A. A Bright Future for the Elite Athletes?: The Importance of the Career Path; Final Report for the IOC Olympic Studies Centre; Universidad Politécnica de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M. Qualitative Research. In Encyclopedia of Statistics in Behavioral Science; Everitt, B.S., Howell, D.C., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2005; Volume 3, pp. 1633–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Earlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Agresti, A. Categorical Data Analysis, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 4th ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, P.L.; Gardner, R.C. Type 1 error rate comparisons of post hoc procedures for I J chi-square tables. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2000, 60, 735–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, J.; Lavallee, D. An investigation of potential users of career transition services in the United Kingdom. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2004, 5, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekavc, J.; Wylleman, P.; Erpič, S.C. Perceptions of dual career development among elite level swimmers and basketball players. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 21, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erpič, S.C.; Wylleman, P.; Zupancic, M. The effect of athletic and non- athletic factors on the sports career termination process. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2004, 5, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Unemployment Rate-Annual Data. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/en/web/products-datasets/-/TIPSUN20 (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Eurobarometer 472 Sport and Physical Activity. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Survey/index#p=1&instruments=SPECIAL (accessed on 10 September 2020).

| Individual Sport | Team Sport | Total | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | 95% CI | M | SD | 95% CI | M | SD | 95% CI | ||||

| Variable | LL | UL | LL | UL | LL | UL | ||||||

| Beginning to practice | 10.7 | 4.8 | 10.0 | 11.4 | 10.9 | 3.8 | 10.5 | 11.4 | 10.8 | 4.2 | 10.4 | 11.3 |

| Entering the elite level * | 17.5 | 4.0 | 16.9 | 18.1 | 18.1 | 2.9 | 17.7 | 18.4 | 17.8 | 3.4 | 17.5 | 18.1 |

| Maximum achievement ** | 23.0 | 5.4 | 22.2 | 23.7 | 24.9 | 4.5 | 24.3 | 25.5 | 24.0 | 5.0 | 23.6 | 24.5 |

| Retirement ** | 27.7 | 6.8 | 26.8 | 28.7 | 31.8 | 5.1 | 31.2 | 32.5 | 30.0 | 6.3 | 29.4 | 30.6 |

| Length elite stage ** | 10.3 | 5.3 | 9.5 | 11.1 | 13.8 | 4.9 | 13.2 | 14.4 | 12.2 | 5.3 | 11.7 | 12.8 |

| Length athletic career ** | 17.0 | 6.4 | 16.1 | 18.0 | 20.9 | 5.8 | 20.1 | 21.7 | 19.2 | 6.4 | 18.5 | 19.8 |

| Length in elite up to the maximum achievement ** | 5.4 | 3.9 | 4.9 | 6.0 | 6.9 | 4.2 | 6.3 | 7.5 | 6.2 | 4.2 | 5.8 | 6.6 |

| Length from maximum achievement until retirement ** | 4.9 | 3.8 | 4.3 | 5.4 | 7.0 | 4.3 | 6.4 | 7.5 | 6.0 | 4.2 | 5.6 | 6.4 |

| Individual Sports | Team Sports | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retirement Features | % (n = 185) | % (n = 225) | % (n = 410) | |

| Timing retirement | Radical | 64.9 | 67.6 | 66.3 |

| Gradual | 35.1 | 32.4 | 33.7 | |

| Voluntariness | Voluntary | 79.3 | 85.3 | 82.6 |

| Involuntary | 20.7 | 14.7 | 17.4 | |

| Planned * | No | 65.9 | 54.2 | 59.5 |

| Yes | 34.1 | 45.8 | 40.5 | |

| Economic and working situation at retirement * | Completely solved | 13.1 | 18.8 | 16.3 |

| Mostly solved | 19.1 | 35.9 † | 28.3 | |

| I had only occasional jobs | 19.1 | 17.5 | 18.2 | |

| I had hardly anything | 48.6 † | 27.8 | 37.2 |

| Individual Sport | Team Sport | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment Status and Salary | % (n = 185) | % (n = 225) | % (n = 410) | |

| Working status | Yes, working | 88.6 | 87.6 | 88.0 |

| Not working and looking for a job | 9.7 | 9.3 | 9.5 | |

| Not working and not looking for a job | 1.6 | 3.1 | 2.4 | |

| (n = 160) | (n = 180) | (n = 340) | ||

| Monthly income | Up to 1499 € | 37.5 | 34.4 | 35.9 |

| 1500–2499 € | 41.9 | 37.8 | 39.7 | |

| more than 2500 € | 20.6 | 27.8 | 24.4 | |

| Relation with Sport Nowadays | (n = 176) | (n = 214) | (n = 390) | |

| I do physical activity or practice sport | No | 7.4 | 9.8 | 8.7 |

| Yes | 92.6 | 90.2 | 91.3 | |

| I compete in veterans’ events * | No | 70.6 | 60.6 | 65.3 |

| Yes | 29.4 | 39.4 | 34.7 | |

| I keep in touch with my coaches | No | 29.5 | 31.3 | 30.4 |

| Yes | 70.5 | 68.7 | 69.6 | |

| I have a job related to sport | No | 53.6 | 52.9 | 53.3 |

| Yes | 46.4 | 47.1 | 46.7 | |

| I attend sports events as a spectator * | No | 35.9 | 22.2 | 28.5 |

| Yes | 64.1 | 77.8 | 71.5 | |

| I counsel young athletes | No | 41.5 | 42.6 | 42.1 |

| Yes | 58.5 | 57.4 | 57.9 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Subijana, C.L.; Galatti, L.; Moreno, R.; Chamorro, J.L. Analysis of the Athletic Career and Retirement Depending on the Type of Sport: A Comparison between Individual and Team Sports. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9265. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249265

de Subijana CL, Galatti L, Moreno R, Chamorro JL. Analysis of the Athletic Career and Retirement Depending on the Type of Sport: A Comparison between Individual and Team Sports. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(24):9265. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249265

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Subijana, Cristina López, Larisa Galatti, Rubén Moreno, and Jose L. Chamorro. 2020. "Analysis of the Athletic Career and Retirement Depending on the Type of Sport: A Comparison between Individual and Team Sports" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 24: 9265. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249265

APA Stylede Subijana, C. L., Galatti, L., Moreno, R., & Chamorro, J. L. (2020). Analysis of the Athletic Career and Retirement Depending on the Type of Sport: A Comparison between Individual and Team Sports. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9265. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249265