Experiencing Nature to Satisfy Basic Psychological Needs in Parenting: A Quasi-Experiment in Family Shelters

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Impact of Living in a Shelter on Parents’ Opportunities for Need Fulfillment

1.2. Experiencing Nature to Support Parents in Their Need Fulfillment

1.3. The Aim of This Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Design and Procedures

2.3. Intervention

2.3.1. Nature Experience

2.3.2. Comparison Condition

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Measurements

2.5.1. Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration

2.5.2. Connectedness to Nature

2.5.3. Children’s Age and Shelter Type

2.6. Quality of Measurements

2.6.1. Training

2.6.2. Setting Conditions

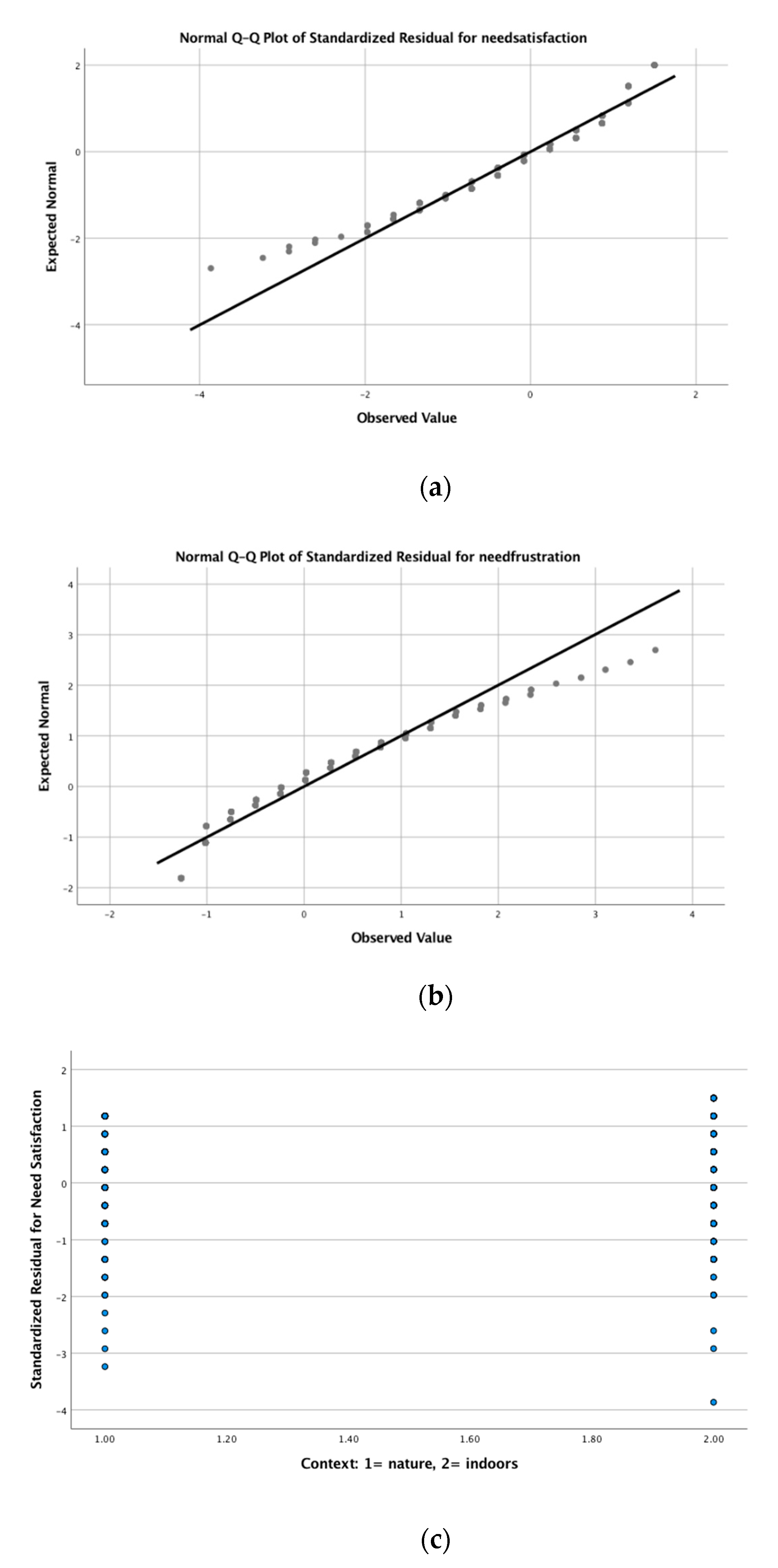

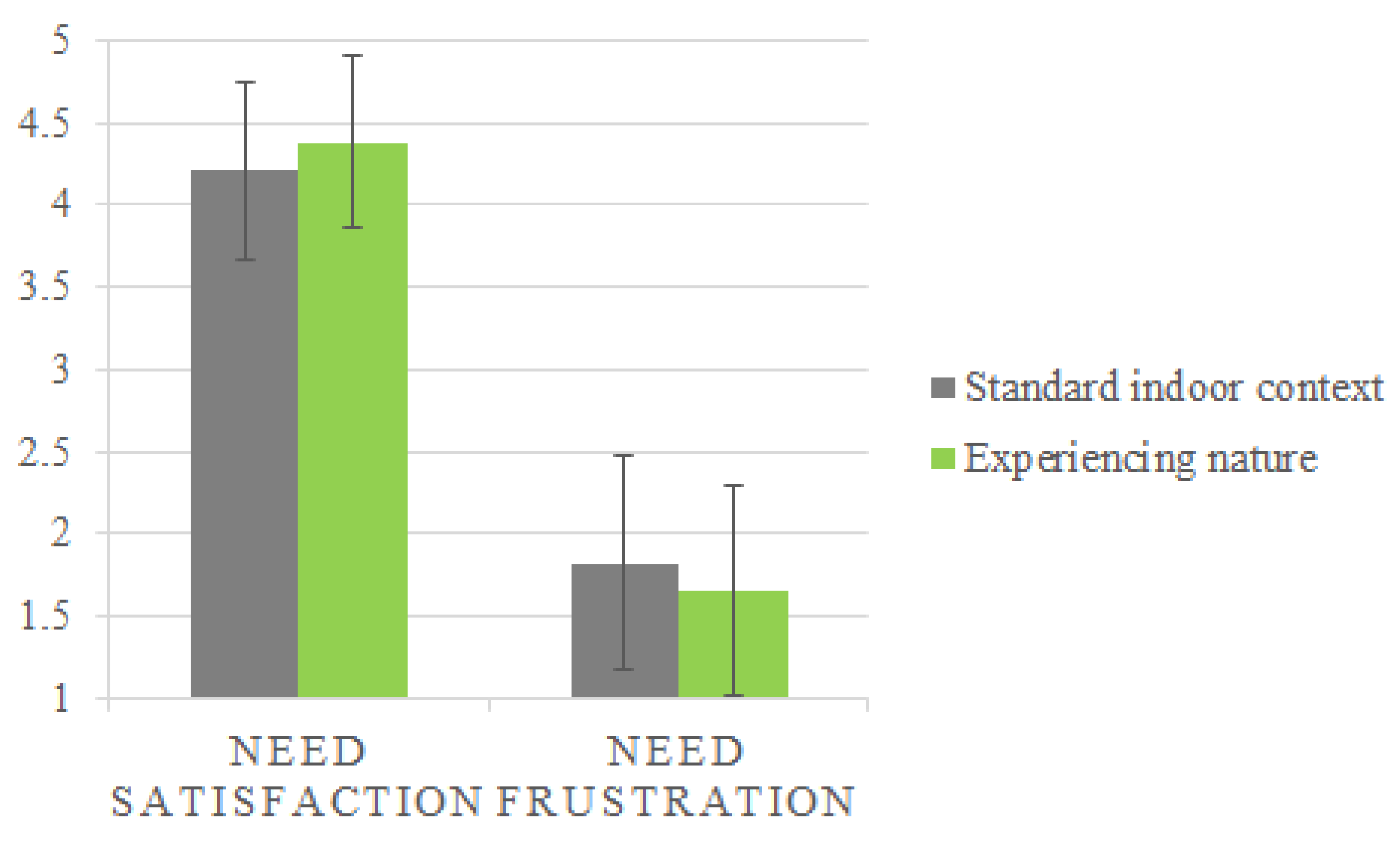

2.6.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

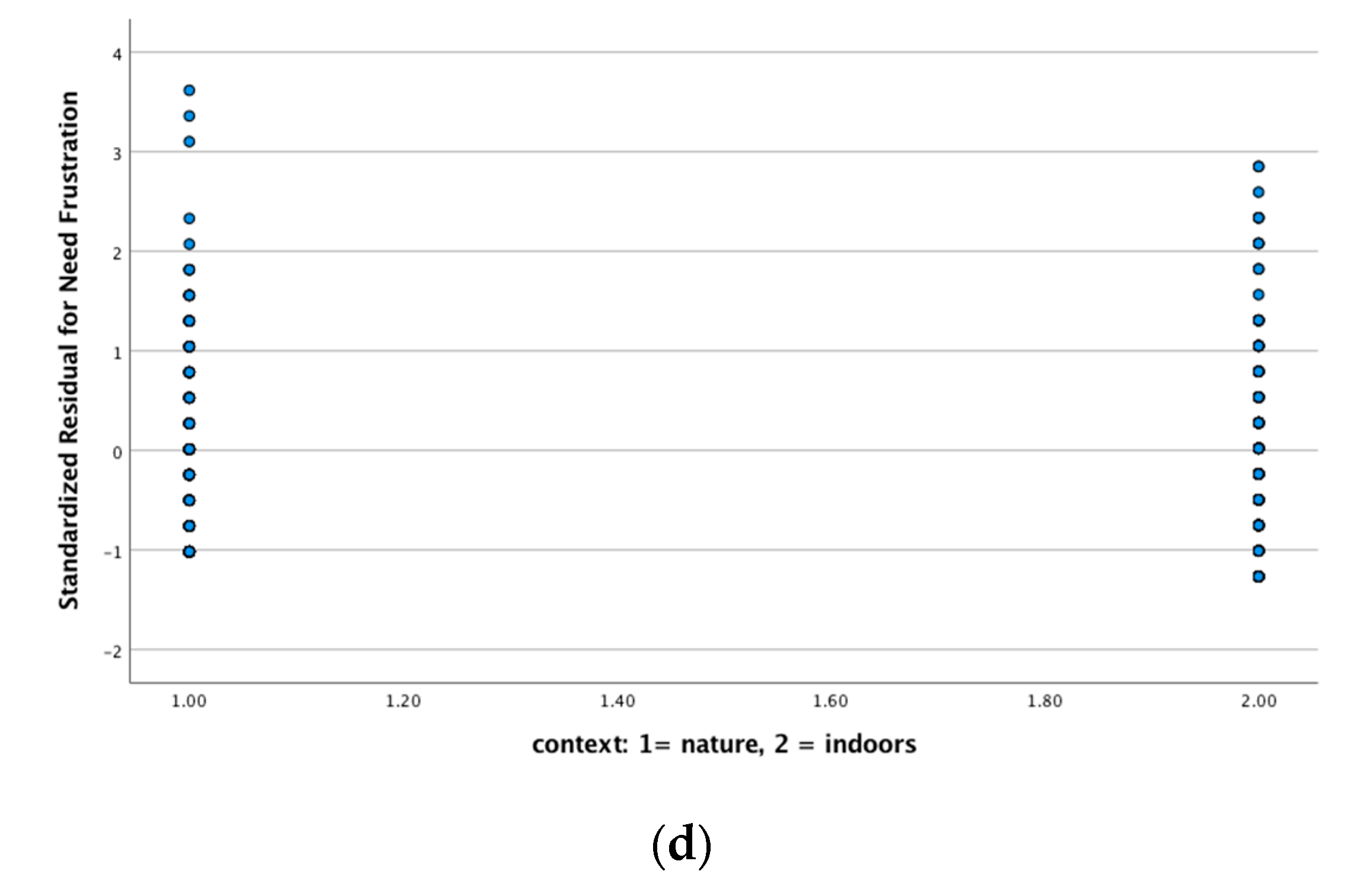

3.1. Participant Flow

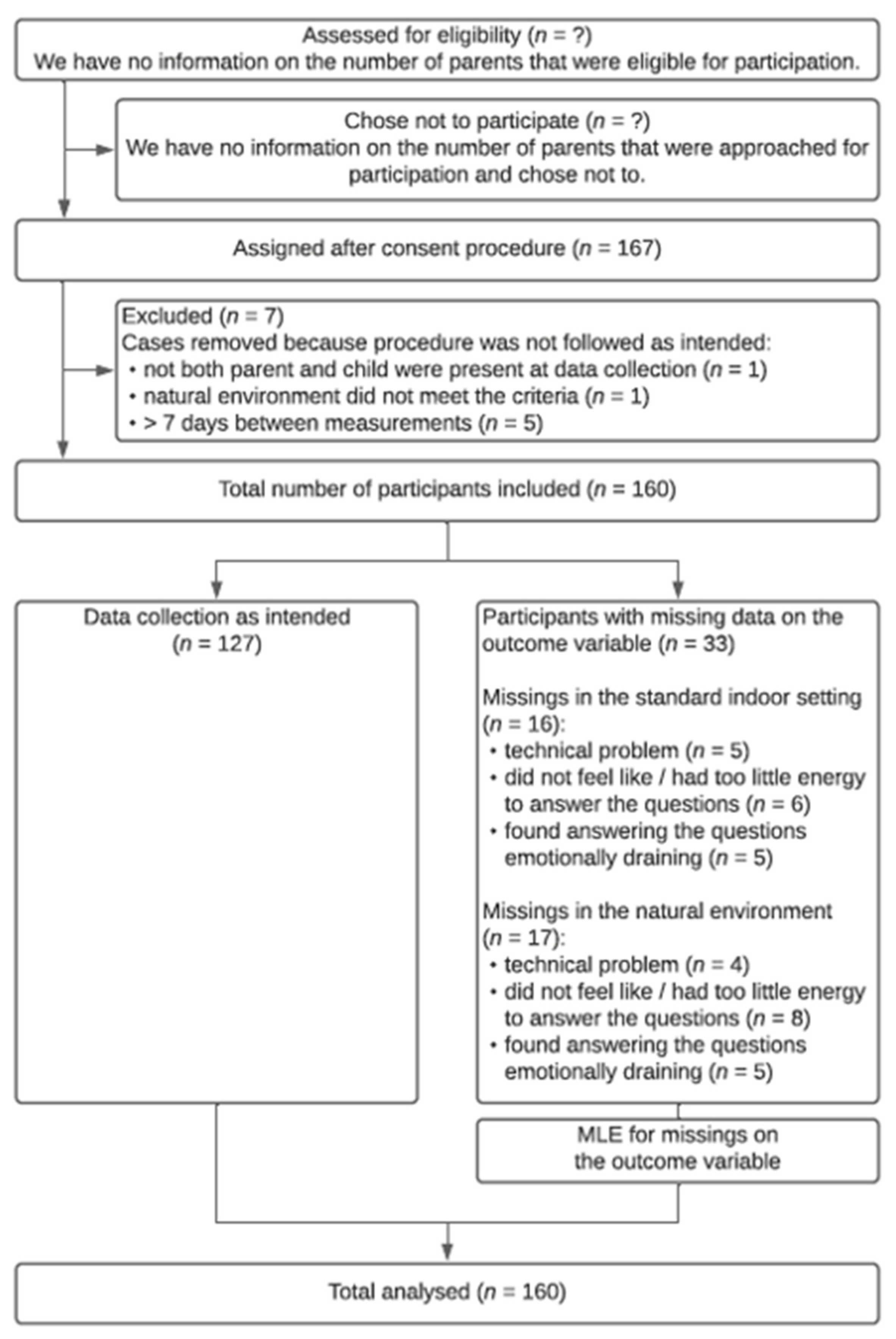

3.2. Associations between Experiencing Nature and Parental Self-Determination

4. Discussion

Sources of Potential Bias

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Environment | N Cases |

|---|---|

| Garden on the shelter property | 48 |

| Neighborhood green | 35 |

| Children’s farm | 24 |

| Park | 22 |

| Indoor nature (e.g., visiting pets in the shelter living space, an interior garden) | 11 |

| Natural playground | 10 |

| Forest | 9 |

| Beach | 1 |

| Effect Modifiers Tested | Need Satisfaction | Need Frustration | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | 95% CI | Sig. | B (SE) | 95% CI | Sig. | |

| Standard indoor environment (Ref) | ||||||

| Experiencing nature | 0.12 (0.15) | −0.18–0.42 | 0.42 | −0.17 (0.19) | −0.55–0.21 | 0.38 |

| Sequence effect | 0.23 (0.16) | −0.1–0.56 | 0.17 | −0.015 (0.21) | −0.43–0.4 | 0.94 |

| Sequence effect interaction term | −0.04 (0.09) | −0.22–0.14 | 0.68 | 0.01 (0.12) | −0.22–0.24 | 0.94 |

| Standard indoor environment (Ref) | ||||||

| Experiencing nature | 0.16 (0.11) | −0.07–0.38 | 0.16 | −0.13 (0.15) | −0.42–0.15 | 0.36 |

| Type of shelter | 0.12 (0.13) | −0.13–0.37 | 0.34 | −0.15 (0.17) | −0.47–0.18 | 0.38 |

| Type of shelter interaction term | −0.02 (0.07) | −0.16–0.12 | 0.82 | 0.03 (0.09) | −0.15–0.21 | 0.72 |

| Standard indoor environment (Ref) | ||||||

| Experiencing nature | 0.36 (0.09) | 0.18–0.54 | 0.00 | −0.42 (0.12) | −0.65–−0.19 | 0.00 |

| Age of the child | −0.08 (0.02) | −0.13–−0.03 | 0.00 | 0.09 (0.03) | 0.03–0.15 | 0.00 |

| Age of the child interaction term | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.01–0.07 | 0.01 * | −0.04 (0.02) | −0.08–−0.01 | 0.02 * |

| Standard indoor environment (Ref) | ||||||

| Experiencing nature | 0.09 (0.16) | −0.24–0.41 | 0.6 | −0.48 (0.24) | −0.95–−0.01 | 0.05 |

| The parent’s connectedness to nature | 0.14 (0.07) | 0.01–0.28 | 0.03 | −0.23 (0.09) | −0.2–0.16 | 0.79 |

| The parent’s connectedness to nature interaction term | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.1–0.05 | 0.51 | −0.06 (0.05) | −0.16–0.05 | 0.29 |

Appendix B

References

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brenning, K.; Soenens, B.; Mabbe, E.; Vansteenkiste, M. Ups and downs in the joy of motherhood: Maternal well-being as a function of psychological needs, personality, and infant temperament. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 20, 229–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, L.; Guay, F.; Senécal, C.; Pierce, T. Women’s depressive symptoms during the transition to motherhood: The role of competence, relatedness, and autonomy. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 1145–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jungert, T.; Landry, R.; Joussemet, M.; Mageau, G.; Gingras, I.; Koestner, R. Autonomous and controlled motivation for parenting: Associations with parent and child outcomes. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 1932–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross-Plourde, M.; Basque, D. Motivation to Become a Parent and Parental Satisfaction: The Mediating Effect of Psychological Needs Satisfaction. J. Fam. Issues 2019, 40, 1255–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenning, K.; Soenens, B. A Self-Determination Theory Perspective on Postpartum Depressive Symptoms and Early Parenting Behaviors. J. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 73, 1729–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabbe, E.; Soenens, B.; Vansteenkiste, M.; van der Kaap-Deeder, J.; Mouratidis, A. Day-to-day variation in autonomy-supportive and psychologically controlling parenting: The role of parents’ daily experiences of need satisfaction and need frustration. Parenting 2018, 18, 86–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pable, J. The homeless shelter family experience: Examining the influence of physical living conditions on perceptions of internal control, crowding, privacy, and related issues. J. Inter. Des. 2012, 37, 9–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvestre, J.; Kerman, N.; Polillo, A.; Lee, C.M.; Aubry, T.; Czechowski, K. A qualitative study of the pathways into and impacts of family homelessness. J. Fam. Issues 2018, 39, 2265–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, C.; Goodman, L. Living with and within the rules of domestic violence shelters: A qualitative exploration of residents’ experiences. Violence Against Women 2015, 21, 1481–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, E.R.; Vincent, A.; Shin, Y. Parenting and child experiences in shelter: A qualitative study exploring the effect of homelessness on the parent–child relationship. Child. Fam. Soc. Work 2018, 23, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayberry, L.S.; Shinn, M.; Benton, J.G.; Wise, J. Families experiencing housing instability: The effects of housing programs on family routines and rituals. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2014, 84, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azim, K.A.; MacGillivray, L.; Heise, D. Mothering in the margin: A narrative inquiry of women with children in a homeless shelter. J. Soc. Distress Homeless 2019, 28, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, C.; McGowan, J.; Michelson, D. How does homelessness affect parenting behaviour? A systematic critical review and thematic synthesis of qualitative research. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 21, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WAVE. WAVE COUNTRY REPORT 2019: The Situation of Women’s Specialist Support. Services in Europe; Women against Violence Europe: Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jonker, I.E.; Sijbrandij, M.; Wolf, J.R. Toward needs profiles of shelter-based abused women: Latent class approach. Psychol. Women Q. 2012, 36, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, E.; Lane, S.; Menard, A. Meeting Survivors’ Needs: A Multi-State Study of Domestic Violence Shelter Experiences; School of Social Work, University of Connecticut Hartford: Hartford, CT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jonker, I.E.; Jansen, C.C.; Christians, M.G.; Wolf, J.R. Appropriate care for shelter-based abused women: Concept mapping with Dutch clients and professionals. Violence Against Women 2014, 20, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haskett, M.E.; Loehman, J.; Burkhart, K. Parenting interventions in shelter settings: A qualitative systematic review of the literature. Child. Fam. Soc. Work 2016, 21, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabbe, L.; Ball, J.; Goldstein, A. Gardening for the mental well-being of homeless women. J. Holist. Nurs. 2013, 31, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reizvikh, D.D. How Women from Domestic Violence Situations Experience Informal Nature Therapy as Part of Their Trauma Healing Journey; University of Lethbridge, Faculty of Education: Lethbridge, AB, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Renzetti, C.M.; Follingstad, D.R.; Fleet, D. From blue to green: The development and implementation of a horticultural therapy program for residents of a battered women’s shelter. Violence Vict. 2015, 30, 676–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.; Clacherty, G. Shaping new spaces: An alternative approach to healing in current shelter interventions for vulnerable women in Johannesburg. In Healing and Change in the City of Gold; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 31–58. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, E.; Maas, J.; Schuengel, C.; Hovinga, D. Making women’s shelters more conducive to family life: Professionals’ exploration of the benefits of nature. Child. Geogr. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception: Classic Edition; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, E.M.; Davies, P.T.; Campbell, S.B. Developmental Psychopathology and Family Process: Theory, Research, and Clinical Implications; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cleary, A.; Fielding, K.S.; Bell, S.L.; Murray, Z.; Roiko, A. Exploring potential mechanisms involved in the relationship between eudaimonic wellbeing and nature connection. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2017, 158, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Beyers, W.; Boone, L.; Deci, E.L.; Van der Kaap-Deeder, J.; Duriez, B.; Lens, W.; Matos, L.; Mouratidis, A. Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motiv. Emot. 2015, 39, 216–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W. Inclusion with nature: The psychology of human-nature relations. In Psychology of Sustainable Development; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2002; pp. 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, C.; Czellar, S. The extended inclusion of nature in self scale. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 47, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.H.; Kwok, O.-m. Examining the rule of thumb of not using multilevel modeling: The “design effect smaller than two” rule. J. Exp. Educ. 2015, 83, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feingold, A. Confidence interval estimation for standardized effect sizes in multilevel and latent growth modeling. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 83, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntoumanis, N.; Ng, J.Y.; Prestwich, A.; Quested, E.; Hancox, J.E.; Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C.; Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M.; Lonsdale, C.; Williams, G.C. A meta-analysis of self-determination theory-informed intervention studies in the health domain: Effects on motivation, health behavior, physical, and psychological health. Health Psychol. Rev. 2020, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razani, N.; Morshed, S.; Kohn, M.A.; Wells, N.M.; Thompson, D.; Alqassari, M.; Agodi, A.; Rutherford, G.W. Effect of park prescriptions with and without group visits to parks on stress reduction in low-income parents: SHINE randomized trial. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, H.; Van Lissa, C.; Hagedoorn, P.; Kellar, I.; Helbich, M. The effect of short-term exposure to the natural environment on depressive mood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Res. 2019, 177, 108606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, E.H.; Van der Meulen, L.; Wichers, M.; Jeronimus, B.F. A primrose path? Moderating effects of age and gender in the association between green space and mental health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, Å.O.; Knez, I.; Gunnarsson, B.; Hedblom, M. The effects of naturalness, gender, and age on how urban green space is perceived and used. Urban. For. Urban. Green. 2016, 18, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameroff, A. The Transactional Model; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McMahan, E.A.; Estes, D. The effect of contact with natural environments on positive and negative affect: A meta-analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2015, 10, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, M.; van Poppel, M.; van Kamp, I.; Andrusaityte, S.; Balseviciene, B.; Cirach, M.; Danileviciute, A.; Ellis, N.; Hurst, G.; Masterson, D. Visiting green space is associated with mental health and vitality: A cross-sectional study in four european cities. Health Place 2016, 38, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyer, K.M.; Kaltenbach, A.; Szabo, A.; Bogar, S.; Nieto, F.J.; Malecki, K.M. Exposure to neighborhood green space and mental health: Evidence from the survey of the health of Wisconsin. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 3453–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norðdahl, K.; Einarsdóttir, J. Children’s views and preferences regarding their outdoor environment. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2015, 15, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowdell, K.; Gray, T.; Malone, K. Nature and its influence on children’s outdoor play. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2011, 15, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, S.; Maudsley, M. Play, Naturally: A Review of Children’s Natural Play; Play England: Londen, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tyrväinen, L.; Ojala, A.; Korpela, K.; Lanki, T.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kagawa, T. The influence of urban green environments on stress relief measures: A field experiment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballew, M.T.; Omoto, A.M. Absorption: How nature experiences promote awe and other positive emotions. Ecopsychology 2018, 10, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohly, H.; White, M.P.; Wheeler, B.W.; Bethel, A.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Nikolaou, V.; Garside, R. Attention Restoration Theory: A systematic review of the attention restoration potential of exposure to natural environments. J. Toxicol. Environ. HealthPart. B 2016, 19, 305–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KNMI. Royal Meteorological Institute of The Netherlands. Available online: https://www.knmi.nl/nederland-nu/klimatologie/maand-en-seizoensoverzichten (accessed on 3 November 2020).

- Connolly, M. Some like it mild and not too wet: The influence of weather on subjective well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2013, 14, 457–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Catalano, R.; Ong, M. Cold summer weather, constrained restoration, and the use of antidepressants in Sweden. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, A.; Grahn, P. Outdoor environments in healthcare settings: A quality evaluation tool for use in designing healthcare gardens. Urban. For. Urban. Green. 2014, 13, 878–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lygum, V.L.; Poulsen, D.V.; Djernis, D.; Djernis, H.G.; Sidenius, U.; Stigsdotter, U.K. Post-occupancy evaluation of a crisis shelter garden and application of findings through the use of a participatory design process. Herd: Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2019, 12, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Memari, S.; Pazhouhanfar, M.; Nourtaghani, A. Relationship between perceived sensory dimensions and stress restoration in care settings. Urban. For. Urban. Green. 2017, 26, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N (%) | Mean (SD) | Range | Missing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shelter type | ||||

| -Women’s shelter | 112 (70%) | |||

| -Shelter for homeless families | 29 (18%) | |||

| -Combined women’s/homeless shelter | 19 (12%) | |||

| Age of parent | 32 (6.9) | 19–65 | 26 (16%) | |

| Gender of parent | 10 (6%) | |||

| -Female | 145 (91%) | |||

| -Male | 1 (<1%) | |||

| -X (third gender or no gender) | 4 (3%) | |||

| Parent’s nature connectedness | 4.12 (1.6) | 1–7 | 95 (59%) | |

| Child’s age | 5.28 (3.6) | 0–16 | 37 (23%) |

| Measurement | Context | B (SE) | 95% CI | d(95% CI) |

| Need satisfaction | ||||

| Standard indoor context (ref) | ||||

| Experiencing nature | 0.18 (0.05) | (0.09–0.27) *** | 0.28 (0.14–0.43) | |

| Need frustration | ||||

| Standard indoor context (ref) | ||||

| Experiencing nature | −0.18 (0.06) | −0.3–−0.07) ** | −0.24 (−0.4–−0.09) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peters, E.; Maas, J.; Hovinga, D.; Van den Bogerd, N.; Schuengel, C. Experiencing Nature to Satisfy Basic Psychological Needs in Parenting: A Quasi-Experiment in Family Shelters. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8657. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228657

Peters E, Maas J, Hovinga D, Van den Bogerd N, Schuengel C. Experiencing Nature to Satisfy Basic Psychological Needs in Parenting: A Quasi-Experiment in Family Shelters. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(22):8657. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228657

Chicago/Turabian StylePeters, Elise, Jolanda Maas, Dieuwke Hovinga, Nicole Van den Bogerd, and Carlo Schuengel. 2020. "Experiencing Nature to Satisfy Basic Psychological Needs in Parenting: A Quasi-Experiment in Family Shelters" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 22: 8657. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228657

APA StylePeters, E., Maas, J., Hovinga, D., Van den Bogerd, N., & Schuengel, C. (2020). Experiencing Nature to Satisfy Basic Psychological Needs in Parenting: A Quasi-Experiment in Family Shelters. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8657. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228657