Global Mental Health and Services for Migrants in Primary Care Settings in High-Income Countries: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol

2.2. Research Question

2.3. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.4. Eligibility Criteria

2.5. Study Selection Process

2.6. Data Extraction

2.7. Methodological Quality Appraisal

2.8. Data Summary and Synthesis

3. Results

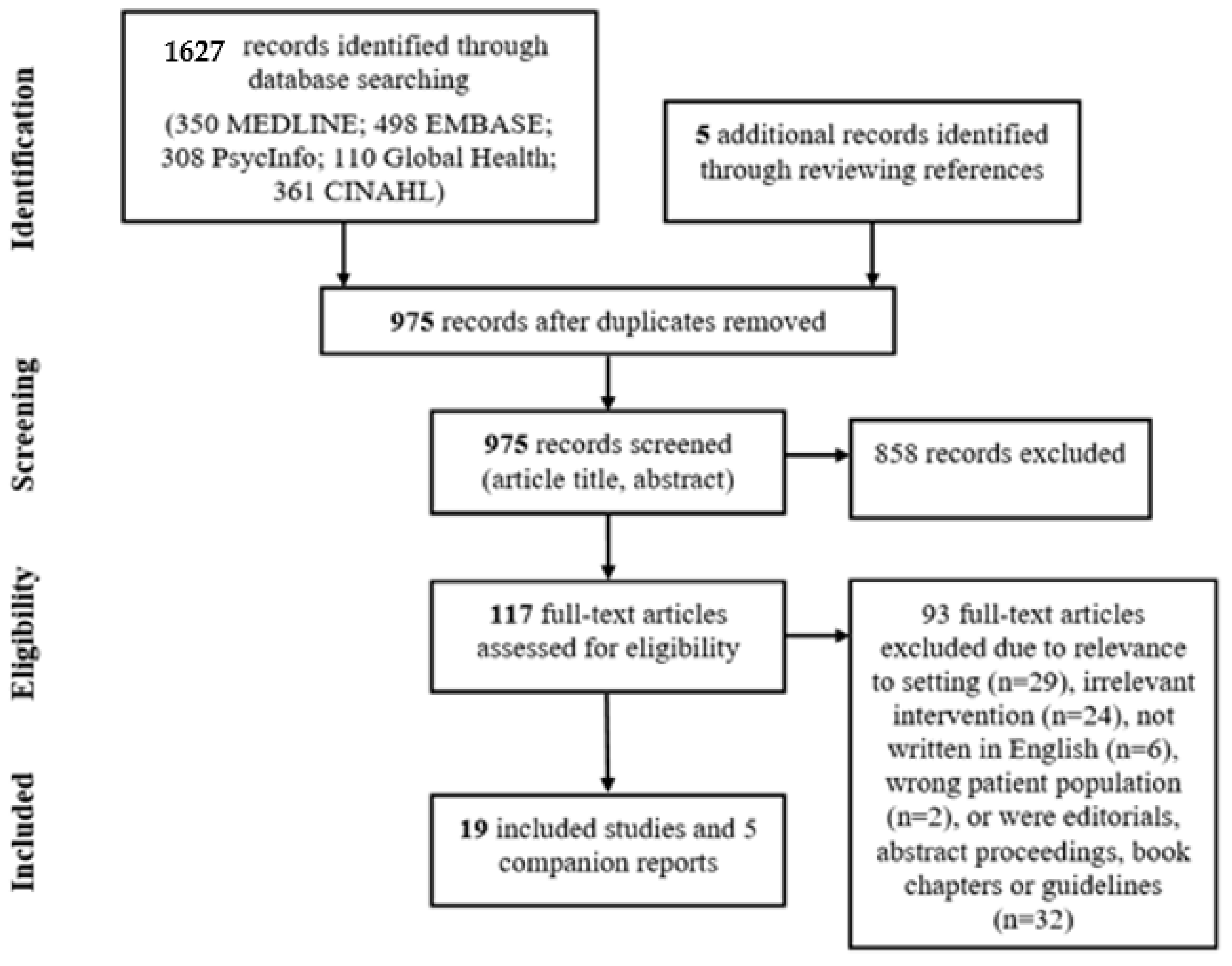

3.1. Literature Search

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Participant Characteristics

3.4. Approach to Care

3.5. Professionals Involved and Mental Health Services

3.6. Interventions and Impact Characteristics

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations of this Scoping Review

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Steel, Z.; Marnane, C.; Iranpour, C.; Chey, T.; Jackson, J.W.; Patel, V.; Silove, D. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 43, 476–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathers, C.D.; Loncar, D. Projections of Global Mortality and Burden of Disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006, 3, e442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for Europe. Health Promotion for Improved Refugee and Migrant Health; Technical Guidance; WHO: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018; Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/388363/tc-health-promotion-eng.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). Migration Data Portal—Estimated Number of Refugees at Mid-Year 2019. 2019. Available online: https://migrationdataportal.org/data?i=stock_refug_abs_&t=2019 (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). UNHCR Projected Global Resettlement Needs 2020. 2019. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/protection/resettlement/5d1384047/projected-global-resettlement-needs-2020.html (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- UNHCR. Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2019; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/5ee200e37.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Lindert, J.; Von Ehrenstein, O.S.; Priebe, S.; Mielck, A.; Brähler, E. Depression and anxiety in labor migrants and refugees—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norredam, M.; Garcia-Lopez, A.; Keiding, N.; Krasnik, A. Risk of mental disorders in refugees and native Danes: A register-based retrospective cohort study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2009, 44, 1023–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steel, Z.; Chey, T.; Silove, D.; Marnane, C.; Bryant, R.A.; Van Ommeren, M. Association of Torture and Other Potentially Traumatic Events With Mental Health Outcomes Among Populations Exposed to Mass Conflict and Displacement: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 2009, 302, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, J. Sexual and gender-based violence against refugee women: A hidden aspect of the refugee crisis. Reprod. Health Matters 2016, 24, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momartin, S.; Steel, Z.; Coello, M.; Aroche, J.; Silove, D.M.; Brooks, R. A comparison of the mental health of refugees with temporary versus permanent protection visas. Med. J. Aust. 2006, 185, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.; Haslam, N. Predisplacement and Postdisplacement Factors Associated with Mental Health of Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons: A Meta-analysis. JAMA 2005, 294, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, J.; Codony, M.; Kovess, V.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Katz, S.J.; Haro, J.M.; De Girolamo, G.; De Graaf, R.; Demyttenaere, K.; Vilagut, G.; et al. Population level of unmet need for mental healthcare in Europe. Br. J. Psychiatry 2007, 190, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demyttenaere, K.; Bruffaerts, R.; Posada-Villa, J.; Gasquet, I.; Kovess, V.; Lepine, J.P.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Bernert, S.; De Girolamo, G.; Morosini, P.; et al. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA 2004, 291, 2581–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.W.; Kazanjian, A. Rate of Mental Health Service Utilization by Chinese Immigrants in British Columbia. Can. J. Public Health 2005, 96, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenta, H.; Hyman, I.; Noh, S. Mental health service utilization by Ethiopian immigrants and refugees in Toronto. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2006, 194, 925–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.J.; Wong, F.Y.; Ronzio, C.R.; Yu, S.M. Depressive Symptomatology and Mental Health Help-Seeking Patterns of U.S.- and Foreign-Born Mothers. Matern. Child Health J. 2007, 11, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colucci, E.; Szwarc, J.; Minas, H.; Paxton, G.; Guerra, C. The utilisation of mental health services by children and young people from a refugee background: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Cult. Ment. Health 2014, 7, 86–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.J.; Wieling, E.; Simmelink-McCleary, J.; Becher, E. Beyond Stigma: Barriers to Discussing Mental Health in Refugee Populations. J. Loss Trauma 2015, 20, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, R.; Kirmayer, L.J.; Groleau, D. Understanding Immigrants’ Reluctance to Use Mental Health Services: A Qualitative Study from Montreal. Can. J. Psychiatry 2006, 51, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.C.; Marshall, G.N.; Schell, T.L.; Elliott, M.N.; Hambarsoomians, K.; Chun, C.-A.; Berthold, S.M. Barriers to mental health care utilization for U.S. Cambodian refugees. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 74, 1116–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eytan, A.; Bischoff, A.; Rrustemi, I.; Durieux, S.; Loutan, L.; Gilbert, M.; Bovier, P.A. Screening of mental disorders in asylum-seekers from Kosovo. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2002, 36, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, R. Primary health care for refugees and asylum seekers: A review of the literature and a framework for services. Public Health 2006, 120, 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmayer, L.J.; Groleau, D.; Guzder, J.; Blake, C.; Jarvis, E. Cultural consultation: A model of mental health service for multicultural societies. Can. J. Psychiatry Rev. Can. Psychiatr. 2003, 48, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aery, A.; McKenzie, K. Primary Care Utilization Trajectories for Immigrants and Refugees in Ontario Compared with Long-Term Residents; Wellesley Institute: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization; World Organization of Family Doctors. Integrating Mental Health into Primary Care: A Global Perspective; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland; Wonca: Singapore, 2008; ISBN 978-92-4-156368-0. [Google Scholar]

- Blount, A. An Introduction to Integrated Primary Care. In Integrated Primary Care: The Future of Medical and Mental Health Collaboration; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-393-70253-8. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, W.; McDaniel, S.; Baird, M. Five Levels of Primary Care/Behavioral Healthcare Collaboration. Behav. Healthc. Tomorrow 1996, 5, 25–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blount, A. Integrated Primary Care: Organizing the Evidence. Fam. Syst. Health 2003, 21, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.; Hewson, D.; Munger, R.; Wade, T. Evolving Models of Behavioral Health Integration in Primary Care; Milbank Memorial Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-887748-73-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltman, S.; Hurtado de Mendoza, A.; Gonzales, F.A.; Serrano, A. Preferences for trauma-related mental health services among Latina immigrants from Central America, South America, and Mexico. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2014, 6, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.D.; Popper, S.T.; Rodwell, T.C.; Brodine, S.K.; Brouwer, K.C. Healthcare Barriers of Refugees Post-resettlement. J. Community Health 2009, 34, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruner, D.; Magwood, O.; Bair, L.; Duff, L.; Adel, S.; Pottie, K. Understanding Supporting and Hindering Factors in Community-Based Psychotherapy for Refugees: A Realist-Informed Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abas, M.A.; Broadhead, J.C. Depression and anxiety among women in an urban setting in Zimbabwe. Psychol. Med. 1997, 27, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swinkels, H.; Pottie, K.; Tugwell, P.; Rashid, M.; Narasiah, L. Development of guidelines for recently arrived immigrants and refugees to Canada: Delphi consensus on selecting preventable and treatable conditions. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2011, 183, E928–E932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, M.; Kane, R.L.; McAlpine, D.; Kathol, R.; Fu, S.S.; Hagedorn, H.; Wilt, T. Does Integrated Care Improve Treatment for Depression?: A Systematic Review. J. Ambul. Care Manag. 2011, 34, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cape, J.; Whittington, C.; Buszewicz, M.; Wallace, P.; Underwood, L. Brief psychological therapies for anxiety and depression in primary care: Meta-analysis and meta-regression. BMC Med. 2010, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekers, D.; Murphy, R.; Archer, J.; Ebenezer, C.; Kemp, D.; Gilbody, S. Nurse-delivered collaborative care for depression and long-term physical conditions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 149, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbody, S.; Bower, P.; Fletcher, J.; Richards, D.; Sutton, A.J. Collaborative Care for Depression: A Cumulative Meta-analysis and Review of Longer-term Outcomes. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 2314–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muntingh, A.D.; Van der Feltz-Cornelis, C.M.; Van Marwijk, H.W.; Spinhoven, P.; Van Balkom, A.J. Collaborative care for anxiety disorders in primary care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Fam. Pract. 2016, 17, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNHCR. Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. Asylum-Seekers. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/asylum-seekers.html (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- United Nations. Programme of Action: Adopted at the International Conference on Population and Development, Cairo; UNFPA: New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-89714-696-8. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Future of Primary Care. Defining Primary Care. In Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era; Donaldson, M.S., Yordy, K.D., Lohr, K.N., Vanselow, N.A., Eds.; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence Systematic Review Software; Covidence: Melbourne, Australia, 2020; Available online: www.covidence.org (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Ahmad, F.; Lou, W.; Shakya, Y.; Ginsburg, L.; Ng, P.T.; Rashid, M.; Dinca-Panaitescu, S.; Ledwos, C.; McKenzie, K. Preconsult interactive computer-assisted client assessment survey for common mental disorders in a community health centre: A randomized controlled trial. CMAJ Open 2017, 5, E190–E197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asgary, R.G.; Metalios, E.E.; Smith, C.L.; Paccione, G.A. Evaluating asylum seekers/torture survivors in urban primary care: A collaborative approach at the Bronx Human Rights Clinic. Health Hum. Rights 2006, 9, 164–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertelsen, N.S.; Selden, E.; Krass, P.; Keatley, E.S.; Keller, A. Primary Care Screening Methods and Outcomes for Asylum Seekers in New York City. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2018, 20, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosson, R.; Williams, M.; Frazier, V.; Lippman, S.; Carrico, R.; Kanter, J.; Pena, A.; Mier-Chairez, J.; Ramirez, J. Addressing refugee mental health needs: From concept to implementation. Behav. Ther. 2017, 40, 110–112. [Google Scholar]

- Dalgaard, N.T.; Thøgersen, M.H.; Montgomery, E. Interdisciplinary treatment of family violence in traumatized refugee families. Int. J. Migr. Health Soc. Care 2020, 16, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, M.; Fennig, S.; Lurie, I. Identification of Emotional Distress Among Asylum Seekers and Migrant Workers by Primary Care Physicians: A Brief Report. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2015, 52, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Furler, J.; Kokanovic, R.; Dowrick, C.; Newton, D.; Gunn, J.; May, C. Managing depression among ethnic communities: A qualitative study. Ann. Fam. Med. 2010, 8, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, N.K.; Norredam, M.; Priebe, S.; Krasnik, A. How do general practitioners experience providing care to refugees with mental health problems? A qualitative study from Denmark. BMC Fam. Pract. 2013, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, J.D.; Macfarlane, A.; Avalos, G.E.; Cantillon, P.; Murphy, A.W. A survey of asylum seekers’ general practice service utilisation and morbidity patterns. Ir. Med. J. 2007, 100, 461–464. [Google Scholar]

- Njeru, J.W.; DeJesus, R.S.; Sauver, J.S.; Rutten, L.J.; Jacobson, D.J.; Wilson, P.; Wieland, M.L. Utilization of a mental health collaborative care model among patients who require interpreter services. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2016, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northwood, A.K.; Vukovich, M.M.; Beckman, A.; Walter, J.P.; Josiah, N.; Hudak, L.; O’Donnell Burrows, K.; Letts, J.P.; Danner, C.C. Intensive psychotherapy and case management for Karen refugees with major depression in primary care: A pragmatic randomized control trial. BMC Fam. Pract. 2020, 21, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polcher, K.; Calloway, S. Addressing the Need for Mental Health Screening of Newly Resettled Refugees: A Pilot Project. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2016, 7, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, C.; Measham, T.; Nadeau, L. Addressing trauma in collaborative mental health care for refugee children. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2013, 18, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarasinghe, K.; Fridlund, B.; Arvidsson, B. Primary health care nurses’ promotion of involuntary migrant families’ health. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2010, 57, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, A.M.; Jolles, D. Not Missing the Opportunity: Improving Depression Screening and Follow-Up in a Multicultural Community. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2019, 45, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorkin, D.H.; Rizzo, S.; Biegler, K.; Sim, S.E.; Nicholas, E.; Chandler, M.; Ngo-Metzger, Q.; Paigne, K.; Nguyen, D.V.; Mollica, R. Novel Health Information Technology to Aid Provider Recognition and Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Primary Care. Med. Care 2019, 57, S190–S196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weine, S.M.; Raina, D.; Zhubi, M.; Delesi, M.; Huseni, D.; Feetham, S.; Kulauzovic, Y.; Mermelstein, R.; Campbell, R.T.; Rolland, J.; et al. The TAFES multi-family group intervention for Kosovar refugees: A feasibility study. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2003, 191, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.C.; Solid, C.A.; Hodges, J.S.; Boehm, D.H. Does Integrated Care Affect Healthcare Utilization in Multi-problem Refugees? J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2015, 17, 1444–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Shakya, Y.; Ginsburg, L.; Lou, W.; Ng, P.T.; Rashid, M.; Ferrari, M.; Ledwos, C.; McKenzie, K. Burden of common mental disorders in a community health centre sample. Can. Fam. Physician 2016, 62, e758–e766. [Google Scholar]

- Esala, J.J.; Hudak, L.; Eaton, A.; Vukovich, M. Integrated behavioral health care for Karen refugees: A qualitative exploration of active ingredients. Int. J. Migr. Health Soc. Care 2018, 14, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M.; Ahmad, F.; Shakya, Y.; Ledwos, C.; McKenzie, K. Computer-assisted client assessment survey for mental health: Patient and health provider perspectives. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M.; Shakya, Y.; Ledwos, C.; McKenzie, K.; Ahmad, F. Patients’ Mental Health Journeys: A Qualitative Case Study with Interactive Computer-Assisted Client Assessment Survey (iCASS). J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2018, 20, 1173–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurie, I. Psychiatric Care in Restricted Conditions for Work Migrants, Refugees and Asylum Seekers: Experience of the Open Clinic for Work Migrants and Refugees, Israel 2006. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2009, 46, 172–181. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson, J.; Sonne, C.; Silove, D. From Pioneers to Scientists: Challenges in Establishing Evidence-Gathering Models in Torture and Trauma Mental Health Services for Refugees. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2014, 202, 630–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaranson, J.M.; Quiroga, J. Evaluating the services of torture rehabilitation programmes: History and recommendations. Torture 2011, 21, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Purkey, E.; Patel, R.; Phillips, S.P. Trauma-informed care. Can. Fam. Physician 2018, 64, 170–172. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- International Society for Social Pediatrics and Child Health (ISSOP). Budapest Declaration on the Rights, Health and Well-Being of Children and Youth on the Move; ISSOP: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Linton, J.M.; Green, A.; Pediatrics, C. on C. Providing Care for Children in Immigrant Families. Pediatrics 2019, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, B.L.; Kaltman, S.; Frank, L.; Glennie, M.; Subramanian, A.; Fritts-Wilson, M.; Chung, J. Primary care providers’ experiences with trauma patients: A qualitative study. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2011, 3, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.J.; O’Dougherty, M.; Mehta, E. Refugees’ perspectives on barriers to communication about trauma histories in primary care. Ment. Health Fam. Med. 2012, 9, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Green, B.L.; Saunders, P.A.; Power, E.; Dass-Brailsford, P.; Schelbert, K.B.; Giller, E.; Wissow, L.; Hurtado-de-Mendoza, A.; Mete, M. Trauma-Informed Medical Care: A CME Communication Training for Primary Care Providers. Fam. Med. 2015, 47, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Chambless, D.L.; Sanderson, W.C.; Shoham, V.; Johnson, S.B.; Pope, K.S.; Crits-Christoph, P.; Baker, M.; Johnson, B.; Woody, S.R.; Sue, S.; et al. An Update on Empirically Validated Therapies. Clin. Psychol. 1996, 49, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, J.; Tabish, H.; Welch, V.; Petticrew, M.; Pottie, K.; Clarke, M.; Evans, T.; Pardo Pardo, J.; Waters, E.; White, H.; et al. Applying an equity lens to interventions: Using PROGRESS ensures consideration of socially stratifying factors to illuminate inequities in health. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Refugee | “Someone who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion” [44] |

| Asylum seeker | “Someone whose request for sanctuary has yet to be processed” [45] | |

| Undocumented migrant | “Persons who do not fulfil the requirements established by the country of destination to enter, stay, or exercise an economic activity” [46] | |

| Concept | Mental health services: “Early identification of mental disorders, treatment of common mental disorders, management of stable psychiatric patients, referral to other levels where required, attention to the mental health needs of people with physical health problems, and mental health promotion and prevention” [26] | |

| Context | 1. Primary care setting: “The first level of care within the formal health system” [26] and is mostly led by family physicians, general practitioners, pediatricians, or nurse practitioners [47] | |

| 2. High-income countries: “Those with a Gross National Income (GNI) per capita of $12,376 or more” [48] | ||

| Author(s)/Year | Design | Setting | Participant Description | Care Approach | Professionals Involved | Mental Health Services and Intervention | Collaboration between Professionals | Intervention | Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asgary et al. 2006 | Retrospective chart review | A human rights clinic affiliated with a medical center (US) | Adult asylum seekers from multiple countries of origin | Cross-cultural care and communication; integrated care | PCPs, medical residents, interpreters | Screening, diagnosis, unspecified treatment | Medical residents screened, diagnosed, and treated patients, while precepted by the attending physicians. | N/A | N/A |

| Bertelsen et al. 2018 | Retrospective chart review | A program for survivors of torture affiliated with a medical center (US) | Adult asylum seekers from multiple countries of origin | Cross-cultural care and communication; co-located care | PCPs, nurses, mental health professionals (unspecified), trainees of mental health professionals, interpreters | Screening, diagnosis, pharmacotherapy, referral to community mental health services | Mental health professionals or their trainees screened, diagnosed, and referred patients to appropriate services. PCPs provided pharmacologic management. | N/A | N/A |

| Bosson et al. 2017 | Case report | A global health center affiliated with a university (US) | Refugee children, adults, and seniors from multiple countries of origin | Cross-cultural care and communication; integrated care; trauma-informed care | PCPs, APRNs, psychologists/psychotherapists, psychiatrists, social workers/case managers, trainees of mental health professionals, interpreters, global health navigators | Screening, diagnosis, psychotherapy (CBT, family and couple therapy), facilitation of support groups | Psychologists and PCPs screened and diagnosed patients, while psychologists and psychiatrists provided psychotherapy. Trainees of mental health professionals were also included to assess and treat patients. Global health navigators assisted with interpreting, advocacy, and connecting with local groups and agencies. | N/A | N/A |

| Dalgaard et al. 2019 | Qualitative | A treatment center for torture victims (Denmark) | Health care providers | Cross-cultural care and communication; integrated care | PCPs, psychologists/psychotherapists, social workers/case managers, interpreters, physiotherapists | Diagnosis, pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy (CBT, family and couple therapy, psychoeducation, somatic experiencing), referral to community mental health services, social work services, physiotherapy | PCPs, psychologists, social workers, and physiotherapists all initially assessed patients. Psychologists and physiotherapists provide psychotherapy, while GPs provide pharmacologic management and refer complex cases to psychiatrists. Physiotherapists provide individual physiotherapy. Social workers help families navigate the Danish system for social services. | N/A | N/A |

| Dick et al. 2015 Companion article: Lurie 2009 | Cross-sectional | A human rights clinic (Israel) | Adult and elderly refugees, asylum seekers, and undocumented migrants from multiple countries of origin | Cross-cultural care and communication; co-located care | PCPs, nurses, psychiatrists, interpreters, physiotherapist, dietitians, acupuncturists | Screening, diagnosis, pharmacotherapy | PCPs screened and diagnosed patients, while psychiatrists prescribed medications. | N/A | N/A |

| Schaeffer et al. 2019 | Quality improvement project | A community health center (US) | Health care providers | Cross-cultural care and communication; integrated care | PCPs, APRNs, social workers/case managers, interpreters | Screening, diagnosis, psychotherapy, referral to community mental health services, brief intervention | PCPs and APRNs screened, diagnosed, offered brief intervention (Option Grid), and referred patients to community mental health services. Clinical social workers provided psychotherapy. | Use of written standardized Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) screening tools in six languages, the Option Grid for clients who screen positive for depression, a “right care” tracking log for screen- positive clients, and team meetings to support capacity building. | The same community health center before the implementation of the quality improvement project. |

| Ahmad et al. 2017 Companion articles: Ahmad et al. 2016 Ferrari et al. 2016 Ferrari et al. 2018 | RCT | A community health center (Canada) | Adult refugees and asylum seekers from multiple countries of origin | Cross-cultural care and communication; integrated care | PCPs, APRNs, psychiatrists, social workers/case managers, interpreters | Technology-assisted screening, diagnosis, pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy | Research assistants screened patients for common mental disorders using an interactive survey on an iPad. PCPs diagnosed, prescribed medications, and referred patients to other mental health professionals. Social workers offered psychotherapy, while psychiatrists provided pharmacologic management. | An Interactive Computer-Assisted Client Assessment Survey (iCCAS) that is used to detect common mental disorders. | Care as usual with no health-risk assessments before the consultation |

| Furler et al. 2010 | Qualitative | A community health center and primary care clinics (Australia) | Health care providers | Cross-cultural care and communication | PCPs, interpreters | Diagnosis, pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy (family and couple therapy, unspecified individual counselling) | PCPs diagnosed, prescribed medications, and provided psychotherapy to patients. | N/A | N/A |

| Jensen et al. 2013 | Qualitative | Primary care clinics (Denmark) | Health care providers | Cross-cultural care and communication; coordinated care; trauma-informed care | PCPs, interpreters | Diagnosis, pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, referral to community mental health services | PCPs diagnosed, prescribed medications, provided psychotherapy, and referred patients to community mental health services. | N/A | N/A |

| Kirmayer et al. 2003 | Mixed methods (qualitative and quantitative methods) | A cultural consultation service affiliated with a hospital | Refugees and asylum seekers from multiple countries of origin | Cross-cultural care and communication; coordinated care | Medical residents, psychiatric nurses, psychologists/psychotherapists, psychiatrists, social workers/case managers, trainees of mental health professionals, interpreters, culture brokers, medical anthropologists | Diagnosis, pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy (CBT, family and couple therapy), provide recommendations to treatment | Mental health professionals diagnosed patients, provided pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, and recommendations to treatment. | N/A | N/A |

| Samarasinghe et al. 2010 | Qualitative | Primary health centers (Sweden) | Health care providers | Cross-cultural care and communication | APRNs | Health promotion | APRNs engaged in health promotion. | N/A | N/A |

| McMahon et al. 2007 | Retrospective chart review | Two primary care clinics (Ireland) | Asylum seekers (children and adults) from multiple countries of origin | Cross-cultural care and communication | PCPs | Diagnosis, pharmacotherapy | PCPs diagnosed patients, provided pharmacotherapy, and referred patients to other services. | N/A | Irish citizens |

| Njeru et al. 2016 | Retrospective cohort | Primary care clinics affiliated with a medical center (US) | Adult refugees | Cross-cultural care and communication; integrated care | PCPs, nurses, psychiatrists, interpreters | Screening, diagnosis, pharmacotherapy | Psychiatrists provided oversight, while PCPs screened, diagnosed, and prescribed medications. Nurses served as the care manager and interacted with patients through face-to-face and telephone visits. | Collaborative care management (CCM) model | N/A |

| Northwood et al. 2020 Companion article: Esala et al. 2018 | RCT | Two urban primary care clinics (US) | Adult refugees from East Asia and the Pacific | Cross-cultural care and communication; co-located care; trauma-informed care | PCPs, nurses, psychologists/psychotherapists, social workers/case managers, interpreters | Diagnosis, pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy (CBT, psychoeducation, motivational interviewing, NET), case management, social work services | PCPs diagnosed and prescribed medication. Psychotherapists offered psychotherapy, and case managers/social workers helped with case management and social work services. Psychotherapists and case managers did not write prescriptions; however, they flagged medical issues noted by participants for PCPs. | Intensive, coordinated psychotherapy and case management | Care as usual from PCPs (behavioral health referrals and/or brief onsite interventions) |

| Polcher et al. 2016 | Cohort | A community health clinic (US) | Adult refugees from multiple countries of origin | Cross-cultural care and communication; coordinated care | PCPs, nurses, interpreters, medical assistants | Screening, diagnosis, pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, referral to community mental health services | Interpreters and medical assistants screened patients, while nurses followed up and discussed the results of the screening with patients. PCPs diagnosed, prescribed medications, offered counselling, and referred patients to community mental health services when needed. | Mental health screening using the Refugee Health Screener–15 | N/A |

| Rousseau et al. 2013 | Case series | Community-based health and social services clinics (Canada) | Refugee children from multiple countries of origin | Cross-cultural care and communication; co-located care | PCPs, psychiatrists, social workers/case managers, mental health professionals (unspecified), school staff | Diagnosis, psychotherapy (humanistic therapies, psychoeducation) | The youth mental health team in the community-based health and social services clinics diagnosed and provided psychotherapy to patients, while the child psychiatry cultural consultants offered cultural consultation. | N/A | N/A |

| Sorkin et al. 2019 | RCT | Two community health centers (US) | Adult refugees from East Asia and the Pacific | Cross-cultural care and communication; integrated care; trauma-informed care | PCPs, medical residents | Technology-assisted screening, diagnosis, pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, referral to community mental health services | Research assistant screened patients for depression and PTSD using an iPad that administered the screening tools in patients’ preferred language. PCPs diagnosed patients, provided pharmacologic management and psychotherapy, and referred patients to community mental health services. | First, PCPs completed an online tutorial on how to provide culturally competent, trauma-informed mental health care to the Southeast Asian population. The second component involved screening all patients just before their appointment using an iPad that administered the screening tools. The third component involved giving PCPs access to evidence-based clinical algorithms and guidelines through a web-based mobile application. | Minimal intervention control condition |

| Weine et al. 2003 | Feasibility study | A community health organization (US) | Adult refugees from Europe and Central Asia | Cross-cultural care and communication; coordinated care | Lay workers, nurses, psychiatrists | Pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy (psychoeducation, support groups) | Lay workers are trained to provide family outreach and multi-family group sessions, while an outreach team of a psychiatrist and nurse from their partnering clinic provided psychotherapy or medications for refugees requesting or needing those services. | Family outreach and multi-family group sessions. | N/A |

| White et al. 2015 | Quasi-experimental retrospective | A Somali primary care clinic affiliated with a medical center (US) | Female refugees (adults and seniors) from Sub-Saharan Africa | Cross-cultural care and communication; co-located care; trauma-informed care | PCPs, psychologists/psychotherapists, interpreters | Diagnosis, pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, referral to community mental health services | PCPs provided a four-visit staged approach to trauma assessment in office, including diagnosis, pharmacologic management, and referral to psychologists, while psychologists provided psychotherapy. | Staged but flexible four-visit protocol for addressing physical and psychological complaints by the PCPs, trauma-informed psychotherapy provided by psychologists, as well as co-management of patients receiving physical and mental health services. | 2 post-hoc groups (therapy adherents and therapy non-adherents) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, J.; Jamani, S.; Benjamen, J.; Agbata, E.; Magwood, O.; Pottie, K. Global Mental Health and Services for Migrants in Primary Care Settings in High-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228627

Lu J, Jamani S, Benjamen J, Agbata E, Magwood O, Pottie K. Global Mental Health and Services for Migrants in Primary Care Settings in High-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(22):8627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228627

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Jia, Shabana Jamani, Joseph Benjamen, Eric Agbata, Olivia Magwood, and Kevin Pottie. 2020. "Global Mental Health and Services for Migrants in Primary Care Settings in High-Income Countries: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 22: 8627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228627

APA StyleLu, J., Jamani, S., Benjamen, J., Agbata, E., Magwood, O., & Pottie, K. (2020). Global Mental Health and Services for Migrants in Primary Care Settings in High-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228627