The Psychological Consequences of COVID-19 and Lockdown in the Spanish Population: An Exploratory Sequential Design

Abstract

1. Introduction

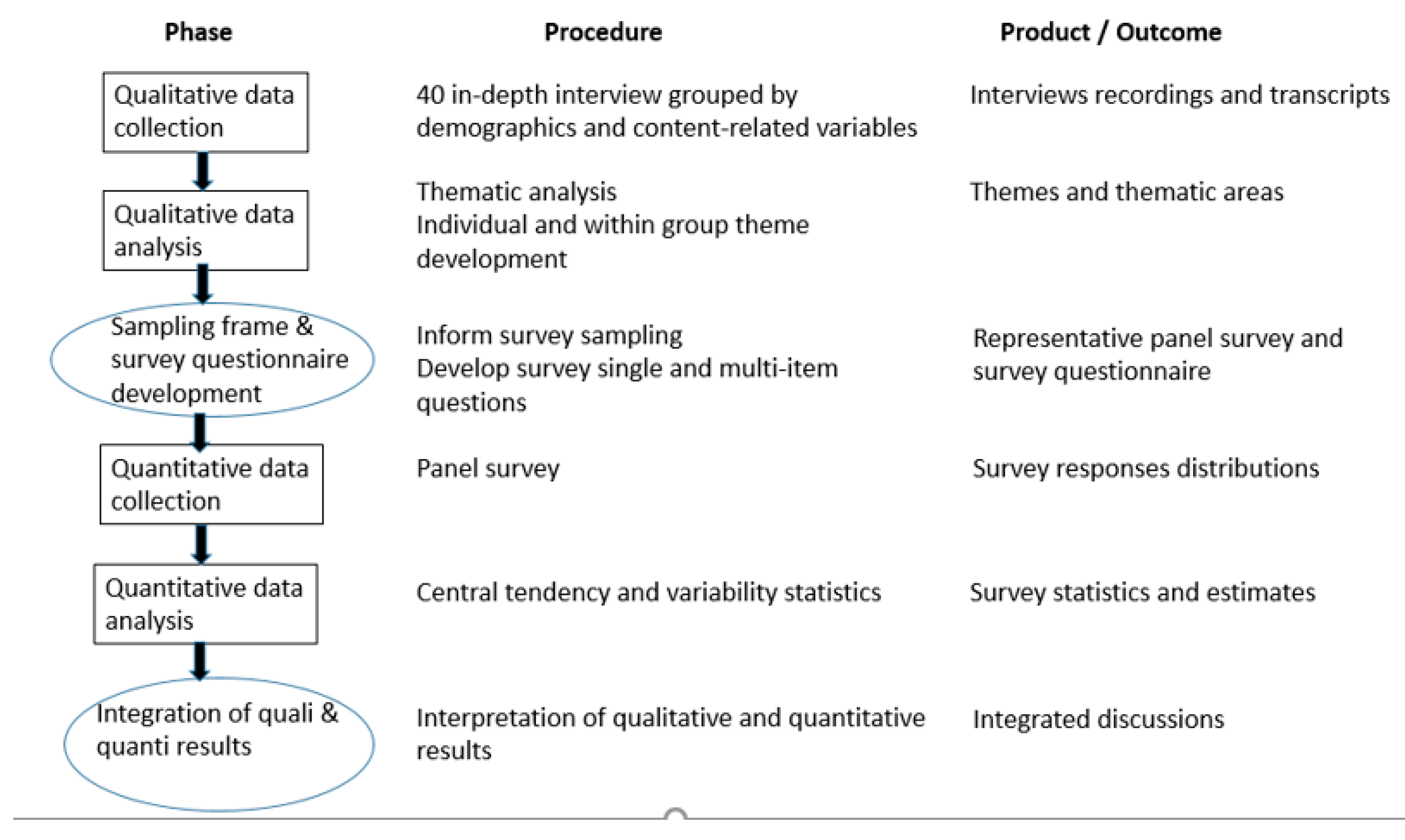

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Qualitative Phase

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Interview Protocol

2.1.3. Data Collection and Analysis

2.2. Quantitative Phase

2.2.1. Setting

2.2.2. Participants

2.2.3. Data Collection

2.2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Psychological Changes by Gender

“This is hard and here at home there have been days when one of my children has been truly down, despairing, and the tears start to fall.”(IN19_H_33)

“I’m more nervous, everything is mounting up, the children, the house, that my husband is out there. I’m scared.”(IN23_M_42)

3.2. Psychological Changes by Age

“I feel overwhelmed.”(IN01_M_22)

“Our exams have been suspended, they are going to be delayed and they haven’t told us when they will be and it feels uncertain since you don’t really know what is going to happen.”(IN18_F_30)

“I was very afraid; my children lost their father in November and I don’t think they are ready to lose their mother.”(IN35_F_60)

“The best... also the solidarity that everyone has demonstrated. Thinking about others and being more human in general, in our life, that remains and will remain, for those of us who have lived through this experience, it will remain...”(IN36_M_62)

3.3. Psychological Changes by Socioeconomic Level

“I am struggling a little at night, I wake up and I get a little panicked because I can’t see an easy solution to this.”(IN17_F_52)

“The work situation comes to mind, the uncertainty, when will it resume, whether it’s going to be the same...”(IN26_M_35)

“I’m worried that people will suffer.”(IN20_F_56)

“The volunteer work I do is delivering food: we go to the location they have, there are shopping trolleys, we fill them with purchases, people come and get the food.”(IN40_M_21).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawryluck, L.; Gold, W.L.; Robinson, S.; Pogorski, S.; Galea, S.; Styra, R. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 1206–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprang, G.; Silman, M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in parents and youth after health-related disasters. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2013, 7, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Fang, Z.; Hou, G.; Han, M.; Xu, X.; Dong, J.; Zheng, J. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 287, 112934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, L.; Ren, H.; Cao, R.; Hu, Y.; Qin, Z.; Li, C.; Mei, S. The effect of COVID-19 on youth mental health. Psychiatry Q. 2020, 91, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Zhang, F.; Wei, C.; Jia, Y.; Shang, Z.; Sun, L.; Wu, L.; Sun, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: Gender differences matter. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 287, 112921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; An, Y.; Tan, X.; Li, X. Mental health and its influencing factors among self-isolating ordinary citizens during the beginning epidemic of COVID-19. J. Loss Trauma 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, P.M.M.; Moreira, M.M.; de Oliveira, M.N.A.; Landim, J.M.M.; Neto, M.L.R. The psychiatric impact of the novel coronavirus outbreak. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 286, 112902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espada, J.P.; Orgilés, M.; Piqueras, J.A.; Morales, A. Las buenas prácticas en la atención psicológica infanto-juvenil ante el COVID-19 [Good practices in child and adolescent psychological care in the face of COVID-19]. Clin. Salud 2020, 31, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Shen, B.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Z.; Xie, B.; Xu, Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. Gen. Psychiatry 2020, 33, e100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, M.; Luo, S.; She, R.; Yu, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, S.; Ma, L.; Tao, F.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, J.; et al. Negative cognitive and psychological correlates of mandatory quarantine during the initial COVID-19 outbreak in China. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.X.; Wang, Y.; Rauch, A.; Wei, F. Unprecedented disruption of lives and work: Health, distress and life satisfaction of working adults in China one month into the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 112958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauri Korajlija, A.; Jokic-Begic, N. COVID-19: Concerns and behaviours in Croatia. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonzi, S.; La Torre, A.; Silverstein, M.W. The psychological impact of preexisting mental and physical health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Trauma 2020, 12, S236–S238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualano, M.R.; Lo Moro, G.; Voglino, G.; Bert, F.; Siliquini, R. Effects of Covid-19 on mental health and sleep disturbances in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, K.M.; Harris, C.; Drawve, G. Fear of COVID-19 and the mental health consequences in America. Psychol. Trauma 2020, 12, S17–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rey, R.; Garrido-Hernansaiz, H.; Collado, S. Psychological impact and associated factors during the initial stage of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic among the general population in Spain. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, E.; López-Romero, L.; Domínguez-Álvarez, B.; Villar, P.; Gómez-Fraguela, J.A. Testing the effects of COVID-19 confinement in Spanish children: The role of parents’ distress, emotional problems and specific parenting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandín, B.; Valiente, R.M.; García-Escalera, J.; Chorot, P. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: Negative and positive effects in Spanish people during the mandatory national quarantine. Rev. Psicopatol. Psicol. Clin. 2020, 25, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Guetterman, T.C.; Fetters, M.D.; Creswell, J.W. Integrating quantitative and qualitative results in health science mixed methods research through joint displays. Ann. Fam. Med. 2015, 13, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caleo, G.; Duncombe, J.; Jephcott, F.; Lokuge, K.; Mills, C.; Looijen, E.; Theoharaki, F.; Kremer, R.; Kleijer, K.; Squire, J.; et al. The factors affecting household transmission dynamics and community compliance with Ebola control measures: A mixed-methods study in a rural village in Sierra Leone. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiGiovanni, C.; Conley, J.; Chiu, D.; Zaborski, J. Factors influencing compliance with quarantine in Toronto during the 2003 SARS outbreak. Biosecur. Bioterror. 2004, 2, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Chan, L.Y.Y.; Chau, A.M.Y.; Kwok, K.P.S.; Kleinman, A. The experience of SARS-related stigma at Amoy Gardens. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 61, 2038–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetters, M.D.; Curry, L.A.; Creswell, J.W. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 48, 2134–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B. Basics of Grounded Theory Analysis; Sociology Press: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, D.; Tripathy, S.; Kar, S.K.; Sharma, N.; Verma, S.K.; Kaushal, V. Study of knowledge, attitude, anxiety & perceived mental healthcare need in Indian population during COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 51, 102083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Jacob, L.; Yakkundi, A.; McDermott, D.; Armstrong, N.C.; Barnett, Y.; López-Sánchez, G.F.; Martin, S.; Butler, L.; Tully, M.A. Correlates of symptoms of anxiety and depression and mental wellbeing associated with COVID-19: A cross-sectional study of UK-based respondents. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenham, C.; Smith, J.; Morgan, R. COVID-19: The gendered impacts of the outbreak. Lancet 2020, 395, 846–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, E.B. When disasters and age collide: Reviewing vulnerability of the elderly. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2001, 2, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Tian, W.; Liu, W.; Cao, Y.; Yan, J.; Shun, Z. Are the elderly more vulnerable to psychological impact of natural disaster? A population-based survey of adult survivors of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theme | In-Person Interviews | Survey Question a | Survey |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty | “I am lucky that I don’t have family members or friends that have been or are affected. That would change everything, if my mother or my daughters were in the hospital it would be different: more uncertainty, sadness, panic.” (IN11_M_43) | Uncertainty | In 77.5% of survey respondents, increased slightly (37.8%) or greatly (39.7%) |

| Symptoms on the depression spectrum | “The emotion of sadness, of apathy, of saying you don’t even feel like showering or anything... why should I get dressed or comb my hair, they’re things we have to do to keep up a routine, but as the days go it gradually stops.” (IN26_M_25) “This is hard and here at home there have been days when one of my children has been truly down, despairing, and the tears start to fall.” (IN19_M_33) | Feelings of depression, pessimism, or hopelessness | In 43.2% of survey respondents, increased slightly (33.4%) or greatly (9.8%) |

| Symptoms of anxiety, or reactions of anxiety, and feelings of loneliness | “Work gives me anxiety and being at home I can’t manage it and it’s with me all day. Once I get started it’s OK... when I finish working, I’m exhausted. My anxiety is worse, it was bad before, the anxiety, but now I feel very alone.” (IN02_F_35) “…, but now at home, with the anxiety... I can’t stop myself from snacking on a handful of crisps or chocolate.” (IN02_F_35) | Panic and anxiety attacks Feelings of loneliness | In 35.1% of survey respondents, panic increased slightly (27.1%) or greatly (8%) In 34.6% of survey respondents, feelings of loneliness increased slightly (24.9%) or greatly (9.7%) |

| Overwhelm/psychological distress | “I am starting to feel psychologically exhausted” (IN06_ M_41) “These are very difficult times. I am losing a lot of people; 4 family members and people close to me. You try to go out, take it in and they phone you and someone else... It’s very difficult. You cry and ask for psychological help.” (IN05_F_44) “Psychologically it’s going to affect us all, not being in contact with anyone, talking face to face, connecting, …” (IN21_M_24) | In 45.7% of survey respondents, increased slightly (36.2%) or greatly (9.5%) | |

| Worry about suffering from a serious disease | “...I haven’t left my house again, I had a thing in my lung and it scares me, I don’t go out, my husband comes, he comes with the shopping and we clean everything” (IN6_F_41). “…, I’m also scared of something happening to me” (IN35_F_60) | Worry about suffering from or contracting an illness (COVID-19 or other) | In 67.9% of survey respondents, worry about illness increased slightly (39.4%) or greatly (28.5%) |

| Irritation or anger | “At the beginning you fight the system a little, you are kind of against everything, and then you start to realize that it’s a very serious matter, that it’s not about you anymore, it’s about everyone else, that you have to stop and keep calm. And you also are seeing the news and you go from rebellion to alarm, fear, not knowing, the uncertainty, the nervousness...” (IN28_F_47) | Irritation or anger | In 47.4% of survey respondents, increased slightly (37.6%) or greatly (9.8%) |

| Fear of the death of loved ones | “Now it’s my mother who is in hospital and I’m afraid of how it’s going to progress. I am worried, I lost my father a week ago and I’m afraid of losing her, it’s distressing.” (IN25_M_41) “I was very afraid; my children lost their father in November and I don’t think they are ready to lose their mother.” (IN35_F_60) | Fear of losing loved ones | 75.5% of survey respondents increased slightly (40.4%) or greatly (35.1%) |

| Vitality-Energy | “In the mornings I don’t have energy and it’s hard to start working. Then during the day, since I’m distracted, I don’t think about things and at night when everyone goes to sleep, I feel like I get a little worse again, I think more about the situation we’re in, I’ve been a roller coaster. These days I’ve been telling my friends and family members that I love them a lot.” (IN01_M_22) | Feelings of vitality and energy | In 48.6% of survey respondents, these feelings decreased slightly (37.6%) or greatly (11%) |

| Disconnecting | “We are quite the homebodies, unconsciously because we are working and living in the same space, in the end, the work problems are there all the time, you don’t disconnect. Nervousness or anxiety is more due to work, that I can’t disconnect, more than due to being at home. Before I could discharge more energy and now I can’t.” (IN02_F_35) “When I was studying I could go out and disconnect, but now I can’t.” (IN26_M_35) | Ease of disconnecting from worries | In 34.3% of survey respondents, capacity to disconnect decreased slightly (24.5%) or greatly (9.8%) |

| Perception of control, being positive, relaxation | “When I found out I was working, and when I got home it hit me. I thought, ‘what do I do?’ The first days are hard due to your work, not continuing, worrying, and then you say, ‘I have to overcome this and try to be positive,’ for everyone around you, as well.” (IN28_F_47) | Feelings of confidence and optimism Feelings of peace, calm, relaxation | In 43.5% of survey respondents, feelings of optimism decreased slightly (35%) or greatly (8.5%). These feelings increased in 14.3% of survey respondents. In 43.9% of survey respondents, feelings of relaxation decreased slightly (33.1%) or greatly (10.8%). These feelings increased in 12.3% of survey respondents. |

| Problems and/or changes in sleep | “I have had to take sleeping pills” (IN14_F_55) | Problems sleeping | In 52.8% of survey respondents, this problem increased slightly (32.7%) or greatly (20.1%) |

| Suicidal thoughts Suicidal ideation | “A thousand things go through your mind, I think everything is over, nothing will be the same again; sometimes I think I don’t want to go on in this life, but then I think, no, I can’t talk that way, I have my daughters, my husband and my parents.” (IN05_F_44) | Thoughts of self-harm | In 4.5% of survey respondents, this type of ideation increased slightly (3.5%) or greatly (1%) |

| Unreality | “The first days it felt unreal, something is happening that has never happened and it just doesn’t seem normal” (IN18_F_30) | Feelings of unreality, that things are not real | In 42.7% of survey respondents, these feelings increased slightly (31.0%) or greatly (11.7%) |

| Concentration | “Because I’m not studying anything this month, I can’t concentrate, I’m sure my exam will be postponed until next year, I don’t know.” (IN6_F_41) “it’s hard to concentrate at home” (IN40_M_21) | Difficulty concentrating | In 41.2% of survey respondents, difficulty focusing increased slightly (29.1%) or greatly (12.1%) |

| Not thinking | “So it’s better to stop thinking about it and live day to day” (IN23_F_42) “...I try not to watch the news, not to think about it, to be at peace with the children.” (IN6_F_41) | Tendency to not want to think and to not talk about problems | In 31.9% of survey respondents, increased slightly (24%) or greatly (7.9%) |

| Guilt | “You go out and it feels like you’re committing a crime, that’s what makes me the most angry, even going to get bread or tobacco you feel bad. The TV chips away at your morale.” (IN4_M_62) | Feelings of guilt | In 13.8% of survey respondents, guilt feelings increased slightly (11.1%) or greatly (2.7%) |

| Prosocial behavior | “Next week we’re going to start helping at an organization.” (IN18_F_30) “The volunteer work I do is delivering food: we go to the location they have, there are shopping trolleys, we fill them with purchases, people come and get the food.” Also, sometimes I take shopping to my grandmother.” (IN40_M_21) | Willingness to help others (donations to NGOs, family members, etc.) | In 36.2% of survey respondents, prosocial behavior increased slightly (25.9%) or greatly (10.3%) |

| Somatic symptoms | “I’m getting a muscle spasm.” (IN38_F_29) “It’s hard for me to breathe, I sigh, I’m close to tears, I’m terrified to start the day…” (IN2_F_35) | Physical symptoms without a clear relationship to a medical condition | In 31.4% of survey respondents, somatic symptoms increased slightly (24.3%) or greatly (7.1%) |

| Mood swings | “I have days where I’m desperate to go out and times when I’m just down.” (IN25_M_41) | Mood swings | In 44.7% of survey respondents, increased slightly (34.2%) or greatly (10.5%). |

| Coping with problems | “Friends, family members, who are going to sort of solve the problems you might come to have.” (IN11_M_43) “Above all I have needed information, I’ve had to pay a lot of attention.” (IN9_F_50) | Ability to make decisions and solve problems | In 14.1% of survey respondents, capacity to solve problems decreased slightly or greatly. In 17.9% of survey respondents, it increased slightly or greatly. |

| Psychological Variables | Gender | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General psychological distress | Female | 1.7 | 3.6 | 42.7 | 39.7 | 12.1 |

| Male | 2.3 | 3.3 | 54.8 | 32.6 | 6.8 | |

| Difficulty concentrating | Female | 3.1 | 7.8 | 42.5 | 30.4 | 16.1 |

| Male | 1.8 | 7.8 | 54.7 | 27.8 | 7.8 | |

| Ease of disconnecting from worries | Female | 12.6 | 25.0 | 38.8 | 17.0 | 6.4 |

| Male | 6.9 | 24.0 | 47.9 | 17.0 | 4.2 | |

| Uncertainty | Female | 0.9 | 1.2 | 17.1 | 35.2 | 45.4 |

| Male | 1.2 | 1.7 | 22.6 | 40.5 | 33.8 | |

| Panic attacks | Female | 3.2 | 2.4 | 49.6 | 33.2 | 11.3 |

| Male | 3.4 | 3.2 | 67.9 | 20.6 | 4.6 | |

| Worry about suffering from or contracting a serious disease | Female | 1.9 | 1.2 | 28.1 | 38.2 | 30.2 |

| Male | 1.5 | 2.8 | 28.0 | 40.7 | 26.7 | |

| Tendency to not want to think and to not talk about problems | Female | 2.0 | 5.1 | 54.8 | 27.3 | 9.8 |

| Male | 2.0 | 6.5 | 64.7 | 20.6 | 6.0 | |

| Feelings of depression, pessimism, or hopelessness | Female | 2.8 | 3.6 | 43.2 | 37.8 | 11.9 |

| Male | 2.9 | 4.0 | 56.3 | 28.9 | 7.6 | |

| Feelings of guilt | Female | 3.5 | 3.6 | 74.8 | 12.9 | 4.1 |

| Male | 3.4 | 4.4 | 81.5 | 9.1 | 1.3 | |

| Thoughts of self-harm | Female | 9.8 | 2.2 | 79.2 | 3.4 | 1.3 |

| Male | 8.8 | 3.0 | 81.8 | 3.7 | 0.7 | |

| Fear of losing loved ones | Female | 0.5 | 0.8 | 18.6 | 38.9 | 40.5 |

| Male | 0.8 | 0.6 | 26.9 | 42.0 | 29.5 | |

| Feelings of loneliness | Female | 4.2 | 5.6 | 51.6 | 27.0 | 11.3 |

| Male | 3.2 | 5.1 | 60.9 | 22.7 | 8.0 | |

| Irritation or anger | Female | 2.1 | 3.7 | 41.6 | 40.3 | 12.1 |

| Male | 2.1 | 5.1 | 50.7 | 34.8 | 7.3 | |

| Mood swings | Female | 1.5 | 3.2 | 43.3 | 38.5 | 13.5 |

| Male | 1.4 | 4.9 | 56.6 | 29.8 | 7.3 | |

| Feelings of unreality, that things are not real | Female | 2.2 | 1.2 | 47.1 | 32.6 | 15.4 |

| Male | 2.2 | 2.4 | 58.0 | 29.3 | 7.9 | |

| Problems with sexual intercourse | Female | 5.2 | 6.3 | 65.7 | 10.9 | 7.9 |

| Male | 3.7 | 7.0 | 67.6 | 13.2 | 7.0 | |

| Problems sleeping | Female | 1.7 | 4.2 | 34.8 | 33.5 | 25.8 |

| Male | 1.5 | 5.0 | 47.3 | 31.9 | 14.2 | |

| Ability to make decisions and solve problems | Female | 2.9 | 12.8 | 65.2 | 13.3 | 5.7 |

| Male | 2.1 | 10.4 | 70.8 | 12.1 | 4.6 | |

| Feelings of confidence and optimism | Female | 10.5 | 37.1 | 38.1 | 11.3 | 2.8 |

| Male | 6.4 | 32.8 | 46.2 | 11.6 | 2.9 | |

| Feelings of peace, calm, relaxation | Female | 14.1 | 36.1 | 33.2 | 12.3 | 4.2 |

| Male | 7.5 | 30.1 | 45.7 | 11.5 | 5.2 | |

| Feelings of vitality and energy | Female | 14.2 | 40.0 | 32.8 | 10.6 | 2.4 |

| Male | 7.8 | 35.2 | 45.2 | 8.8 | 2.9 | |

| Willingness to help others | Female | 2.5 | 2.9 | 53.5 | 27.3 | 12.0 |

| Male | 3.5 | 3.7 | 59.3 | 24.2 | 8.4 | |

| Physical symptoms without a clear relationship to a medical condition | Female | 2.6 | 2.8 | 56.8 | 28.1 | 9.1 |

| Male | 1.9 | 3.1 | 69.4 | 20.4 | 5.0 |

| Psychological Variables | Age | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General psychological distress | 18–34 | 1.1 | 3.6 | 41.3 | 41.6 | 12.3 |

| 35–60 | 2.2 | 3.3 | 48.1 | 37.4 | 8.9 | |

| >60 | 2.8 | 3.9 | 59.0 | 26.5 | 7.5 | |

| Difficulty concentrating | 18–34 | 2.8 | 6.0 | 37.2 | 34.2 | 19.7 |

| 35–60 | 2.6 | 9.1 | 47.2 | 30.6 | 10.4 | |

| >60 | 1.7 | 6.7 | 65.8 | 19.1 | 6.6 | |

| Ability to disconnect from concerns | 18–34 | 13.4 | 27.9 | 36.4 | 16.4 | 5.8 |

| 35–60 | 9.2 | 24.7 | 42.5 | 17.8 | 5.7 | |

| >60 | 6.7 | 19.7 | 53.7 | 15.9 | 3.9 | |

| Uncertainty | 18–34 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 18.5 | 35.0 | 44.6 |

| 35–60 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 17.9 | 38.9 | 40.6 | |

| >60 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 26.3 | 38.5 | 31.4 | |

| Panic attacks | 18–34 | 1.8 | 3.6 | 52.4 | 30.5 | 11.4 |

| 35–60 | 3.5 | 2.3 | 59.2 | 27.5 | 7.2 | |

| >60 | 4.5 | 3.2 | 64.7 | 21.6 | 5.6 | |

| Worry about suffering from or contracting a serious disease | 18–34 | 2.6 | 3.3 | 32.4 | 39.6 | 22.1 |

| 35–60 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 28.3 | 37.6 | 30.3 | |

| >60 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 21.8 | 43.9 | 31.9 | |

| Tendency to not want to think and to not talk about problems | 18–34 | 1.5 | 6.5 | 53.9 | 26.8 | 10.7 |

| 35–60 | 1.7 | 5.3 | 61.0 | 24.5 | 7.0 | |

| >60 | 3.5 | 6.1 | 63.5 | 19.3 | 6.8 | |

| Feelings of depression, pessimism, or hopelessness | 18–34 | 1.6 | 3.5 | 44.6 | 36.7 | 13.1 |

| 35–60 | 2.9 | 3.8 | 49.5 | 33.9 | 9.4 | |

| >60 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 56.5 | 28.2 | 6.8 | |

| Feelings of guilt | 18–34 | 2.1 | 4.1 | 75.1 | 13.5 | 4.7 |

| 35–60 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 77.8 | 12.1 | 2.4 | |

| >60 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 82.8 | 5.4 | 1.0 | |

| Thoughts of self-harm | 18–34 | 7.4 | 1.6 | 82.5 | 3.2 | 2.0 |

| 35–60 | 10.1 | 2.8 | 79.2 | 3.9 | 0.8 | |

| >60 | 9.7 | 3.4 | 81.0 | 3.2 | 0.4 | |

| Fear of losing loved ones | 18–34 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 24.9 | 41.2 | 32.2 |

| 35–60 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 22.2 | 39.2 | 37.1 | |

| >60 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 21.3 | 42.6 | 34.1 | |

| Feelings of loneliness | 18–34 | 2.7 | 5.7 | 49.1 | 29.9 | 12.5 |

| 35–60 | 4.8 | 5.4 | 58.1 | 22.5 | 9.0 | |

| >60 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 60.1 | 24.7 | 7.9 | |

| Irritation or anger | 18–34 | 1.3 | 4.0 | 35.9 | 44.4 | 14.3 |

| 35–60 | 2.4 | 4.3 | 46.2 | 38.7 | 8.3 | |

| >60 | 2.5 | 4.8 | 58.3 | 26.2 | 7.7 | |

| Mood swings | 18–34 | 1.0 | 2.7 | 40.1 | 39.8 | 16.3 |

| 35–60 | 1.2 | 4.5 | 49.0 | 36.0 | 9.3 | |

| >60 | 2.5 | 4.5 | 64.0 | 22.8 | 6.0 | |

| Feelings of unreality, that things are not real | 18–34 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 52.1 | 29.7 | 13.2 |

| 35–60 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 51.2 | 33.5 | 10.7 | |

| >60 | 2.1 | 2.9 | 56.0 | 26.2 | 12.4 | |

| Problems with sexual intercourse | 18–34 | 5.1 | 6.5 | 60.4 | 14.9 | 10.1 |

| 35–60 | 4.6 | 6.9 | 66.4 | 12.6 | 7.6 | |

| >60 | 3.3 | 6.3 | 75.0 | 6.9 | 3.9 | |

| Problems sleeping | 18–34 | 1.6 | 4.8 | 32.6 | 31.1 | 29.9 |

| 35–60 | 1.6 | 4.5 | 40.7 | 34.1 | 19.0 | |

| >60 | 1.8 | 4.4 | 52.0 | 31.3 | 10.5 | |

| Ability to make decisions and solve problems | 18–34 | 3.4 | 16.6 | 59.3 | 13.4 | 7.2 |

| 35–60 | 2.3 | 10.4 | 68.6 | 13.9 | 4.7 | |

| >60 | 2.3 | 8.3 | 77.0 | 8.7 | 3.9 | |

| Feelings of confidence and optimism | 18–34 | 9.0 | 34.3 | 40.7 | 13.2 | 2.7 |

| 35–60 | 8.3 | 36.3 | 41.2 | 11.4 | 2.7 | |

| >60 | 8.3 | 32.7 | 45.9 | 9.5 | 3.4 | |

| Feelings of peace, calm, relaxation | 18–34 | 13.0 | 35.2 | 33.4 | 13.4 | 4.9 |

| 35–60 | 11.4 | 33.7 | 39.1 | 11.1 | 4.6 | |

| >60 | 6.7 | 29.3 | 47.5 | 12.0 | 4.6 | |

| Feelings of vitality and energy | 18–34 | 15.4 | 38.4 | 31.3 | 12.3 | 2.4 |

| 35–60 | 10.4 | 40.5 | 37.7 | 8.9 | 2.5 | |

| >60 | 7.2 | 29.7 | 51.4 | 8.4 | 3.2 | |

| Willingness to help others | 18–34 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 53.6 | 28.5 | 10.7 |

| 35–60 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 58.8 | 23.4 | 9.2 | |

| >60 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 53.8 | 28.3 | 12.4 | |

| Physical symptoms without a clear relationship to a medical condition | 18–34 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 58.7 | 28.4 | 8.4 |

| 35–60 | 2.2 | 3.5 | 61.8 | 25.0 | 7.0 | |

| >60 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 71.3 | 17.4 | 5.7 |

| Psychological Variables | SEL | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General psychological distress | High | 1.8 | 3.8 | 49.5 | 35.6 | 9.3 |

| Medium | 2.2 | 3.3 | 48.1 | 36.7 | 9.4 | |

| Low | 1.9 | 3.4 | 47.9 | 36.4 | 10.0 | |

| Difficulty concentrating | High | 2.6 | 6.7 | 46.4 | 32.3 | 12.0 |

| Medium | 2.3 | 8.2 | 50.6 | 27.0 | 11.9 | |

| Low | 2.5 | 9.0 | 48.4 | 27.5 | 12.6 | |

| Ability to disconnect from concerns | High | 11.3 | 25.0 | 40.7 | 18.5 | 4.4 |

| Medium | 9.3 | 25.4 | 42.9 | 16.9 | 5.5 | |

| Low | 8.1 | 21.8 | 48.5 | 14.6 | 6.6 | |

| Uncertainty | High | 1.1 | 1.2 | 18.9 | 37.0 | 41.7 |

| Medium | 0.6 | 1.6 | 19.6 | 40.0 | 38.1 | |

| Low | 1.6 | 1.7 | 22.0 | 35.0 | 39.1 | |

| Panic attacks | High | 3.2 | 2.9 | 61.5 | 23.9 | 8.3 |

| Medium | 3.2 | 2.6 | 57.1 | 29.9 | 7.0 | |

| Low | 3.4 | 3.1 | 56.0 | 27.6 | 9.3 | |

| Worry about suffering from or contracting a serious disease | High | 1.5 | 2.5 | 29.1 | 39.4 | 27.4 |

| Medium | 1.8 | 1.5 | 26.8 | 39.6 | 29.9 | |

| Low | 2.1 | 2.0 | 28.2 | 39.3 | 27.7 | |

| Tendency to not want to think and to not talk about problems | High | 2.3 | 6.3 | 58.6 | 24.5 | 7.8 |

| Medium | 1.6 | 5.6 | 60.8 | 23.8 | 7.4 | |

| Low | 2.3 | 5.3 | 59.5 | 23.4 | 9.2 | |

| Feelings of depression, pessimism, or hopelessness | High | 2.6 | 2.9 | 52.7 | 32.1 | 9.4 |

| Medium | 3.3 | 4.1 | 47.7 | 35.8 | 8.8 | |

| Low | 2.6 | 4.8 | 47.8 | 31.6 | 12.4 | |

| Feelings of guilt | High | 2.8 | 5.2 | 76.8 | 12.2 | 2.8 |

| Medium | 3.9 | 3.5 | 79.3 | 9.9 | 2.6 | |

| Low | 3.8 | 2.7 | 78.5 | 11.3 | 2.8 | |

| Thoughts of self-harm | High | 8.8 | 2.8 | 83.1 | 2.4 | 0.9 |

| Medium | 9.2 | 2.3 | 79.9 | 4.4 | 0.9 | |

| Low | 10.4 | 2.8 | 76.6 | 4.1 | 1.6 | |

| Fear of losing loved ones | High | 0.3 | 0.3 | 23.5 | 42.4 | 33.3 |

| Medium | 0.9 | 0.8 | 21.1 | 40.2 | 36.6 | |

| Low | 0.7 | 1.2 | 24.2 | 37.2 | 36.0 | |

| Feelings of loneliness | High | 3.9 | 6.6 | 57.5 | 23.6 | 8.4 |

| Medium | 3.8 | 4.7 | 56.3 | 26.1 | 8.7 | |

| Low | 3.1 | 4.3 | 53.4 | 25.0 | 13.9 | |

| Irritation or anger | High | 2.2 | 3.8 | 42.9 | 40.3 | 10.6 |

| Medium | 1.9 | 5.0 | 48.0 | 36.7 | 8.4 | |

| Low | 2.4 | 4.1 | 48.2 | 34.3 | 10.8 | |

| Mood swings | High | 1.5 | 2.7 | 49.1 | 35.9 | 10.8 |

| Medium | 1.2 | 5.0 | 49.7 | 34.2 | 9.9 | |

| Low | 1.6 | 4.7 | 51.3 | 31.3 | 10.9 | |

| Feelings of unreality, that things are not real | High | 2.0 | 1.5 | 50.8 | 32.0 | 12.6 |

| Medium | 2.3 | 1.9 | 53.5 | 30.4 | 11.1 | |

| Low | 2.4 | 2.1 | 53.5 | 30.1 | 11.1 | |

| Problems with sexual intercourse | High | 4.7 | 7.2 | 64.7 | 13.7 | 7.3 |

| Medium | 3.7 | 7.1 | 68.1 | 11.4 | 7.6 | |

| Low | 5.4 | 5.0 | 67.6 | 9.8 | 7.5 | |

| Problems sleeping | High | 1.6 | 4.5 | 39.9 | 33.9 | 20.1 |

| Medium | 1.7 | 5.0 | 40.7 | 33.2 | 19.4 | |

| Low | 1.5 | 4.0 | 43.3 | 29.7 | 21.5 | |

| Ability to make decisions and solve problems | High | 2.6 | 12.3 | 66.3 | 12.3 | 6.4 |

| Medium | 2.1 | 11.2 | 69.6 | 12.5 | 4.5 | |

| Low | 3.2 | 11.1 | 67.8 | 13.6 | 4.1 | |

| Feelings of confidence and optimism | High | 8.9 | 35.4 | 40.4 | 12.7 | 2.4 |

| Medium | 7.1 | 36.5 | 43.9 | 10.0 | 2.6 | |

| Low | 10.3 | 31.7 | 41.7 | 11.9 | 4.2 | |

| Feelings of peace, calm, relaxation | High | 10.6 | 33.0 | 39.2 | 11.9 | 5.3 |

| Medium | 11.2 | 33.7 | 39.3 | 11.9 | 3.8 | |

| Low | 10.6 | 32.5 | 39.6 | 12.0 | 5.2 | |

| Feelings of vitality and energy | High | 12.2 | 35.5 | 38.7 | 11.1 | 2.4 |

| Medium | 10.3 | 39.5 | 39.6 | 7.6 | 3.0 | |

| Low | 10.5 | 38.2 | 37.9 | 10.8 | 2.3 | |

| Willingness to help others | High | 2.3 | 3.1 | 53.9 | 28.4 | 11.6 |

| Medium | 2.6 | 3.3 | 57.5 | 25.5 | 9.7 | |

| Low | 4.7 | 3.6 | 58.7 | 21.5 | 8.9 | |

| Physical symptoms without a clear relationship to a medical condition | High | 1.7 | 4.0 | 64.0 | 23.4 | 6.7 |

| Medium | 2.8 | 2.2 | 62.5 | 25.0 | 7.0 | |

| Low | 2.3 | 2.6 | 62.1 | 24.6 | 8.0 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hidalgo, M.D.; Balluerka, N.; Gorostiaga, A.; Espada, J.P.; Santed, M.Á.; Padilla, J.L.; Gómez-Benito, J. The Psychological Consequences of COVID-19 and Lockdown in the Spanish Population: An Exploratory Sequential Design. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8578. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228578

Hidalgo MD, Balluerka N, Gorostiaga A, Espada JP, Santed MÁ, Padilla JL, Gómez-Benito J. The Psychological Consequences of COVID-19 and Lockdown in the Spanish Population: An Exploratory Sequential Design. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(22):8578. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228578

Chicago/Turabian StyleHidalgo, María Dolores, Nekane Balluerka, Arantxa Gorostiaga, José Pedro Espada, Miguel Ángel Santed, José Luis Padilla, and Juana Gómez-Benito. 2020. "The Psychological Consequences of COVID-19 and Lockdown in the Spanish Population: An Exploratory Sequential Design" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 22: 8578. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228578

APA StyleHidalgo, M. D., Balluerka, N., Gorostiaga, A., Espada, J. P., Santed, M. Á., Padilla, J. L., & Gómez-Benito, J. (2020). The Psychological Consequences of COVID-19 and Lockdown in the Spanish Population: An Exploratory Sequential Design. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8578. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228578