Abstract

Background: Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) is a psychological intervention with established efficacy in the prevention and treatment of depressive disorders. Previous systematic reviews have not evaluated the effectiveness of IPT on symptoms of stress, anxiety, depression, quality of life, relationship satisfaction/quality, social supports, and an improved psychological sense of wellbeing. There is limited information regarding moderating and mediating factors that impact the effectiveness of IPT such as the timing of the intervention or the mode of delivery of IPT intervention. The overall objective of this systematic review was to evaluate the effectiveness of IPT interventions to treat perinatal (from pregnancy up to 12 months postpartum) psychological distress. Methods: MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), PsycINFO (Ovid), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (OVID), CINAHL with Full Text (Ebsco), Social Work Abstracts (Ebsco), SocINDEX with Full Text (Ebsco), Academic Search Complete (Ebsco), Family & Society Studies Worldwide (Ebsco), Family Studies Abstracts (Ebsco), and Scopus databases were searched from inception until 31 January 2019. Two researchers independently screened articles for eligibility. Of the 685 screened articles, 43 met the inclusion criteria. The search was re-run on 11 May 2020. An additional 204 articles were screened and two met the inclusion criteria, resulting in a total of 45 studies included in this review. There were 25 Randomized Controlled Trials, 10 Quasi-experimental studies, eight Open Trials, and two Single Case Studies. All included studies were critically appraised for quality. Results: In most studies (n = 24, 53%), the IPT intervention was delivered individually; in 17 (38%) studies IPT was delivered in a group setting and two (4%) studies delivered the intervention as a combination of group and individual IPT. Most interventions were initiated during pregnancy (n = 27, 60%), with the remaining 18 (40%) studies initiating interventions during the postpartum period. Limitations: This review included only English-language articles and peer-reviewed literature. It excluded government reports, dissertations, conference papers, and reviews. This limited the access to grassroots or community-based recruitment and retention strategies that may have been used to target smaller or marginalized groups of perinatal women. Conclusions: IPT is an effective intervention for the prevention and treatment of psychological distress in women during their pregnancy and postpartum period. As a treatment intervention, IPT is effective in significantly reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety as well as improving social support, relationship quality/satisfaction, and adjustment. Systematic Review Registration: PROSPERO CRD42019114292.

Keywords:

systematic review; interpersonal psychotherapy; antenatal; perinatal; postpartum; women; distress 1. Background

The perinatal period is a time of increased social, emotional, biological, and psychological adjustments for women [,]. Pregnancy and the first 12 months postpartum is a developmental life stage for women which requires adjustments to changes in their physical appearance and expectations for new responsibilities [,]. As such, perinatal women are at increased susceptibility to psychological stress and alterations in perceived wellbeing [,]. Psychological distress, including stress, anxiety, and depression, resulting from pregnancy and the postpartum period is common, occurring in 15% to 25% of perinatal women [,]. The impact of perinatal stress, anxiety, and depression is far reaching and associated with impaired mother-fetal/infant relationships, obstetrical complications, and child cognitive-developmental problems [,]. Left untreated, approximately 40% of these women will have symptoms that persist until their children enter the school system [,]. Unfortunately, perinatal stress, anxiety, and depression often go undetected and untreated [,,]. Effective treatment of perinatal mental health concerns is imperative.

Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) is considered a highly effective treatment for anxiety and depression [,,]. Studies examining the efficacy of IPT during the perinatal period appear promising [,,]. Stuart and O’Hara (1995) [] reported that IPT is well-suited to the needs of perinatal women as IPT focuses on four areas that are significant factors in the prediction and maintenance of perinatal mental health concerns. These factors include role transitions, interpersonal disputes, grief and loss, and interpersonal deficits []. First, consistent with the focus of IPT, role transitions associated with becoming parents correlate with perinatal mental health symptoms and resulting interpersonal relationship disputes [,,]. Secondly, interpersonal disputes are one of the most significant stressors for couples during the perinatal period. Next, grief and loss during the perinatal period are also a focus of IPT []. Finally, interpersonal deficits, in particular low social support and marital discord, are strongly associated with perinatal anxiety and depression [,].

IPT is an intervention aimed at alleviating psychological symptoms, coping with problems due to loss, change, and relationship conflict, thereby improving interpersonal functioning [,]. It is based on the concept that when faced with adversity, factors such as attachment styles, communication patterns, and the quality of social support networks contribute considerably to an individual’s range of symptoms of psychological distress []. Conceptualizations of social supports come from work on attachment theory, trust, and coping in times of adversity []. These social supports play an important role in how individuals navigate the coping process and manage stress [,]. Social supports vary in type and can include emotional support, practical help, social companionship, and motivational support []. Emotional support offers reassurance about individuals’ self-worth, unconditional positive regard, and the opportunity for confiding [,]. Practical help, also known as instrumental or tangible support, provides direct assistance [,]. Social companionship is important as it facilitates individuals engaging in leisure activities []. Motivational support is defined as help that supports an individual’s plan or goals []. IPT endeavours to improve attachment security, interpersonal change, and psychological distress [,] as a mechanism for improving individual coping and resilience.

In addition to the four salient areas of focus, IPT is consistent with many women’s desire to self-manage their mental health concerns [,]. While the literature suggests that psychological therapy is effective, perinatal women report significant barriers to seeking psychological support. These barriers include stigma (self and by their healthcare professional), uncertainty about whether their symptoms are normal or abnormal, inability to articulate their distress, wanting the opportunity to self-manage first, not wanting to take psychotropic medications, lack of time, financial expenditure, location and proximity of services, transportation issues, and challenges associated with childcare [,,]. Therefore, instead of using formal treatments, women are more inclined to seek the informal support of friends and family, printed material, or computer/web-based intervention programs [,,].

In a recent systematic review (2018) looking at the efficacy of IPT in perinatal women, 28 studies endorsed the effectiveness of IPT in the prevention and/or treatment of perinatal distress []. However, the review lacked adherence to systematic literature review best practices as the search was limited to two databases, screening was completed by only one reviewer, and the search strategy included limited keywords, did not include variations of terms as hyphenated terms (e.g., peri-natal), and did not include subject headings []. As such, clinicians, researchers, and decisionmakers would benefit from a systematic, comprehensive, and transparent approach to examining the use of IPT in perinatal women.

The goal of the current systematic review was to synthesize the current literature, evaluating the effectiveness, feasibility, and acceptability of IPT interventions to treat perinatal psychological distress. The question guiding this systematic review was: What is the effectiveness of IPT for women during the perinatal period on the reduction of stress, anxiety, and depression and improvement in quality of life, relationship satisfaction/quality, social support, and psychological wellbeing?

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

The protocol for this systematic review was developed based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses Protocols (PRISMA-P) [] and has been registered with PROSPERO CRD42019114292. The systematic literature protocol paper has also been published (K. S. Bright et al., 2019) [].

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The studies selected for inclusion in this systematic review met the following eligibility criteria, which are described according to participants, study design (including publication, language, and year), intervention, and outcomes.

2.3. Participants

Perinatal women from conception to 12 months postpartum who participated in an IPT intervention were included. For this systematic review, we excluded women who were not pregnant or postpartum.

2.4. Study Design

The review considered studies evaluating the feasibility, acceptability, effectiveness, and/or efficacy of IPT in perinatal women. Experimental studies such as randomized controlled/clinical trials (RCTs), quasi-experimental studies, as well as single group pre-post studies were included in the review. Observational studies, including cohort and case control studies, were included. We included qualitative studies that explored the acceptability of IPT interventions. We excluded conference papers, dissertations, reviews, and non-English publications.

2.5. Interventions

We defined IPT intervention as interpersonal therapy, or any intervention, counseling, psychotherapy, therapy, or program where there was a component of IPT offered. IPT included those interventions targeted towards women during the perinatal period.

2.6. Comparator

We included studies with all types of comparator groups, such as pre-post interventions, non-exposed control group, or a group exposed to a different intervention.

2.7. Information Sources and Search Strategy

MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), PsycINFO (Ovid), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (OVID), CINAHL with Full Text (Ebsco), Social Work Abstracts (Ebsco), SocINDEX with Full Text (Ebsco), Academic Search Complete (Ebsco), Family & Society Studies Worldwide (Ebsco), Family Studies Abstracts (Ebsco), and Scopus databases were searched from database inception to 31 January 2019 and rerun on 11 May 2020. (See Supplementary Materials for the Medline search strategy).

2.8. Screening of Studies

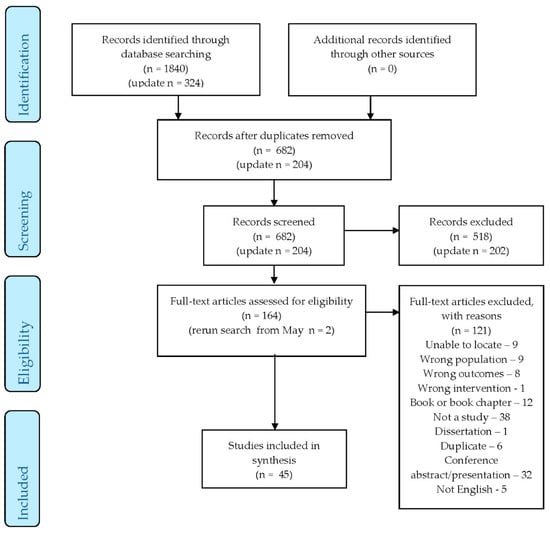

Prior to screening, the two reviewers (KSB and EMC) completed a calibration exercise where 10% of studies were reviewed independently and then together assessed for inter-rater agreement. In the calibration exercise, there was 93% agreement. Following the calibration exercise, the two reviewers independently screened the studies for eligibility in two steps. The first step consisted of reviewing all studies’ titles/abstracts to identify studies that met the eligibility criteria. The second step consisted of reviewing the provisionally included studies’ full text to ensure that they met all the inclusion criteria. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers. There were 45 studies that met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1. PRISMA Diagram).

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) Diagram.

2.9. Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

Studies were included regardless of methodological quality. The Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool was used for quality assessment. Two reviewers (KSB and EMC) independently assessed all studies for quality and disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

Characteristics of the 45 studies included in this systematic review are presented in Table 1. There were 25 (56%) RCTs, 10 (22%) quasi-experimental studies, eight (18%) open trials, and two (4%) single cases. Of these studies, 33 (73%) provided IPT as a treatment and 12 (27%) provided it for prevention. Most studies (n = 28, 62.2%) were conducted in the USA, with 11.1% (five) in China, 6.7% (three) in Australia, 4.4% (two) in Canada, 4.4% (two) in Hong Kong, 2.2% (one) in Iran, 2.2% (one) in Singapore, 2.2% (one) in Austria, 2.2% (one) in Hungary, and 2.2% (one) in Israel. Among the RCTs and quasi-experimental studies, 15 (48.6%) used comparisons of treatment as usual (TAU), 16 (37.1%) were active treatment, three (8.6%) were waitlist control (WLC), one (2.9%) was WLC and TAU, and one (2.9%) was WLC and active treatment. Of the active treatment comparison type studies, six studies used education-based programs, four studies used psychological programs/sessions, two studies used antidepressant medications, and one used mindfulness-based therapy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies.

Characteristics of the interventions are presented in Table 2. In most studies (n = 24, 53%), the IPT intervention was delivered individually; in 17 (38%) studies IPT was delivered in a group setting, two (4%) studies delivered the intervention as a combination of group and individual IPT, and two (4%) studies included partners in the delivery of the intervention. Most studies (n = 29, 64.4%) delivered the IPT face-to-face, while two (4.4%) studies delivered IPT over the phone and 14 (31.1%) studies combined face-to-face and telephone calls.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Interventions.

Most interventions were initiated during pregnancy (n = 27, 60%), with the remaining 18 (40%) studies initiated during the postpartum period. IPT was administered individually in 24 (53%) studies and in groups in 17 (38%) studies. Women’s partners were included in the intervention in two (4%) studies. Most studies (n = 30, 66.7%) provided IPT in a community setting (e.g., women’s recreation facility), 12 (26.7%) studies provided IPT in the clinical setting (e.g., prenatal clinic), and three (6.7%) studies provided IPT in a mixed clinical and community setting. The number of IPT sessions ranged from two to 16 sessions, with an average of eight sessions. Most studies (n = 35, 78%) reported provided IPT according to a study or intervention protocol.

Characteristics of the method of assessment for outcomes are presented in Table 3. In most studies (n = 28, 62.2%), depressive symptoms were assessed using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), while 16 (35.6%) studies used the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), 16 (35.6%) used the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), three (6.7%) studies used the CESD, and three (6.7%) studies used the SCL-20. Symptoms of anxiety were assessed in 18 (40%) studies, most commonly using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory and Beck Anxiety Inventory. Stress levels were assessed in 10 (22%) of the studies. Maternal-infant attachment was assessed in 16 (36%) of the studies. Eleven (24%) of the studies assessed social support. Relationship satisfaction/quality was assessed in 17 (38%) of the studies.

Table 3.

Method of Assessment for Outcomes in Included Analyses.

Characteristics of study methodological quality are presented in Table 4. Methodological quality was assessed using the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool []. The study scores ranged from 1 (strong) to 3 (weak), with an average of 2 (moderate). There were 18 studies (40%) categorized as strong overall, 14 (31%) studies were moderate overall, and 13 (29%) studies were weak overall. Study design was assessed as strong in 26 (57.8%) studies, intervention integrity was determined to be strong in 35 (78%) studies, and data analysis was assessed as strong in 20 (44%) studies.

Table 4.

Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool.

Among the studies that reported sample demographic characteristics, maternal age ranged from 18 to 38 years old with a mean age of 30 years. The average gestational age for pregnant women ranged from six to 40 weeks, with an average of 23.7 weeks. The weeks postpartum of participants ranged from 0.5 to 96 weeks postpartum, with an average of 24.4 weeks.

3.2. Prevention Studies

Among the 13 prevention studies, 12 (92%) were delivered during pregnancy and one (8%) was delivered in the postpartum period.

3.3. Treatment Studies

Among the 33 treatment studies, 16 (48.5%) were delivered during the prenatal period and 17 (51.5%) studies were delivered in the postpartum period.

3.4. Change in Depressive Symptoms Between Treatment and Comparison Groups

Twelve prevention studies aimed to reduce the risk of depression in participants receiving IPT. Five studies [,,,,] reported a significant reduction of depressive symptoms levels over time. These improvements were small to moderate in magnitude. No studies had large effect sizes. Reductions in depressive symptoms were also significantly larger in studies where IPT was delivered in a group format compared to individual IPT.

Thirty-two (71%) treatment studies assessed change in depressive symptoms among participants receiving IPT. Twenty-six studies reported a significant improvement in depressive symptoms over time. The improvements were determined to be in the moderate to large range. Reductions in depressive symptoms were more common in studies where the interventions were initiated in the postpartum period than in studies where interventions were initiated during pregnancy.

3.5. Change in Anxiety Symptoms Between Treatment and Comparison Groups

Seven prevention studies aiming to reduce the risk of symptom levels of anxiety addressed the change in symptoms of anxiety among participants receiving IPT. One study (Bowen et al., 2014) reported a significant reduction in the risk level of anxiety symptoms. The effect size of the intervention on symptoms of anxiety was not reported in this study.

Eleven treatment studies assessed the change in symptoms of anxiety among participants receiving IPT. Six studies [,,,,,] reported significant reductions in symptoms of anxiety. There was an overall reduction in symptoms of anxiety among participants receiving IPT, with an effect size in the moderate range. More studies of individual delivery showed a reduction in anxiety than group delivery. Reductions in anxiety were also noted more frequently in studies where IPT was delivered in a medical/clinical setting compared to a community setting.

3.6. Change in Stress Symptoms Between Treatment and Comparison Groups

Three prevention studies aimed at reducing the risk of stress levels assessed change in symptoms of stress among participants receiving IPT. Two studies (Bowen et al., 2014; Leung & Lam, 2012) reported a significant reduction in the risk of symptom levels of stress. One study did not report an effect size of the intervention and the other reported a very small effect size (Leung & Lam, 2012).

Seven treatment studies assessed for change in symptoms of stress among women receiving IPT. Two of these studies (Field et al., 2009; Field et al., 2013) reported a significant reduction in symptoms of stress for participants receiving IPT. The effect sizes of the intervention were not reported.

3.7. Change in Relationship Quality Between Treatment and Comparison Groups

Three prevention studies aiming to reduce the risk of relationship distress assessed relationship quality/satisfaction among participants receiving IPT. There were no studies that reported a significant improvement in relationship quality/satisfaction.

Twelve treatment studies assessed relationship quality/satisfaction among women receiving IPT. Four studies (Chung, 2015; Field et al., 2013; Hajiheidari et al., 2013; Mulcahy et al., 2010) reported significant improvements in relationship quality, with an effect size in the small range. Studies with married/cohabitating participants were more likely to have greater improvements in their relationship quality than those women without partners.

3.8. Change in Social Support Between Treatment and Comparison Groups

Four prevention studies aiming to reduce the risk of distress related to poor support assessed social support among participants receiving IPT. Three of these studies (L. L. Gao et al., 2012; L. L. Gao et al., 2012; L. L. Gao et al., 2015) reported significant improvements in social support. The effect size was in the small range.

Seven treatment studies assessed the change in social support among participants receiving IPT. Three studies (Lenze & Potts, 2017; Lenze et al., 2015; Mulcahy et al., 2010) reported significant improvements in social support. The effect size was in the medium to large range. Studies with participants who had higher levels of education were more likely to experience significant improvements in social support.

3.9. Change in Attachment Levels Between Treatment and Comparison Groups

There were no prevention studies that assessed attachment. There were eight treatment studies that assessed attachment among participants receiving IPT. Three of these studies (Mulcahy et al., 2010; Posmontier et al., 2019; Spinelli, Endicott, Leon, et al., 2013) reported significant improvements in attachment. While these improvements were reported to be statistically significant, the effect size of the IPT intervention was not reported.

3.10. Change in the Level of Adjustment Between Treatment and Comparison Groups

There was one prevention study aiming to reduce the risk of poor adjustment that assessed for adjustment among participants receiving IPT. This one study (Crockett et al., 2008) reported that the level of adjustment was statistically significant only between 2–3 weeks and 3 months postpartum. No effect size was reported.

There were 12 treatment studies that assessed for level of adjustment among participants receiving IPT. There were no studies that reported any significant improvements in level of adjustment.

4. Discussion

This review of the literature provides evidence that IPT is an effective intervention for the prevention and treatment of psychological distress in women during their pregnancy and postpartum period. As a preventive intervention, IPT is superior to comparison conditions, including active interventions, treatment-as-usual, and no intervention, for reducing the risk of depression. As a treatment intervention, IPT is effective in significantly reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety as well as improving social support, relationship quality/satisfaction, and adjustment. IPT is superior to comparison conditions including active interventions, treatment-as-usual, and no intervention for reducing depressive symptoms as well as improving social support and relationship quality.

There is evidence supporting the use of IPT to prevent depression in perinatal women. These findings suggest that IPT is effective as both a prevention intervention and for those women at high risk due to the presence of risk factors including a previous diagnosis of depression (Zlotnick et al., 2006) or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Grote et al., 2015; Grote et al., 2017; Zlotnick et al., 2011). There was one preventive study that reported outcomes for symptoms of anxiety (Bowen et al., 2014). This study found that IPT was effective in reducing anxiety symptoms and worry over time in pregnant women compared to active interventions, treatment-as-usual, and no interventions. Given the far reaching impact of prenatal anxiety on women and their children (Brunton, et al, 2015 []; Mughal et al., 2019 []; Brunton, Dryer, Field, 2017 []; K. Bright & Becker, 2019 []), future research exploring preventive interventions in prenatal women would benefit from including assessment of anxiety in addition to depressive symptoms. There is a need for investigating the diagnostic outcomes of anxiety and anxiety-related disorders, including the prevalence of perfectionism and obsessive-compulsive disorder, as preliminary work in this area suggests that there is increased risk for these disorders during the perinatal period (Kane, Winton, Eliot, & McEvoy, 2017 []; Lowndes, Egan, & McEvoy, 2019 []; Standeven, Nestadt, & Samuels, 2020 [], Buchholz, Hellberg, & Egan, Abramowitz, 2020 [];).

In this review, group prevention interventions resulted in greater reduction in risk of symptom levels of depressive than individually administered interventions. Groups have a valuable set of therapeutic characteristics where women are provided with a supportive network of peers with shared feelings, thoughts, and problems (Marmarosh, Holtz, & Schottenbauer, 2005) []. Women gain insight into the universality of their problems, which helps to normalize their experiences (Reay et al., 2006). Group therapy allows women to increase their coping strategies, knowledge, and skill through vicarious learning. Helping others solve their problems can increase their sense of competence. It may also be that the social skills and competencies gained through group-based IPT prevent the onset of depressive symptoms by specifically moderating relationship challenges.

While RCTs of IPT for mental health disorders show a moderate to large effect on depression compared with control groups, IPT has not been found to be more effective than other psychotherapies such as CBT for depression (Cuijpers, Donker, Weissman, Ravitz, & Cristea, 2016 []; Jakobsen, Hansen, Simonsen, Simonsen, & Gluud, 2012 []). Research does suggest that pharmacotherapy may be mildly more effective than psychotherapies (Cuijpers et al., 2016 []; Cuijpers, van Straten, Andersson, & van Oppen, 2008 []). When pharmacotherapy is combined with psychotherapy, it is not more effective than pharmacotherapy alone, but is more effective than IPT alone (Cuijpers et al., 2016 []; Nillni, Mehralizade, Mayer, & Milanovic, 2018 []).

There was a trend that more studies of individually administered IPT showed a reduction of anxiety symptoms than group offered IPT. Individual therapy has the advantage of participants receiving greater attention to their individual issues, closer monitoring of symptoms, and more tailored adaptation of the intervention to issues that are particularly relevant to the individual (O’Shea, Spence, & Donovan, 2015) []. Previous literature reviews and meta-analyses have obtained contradictory findings (Cuijpers et al., 2008; Goodman & Santangelo, 2011; L.E. Sockol, Epperson, & Barber, 2011; L. E. Sockol, Epperson, & Barber, 2013) [,,,]. Future preventive and treatment research would benefit from including assessment of acceptability of group and individual therapy. Investigation of potential predictors of treatment efficacy should include a history of depressive disorders and anxiety-related disorders as well as their comorbidity to determine if these characteristics are associated with delivery method and differential efficacy.

In six RCTs examining the effect of IPT on anxiety, compared to other psychotherapies, this resulted in a small nonsignificant difference in favour of the alternative therapies such as CBT over IPT (Cuijpers et al., 2016; Nillni et al., 2018) [,]. There is one study investigating the effect of paroxetine and CBT compared to CBT alone and it was found that there was no significant difference between groups (Misri, Reebye, Corral, & Mills, 2004) []. Given the paucity of research in this area, this is concerning given that anxiety symptoms and comorbid symptoms are prevalent in perinatal women, therefore it is important that there is further research on effective treatments.

4.1. Strengths

There are numerous strengths of this systematic review, which include explicit methods description and comprehensive database searches to methodologically search for articles exploring the use of IPT/IPT-based interventions in the perinatal population. This transparent and systematic approach to reviewing the literature included the use of a librarian for the search and two reviewers with content expertise for the assessment of inclusion and data extraction attempted to reduce reviewer bias. This rigorous process facilitates a reproducible and objective criteria to select relevant studies and adequately assess their quality.

4.2. Limitations

A major limitation of the studies evaluating IPT, whether for prevention or treatment, is that few studies addressed outcomes such as social support, relationships, and adjustment the same way. Improving these interpersonal areas are among the goals of IPT. As such, there needs to be consistency in how these elements are operationalized in a perinatal population. Implications for future IPT intervention studies involve assessing perinatal women’s change in interpersonal functioning and involving women’s partners in treatment.

Findings from this review of IPT in perinatal women are limited to IPT being delivered face-to-face or via telephone. Literature examining online IPT in non-perinatal populations suggests that despite high dropout rates, internet-delivered self-guided IPT is effective in reducing depressive symptoms (Donker et al., 2013). Future research requires well-designed RCTs that compare internet-delivered IPT to active, treatment-as-usual, and no treatment. Additionally, internet-based IPT trials will need to assess differences in prevention versus treatment, prenatal versus postpartum women, and group versus individual treatment.

This review is limited by the lack of detailed descriptions of recruitment and retention strategies of the individual studies. Further limitations include the inclusion/exclusion criteria of reviewing only English-language articles, which may reduce generalizability to non-English speaking populations. Similarly, this review included only peer-reviewed literature and excluded government reports, dissertations, conference papers, and reviews. This limited the access to grassroots or community-based recruitment and retention strategies that may have been used to target smaller or marginalized groups of perinatal women.

4.3. Research Implications

Further studies would benefit from refinement of the perinatal IPT treatment. In future studies, the IPT intervention will need to include a comprehensive IPT manual to promote adherence/competence measures. Perinatal IPT research will also benefit from development of far-reaching training programs for those delivering IPT in research, community, and clinical settings. Improving the structure of IPT and training of clinicians who can deliver evidence-based IPT has the potential to improve outcomes for perinatal women.

Additional research is required to evaluate the efficacy of internet-based treatment compared to telephone and face-to-face delivery. Regardless of the type or mode of delivery, research aimed at exploring the mechanisms of action is necessary for IPT interventions. This will aid in further refining IPT interventions, improving outcomes, and determining whether the intervention is applicable in additional settings.

Studies exploring various techniques for keeping women engaged in treatment for extended periods of time are warranted to ensure that perinatal women can complete the full IPT intervention. This will take into consideration an individual’s preference for treatment. Longitudinal studies of different intervention models (varying in length and delivery) and social support are needed. More research into how IPT interventions can be implemented as a part of routine prenatal care is needed.

4.4. Clinical Implications

There is a large body of research that demonstrates the effectiveness of treatments for depression and anxiety during the perinatal period (Milgrom, Negri, Gemmill, McNeil, & Martin, 2005; Nillni et al., 2018; L. E. Sockol, 2018; L. E. Sockol et al., 2013) [,,,]. Given that there is strong evidence for and no difference in the effectiveness for prevention and treatment of various psychotherapies allows for women to determine which psychotherapy they would choose. This choice may also be influenced by the mental health services offered through the trained therapists in their area. Additionally, the decision on whether to use pharmacotherapy in addition to psychotherapy during the perinatal period is complex and requires the consideration of many factors, including the effects of untreated maternal mood and/or medication exposure on both maternal and fetal outcomes. Clinical discussion making around mental health treatment options would benefit from thoughtful conversations between clinicians and the perinatal women as well as their families as no one treatment works for everyone.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review provides evidence that IPT is an effective intervention for the prevention and treatment of psychological distress in women during their pregnancy and postpartum period. This review also highlights the need for robust, high quality RCTs exploring different intervention models for women during the perinatal period.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/22/8421/s1.

Author Contributions

K.S.B. and D.K. conceived the review. All authors, K.S.B., E.M.C., M.K.M., A.W., D.M., S.S., K.A.H., and D.L. designed the protocol. K.A.H. and K.S.B. conducted the preliminary searches. All authors reviewed the manuscript, read, and approved the final manuscript. D.K. is the guarantor of the review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

K.S.B. is supported by the Graduate Studentship Award from the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute and Faculty of Nursing, University of Calgary. E.M.C. is supported by the Eyes High Doctoral Scholarship, University of Calgary.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the support of the University of Calgary, Faculty of Nursing, and the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

List of Abbreviations

| ANRQ | Antenatal Risk Questionnaire |

| AQS | Attachment Style Questionnaire |

| BAI | Beck Anxiety Inventory |

| BDI | Beck Depression Inventory |

| BDI-II | Beck Depression Inventory |

| Brief-STAI | Brief State-Trait Anxiety Inventory |

| CAGE-AID | Questionnaire for Drug and Alcohol Addiction Screening |

| CBT | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy |

| CBQ | Child Behavior Questionnaire |

| CES-D | Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale |

| CIDI | Composite International Diagnostic Interview |

| CNM-IPT | Certified Nurse-Midwife Telephone Administered Interpersonal Psychotherapy |

| CSQ | Cooper Survey Questionnaire |

| CTS2 | Revised Conflict Tactic Scale |

| CWS | Cambridge Worry Scale |

| DAS | Dyadic Adjustment Scale |

| DASS-21 | Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale—21 items |

| DIS | Diagnostic Interview Schedule |

| DLC | Difficult Life Circumstances |

| DSM-IV | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition |

| DSM-IV-NP | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, non patient version |

| EAS | Emotional Availability Scale |

| ECR | Experiences in Close Relationships Scale |

| ECR-R | Experiences in Close Relationships Revised Scale |

| EPDS | Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale |

| EPDS-P | Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for Partners |

| EFCT | Emotional Focused Couples Therapy |

| EPHPP | Effective Public Health Practice Project |

| GAF | Global Assessment of Functioning |

| GHQ | General Health Questionnaire |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| HAM-A | Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale |

| HAM-D | Hamilton Depression Rating Scale |

| HSC | Hopkins Symptoms Checklist |

| HRSD | Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (also written as HAM-D) |

| IBQ | Infant Behavior Questionnaire |

| ICD | International Classification of Disease |

| ICMJE | International Committee of Medical Journal Editors |

| IDD | Inventory of Diagnose Depression |

| IIP | Inventory of Interpersonal Problems |

| IPT | Interpersonal Psychotherapy |

| IPT-G | Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Groups |

| LIFE | Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation |

| LIFE-R | Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation Revised |

| LQ | Leverton Questionnaire |

| MAI | Maternal Attachment Inventory |

| MCMI-II | Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory |

| MDD | Major Depressive Disorder |

| MFB | Mindfulness Based |

| MINI | MINI-International Neuropsychiatric Interview |

| M-ITG | Mother-Infant Therapy Group |

| MSSS | Maternity Social Support Scale |

| OT | Open Trial |

| PLC-C | Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist–Civilian Version |

| PES | Peripartum Events Scale |

| PHQ | Patient Health Questionnaire |

| PHQ-9 Questionnaire Revised | Patient Health |

| PPAQ | Postpartum Adjustment Questionnaire |

| PPD | Postpartum Depression |

| PRISMA-P | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses Protocols |

| PSI | Parenting Stress Index |

| PSOC | Parenting Sense of Competence Scale |

| PSOC-E | Parenting Sense of Competence with Efficacy Scale |

| PSR | Psychiatric Status Rating |

| QRT | Quasi-Randomized Controlled Trial |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| ROSE | Reach out, Stand Strong |

| SAS | Social Adjustment Scale |

| SAS-SR | Social Adjustment Scale Self Report |

| SCID | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM |

| SCID-I | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM I |

| SCID-IV | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM IV |

| SCL-90 | Symptoms Checklist 90 Questions |

| SSQ-R | School Situations Questionnaire-Revised |

| STAI | State-Trait Anxiety Inventory |

| STAXI | State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory |

| SUD | Substance Use Disorders |

| TAU | Treatment as Usual |

| TSR | Treatment Services Review |

| WSAS | Weinberg Screening Affective Scales |

| WLC | Waitlist Control |

References

- Huizink, A.C.; Menting, B.; De Moor, M.H.M.; Verhage, M.L.; Kunseler, F.C.; Schuengel, C.; Oosterman, M. From prenatal anxiety to parenting stress: A longitudinal study. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2017, 20, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashford, M.T.; Olander, E.K.; Ayers, S. Computer-or web-based interventions for perinatal mental health: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 197, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Göbel, A.; Stuhrmann, L.Y.; Harder, S.; Schulte-Markwort, M.; Mudra, S. The association between maternal-fetal bonding and prenatal anxiety: An explanatory analysis and systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 239, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.V.; Shao, L.; Howell, H.; Lin, H.; Yonkers, K.A. Perinatal depression and birth outcomes in a Healthy Start project. Matern. Child Health J. 2011, 15, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biaggi, A.; Conroy, S.; Pawlby, S.; Pariante, C.M. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 191, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomfohr, L.M.; Buliga, E.; Letourneau, N.L.; Campbell, T.S.; Giesbrecht, G.F. Trajectories of Sleep Quality and Associations with Mood during the Perinatal Period. Sleep 2015, 38, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingston, D.; Austin, M.P.; Hegadoren, K.; McDonald, S.; Lasiuk, G.; McDonald, S.; Heaman, M.; Biringer, A.; Sword, W.; Giallo, R.; et al. Study protocol for a randomized, controlled, superiority trial comparing the clinical and cost- effectiveness of integrated online mental health assessment-referral-care in pregnancy to usual prenatal care on prenatal and postnatal mental health and infant health and development: The Integrated Maternal Psychosocial Assessment to Care Trial (IMPACT). Trials 2014, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughnan, S.A.; Newby, J.M.; Haskelberg, H.; Mahoney, A.; Kladnitski, N.; Smith, J.; Black, E.; Holt, C.; Milgrom, J.; Austin, M.-P. Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy (iCBT) for perinatal anxiety and depression versus treatment as usual: Study protocol for two randomised controlled trials. Trials 2018, 19, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, A.; Pearson, R.M.; Goodman, S.H.; Rapa, E.; Rahman, A.; McCallum, M.; Howard, L.M.; Pariante, C.M. Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet 2014, 384, 1800–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasheen, C.; Richardson, G.A.; Fabio, A. A systematic review of the effects of postnatal maternal anxiety on children. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2010, 13, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, S.M.; Briggs-Gowan, M.J.; Storfer-Isser, A.; Carter, A.S. Persistence of Maternal Depressive Symptoms throughout the Early Years of Childhood. J. Women’s Health 2009, 18, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giallo, R.; Bahreinian, S.; Brown, S.; Cooklin, A.; Kingston, D.; Kozyrskyj, A. Maternal depressive symptoms across early childhood and asthma in school children: Findings from a Longitudinal Australian Population Based Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, M.P.; Kingston, D. Psychosocial assessment and depression screening in the perinatal period: Benefits, challenges and implementation. In JoInt. Care of Parents and Infants in Perinatal Psychiatry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 167–195. [Google Scholar]

- Woolhouse, H.; Brown, S.; Krastev, A.; Perlen, S.; Gunn, J. Seeking help for anxiety and depression after childbirth: Results of the Maternal Health Study. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2009, 12, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, M.P.; Frilingos, M.; Lumley, J.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D.; Roncolato, W.; Acland, S.; Saint, K.; Segal, N.; Parker, G. Brief antenatal cognitive behaviour therapy group intervention for the prevention of postnatal depression and anxiety: A randomised controlled trial. J. Affect. Disord. 2008, 105, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuijpers, P.; Geraedts, A.S.; van Oppen, P.; Andersson, G.; Markowitz, J.C.; van Straten, A. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depression: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2011, 168, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donker, T.; Bennett, K.; Bennett, A.; Mackinnon, A.; van Straten, A.; Cuijpers, P.; Christensen, H.; Griffiths, K.M. Internet-delivered interpersonal psychotherapy versus internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for adults with depressive symptoms: Randomized controlled noninferiority trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangier, U.; Schramm, E.; Heidenreich, T.; Berger, M.; Clark, D.M. Cognitive therapy vs interpersonal psychotherapy in social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2011, 68, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, M.G. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed antepartum women: A pilot study. Am. J. Psychiatry 1997, 154, 1028–1030. [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli, M.G.; Endicott, J. Controlled clinical trial of interpersonal psychotherapy versus parenting education program for depressed pregnant women. Am. J. Psychiatry 2003, 160, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon, A.R.; Ceccotti, N.; Hynan, L.S.; Shivakumar, G.; Johnson, N.; Jarrett, R.B. Proof of concept: Partner-Assisted Interpersonal Psychotherapy for perinatal depression. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2012, 15, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, S.; O’Hara, M.W. Interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression: A treatment program. J. Psychother. Pr. Res. 1995, 4, 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart, S. Interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2012, 19, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuart, S.; Clark, E. The treatment of postpartum depression with interpersonal psychotherapy and interpersonal counseling. Sante Ment. Que. 2008, 33, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuart, S.; Robertson, M. Interpersonal Psychotherapy 2E A Clinician’s Guide; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster, C.A.; Gold, K.J.; Flynn, H.A.; Yoo, H.; Marcus, S.M.; Davis, M.M. Risk factors for depressive symptoms during pregnancy: A systematic review. Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 2010, 202, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilkington, P.D.; Rominov, H.; Milne, L.C.; Giallo, R.; Whelan, T.A. Partners to Parents: Development of an online intervention for enhancing partner support and preventing perinatal depression and anxiety. Adv. Ment. Health 2017, 15, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, S. What is IPT? The basic principles and the inevitability of change. J. Contemp. Psychother. 2008, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrona, C.E.; Russell, D.W. Autonomy promotion, responsiveness, and emotion regulation promote effective social support in times of stress. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 13, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R.; Knoll, N. Functional roles of social support within the stress and coping process: A theoretical and empirical overview. Int. J. Psychol. 2007, 42, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurullah, A.S. Received and provided social support: A review of current evidence and future directions. Am. J. Health Stud. 2012, 27, 173–188. [Google Scholar]

- Champion, L. Social relationships and social roles. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2012, 19, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; McKay, G. Social support, stress and the buffering hypothesis: A theoretical analysis. Handb. Psychol. Health 1984, 4, 253–267. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koszycki, D.; Bisserbe, J.-C.; Blier, P.; Bradwejn, J.; Markowitz, J. Interpersonal psychotherapy versus brief supportive therapy for depressed infertile women: First pilot randomized controlled trial. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2012, 15, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, J.H. Women’s attitudes, preferences, and perceived barriers to treatment for perinatal depression. Birth 2009, 36, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingston, D.; Biringer, A.; McDonald, S.W.; Heaman, M.I.; Lasiuk, G.C.; Hegadoren, K.M.; McDonald, S.D.; van Zanten, S.V.; Sword, W.; Kingston, J.J.; et al. Preferences for Mental Health Screening Among Pregnant Women: A Cross-Sectional Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 49, e35–e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, J.H.; Tyer-Viola, L. Detection, treatment, and referral of perinatal depression and anxiety by obstetrical providers. J. Women’s Health 2010, 19, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingston, D.; Austin, M.P.; Heaman, M.; McDonald, S.; Lasiuk, G.; Sword, W.; Giallo, R.; Hegadoren, K.; Vermeyden, L.; van Zanten, S.V.; et al. Barriers and facilitators of mental health screening in pregnancy. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 186, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, K.M.; Farrer, L.; Christensen, H. The efficacy of internet interventions for depression and anxiety disorders: A review of randomised controlled trials. Med. J. Aust. 2010, 192, S4–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sockol, L.E. A systematic review and meta-analysis of interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal women. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 232, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; Group, P.-P. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, K.S.; Charrois, E.M.; Mughal, M.K.; Wajid, A.; McNeil, D.; Stuart, S.; Hayden, K.A.; Kingston, D. Interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal women: A systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, A.; Grote, N.K.; Russo, J.; Lohr, M.J.; Jung, H.; Rouse, C.E. Collaborative care for perinatal depression among socioeconomically disadvantaged women: Adverse neonatal birth events and treatment response. Psychiatr. Serv. 2017, 68, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, A.; Baetz, M.; Schwartz, L.; Balbuena, L.; Muhajarine, N. Antenatal group therapy improves worry and depression symptoms. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2014, 51, 226–231. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H. Addressing maternal mental health needs in Singapore. Psychiatr Serv. 2011, 62, 102–103. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, J.P. Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Postnatal Anxiety Disorder. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2015, 25, 88–94. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, R.; Tluczek, A.; Wenzel, A. Psychotherapy for postpartum depression: A preliminary report. Am J. Orthopsychiatry 2003, 73, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crockett, K.; Zlotnick, C.; Davis, M.; Payne, N.; Washington, R. A depression preventive intervention for rural low-income African-American pregnant women at risk for postpartum depression. Archives Women’s Mental Health 2008, 11, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deans, C.; Reay, R.; Buist, A. Addressing the mother–baby relationship in interpersonal psychotherapy for depression: An overview and case study. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2016, 34, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.L.; Grigoriadis, S.; Zupancic, J.; Kiss, A.; Ravitz, P. Telephone-based nurse-delivered interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression: Nationwide randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 2020, 216, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, T.; Deeds, O.; Diego, M.; Hernandez-Reif, M.; Gauler, A.; Sullivan, S. Benefits of combining massage therapy with group interpersonal psychotherapy in prenatally depressed women. J. Bodyw. Mov Ther. 2009, 13, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, T.; Diego, M.; Delgado, J.; Medina, L. Peer support and interpersonal psychotherapy groups experienced decreased prenatal depression, anxiety and cortisol. Early Hum. Dev. 2013, 89, 621–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forman, D.R.; O’hara, M.W.; Stuart, S.; Gorman, L.L.; Larsen, K.E.; Coy, K.C. Effective treatment for postpartum depression is not sufficient to improve the developing mother–child relationship. Dev. Psychopathol. 2007, 19, 585–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.L.; Chan, S.W.-C.; Li, X.; Chen, S.; Hao, Y. Evaluation of an interpersonal-psychotherapy-oriented childbirth education programme for Chinese first-time childbearing women: A randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 1208–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.L.; Chan, S.W.; Sun, K. Effects of an interpersonal-psychotherapy-oriented childbirth education programme for Chinese first-time childbearing women at 3-month follow up: Randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.L.; Luo, S.Y.; Chan, S.W. Interpersonal psychotherapy-oriented program for Chinese pregnant women: Delivery, content, and personal impact. Nurs. Health Sci. 2012, 14, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.L.; Sun, K.; Chan, S.W. Social support and parenting self-efficacy among Chinese women in the perinatal period. Midwifery 2014, 30, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.L.; Xie, W.; Yang, X.; Chan, S.W. Effects of an interpersonal-psychotherapy-oriented postnatal programme for Chinese first-time mothers: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, N.K.; Bledsoe, S.E.; Swartz, H.A.; Frank, E. Feasibility of providing culturally relevant, brief interpersonal psychotherapy for antenatal depression in an obstetrics clinic: A pilot study. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2004, 14, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, N.K.; Swartz, H.A.; Geibel, S.L.; Zuckoff, A.; Houck, P.R.; Frank, E. A randomized controlled trial of culturally relevant, brief interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2009, 60, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, N.K.; Katon, W.J.; Russo, J.E.; Lohr, M.J.; Curran, M.; Galvin, E. Collaborative Care for Perinatal Depression in Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Women: A Randomized Trial. Depress Anxiety 2015, 32, 821–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, N.K.; Simon, G.E.; Russo, J.; Lohr, M.J.; Carson, K.; Katon, W. Incremental benefit-cost of MOMcare: Collaborative care for perinatal depression among economically disadvantaged women. Psychiatr Serv. 2017, 68, 1164–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajiheidari, M.; Sharifi, M.; Khorvash, F. The effect of interpersonal psychotherapy on marriage adaptive and postpartum depression in isfahan. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 4, 256–261. [Google Scholar]

- Kao, J.C.; Johnson, J.E.; Todorova, R.; Zlotnick, C. The Positive Effect of a Group Intervention to Reduce Postpartum Depression on Breastfeeding Outcomes in Low-Income Women. Int. J. Group Psychother. 2015, 65, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klier, C.M.; Muzik, M.; Rosenblum, K.L.; Lenz, G. Interpersonal psychotherapy adapted for the group setting in the treatment of postpartum depression. J. Psychother Pract Res. 2001, 10, 124–131. [Google Scholar]

- Kozinszky, Z.; Dudas, R.B.; Devosa, I.; Csatordai, S.; Tóth, É.; Szabó, D. Can a brief antepartum preventive group intervention help reduce postpartum depressive symptomatology? Psychother. Psychosom. 2012, 81, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenze, S.N.; Rodgers, J.; Luby, J. A pilot, exploratory report on dyadic interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal depression. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2015, 18, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenze, S.N.; Potts, M.A. Brief Interpersonal Psychotherapy for depression during pregnancy in a low-income population: A randomized controlled trial. J. Affect Disord. 2017, 165, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, S.S.; Lam, T.H. Group antenatal intervention to reduce perinatal stress and depressive symptoms related to intergenerational conflicts: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 1391–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moel, J.E.; Buttner, M.M.; O’Hara, M.W.; Stuart, S.; Gorman, L. Sexual function in the postpartum period: Effects of maternal depression and interpersonal psychotherapy treatment. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2010, 13, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulcahy, R.; Reay, R.E.; Wilkinson, R.B.; Owen, C. A randomised control trial for the effectiveness of group Interpersonal Psychotherapy for postnatal depression. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2010, 13, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylen, K.J.; O’Hara, M.W.; Brock, R.; Moel, J.; Gorman, L.; Stuart, S. Predictors of the longitudinal course of postpartum depression following interpersonal psychotherapy. J. Consult Clin Psychol. 2010, 78, 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hara, M.W.; Stuart, S.; Gorman, L.L.; Wenzel, A. Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000, 57, 1039–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hara, M.W.; Pearlstein, T.; Stuart, S.; Long, J.D.; Mills, J.A.; Zlotnick, C. A placebo controlled treatment trial of sertraline and interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression. J. Affect Disord. 2019, 245, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearlstein, T.B.; Zlotnick, C.; Battle, C.L.; Stuart, S.; O’Hara, M.W.; Price, A.B. Patient choice of treatment for postpartum depression: A pilot study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006, 9, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posmontier, B.; Neugebauer, R.; Stuart, S.; Chittams, J.; Shaughnessy, R. Telephone-Administered Interpersonal Psychotherapy by Nurse-Midwives for Postpartum Depression. J. Midwifery Womens Health. 2016, 61, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posmontier, B.; Bina, R.; Glasser, S.; Cinamon, T.; Styr, B.; Sammarco, T. Incorporating interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression into social work practice in Israel. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2019, 29, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reay, R.; Fisher, Y.; Robertson, M.; Adams, E.; Owen, C. Group interpersonal psychotherapy for postnatal depression: A pilot study. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2006, 9, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, M.G.; Endicott, J.; Leon, A.C.; Goetz, R.R.; Kalish, R.B.; Brustman, L.E. A controlled clinical treatment trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed pregnant women at 3 New York City sites. J. Clin Psychiatry 2013, 74, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, M.G.; Endicott, J.; Goetz, R.R. Increased breastfeeding rates in black women after a treatment intervention. Breastfeed Med. 2013, 8, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotnick, C.; Johnson, S.L.; Miller, I.W.; Pearlstein, T.; Howard, M. Postpartum depression in women receiving public assistance: Pilot study of an interpersonal-therapy-oriented group intervention. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 638–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotnick, C.; Miller, I.W.; Pearlstein, T.; Howard, M.; Sweeney, P. A preventive intervention for pregnant women on public assistance at risk for postpartum depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 1443–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlotnick, C.; Capezza, N.M.; Parker, D. An interpersonally based intervention for low-income pregnant women with intimate partner violence: A pilot study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011, 14, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlotnick, C.; Tzilos, G.; Miller, I.; Seifer, R.; Stout, R. Randomized controlled trial to prevent postpartum depression in mothers on public assistance. J. Affect Disord. 2016, 189, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, H.; Ciliska, D.; Dobbins, M. Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies; Effective Public Health Practice Project; McMaster University: Toronto, OT, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brunton, R.J.; Dryer, R.; Saliba, A.; Kohlhoff, J. Pregnancy anxiety: A systematic review of current scales. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 176, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mughal, M.K.; Giallo, R.; Arnold, P.D.; Kehler, H.; Bright, K.; Benzies, K.; Wajid, A.; Kingston, D. Trajectories of maternal distress and risk of child developmental delays: Findings from the All Our Families (AOF) pregnancy cohort. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 248, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, T. Prenatal anxiety effects: A review. Infant Behav. Dev. 2017, 49, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, K.; Becker, G. Maternal emotional health before and after birth matters. In Late Preterm Infants; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Egan, S.J.; Kane, R.T.; Winton, K.; Eliot, C.; McEvoy, P.M. A longitudinal investigation of perfectionism and repetitive negative thinking in perinatal depression. Behav. Res. 2017, 97, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowndes, T.A.; Egan, S.J.; McEvoy, P.M. Efficacy of brief guided self-help cognitive behavioral treatment for perfectionism in reducing perinatal depression and anxiety: A randomized controlled trial. Cogn. Behav. 2019, 48, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standeven, L.R.; Nestadt, G.; Samuels, J. Genetics of perinatal obsessive–compulsive disorder: A focus on past genetic studies to inform future inquiry. In Biomarkers of Postpartum Psychiatric Disorders; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 95–109. [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz, J.L.; Hellberg, S.N.; Abramowitz, J.S. Phenomenology of perinatal obsessive–compulsive disorder. In Biomarkers of Postpartum Psychiatric Disorders; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Marmarosh, C.; Holtz, A.; Schottenbauer, M. Group Cohesiveness, Group-Derived Collective Self-Esteem, Group-Derived Hope, and the Well-Being of Group Therapy Members. Group Dyn. 2005, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuijpers, P.; Donker, T.; Weissman, M.M.; Ravitz, P.; Cristea, I.A. Interpersonal psychotherapy for mental health problems: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2016, 173, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, J.C.; Hansen, J.L.; Simonsen, S.; Simonsen, E.; Gluud, C. Effects of cognitive therapy versus interpersonal psychotherapy in patients with major depressive disorder: A systematic review of randomized clinical trials with meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses. In Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE): Quality-assessed Reviews [Internet]; Centre for Reviews and Dissemination: Helingston, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers, P.; Van Straten, A.; Andersson, G.; Van Oppen, P. Psychotherapy for depression in adults: A meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 76, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nillni, Y.I.; Mehralizade, A.; Mayer, L.; Milanovic, S. Treatment of depression, anxiety, and trauma-related disorders during the perinatal period: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 66, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Shea, G.; Spence, S.H.; Donovan, C.L. Group versus individual interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2015, 43, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Sockol, L.E.; Epperson, C.N.; Barber, J.P. A meta-analysis of treatments for perinatal depression. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 31, 839–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sockol, L.E.; Epperson, C.N.; Barber, J.P. Preventing postpartum depression: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 1205–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J.H.; Santangelo, G. Group treatment for postpartum depression: A systematic review. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2011, 14, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misri, S.; Reebye, P.; Corral, M.; Milis, L. The use of paroxetine and cognitive-behavioral therapy in postpartum depression and anxiety: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2004, 65, 1236–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, J.; Negri, L.M.; Gemmill, A.W.; McNeil, M.; Martin, P.R. A randomized controlled trial of psychological interventions for postnatal depression. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 44, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).