Network Analysis of the Social Environment Relative to Preference for and Tolerance of Exercise Intensity in CrossFit Gyms

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Do the preference and tolerance scores of a person’s social connections relate to their own preference and tolerance scores after controlling for other factors including demographic information, duration of time as a CrossFit member, weekly class attendance rates, depressive symptoms, personality, and sense of community variables (i.e., is there evidence of social influence on preference and tolerance scores among CrossFit members)?

- What individual and social factors, including preference and tolerance scores, are associated with social connections present within CrossFit networks?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographic/Background Information

2.2.2. Preference and Tolerance

2.2.3. Personality

2.2.4. Depressive Symptoms

2.2.5. Sense of Community

2.2.6. Sociometric Network Data

2.3. Analytic Strategy

Model Specification

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Linear Network Autocorrelation Models

3.3. Exponential Random Graph Models

3.3.1. Structural Properties

3.3.2. Homophily

3.3.3. Non-Directional Covariates

3.3.4. Sender/Receiver Covariates

4. Discussion

4.1. Social Environment → Preference and Tolerance

4.2. Preference and Tolerance → Social Connections

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arem, H.; Moore, S.C.; Patel, A.; Hartge, P.; Berrington de Gonzalez, A.; Visvanathan, K.; Campbell, P.T.; Freedman, M.; Weiderpass, E.; Adami, H.O.; et al. Leisure Time Physical Activity and Mortality: A Detailed Pooled Analysis of the Dose-Response Relationship. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinney, J.; Lithwick, D.J.; Morrison, B.N.; Nazzari, H.; Isserow, S.H.; Heilbron, B.; Krahn, A. The health benefits of physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness. B. C. Med. J. 2016, 58, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Kapteyn, A.; Banks, J.; Hamer, M.; Smith, J.P.; Steptoe, A.; van Soest, A.; Koster, A.; Htay Wah, S. What they say and what they do: Comparing physical activity across the USA, England and the Netherlands. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2018, 72, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, J.M.; Welk, G.J.; Beyler, N.K. Physical Activity in U.S. Adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 40, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Physical Activity and Adults; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 29–42.

- Trost, S.G.; Owen, N.; Bauman, A.E.; Sallis, J.F.; Brown, W. Correlates of adults’ participation in physical activity: Review and update. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002, 34, 1996–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, K.M.; Patel, P.M.; O’Neal, J.L.; Heinrich, B.S. High-intensity compared to moderate-intensity training for exercise initiation, enjoyment, adherence, and intentions: An intervention study. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feito, Y.; Heinrich, K.M.; Butcher, S.J.; Poston, W.S.C. High-Intensity Functional Training (HIFT): Definition and Research Implications for Improved Fitness. Sports 2018, 6, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, K.M.; Spencer, V.; Fehl, N.; Carlos Poston, W.S. Mission Essential Fitness: Comparison of Functional Circuit Training to Traditional Army Physical Training for Active Duty Military. Mil. Med. 2012, 177, 1125–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, K.M.; Becker, C.; Carlisle, T.; Gilmore, K.; Hauser, J.; Frye, J.; Harms, C.A. High-intensity functional training improves functional movement and body composition among cancer survivors: A pilot study. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2015, 24, 812–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murawska-Cialowicz, E.; Wojna, J.; Zuwala-Jagiello, J. Crossfit training changes brain-derived neurotrophic factor and irisin levels at rest, after wingate and progressive tests, and improves aerobic capacity and body composition of young physically active men and women. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. Off. J. Pol. Physiol. Soc. 2015, 66, 811–821. [Google Scholar]

- Feito, Y.; Hoffstetter, W.; Serafini, P.; Mangine, G. Changes in body composition, bone metabolism, strength, and skill-specific performance resulting from 16-weeks of HIFT. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, J.; Sales, A.; Carlson, L.; Steele, J. A comparison of the motivational factors between CrossFit participants and other resistance exercise modalities: A pilot study. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2017, 57, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, K.M.; Carlisle, T.; Kehler, A.; Cosgrove, S.J. Mapping Coaches’ Views of Participation in CrossFit to the Integrated Theory of Health Behavior Change and Sense of Community. Fam. Community Health 2017, 40, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claudino, J.G.; Gabbett, T.J.; Bourgeois, F.; de Sá Souza, H.; Miranda, R.C.; Mezêncio, B.; Soncin, R.; Cardoso Filho, C.A.; Bottaro, M.; Hernandez, A.J.; et al. CrossFit Overview: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med. Open 2018, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, M.S.; Gagnon, L.R.; Vukelich, A.; Brown, S.E.; Nelon, J.L.; Prochnow, T. Social networks, group exercise, and anxiety among college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2019, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, M.N.; Mackintosh, S.F.; Hillier, S.L.; Bryan, J. Regular group exercise is associated with improved mood but not quality of life following stroke. PeerJ 2014, 2, e331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lautner, S.C.; Patterson, M.S.; Graves-Boswell, T.; Spadine, M.N.; Heinrich, K.M. Exploring the social side of CrossFit: A qualitative study. Ment. Health Soc. Incl. in press. [CrossRef]

- Lovell, G.P.; Gordon, J.A.R.; Mueller, M.B.; Mulgrew, K.; Sharman, R. Satisfaction of Basic Psychological Needs, Self-Determined Exercise Motivation, and Psychological Well-Being in Mothers Exercising in Group-Based Versus Individual-Based Contexts. Health Care Women Int. 2016, 37, 568–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteman-Sandland, J.; Hawkins, J.; Clayton, D. The role of social capital and community belongingness for exercise adherence: An exploratory study of the CrossFit gym model. J. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 1545–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, A.G.; Petruzzello, S.J. Why do they do it? Differences in high-intensity exercise-affect between those with higher and lower intensity preference and tolerance. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2020, 47, 101521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekkekakis, P.; Thome, J.; Petruzzello, S.J.; Hall, E.E. The Preference for and Tolerance of the Intensity of Exercise Questionnaire: A psychometric evaluation among college women. J. Sports Sci. 2008, 26, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekkekakis, P.; Hall, E.E.; Petruzzello, S.J. Some like It Vigorous: Measuring Individual Differences in the Preference for and Tolerance of Exercise Intensity. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2005, 27, 350–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiamonte, B.A.; Kraemer, R.R.; Chabreck, C.N.; Reynolds, M.L.; McCaleb, K.M.; Shaheen, G.L.; Hollander, D.B. Exercise-induced hypoalgesia: Pain tolerance, preference and tolerance for exercise intensity, and physiological correlates following dynamic circuit resistance exercise. J. Sports Sci. 2017, 35, 1831–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caraça Smirmaul, B.P.; Ekkekakis, P.; Teixeira, I.P.; Nakamura, P.M.; Kokubun, E. Preference for and Tolerance of the Intensity of Exercise questionnaire: Brazilian Portuguese version. Braz. J. Kinanthr. Hum. Perform. 2015, 17, 550–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.E.; Petruzzello, S.J.; Ekkekakis, P.; Miller, P.C.; Bixby, W.R. Role of Self-Reported Individual Differences in Preference for and Tolerance of Exercise Intensity in Fitness Testing Performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 2443–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, J.D.; Close, G.L.; MacLaren, D.P.M.; Gregson, W.; Drust, B.; Morton, J.P. High-intensity interval running is perceived to be more enjoyable than moderate-intensity continuous exercise: Implications for exercise adherence. J. Sports Sci. 2011, 29, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekkekakis, P.; Parfitt, G.; Petruzzello, S.J. The Pleasure and Displeasure People Feel When they Exercise at Different Intensities: Decennial Update and Progress towards a Tripartite Rationale for Exercise Intensity Prescription. Sports Med. 2011, 41, 641–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parfitt, G.; Rose, E.A.; Burgess, W.M. The psychological and physiological responses of sedentary individuals to prescribed and preferred intensity exercise. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godley, J. Preference or propinquity? The relative contribution of selection and opportunity to friendship homophily in college. Connections 2008, 1, 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Steglich, C.; Snijders, T.A.B.; Pearson, M. Dynamic Networks and Behavior: Separating Selection from Influence. Sociol. Methodol. 2010, 40, 329–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, M.; Smith-Lovin, L.; Cook, J.M. Birds of a Feather: Homophily in Social Networks. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2001, 27, 415–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, G.R. Declaration of Helsinki—The World’s Document of Conscience and Responsibility. South. Med. J. 2014, 107, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The STROBE Initiative The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies*. Bull. World Health Organ. 2007, 85, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, M.S.; Goodson, P. Social network analysis for assessing college-aged adults’ health: A systematic review. J. Am. Coll. Health 2018, 67, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valente, T.W. Social Networks and Health: Models, Methods, and Applications; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gile, K.J.; Handcock, M.S. Analysis of Networks with Missing Data with Application to the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Available online: https://rss.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/rssc.12184 (accessed on 3 September 2019).

- McQuaid, D.; Barton, J.; Campbell, E. Researchers BEWARE! Attrition and Nonparticipation at Large. J. Burn Care Rehabil. 2003, 24, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, S.P.; Carley, K.M.; Krackhardt, D. On the robustness of centrality measures under conditions of imperfect data. Soc. Netw. 2006, 28, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costenbader, E.; Valente, T.W. The stability of centrality measures when networks are sampled. Soc. Netw. 2003, 25, 283–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, P.E.L.; Babcock, B.; Cillessen, A.H.N.; Crick, N.R. The Effects of Participation Rate on the Internal Reliability of Peer Nomination Measures: Participation and Sociometric Reliability. Soc. Dev. 2013, 22, 609–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekkekakis, P.; Hall, E.E.; Petruzzello, S.J. Variation and homogeneity in affective responses to physical activity of varying intensities: An alternative perspective on dose—Response based on evolutionary considerations. J. Sports Sci. 2005, 23, 477–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, S.D.; Rentfrow, P.J.; Swann, W.B. A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. J. Res. Personal. 2003, 37, 504–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A. Relationship among Four Big Five Measures of Different Length. Psychol. Rep. 2008, 102, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research, 3rd ed.; John, O.P., Robins, R.W., Pervin, L.A., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-1-59385-836-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, P. The Handbook of Psychological Testing; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-1-315-81227-4. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, S.A.; Hampson, S.E. Measuring the Big Five with single items using a bipolar response scale. Eur. J. Personal. 2005, 19, 373–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Strine, T.W.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W.; Berry, J.T.; Mokdad, A.H. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J. Affect. Disord. 2009, 114, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarason, S.B. The Psychological Sense of Community: Prospects for a Community Psychology, 1st ed.; The Jossey-Bass Behavioral Science Series; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1974; ISBN 978-0-87589-216-0. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, S.; Kerwin, S.; Walker, M. Examining Sense of Community in Sport: Developing the Multidimensional ‘SCS’ Scale. J. Sport Manag. 2013, 27, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM. IMB SPSS Statistics for Windows; IRB Corporation: Armonk, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Leenders, R.T.A.J. Modeling social influence through network autocorrelation: Constructing the weight matrix. Soc. Netw. 2002, 24, 21–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochnow, T.; Patterson, M.S.; Hartnell, L.; Umstattd Meyer, M.R. Depressive symptoms associations with online and in person networks in an online gaming community: A pilot study. Ment. Health Rev. J. 2020, 25, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochnow, T.; van Woudenberg, T.J.; Patterson, M.S. Network Effects on Adolescents’ Perceived Barriers to Physical Activity. J. Phys. Act. Health 2020, 17, 889–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handcock, M.S.; Hunter, D.R.; Butts, C.T.; Goodreau, S.M.; Morris, M. Statnet: Software Tools for the Statistical Modeling of Network Data. J. Stat Softw. 2008, 24, 1548–7660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team R. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Exponential Random Graph Models for Social Networks: Theory, Methods, and Applications; Structural Analysis in the Social Sciences; Lusher, D., Koskinen, J., Robins, G., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-521-19356-6. [Google Scholar]

- Fleeson, W.; Jolley, S. A Proposed Theory of the Adult Development of Intraindividual Variability in Trait-Manifesting Behavior. In Handbook of Personality Development; Mroczek, D.K., Little, T.D., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Fleeson, W. Situation-Based Contingencies Underlying Trait-Content Manifestation in Behavior. J. Personal. 2007, 75, 825–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritzler, S.; Krasko, J.; Luhmann, M. Inside the happy personality: Personality states, situation experience, and state affect mediate the relation between personality and affect. J. Res. Personal. 2020, 85, 103929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrance, C.; Tsofliou, F.; Clark, C. Adherence to community based group exercise interventions for older people: A mixed-methods systematic review. Prev. Med. 2016, 87, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fien, S.; Henwood, T.; Climstein, M.; Keogh, J.W.L. Feasibility and benefits of group-based exercise in residential aged care adults: A pilot study for the GrACE programme. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogg, T.; Roberts, B.W. The Case for Conscientiousness: Evidence and Implications for a Personality Trait Marker of Health and Longevity. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 45, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, M.L.; Friedman, H.S. Do conscientious individuals live longer? A quantitative review. Health Psychol. 2008, 27, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogg, T. Conscientiousness, the transtheoretical model of change, and exercise: A neo-socioanalytic integration of trait and social-cognitive frameworks in the prediction of behavior. J. Personal. 2008, 76, 775–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duckworth, A. Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance; Scribner: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, J.; Pritschet, B.L.; Cutton, D.M. Grit, conscientiousness, and the transtheoretical model of change for exercise behavior. J. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, S.P. Centrality and network flow. Soc. Netw. 2005, 27, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L. Centrality in social networks: Conceptual clarification. Soc. Netw. 1979, 1, 215–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammrath, L.K.; Armstrong, B.F.; Lane, S.P.; Francis, M.K.; Clifton, M.; McNab, K.M.; Baumgarten, O.M. What predicts who we approach for social support? Tests of the attachment figure and strong ties hypotheses. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 118, 481–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, D.; Esterling, K.; Lazer, D. The Strength of Strong Ties: A Model of Contact-Making in Policy Networks with Evidence from U.S. Health Politics. Ration. Soc. 2003, 15, 411–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, M.R.; Araújo, C.L.P.; Reichert, F.F.; Siqueira, F.V.; da Silva, M.C.; Hallal, P.C. Gender differences in leisure-time physical activity. Int. J. Public Health 2007, 52, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aral, S.; Nicolaides, C. Exercise contagion in a global social network. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penedo, F.J.; Dahn, J.R. Exercise and well-being: A review of mental and physical health benefits associated with physical activity. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2005, 18, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, N. Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

| Gym 1 | Gym 2 | Gym 3 | Total Sample | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD | %, n | M ± SD | %, n | M ± SD | %, n | M ± SD | %, n | |

| Age | 25.74 ± 10.22 | 43.58 ± 19.05 | 33.07 ± 9.52 | 35.51 ± 12.21 | ||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 58.6%, n = 34 | 58.1%, n = 18 | 70.4%, n = 76 | 65.0%, n = 128 | ||||

| Male | 41.4%, n = 24 | 41.9%, n = 13 | 29.6%, n = 32 | 35.0%, n = 69 | ||||

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 81%, n = 47 | 87.1%, n = 27 | 91.7%, n = 99 | 87.8%, n = 173 | ||||

| Black | 0%, n = 0 | 0%, n = 0 | 0%, n = 0 | 0%, n = 0 | ||||

| Hispanic | 1.7%, n = 1 | 0%, n = 0 | 0%, n = 0 | 0.5%, n = 1 | ||||

| Asian | 1.7%, n = 1 | 0%, n = 0 | 0%, n = 0 | 0.5%, n = 1 | ||||

| Native American | 1.7%, n = 1 | 0%, n = 0 | 0%, n = 0 | 0.5%, n = 1 | ||||

| Multiracial | 3.4%, n = 2 | 3.2%, n = 1 | 0%, n = 0 | 1.5%, n = 3 | ||||

| Other | 6.9%, n = 4 | 3.2%, n = 1 | 2.8%, n = 3 | 4.1%, n = 8 | ||||

| Prefer not to say | 3.4%, n = 2 | 0%, n = 0 | 0%, n = 0 | 1.0%, n = 2 | ||||

| Classes per Week | 4.48 ± 1.14 | 3.55 ± 1.18 | 3.91 ± 1.23 | 4.02 ± 1.24 | ||||

| <1/week | 1.7%, n = 1 | 0%, n = 0 | 0.9%, n = 1 | 1.0%, n = 2 | ||||

| 1/week | 0%, n = 0 | 0%, n = 0 | 4.6%, n = 5 | 2.5%, n = 5 | ||||

| 2/week | 3.4%, n = 2 | 22.6%, n = 7 | 2.8%, n = 3 | 6.1%, n = 12 | ||||

| 3/week | 8.6%, n = 5 | 29.0%, n = 9 | 25.0%, n = 27 | 20.8%, n = 41 | ||||

| 4/week | 31.0%, n = 18 | 22.6%, n = 7 | 38.0%, n = 41 | 33.5%, n = 66 | ||||

| 5/week | 39.7%, n = 23 | 22.6%, n = 7 | 18.5%, n = 20 | 25.4%, n = 50 | ||||

| >5/week | 15.5%, n = 9 | 3.2%, n = 1 | 10.2%, n = 11 | 10.7%, n = 21 | ||||

| CrossFit Member | ||||||||

| <6 months | 19%, n = 11 | 3.2%, n = 1 | 9.3%, n = 10 | 11.2%, n = 22 | ||||

| 6 months–1 year | 5.2%, n = 3 | 22.6%, n = 7 | 9.3%, n = 10 | 10.2%, n = 20 | ||||

| >1–2 years | 12.1%, n = 7 | 9.7%, n = 3 | 23.1%, n = 25 | 17.8%, n = 35 | ||||

| >2–3 years | 29.3%, n = 3 | 12.9%, n = 4 | 14.8%, n = 16 | 18.8%, n = 37 | ||||

| >3–4 years | 20.7%, n = 12 | 29.0%, n = 9 | 24.1%, n = 26 | 23.9%, n = 47 | ||||

| 4+ years | 13.8%, n = 8 | 22.6%, n = 7 | 19.4%, n = 21 | 18.3%, n = 36 | ||||

| Preference | 13.30 ± 2.67 | 12.40 ± 2.84 | 14.17 ± 2.42 | 13.64 ± 2.63 | ||||

| Tolerance | 13.78 ± 2.12 | 14.19 ± 2.46 | 13.60 ± 2.77 | 13.74 ± 2.54 | ||||

| Depressive Symptoms | 4.19 ± 2.89 | 3.06 ± 2.83 | 4.29 ± 4.01 | 4.07 ± 3.55 | ||||

| Severe (+10) | 1.7%, n = 1 | 0%, n = 0 | 8.4%, n = 9 | 5.0%, n = 10 | ||||

| Personality | ||||||||

| Extraversion | 6.57 ± 2.61 | 6.47 ± 2.18 | 6.57 ± 2.48 | 6.55 ± 2.46 | ||||

| Agreeableness | 7.93 ± 1.29 | 8.15 ± 1.97 | 7.72 ± 1.91 | 7.85 ± 1.89 | ||||

| Conscientiousness | 9.03 ± 1.65 | 9.29 ± 1.14 | 9.06 ± 1.22 | 9.09 ± 1.34 | ||||

| Emotional Stability | 7.64 ± 2.16 | 7.63 ± 2.11 | 7.65 ± 2.10 | 7.65 ± 2.11 | ||||

| Openness to Experiences | 7.83 ± 1.37 | 8.45 ± 1.39 | 8.06 ± 1.59 | 8.05 ± 1.51 | ||||

| Sense of Community | ||||||||

| Administrative | 3.13 ± 0.21 | 3.03 ± 0.33 | 3.11 ± 0.26 | 3.11 ± 0.25 | ||||

| Consideration | ||||||||

| Common Interest | 2.74 ± 0.36 | 2.71 ± 0.46 | 2.84 ± 0.36 | 2.78 ± 0.38 | ||||

| Equity in Administrative | 2.76 ± 0.30 | 2.57 ± 0.39 | 2.74 ± 0.42 | 2.72 ± 0.39 | ||||

| Decisions | ||||||||

| Leadership Opportunities | 2.16 ± 0.53 | 2.42 ± 0.66 | 2.24 ± 0.61 | 2.24 ± 0.60 | ||||

| Social Spaces | 2.85 ± 0.28 | 2.63 ± 0.46 | 2.79 ± 0.33 | 2.78 ± 0.35 | ||||

| Competition | 2.70 ± 0.43 | 2.41 ± 0.73 | 2.70 ± 0.49 | 2.65 ± 0.53 | ||||

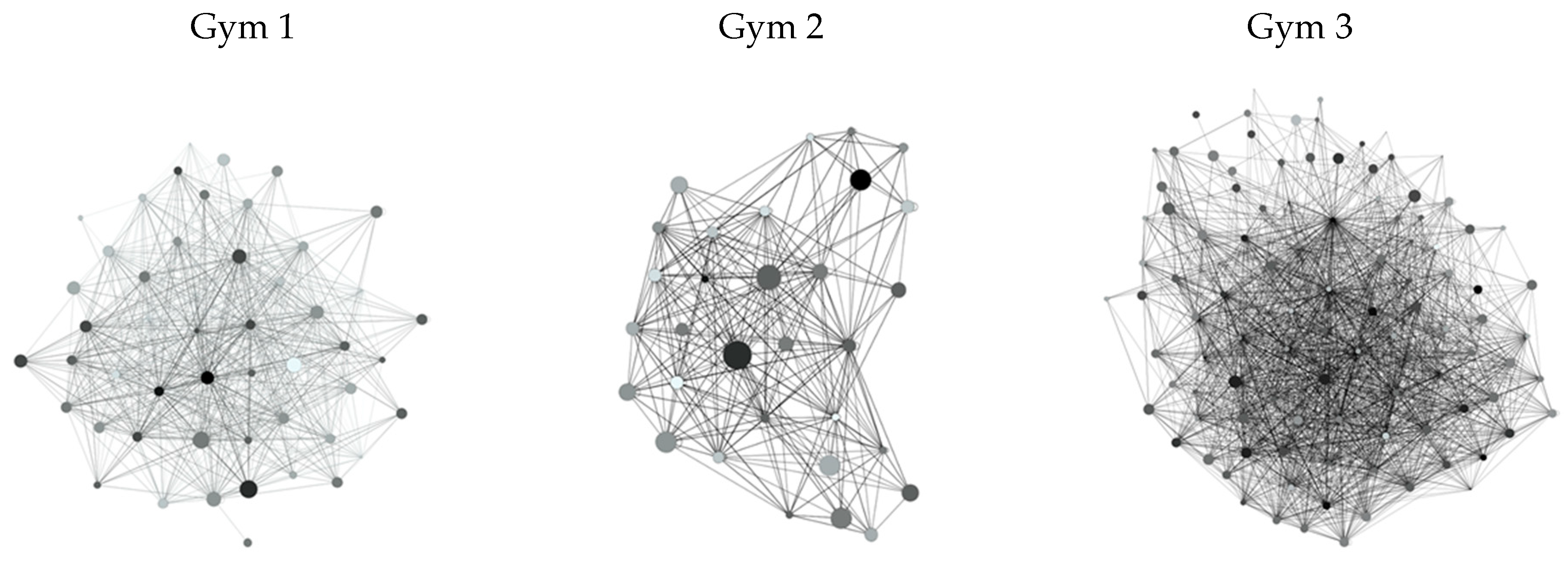

| Network Descriptives | ||||||||

| Network Nodes, Edges | 58, 1233 | 31, 384 | 98, 2736 | |||||

| Network Degree | 41.97 ± 24.98 | 23.94 ± 11.66 | 49.94 ± 37.88 | |||||

| Network Density | 0.37 | 0.41 | 0.23 | |||||

| Covariate | Gym 1: R2 = 0.35 *** | Gym 2: R2 = 0.55 *** | Gym 3: R2 = 0.18 *** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |

| Gender (ref: female) | 0.28 | 0.82 | −3.04 *** | 0.64 | −0.35 | 0.63 |

| Age | −0.05 | 0.23 | 0.06 * | 0.03 | 0.50 | 0.03 |

| Classes per Week | 0.86 * | 0.40 | 0.69 * | 0.33 | −0.57 | 0.28 |

| CrossFit Member | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0.14 | 0.41 | 0.58 | 0.19 |

| Personality | ||||||

| Extraversion | 0.03 | 0.15 | −0.32 | 0.21 | 1.46 | 0.12 |

| Agreeableness | −0.02 | 0.21 | −0.23 | 0.33 | 0.45 | 0.17 |

| Conscientiousness | 0.29 | 0.22 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 1.22 | 0.25 |

| Emotional Stability | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.28 | −0.29 | 0.16 |

| Openness to Experiences | 0.40 | 0.31 | 0.51 | 0.28 | −0.21 | 0.20 |

| Depressive Symptoms | 0.25 | 0.13 | −0.54 ** | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.08 |

| Sense of Community | ||||||

| Administrative Consideration | 3.97 ** | 1.97 | 0.92 | 1.66 | 0.48 | 1.31 |

| Common Interest | −1.83 | 1.29 | 3.93 ** | 1.45 | 0.82 | 1.12 |

| Equity in Administrative Decisions | 2.09 | 1.460 | 5.28 *** | 1.21 | 0.93 | 0.94 |

| Leadership Opportunities | −1.23 | 0.92 | 1.92 * | 0.83 | −1.03 | 0.56 |

| Social Spaces | −0.08 | 1.76 | 2.79 | 1.91 | −0.32 | 1.23 |

| Competition | 1.21 | 1.14 | 0.26 | 0.81 | 2.44 * | 0.71 |

| Network Effects | 0.14 *** | 0.03 | 0.21 *** | 0.05 | 0.05 ** | 0.03 |

| Covariate | Gym 1: R2 = 0.22 *** | Gym 2: R2 = 0.40 *** | Gym 3: R2 = 0.23 *** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |

| Gender (ref: female) | 0.10 | 0.67 | −1.24 *** | 0.45 | −0.37 | 0.50 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Classes per Week | 0.47 | 0.33 | 0.41 * | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.22 |

| CrossFit Member | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.06 | 0.23 | 0.14 | 0.10 |

| Personality | ||||||

| Extraversion | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.51 *** | 0.14 | −0.04 | 0.10 |

| Agreeableness | 0.08 | 0.13 | −0.47 * | 0.21 | −0.09 | 0.14 |

| Conscientiousness | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.68 * | 0.29 | 0.55 ** | 0.20 |

| Emotional Stability | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.50 * | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.12 |

| Openness to Experiences | 0.09 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.16 |

| Depression | −0.02 | 0.11 | −0.35 ** | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.06 |

| Sense of Community | ||||||

| Administrative Consideration | 1.13 * | 0.50 | 0.79 ** | 0.27 | 0.38 | 0.27 |

| Common Interest | −0.21 | 0.35 | 0.58 | 0.32 | −0.02 | 0.31 |

| Equity in Administrative Decisions | 0.23 | 0.63 | 0.86 * | 0.43 | −0.19 | 0.38 |

| Leadership Opportunities | 0.08 | 0.30 | −0.12 | 0.15 | −0.03 | 0.11 |

| Social Spaces | 0.63 | 0.71 | 0.96 * | 0.40 | 0.06 | 0.49 |

| Competition | −0.26 | 0.34 | −0.24 | 0.18 | 0.31 | 0.20 |

| Network Effects | 0.19 ** | 0.02 | 0.17 *** | 0.06 | 0.07 ** | 0.02 |

| Parameter | Gym 1 | Gym 2 | Gym 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |

| Structural | ||||||

| Edges | 12.70 *** | 1.16 | 13.07 *** | 3.31 | 3.08 *** | 0.63 |

| Reciprocity | 6.90 *** | 0.69 | 2.34 *** | 0.27 | 2.45 *** | 0.08 |

| Transitivity | 1.98 ** | 0.20 | 5.24 ** | 2.03 | 0.69 *** | 0.21 |

| Homophily | ||||||

| Gender | −0.40 | 0.45 | 0.24 * | 0.12 | 0.12 ** | 0.05 |

| Preference | −0.59 *** | 0.11 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 * | 0.01 |

| Tolerance | 1.28 *** | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.06 *** | 0.01 |

| Non-Directional Covariates | ||||||

| Age | 0.25 *** | 0.02 | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 *** | 0.00 |

| CrossFit Member | 1.74 *** | 0.17 | 0.16 *** | 0.05 | 0.20 *** | 0.01 |

| Classes per Week | 1.84 *** | 0.19 | 0.16 ** | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Extraversion | −1.43 *** | 0.13 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 * | 0.01 |

| Conscientiousness | −0.24 * | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.06 | −0.12 *** | 0.01 |

| Agreeableness | 2.09 *** | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.12 *** | 0.01 |

| Emotional Stability | 1.67 *** | 0.14 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.07 *** | 0.01 |

| >Openness to Experiences | 1.42 *** | 0.17 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.06 *** | 0.01 |

| Administrative Consideration | 6.71 *** | 0.31 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.16 *** | 0.02 |

| Common Interest | 0.38 | 0.21 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.15 *** | 0.02 |

| Equity in Administrative Decisions | 1.64 *** | 0.46 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.10 *** | 0.03 |

| Leadership Opportunities | 2.48 *** | 0.19 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.06 *** | 0.01 |

| Social Spaces | 3.89 *** | 0.51 | −0.08 | 0.08 | 0.28 *** | 0.03 |

| Competition | −2.68 *** | 0.29 | 0.05 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.01 |

| Sender/Receiver Covariates | ||||||

| Depressive Symptoms (In) | −0.99 *** | 0.09 | −0.14 ** | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Depressive Symptoms (Out) | 1.09 *** | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 *** | 0.01 |

| Preference (In) | 0.23 *** | 0.07 | 0.07 * | 0.04 | −0.00 | 0.01 |

| Preference (Out) | 0.67 ** | 0.07 | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.03 ** | 0.01 |

| Tolerance (In) | −0.31 ** | 0.10 | −0.11 * | 0.05 | −0.03 * | 0.01 |

| Tolerance (Out) | −0.15 | 0.10 | 0.11 * | 0.05 | −0.00 | 0.01 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Patterson, M.S.; Heinrich, K.M.; Prochnow, T.; Graves-Boswell, T.; Spadine, M.N. Network Analysis of the Social Environment Relative to Preference for and Tolerance of Exercise Intensity in CrossFit Gyms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8370. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228370

Patterson MS, Heinrich KM, Prochnow T, Graves-Boswell T, Spadine MN. Network Analysis of the Social Environment Relative to Preference for and Tolerance of Exercise Intensity in CrossFit Gyms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(22):8370. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228370

Chicago/Turabian StylePatterson, Megan S., Katie M. Heinrich, Tyler Prochnow, Taylor Graves-Boswell, and Mandy N. Spadine. 2020. "Network Analysis of the Social Environment Relative to Preference for and Tolerance of Exercise Intensity in CrossFit Gyms" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 22: 8370. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228370

APA StylePatterson, M. S., Heinrich, K. M., Prochnow, T., Graves-Boswell, T., & Spadine, M. N. (2020). Network Analysis of the Social Environment Relative to Preference for and Tolerance of Exercise Intensity in CrossFit Gyms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8370. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228370