The Routines-Based Model Internationally Implemented

Abstract

1. Introduction

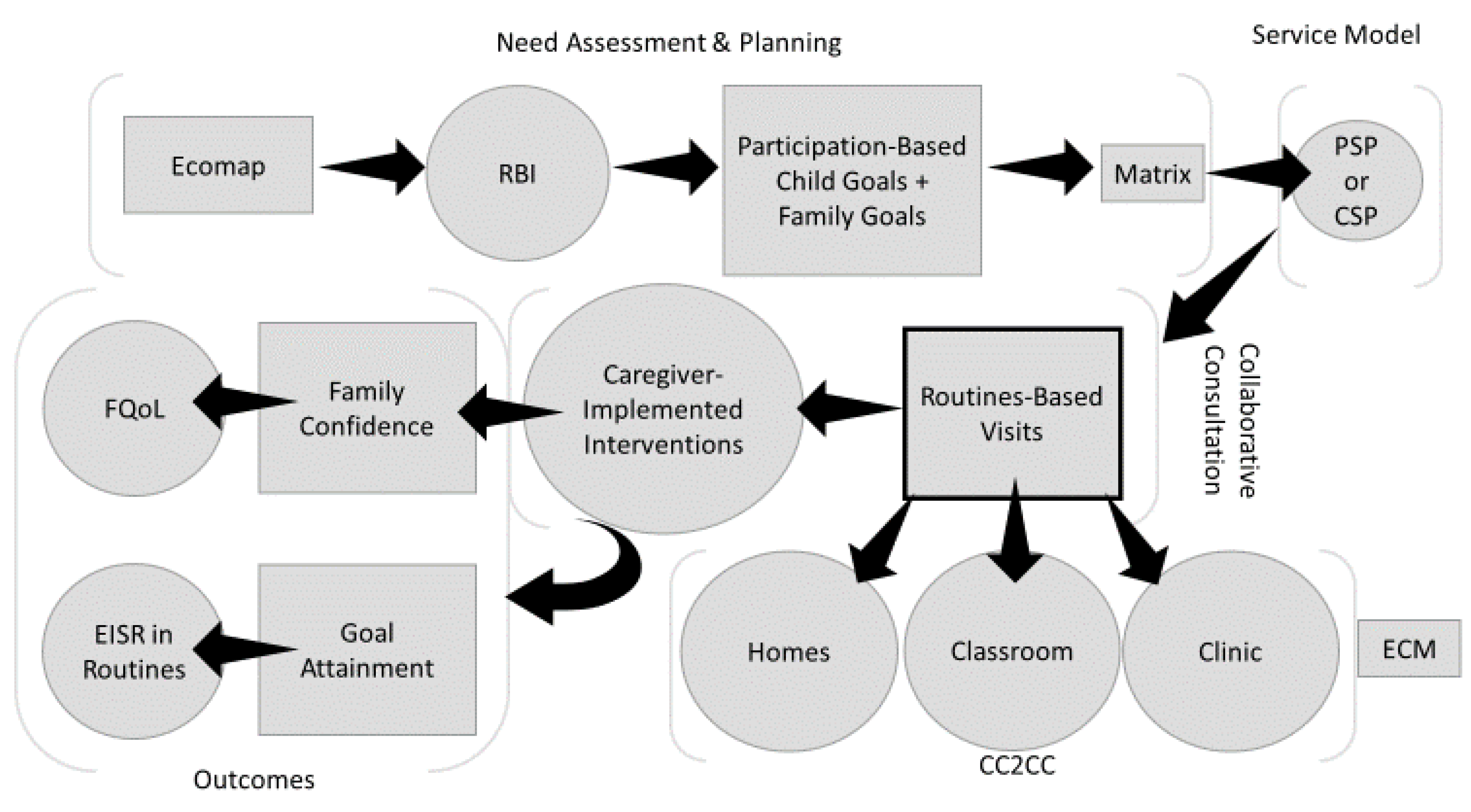

2. The Model

2.1. Needs Assessment and Intervention Plan Development

2.2. Consultative Approach to Early Intervention

2.3. Engagement Classroom Model

- Conducting an RBI to establish functional, routines-based goals;

- Incidental teaching to address all goals in all routines, by following the child’s lead and eliciting higher-order functioning;

- Integrated therapy, meaning specialists work with teachers in the classroom and never pull the child out;

- Zone defense schedule to arrange the room in zones, to organize the adults, and to decrease non-engagement time during transitions between activities;

- Incorporating Reggio Emilia concepts to promote children’s exploration, to encourage creativity in art, and to make the environment “provocative” and beautiful.

2.4. How the Model Became of Interest, Internationally

2.5. Why International Implementers Were Interested

2.6. Adopted Practices

2.7. RBI Plus

2.8. Family and Collaborative Consultation

2.9. Engagement Classroom Model

3. Implementation Challenges

3.1. Natural Environments

3.2. Primary Service Provider

3.3. Relinquishing Control to Families

3.4. Lack of Follow through

3.5. Organization and Reorganization

3.6. Checklists

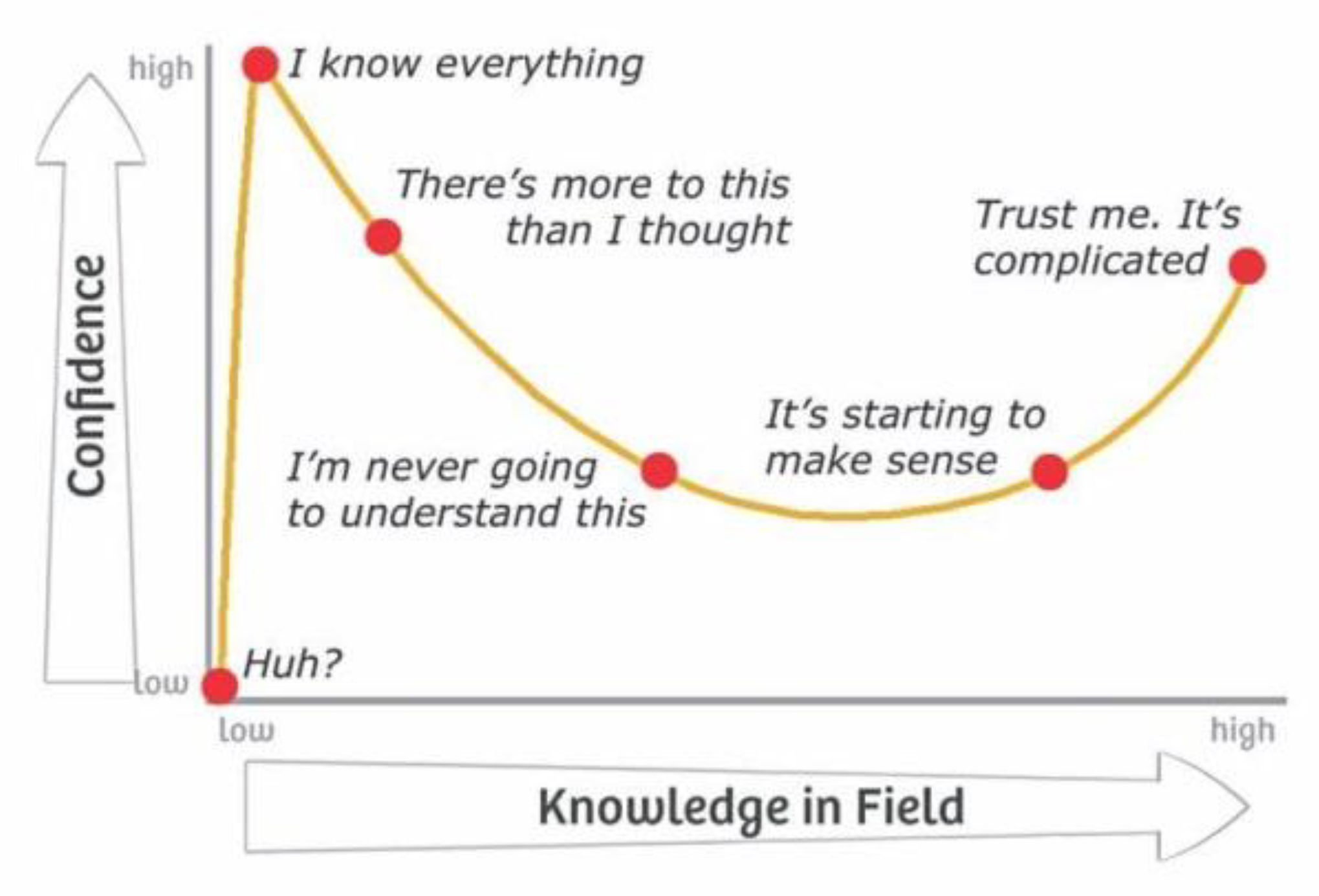

3.7. You Are Doing It Wrong

4. Implementation Successes

4.1. Professionals Feeling Useful

4.2. Families Feeling Confident

4.3. Children Functioning in Routines

5. Conclusions

5.1. Models Have to Be Adaptable

5.2. Some Principles and Practices Are Indeed Universal

5.3. Promoting a Global Perspective on Excellent Practices

5.4. Leadership

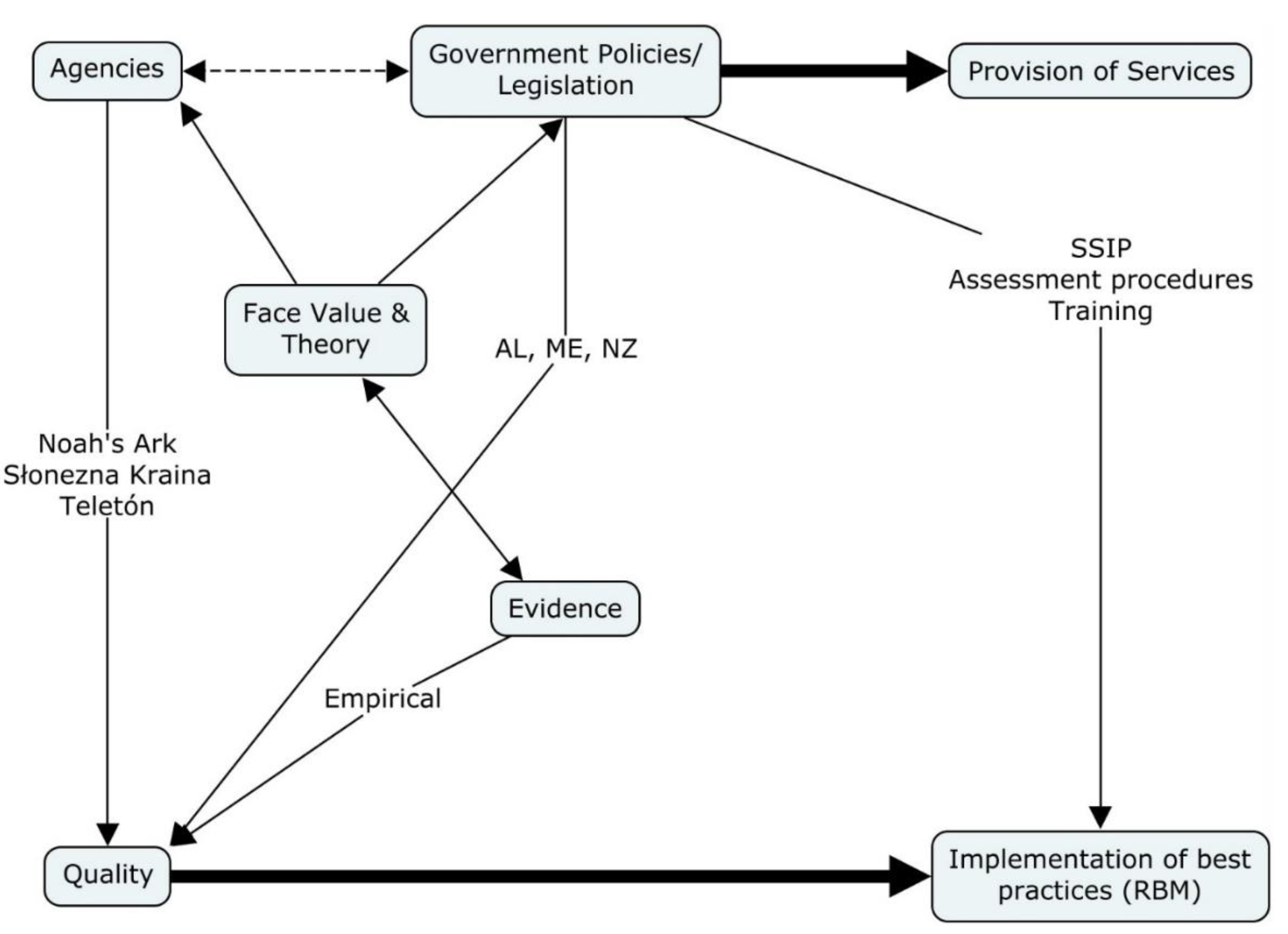

5.5. Framework Regarding Evidence, Policy, and Implementation

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McWilliam, R.A.; Trivette, C.M.; Dunst, C.J. Behavior engagement as a measure of the efficacy of early intervention. Anal. Int. Dev. Disabil. 1985, 5, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliam, R.A. Metanoia in early intervention: Transformation to a family-centered approach. Rev. Latinoam. Educ. Inclusiva 2016, 10, 155–173. [Google Scholar]

- Idol, L.; Nevin, A.; Paolucci-Whitcomb, P. Collaborative Consultation, 2nd ed.; PRO-ED: Austin, TX, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, L.A. Identifying families’ supports and other resources. In Working with Families of Young Children with Special Needs; McWilliam, R.A., Ed.; Brookes Publishing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2010; pp. 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliam, R.A. The Routines-Based Model for supporting speech and langauge. Logop. Foniatr. Audiol. 2016, 36, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.; Latham, G. Goal-setting theory. In Organizational Behavior 1: Essential Theories of Motivation and Leadership; Miner, J.B., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 159–183. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, J.J.; Lindeman, D.P. Gathering and giving information with families. Infants Young Child. 2008, 21, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, J.L.; Sawyer, L.B.; Campbell, P.H. Early intervention providers’ perspectives about implementing participation-based practices. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2011, 30, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliam, R.A. Routines-Based Early Intervention; Brookes Publishing Co.: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliam, R.A. Integration of therapy and consultative special education: A continuum in early intervention. Infants Young Child. 1995, 7, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliam, R.A.; Wolery, M.; Odom, S.L. Instructional perspectives in inclusive preschool classrooms. In Early Childhood Inclusion: Focus on Change; Guralnick, M.J., Ed.; Brookes Publishing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2001; pp. 503–530. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliam, R.A.; Casey, A.M. Engagement of Every Child in the Preschool Classroom; Paul H. Brookes Co.: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center. Idea Part C Profiles. 2014. Available online: https://osep.grads360.org/#program/idea-part-c-profiles (accessed on 17 July 2020).

- Grande, C.; Pinto, A.I. Estilos interactivos de educadoras do Ensino Especial em contexto de educação-de-infância. Psicol. Teor. Pesqui. 2009, 25, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessanha, M.; Pinto, A.I.; Barros, S. Influência da qualidade dos contextos familiar e de creche no envolvimento e no desenvolvimento da criança. Psicologia 2009, 23, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, A.M.; Pereira, A.P.; Carvalho, M.L. Oportunidades de aprendizagem para a crianca nos seus contextos de vida: Familia e comunidade/Child’s learning opportunities in natural environments: Family and community. Psicol. Rev. Assoc. Port. Psicol. 2003, 17, 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, A.-W.; Chao, M.; Liu, S. A randomized controlled trial of routines-based early intervention for children with or at risk for developmental delay. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 34, 3112–3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunst, C.J.; Johanson, C.; Trivette, C.M.; Hamby, D.W. Family-oriented early intervention policies and practices: Family-centered or not? Except. Child. 1991, 58, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McWilliam, R.A. Family-Centered Intervention Planning: A Routines-Based Approach; Communication Skill Builders: Tucson, AZ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrerizo de Diago, R.; López Pisón, P.; Navarro Callau, L. La Realidad Actual de la Atención Temprana en España; Real Patronato sobre Discapacidad: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Division for Early Childhood. DEC Recommended Practices in Early Intervention/Early Childhood Special Education. 2014. Available online: http://www.dec-sped.org/recommendedpractices (accessed on 16 July 2020).

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health: Children & Youth Version: ICF-CY; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, A.-W.; Liao, H.-F.; Granlund, M.; Simeonsson, R.J.; Kang, L.-J.; Pan, Y.-L. Linkage of ICF-CY codes with environmental factors in studies of developmental outcomes of infants and toddlers with or at risk for motor delays. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 36, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.-L.; Hwang, A.-W.; Simeonsson, R.J.; Lu, L.; Liao, H.-F. Utility of the early delay and disabilities code set for exploring the linkage between ICF-CY and assessment reports for children with developmental delay. Infants Young Child. 2019, 32, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliam, R.A.; Younggren, N. Measure of Engagement, Independece, and Social Relationships (MEISR™), Research Edition, Manual; Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, A.M.; McWilliam, R.A. The impact of checklist-based training on teachers’ use of the zone defense schedule. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2011, 44, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliam, R.A. (Ed.) Working with Families of Young Children with Special Needs; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliam, R.A. Families in Natural Environments Scale of Service Evaluation (FINESSE). In Routines-Based Early Intervention: Supporting Young Children and Their Families; McWilliam, R.A., Ed.; Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2010; pp. 212–220. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliam, R.A. Families in Natural Environments Scale of Service Evaluation (FINESSE II); University of North Carolina: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, A.M.; McWilliam, R.A. The STARE: Data collection without the scare. Young Except. Child. 2007, 11, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliam, R.A.; García Grau, P. Families in Early Intervention Quality of Life; The University of Alabama: Tuscaloosa, AL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Evidence-Based Intervention (EBI) Work Group. Theories of change and adoption of innovations: The evolving evidence-based intervention and practice movement in school psychology. Psychol. Sch. 2005, 42, 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliam, R.A. Assessing families’ needs with the routines-based interview. In Working with Families of Young Children with Special Needs; McWilliam, R.A., Ed.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 27–59. [Google Scholar]

- Associação Nacional de Intervenção Precoce. Práticas Recomendadas em Intervenção Precoce na Infância: Um Guia para Profissionais; Associação Nacional de Intervenção Precoce: Coimbra, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliam, R.A. The primary-service-provider model for home- and community-based services. Psicol. Rev. Assoc. Port. Psicol. 2003, 17, 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, J.J.; Wilcox, M.J.; Friedman, M.; Murch, T. Collaborative consultation in natural environments: Strategies to enhance family-centered supports and services. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 2011, 42, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliam, R.A.; Scarborough, A.A.; Kim, H. Adult interactions and child engagement. Early Educ. Dev. 2003, 14, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliam, R.A.; Scarborough, A.A.; Bagby, J.H.; Sweeney, A.L. Teaching Styles Rating Scale. Frank Porter Graham Child Development Center; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, A.M.; Freund, P.J.; McWilliam, R.A. Vanderbilt Ecological Congruence of Teaching Opportunities in Routines (VECTOR) Classroom Version; Vanderbilt Center for Child Development: Nashville, TN, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, H.-F.; Wu, P.-F. Early childhood inclusion in Taiwan. InfantsYoung Child. 2017, 30, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelden, M.L.; Rush, D.D. The Early Intervention Teaming Handbook: The Primary Service Provider Approach; Paul H. Brookes: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliam, R.A.; Garcia Grau, P. Towards Implementation of an early intervention model by a Paraguayan organization. Educação 2020, 43, e35700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, D. The Dunning-Kruger effect: On being ignorant of one’s own ignorance. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Olson, J.M., Zanna, M.P., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; Volume 44, pp. 247–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dargahwala, I. The Dunning Kruger Effect. 2019. Available online: https://dev.to/theiyd/the-dunning-kruger-effect-3cj2 (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- McWilliam, R.A.; Casey, A.M. More is Not Always Better: Research Findings; Presented at the International Conferene on Early Childhood (Division for Early Childhood of the Council for Exceptional Children), Chicago, IL, USA, 2004; Division for Early Childhood of the Council for Exceptional Children: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Boavida, T.; Aguiar, C.; McWilliam, R.A.; Correia, N. Effects of an in-service training program using the routines-based interview. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2016, 36, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliam, R.A. The top 10 mistakes in early intervention—And the solutions. Zero Three 2011, 31, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, A.-W. The Long-Term Effectiveness of Implementing a Participation-Based Early Intervention Program for Children with Developmental Delay: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial; Final Report (Project NO.: MOST-105-2314-B-182-012-); Unpublished Report; Ministry of Science and Technology: Taipei, Taiwan, 2017.

- Garcia Grau, P.; McWilliam, R.A.; Martínez-Rico, G.; Grau Sevilla, M.D. Factorial structure and internal conistency of a Spanish version of the Family Quality of Life (FaQoL) Scale. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2018, 13, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, A.A.; Powell, B.J.; Kohl, P.L.; Tabak, R.G.; Penalba, V.; Proctor, E.K.; Domenech-Rodriguez, M.M.; Cabassa, L.J. Cultural adaptation and implementation of evidence-based parent-training: A systematic review and critique of guiding evidence. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2015, 53, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunst, C.J.; Trivette, C.M. Using research evidence to inform and evaluate early childhood intervention practices. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2008, 29, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odom, S.L. The tie that binds evidence-based practice, implementation science, and outcomes for children. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2009, 29, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, B.G.; Cook, S.C. Thinking and Communicating Clearly about Evidence-Based Practices in Special Education; Division for Research, Council for Exceptional Children: Reston, VA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliam, R.A. Controversial practices: The need for a reacculturation of early intervention fields. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 1999, 19, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmau, M.; Balcells-Balcells, A.; Giné, C.; Cañadas, M.; Casas, O.; Salat, Y.; Farré, V.; Calaf, N. How to implement the family-centered model in early intervention. An. Psicol. 2017, 33, 641–651. [Google Scholar]

- Dunst, C.J.; Trivette, C.M. Let’s be PALS: An evidence-based approach to professional development. Infants Young Child. 2009, 22, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halle, T.; Metz, A.; Martinez-Beck, I. Applying Implementation Science in Early Childhood Programs and Systems; Paul H. Brookes Publishing Company: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ploeg, J.; Davies, B.; Edwards, N.; Gifford, W.; Miller, P.E. Factors influencing best-practice guideline implementation: Lessons learned from administrators, nursing staff, and project leaders. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2007, 4, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, A.I.; Grande, C.; Aguiar, C.; de Almeida, I.C.; Felgueiras, I.; Pimentel, J.S.; Serrano, A.M.; Carvalho, L.; Brandão, M.T.; Boavida, T.; et al. Early childhood intervention in Portugal: An overview based on the developmental systems model. Infants Young Child. 2012, 25, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchbank, A.M. The National Disability Insurance Scheme: Administrators’ Perspectives of Agency Transition to ‘User Pay’ for Early Intervention Service Delivery. Australas. J. Early Child. 2017, 42, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center. SSIP Phase III, Year 3 Analysis: Data. 2019. Available online: https://ectacenter.org/topics/ssip/ssip_p3.asp (accessed on 18 July 2020).

| Location | Exploration/Introduction | Installation/Implementation Planning | Extent of Implementation | Systemic/Cultural Barriers or Enhancers | Leadership |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | Presentations at national conference | Systematic planning at Melbourne/Canberra agency | 1 large agency in Melbourne and Canberra; sole trainer in Perth. Limited to RBI. | National Disability Insurance Scheme poses challenges; system already implementing PSP (key worker). | Agency head and key employees in Melbourne/Canberra. Individual PT in Perth. Both closely affiliated with national professional assoc. for early childhood intervention. |

| Canada | Presentations at Ontario mental health/early intervention conference | Systematic planning in York Region | Full model being implemented with dedicated coach. | Separate staff for home-based services from itinerant services, with different funding sources. | Regional leaders committed resources to certification of trainers. |

| New Zealand | Presentations followed by more intensive training sessions, primarily on RBI | Commitment by the Ministry of Education to implement the model | Whole model implemented but lapse in fidelity measures. | Coaches initially assigned, then withdrawn, now reinstated. | Initially, one of four regions, then national leadership. |

| Paraguay | Spanish leader in RBM implementation introduced large rehab agency to the model | After visits from the purveyor, the agency committed to implementation and sent a staff member to study with the purveyor | Implementing the RBI, without fidelity checks, and routines-based clinic visits. Planning home visits. | Rehab center philosophy, historically. Many families are rural, extremely poor, with domestic violence. | Leaders of the agency have invested in the model. Currently, one coach carries the load. |

| Poland | Shared platform at international conference led to presentation at university conference | Decision to found a preschool classroom using the Engagement Classroom Model (ECM) | Classroom built to accommodate the ECM, which includes RBI. | Highly therapy-focused approach to EI 0-6. Heavy governmental involvement in curriculum. | Owner, directors, faculty member, and coach all part of tight-knit group making decisions with the purveyor |

| Portugal | Purveyor had been teaching classes in Porto for years Students wrote grant to study engagement | National professional organization wrote manual based largely on RBM and offered training | Whole model is endorsed, although fidelity of implementation is unknown. | Two key players in implementation have died within one year. Difficult to achieve national consensus on approach to EI. First country outside U.S. to adopt practices. | Historically, very senior faculty member, then his acolytes and their students pushed implementation. Three leaders remain who could energize implementation. |

| Singapore | One developmental pediatrician invited purveyor to present Other agencies became interested | Three agencies showed interest in in-depth implementation and developed separate plans | Different agencies have committed to different amounts of the model. | Service historically have been in group sessions with therapists. Caregivers are often domestic workers. Culturally, education is formal, not play based. | In each of the three major agencies, leaders have pushed for continued professional development |

| Spain | Purveyor asked to consult and present in Valencia and for national audience | University-affiliated EI program adopted RBI. ECM not as successful | Training now occurring in some states, primarily on RBI. Confederation of agencies endorsed the model. | Confusion between the “family-centered model” and RBM has slowed implementation. Historically, EI provided in centers. | University faculty have led the charge, establishing model demonstration projects, conducting research, providing training to master’s students, and training programs. |

| Taiwan | Purveyor asked to make long presentations | Core group, primarily of PTs, interested in adopting and studying practices | Interest began with routines-based visits, then Engagement Classroom Model. One model demonstration preschool opened in Taichung. | Services have traditionally been hospital based. Demonstration preschool very different from most preschools. | Taiwanese professional org. for EI involved, researcher has led the way, PT leaders critical, core group of 7 trained in the RBI. |

| USA | The model was developed here and has increasingly become known through workshops, presentations, and certification institutes | Implementation plans have been developed in Multnomah County, OR; Maine, Missouri, Alabama, Colorado, Montana, etc. | Currently, Maine is the flagship implementer. Multnomah County, Alabama, and Mississippi are currently being trained to implement the full model. | History of year-by-year planning for personnel development has not led to a culture of implementation. Loathing of endorsing a model has resulted in stunted practice development. Culture of going after the latest bright, shiny object has meant little multi-year commitment. | Key individuals can be identified in each of the strong implementation sites. Always, the top person needs to be on board, if not the leader. Often, someone just under the leader is the flag bearer. Those flag bearers are more successful when they have co-conspirators. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McWilliam, R.A.; Boavida, T.; Bull, K.; Cañadas, M.; Hwang, A.-W.; Józefacka, N.; Lim, H.H.; Pedernera, M.; Sergnese, T.; Woodward, J. The Routines-Based Model Internationally Implemented. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8308. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228308

McWilliam RA, Boavida T, Bull K, Cañadas M, Hwang A-W, Józefacka N, Lim HH, Pedernera M, Sergnese T, Woodward J. The Routines-Based Model Internationally Implemented. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(22):8308. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228308

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcWilliam, R. A., Tânia Boavida, Kerry Bull, Margarita Cañadas, Ai-Wen Hwang, Natalia Józefacka, Hong Huay Lim, Marisú Pedernera, Tamara Sergnese, and Julia Woodward. 2020. "The Routines-Based Model Internationally Implemented" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 22: 8308. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228308

APA StyleMcWilliam, R. A., Boavida, T., Bull, K., Cañadas, M., Hwang, A.-W., Józefacka, N., Lim, H. H., Pedernera, M., Sergnese, T., & Woodward, J. (2020). The Routines-Based Model Internationally Implemented. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8308. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228308