“Kept in Check”: Representations and Feelings of Social and Health Professionals Facing Intimate Partner Violence (IPV)

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Intimate Partner Violence (IPV): The Violent Relationship and Its Consequences

1.2. Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

- a. The representation of the IPV phenomenon

- b. The representation of the woman victim of violence

- c. The representation of the perpetrator

- d. The intervention procedures (already used or suggested and not yet put into action)

- e. The influence of gender of the male and female professionals in the therapeutic relationship

3. Results

- 3.1.

- Representation of the effects of violence on the woman;

- 3.2.

- Representation of the woman victim of violence and her relational style;

- 3.3.

- Representation of the man inflicting violence and of his relational style;

- 3.4.

- Representation of the elements which keep the violent relationship alive;

- 3.5.

- Representation of the relationships between professionals, service providers, and users.

3.1. Representation of the Effects of Violence on the Woman

- Self-denigration of the woman. Often self-blame for the violence endured is reported in the woman, as well as difficulties in parenting roles, sometimes accompanied by a sense of guilt towards the children

(The woman victim of violence) “is a woman who doesn’t believe in herself, and doesn’t believe in her potential. She is a very fragile woman, with a lot of guilt, who tends to feel guilty about everything that happens, and so she keeps it all inside, she isolates herself on a social level because of her sense of shame”.(F, 31, Psychologist and Psychotherapist, workplace: Perpetrators’ shelter OLV—Oltre La Violenza)

- Difficulty in the parenting role. Professionals interviewed also described the women victims of violence as neglectful mothers: sucked into the violence endured, trapped in the dynamics of a controlling and dysfunctional relationship. They find it difficult to defend themselves and, consequently, to protect their children, whose needs they often do not see, because they are often acting in “emergency mode”.

“In the same way you can’t protect yourself, you can’t protect your children. Unfortunately, that’s it. I think there is a lack, in the person, of the ability to protect themselves…how can you then protect the young ones?”.(F, 39, Psychologist and Psychotherapist, Workplace: service combatting gender-based violence against women CAV—Centro Anti-Violenza)

3.2. Representation of the Woman Victim of Violence and her Relational Style

- Dependency. The words of the interviewees highlight above all the image of a dependent woman, with low self-esteem and autonomy limited to certain contexts (e.g., taking care of the children), or completely lacking.

“Often they are women who have problems with emotional dependence…so they have low self-esteem, very low...growing up with the idea that the man is the one who decides, who has a certain control, a certain power…”.(M, 49, Sociologist, workplace: Campania Region office)

- Denial. The professionals describe this when they find themselves facing women who appear, in their view, to be unaware of the violent situations they are experiencing:

“so maybe they don’t turn to a psychology service, or they do, but with great ambivalence, so then they decide not to go on with the process…”.(F, 42, Lawyer, workplace: Association Movimento Forense)

“so, when we run into some cases of violence and abuse that’s not recognized by the victims, that’s the support path to take, not only to allow the abuse to be seen, but also to recognize it as such, this is the first aspect”.(M, 46, Executive officer, workplace: Campania Region office for Equal Opportunities and Human Rights)

- Savior complex. The attitude of women victims of violence towards their partner, defined by the professionals as “Florence Nightingale syndrome”, is often connected to a sense of omnipotence with which these women face the dysfunctional relationship and its consequences:

“There’s always this thing “I’ll save you” that still works...even in us, with backgrounds in feminism, …that ‘savior’ is always there …lying in wait, so to say”.(F, 60, Sociologist, workplace: service combatting gender-based violence against women CAV)

3.3. Representation of the Man Inflicting Violence and of his Relational Style

- Manipulation and acting-out. The interviewers attribute to the perpetrator a relational style characterized by a marked tendency towards manipulation and the inability to engage with his own emotions or share them.

“They are very seductive men, tending towards being manipulative and fragile”.(F, 44, Social Worker, Service for Youth and Families)

- Fragility. As one psychologist states: “They are fragile and disconnected men, because being violent doesn’t mean being strong… I’ve always met very fragile men, so I think that the man who is a perpetrator of violence is often a person who, because he is so fragile, uses physical force to affirm himself over the other and to feel recognized” (F, 66, Psychologist and Psychotherapist; workplace: Perpetrators’ shelter OLV).

3.4. Representation of the Elements which Keep the Violent Relationship Alive

- Relational interlocking. The interviewees describe the relationship between victim and perpetrator as being based on strong complicity:

“… if a strong bond isn’t created then one doesn’t stay… I believe that we have to understand how far the complicity reaches”.(M, 70, Psychologist and Psychotherapist, Judiciary service)

“Often people who suffer from attachment dependency choose a partner who is also problematic… motivated by the intention of saving the other from his problems”.(M, 70, Psychologist and Psychotherapist, workplace: Judiciary service)

- The reciprocal omnipotence and destructivity of the violent couple. Furthermore, the interviewers add that the relationship dynamic is characterized by a sense of reciprocal omnipotence and deep destructivity. According to professionals, this starts to appear through denigration (sometimes reciprocal) and aggressive verbal interaction. According to some, it can affect all members of the family unit, even the children. In addition, it does not occur outside the walls of the home. The professionals talk about a “simulated normality” to outside eyes, on the part of both members of the couple.

“The woman feels like she’s really able to tolerate the violent man, so there’s a perverse dynamic related to the omnipotence… she is not aware of her feelings of omnipotence, so they are hard to access through awareness, but they are very dangerous, inducing the woman to tolerate every sort of violence”.(F, 31, Psychologist and Psychotherapist, workplace: Perpetrators’ shelter OLV)

“Because there’s no more pleasure, no more serenity, no more equilibrium, and then there’s the risk, indeed, not only of losing one’s life, the peak being femicide, but the loss of one’s mental wellbeing, because it’s a destructivity that actually becomes a threat to health and mental stability”.(F, 39, Psychologist, service combatting gender-based violence against women CAV)

3.5. The Representation of The Relationships between Professionals, Service Providers, and Users

- Holding the power. Power over women is reported to be one of the main dynamics on which men act.

“In these conflictual dynamics which then result in violence, power is activated…but as a perpetrator explained to me: ‘it is the power that I try to hold over others and the pleasure I get in holding this power, probably often linked to the fact that I, instead, am powerless over some of my emotions, some of my experiences’…”.(F, 66, Psychologist and Psychotherapist, workplace: Perpetrators’ shelter OLV)

- Taking over the other. Power and taking over the other leads to the man’s extreme control over the woman, but as described in an interview, in virtue of the extreme co-dependency of the couple, the woman also may become controlling. “The dynamics of control is implied, and it doesn’t always and only involve the partner who is violent towards the victim, because in a certain way even the victims have control or at least manipulate, … eh?” (M, 31, Psychologist, workplace: private practice).

- Active listening and lack of judgement, regardless of gender. Almost all the interviewees highlighted the difficulties, but also the absolute need for always maintaining a nonjudgmental attitude and for explorative listening, whether it be in the management of a woman victim of rape or the perpetrator.

“as a woman, mother, wife, I tend to see the tormenter, the monster… but, in any case from a professional standpoint we have consider that there is a human being with difficulties and experiences”.(F, 57, Psychologist, workplace: family services)

- Gender role in the relationship with the user. This regards the importance of the gender of the professional involved with the user. All the participants said it was fundamental that women victims of violence were welcomed and managed by female professionals (not only because this is required by law). As far as the relationship between professional and male perpetrator is concerned, pros and cons to both have been brought to light.

“it’s true that professionalism should not have a gender and all that, but for this type of problem it’s important, I think…there are women that clearly say ‘Just as well you’re a woman!’, so I think it is of great influence”.(F, 35, Psychologist and Psychotherapist, workplace: service fighting gender-based violence against women CAV)

“Violent men, when there’s a woman facing them, tend to undermine…for example, I’ve always been told ‘Yeah well, she’s allied with women… she’s an ally to women, surely she can’t understand me, she doesn’t defend me’!”.(F, 66, Psychologist and Psychotherapist, workplace. Perpetrators’ shelter OLV)

“In the male mentality there’s the idea that ‘I’m kind of a son’, no? ‘I’m my mother’s son, then I’m my wife’s son‘, no? I mean, it becomes a bit like that. And…. the fact that I find a woman in front to me, it represents the same pattern. I mean, I can fall into that thing, so much so that I... at least from the descriptions I’ve read, from what they tell me…’If I did it, I did it because she provoked me!’, no? It’s a bit like a child justifying himself to his mother”.(F, 61, Psychologist and Psychotherapist, workplace: Perpetrators’ shelter OLV)

“…the perpetrators aren’t greatly introspective people as you can imagine, on the contrary, they’re people with a tendency to act out to the max and have an attitude that’s almost saying, for example, at the moment I’m thinking of a person whose session was quite, not very simple, because he acted in an aggressive and arrogant manner”.(F, 66, Psychologist and Psychotherapist, workplace: Perpetrators’ shelter OLV)

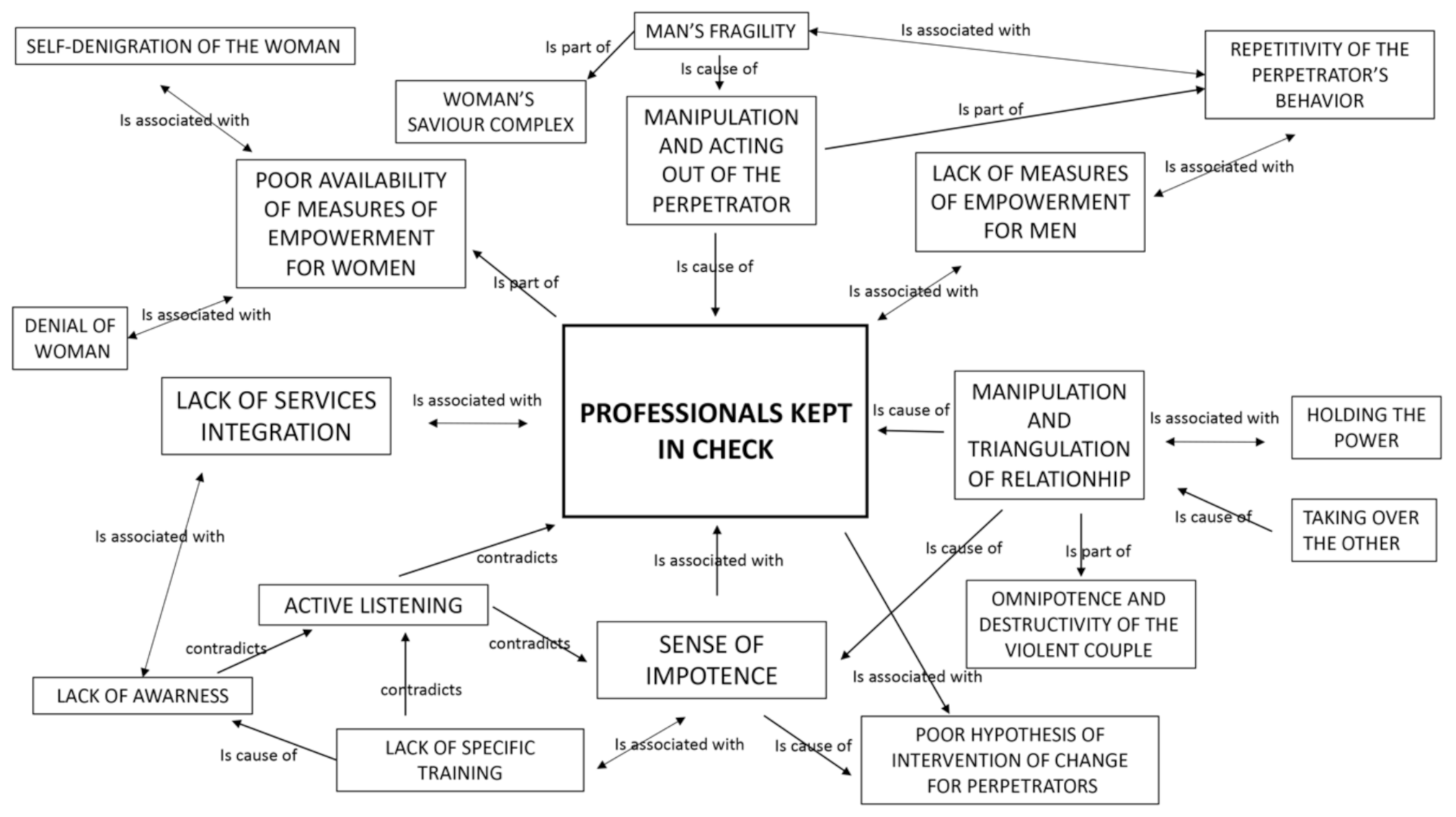

3.6. Core Category and Network

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Understanding and Addressing Violence against Women. Intimate Partner Violence. 2012. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/77432/WHO_RHR_12.36_eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Breiding, M.J.; Basile, K.; Smith, S.; Black, M.; Mahendra, R. Intimate Partner Violence Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements, Version 2.0; National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, R.S.; Bonomi, A.E.; Anderson, M.; Reid, R.J.; Dimer, J.A.; Carrell, D.; Rivara, F.P. Intimate partner violence: Prevalence, types, and chronicity in adult women. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2006, 30, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J. Shame and domestic violence: Treatment perspectives for perpetrators from self psychology and affect theory. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2004, 19, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldi, D.M.; Knoble, N.B.; Shortt, J.W.; Kim, H.K. A Systematic Review of Risk Factors for Intimate Partner Violence. Partner Abuse 2012, 3, 231–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creazzo, G.; Bianchi, L. Uomini che Maltrattano le Donne che fare? Sviluppare Strategie di Intervento con Uomini che Usano Violenza nelle Relazioni d’intimità [Men Who Abuse, Women What to Do? Develop Intervention Strategies with Men Who Use Violence in Intimate Relationships], 1st ed.; Carocci Faber: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ventimiglia, C. La Fiducia Tradita. Storie Dette e Raccontate di Partner Violenti, 1st ed.; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Magaraggia, S.; Cherubini, D. Uomini Contro le Donne? le Radici della Violenza Maschile, 1st ed.; UTET Università: Torino, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barbagli, M.; Saraceno, C. (Eds.) Lo Stato Delle Famiglie in Italia [The Status of Families in Italy], 1st ed.; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, W. The Myth of Male Power: Why Men Are the Disposable Sex, Part 1. New Male Stud. An Int. J. 2012, 1, 5–31. Available online: http://www.newmalestudies.com/ojs_v2/index.php/nms/article/viewFile/35/36 (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Hamberger, L.K.; Potente, T. Counseling heterosexual women arrested for domestic violence: Implications for theory and practice. Violence Vict. 1994, 9, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devries, K.M.; Mak, J.Y.; Bacchus, L.J.; Child, J.C.; Falder, G.; Petzold, M.; Astbury, J.; Watts, C.H. Intimate partner violence and incident depressive symptoms and suicide attempts: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. PLoS Med. 2013, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Moreno, C.; Watts, C. Violence against women: An urgent public health priority. Bull. World Health Organ. 2011, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA). Violence against Women: An EU-Wide Survey. 2014. Available online: https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2014/violence-against-women-euwide-survey (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- ISTAT. Commissione parlamentare di Inchiesta sul Femminicidio, Nonché su ogni forma di Violenza di Genere. Audizione del Presidente dell’Istituto Nazionale di Statistica Giorgio Alleva, 2017 [Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry into Femicide, as well as on every Form of Gender Violence. Hearing of the President of the National Institute of Statistics Giorgio Alleva, 2017]. Database: ISTAT [Internet]. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files//2017/09/Audizione-femminicidio-11-gennaio-2018.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Taylor, E.; Banyard, V.; Grych, J.; Hamby, S. Not all behind closed doors: Examining bystander involvement in intimate partner violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2019, 34, 3915–3935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Moreno, C.; Zimmerman, C.; Morris-Gehring, A.; Heise, L.; Amin, A. Addressing violence against women: A call to action. Lancet 2015, 385, 1685–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysova, A. Victims but also perpetrators: Women’s experiences of partner violence. In Women and Children as Victims and Offenders: Background, Prevention, Reitegration; Kury, H., Redo, S., Shea, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 505–537. [Google Scholar]

- Turchik, J.A.; Hebenstreit, C.L.; Judson, S.S. An examination of the gender inclusiveness of current theories of sexual violence in adulthood: Recognizing male victims, female perpetrators, and same-sex violence. Trauma Violence Abuse 2016, 17, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, S. Who are the victims and who are the perpetrators in dating violence? Sharing the role of victim and perpetrator. Trauma Violence Abuse 2017, 20, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.; Wilke, J. Gender Differences in the nature of the Intimate Partner Violence and Effects of perpetrator arrest on revictimization. J. Fam. Violence 2010, 25, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjaden, P.; Thoennes, N. Prevalence and Consequences of Male-to-female and Female-to-male Intimate Partner Violence as Measured by the National Violence Against Women Survey. Violence Against Women 2000, 6, 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margherita, G.; Troisi, G.; Incitti, M.I. “Dreaming Undreamt Dreams” in Psychological Counseling with Italian Women Who Experienced Intimate Partner Violence: A Phenomenological- Interpretative Analysis of the Psychologists’ Experience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtzworth-Munroe, A.; Smutzler, N.; Sandin, E. A brief review of the research on husband violence. Part II: The psychological effects of husband violence on battered women and their children. Aggress Violent Behav. 1997, 2, 179–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiding, M.J.; Smith, S.G.; Basile, K.C.; Walters, M.L.; Chen, J.; Merrick, M.T. Prevalence and Characteristics of Sexual Violence, Stalking and Intimate Partner Violence Victimization. National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, United States, 2011. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, e11–e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasanelli, R.; Galli, I.; Grassia, M.G.; Marino, M.; Cataldo, R.; Lauro, N.C.; Castiello, C.; Grassia, F.; Arcidiacono, C.; Procentese, F. The Use of Partial Least Squares–Path Modelling to Understand the Impact of Ambivalent Sexism on Violence-Justification among Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiurazzi, A.; Arcidiacono, C. Working with domestic violence perpetrators as seen in the representations and emotions of female psychologists and social workers. La Camera Blu. Rivista di Studi di Genere 2017, 16, 47–74. [Google Scholar]

- Misso, D.; Schweitzer, R.D.; Dimaggio, G. Metacognition: A potential mechanism of change in the psychotherapy of perpetrators of domestic violence. J. Psychother. Integr. 2018, 29, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellsberg, M.; Emmelin, M. Intimate Partner Violence and Mental Health. Glob. Health Action 2014, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirigoyen, M.F. Abus de Faiblesse et Autres Manipulations; JC Lattès: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Romito, P. Un Silenzio Assordante. La Violenza Occultata su Donne e Minori [A Deafening Silence. Concealed Violence against Women and Minors]; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rollero, C. The Social Dimensions of Intimate Partner Violence: A Qualitative Study with Male Perpetrators. Sex. Cult. 2019, 24, 749–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcidiacono, C.; Di Napoli, I. Sono Caduta per Le Scale, 1st ed.; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Violence against Women. Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence against Women. 2014. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs239/en/ (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Herrenkohl, T.I.; Mersky, J.P.; Topizes, J. Applied and translational research on trauma responsive programs and policy: Introduction to a special issue of the American Journal of Community Psychology. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 64, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramsky, T.; Watts, C.H.; Garcia-Moreno, C.; Devries, K.; Kiss, L.; Ellsberg, M.; Jansen, H.A.; Heise, L. What factors are associated with recent intimate partner violence? Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santambrogio, J.; Colmegna, F.; Trotta, G.; Cavalleri, P.R.; Clerici, M. Intimate partner violence (IPV) and associated factors: An overview of epidemiological and qualitative evidence in literature. Rivista di Psichiatria 2019, 54, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale, S.; Di Napoli, I.; Esposito, C.; Arcidiacono, C.; Procentese, F. Children Witnessing Domestic Violence in the Voice of Health and Social Professionals Dealing with Contrasting Gender Violence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizen, R.; Morris, M. On Aggression and Violence: An Analytic Perspective, 1st ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, J.M. Personality and situational correlates of self-reported reasons for intimate partner violence among women versus men referred to batterers’ intervention. Behav. Sci. Law 2011, 29, 711–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vincenzo, M.; Troisi, G. Jusqu’à ce que la mort nous sépare. Silence et aliénation dans les violences conjugales. Topique 2018, 143, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troisi, G. Measuring Intimate Partner Violence and Traumatic Affect: Development of VITA, an Italian Scale. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.E. Post-traumatic stress disorder in women: Diagnosis and treatment of battered woman syndrome. Psychol. Psychother. 1991, 28, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.E. Battered Women Syndrome and Self-Defense. Notre Dame J. Law Ethics Public Policy 1992, 6, 321–334. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, K.; Bowen, E.; Brown, S. Desistance from intimate partner violence: A critical review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2013, 18, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, T.P.; Weiss, N.H.; Price, C.; Pugh, N.; Hansen, N.B. Strategies for coping with individual PTSD symptoms: Experiences of African American victims of intimate partner violence. Psychol. Trauma 2018, 10, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, G.L.; Stacks, A.M. Developmental effects of exposure to intimate partner violence in early childhood: A review of the literature. Child. Youth Serv Rev. 2009, 31, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaney, J. Research Review: The Impact of Domestic Violence on Children. Ir. Probat. J. 2015, 12, 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, L.E. The Battered Woman; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, L.E. Survivor Therapy Empowerment Program (STEP). American Psychological Association (APA) Annual Convention. 2009. Available online: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/cps_facpresentations/387 (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Mizen, R. A tale told by an idiot; the “banality” of violence? [Un racconto narrato da un idiota; la “banalità” della violenza?]. La Camera Blu. Rivista di Studi di Genere 2017, 16, 75–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hilder, S.; Freeman, C. Working with Perpetrators of Domestic Violence and Abuse: The Potential for Change. In Domestic Violence, 1st ed.; Hilder, S., Bettinson, V., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016; pp. 237–296. [Google Scholar]

- Galli, I.; Liguori, A.; Lorenzi-Cioldi, F.; Fasanelli, R. Men, Women, and Economic Changes: Social Representations of the Economic Crisis. Interdisciplinaria 2019, 36, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faramarzi, M.; Esmailzadeh, S.; Mosavi, S. A comparison of abused and non-abused women’s definitions of domestic violence and attitudes to acceptance of male dominance. Eur; J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2005, 122, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.J.; An, S. Interventions to improve responses of helping professionals to intimate partner violence: A quick scoping review. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2016, 26, 101–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golding, J.M. Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: A meta-analysis. J. Fam. Violence 1999, 14, 99–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, A.L.; Smith, P.H.; Bethea, L.; King, M.R.; McKeown, R.E. Physical health consequences of physical and psychological intimate partner violence. Arch. Fam. Med. 2000, 9, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, A.L.; Davis, K.E.; Arias, I.; Desai, S.; Sanderson, M.; Brandt, H.M.; Smith, P.H. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2002, 23, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.C. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet 2002, 359, 1331–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, M.C. Intimate partner violence and adverse health consequences: Implications for clinicians. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2011, 5, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saletti-Cuesta, L.; Aizenberg, L.; Ricci-Cabello, I. Opinions and experiences of primary healthcare providers regarding violence against women: A systematic review of qualitative studies. J. Fam. Violence 2018, 33, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, E.M.; Ford, N.J.; Ferrante, D.; Garbelini, F.; Almeida, A.M.D.; Daltoso, D.; Santos, M.A.D. The response to gender violence among Brazilian health care professionals. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2013, 18, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Djikanovic, B.; Celik, H.; Simic, S.; Matejic, B.; Cucic, V. Health professionals’ perceptions of intimate partner violence against women in Serbia: Opportunities and barriers for response improvement. Patient Educ. Couns. 2010, 80, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppäkoski, T.; Paavilainen, E. Interventions for women exposed to acute intimate partner violence: Emergency professionals’ perspective. J. Clin. Nurs. 2013, 22, 2273–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Autiero, M.; Procentese, F.; Carnevale, S.; Arcidiacono, C.; Di Napoli, I. Combatting Intimate Partner Violence: Representations of Social and Healthcare Personnel Working with Gender-Based Violence Interventions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procentese, F.; Fasanelli, R.; Carnevale, S.; Esposito, C.; Pisapia, N.; Arcidiacono, C.; Di Napoli, I. Downside: The perpetrator of Violence in the Representations of Social and Health Professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boira, S.; Carbajosa, P.; Marcuello, C. La violencia en la pareja desde tres perspectivas: Víctimas, agresores y profesionales. Interv. Psicosoc. 2013, 22, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilley-Walker, S.J.; Hester, M.; Turner, W. Evaluation of European Domestic Violence Perpetrator Programmes: Toward a Model for Designing and Reporting Evaluations Related to Perpetrator Treatment Interventions. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2018, 62, 868–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, A. Grounded Theory and Grounded Theorizing; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, J.M. The significance of saturation. Qual. Health Res. 1995, 5, 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legewie, H. Teoria e validità dell’intervista. Riv. di Psicol. di Comunità 2006, 1, 79–95. [Google Scholar]

- Schütze, F. Autobiographical Accounts of War Experiences. An Outline for the Analysis of Topically Focused Autobiographical Texts—Using the Example of the “Robert Rasmus” Account in Studs Terkel’s Book, “The Good War”. Qual. Sociol. Rev. 2014, 10, 224–283. [Google Scholar]

- Arcidiacono, C.; Di Napoli, I.; Carnevale, S. Focalized interview and psychological qualitative research. 2020. Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbar, O.; Dekel, R.; Hyland, P.; Cloitre, M. The role of complex posttraumatic stress symptoms in the association between exposure to traumatic events and severity of intimate partner violence. Child. Abuse Negl. 2019, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pill, N.; Day, A.; Mildred, H. Trauma responses to intimate partner violence: A review of current knowledge. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2017, 34, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reale, E.; Aitoro, R.; Amore, C.; Balsamo, G.; Caso, V.; Cuccurese, C.; Forte, G.; Gargiulo, A.; Lualdi, F.; Piemontese, S.; et al. The “Pink Pathway” center to support women victims of violence (domestic, gender violence and stalking) at the Emergency Unit of San Paolo Hospital in Naples. La Camera Blu. Rivista di Studi di Genere 2017, 16, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Procentese, F.; Di Napoli, I.; Arcidiacono, C.; Cerqua, M. Lavorare in centri per uomini violenti affrontandone l’invisibilità della violenza [Working in centers for violent men facing the invisibility of violence]. Psicologia della Salute 2019, 3, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcidiacono, C.; Bozzaotra, A.; Bravo, G.F.; Reale, E.; Ricciardelli, E. Protocollo Napoli. Available online: https://www.psicamp.it/public/opere/7294-protocollo%20napoli.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Margherita, G.; Troisi, G. Gender violence and shame. The visible and the invisible, from the clinical to the social systems. La camera blu. Rivista di Studi di Genere 2014, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Nunziante Cesàro, A. (Ed.) Chiaroscuri Dell’identità. Sessuazione, sesso e genere. Una Lettura Psicoanalitica [Chiaroscuri of Identity. Sexuality, Sex and Gender. A Psychoanalytic Reading], 1st ed.; Franco Angeli: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brem, M.J.; Florimbio, A.R.; Elmquist, J.; Shorey. R.C. Antisocial Traits, Distress Tolerance, and Alcohol Problems as Predictors of Intimate Partner Violence in Men Arrested for Domestic Violence. Psychol. Violence 2017, 8, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISTAT. Stereotypes about Gender Roles and The Social Image of the Sexual Violence. 2018. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files//2019/12/Report-Gender-Stereotypes-Sexual-Violence_2018_EN.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Esposito, C.; Di Napoli, I.; Esposito, I.; Carnevale, S.; Arcidiacono, C. Violence against Women: A Not in My Backyard (NIMBY) Phenomenon. Violence Gend. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Il Dominio Maschile, 1st ed.; Feltrinelli Editore: Milan, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ruddle, A.; Pina, A.; Vasquez, E. Domestic violence offending behaviors: A review of the literature examining childhood exposure, implicit theories, trait aggression and anger rumination as predictive factors. Aggress Violent Behav. 2017, 34, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizen, R. The affective basis of violence. Infant Ment. Health J. 2019, 40, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldri, A.C.; Ferraro, E. Uomini che Uccidono. Cause, Storie e Investigazioni [Men Who Kill. Causes, Stories and Investigations], 1st ed.; EENET: Milan, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pollak, R.A. An intergenerational model of domestic violence. J. Popul. Econ. 2004, 17, 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcidiacono, C. The community psychologist as a reflective plumber. Glob. J. Community Psychol. Pract. 2017, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suffla, S.; Seedat, M.; Bawa, U. Reflexivity as enactment of critical community psychologies: Dilemmas of voice and positionality in a multi- country photovoice study. J. Community Psychol. 2015, 43, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonn, C.; Arcidiacono, C.; Dutta, U.; Kiguwa, P.; Kloos, B.; Maldonado Torres, N. Beyond Disciplinary Boundaries: Speaking Back to Critical Knowledges, Liberation, and Community. S Afr. J. Psychol. (Spec. Issue) 2017, 47, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, M.H.; Kagan, C. Theory and practice for a critical community psychology in the UK. Psicología Conocimiento y Sociedad 2015, 5, 182–205. [Google Scholar]

- Fasanelli, R.; D’Alterio, V.; De Angelis, L.; Piscitelli, A.; Aria, M. Humanisation of care pathways: Training program evaluation among healthcare professionals. Electron. J. Appl. Stat. Anal. 2017, 10, 485–498. [Google Scholar]

- Heise, L.L. Violence against women: An integrated, ecological framework. Violence Women 1998, 4, 262–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Napoli, I.; Procentese, F.; Carnevale, S.; Esposito, C.; Arcidiacono, C. Ending intimate partner violence (IPV) and locating men at stake. An ecological approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procentese, F.; Di Napoli, I.; Tuccillo, F.; Chiurazzi, A.; Arcidiacono, C. Healthcare Professionals’ Perceptions and Concerns towards Domestic Violence during Pregnancy in Southern Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannetti, E.; Tesi, A. Benessere lavorativo in operatori sociali: Le richieste e le risorse lavorative e personali emersa da un’indagine esplorativa [Work well-being in social workers: The demands and work and personal resources that emerged from an exploratory survey]. Psicologia della Salute 2016, 2, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Features | Percentages/Frequencies |

|---|---|

| Gender n % | 45 F 90 |

| 5 M 10 | |

| Professional Role % | 62 Psychologists and Psychotherapists 12 Social Workers 12 Lawyers 14 Others |

| Work Context % | 30 Anti-violence center for women 20 OLV (“Oltre La Violenza” project for men) 14 Center for families 36 Others |

| Years of Service % (range) | 12 (1 ≥ 5) 24 (6 ≥ 10) 12 (11 ≥ 15) 52 (>15) Mean 27.5 |

| Years in Dealing with Violence % (range) | 32 (1 ≥ 5) 32 (6 ≥ 10) 2 (11 ≥ 15) 34 (>15) Mean 18.31 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Di Napoli, I.; Carnevale, S.; Esposito, C.; Block, R.; Arcidiacono, C.; Procentese, F. “Kept in Check”: Representations and Feelings of Social and Health Professionals Facing Intimate Partner Violence (IPV). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7910. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17217910

Di Napoli I, Carnevale S, Esposito C, Block R, Arcidiacono C, Procentese F. “Kept in Check”: Representations and Feelings of Social and Health Professionals Facing Intimate Partner Violence (IPV). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(21):7910. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17217910

Chicago/Turabian StyleDi Napoli, Immacolata, Stefania Carnevale, Ciro Esposito, Roberta Block, Caterina Arcidiacono, and Fortuna Procentese. 2020. "“Kept in Check”: Representations and Feelings of Social and Health Professionals Facing Intimate Partner Violence (IPV)" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 21: 7910. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17217910

APA StyleDi Napoli, I., Carnevale, S., Esposito, C., Block, R., Arcidiacono, C., & Procentese, F. (2020). “Kept in Check”: Representations and Feelings of Social and Health Professionals Facing Intimate Partner Violence (IPV). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 7910. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17217910