Downside: The Perpetrator of Violence in the Representations of Social and Health Professionals

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.1.1. The Roots of Violence Inflicted by Men

1.1.2. Social and Health Personnel Facing Gender Violence Perpetrators

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures and Methods

3. Results

3.1. The Representation of the Perpetrator

- Difficulty Expressing Themselves and Their Emotions

- Compulsive Obsessive Traits

- Manipulative Behavior

- Narcissistic Traits

- Low Level of Self-Esteem

- Violence as Fear of the Other

3.2. The Representation of Gender-Based Violence Acted by Perpetrators

- Disbelief Towards Domestic Violence

- Invisibility

3.3. The “Naturalness” of Gender-Based Violence

- Violence as a Patriarchal Male Chauvinist Expression

- Social Silence

- The Literacy of Violence

- The Normality of “Violent Men”

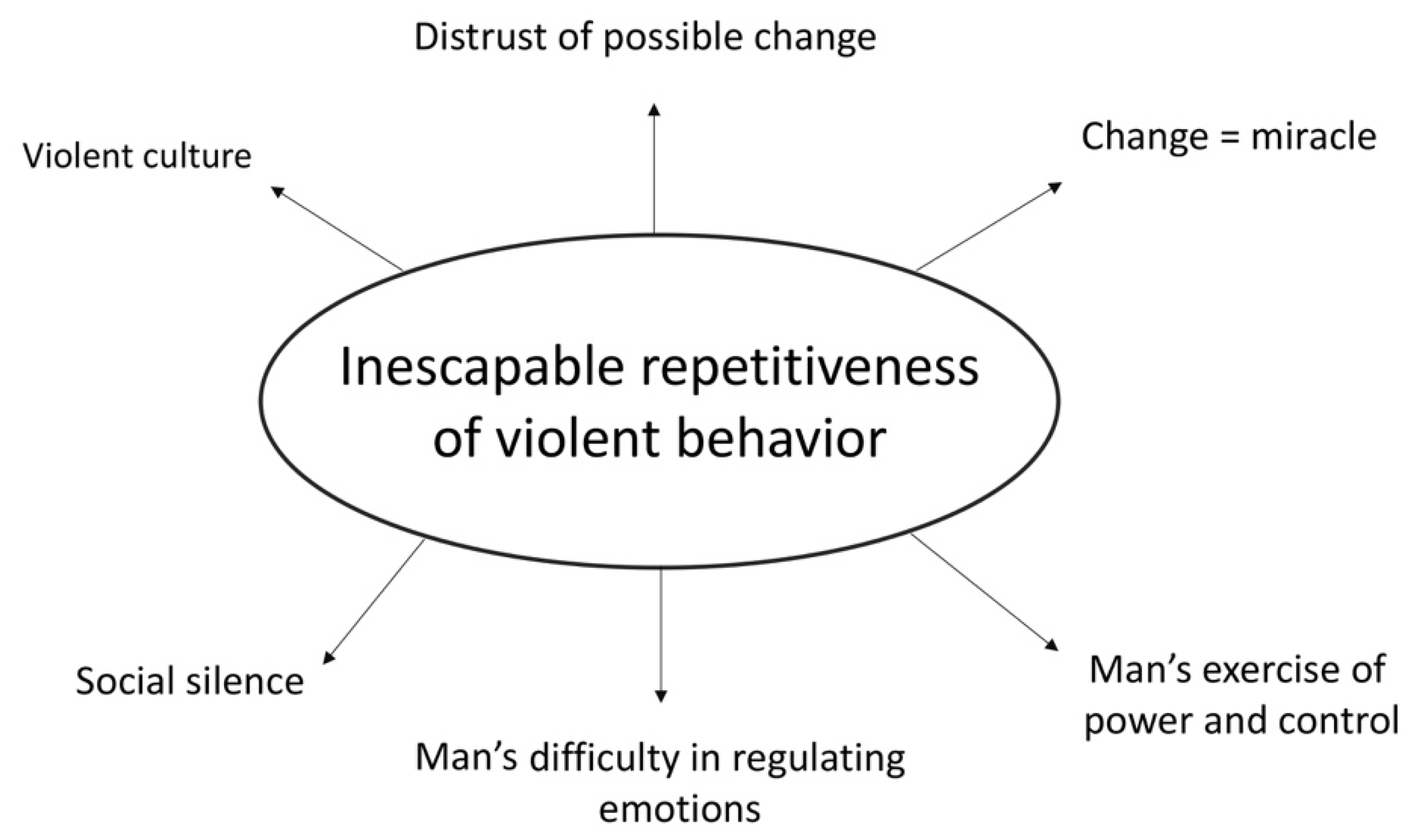

3.4. The Possibility of Change for Gender-Based Violence Perpetrators

- The Perpetrator’s Impossibility to Change

- Fatherhood as an authentic motivation for change

- External and Internal Motivation to Change

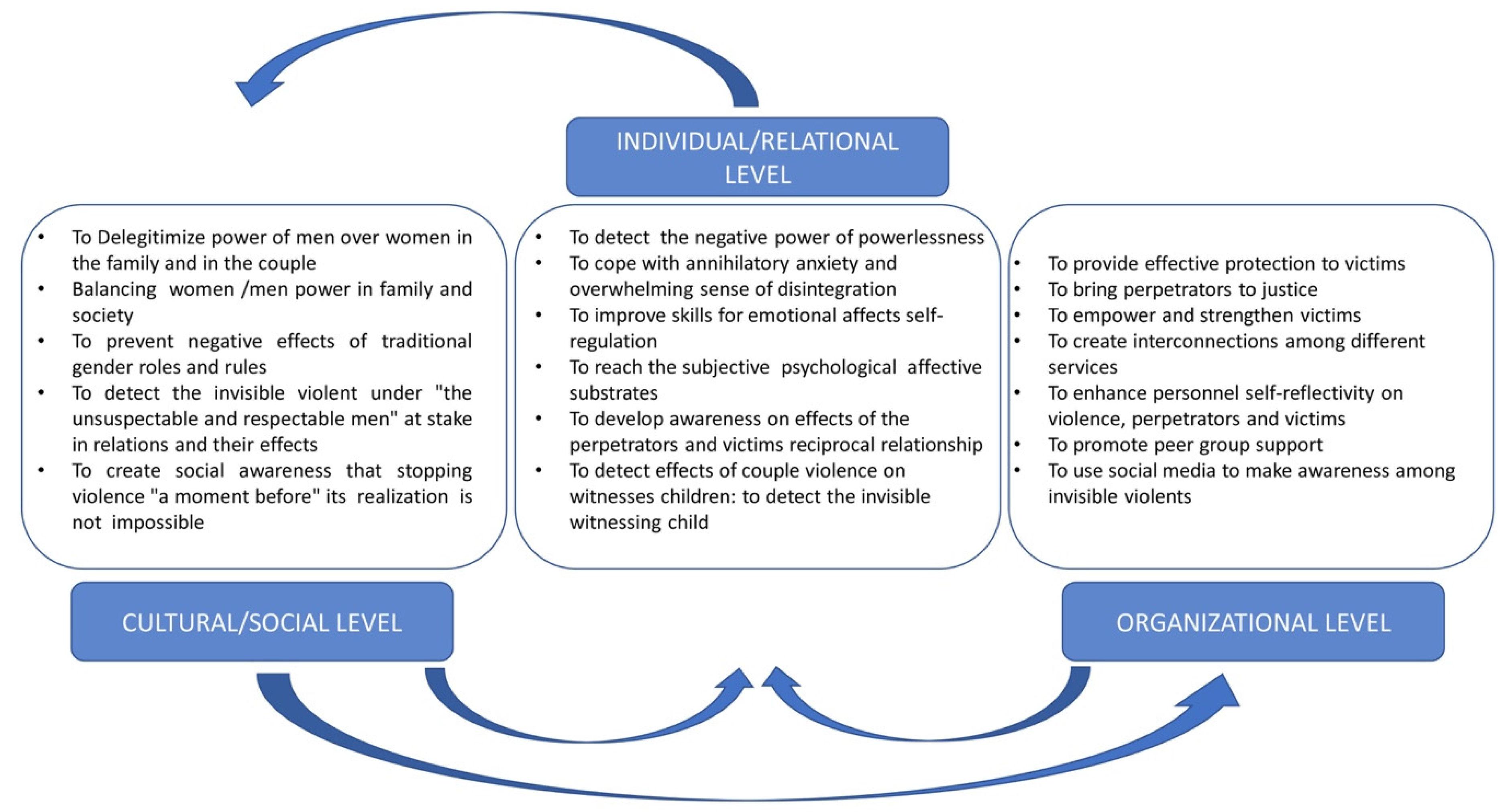

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global and Regional Estimates of Violence against Women. Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-Partner Sexual Violence; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/85239/9789241564625_eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 30 August 2020).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Understanding and Addressing Violence against Women. Intimate Partner Violence; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; Volume 1, Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/77432/WHO_RHR_12.36_eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 30 August 2020).

- Council of Europe. Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/168008482e (accessed on 30 August 2020).

- FRA-European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. Violence against Women: An EU-Wide Survey-Survey Methodology, Sample and Fieldwork; FRA: Vienna, Austria, 2014.

- ISTAT. La Violenza e i Maltrattamenti Contro le Donne Dentro e Fuori la Famiglia; ISTAT: Rome, Italy, 2007; Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files//2011/07/testointegrale.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2019).

- Chiurazzi, A.; Arcidiacono, C.; Helm, S. Treatment Programs for Perpetrators of Domestic Violence: European and International Approaches. New Male Stud. Int. J. 2015, 4, 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lilley-Walker, S.J.; Hester, M.; Turner, W. Evaluation of European Domestic Violence Perpetrator Programmes: Toward a Model for Designing and Reporting Evaluations Related to Perpetrator Treatment Interventions. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2018, 62, 868–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senato della Repubblica. Relazione Sui Dati Riguardanti la Violenza di Genere e Domestica nel Periodo di Applicazione Delle Misure di Contenimento per l’Emergenza da Covid-19. Available online: http://www.senato.it/japp/bgt/showdoc/18/SommComm/0/1157238/index.html?part=doc_dc (accessed on 30 August 2020).

- ISTAT. Stereotypes about Gender Roles and The Social Image of the Sexual Violence. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files//2019/12/Report-Gender-Stereotypes-Sexual-Violence_2018_EN.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2020).

- Di Napoli, I.; Procentese, F.; Carnevale, S.; Esposito, C.; Arcidiacono, C. Ending intimate partner violence (IPV) and locating men at stake. An ecological approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merzagora Betsos, I. Criminologia della Diolenza e dell’Omicidio, dei Reati Sessuali, dei Fenomeni di Dipendenza, 1st ed.; Cedam: Padova, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe, A.; Smutzler, N.; Sandin, E. A brief review of the research on husband violence. Part II: The psychological effects of husband violence on battered women and their children. Aggress. Violent Behav. 1997, 2, 179–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtzworth-Munroe, A.; Smutzler, N.; Bates, L. A brief review of the research on husband violence: Part III: Sociodemographic Factors, Relationship Factors, and Differing Consequences of Husband and Wife Violence. Aggress. Violent Behav. 1997, 2, 285–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollero, C. The Social Dimensions of Intimate Partner Violence: A Qualitative Study with Male Perpetrators. Sex. Cult. 2019, 24, 749–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breindin, M.; Smith, S.G.; Basile, K.C.; Walters, M.; Chen, J.; Merrick, M. Prevalence and Characteristics of Sexual Violence, Stalking, and Intimate Partner Violence Victimization-National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, United States. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. Surveill. Summ. 2014, 63, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- De Vincenzo, M.; Troisi, G. Jusqu’à ce que la mort nous sépare. Silence et al.iénation dans les violences conjugales. Topique 2018, 143, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troisi, G. Measuring intimate partner violence and traumatic affect: Development of VITA, an Italian Scale. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISTAT. Commissione Parlamentare di Inchiesta sul Femminicidio, Nonché su ogni Forma di Violenza di Genere. In Audizione del Presidente dell’Istituto Nazionale di Statistica Giorgio Alleva; ISTAT: Rome, Italy, 2017; Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files//2017/09/Audizione-femminicidio-11-gennaio-2018.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2020).

- Procentese, F.; Di Napoli, I.; Arcidiacono, C.; Cerqua, M. Lavorare in centri per uomini violenti affrontandone l’invisibilità della violenza. Psicol. Della Salut. 2019, 3, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodeo, A.L.; Rubinacci, D.; Scandurra, C. Il ruolo del genere nel lavoro con gli uomini autori di violenza: Affetti e rappresentazioni dei professionisti della salute. La Camera Blu Riv. Studi Genere 2018, 19, 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Misso, D.; Schweitzer, R.D.; Dimaggio, G. Metacognition: A potential mechanism of change in the psychotherapy of perpetrators of domestic violence. J. Psychother. Integr. 2018, 29, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. II Dominio Maschile, 1st ed.; Feltrinelli Editore: Milano, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Di Napoli, I.; Block, R.; Carnevale, S.; Esposito, C.; Arcidiacono, C.; Procentese, F. Kept in check’: Representations and feelings of social and health personnel facing Intimate Partner Violence (IPV). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Galli, I.; Liguori, A.; Lorenzi-Cioldi, F.; Fasanelli, R. Men, Women, and Economic Changes: Social Representations of the Economic Crisis. Interdisciplinaria 2019, 36, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, F.; Clarke, J.; Heim, C.; Harvey, P.D.; Majer, M.; Nemero, C.B. The effects of child abuse and neglect on cognitive functioning in adulthood. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2012, 46, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heward-Belle, S. The Diverse fathering practices of men who perpetrate domestic violence. Aust. Soc. Work 2015, 69, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, P.M.; Martin, S.E.; Dennis, T.A. Emotion regulation as a scientific construct: Methodological challenges and directions for child development research. Child. Dev. 2004, 75, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.; Spinazzola, J.; Ford, J.; Lanktree, C.; Blaustein, M.; Cloitre, M.; DeRosa, R.; Hubbard, R.; Kagan, R.; Liautaud, J.; et al. Complex trauma in children and adolescents. Psychiatr. Ann. 2005, 35, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.T.; Cummings, E.M. Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 116, 387–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddle, A.; Pina, A.; Vasquez, E. Domestic violence offending behaviors: A review of the literature examining childhood exposure, implicit theories, trait aggression and anger rumination as predictive factors. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2017, 34, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizen, R. A tale told by an idiot; the “banality” of violence? La Camera Blu Riv. Studi Genere 2017, 16, 75–96. [Google Scholar]

- Mizen, R. The affective basis of violence. Infant Ment. Health J. 2019, 40, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, P.A.; Biddle, P. Implementing a perpetrator-focused partnership approach to tackling domestic abuse: The opportunities and challenges of criminal justice localism. Criminol. Crim. Justice 2017, 18, 468–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckert, A.; Gondolf, E.W. Predictors of Underreporting of Male Violence by Batterer Program Participants and Their Partners. J. Fam. Violence 2000, 15, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Laurentis, M. Il Silenzio Crudele che Uccide le Donne. Available online: http://stampacritica.org/2018/08/16/silenzio-crudele-uccide-le-donne/ (accessed on 30 August 2020).

- Henning, K.; Jones, A.R.; Holdford, R. I didn’t do it, but if I did I had a good reason: Minimization, denial, and attributions of blame among male and female domestic violence offenders. J. Fam. Violence 2005, 20, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, K.; Holdford, R. Minimization, denial, and victim blaming by batterers: How much does the truth matter? Crim. Justice Behav. 2006, 33, 110–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilder, S.; Freeman, C. Working with perpetrators of domestic violence and abuse: The potential for change. In Domestic Violence; Hilder, S., Bettinson, V., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016; pp. 237–296. [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J.; McCullars, A.; Misra, T.A. Motivations for men and women’s intimate partner violence perpetration: A comprehensive review. Partn. Abus. 2012, 3, 429–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.P. Patriarchal Terrorism and Common Couple Violence: Two Forms of Violence against Women. In Close Relationships: Key Readings, 1st ed.; Reis, H.T., Rusbult, C.E., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2004; pp. 471–482. [Google Scholar]

- Hearn, J. Educating Men About Violence Against Women. Women’s Stud. Q. 1999, 27, 140–151. [Google Scholar]

- Heise, L.L. Violence against women: An integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women 1998, 4, 262–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autiero, M.; Procentese, F.; Carnevale, S.; Arcidiacono, C.; Di Napoli, I. Combatting Intimate Partner Violence: Representations of Social and Healthcare Personnel Working with Gender-Based Violence Interventions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akoensi, T.D.; Koehler, J.A.; Lösel, F.; Humphreys, D.K. Domestic Violence Perpetrator Programs in Europe, Part II A Systematic Review of the State of Evidence. Int. J. Offender Comp. Criminol 2013, 57, 1206–1225. [Google Scholar]

- Arcidiacono, C.; Di Napoli, I. Sono caduta dalle scale. In I Luoghi e Gli Attori della Violenza di Genere, 1st ed.; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Creazzo, G. L’invisibilità degli uomini che usano violenza nelle relazioni di intimità. La ricerca azione in tre città europee. In Uomini che Maltrattano le Donne che Fare? Sviluppare Strategie di Intervento con Uomini che Usano Violenza nelle Relazioni d’Intimità, 1st ed.; Creazzo, G., Bianchi, L., Eds.; Carocci Faber: Roma, Italy, 2009; pp. 73–129. [Google Scholar]

- Arcidiacono, C. The community psychologist as reflective plumber. Glob. J. Community Psychol. Pract. 2017, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sonn, C.; Arcidiacono, C.; Dutta, U.; Kiguwa, P.; Kloos, B.; Maldonado Torres, N. Beyond Disciplinary Boundaries: Speaking Back to Critical Knowledges, Liberation, and Community. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2017, 47, 448–458. [Google Scholar]

- Suffla, S.; Seedat, M.; Bawa, U. Reflexivity as enactment of critical community psychologies: Dilemmas of voice and positionality in a multi-country photovoice study. J. Community Psychol. 2015, 43, 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, F. Practicing Ethnography in Migration-Related Detention Centers: A Reflexive Account. J. Prev. Interv. Community 2017, 45, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasanelli, R.; D’Alterio, V.; De Angelis, L.; Piscitelli, A.; Aria, M. Humanisation of care pathways: Training program evaluation among healthcare professionals. Electron. J. Appl. Stat. Anal. 2017, 10, 484–497. [Google Scholar]

- Chiurazzi, A.; Arcidiacono, C. Working with domestic violence perpetrators as seen in the representations and emotions of female psychologists and social workers. Camera Blu Riv. Stud. Genere. 2017, 16, 47–74. [Google Scholar]

- Swan, S.; Gambone, L.; Caldwell, J.; Sullivan, T.; Snow, D. A review of research on women’s use of violence with male intimate partners. Violence Vict. 2008, 23, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolognini, S. Quel Narciso Così Violento. Available online: https://www.spiweb.it/stampa/rassegna-stampa-2/rassegna-stampa-italiana/quel-narciso-cosi-violentoil-secolo-xix-27-settembre-2012/ (accessed on 30 August 2020).

- Taylor, A.K.; Gregory, A.; Feder, G.; Williamson, E. We’re all wounded healers: A qualitative study to explore the well-being and needs of helpline workers supporting survivors of domestic violence and abuse. Health Soc. Care Community 2018, 27, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale, S.; Di Napoli, I.; Esposito, C.; Arcidiacono, C.; Procentese, F. Children Witnessing Domestic Violence in the Voice of Health and Social Professionals Dealing with Contrasting Gender Violence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4463. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, A.; Akinsulure-Smith, A.M.; Chu, T. Grounded Theory. In Handbook of Methodological Approaches to Community-Based Research; Jason, L.A., Glenwick, D.S., Eds.; Oxford University Press, US: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Legewie, H. Teoria e validità dell’intervista. Riv. Di Psicol. Di Comunità 2006, 1, 79–95. [Google Scholar]

- Schütze, F. Autobiographical Accounts of War Experiences. An Outline for the Analysis of Topically Focused Autobiographical Texts–Using the Example of the “Robert Rasmus” Account in Studs Terkel’s Book, “The Good War”. Qual. Sociol. Rev. 2014, 10, 224–283. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research; SAGE Publication: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis, 1st ed.; SAGE Publication: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, A.E. Situation analyses. Grounded theory mapping after the postmodern turn. Symb. Interact. 2003, 26, 553–576. [Google Scholar]

- Fasanelli, R.; Galli, I.; Grassia, M.G.; Marino, M.; Cataldo, R.; Lauro, N.C.; Castiello, C.; Grassia, F.; Arcidiacono, C.; Procentese, F. The Use of Partial Least Squares–Path Modelling to Understand the Impact of Ambivalent Sexism on Violence-Justification among Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4991. [Google Scholar]

- Margherita, G.; Gargiulo, A.; Troisi, G.; Tessitore, F.; Kapusta, N.D. Italian validation of the capacity to love inventory: Preliminary results. Front. Psycho.l 2018, 9, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaney, J. Research Review: The Impact of Domestic Violence on Children. Ir. Probat. J. 2015, 12, 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Hellmuth, J.C.; Gordon, K.C.; Stuart, G.L.; Moore, T.M. Risk factors for intimate partner violence during pregnancy and postpartum. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2013, 16, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procentese, F.; Di Napoli, I.; Tuccillo, F.; Chiurazzi, A.; Arcidiacono, C. Healthcare Professionals’ Perceptions and Concerns towards Domestic Violence during Pregnancy in Southern Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañón Rodríguez, M.F.; Marín, D.; Fasanelli, R. Pensando en la salud de niños y niñas, el aporte desde las representaciones sociales. Rev. Infanc. Imágenes 2018, 17, 197–208. [Google Scholar]

- Grifoni, G. Non esiste una giustificazione. In L’Uomo che Agisce Violenza Domestica Verso il Cambiamento; Romano Editore: Firenze, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Smith Stover, C. Fathers for Change: A New Approach to Working with Fathers Who Perpetrate Intimate Partner Violence. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 2013, 41, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, N.; Graham-Kevan, N.; Borthwick, R. Fathers and Domestic Violence–building motivation for change through perpetrator programmes. Child. Abus. Rev. 2012, 21, 264–274. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, S. Acting in the children’s best interest? Examining victims’ responses to intimate partner violence. J. Child. Fam Stud. 2011, 20, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, N.; Barnar, M.; Taylor, J. Caring Dads Safer Children: Families’ Perspectives on an Intervention for Maltreating Fathers. Psychol Violence 2017, 7, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strega, S.; Fleet, C.; Brown, L.; Dominelli, L.; Callahan, M.; Walmsley, C. Connecting father absence and mother blame in child welfare policies and practice. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2008, 30, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Perez, V.A.; Ferreiro-Basurto, V.; Navarro-Guzmán, C.; Bosch-Fiol, E. Programas de intervención con maltratadores en España: La perspectiva de los/as profesionales. Interv. Psicosoc. 2016, 25, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boira, S.; Carbajosa, P.; Marcuello, C. La violencia en la pareja desde tres perspectivas: Víctimas, agresores y profesionales. Interv. Psicosoc. 2013, 22, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.D.; Neighbors, C.; Mbilinyi, L.F.; O’Rourke, A.; Zegree, J.; Roffman, R.A.; Edleson, J.L. Evaluating the impact of intimate partner violence on the perpetrator: The perceived consequences of domestic violence questionnaire. J. Interpers. Violence 2010, 25, 1684–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt, C.I.; Murphy, C.M.; Whitaker, D.J.; Sprunger, J.; Dykstra, R.; Woodard, K. The effectiveness of intervention programs for perpetrators and victims of intimate partner violence. Partn. Abus. 2013, 4, 196–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, C.; Di Napoli, I.; Esposito, I.; Carnevale, S.; Arcidiacono, C. Violence against Women: A Not in My Backyard (NIMBY) Phenomenon. Violence Gend. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Codes Interview | Age | Gender | Profession | Work Context | Years of Work | Years of Work with Violence Cases | Work with Perpetrator |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I_01 | 38 | F | Psychologist | Private Practice | From 6 to 10 | From 6 to 10 | Yes |

| I_02 | 34 | F | Psychologist | Antiviolence Center CAV | From 6 to 11 | From 1 to 5 | No |

| I_03 | 37 | F | Psychologist and Psychotherapist | Antiviolence Center CAV | From 6 to 12 | From 1 to 5 | No |

| I_04 | 46 | F | Assistant councilor for equal opportunities | Office of Campania Region | From 1 to 15 | From 1 to 5 | No |

| I_05 | 61 | F | Psychologist and Psychotherapist | Center for Violent Men OLV | Over 15 | Over 15 | Yes |

| I_06 | 55 | F | Emergency Doctor (Campania Region) | Hospital | Over 15 | Over 15 | No |

| I_07 | 53 | F | Social Worker | Center for Families | Over 15 | From 6 to 10 | Yes |

| I_08 | 31 | M | Psychologist and Psychotherapist | Private Practice | From 1 to 5 | From 1 to 5 | No |

| I_09 | 66 | F | Psychologist and Psychotherapist | Center for Violent Men OLV | Over 15 | From 6 to 10 | Yes |

| I_10 | 49 | M | Official in Department of Equal Opportunities | Office of Campania Region | From 11 to 15 | From 6 to 11 | No |

| I_11 | 52 | F | Nurse | Center for Violent Men OLV | Over 15 | From 1 to 5 | No |

| I_12 | 41 | F | Psychologist and Psychotherapist | Antiviolence Center CAV | From 6 to 10 | From 6 to 10 | No |

| I_13 | 46 | F | Equal opportunities office manager | Department of Equal Opportunities | From 11 to 15 | From 11 to 15 | Yes |

| I_14 | 39 | F | Psychologist and Psychotherapist | Antiviolence center CAV | From 11 to 15 | From 6 to 10 | No |

| I_15 | 44 | F | Social worker | Services for Minors and Families | Over 15 | Over 15 | Yes |

| I_16 | 42 | F | Psychologist and Psychotherapist | Antiviolence Center CAV | Over 15 | From 1 to 5 | No |

| I_17 | 43 | F | Lawyer | Antiviolence Center CAV | Over 15 | From 1 to 6 | No |

| I_18 | 30 | F | Psychologist | AntiviolenceCenter CAV | From 6 to 10 | From 6 to 10 | No |

| I_19 | 42 | F | Lawyer | Forensic Association and Antiviolence Center | From 11 to 15 | From 6 to 10 | Yes |

| I_20 | 43 | F | Lawyer | Antiviolence center CAV | From 11 to 15 | From 1 to 5 | No |

| I_21 | 60 | F | Sociologist | Antiviolence center CAV | Over 15 | Over 15 | No |

| I_22 | 70 | F | Psychologist and Psychotherapist | Private Practice | Over 15 | Over 15 | Yes |

| I_23 | 59 | F | Psychologist | Center for Families | Over 15 | Over 15 | Yes |

| I_24 | 35 | F | Psychologist and Psychotherapist | Antiviolence Center CAV | From 6 to 10 | From 6 to 10 | No |

| I_25 | 31 | F | Psychologist and Psychotherapist | Center for violent men OLV | From 6 to 10 | From 6 to 11 | Yes |

| I_26 | 32 | F | Psychologist and Psychotherapist | Center for Violent men OLV | From 1 to 5 | From 1 to 5 | No |

| I_27 | 58 | F | Social worker | Health Consultancy | Over 15 | Over 15 | Yes |

| I_28 | 37 | F | Lawyer | Antiviolence Center CAV | From 6 to 10 | From 6 to 10 | No |

| I_29 | 70 | M | Psychologist and Psychotherapist | Court of Italy | Over 15 | Over 15 | Yes |

| I_30 | 62 | F | Social worker | Center for Families | Over 15 | Over 15 | Yes |

| I_31 | 57 | F | Psychologist | Center for Families | Over 15 | Over 15 | Yes |

| I_32 | 62 | F | Psychologist and Psychotherapist | Center for Violent Men OLV | Over 15 | Over 15 | Yes |

| I_33 | 65 | F | Psychologist and Psychotherapist | Local Health Service (ASL) | Over 15 | Over 15 | Yes |

| I_34 | 41 | F | Councilor for Equal Opportunities | Office of Campania Region | Over 15 | From 1 to 5 | No |

| I_35 | 29 | F | Psychologist | Center for Violent Men OLV | From 1 to 5 | From 1 to 6 | Yes |

| I_36 | 55 | F | Psychologist | Center for Violent Men OLV | Over 15 | From 6 to 10 | Yes |

| I_37 | 41 | F | Psychologist and Psychotherapist | Private Practice | From 6 to 10 | From 1 to 5 | Yes |

| I_38 | 46 | F | Lawyer | Court of Naples | From 6 to 11 | From 6 to 10 | No |

| I_39 | 56 | F | Psychologist and Psychotherapist | Center for Violent Men OLV | Over 15 | From 6 to 10 | Yes |

| I_40 | 27 | F | Social worker | Antiviolence Center CAV | From 1 to 5 | From 1 to 5 | Yes |

| I_41 | 43 | F | Lawyer | Court of Naples | Over 15 | Over 15 | Yes |

| I_42 | 28 | F | Psychologist | Antiviolence Center CAV | From 1 to 5 | From 1 to 5 | No |

| I_43 | 38 | F | Psychologist | Social Promotion Association | From 6 to 10 | From 6 to 10 | No |

| I_44 | 31 | F | Psychologist | Antiviolence Center CAV | From 1 to 5 | From 1 to 5 | No |

| I_45 | 35 | F | Psychologist | 6 Private Practice | From 1 to 5 | From 1 to 5 | No |

| I_46 | 31 | F | Psychologist and Psychotherapist | Center for Violent Men OLV | From 6 to 10 | From 6 to 10 | No |

| I_47 | 61 | F | Psychologist and Psychotherapist | Health Consultancy | Over 15 | From 6 to 10 | No |

| I_48 | 35 | F | Psychologist and Psychotherapist | Antiviolence Center CAV | From 6 to 10 | From 1 to 5 | Yes |

| I_49 | 58 | M | Psychologist | Center for Families | Over 15 | Over 15 | Yes |

| I_50 | 33 | F | Social Worker | Center for Families | From 1 to 5 | From 1 to 5 | No |

| Codes | Categories | Macro-Categories |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Difficulty Thinking about Emotions | - Difficulty Expressing Themselves and Their Emotions | The Representation of the Perpetrator |

| 2. Man Cannot Manage Emotions | ||

| 3. Man’s Impulsiveness | ||

| 4. Man Cannot Manage Conflictual | ||

| Relationships | ||

| 5. Man who Betrays | ||

| 6. Man’s Vulnerability | ||

| 7. Drug Addiction | ||

| 8. Communication Problem | ||

| 9. Repetitiveness of Man’s Violent Behavior | ||

| 10. Lack of Empathy as a Defense Mechanism | ||

| 11. Methods of Releasing Tensions | ||

| 12.Violence as a Way of Releasing Tensions | ||

| 13. Man’s Obsessive Personality | ||

| 14. Perversion of Man | - Compulsive Obsessive Traits | |

| 15. Man’s Paranoia | ||

| 16. Sociopathy | ||

| 17. Man’s Compulsion to Repeat | ||

| 18. Compulsion of Man | ||

| 9. Repetitiveness of Man’s Violent Behavior | ||

| 19. Woman as a Manipulable Object | ||

| 20. Anguish of Abandonment of Man | ||

| 21. Man’s Dependence | - Manipulative Behavior | |

| 22. Constant Search for Confirmation (Man) | ||

| 23. Jealousy of Man | ||

| 24. Manipulative Man | ||

| 25. Abuse of Man | ||

| 26. Exercise of Power | ||

| 27. Men who Show Themselves as Blue Princes | ||

| 28. Denigration of Women | ||

| 29. Isolation of the Woman | ||

| 30. Possession of the Woman by the Man | ||

| 31. Woman Deprived of Liberty | ||

| 32. Feeling of Possession | ||

| 33. Overwhelm | ||

| 34. Man Unable to Manage | ||

| Women’s Emancipation | ||

| 35. Very Controlled Behavior | ||

| 36. Control Through Taxation | ||

| 37. Economic Control | ||

| 38. Control by Man | ||

| 39. Stalking | ||

| 40. Violence as a Woman Correction | ||

| 41. Manipulative Man | ||

| 42. Emotional Violence | ||

| 43. Verbal Violence | ||

| 44. Denigration of Women in the Presence of their Children | ||

| 45. Code of Violence | ||

| 46. Man’s Identity Structured on Woman’s Identity | ||

| 47. Feeling of Possession | ||

| 48. Very Controlling Behavior | ||

| 49. Man’s Narcissism | ||

| 50. Seductive Man | - Narcissistic traits | |

| 51. Man Reluctant to Treatment | ||

| 52. Man’s Lack of Empathy | ||

| 53. Destructive Dynamics | ||

| 54. Projective Identification | ||

| 20. Anguish of Abandonment of Man | ||

| 21. man’s dependence | ||

| 22. constant search for confirmations (man) | ||

| 55. discomfort | ||

| 56. Low self-esteem | - Low level of self-esteem | |

| 57. Impotence | ||

| 58. insecurity | ||

| 59. dissatisfaction | ||

| 60. weakness | ||

| 61. feeling of emptiness | ||

| 62. loneliness | ||

| 63. fragile man | ||

| 64. man victim of himself | ||

| 65. Shame of man | ||

| 6. man’s vulnerability | ||

| 66. separation difficulties | ||

| 67. fusionality | ||

| 68. Projective identification | ||

| 46. man’s identity structured on woman’s identity | ||

| 20. anguish of abandonment of man | ||

| 21. man addiction | - Violence as fear of the other | |

| 22. constant search for confirmation (man) | ||

| 16. sociopathy | ||

| 66. separation difficulties | ||

| 67. fusionality | ||

| 69. danger of loss | ||

| 70. violence as a family mandate | The Representation of Gender-Based Violence Acted by Perpetrators | |

| 71. non-admission of violence | ||

| 72. justification of violence by man | ||

| 73. unawareness of man | ||

| 74. it is difficult to accept that violence takes place within the home | - Disbelief towards domestic violence | |

| 75. social collusion on the man-woman relationship | ||

| 76. isomorphism between society and violent relationship | ||

| 77. invisibility of the phenomenon | ||

| 78. patriarchy | - Invisibility | |

| 79. woman property of man for culture | ||

| 80. on a social level, the diagnosis removes responsibility for man | ||

| 75. social collusion on the man-woman relationship | ||

| 78. patriarchy | - Violence as a patriarchal male chauvinist expression | The “Naturalness” of Gender-Based Violence |

| 79. woman property of man for culture | ||

| 75. social collusion on the man-woman relationship | ||

| 70. violence as a family mandate | ||

| 45. Code of violence | ||

| 81. responsibility of society | ||

| 82. family of origin that does not support the woman | - Social silence | |

| 83. silence of the family | ||

| 75. social collusion on the man-woman relationship | ||

| 84. woman’s education | ||

| 85. man’s education | - The literacy of violence | |

| 86. gender stereotypes | ||

| 87. intergenerational transmission | ||

| 70. violence as a family mandate | ||

| 82. family of origin that does not support the woman | ||

| 88. insane family of origin | ||

| 89. families of origin that do not teach empathy | ||

| 90. lack of release from family of origin | ||

| 83. silence of the family | ||

| 79. woman property of man for culture | ||

| 75. social collusion on the man-woman relationship | ||

| 91. cultural justification of violence | ||

| 92. “normality” of violence in the patriarchal culture | ||

| 83. silence of the family | - The normality of “violent men” | |

| 93. silence of the society | ||

| 78. patriarchy | ||

| 86. gender stereotypes | ||

| 79. woman property of man for culture | ||

| 91. cultural justification of violence | ||

| 45. code of violence | ||

| 94. man’s lack of empathy towards children | - The perpetrator’s impossibility to change | The Possibility of Change for Gender-Based Violence Perpetrators |

| 95. man unaware of the harm inflicted on his children | ||

| 79. woman property of man for culture | ||

| 80. on a social level, the diagnosis removes responsibility for man | ||

| 85. man’s education | ||

| 91. cultural justification of violence | ||

| 96. men aware of aggression but blame the other | ||

| 97. fatherhood as a motivation for change | - Fatherhood as an authentic motivation for change | |

| 98. fatherhood as a motivation for change | - External and internal motivation to change | |

| 99. fear of man | ||

| 100. loss of parental authority | ||

| 101. destruction of ties | ||

| 102. awareness of man | ||

| 103. intrinsic motivation | ||

| 104. achieve personal well-being | ||

| 105. recognition of pain by man | ||

| 106. feeling not judged can help man to change | ||

| 107. avoid punishment (motivation for man to change) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Procentese, F.; Fasanelli, R.; Carnevale, S.; Esposito, C.; Pisapia, N.; Arcidiacono, C.; Napoli, I.D. Downside: The Perpetrator of Violence in the Representations of Social and Health Professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7061. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197061

Procentese F, Fasanelli R, Carnevale S, Esposito C, Pisapia N, Arcidiacono C, Napoli ID. Downside: The Perpetrator of Violence in the Representations of Social and Health Professionals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(19):7061. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197061

Chicago/Turabian StyleProcentese, Fortuna, Roberto Fasanelli, Stefania Carnevale, Ciro Esposito, Noemi Pisapia, Caterina Arcidiacono, and Immacolata Di Napoli. 2020. "Downside: The Perpetrator of Violence in the Representations of Social and Health Professionals" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 19: 7061. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197061

APA StyleProcentese, F., Fasanelli, R., Carnevale, S., Esposito, C., Pisapia, N., Arcidiacono, C., & Napoli, I. D. (2020). Downside: The Perpetrator of Violence in the Representations of Social and Health Professionals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 7061. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197061