Domain Satisfaction and Overall Life Satisfaction: Testing the Spillover-Crossover Model in Chilean Dual-Earner Couples

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Procedure

2.2. Measures

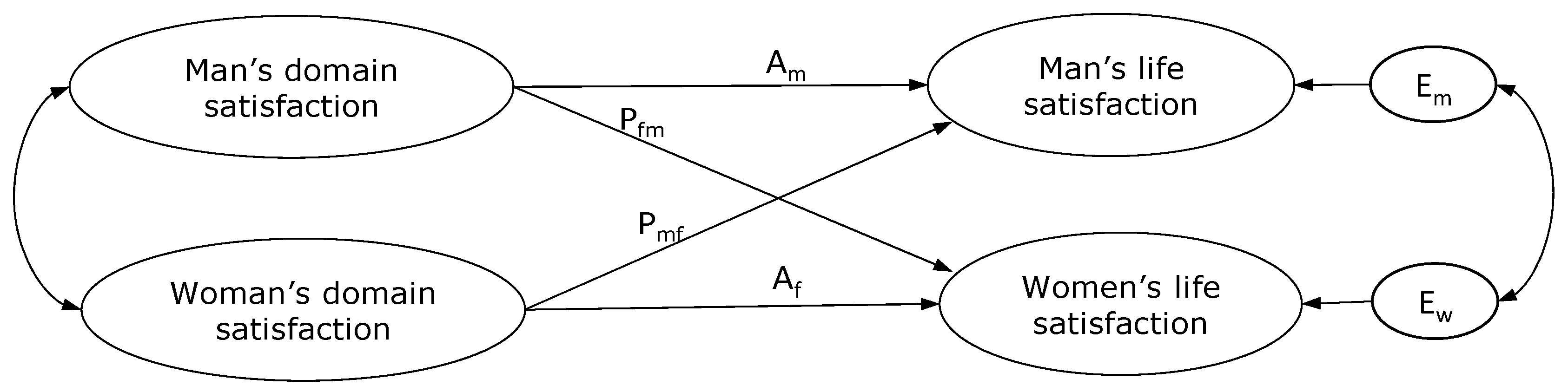

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

3.2. Psychometric Properties of the Scales

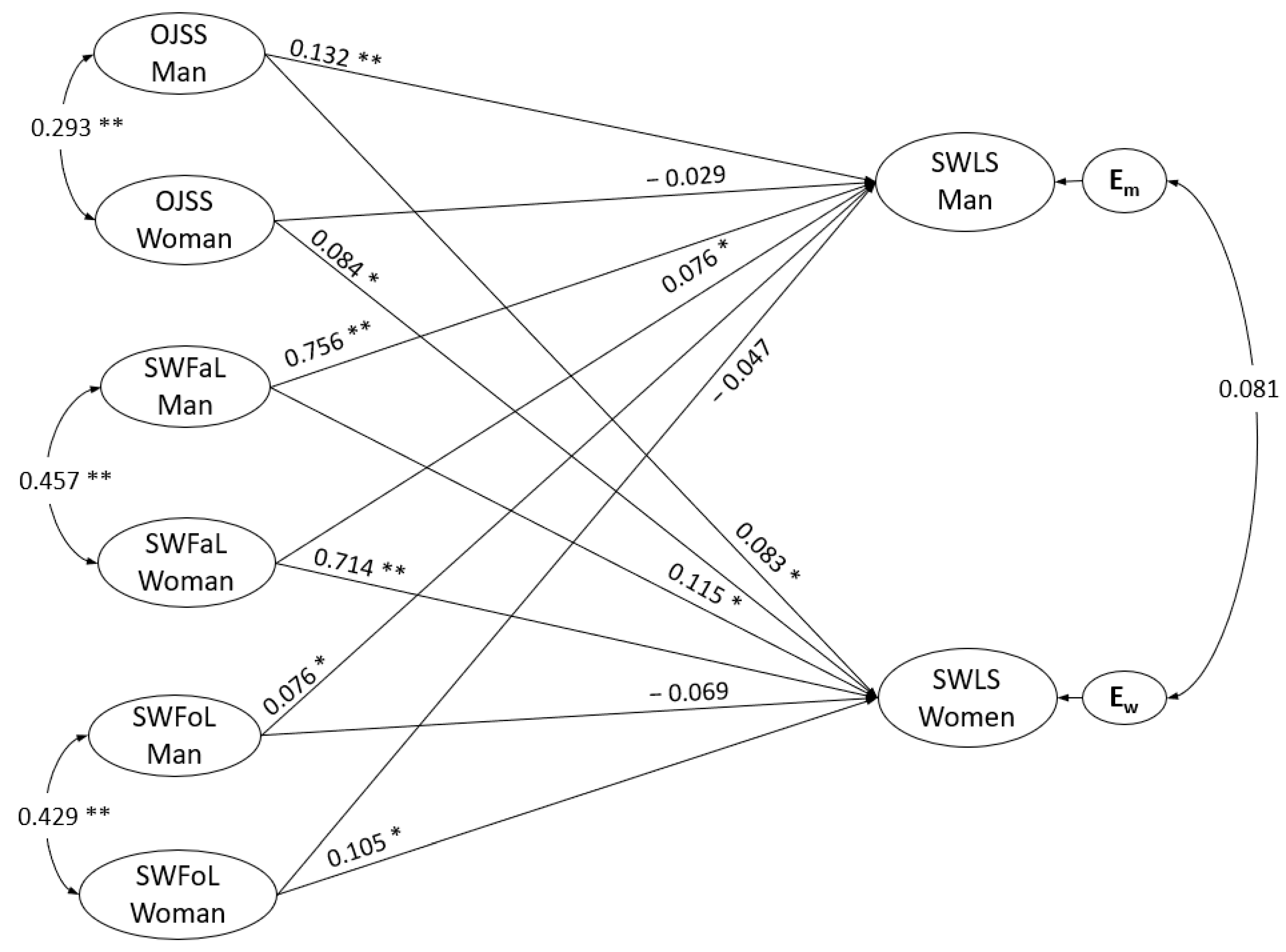

3.3. APIM Results

3.4. Testing Gender Differences

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.; Larsen, R.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brief, A.P.; Butcher, A.H.; George, J.M.; Link, K.E. Integrating bottom-up and top-down theories of subjective well-being: The case of health. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavot, W.; Diener, E. The satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. J. Posit. Psychol. 2008, 3, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busseri, M.A.; Mise, T.R. Bottom-up or top-down? Examining global and domain-specific evaluations of how one’s life is unfolding over time. J. Personal. 2020, 88, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häusler, N.; Hämmig, O.; Bopp, M. Which life domains impact most on self-rated health? A cross-cultural study of Switzerland and its neighbors. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 139, 787–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewe, N.; Bagherzadeh, M.; Araya-Castillo, L.; Thieme, C.; Batista-Foguet, J.M. Life domain satisfactions as predictors of overall life satisfaction among workers: Evidence from Chile. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 118, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bardo, A.R.; Yamashita, T. Validity of domain satisfaction across cohorts in the US. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 117, 367–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viñas-Bardolet, C.; Guillen-Royo, M.; Torrent-Sellens, J. Job characteristics and life satisfaction in the EU: A domains-of-life approach. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2019, 14, 1069–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heller, D.; Watson, D.; Ilies, R. The role of person versus situation in life satisfaction: A critical examination. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 130, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilensky, H.L. Work, careers and social integration. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 1960, 12, 543–560. [Google Scholar]

- Unanue, W.; Gómez, M.E.; Cortez, D.; Oyanedel, J.C.; Mendiburo-Seguel, A. Revisiting the link between job satisfaction and life satisfaction: The role of basic psychological needs. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chmiel, M.; Brunner, M.; Martin, R.; Schalke, D. Revisiting the structure of subjective well-being in middle-aged adults. Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 106, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, T.; Farrell, T.J.; Wethington, E.; Devine, C.M. “Doing our best to keep a routine:” How low-income mothers manage child feeding with unpredictable work and family schedules. Appetite 2018, 120, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnettler, B.; Lobos, G.; Miranda-Zapata, E.; Denegri, M.; Ares, G.; Hueche, C. Diet quality, satisfaction with life, family life and food-related life across families: A cross-sectional pilot study with mother-father-adolescent triads. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schnettler, B.; Miranda-Zapata, E.; Grunert, K.G.; Lobos, G.; Denegri, M.; Hueche, C.; Poblete, H. Life satisfaction of university students in relation to family and food in a developing country. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Song, Y.; Koopmann, J.; Wang, M.; Chang, C.H.D.; Shi, J. Eating your feelings? Testing a model of employees’ work-related stressors, sleep quality, and unhealthy eating. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnan, C.E.; Seidel, A.; MacDermid, S. I just can’t fit it in! Implications of the fit between work and family on health-promoting behaviors. J. Fam. Issues 2017, 38, 1577–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterlin, R.A. Life cycle happiness and its sources: Intersections of psychology, economics, and demography. J. Econ. Psychol. 2006, 27, 463–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rojas, M. The Complexity of Well-Being: A Life-Satisfaction Conception and a Domains-of-Life Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schnettler, B.; Grunert, K.G.; Lobos, G.; Miranda-Zapata, E.; Denegri, M.; Hueche, C. Exploring relationships between family food behaviour and well-being in single-headed and dual-headed households with adolescent children. Curr. Psychol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnettler, B.; Miranda-Zapata, E.; Lobos, G.; Saracostti, M.; Denegri, M.; Lapo, M.; Hueche, C. The mediating role of family and food-related life satisfaction in the relationships between family support, parent work-life balance and adolescent life satisfaction in dual-earner families. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kelley, H.H.; Thibaut, J.W. Interpersonal Relations: A Theory of Interdependence; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, M.E.; Bowen, M. Family Evaluation; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Dobewall, H.; Hintsanen, M.; Savelieva, K.; Hakulinen, C.; Merjonen, P.; Gluschkoff, K.; Keltikangas-Järvinen, L. Intergenerational transmission of latent satisfaction reflected by satisfaction across multiple life domains: A prospective 32-year follow-up study. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 20, 955–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, H.; Cheung, F.M. Testing crossover effects in an actor-partner interdependence model among Chinese dual-earner couples. Int. J. Psychol. 2015, 50, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emanuel, F.; Molino, M.; Lo Presti, A.; Spagnoli, P.; Ghislieri, C. A crossover study from a gender perspective: The relationship between job insecurity, job satisfaction and partners’ family life satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schnettler, B.; Miranda-Zapata, E.; Orellana, L.; Bech-Larsen, T.; Grunert, K.G. The effects of Actor-Partner’s meal production focus on Satisfaction with Food Related Life in cohabiting couples. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 84, 103949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Current Issues in Work and Organizational Psychology. New Frontiers in Work and Family Research; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands–resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, R.S.; Krings, F. How was your day, darling? A literature review of positive and negative crossover at the work-family interface in couples. Eur. Psychol. 2016, 21, 296–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westman, M.; Bakker, A.B. Crossover of Burnout among Health Care Professionals; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Matias, M.; Ferreira, T.; Vieira, J.; Cadima, J.; Leal, T.; Matos, P. Workplace family support, parental satisfaction, and work–family conflict: Individual and crossover effects among dual-earner couples. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 66, 628–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, M.; Gagnon-Girouard, M.P.; Sabourin, S.; Bégin, C. Emotion suppression and food intake in the context of a couple discussion: A dyadic analysis. Appetite 2018, 120, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnettler, B.; Miranda-Zapata, E.; Grunert, K.G.; Lobos, G.; Lapo, M.; Hueche, C. Testing the spillover-crossover model between work-life balance and satisfaction in different domains of life in dual-earner households. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, V.; Joshanloo, M.; Đunda, D.; Bakhshi, A. Gender differences in the relationship between domain-specific and general life satisfaction: A study in Iran and Serbia. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2017, 12, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vleet, M.; Helgeson, V.; Korytkowski, M.; Seltman, H.; Hausmann, L. Communally Coping with Diabetes: An Observational Investigation Using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model. J. Fam. Psychol. 2018, 32, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnettler, B.; Hueche, C.; Andrades, J.; Ares, G.; Miranda, H.; Orellana, L.; Grunert, K. How is satisfaction with food-related life conceptualized? A comparison between parents and their adolescent children in dual-headed households. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 86, 104021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnettler, B.; Miranda-Zapata, E.; Grunert, K.G.; Lobos, G.; Lapo, M.; Hueche, C. Satisfaction with food-related life and life satisfaction: A triadic analysis in dual-earner parents families. Cad. Saúde Pública 2020, 36, e00090619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, A.; Musick, K.; Fischer, J.; Flood, S. Mothers’ and fathers’ well-being in parenting across the arch of child development. J. Marriage Fam. 2018, 80, 992–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, P. Diferencias en la percepción de la satisfacción laboral en una muestra de personal de administración. Bol. Psicol. 2006, 88, 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ariza-Montes, A.; Arjona-Fuentes, J.M.; Han, H.; Law, R. The price of success: A study on chefs’ subjective well-being, job satisfaction, and human values. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 69, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewe, N.; Araya-Castillo, L.; Thieme, C.; Batista-Foguet, J.M. Self-employment as a moderator between work and life satisfaction. Acad. Rev. Latinoam. De Adm. 2015, 28, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edralin, D.M. Work and life harmony: An exploratory case study of EntrePinays. DLSU Bus. Econ. Rev. 2013, 22, 15–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rain, J.S.; Lane, I.M.; Steiner, D.D. A current look at the job satisfaction/life satisfaction relationship: Review and future considerations. Hum. Relat. 1991, 44, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgellis, Y.; Lange, T. Traditional versus secular values and the job–life satisfaction relationship across Europe. Br. J. Manag. 2012, 23, 437–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bowling, N.A.; Eschleman, K.J.; Wang, Q. A meta-analytic examination of the relationship between job satisfaction and subjective well-being. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 915–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Headey, B.; Muffels, R. Towards a theory of medium term Life Satisfaction: Similar results for Australia, Britain and Germany. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 134, 359–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Vergel, A.I.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, A. The spillover and crossover of daily work enjoyment and well-being: A diary study among working couples. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Organ. 2013, 29, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Botha, F.; Booysen, F.; Wouters, E. Satisfaction with family life in South Africa: The role of socioeconomic status. J. Happiness Stud. 2018, 19, 2339–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabriskie, R.B.; Ward, P.J. Satisfaction with family life scale. Marriage Fam. Rev. 2013, 49, 446–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, E.; Willoughby, B.J. Associations between beliefs about marriage and life satisfaction: The moderating role of relationship status and gender. J. Fam. Stud. 2018, 24, 274–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabriskie, R.; McCormick, B. Parent and child perspectives of family leisure involvement and satisfaction with family life. J. Leis. Res. 2003, 35, 163–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, F.; Booysen, F. Family functioning and life satisfaction and happiness in South African Households. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 119, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, L.; Schimmack, U. Examining sources of self-informant agreement in life-satisfaction judgments. J. Res. Personal. 2010, 44, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.M. Effects of Daily Parenting Uplifts on Well-being of Mothers with Young Children in Taiwan. J. Fam. Issues 2020, 41, 542–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnettler, B.; Rojas, J.; Grunert, K.G.; Lobos, G.; Miranda-Zapata, E.; Lapo, M.; Hueche, C. Family and food variables that influence life satisfaction of mother-father-adolescent triads in a South American country. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.L.; Vallen, B. Expanding the Lens of Food Well-Being: An Examination of Contemporary Marketing, Policy, and Practice with an Eye on the Future. J. Public Policy Mark. 2019, 38, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G.; Dean, M.; Raats, M.M.; Nielsen, N.A.; Lumbers, M. A measure of satisfaction with food-related life. Appetite 2007, 49, 486–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Block, L.G.; Grier, S.A.; Childers, T.L.; Davis, B.; Ebert, J.E.; Kumanyika, S.; Pettigrew, S. From nutrients to nurturance: A conceptual introduction to food well-being. J. Public Policy Mark. 2011, 30, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salvy, S.J.; Miles, J.N.; Shih, R.A.; Tucker, J.S.; D’Amico, E.J. Neighborhood, family and peer-level predictors of obesity-related health behaviors among young adolescents. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2017, 42, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speirs, K.E.; Hayes, J.T.; Musaad, S.; VanBrackle, A.; Sigman-Grant, M.; All 4 Kids Obesity Resiliency Research Team. Is family sense of coherence a protective factor against the obesogenic environment? Appetite 2016, 99, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, R.; Grunert, K.G. Satisfaction with food-related life and beliefs about food health, safety, freshness and taste among the elderly in China: A segmentation analysis. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 79, 103775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobos, G.; Schnettler, B.; Arévalo, D.; Padilla, C.; Lapo, M.C.; Bustamante, M. The gender role in the relationship between food-related perceived resources and quality of life among Ecuadorian elderly. Food Sci. 2019, 39, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schnettler, B.; Miranda, H.; Lobos, G.; Orellana, L.; Sepúlveda, J.; Denegri, M.; Grunert, K.G. Eating habits and subjective well-being. A typology of students in Chilean state universities. Appetite 2015, 89, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.; Cho, M.; Kim, Y.; Ahn, J. The Relationships among satisfaction with food-related life, depression, isolation, social support, and overall satisfaction of life in elderly South Koreans. J. Korean Diet. Assoc. 2013, 19, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schnettler, B.; Miranda, H.; Sepúlveda, J.; Denegri, M.; Mora, M.; Lobos, G.; Grunert, K.G. Psychometric properties of the Satisfaction with Food-Related Life Scale: Application in southern Chile. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2013, 45, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnettler, B.; Lobos, G.; Orellana, L.; Grunert, K.G.; Sepúlveda, J.; Mora, M.; Denegri, M.; Miranda, H. Analyzing Food-Related Life Satisfaction and other Predictors of Life Satisfaction in Central Chile. Span. J. Psychol. 2015, 18, E38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Diener, E.; Fujita, F. Resources, personal strivings, and subjective well-being: A nomothetic and idiographic approach. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 68, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M.; Sorensen, S. Influences of socioeconomic status, social network, and competence on subjective well-being in later life: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Aging 2000, 15, 187–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westman, M. Stress and strain crossover. Hum. Relat. 2001, 54, 717–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucel, D.; Fan, W. Work–family conflict and well-being among German couples: A longitudinal and dyadic approach. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2019, 60, 377–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucel, D. The dyadic nature of relationships: Relationship satisfaction among married and cohabiting couples. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2018, 13, 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucel, D.; Latshaw, B.A. Spillover and Crossover Effects of Work-Family Conflict among Married and Cohabiting Couples. Soc. Ment. Health 2020, 10, 35–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, R.C.; Raudenbush, S.W.; Brennan, R.T.; Pleck, J.H.; Marshall, N.L. Change in job and marital experiences and change in psychological distress: A longitudinal study of dual-earner couples. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 839–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnettler, B.; Miranda, H.; Sepúlveda, J.; Denegri, M. Satisfacción con la alimentación y la vida, un estudio exploratorio en estudiantes de la Universidad de La Frontera, Temuco- Chile. Psicol. Soc. 2011, 23, 426–435. [Google Scholar]

- Agho, A.O.; Price, J.L.; Mueller, C.W. Discriminant validity of measures of job satisfaction, positive affectivity and negative affectivity. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1992, 65, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brayfield, A.H.; Rothe, H.F. An index of job satisfaction. J. Appl. Psychol. 1951, 35, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korff, J.; Biemann, T.; Voelpel, S.C. Human resource management systems and work attitudes: The mediating role of future time perspective. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Zvonkovic, A.M.; Crawford, D.W. The impact of work–family conflict and facilitation on women’s perceptions of role balance. J. Fam. Issues 2014, 35, 1252–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnettler, B.; Denegri, M.; Miranda-Zapata, E.; Saracostti, M. Interrelaciones Trabajo-Familia-Alimentación y Satisfacción Vital en Familias Nucleares con dos Ingresos Parentales e Hijos Adolescentes, en Tres Regiones de Chile: Un Estudio Transversal y Longitudinal; Conicyt: Santiago, Chile, 2018.

- Asociación de Investigadores de Mercado (AIM) 2016. Cómo Clasificar los Grupos Socioeconómicos en Chile; Asociación de Investigadores de Mercado (AIM): Chile, 2016. Available online: http://www.iab.cl/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Presentaci%C3%B3n-final-AIM.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2018).

- Claxton, S.E.; DeLuca, H.K.; Van Dulmen, M.H. Testing psychometric properties in dyadic data using confirmatory factor analysis: Current practices and recommendations. Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 22, 181–198. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, R.P. Theoretical foundations of principal factor analysis, canonical factor analysis, and alpha factor analysis. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 1970, 23, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, D.A.; Kashy, D.A.; Cook, W.L. Dyadic Data Analysis; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hau, K.T.; Grayson, D. Goodness of Fit Evaluation in Structural Equation Modeling; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.S.; Shin, Y.J. Social cognitive predictors of Korean secondary school teachers’ job and life satisfaction. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 102, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Nacional de Productividad (CNP). Mujeres en el Mundo Laboral: Un Aporte Para Chile. Más Oportunidades, Crecimiento y Bienestar; Comisión Nacional de Productividad (CNP): Chile, 2017. Available online: http://www.comisiondeproductividad.cl/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Participacion_Laboral_Femenina_26_septiembre.pdf. (accessed on 13 April 2018).

- Beck, K.L.; Jones, B.; Ullah, I.; McNaughton, S.A.; Haslett, S.J.; Stonehouse, W. Associations between dietary patterns, socio-demographic factors and anthropometric measurements in adult New Zealanders: An analysis of data from the 2008/09 New Zealand Adult Nutrition Survey. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 1421–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebestreit, A.; Intemann, T.; Siani, A.; De Henauw, S.; Eiben, G.; Kourides, Y.A.; Kovacs, E.; Moreno, L.A.; Veidebaum, T.; Krogh, V.; et al. Dietary patterns of European children and their parents in association with family food environment: Results from the I. Family Study. Nutrients 2017, 92, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westman, M.; Vinokur, A.D. Unraveling the relationship of distress levels within couples: Common stressors, empathic reactions, or crossover via social interaction? Hum. Relat. 1998, 51, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Negy, C.; Snyder, D.K. Assessing family-of-origin functioning in Mexican American adults: Retrospective application of the Family Environment Scale. Assessment 2006, 13, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mötteli, S.; Siegrist, M.; Keller, C. Women’s social eating environment and its associations with dietary behavior and weight management. Appetite 2017, 110, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharif, M.Z.; Alcalá, H.E.; Albert, S.L.; Fischer, H. Deconstructing family meals: Do family structure, gender and employment status influence the odds of having a family meal? Appetite 2017, 114, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, S.; O’Driscoll, M.P.; Brough, P.; Kalliath, T.; Siu, O.L.; Timms, C.; Lo, D. The relationship of social support with well-being outcomes via work–family conflict: Moderating effects of gender, dependants and nationality. Hum. Relat. 2017, 70, 544–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Peng, Y.; Zhao, P.; Hayes, R.; Jimenez, W.P. Fighting for time: Spillover and crossover effects of long work hours among dual-earner couples. Stress Health 2019, 35, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schösler, H.; de Boer, J.; Boersema, J.J.; Aiking, H. Meat and masculinity among young Chinese, Turkish and Dutch adults in the Netherlands. Appetite 2015, 89, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, L.; Ekström, M.P.; Hach, S.; Bøker Lund, T. Who is Cooking Dinner? Food Cult. Soc. 2015, 18, 589–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE (Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas). Censo de Población y Vivienda 2017; INE: Chile, 2018. Available online: https://redatam-ine.ine.cl/redbin/RpWebEngine.exe/Portal?BASE=CENSO_2017&lang=esp (accessed on 5 August 2019).

- Shockley, K.M.; Douek, J.; Smith, C.R.; Peter, P.Y.; Dumani, S.; French, K.A. Cross-cultural work and family research: A review of the literature. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 101, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headey, B.; Muffels, R.; Wagner, G.G. Parents transmit happiness along with associated values and behaviors to their children: A lifelong happiness dividend? Soc. Ind. Res. 2014, 116, 909–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Characteristic | Total Sample | p-Value 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Age (Mean (SD)) 1 | ||

| Woman | 39.1 (7.2) | 0.000 |

| Man | 42.0 (8.9) | |

| Number of family members (Mean (SD)) | 4.4 (1.0) | |

| Number of children (Mean (SD)) | 2.2 (0.8) | |

| Socioeconomic status (%) | ||

| High | 22.2 | |

| Middle | 61.5 | |

| Low | 16.3 | |

| Gender of the main breadwinner (%) | ||

| Female | 23.3 | |

| Male | 76.7 | |

| Number of days/week couples ate together (Mean (SD)) | ||

| Breakfast | 2.8 (2.3) | |

| Lunch | 3.3 (2.2) | |

| Dinner | 2.5 (3.1) | |

| Satisfaction with life (SWLS) (Mean (SD)) 1 | ||

| Woman | 23.2 (4.8) | 0.003 |

| Man | 24.1 (4.6) | |

| Satisfaction with family life (SWFaL) (Mean (SD)) 1 | ||

| Woman | 23.6 (4.8) | 0.001 |

| Man | 24.7 (4.6) | |

| Satisfaction with food-related life (SWFoL) (Mean (SD)) 1 | ||

| Woman | 21.3 (4.8) | 0.001 |

| Man | 22.5 (4.6) | |

| Job satisfaction (OJSS) (Mean (SD)) 1 | ||

| Woman | 22.3 (4.8) | 0.540 |

| Man | 22.4 (5.0) | |

| Type of employment (%) 2 | 0.460 | |

| Woman employee | 72.7 | |

| Woman self-employed | 27.3 | |

| Man employee | 74.8 | |

| Man self-employed | 25.2 | |

| Working hours (%) 2 | ||

| Woman working 45 h per week | 59.2 | 0.000 |

| Woman working less than 45 h per week | 40.8 | |

| Man working 45 h per week | 72.3 | |

| Man working less than 45 h per week | 27.7 |

| Scale | Loadings Range (min–max) | Omega | AVE | Woman’s OJJS | Man’s OJJS | Woman’s SWFaL | Man’s SWFaL | Woman’s SWFoL | Man’s SWFoL | Woman’s SWLS | Man’s SWLS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Woman’s OJJS | 0.518–0.911 | 0.91 | 0.65 | - | 0.110 | 0.071 | 0.063 | 0.077 | 0.038 | 0.114 | 0.057 |

| Man’s OJJS | 0.571–0.882 | 0.91 | 0.62 | 0.332 ** | - | 0.024 | 0.076 | 0.011 | 0.065 | 0.058 | 0.125 |

| Woman’s SWFaL | 0.771–0.934 | 0.94 | 0.75 | 0.266 ** | 0.155 ** | - | 0.250 | 0.140 | 0.135 | 0.549 | 0.205 |

| Man’s SWFaL | 0.716–0.955 | 0.92 | 0.71 | 0.250 ** | 0.275 ** | 0.500 ** | - | 0.078 | 0.226 | 0.239 | 0.587 |

| Woman’s SWFoL | 0.630–0.890 | 0.89 | 0.62 | 0.278 ** | 0.104 * | 0.374 ** | 0.280 ** | - | 0.225 | 0.151 | 0.064 |

| Man’s SWFoL | 0.652–0.919 | 0.90 | 0.65 | 0.195 ** | 0.255 ** | 0.368 ** | 0.475 ** | 0.474 ** | - | 0.118 | 0.210 |

| Woman’s SWLS | 0.815–0.946 | 0.94 | 0.76 | 0.338 ** | 0.241 ** | 0.741 ** | 0.489 ** | 0.389 ** | 0.343 ** | - | 0.275 |

| Man’s SWLS | 0.749–0.843 | 0.93 | 0.71 | 0.239 ** | 0.354 ** | 0.453 ** | 0.766 ** | 0.253 ** | 0.458 ** | 0.524 ** | - |

| Hypothesis | Spillover | Relation Found | Crossover | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H13 | Men’s job satisfaction to their own life satisfaction | > | Women’s job satisfaction to men’s life satisfaction. | Supported |

| H14 | Women’s job satisfaction to their own life satisfaction | ns | Men’s job satisfaction to women’s life satisfaction. | Not Supported |

| H15 | Men’s satisfaction with family life to their own life satisfaction | > | Women’s satisfaction with family life to men’s life satisfaction. | Not supported |

| H16 | Women’s satisfaction with family life to their own life satisfaction | > | Men’s satisfaction with family life to women’s life satisfaction. | Supported |

| H17 | Men’s satisfaction with food-related life to their own life satisfaction | ns | Women’s satisfaction with food-related life to men’s life satisfaction. | Not supported |

| H18 | Women’s satisfaction with food-related life to their own life satisfaction | > | Men’s satisfaction with food-related life to women’s life satisfaction. | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schnettler, B.; Miranda-Zapata, E.; Orellana, L.; Poblete, H.; Lobos, G.; Lapo, M.; Adasme-Berríos, C. Domain Satisfaction and Overall Life Satisfaction: Testing the Spillover-Crossover Model in Chilean Dual-Earner Couples. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7554. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207554

Schnettler B, Miranda-Zapata E, Orellana L, Poblete H, Lobos G, Lapo M, Adasme-Berríos C. Domain Satisfaction and Overall Life Satisfaction: Testing the Spillover-Crossover Model in Chilean Dual-Earner Couples. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(20):7554. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207554

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchnettler, Berta, Edgardo Miranda-Zapata, Ligia Orellana, Héctor Poblete, Germán Lobos, María Lapo, and Cristian Adasme-Berríos. 2020. "Domain Satisfaction and Overall Life Satisfaction: Testing the Spillover-Crossover Model in Chilean Dual-Earner Couples" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 20: 7554. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207554

APA StyleSchnettler, B., Miranda-Zapata, E., Orellana, L., Poblete, H., Lobos, G., Lapo, M., & Adasme-Berríos, C. (2020). Domain Satisfaction and Overall Life Satisfaction: Testing the Spillover-Crossover Model in Chilean Dual-Earner Couples. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(20), 7554. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207554