Integrating Health and Educational Perspectives to Promote Preschoolers’ Social and Emotional Learning: Development of a Multi-Faceted Program Using an Intervention Mapping Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Research Setting

2.2. Step 1: Logic Model of the Problem

2.2.1. Intervention Design Group

2.2.2. Literature Reviews

2.2.3. Qualitative Interviews and Focus Groups

2.3. Step 2: Identification of Program Outcomes and Objectives

2.4. Step 3: Program Design

2.5. Step 4: Program Production

2.6. Step 5: Program Implementation Plan

2.7. Step 6: Evaluation Plan

3. Results

3.1. Step 1: Logic Model of the Problem

3.1.1. Determinants of Educator Behaviour

3.1.2. Literature Reviews of SEL Programs

3.1.3. Qualitative Interviews and Focus Groups

3.1.4. Feedback from the Advisory Group

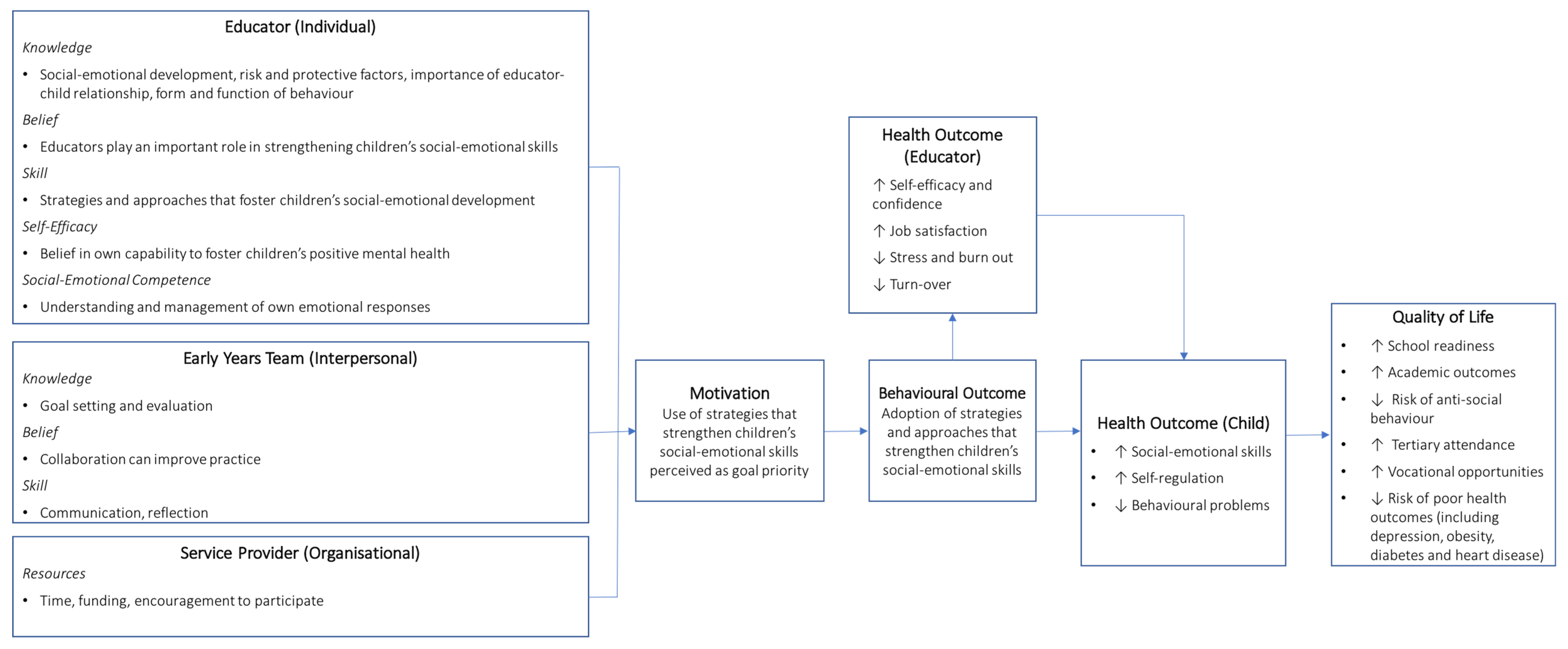

3.1.5. Program Goal and Logic Model

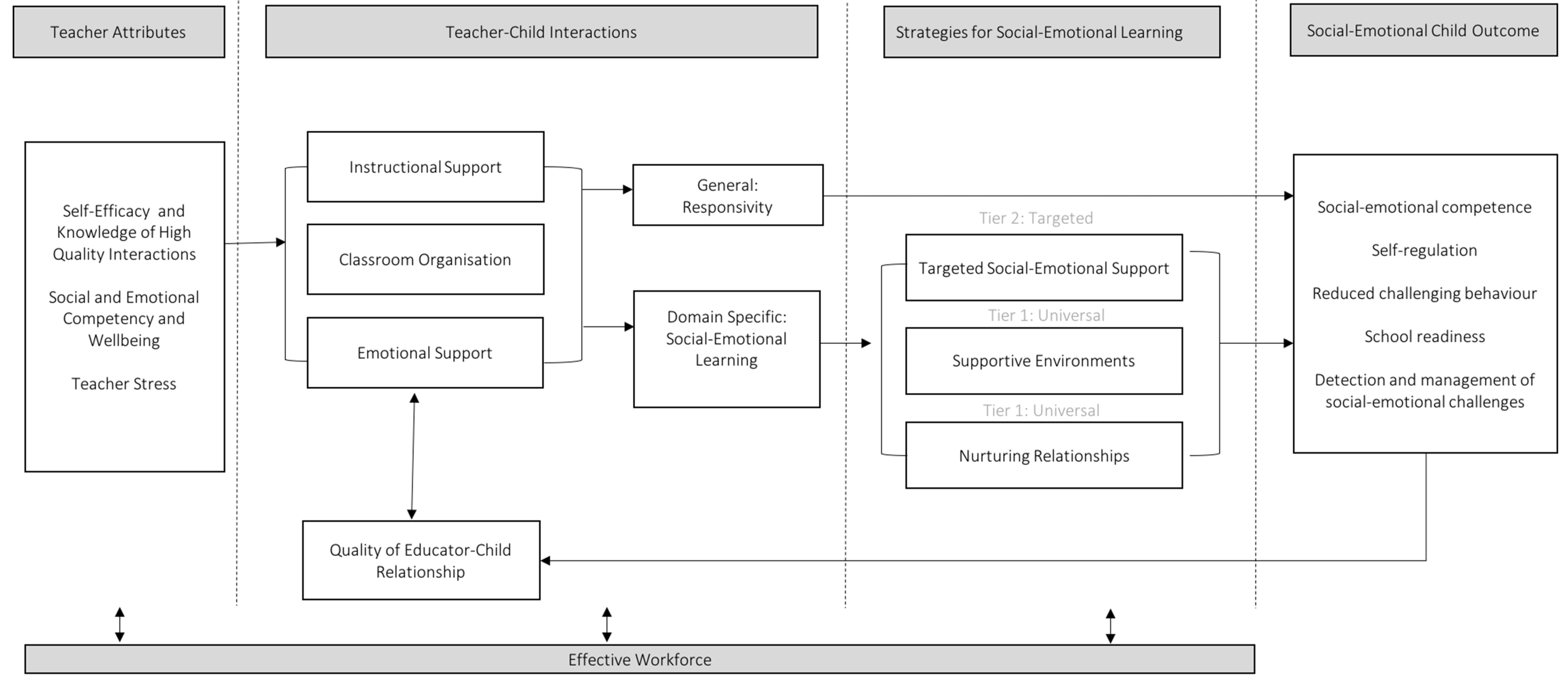

3.1.6. A Framework to Guide Program Design

3.2. Step 2: Program Outcomes and Objectives

3.3. Step 3: Program Design

3.4. Step 4: Program Production

3.5. Step 5: Program Implementation Plan

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shonkoff, J.P.; Phillips, D. From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, L.; Kelly, B. Transforming the Workforce for Children Birth Through Age 8: A Unifying Foundation; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Denham, S.A.; Brown, C. Plays nice with others’: Social-emotional learning and academic success. Early Educ. Dev. 2010, 5, 652–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denham, S.A.; Bassett, H.H.; Zinsser, K.; Wyatt, T.M. How preschoolers’ social—Emotional learning predicts their early school success: Developing theory-promoting, competency-based assessments. Infant Child Dev. 2014, 23, 426–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, M.H.; Hahn, C.S.; Haynes, O.M. Social competence, externalizing, and internalizing behavioral adjustment from early childhood through early adolescence: Developmental cascades. Dev. Psychopathol. 2010, 22, 717–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bor, W.; McGee, T.R.; Fagan, A.A. Early risk factors for adolescent antisocial behaviour: An Australian longitudinal study. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2004, 38, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, S.B. Maladjustment in preschool children: A developmental psychopathology perspective. In Blackwell Handbook of Early Childhood Development; McCartney, K., Phillips, D., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 358–377. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Skills for Social Progress: The Power of Social and Emotional Skills; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D.E.; Greenberg, M.; Crowley, M. Early social-emotional functioning and public health: The relationship between kindergarten social competence and future wellness. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 2283–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briggs-Gowan, M.J.; Carter, A.S.; Skuban, E.M.; Horwitz, S.M. Prevalence of social-emotional and behavioral problems in a community sample of 1- and 2-year-old children. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2001, 40, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huaqing Qi, C.; Kaiser, A.P. Behavior problems of preschool children from low-income families: Review of the literature. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2003, 23, 188–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, J.K.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Lucas, N.; Wake, M.; Scalzo, K.; Nicholson, J.M. Risk factors for childhood mental health symptoms: National longitudinal study of australian children. Pediatrics 2011, 128, e865–e879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauner, C.B.; Stephens, C.B. Estimating the prevalence of early childhood serious emotional/behavioral disorders: Challenges and recommendations. Public Health Rep. 2006, 121, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfeld, S.; Kvalsvig, A.; Incledon, E.; O’Connor, M.; Mensah, F. Predictors of mental health competence in a population cohort of Australian children. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2014, 68, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, A.D.; Mathers, C.D.; Ezzati, M.; Jamison, D.T.; Murray, C.J. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: Systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet 2006, 367, 1747–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, T.G.; Heron, J.; Golding, J.; Beveridge, M.; Glover, V. Maternal antenatal anxiety and children’s behavioural/emotional problems at 4 years. Report from the Avon longitudinal study of parents and children. Br. J. Psychiatry 2002, 180, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luoma, I.; Tamminen, T.; Kaukonen, P.; Laippala, P.; Puura, K.; Salmelin, R.; Almqvist, F. Longitudinal study of maternal depressive symptoms and child well-being. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2001, 40, 1367–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzmann, K.M.; Gaylord, N.K.; Holt, A.R.; Kenny, E.D. Child witnesses to domestic violence: A meta-analytic review. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 71, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groh, A.M.; Fearon, R.P.; van IJzendoorn, M.H.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; Roisman, G.I. Attachment in the early life course: Meta-analytic evidence for its role in socioemotional development. Child Dev. Perspect. 2017, 11, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, L.G.; Anthony, B.J.; Glanville, D.N.; Naiman, D.Q.; Waanders, C.; Shaffer, S. The relationships between parenting stress, parenting behaviour and preschoolers’ social competence and behaviour problems in the classroom. Infant Child Dev. Int. J. Res. Pract. 2005, 14, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repetti, R.L.; Taylor, S.E.; Seeman, T.E. Risky families: Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 330–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trent, M.; Dooley, D.G.; Douge, J. Aap section on adolescent health; Aap council on community pediatrics; Aap committee on adolescence. The impact of racism on child and adolescent health. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20191765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, M.; Moffitt, T.E.; Caspi, A. Gene–environment interplay and psychopathology: Multiple varieties but real effects. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2006, 47, 226–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimino, S.; Cerniglia, L.; Ballarotto, G.; Marzilli, E.; Pascale, E.; D’Addario, C.; Adriani, W.; Maremmani, A.G.I.; Tambelli, R. Children’s DAT1 polymorphism moderates the relationship between parents’ psychological profiles, children’s dat methylation, and their emotional/behavioral functioning in a normative sample. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgatroyd, C.; Spengler, D. Epigenetics of early child development. Front. Psychiatry 2011, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, D.; Hafekost, J.; Johnson, S.E.; Saw, S.; Buckingham, W.J.; Sawyer, M.G.; Ainley, J.; Zubrick, S.R. Key findings from the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2016, 50, 876–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. The Science of Early Childhood Development: Closing the Gap Between What We Know and What We Do; Harvard University, Center on the Developing Child: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Camilli, G.; Vargas, S.; Ryan, S.; Barnett, W.S. Meta-analysis of the effects of early education interventions on cognitive and social development. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2010, 112, 579–620. [Google Scholar]

- Oberklaid, F.; Baird, G.; Blair, M.; Melhuish, E.; Hall, D. Children’s health and development: Approaches to early identification and intervention. Arch. Dis. Child. 2013, 98, 1008–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, H.; Weiland, C.; Brooks-Gunn, J.; Burchinal, M.R.; Espinosa, L.M.; Gormley, W.T.; Ludwig, J.; Magnuson, K.A.; Phillips, D.; Zaslow, M.J. Investing in Our Future: The Evidence Base On Preschool Education; Society for Research in Child Development and Foundation for Child Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, W.S. Effectiveness of early educational intervention. Science 2011, 333, 975–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomajee, R.; El-Khoury, F.; Côté, S.; Van Der Waerden, J.; Pryor, L.; Melchior, M. Early childcare type predicts children’s emotional and behavioural trajectories into middle childhood. Data from the EDEN mother–child cohort study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2018, 72, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, G.J.; Sojourner, A.J. Can intensive early childhood intervention programs eliminate income- based cognitive and achievement gaps? J. Hum. Resour. 2013, 48, 945–968. [Google Scholar]

- Loeb, S.; Fuller, B.; Kagan, S.L.; Carrol, B. Child care in poor communities: Early learning effects of type, quality, and stability. Child Dev. 2004, 75, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnuson, K.A.; Meyers, M.K.; Ruhm, C.J.; Waldfogel, J. Inequality in preschool education and school readiness. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2004, 41, 115–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Early, D.M.; Pan, Y.; Maxwell, K.L.; Ponder, B.B. Improving teacher-child interactions: A randomized control trial of Making the Most of Classroom Interactions and My Teaching Partner professional development models. Early Child. Res. Q. 2017, 38, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howes, C.; Burchinal, M.; Pianta, R.; Bryant, D.; Early, D.; Clifford, R.; Barbarin, O. Ready to learn? children’s pre-academic achievement in pre-kindergarten programs. Early Child. Res. Q. 2008, 23, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashburn, A.J. Quality of social and physical environments in preschools and children’s development of academic, language, and literacy skills. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2008, 12, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponitz, C.C.; Rimm-Kaufman, S.E.; Grimm, K.J.; Curby, T.W. Kindergarten classroom quality, behavioral engagement, and reading achievement. School Psychol. Rev. 2009, 38, 102–120. [Google Scholar]

- Hamre, B.; Hatfield, B.; Pianta, R.; Jamil, F. Evidence for general and domain-specific elements of teacher-child interactions: Associations with preschool children’s development. Child Dev. 2014, 85, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justice, L.M.; Mashburn, A.J.; Hamre, B.K.; Pianta, R.C. Quality of language and literacy instruction in preschool classrooms serving at-risk pupils. Early Child. Res. Q. 2008, 23, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamre, B.K. Teachers’ Daily interactions with children: An essential ingredient in effective early childhood programs. Child Dev. Perspect. 2014, 8, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianta, R.C.; Barnett, W.S.; Burchinal, M.; Thornburg, K.R. The effects of preschool education: What we know, how public policy is or is not aligned with the evidence base, and what we need to know. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest Suppl. 2009, 10, 49–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuck, A.; Kammermeyer, G.; Roux, S. The reliability and structure of the classroom assessment scoring system in german pre-schools. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2016, 24, 873–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissberg, R.P.; Durlak, J.A.; Domitrovich, C.E.; Gullotta, T.P. Social and emotional learning: Past, present, and future. In Handbook of Social and Emotional Learning; Durlak, J.A., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bierman, K.L.; Motamedi, M. SEL programs for preschool children. In Handbook on Social and Emotional Learning: Research and Practice; Durlak, J.A., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. CASEL Guide: Effective Social and Emotional Learning Programs: Preschool and Elementary School Edition; CASEL: Chicago, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, A.; Blewitt, C.; Nolan, A.; Skouteris, H. Using Intervention Mapping for child development and wellbeing programs in early childhood education and care settings. Eval. Program Plan. 2018, 68, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew Eldrigde, L.K.; Markham, C.M.; Ruiter, R.A.C.; Fernàndez, M.E.; Kok, G.; Parcel, G.S. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, A.; Skouteris, H.; Nolan, A.; Hooley, M.; Cann, W.; Williams-Smith, J. Applying Intervention Mapping to develop an early childhood educators’ intervention promoting parent–child relationships. Early Child Dev. Care 2019, 189, 1033–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bestchance Child Family Care. The Cheshire School. Available online: https://www.bestchance.org.au/cheshire-school/ (accessed on 4 November 2019).

- Council of Australian Governments (COAG). National Quality Standard for Early Childhood Education and School Age Care; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2009.

- Council of Australian Governments (COAG). Belonging, Being and Becoming: The Early Years Learning Framework for Australia; Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workforce Relations: Canberra, Australia, 2009.

- Shepley, C.; Grisham-Brown, J. Multi-tiered systems of support for preschool-aged children: A review and meta-analysis. Early Child. Res. Q. 2019, 47, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, M.T.; Domitrovich, C.E.; Weissberg, R.P.; Durlak, J.A. Social and emotional learning as a public health approach to education. Future Child. 2017, 27, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macklem, G.L. Evidence-based tier 1, tier 2, and tier 3 mental health interventions in schools. In Evidence-Based School Mental Health Services; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Blewitt, C.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M.; Nolan, A.; Bergmeier, H.; Vicary, D.; Huang, T.; McCabe, P.; McKay, T.; Skouteris, H. Social and emotional learning associated with universal curriculum-based interventions in early childhood education and care centers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e185727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blewitt, C.; O’Connor, A.; Morris, H.; May, T.; Mousa, A.; Bergmeier, H.; Nolan, A.; Jackson, K.; Barrett, H.; Skouteris, H. A systematic review of targeted social and emotional learning interventions in early childhood education and care settings. Early Child Dev. Care 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blewitt, C.; O’Connor, A.; May, T.; Morris, H.; Mousa, A.; Bergmeier, H.; Jackson, K.; Barrett, H.; Skouteris, H. Strengthening the social and emotional skills of pre-schoolers with mental health and developmental challenges in inclusive early childhood education and care settings: A narrative review of educator-led interventions. Early Child Dev. Care 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Morris, P.A. The bioecological model of human development. In Handbook of Child Psychology, Volume 1: Theoretical Models of Human Development, 6th ed.; Damon, W., Lerner, M., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 793–828. [Google Scholar]

- Dialogic Learning. Available online: https://dialogiclearning.com/ (accessed on 4 November 2019).

- Egger, H.L.; Angold, A. Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: Presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2006, 47, 313–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, A.; Raban, B. Reflection on one’s practice: Research about theories espoused by practitioners-the grand and the personal. In The Routledge International Handbook of Philosophies and Theories of Early Childhood Education and Care; David, T., Goouch, K., Powell, S., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tournaki, N.; Podell, D.M. The impact of student characteristics and teacher efficacy on teachers’ predictions of student success. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2005, 21, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, M.B. Characteristics of teachers who talk the DAP talk and walk the DAP walk. J. Res. Child. Educ. 1999, 13, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantuzzo, J.; Perlman, S.; Sproul, F.; Minney, A.; Perry, M.A.; Li, F. Making visible teacher reports of their teaching experiences: The early childhood teacher experiences scale. Psychol. Sch. 2012, 49, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goroshit, M.; Hen, M. Does emotional self-efficacy predict teachers’ self-efficacy and empathy? J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2014, 2, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerde, H.K.; Pierce, S.J.; Lee, K.; Van Egeren, L.A. Early childhood educators’ self-efficacy in science, math, and literacy instruction and science practice in the classroom. Early Educ. Dev. 2018, 29, 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartuli, S. How early childhood teacher beliefs vary across grade level. Early Child. Res. Q. 1999, 14, 489–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P.A.; Greenberg, M.T. The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 2009, 79, 491–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinsser, K.M.; Bailey, C.S.; Curby, T.W.; Denham, S.A.; Bassett, H.H. Exploring the predictable classroom: Preschool teacher stress, emotional supportiveness, and students’ social-emotional behavior in private and Head Start classrooms. NHSA Dialog 2013, 16, 90–108. [Google Scholar]

- Blewitt, C.; Morris, H.; Nolan, A.; Jackson, K.; Barrett, H.; Skouteris, H. Strengthening the quality of educator-child interactions in early childhood education and care settings: A conceptual model to improve mental health outcomes for preschoolers. Early Child Dev. Care 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamre, B.K.; Pianta, R.C. Learning opportunities in preschool and early elementary classrooms. In School Readiness and the Transition to Kindergarten in the Era of Accountability; Pianta, R., Cox, M., Snow, K., Eds.; Brookes: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2007; pp. 49–84. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, L.; Dunlap, G.; Hemmeter, M.L.; Joseph, G.E.; Strain, P.S. The teaching pyramid: A model for supporting social competence and preventing challenging behavior in young children. Young Child. 2003, 58, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hemmeter, M.L.; Ostrosky, M.; Fox, L. Social and emotional foundations for early learning: A conceptual model for intervention. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 35, 583–601. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, T.S.; Skinner, C.H. Functional behavioral assessment: Principles, procedures, and future directions. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 30, 156–172. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, B.J.; Krajcik, J. What does it mean to create sustainable science curriculum innovations? A commentary. Sci. Educ. 2003, 87, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, P.C.; Altamura, M. Empirically valid strategies to improve social and emotional competence of preschool children. Psychol. Sch. 2011, 48, 513–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, M.M.; Tominey, S.L.; Schmitt, S.A.; Duncan, R. SEL interventions in early childhood. Future Child. 2017, 27, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, H.S.; Kholoptseva, J.; Oh, S.S.; Shonkoff, J.P.; Yoshikawa, H.; Duncan, G.J.; Magnuson, K.A. Maximizing the potential of early childhood education to prevent externalizing behavior problems: A meta-analysis. J. Sch. Psychol. 2015, 53, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, C.D.; Linting, M.; Vermeer, H.J.; Ijzendoorn, M.H. Do intervention programs in child care promote the quality of caregiver-child interactions? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Prev. Sci. 2016, 17, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartmel, J.; Macfarlane, K.; Nolan, A. Looking to the future: Producing transdisciplinary professionals for leadership in early childhood settings. Early Years 2013, 33, 398–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayler, C.; Ishimine, K.; Cloney, D.; Cleveland, G.; Thorpe, K. The quality of early childhood education and care services in Australia. Australas. J. Early Child. 2013, 38, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumsion, J.; Barnes, S.; Cheeseman, S.; Harrison, L.; Kennedy, A.; Stonehouse, A. Insider perspectives on developing belonging, being & becoming: The early years learning framework for Australia. Australas. J. Early Child. 2009, 34, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Tayler, C. Changing policy, changing culture: Steps toward early learning quality improvement in Australia. Int. J. Early Child. 2011, 43, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beijaard, D.; Korthagen, F.; Verloop, N. Understanding how teachers learn as a prerequisite for promoting teacher learning. Teach. Teach. 2007, 13, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughran, J.; Mitchell, I.; Mitchell, J. Attempting to document teachers’ professional knowledge. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2003, 16, 853–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, A.; Nolan, A.; Bergmeier, H.; Williams-Smith, J.; Skouteris, H. Early childhood educators’ perceptions of parent-child relationships: A qualitative study. Australas. J. Early Child. 2018, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, U.; Kim, C.; Cako, A.; Gagliardi, A.R. Engaging stakeholders in the co-development of programs or interventions using intervention mapping: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0209826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penuel, W.R.; Allen, A.-R.; Coburn, C.E.; Farrell, C. Conceptualizing research–practice partnerships as joint work at boundaries. J. Educ. Stud. Placed Risk (JESPAR) 2015, 20, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coburn, C.E.; Penuel, W.R. Research–practice partnerships in education: Outcomes, dynamics, and open questions. Educ. Res. 2016, 45, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Könings, K.D.; Seidel, T.; van Merriënboer, J.J. Participatory design of learning environments: Integrating perspectives of students, teachers, and designers. Instr. Sci. 2014, 42, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penuel, W.R.; Fishman, B.J.; Haugan Cheng, B.; Sabelli, N. Organizing research and development at the intersection of learning, implementation, and design. Educ. Res. 2011, 40, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, A.; Nolan, A.; Bergmeier, H.; Hooley, M.; Olsson, C.; Cann, W.; Williams-Smith, J.; Skouteris, H. Early childhood education and care educators supporting parent-child relationships: A systematic literature review. Early Years 2017, 37, 400–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downer, J.; Sabol, T.J.; Hamre, B. Teacher-child interactions in the classroom: Toward a theory of within and cross-domain links to children’s developmental outcomes. Early Educ. Dev. 2010, 21, 699–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of SEL Program | Description of Review | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Universal, curriculum-based SEL interventions [57] | Systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of 79 experimental or quasi-experimental studies (391 effect sizes) that examined the impact of SEL intervention on children’s social, emotional, behavioural, and early learning outcomes |

|

| Universal, curriculum-based SEL interventions | Systematic review of 16 studies (RCT, quasi-experimental, within-group designs) that examined the impact of SEL intervention on teaching quality and practice |

|

| Tier 2 (targeted) SEL intervention [58] | Systematic review of 19 studies (RCT, quasi-experimental, single-subject designs) that examined the impact of Tier 2 SEL intervention on children’s social, emotional, and behavioural outcomes |

|

| Tier 3 (intensive) SEL intervention [59] | Narrative review of 19 studies (RCT, quasi-experimental, single-subject, within-group designs) that examined the impact of Tier 3 SEL intervention on children’s social, emotional, and behavioural outcomes |

|

| Program Goal | Target Group | Program Outcome | Performance Objectives (PO) |

|---|---|---|---|

| To strengthen the everyday interactions between educators, children, and families so that early childhood educators can support and foster all children’s social and emotional development. | Educator (Individual) | Educators utilise strategies that target children’s social and emotional skill development during their everyday interactions and practice | Educators will: PO1: Develop nurturing, consistent, and responsive relationships with children PO2: Understand early childhood social, emotional, and behavioural development PO3: Identify the social-emotional strengths, challenges, and opportunities for children in their group PO4: Build knowledge of strategies, techniques, and language that supports young children’s social and emotional learning and positive mental health PO5: Respond effectively to opportunities to support social and emotional skill growth by applying strategies PO6: Engage with caregivers around strategies |

| Peers/Early Years Team (Interpersonal) | Educators collaborate to establish goals, share knowledge and learning, and monitor progress | Early Years Teams will: PO7: Set goals for individual children and groups PO8: Encourage and support each other to implement strategies that target children’s social and emotional skill development P09: Reflect on any changes in children’s behaviour and social-emotional competencies as a result of strategies P10: Reflect on any changes in educators’ own practice as a result of strategies | |

| ECEC Service Providers (Organisational) | Service providers encourage ECEC staff to engage in professional development | Service Providers will: P11: Afford time and encouragement for educators to engage in learning, reflection and discussion, and embed strategies into their practice and routines |

| Educator Performance Objectives (PO) | Key Determinants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge (K) | Belief (B) | Skill (SK) | Self-Efficacy (SE) | Social-Emotional Competency (SO) | |

| PO1: Develop nurturing, consistent, and responsive relationships with children | K1.1: Educators know how the educator–child relationship influences children’s behaviour and wellbeing K1.2: Educators understand factors that influence the educator–child relationship | B1.1: Recognise the importance of positive educator–child relationships for children’s mental health | SK1.1: Engage, interact, and respond sensitively to young children SK1.2 Share information and experiences through interactions SK1.3: Recognise, understand, and respond appropriately to social and emotional cues | SE1.1: Express confidence in ability to form positive relationships with children | SO1.1: Recognise own emotions and behaviour SO.1.2: Understand and manage own emotional responses |

| PO2: Understand early childhood social, emotional, and behavioural development | K2.1: Educators can describe social-emotional milestones that typically emerge in early childhood K2.2: Educators know the risk and protective factors for healthy social-emotional development K2.3: Educators can identify the outcomes associated with early social and emotional difficulties | B2.1: Recognise the importance of social and emotional competencies for learning, health, and wellbeing | SK2.1: Integrate knowledge gained through experience, professional development, and informal learning SK2.2: Build knowledge by working with peers and other professionals | SE2.1: Confidence in ability to gather, retain, and apply information | SO2.1: Recognise how own experiences, background, and culture can influence understanding and perceptions of child development |

| PO 3: Identify the social-emotional strengths, challenges, and opportunities for children in their group | K3.1: Educators recognise behaviours that suggest healthy social-emotional development K3.2: Educators can describe common form (types) of challenging behaviours K3.3: Educators can describe possible functions (purpose) of behaviour | B3.1: Belief that ECEC educators play an important role in observing and understanding child behaviour | SK3.1: Identify form and function of behaviours SK3.2: Collect and interpret information from different sources (e.g., observation, caregiver, other early years professionals) | SE.3.1: Belief in ability to understand and respond to children’s behaviour | SO3.1: Recognise how own experiences, background, and culture can influence perception child behaviour |

| PO4: Build knowledge of strategies, techniques, and language that supports young children’s social and emotional learning | K4.1: Educator knows how the early years environment, caregiver–child, and child–child interactions can influence social-emotional development K4.2: Educators understand theories and principles that underpin strategies K4.3: Educators understand the purpose and rationale of strategies K4.4: Educators know how to use the strategy effectively | B4.1: Perceive ECEC educator is responsible for supporting social-emotional skill development B4.2: Recognise educator–child interactions can have therapeutic benefit B4.3: Recognise early years environment can influence children’s social and emotional skill B4.4: Belief that strategies can build upon educators’ current skill and knowledge | SK4.1: Integrate new knowledge (strategies) with current knowledge and practice | SE4.1: Express confidence in ability to use strategies during every day practice | |

| PO5: Respond effectively to opportunities to support social and emotional skill growth by applying strategies | K5.1: Educator can identify suitable strategies based on needs and challenges of child/group | B5.1: Increased recognition that every interaction is an opportunity to nurture children’s social and emotional skill | SK5.1: Identify opportunities to embed strategies into daily interactions and practice SK5.2: Implement strategies | SE5.1: Belief in ability to implement strategies | SO5.1: Recognise how own experiences, background. and culture can influence interactions with children |

| PO6: Engage with caregivers around strategies | K6.1: Educator can describe approaches that strengthen children’s social-emotional skills | B6.1: Belief that educator and caregiver should work in partnership to support children’s social-emotional development | SK6.1: Ability to engage caregivers in conversation about their child’s development SK6.2: Ability to share and discuss strategies | SE6.1: Confidence in ability to work in partnership with caregivers | SO6.1: Recognise how own experiences, background, and culture can influence interactions with caregivers and families |

| Level of Intervention | Determinant of Educator Behaviour | Change Objective (s) | Method (Related Theory) | Specific Activities in Cheshire SEED |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educator (Individual) | Knowledge | K1.1, 1.2, 2.1, 2,2, 2.3, 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, 4.1, 4.2, 4.3, 4.4, 6.1 | Active Learning (SCT, SLT, ELM) | Interactive modules Goal setting, observation, and reflection Interactive case studies |

| K1.1, 1.2, 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, 4.1 | Consciousness Raising (TTM) | Written and video content | ||

| K5.1 | Tailoring (TTM) | Tailored SEL strategies based on user inputs | ||

| K4.1, 4.2, 4.3, 4.4, 5.1 | Discussion (ELM) | Moderated online communities of practice forums Webinar In-room consultation | ||

| Belief | B1.1, 2.1, 3.1, 4.1, 4.2, 4.3, 4.4, 5.1, 6.1, | Elaboration (TIP, ELM) | SEL strategies Video by coaches | |

| B3.1, 4.1, 4.2, 4.3, 4.4, 5.1 | Argument/Persuasive Communication (ELM, TPC) | Video by coaches | ||

| B4.2, 4.3, 4.4, 5.1 | Direct Experience (TL) | SEL strategies In-room consultation | ||

| Skill | SK1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 2.1, 2.2, 3.1, 3.2, 4.1, 5.1, 5.2, 6.1, 6.2 | Active Learning (SCT, SLT, ELM) | Interactive modules Goal setting, observation, and reflection Interactive case studies Parent handouts | |

| SK5.1, 5.2, 6.1, 6.2 | Individualisation (TTM) | In-room consultation Communities of practice forums Webinars | ||

| SK1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 3.1, 5.1, 5.2 | Verbal Persuasion (SCT) | Video by coaches | ||

| SK5.1 | Goal Setting (TSR) | Goal setting, observation, and reflection | ||

| SK3.1, 4.1, 5.1, 5.2 | Modelling (SCT) | Video exemplars Examples of language and phrases In-room consultation Case studies | ||

| SK3.1, 3.2, 4.1, 5.1, 5.2 | Participatory Problem Solving | Functional Behaviour Analysis Individualised plans | ||

| Self-Efficacy | SE1.1, 3.1, 4.1, 5.1 | Guided Practice and Feedback (SCT, TSR) | In-room consultation | |

| SE1.1, 2.1, 3.1, 4.1, 5.1, 6.1 | Discussion (ELM) | Communities of practice forums Webinars | ||

| Social-Emotional Competence | SO1.1, 1.2, 2.1, 3.1, 5.1, 6.1 | Guided Practice and Feedback (SCT) | In-room consultation | |

| SO1.1, 1.2, 2.1, 3.1, 5.1, 6.1 | Consciousness Raising (TTM) | Written and video content |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blewitt, C.; Morris, H.; Jackson, K.; Barrett, H.; Bergmeier, H.; O’Connor, A.; Mousa, A.; Nolan, A.; Skouteris, H. Integrating Health and Educational Perspectives to Promote Preschoolers’ Social and Emotional Learning: Development of a Multi-Faceted Program Using an Intervention Mapping Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 575. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020575

Blewitt C, Morris H, Jackson K, Barrett H, Bergmeier H, O’Connor A, Mousa A, Nolan A, Skouteris H. Integrating Health and Educational Perspectives to Promote Preschoolers’ Social and Emotional Learning: Development of a Multi-Faceted Program Using an Intervention Mapping Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(2):575. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020575

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlewitt, Claire, Heather Morris, Kylie Jackson, Helen Barrett, Heidi Bergmeier, Amanda O’Connor, Aya Mousa, Andrea Nolan, and Helen Skouteris. 2020. "Integrating Health and Educational Perspectives to Promote Preschoolers’ Social and Emotional Learning: Development of a Multi-Faceted Program Using an Intervention Mapping Approach" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 2: 575. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020575

APA StyleBlewitt, C., Morris, H., Jackson, K., Barrett, H., Bergmeier, H., O’Connor, A., Mousa, A., Nolan, A., & Skouteris, H. (2020). Integrating Health and Educational Perspectives to Promote Preschoolers’ Social and Emotional Learning: Development of a Multi-Faceted Program Using an Intervention Mapping Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), 575. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020575