World Trade Center Health Program: First Decade of Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. World Trade Center Health Program (WTCHP)

2.1. WTCHP Data Centers and Clinical Centers of Excellence

2.2. WTCHP Research Populations

2.3. Environmental Exposure

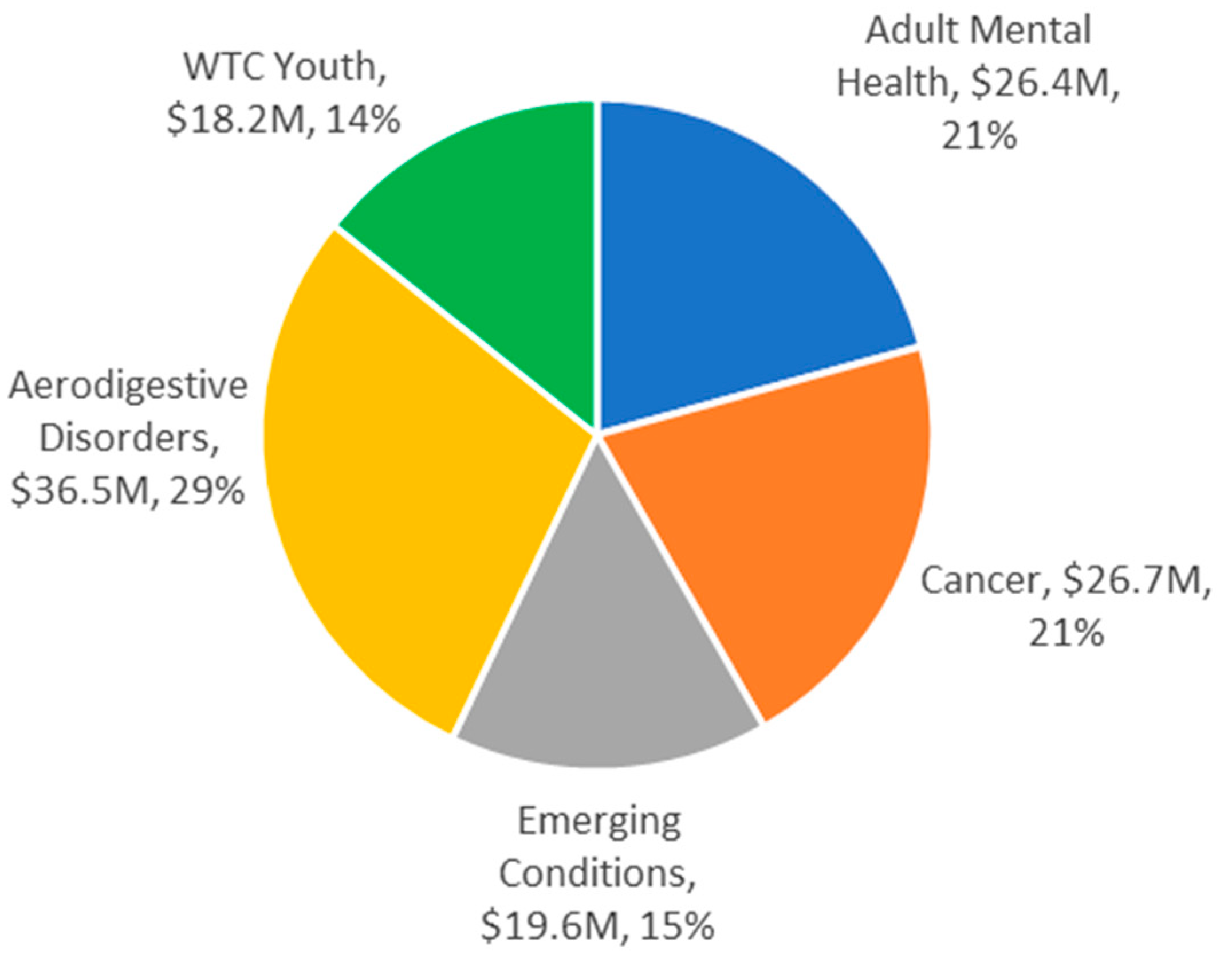

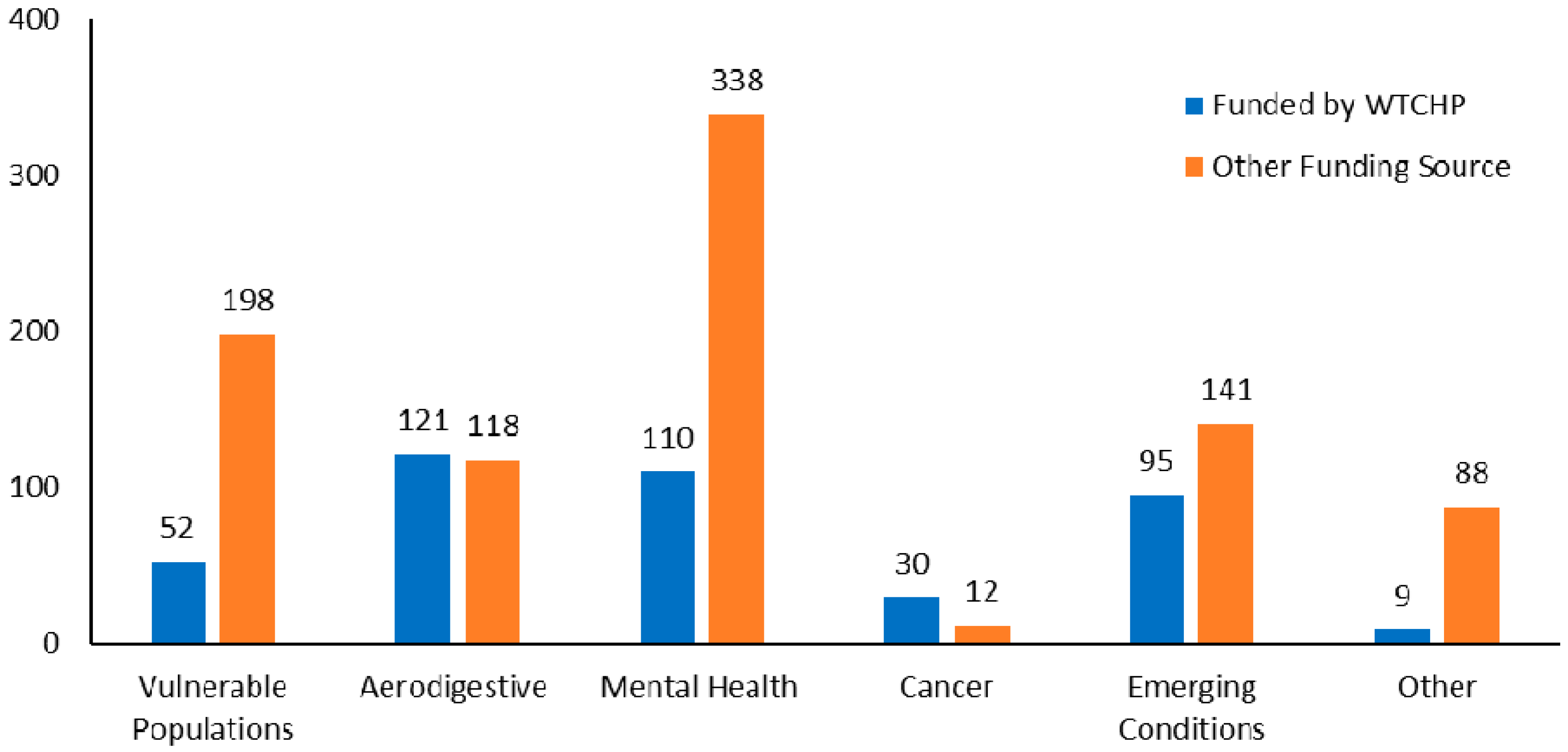

3. Research Portfolio

3.1. Solicitation and Award

3.2. Stakeholder Involvement in Research Planning

3.3. Description of WTC Research

3.3.1. Aerodigestive Disorders

3.3.2. Mental Health Conditions

3.3.3. Cancer

3.3.4. Vulnerable Populations

Prenatal Exposures

Childhood and Adolescence

3.3.5. Emerging Conditions

Autoimmune Disease

Cardiovascular Disease

Cognitive Impairment

4. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murphy, J.; Brackbill, R.M.; Thalji, L.; Dolan, M.; Pulliam, P.; Walker, D.J. Measuring and maximizing coverage in the World Trade Center Health Registry. Stat. Med. 2007, 26, 1688–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, J.; Webber, M.P.; Zeig-Owens, R.; Vossbrinck, M.; Singh, A.; Kelly, K.; Prezant, D.J. FDNY and 9/11: Clinical services and health outcomes in World Trade Center-exposed firefighters and EMS workers from 2001 to 2016. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2016, 59, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasaro, C.R.; Holden, W.L.; Berman, K.D.; Crane, M.A.; Kaplan, J.R.; Lucchini, R.G.; Luft, B.J.; Moline, J.M.; Teitelbaum, S.L.; Tirunagari, U.S.; et al. Cohort profile: World Trade Center Health Program General Responder Cohort. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landrigan, P.J.; Lioy, P.J.; Thurston, G.; Berkowitz, G.; Chen, L.C.; Chillrud, S.N.; Gavett, S.H.; Georgopoulos, P.G.; Geyh, A.S.; Levin, S.; et al. Health and environmental consequences of the World Trade Center disaster. Environ. Health Perspect. 2004, 112, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lioy, P.J.; Georgopoulos, P. The anatomy of the exposures that occurred around the World Trade Center site: 9/11 and beyond. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1076, 54–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lioy, P.J.; Weisel, C.P.; Millette, J.R.; Eisenreich, S.; Vallero, D.; Offenberg, J.; Buckley, B.; Turpin, B.; Zhong, M.; Cohen, M.D.; et al. Characterization of the dust/smoke aerosol that settled east of the World Trade Center (WTC) in lower Manhattan after the collapse of the WTC 11 September 2001. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002, 110, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, J.K.; Chen, L.C.; Cohen, M.D.; Chee, G.R.; Prophete, C.M.; Haykal-Coates, N.; Wasson, S.J.; Conner, T.L.; Costa, D.L.; Gavett, S.H. Chemical analysis of World Trade Center fine particulate matter for use in toxicologic assessment. Environ. Health Perspect. 2003, 111, 972–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIOSH. WTC Health Program Publications. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/ResearchGateway/Publications (accessed on 22 July 2020).

- Friedman, S.M.; Farfel, M.R.; Maslow, C.B.; Cone, J.E.; Brackbill, R.M.; Stellman, S.D. Comorbid persistent lower respiratory symptoms and posttraumatic stress disorder 5–6 years post-9/11 in responders enrolled in the World Trade Center Health Registry. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2013, 56, 1251–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotov, R.; Bromet, E.J.; Schechter, C.; Broihier, J.; Feder, A.; Friedman-Jimenez, G.; Gonzalez, A.; Guerrera, K.; Kaplan, J.; Moline, J.; et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and the risk of respiratory problems in World Trade Center responders: Longitudinal test of a pathway. Psychosom. Med. 2015, 77, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luft, B.J.; Schechter, C.; Kotov, R.; Broihier, J.; Reissman, D.; Guerrera, K.; Udasin, I.; Moline, J.; Harrison, D.; Friedman-Jimenez, G.; et al. Exposure, probable PTSD and lower respiratory illness among World Trade Center rescue, recovery and clean-up workers. Psychol. Med. 2012, 42, 1069–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niles, J.K.; Webber, M.P.; Gustave, J.; Cohen, H.W.; Zeig-Owens, R.; Kelly, K.J.; Glass, L.; Prezant, D.J. Comorbid trends in World Trade Center cough syndrome and probable posttraumatic stress disorder in firefighters. Chest 2011, 140, 1146–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, H.P.; Ekenga, C.C.; Cone, J.E.; Brackbill, R.M.; Farfel, M.R.; Stellman, S.D. Co-occurring lower respiratory symptoms and posttraumatic stress disorder 5 to 6 years after the World Trade Center terrorist attack. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 1964–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisnivesky, J.P.; Teitelbaum, S.L.; Todd, A.C.; Boffetta, P.; Crane, M.; Crowley, L.; de la Hoz, R.E.; Dellenbaugh, C.; Harrison, D.; Herbert, R.; et al. Persistence of multiple illnesses in World Trade Center rescue and recovery workers: A cohort study. Lancet 2011, 378, 888–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Brackbill, R.M.; Stellman, S.D.; Farfel, M.R.; Miller-Archie, S.A.; Friedman, S.; Walker, D.J.; Thorpe, L.E.; Cone, J. Gastroesophageal reflux symptoms and comorbid asthma and posttraumatic stress disorder following the 9/11 terrorist attacks on World Trade Center in New York City. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 106, 1933–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, H.T.; Osahan, S.; Li, J.; Stein, C.R.; Friedman, S.M.; Brackbill, R.M.; Cone, J.E.; Gwynn, C.; Mok, H.K.; Farfel, M.R. Persistent mental and physical health impact of exposure to the 11 September 2001 World Trade Center terrorist attacks. Environ. Health 2019, 18, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banauch, G.; Mclaughlin, M.; Hirschorn, R.; Corrigan, M.; Kelly, K.; Prezant, D. (MMWR) Injuries and illnesses among New York City Fire Department rescue workers after responding to the World Trade Center attacks. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2002, 51, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Prezant, D.J.; Weiden, M.; Banauch, G.I.; McGuinness, G.; Rom, W.N.; Aldrich, T.K.; Kelly, K.J. Cough and bronchial responsiveness in firefighters at the World Trade Center site. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 806–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weakley, J.; Webber, M.P.; Gustave, J.; Kelly, K.; Cohen, H.W.; Hall, C.B.; Prezant, D.J. Trends in respiratory diagnoses and symptoms of firefighters exposed to the World Trade Center disaster: 2005–2010. Prev. Med. 2011, 53, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, M.P.; Gustave, J.; Lee, R.; Niles, J.K.; Kelly, K.; Cohen, H.W.; Prezant, D.J. Trends in respiratory symptoms of firefighters exposed to the world trade center disaster: 2001–2005. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 975–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, T.K.; Gustave, J.; Hall, C.B.; Cohen, H.W.; Webber, M.P.; Zeig-Owens, R.; Cosenza, K.; Christodoulou, V.; Glass, L.; Al-Othman, F.; et al. Lung function in rescue workers at the World Trade Center after 7 years. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1263–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, T.K.; Vossbrinck, M.; Zeig-Owens, R.; Hall, C.B.; Schwartz, T.M.; Moir, W.; Webber, M.P.; Cohen, H.W.; Nolan, A.; Weiden, M.D.; et al. Lung function trajectories in WTC-exposed NYC Firefighters over 13 years: The roles of smoking and smoking cessation. Chest 2016, 149, 1419–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldrich, T.K.; Weakley, J.; Dhar, S.; Hall, C.B.; Crosse, T.; Banauch, G.I.; Weiden, M.D.; Izbicki, G.; Cohen, H.W.; Gupta, A.; et al. Bronchial reactivity and lung function after World Trade Center exposure. Chest 2016, 150, 1333–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vossbrinck, M.; Zeig-Owens, R.; Hall, C.B.; Schwartz, T.; Moir, W.; Webber, M.P.; Cohen, H.W.; Nolan, A.; Weiden, M.D.; Christodoulou, V.; et al. Post-9/11/2001 lung function trajectories by sex and race in World Trade Center-exposed New York City emergency medical service workers. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 74, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reibman, J.; Liu, M.; Cheng, Q.; Liautaud, S.; Rogers, L.; Lau, S.; Berger, K.I.; Goldring, R.M.; Marmor, M.; Fernandez-Beros, M.E.; et al. Characteristics of a residential and working community with diverse exposure to World Trade Center dust, gas, and fumes. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2009, 51, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reibman, J.; Lin, S.; Hwang, S.A.; Gulati, M.; Bowers, J.A.; Rogers, L.; Berger, K.I.; Hoerning, A.; Gomez, M.; Fitzgerald, E.F. The World Trade Center residents’ respiratory health study: New-onset respiratory symptoms and pulmonary function. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, H.T.; Friedman, S.M.; Reibman, J.; Goldring, R.M.; Miller Archie, S.A.; Ortega, F.; Alper, H.; Shao, Y.; Maslow, C.B.; Cone, J.E.; et al. Risk factors for persistence of lower respiratory symptoms among community members exposed to the 2001 World Trade Center terrorist attacks. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 74, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowell, A.; Suarez-Jimenez, B.; Helpman, L.; Zhu, X.; Durosky, A.; Hilburn, A.; Schneier, F.; Gross, R.; Neria, Y. 9/11-related PTSD among highly exposed populations: A systematic review 15 years after the attack. Psychol. Med. 2017, 48, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, B.J.; DeVoe, E.R.; Stuber, J.; Schiff, M.; Klein, T.P.; Fairbrother, G. Psychological impact of terrorism on children and families in the United States. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2004, 9, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bills, C.B.; Levy, N.A.; Sharma, V.; Charney, D.S.; Herbert, R.; Moline, J.; Katz, C.L. (Review) Mental health of workers and volunteers responding to events of 9/11: Review of the literature. Mt. Sinai J. Med. 2008, 75, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Tarigan, L.H.; Bromet, E.J.; Kim, H. World Trade Center disaster exposure-related probable posttraumatic stress disorder among responders and civilians: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neria, Y.; DiGrande, L.; Adams, B.G. Posttraumatic stress disorder following the 11 September 2001, terrorist attacks: A review of the literature among highly exposed populations. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 429–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlenger, W.E.; Caddell, J.M.; Ebert, L.; Jordan, B.K.; Rourke, K.M.; Wilson, D.; Thalji, L.; Dennis, J.M.; Fairbank, J.A.; Kulka, R.A. Psychological reactions to terrorist attacks: Findings from the National Study of Americans’ Reactions to September 11. JAMA 2002, 288, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galea, S.; Ahern, J.; Resnick, H.; Kilpatrick, D.; Bucuvalas, M.; Gold, J.; Vlahov, D. Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 982–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoagwood, K.E. Implementation of CBT for youth affected by the World Trade Center disaster: Matching need to treatment intensity and reducing trauma symptoms. J. Trauma Stress 2010, 23, 699–707. [Google Scholar]

- Costantino, G.; Primavera, L.H.; Malgady, R.G.; Costantino, E. Culturally oriented trauma treatments for Latino children Post 9/11. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2014, 7, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Difede, J.; Malta, L.S.; Best, S.; Henn-Haase, C.; Metzler, T.; Bryant, R.; Marmar, C. A randomized controlled clinical treatment trial for World Trade Center attack-related PTSD in disaster workers. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2007, 195, 861–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Difede, J.; Cukor, J.; Jayasinghe, N.; Patt, I.; Jedel, S.; Spielman, L.; Giosan, C.; Hoffman, H.G. Virtual reality exposure therapy for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder following 11 September 2001. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2007, 68, 1639–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Difede, J.; Cukor, J.; Patt, I.; Giosan, C.; Hoffman, H. The application of virtual reality to the treatment of PTSD following the WTC attack. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1071, 500–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, J.T.; Malta, L.S.; Martin, A.; Davis, L.; Cloitre, M. The flexible application of a manualized treatment for PTSD symptoms and functional impairment related to the 9/11 World Trade Center attack. Behav. Res. 2007, 45, 1419–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneier, F.R.; Neria, Y.; Pavlicova, M.; Hembree, E.; Suh, E.J.; Amsel, L.; Marshall, R.D. Combined prolonged exposure therapy and paroxetine for PTSD related to the World Trade Center attack: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 2012, 169, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, S.M.; Rogers, S.; Knipe, J.; Colelli, G. EMDR therapy following the 9/11 terrorist attacks: A community-based intervention project in New York City. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2005, 12, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.J.; Charlson, F.J.; Norman, R.E.; Patten, S.B.; Freedman, G.; Murray, C.J.L.; Vos, T.; Whiteford, H.A. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salguero, J.M.; Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Iruarrizaga, I.; Cano-Vindel, A.; Galea, S. Major depressive disorder following terrorist attacks: A systematic review of prevalence, course and correlates. BMC Psychiatry 2011, 11, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, C.S.; Ursano, R.J.; Wang, L. Acute stress disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression in disaster of rescue workers. Am. J. Psychiatry 2004, 161, 1370–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kukihara, H.; Yamawaki, N.; Uchiyama, K.; Arai, S.; Horikawa, E. Trauma, depression, and resilience of earthquake/tsunami/nuclear disaster survivors of Hirono, Fukushima, Japan. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2014, 68, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonde, J.P.; Utzon-Frank, N.; Bertelsen, M.; Borritz, M.; Eller, N.H.; Nordentoft, M.; Olesen, K.; Rod, N.H.; Rugulies, R. Risk of depressive disorder following disasters and military deployment: Systematic review with meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2016, 208, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Person, C.; Tracy, M.; Galea, S. Risk factors for depression after a disaster. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2006, 194, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapp, L.C.; Baron, S.; Bernard, B.; Driscoll, R.; Mueller, C.; Wallingford, K. Physical and mental health symptoms among NYC transit workers seven and one-half months after the WTC attacks. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2005, 47, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, R.; Neria, Y.; Tao, X.G.; Massa, J.; Ashwell, L.; Davis, K.; Geyh, A. Posttraumatic stress disorder and other psychological sequelae among World Trade Center clean up and recovery workers. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1071, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, A.; Tracy, M.; Beard, J.R.; Vlahov, D.; Galea, S. Patterns and predictors of trajectories of depression after an urban disaster. Ann. Epidemiol. 2009, 19, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, J.R.; Tracy, M.; Vlahov, D.; Galea, S. Trajectory and socioeconomic predictors of depression in a prospective study of residents of New York City. Ann. Epidemiol. 2008, 18, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galatzer-Levy, I.R.; Huang, S.H.; Bonanno, G.A. Trajectories of resilience and dysfunction following potential trauma: A review and statistical evaluation. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 63, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, H.T.; Stein, C.R.; Li, J.; Cone, J.E.; Stayner, L.; Hadler, J.L.; Brackbill, R.M.; Farfel, M.R. Mortality among rescue and recovery workers and community members exposed to the 11 September 2001 World Trade Center terrorist attacks, 2003–2014. Environ. Res. 2018, 163, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeig-Owens, R.; Webber, M.P.; Hall, C.B.; Schwartz, T.; Jaber, N.; Weakley, J.; Rohan, T.E.; Cohen, H.W.; Derman, O.; Aldrich, T.K.; et al. Early assessment of cancer outcomes in New York City firefighters after the 9/11 attacks: An observational cohort study. Lancet 2011, 378, 898–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moir, W.; Zeig-Owens, R.; Daniels, R.D.; Hall, C.B.; Webber, M.P.; Jaber, N.; Yiin, J.H.; Schwartz, T.; Liu, X.; Vossbrinck, M.; et al. Post-9/11 cancer incidence in World Trade Center-exposed New York City firefighters as compared to a pooled cohort of firefighters from San Francisco, Chicago and Philadelphia (9/11/2001–2009). Am. J. Ind. Med. 2016, 59, 722–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solan, S.; Wallenstein, S.; Shapiro, M.; Teitelbaum, S.L.; Stevenson, L.; Kochman, A.; Kaplan, J.; Dellenbaugh, C.; Kahn, A.; Biro, F.N.; et al. Cancer incidence in world trade center rescue and recovery workers, 2001–2008. Environ. Health Perspect. 2013, 121, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, M.Z.; Wallenstein, S.R.; Dasaro, C.R.; Lucchini, R.G.; Sacks, H.S.; Teitelbaum, S.L.; Thanik, E.S.; Crane, M.A.; Harrison, D.J.; Luft, B.J.; et al. Cancer in general responders participating in World Trade Center health programs, 2003–2013. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2020, 4, pkz090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cone, J.E.; Kahn, A.R.; Brackbill, R.M.; Farfel, M.R.; Greene, C.M.; Hadler, J.L.; Stayner, L.T.; Stellman, S.D. Association between World Trade Center exposure and excess cancer risk. JAMA 2012, 308, 2479–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Brackbill, R.M.; Liao, T.S.; Qiao, B.; Cone, J.E.; Farfel, M.R.; Hadler, J.L.; Kahn, A.R.; Konty, K.J.; Stayner, L.T.; et al. Ten-year cancer incidence in rescue/recovery workers and civilians exposed to the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2016, 59, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graber, J.M.; Chuang, C.T.; Ward, C.L.; Black, K.; Udasin, I.G. Head and neck cancer in World Trade Center responders: A case series. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 60, e439–e444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graber, J.M.; Harris, G.; Black, K.; Lucchini, R.G.; Giuliano, A.R.; Dasaro, C.R.; Shapiro, M.; Steinberg, M.B.; Crane, M.A.; Moline, J.M.; et al. Excess HPV-related head and neck cancer in the world trade center health program general responder cohort. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 145, 1504–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashim, D.; Boffetta, P.; Galsky, M.; Oh, W.; Lucchini, R.; Crane, M.; Luft, B.; Moline, J.; Udasin, I.; Harrison, D.; et al. Prostate cancer characteristics in the World Trade Center cohort, 2002–2013. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2016, 27, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Y.; Wang, L.; Yu, H.; Alpert, N.; Cohen, M.D.; Prophete, C.; Horton, L.; Sisco, M.; Park, S.-H.; Lee, H.-W.; et al. Prostate cancer in World Trade Center responders demonstrates evidence of an inflammatory cascade. Mol. Cancer Res. 2019, 17, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bover Manderski, M.T.; Black, K.; Udasin, I.G.; Giuliano, A.R.; Steinberg, M.B.; Ohman Strickland, P.; Black, T.M.; Dasaro, C.R.; Crane, M.; Harrison, D.; et al. Risk factors for head and neck cancer in the World Trade Center Health Program General Responder Cohort: Results from a nested case-control study. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 76, 854–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinman, E.J.; Christos, P.J.; Gerber, L.M.; Reilly, J.P.; Moran, W.F.; Einstein, A.J.; Neugut, A.I. NYPD cancer incidence rates 1995–2014 encompassing the entire World Trade Center cohort. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2015, 57, e101–e113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Zeig-Owens, R.; Moir, W.; Hall, C.B.; Schwartz, T.; Vossbrinck, M.; Jaber, N.; Webber, M.P.; Kelly, K.J.; Ortiz, V.; et al. Estimation of future cancer burden among rescue and recovery workers exposed to the World Trade Center disaster. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 828–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuminello, S.; van Gerwen, M.A.G.; Genden, E.; Crane, M.; Lieberman-Cribbin, W.; Taioli, E. Increased incidence of thyroid cancer among World Trade Center first responders: A descriptive epidemiological assessment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gerwen, M.A.G.; Tuminello, S.; Riggins, G.J.; Mendes, T.B.; Donovan, M.; Benn, E.K.T.; Genden, E.; Cerutti, J.M.; Taioli, E. Molecular study of thyroid cancer in World Trade Center responders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moline, J.M.; Herbert, R.; Crowley, L.; Troy, K.; Hodgman, E.; Shukla, G.; Udasin, I.; Luft, B.; Wallenstein, S.; Landrigan, P.; et al. Multiple myeloma in World Trade Center responders: A case series. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2009, 51, 896–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritikos, M.; Clouston, S.A.P.; Diminich, E.D.; Deri, Y.; Yang, X.; Carr, M.; Gandy, S.; Sano, M.; Bromet, E.J.; Luft, B.J. Pathway analysis for plasma β-amyloid, tau and neurofilament light (ATN) in World Trade Center responders at midlife. Neurol. Ther. 2020, 9, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landgren, O.; Zeig-Owens, R.; Giricz, O.; Goldfarb, D.; Murata, K.; Thoren, K.; Ramanathan, L.; Hultcrantz, M.; Dogan, A.; Nwankwo, G.; et al. Multiple myeloma and its precursor disease among firefighters exposed to the World Trade Center disaster. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colbeth, H.L.; Genere, N.; Hall, C.B.; Jaber, N.; Brito, J.P.; El Kawkgi, O.M.; Goldfarb, D.G.; Webber, M.P.; Schwartz, T.M.; Prezant, D.J.; et al. Evaluation of medical surveillance and incidence of post-11 September 2001, thyroid cancer in World Trade Center-exposed firefighters and emergency medical service workers. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 888–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.; Li, L.; Thakur, C.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yi, Z.; Chen, F. Proteomic characterization of the World Trade Center dust-activated mdig and c-myc signaling circuit linked to multiple myeloma. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clouston, S.A.P.; Kuan, P.; Kotov, R.; Mukherjee, S.; Thompson-Carino, P.; Bromet, E.J.; Luft, B.J. Risk factors for incident prostate cancer in a cohort of world trade center responders. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, C.R.; Wallenstein, S.; Shapiro, M.; Hashim, D.; Moline, J.M.; Udasin, I.; Crane, M.A.; Luft, B.J.; Lucchini, R.G.; Holden, W.L. Mortality among World Trade Center rescue and recovery workers, 2002–2011. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2016, 59, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffetta, P.; Zeig-Owens, R.; Wallenstein, S.; Li, J.; Brackbill, R.; Cone, J.; Farfel, M.; Holden, W.; Lucchini, R.; Webber, M.P.; et al. Cancer in World Trade Center responders: Findings from multiple cohorts and options for future study. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2016, 59, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szema, A.M. Cancer risk post 9/11. In World Trade Center Pulmonary Diseases and Multi-Organ System Manifestations; Szema, A.M., Ed.; Springer International: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ginevan, M.E.; Watkins, D.K. Logarithmic dose transformation in epidemiologic dose-response analysis: Use with caution. Regul. Toxicol. Pharm. 2010, 58, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederman, S.A.; Jones, R.L.; Caldwell, K.L.; Rauh, V.; Sheets, S.E.; Tang, D.; Viswanathan, S.; Becker, M.; Stein, J.L.; Wang, R.Y.; et al. Relation between cord blood mercury levels and early child development in a World Trade Center cohort. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008, 116, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, F.P.; Tang, D.; Rauh, V.; Lester, K.; Tsai, W.Y.; Tu, Y.H.; Weiss, L.; Hoepner, L.; King, J.; Del Priore, G.; et al. Relationships among polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-DNA adducts, proximity to the World Trade Center, and effects on fetal growth. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 1062–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Perera, F.; Tang, D.; Whyatt, R.; Lederman, S.A.; Jedrychowski, W. DNA damage from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons measured by benzo[a]pyrene-DNA adducts in mothers and newborns from Northern Manhattan, the World Trade Center Area, Poland, and China. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2005, 14, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, F.P.; Tang, D.; Rauh, V.; Tu, Y.H.; Tsai, W.Y.; Becker, M.; Stein, J.L.; King, J.; Del Priore, G.; Lederman, S.A. Relationship between polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-DNA adducts, environmental tobacco smoke, and child development in the World Trade Center cohort. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 1497–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spratlen, M.J.; Perera, F.P.; Lederman, S.A.; Robinson, M.; Kannan, K.; Trasande, L.; Herbstman, J. Cord blood perfluoroalkyl substances in mothers exposed to the World Trade Center disaster during pregnancy. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 246, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spratlen, M.J.; Perera, F.P.; Lederman, S.A.; Robinson, M.; Kannan, K.; Herbstman, J.; Trasande, L. The association between perfluoroalkyl substances and lipids in cord blood. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spratlen, M.J.; Perera, F.P.; Lederman, S.A.; Rauh, V.A.; Robinson, M.; Kannan, K.; Trasande, L.; Herbstman, J. The association between prenatal exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances and childhood neurodevelopment. Environ. Pollut 2020, 263, 114444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbstman, J.B.; Sjodin, A.; Kurzon, M.; Lederman, S.A.; Jones, R.S.; Rauh, V.; Needham, L.L.; Tang, D.; Niedzwiecki, M.; Wang, R.Y.; et al. Prenatal exposure to PBDEs and neurodevelopment. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010, 118, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowell, W.J.; Lederman, S.A.; Sjodin, A.; Jones, R.; Wang, S.; Perera, F.P.; Wang, R.; Rauh, V.A.; Herbstman, J.B. Prenatal exposure to polybrominated diphenyl ethers and child attention problems at 3–7 years. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2015, 52, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lederman, S.A.; Rauh, V.; Weiss, L.; Stein, J.L.; Hoepner, L.A.; Becker, M.; Perera, F.P. The effects of the World Trade Center event on birth outcomes among term deliveries at three lower Manhattan hospitals. Environ. Health Perspect. 2004, 112, 1772–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaylord, A.; Berger, K.I.; Naidu, M.; Attina, T.M.; Gilbert, J.; Koshy, T.T.; Han, X.; Marmor, M.; Shao, Y.; Giusti, R.; et al. Serum perfluoroalkyl substances and lung function in adolescents exposed to the World Trade Center disaster. Environ. Res. 2019, 172, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trasande, L.; Fiorino, E.K.; Attina, T.; Berger, K.; Goldring, R.; Chemtob, C.; Levy-Carrick, N.; Shao, Y.; Liu, M.; Urbina, E.; et al. Associations of World Trade Center exposures with pulmonary and cardiometabolic outcomes among children seeking care for health concerns. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 444, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshy, T.T.; Attina, T.M.; Ghassabian, A.; Gilbert, J.; Burdine, L.K.; Marmor, M.; Honda, M.; Chu, D.B.; Han, X.; Shao, Y.; et al. Serum perfluoroalkyl substances and cardiometabolic consequences in adolescents exposed to the World Trade Center disaster and a matched comparison group. Environ. Int. 2017, 109, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, C.R.; Savitz, D.A.; Bellinger, D.C. Perfluorooctanoate and neuropsychological outcomes in children. Epidemiology 2013, 24, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Rogan, W.J.; Chen, H.-Y.; Chen, P.-C.; Su, P.-H.; Chen, H.-Y.; Wang, S.-L. Prenatal exposure to perfluroalkyl substances and children’s IQ: The Taiwan maternal and infant cohort study. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2015, 218, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goudarzi, H.; Nakajima, S.; Ikeno, T.; Sasaki, S.; Kobayashi, S.; Miyashita, C.; Ito, S.; Araki, A.; Nakazawa, H.; Kishi, R. Prenatal exposure to perfluorinated chemicals and neurodevelopment in early infancy: The Hokkaido Study. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 541, 1002–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeddy, Z.; Hartman, T.J.; Taylor, E.V.; Poteete, C.; Kordas, K. Prenatal concentrations of Perfluoroalkyl substances and early communication development in British girls. Early Hum. Dev. 2017, 109, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.H.; Oken, E.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Calafat, A.M.; Ye, X.; Bellinger, D.C.; Webster, T.F.; White, R.F.; Sagiv, S.K. Prenatal and childhood exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and child cognition. Environ. Int. 2018, 115, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liew, Z.; Ritz, B.; Bach, C.C.; Asarnow, R.F.; Bech, B.H.; Nohr, E.A.; Bossi, R.; Henriksen, T.B.; Bonefeld-Jørgensen, E.C.; Olsen, J. Prenatal exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances and IQ scores at age 5; a study in the Danish National Birth Cohort. Environ. Health Perspect. 2018, 126, 067004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, A.M.; Yolton, K.; Xie, C.; Dietrich, K.N.; Braun, J.M.; Webster, G.M.; Calafat, A.M.; Lanphear, B.P.; Chen, A. Prenatal and childhood exposure to poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and cognitive development in children at age 8 years. Environ. Res. 2019, 172, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trasande, L.; Koshy, T.T.; Gilbert, J.; Burdine, L.K.; Marmor, M.; Han, X.; Shao, Y.; Chemtob, C.; Attina, T.M.; Urbina, E.M. Cardiometabolic profiles of adolescents and young adults exposed to the World Trade Center Disaster. Environ. Res. 2017, 160, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trye, A.; Berger, K.I.; Naidu, M.; Attina, T.M.; Gilbert, J.; Koshy, T.T.; Han, X.; Marmor, M.; Shao, Y.; Giusti, R.; et al. Respiratory health and lung function in children exposed to the World Trade Center disaster. J. Pediatr. 2018, 201, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargano, L.M.; Thomas, P.A.; Stellman, S.D. Asthma control in adolescents 10 to 11 y after exposure to the World Trade Center disaster. Pediatr. Res. 2017, 81, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, L.G.; Han, X.; Koshy, T.T.; Shao, Y.; Chu, D.B.; Kannan, K.; Trasande, L. Adolescents exposed to the World Trade Center collapse have elevated serum dioxin and furan concentrations more than 12 years later. Environ. Int. 2018, 111, 267–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayne, S.; Ikonomou, M.G.; Butt, C.M.; Diamond, M.L.; Truong, J. Polychlorinated dioxins and furans from the World Trade Center attacks in exterior window films from lower Manhattan in New York City. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 1995–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litten, S.; McChesney, D.J.; Hamilton, M.C.; Fowler, B. Destruction of the World Trade Center and PCBs, PBDEs, PCDD/Fs, PBDD/Fs, and chlorinated biphenylenes in water, sediment, and sewage sludge. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 5502–5510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edelman, P.; Osterloh, J.; Pirkle, J.; Caudill, S.P.; Grainger, J.; Jones, R.; Blount, B.; Calafat, A.; Turner, W.; Feldman, D.; et al. Biomonitoring of chemical exposure among New York City firefighters responding to the World Trade Center fire and collapse. Environ. Health Perspect. 2003, 111, 1906–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malin, A.M.; Fowers, B.J. Adolescents’ reactions to the World Trade Center destruction: A study of political trauma in metropolitan New York. Curr. Psychol. 2004, 23, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, S. “A war that had come right to them”: Group work with traumatized adolescents following September 11. Int. J. Group Psychother. 2005, 55, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, L. Marking the anniversary: Adolescents and the September 11 healing process. Int. J. Group Psychother. 2005, 55, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; Stuber, J.; Galea, S.; Fairbrother, G. Panic reactions to terrorist attacks and probable posttraumatic stress disorder in adolescents. J. Trauma Stress 2006, 19, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demaria, T.; Barrett, M.; Kerasiotis, B.; Rohlih, J.; Chemtob, C. Bio-psycho-social assessment of 9/11-bereaved children. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1071, 481–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guffanti, G.; Geronazzo-Alman, L.; Fan, B.; Duarte, C.S.; Musa, G.J.; Hoven, C.W. Homogeneity of severe posttraumatic stress disorder symptom profiles in children and adolescents across gender, age, and traumatic experiences related to 9/11. J. Trauma Stress 2016, 29, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geronazzo-Alman, L.; Guffanti, G.; Eisenberg, R.; Fan, B.; Musa, G.J.; Wicks, J.; Bresnahan, M.; Duarte, C.S.; Hoven, C. Comorbidity classes and associated impairment, demographics and 9/11-exposures in 8236 children and adolescents. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2017, 96, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geronazzo-Alman, L.; Fan, B.; Duarte, C.S.; Layne, C.M.; Wicks, J.; Guffanti, G.; Musa, G.J.; Hoven, C.W. The distinctiveness of grief, depression, and posttraumatic stress: Lessons from children after 9/11. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 58, 971–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoven, C.W.; Duarte, C.S.; Mandell, D.J. Children’s mental health after disasters: The impact of the World Trade Center attack. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2003, 5, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoven, C.W.; Duarte, C.S.; Wu, P.; Erickson, E.A.; Musa, G.J.; Mandell, D.J. Exposure to trauma and separation anxiety in children after the WTC attack. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2004, 8, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoven, C.W.; Duarte, C.S.; Lucas, C.P.; Wu, P.; Mandell, D.J.; Goodwin, R.D.; Cohen, M.; Balaban, V.; Woodruff, B.A.; Bin, F.; et al. Psychopathology among New York city public school children 6 months after September 11. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, C.S.; Hoven, C.W.; Wu, P.; Bin, F.; Cotel, S.; Mandell, D.J.; Nagasawa, M.; Balaban, V.; Wernikoff, L.; Markenson, D. Posttraumatic stress in children with first responders in their families. J. Trauma Stress 2006, 19, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comer, J.S.; Fan, B.; Duarte, C.S.; Wu, P.; Musa, G.J.; Mandell, D.J.; Albano, A.M.; Hoven, C.W. Attack-related life disruption and child psychopathology in New York City public schoolchildren 6-months post-9/11. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2010, 39, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, C.S.; Eisenberg, R.; Musa, G.J.; Addolorato, A.; Shen, S.; Hoven, C.W. Children’s Knowledge about Parental Exposure to Trauma. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2019, 12, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.S.; Wu, P.; Cheung, A.; Mandell, D.J.; Fan, B.; Wicks, J.; Musa, G.J.; Hoven, C.W. Media use by children and adolescents from New York City 6 months after the WTC attack. J. Trauma Stress 2011, 24, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemtob, C.M.; Nomura, Y.; Josephson, L.; Adams, R.E.; Sederer, L. Substance use and functional impairment among adolescents directly exposed to the 2001 World Trade Center attacks. Disasters 2009, 33, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargano, L.M.; Welch, A.E.; Stellman, S.D. Substance use in adolescents 10 years after the World Trade Center attacks in New York City. J. Child Adolesc. Subst. Abus. 2016, 26, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koplewicz, H.S.; Cloitre, M.; Reyes, K.; Kessler, L.S. The 9/11 experience: Who’s listening to the children? Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2004, 27, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, P.A.; Brackbill, R.; Thalji, L.; DiGrande, L.; Campolucci, S.; Thorpe, L.; Henning, K. Respiratory and other health effects reported in children exposed to the World Trade Center disaster of 11 September 2001. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008, 116, 1383–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, G.S.; Stroehla, B.C. The epidemiology of autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun. Rev. 2003, 2, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, S.J.; Rau, L.M. Autoimmune diseases: A leading cause of death among young and middle-aged women in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2000, 90, 1463–1466. [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Archie, S.A.; Izmirly, P.M.; Berman, J.R.; Brite, J.; Walker, D.J.; Dasilva, R.C.; Petrsoric, L.J.; Cone, J.E. Systemic autoimmune disease among adults exposed to the 11 September 2001, terrorist attack. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020, 72, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, M.P.; Moir, W.; Crowson, C.S.; Cohen, H.W.; Zeig-Owens, R.; Hall, C.B.; Berman, J.; Qayyum, B.; Jaber, N.; Matteson, E.L.; et al. Post-11 September 2001, incidence of systemic autoimmune diseases in World Trade Center-exposed firefighters and emergency medical service workers. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2016, 91, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, M.P.; Moir, W.; Zeig-Owens, R.; Glaser, M.S.; Jaber, N.; Hall, C.; Berman, J.; Qayyum, B.; Loupasakis, K.; Kelly, K.; et al. Nested case-control study of selected systemic autoimmune diseases in World Trade Center rescue/recovery workers. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015, 67, 1369–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscarino, J.A.; Forsberg, C.W.; Goldberg, J. A twin study of the association between PTSD symptoms and rheumatoid arthritis. Psychosom. Med. 2010, 72, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, A.; Cohen, B.E.; Seal, K.H.; Bertenthal, D.; Margaretten, M.; Nishimi, K.; Neylan, T.C. Elevated risk for autoimmune disorders in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2015, 77, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bookwalter, D.B.; Roenfeldt, K.A.; Leardmann, C.A.; Kong, S.Y.; Riddle, M.S.; Rull, R.P. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of selected autoimmune diseases among US military personnel. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, A.L.; Kubzansky, L.D.; Malspeis, S.; Feldman, C.H.; Costenbader, K.H. Association of depression with risk of incident systemic lupus erythematosus in women assessed across 2 decades. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 1271–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.C.; Agnew-Blais, J.; Malspeis, S.; Keyes, K.; Costenbader, K.; Kubzansky, L.D.; Roberts, A.L.; Koenen, K.C.; Karlson, E.W. Post-traumatic stress disorder and risk for incident rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2016, 68, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brook, R.D.; Rajagopalan, S.; Pope, C.A.; Brook, J.R.; Bhatnagar, A.; Diez-Roux, A.V.; Holguin, F.; Hong, Y.; Luepker, R.V.; Mittleman, M.A.; et al. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: An update to the scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation 2010, 121, 2331–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotman, D.J.; Golden, S.H.; Wittstein, I.S. The cardiovascular toll of stress. Lancet 2007, 370, 1089–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtman, J.H.; Bigger, J.T., Jr.; Blumenthal, J.A.; Frasure-Smith, N.; Kaufmann, P.G.; Lespérance, F.; Mark, D.B.; Sheps, D.S.; Taylor, C.B.; Froelicher, E.S. Depression and coronary heart disease: Recommendations for screening, referral, and treatment—A science advisory from the American Heart Association Prevention Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Circulation 2008, 118, 1768–1775. [Google Scholar]

- Yousuf, T.; Nakhle, A.; Rawal, H.; Harrison, D.; Maini, R.; Irimpen, A. Natural disasters and acute myocardial infarction. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 63, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, H.W.; Zeig-Owens, R.; Joe, C.; Hall, C.B.; Webber, M.P.; Weiden, M.D.; Cleven, K.L.; Jaber, N.; Skerker, M.; Yip, J.; et al. Long-term cardiovascular disease risk among firefighters after the World Trade Center disaster. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e199775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, H.T.; Miller-Archie, S.A.; Cone, J.E.; Morabia, A.; Stellman, S.D. Heart disease among adults exposed to the 11 September 2001 World Trade Center disaster: Results from the World Trade Center Health Registry. Prev. Med. 2011, 53, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remch, M.; Laskaris, Z.; Flory, J.; Mora-McLaughlin, C.; Morabia, A. Post-traumatic stress disorder and cardiovascular diseases: A cohort study of men and women involved in cleaning the debris of the World Trade Center Complex. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2018, 11, e004572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brackbill, R.M.; Thorpe, L.E.; DiGrande, L.; Perrin, M.; Sapp, J.H., 2nd; Wu, D.; Campolucci, S.; Walker, D.J.; Cone, J.; Pulliam, P.; et al. Surveillance for World Trade Center disaster health effects among survivors of collapsed and damaged buildings. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2006, 55, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brackbill, R.M.; Cone, J.E.; Farfel, M.R.; Stellman, S.D. Chronic physical health consequences of being injured during the terrorist attacks on World Trade Center on 11 September 2001. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 179, 1076–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, H.T.; Stellman, S.D.; Morabia, A.; Miller-Archie, S.A.; Alper, H.; Laskaris, Z.; Brackbill, R.M.; Cone, J.E. Cardiovascular disease hospitalizations in relation to exposure to the 11 September 2001 World Trade Center disaster and posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2013, 2, e000431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alper, H.E.; Yu, S.; Stellman, S.D.; Brackbill, R.M. Injury, intense dust exposure, and chronic disease among survivors of the World Trade Center terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001. Inj. Epidemiol. 2017, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Alper, H.E.; Nguyen, A.M.; Brackbill, R.M. Risk of stroke among survivors of the 11 September 2001 World Trade Center disaster. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 60, e371–e376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Zeig-Owens, R.; Hall, C.B.; Liu, Y.; Rabin, L.; Schwartz, T.; Webber, M.P.; Appel, D.; Prezant, D.J. World Trade Center exposure, post-traumatic stress disorder, and subjective cognitive concerns in a cohort of rescue/recovery workers. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2020, 141, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clouston, S.; Pietrzak, R.H.; Kotov, R.; Richards, M.; Spiro, A.; Scott, S.; Deri, Y.; Mukherjee, S.; Stewart, C.; Bromet, E.; et al. Traumatic exposures, posttraumatic stress disorder, and cognitive functioning in World Trade Center responders. Alzheimers Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2017, 3, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clouston, S.A.P.; Deri, Y.; Diminich, E.; Kew, R.; Kotov, R.; Stewart, C.; Yang, X.; Gandy, S.; Sano, M.; Bromet, E.J.; et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and total amyloid burden and amyloid-β 42/40 ratios in plasma: Results from a pilot study of World Trade Center responders. Alzheimer’s Dement. Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2019, 11, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clouston, S.A.; Kotov, R.; Pietrzak, R.H.; Luft, B.J.; Gonzalez, A.; Richards, M.; Ruggero, C.J.; Spiro, A., 3rd; Bromet, E.J. Cognitive impairment among World Trade Center responders: Long-term implications of re-experiencing the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Alzheimers Dement. (Amst.) 2016, 4, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuitevoerder, S.; Rosen, J.W.; Twamley, E.W.; Ayers, C.R.; Sones, H.; Lohr, J.B.; Goetter, E.M.; Fonzo, G.A.; Holloway, K.J.; Thorp, S.R. A meta-analysis of cognitive functioning in older adults with PTSD. J. Anxiety Disord. 2013, 27, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, D.P.; Friedl, K.E.; Weiner, M.W. Military risk factors for cognitive decline, dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2013, 10, 907–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clouston, S.A.P.; Diminich, E.D.; Kotov, R.; Pietrzak, R.H.; Richards, M.; Spiro, A., 3rd; Deri, Y.; Carr, M.; Yang, X.; Gandy, S.; et al. Incidence of mild cognitive impairment in World Trade Center responders: Long-term consequences of re-experiencing the events on 9/11/2001. Alzheimers Dement. (Amst.) 2019, 11, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganzel, B.L.; Kim, P.; Glover, G.H.; Temple, E. Resilience after 9/11: Multimodal neuroimaging evidence for stress-related change in the healthy adult brain. Neuroimage 2008, 40, 788–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clouston, S.A.P.; Guralnik, J.M.; Kotov, R.; Bromet, E.J.; Luft, B.J. Functional limitations among responders to the World Trade Center attacks 14 years after the disaster: Implications of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Trauma Stress 2017, 30, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Clouston, S.; Kotov, R.; Bromet, E.; Luft, B. Handgrip strength of World Trade Center (WTC) responders: The role of re-experiencing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuan, P.-F.; Waszczuk, M.A.; Kotov, R.; Clouston, S.; Yang, X.; Singh, P.K.; Glenn, S.T.; Gomez, E.C.; Wang, J.; Bromet, E. Gene expression associated with PTSD in World Trade Center responders: An RNA sequencing study. Transl. Psychiatry 2017, 7, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuan, P.-F.; Yang, X.; Clouston, S.; Ren, X.; Kotov, R.; Waszczuk, M.; Singh, P.K.; Glenn, S.T.; Gomez, E.C.; Wang, J. Cell type-specific gene expression patterns associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in World Trade Center responders. Transl. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, M.L.; Calderón-Garcidueñas, L. Air pollution: Mechanisms of neuroinflammation and CNS disease. Trends Neurosci. 2009, 32, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon-Garciduenas, L.; Solt, A.C.; Henriquez-Roldan, C.; Torres-Jardon, R.; Nuse, B.; Herritt, L.; Villarreal-Calderon, R.; Osnaya, N.; Stone, I.; Garcia, R.; et al. Long-term air pollution exposure is associated with neuroinflammation, an altered innate immune response, disruption of the blood-brain barrier, ultrafine particulate deposition, and accumulation of amyloid beta-42 and alpha-synuclein in children and young adults. Toxicol. Pathol. 2008, 36, 289–310. [Google Scholar]

- Weuve, J.; Puett, R.C.; Schwartz, J.; Yanosky, J.D.; Laden, F.; Grodstein, F. Exposure to particulate air pollution and cognitive decline in older women. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012, 172, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Garcidueñas, L.; Mora-Tiscareño, A.; Ontiveros, E.; Gómez-Garza, G.; Barragán-Mejía, G.; Broadway, J.; Chapman, S.; Valencia-Salazar, G.; Jewells, V.; Maronpot, R.R.; et al. Air pollution, cognitive deficits and brain abnormalities: A pilot study with children and dogs. Brain Cogn. 2008, 68, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.C.; Schwartz, J. Neurobehavioral effects of ambient air pollution on cognitive performance in US adults. Neurotoxicology 2009, 30, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonne, C.; Elbaz, A.; Beevers, S.; Singh-Manoux, A. Traffic-related air pollution in relation to cognitive function in older adults. Epidemiology 2014, 25, 674–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shou, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, D.; Yin, H.; Shi, Y.; Chen, M.; Lu, L.; Qian, Q.; Zhao, D.; Hu, Y.; et al. Ambient PM2.5 chronic exposure leads to cognitive decline in mice: From pulmonary to neuronal inflammation. Toxicol. Lett. 2020, 331, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, T.E.; Davis, D.A.; Iwata, N.; Tanner, J.A.; Snyder, D.; Ning, Z.; Kam, W.; Hsu, Y.T.; Winkler, J.W.; Chen, J.C.; et al. Glutamatergic neurons in rodent models respond to nanoscale particulate urban air pollutants in vivo and in vitro. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | FDNY Responder Cohort | General Responder Cohort | NYC Survivor Cohort | Registry (as of 4 August 2020) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number enrolled | 15,328 | 43,811 | 13,569 | 65,717 |

| Percent deceased | 3.2 | 2.9 | 2.1 | 8.0 † |

| Percent male | 97 | 86 | 50 | 60 |

| Percent Caucasian | 87 | 78 | 40 | 63 |

| Mean age on 9/11 (years) | 39.8 | 38.6 | 42.2 | 39.1 |

| Percent aged 65+ | 20 | 17 | 53 | 31 |

| Subpopulation | Solicitation and Award (U01 Only) | Funding (millions) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. Applications | No. Funded (%) † | Awarded Amount | Other Source ‡ | Total (%) | |

| Responders only | 183 | 56 (30.6) | 83.6 | 10.0 | 93.6 (73.5) |

| Responders & survivors | 19 | 2 (10.5) | 1.5 | 0 | 1.5 (1.2) |

| Survivors excl. WTC youth | 23 | 4 (17.4) | 5.4 | 1.5 | 6.9 (5.4) |

| WTC youth only | 28 | 9 (32.1) | 18.2 | 0 | 18.2 (14.3) |

| Other § | 13 | 4 (30.8) | 4.5 | 2.7 | 7.2 (5.7) |

| Totals: | 266 | 75 (28.2) | 113.2 | 14.2 | 127.4 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santiago-Colón, A.; Daniels, R.; Reissman, D.; Anderson, K.; Calvert, G.; Caplan, A.; Carreón, T.; Katruska, A.; Kubale, T.; Liu, R.; et al. World Trade Center Health Program: First Decade of Research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7290. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197290

Santiago-Colón A, Daniels R, Reissman D, Anderson K, Calvert G, Caplan A, Carreón T, Katruska A, Kubale T, Liu R, et al. World Trade Center Health Program: First Decade of Research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(19):7290. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197290

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantiago-Colón, Albeliz, Robert Daniels, Dori Reissman, Kristi Anderson, Geoffrey Calvert, Alexis Caplan, Tania Carreón, Alan Katruska, Travis Kubale, Ruiling Liu, and et al. 2020. "World Trade Center Health Program: First Decade of Research" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 19: 7290. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197290

APA StyleSantiago-Colón, A., Daniels, R., Reissman, D., Anderson, K., Calvert, G., Caplan, A., Carreón, T., Katruska, A., Kubale, T., Liu, R., Nembhard, R., Robison, W. A., Yiin, J., & Howard, J. (2020). World Trade Center Health Program: First Decade of Research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 7290. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197290