Prevalence, Determinants, and Effects of Food Insecurity among Middle Eastern and North African Migrants and Refugees in High-Income Countries: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources

2.3. Search Strategy

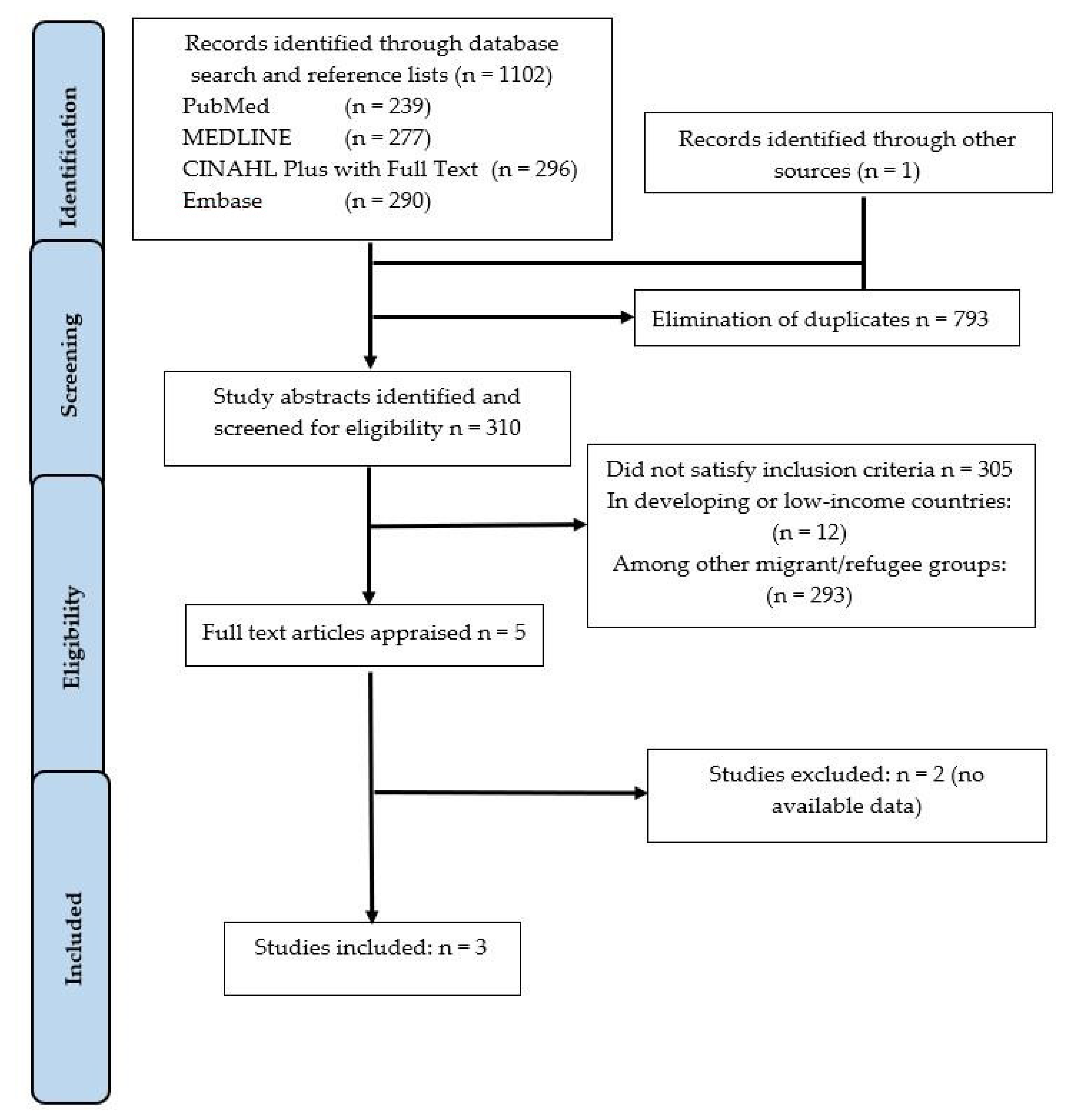

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Collection Process and Data Items

2.6. Assessment of Methodological Quality

3. Results

3.1. Methodological Quality

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Prevalence of Food Insecurity

3.4. Determinants Associated with Food Insecurity

3.5. Effects of Food Insecurity

4. Discussion

5. Recommendations for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Section/Topic | Item no. | Checklist Item | Reported on Page no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review, meta-analysis, or both. | 1 |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary including, as applicable: background; objectives; data sources; study eligibility criteria, participants, and interventions; study appraisal and synthesis methods; results; limitations; conclusions and implications of key findings; systematic review registration number. | 1 |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. | 2, 3 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of questions being addressed with reference to participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design (PICOS). | 3 |

| METHODS | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate if a review protocol exists, if and where it can be accessed (e.g., Web address), and, if available, provide registration information including registration number. | NA |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify study characteristics (e.g., PICOS, length of follow-up) and report characteristics (e.g., years considered, language, publication status) used as criteria for eligibility, giving rationale. | 3 |

| Information sources | 7 | Describe all information sources (e.g., databases with dates of coverage, contact with study authors to identify additional studies) in the search and date last searched. | 3 |

| Search | 8 | Present full electronic search strategy for at least one database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | 3 |

| Study selection | 9 | State the process for selecting studies (i.e., screening, eligibility, included in systematic review, and, if applicable, included in the meta-analysis). | 4 |

| Data collection process | 10 | Describe method of data extraction from reports (e.g., piloted forms, independently, in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | 4 |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought (e.g., PICOS, funding sources) and any assumptions and simplifications made. | 3 |

| Risk of bias in individual studies | 12 | Describe methods used for assessing risk of bias of individual studies (including specification of whether this was done at the study or outcome level), and how this information is to be used in any data synthesis. | N/A (Cross Sectional) |

| Summary measures | 13 | State the principal summary measures (e.g., risk ratio, difference in means). | 4 |

| Synthesis of results | 14 | Describe the methods of handling data and combining results of studies, if done, including measures of consistency (e.g., I2) for each meta-analysis. | 4 |

| Risk of bias across studies | 15 | Specify any assessment of risk of bias that may affect the cumulative evidence (e.g., publication bias, selective reporting within studies). | N/A (Cross Sectional) |

| Additional analyses | 16 | Describe methods of additional analyses (e.g., sensitivity or subgroup analyses, meta-regression), if done, indicating which were pre-specified. | N/A |

| RESULTS | |||

| Study selection | 17 | Give numbers of studies screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally with a flow diagram. | 6 |

| Study characteristics | 18 | For each study, present characteristics for which data were extracted (e.g., study size, PICOS, follow-up period) and provide the citations. | 6 |

| Risk of bias within studies | 19 | Present data on risk of bias of each study and, if available, any outcome level assessment (see item 12). | N/A |

| Results of individual studies | 20 | For all outcomes considered (benefits or harms), present, for each study: (a) simple summary data for each intervention group (b) effect estimates and confidence intervals, ideally with a forest plot. | 9 |

| Synthesis of results | 21 | Present results of each meta-analysis done, including confidence intervals and measures of consistency. | 7, 8 |

| Risk of bias across studies | 22 | Present results of any assessment of risk of bias across studies (see Item 15). | N/A |

| Additional analysis | 23 | Give results of additional analyses, if done (e.g., sensitivity or subgroup analyses, meta-regression [see Item 16]). | N/A |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Summary of evidence | 24 | Summarize the main findings including the strength of evidence for each main outcome; consider their relevance to key groups (e.g., healthcare providers, users, and policy makers). | 12 |

| Limitations | 25 | Discuss limitations at study and outcome level (e.g., risk of bias), and at review-level (e.g., incomplete retrieval of identified research, reporting bias). | 12 |

| Conclusions | 26 | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence, and implications for future research. | 13 |

| FUNDING | |||

| Funding | 27 | Describe sources of funding for the systematic review and other support (e.g., supply of data); role of funders for the systematic review. | 13 |

Appendix B

| S | MeSH Terms | Output |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | (MH “Food Security”) OR “food security” | 4253 |

| S2 | (“MH Food insecurity”) OR “food insecurity” | 3641 |

| S3 | (MH “Food Preferences”) | 6201 |

| S4 | “Food access” OR “Food accessibility” | 431 |

| S5 | “Food stability” | 89 |

| S6 | “Food availability” | 1556 |

| S7 | (MH “Refugees”) OR “refugees” | 8208 |

| S8 | “displaced persons” OR “resettled” | 5862 |

| S9 | (MH “Immigrants”) OR “immigrants” OR migrant | 24,601 |

| S10 | S1 OR S2 | 5287 |

| S11 | S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 | 8041 |

| S12 | S7 OR S8 OR S9 | 31,601 |

| S13 | S10 OR S11 | 12,888 |

| S14 | S12 AND S13 | 296 |

Appendix C

| Author(s) and Year (Reference Number) | Title | Reasons for Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Bertmann et al. 2016 | A Pilot Study of Food Security among Syrian Refugees in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. | Not enough data available |

| Ebadi et al. 2017 | Food Security and International Migration: A comparative study of Asia, Middle East/North Africa, Latin America/Caribbean and Sub-Saharan Africa. | Not enough data available |

Appendix D

| JBI Critical Appraisal | Dharod & Clark, 2013 [29] | Anderson et al. (2014) [13] | Alasagheirin et al., 2018 [30] | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined? | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Were objective, standard criteria used for measurement of the condition? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Three different tools were used to measure food security (see Discussion above) |

| Were confounding factors identified? | Yes | Unclear | No | |

| Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | No | No | No | |

| Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? | Yes | No | Yes | The use of different tools and sampling methods and sample size resulted in different levels of reliability, generalizability. |

| Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | Yes | Yes | Yes |

References

- Substantive Issues Arising in the Implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: General Comment No. 12 (20th sess.): The Right to Adequate Food (art. 11), UN Doc. E/C.12/1999/5, 12 May 1999. Available online: https://www.globalhealthrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/CESCR-General-Comment-No.-12-The-Right-to-Adequate-Food.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2019).

- The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2017. Building Resilience for Peace and Food Security. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/a-I7695e.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2019).

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations, New York 2017. ST/ESA/SER.A/404. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/publications/migrationreport/docs/MigrationReport2017_Highlights.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2019).

- International Migration 2019: Wall Chart. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/publications/wallchart/docs/MigrationStock2019_Wallchart.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2019).

- Rosier, K. Food insecurity in Australia: What is it, who experiences it and how can child and family services support families experiencing it? J. Home Econ. Inst. Aust. 2012, 19, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lawlis, T.; Islam, W.; Upton, P. Achieving the four dimensions of food security for resettled refugees in Australia: A systematic review. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 75, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavami, S.M. Food Insecurity and Culture: A Study of Cambodian and Brazilian Immigrants. Master’s Thesis, University of Massachusetts, Boston, MA, USA, September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnlein, H.V. Gender roles, food system biodiversity, and food security in Indigenous Peoples’ communities. Matern. Child Nutr. 2017, 13, e12529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Initiative Commissioned by FAO and the International India Treaty Council. Available online: http://www.fao.org/tempref/docrep/fao/011/ak243e/ak243e00.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2019).

- White, H.; Kokotsaki, K. Indian food in the UK: Personal values and changing patterns of consumption. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2004, 28, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greder, K.; de Slowing, F.R.; Doudna, K. Latina immigrant mothers: Negotiating new food environments to preserve cultural food practices and healthy child eating. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2012, 41, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, M.; Laroche, M.; Pons, F.; Kastoun, R. Acculturation and consumption: Textures of cultural adaptation. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2009, 33, 196–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.; Hadzibegovic, D.S.; Moseley, J.M.; Sellen, D.W. Household food insecurity shows associations with food intake, social support utilization and dietary change among refugee adult caregivers resettled in the United States. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2014, 53, 312–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. Regional Surveys: Middle East and North Africa’ UNHCR Global Appeal 2018 2019 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees 2019. Available online: http://library.ifla.org/2409/1/s01-2018-obodoruku-en.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2020).

- Asbu, E.Z.; Masri, M.D.; Kaissi, A. Health status and health systems financing in the MENA region: Roadmap to universal health coverage. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2017, 2, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, J. Religion and Politics in Europe, the Middle East and North Africa; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Doocy, S.; Sirois, A.; Anderson, J.; Tileva, M.; Biermann, E.; Storey, J.D.; Burnham, G. Food security and humanitarian assistance among displaced Iraqi populations in Jordan and Syria. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghattas, H.; Sassine, A.J.; Seyfert, K.; Nord, M.; Sahyoun, N.R. Prevalence and correlates of food insecurity among Palestinian refugees in Lebanon: Data from a household survey. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baban, F.; Ilcan, S.; Rygiel, K. Syrian refugees in Turkey: Pathways to precarity, differential inclusion, and negotiated citizenship rights. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2017, 43, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfahani, F.; Kadiyala, S.; Ghattas, H. Food insecurity and subjective wellbeing among Arab youth living in varying contexts of political instability. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 64, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellen, D.W.; Tedstone, A.E.; Frize, J. Food insecurity among refugee families in East London: Results of a pilot assessment. Public Health Nutr. 2002, 5, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cordeiro, L.; Sibeko, L.; Nelson-Peterman, J. Healthful, Cultural foods and safety net use among Cambodian and Brazilian immigrant communities in Massachusetts. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2018, 20, 991–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnery, D.; Haldeman, L.; Morrison, S.D.; Dharod, J.M. Food insecurity and budgeting among Liberians in the US: How are they related to socio-demographic and pre-resettlement characteristics. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2015, 17, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahabi, M.; Damba, C. Perceived barriers in accessing food among recent Latin American immigrants in Toronto. Int. J. Equity Health 2013, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarraf, D.; Sanou, D.; Blanchet, R.; Nana, C.P.; Batal, M.; Giroux, I. Prevalence and determinants of food insecurity in migrant Sub-Saharan African and Caribbean households in Ottawa, Canada. Int. J. Migr. Health Soc. Care. 2018, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Reprint—Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Phys. Ther. 2009, 89, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, A.; Smith, D.; Booth, A. Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual. Health Res 2012, 22, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. (Eds.) Chapter 7: Systematic Reviews of Etiology and Risk. In Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual; 2017; Available online: https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Dharod, J.M.; Croom, J.E.; Sady, C.G. Food insecurity: Its relationship to dietary intake and body weight among Somali refugee women in the United States. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2013, 45, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasagheirin, M.H.; Clark, M.K. Skeletal growth, body composition, and metabolic risk among North Sudanese immigrant children. Public Health Nurs. 2018, 35, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKechnie, R.; Turrell, G.; Giskes, K.; Gallegos, D. Single-item measure of food insecurity used in the National Health Survey may underestimate prevalence in Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2018, 42, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guide to Measuring Household Food Security. USDA Food and Nutrition Service. Revised. 2000. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/guide-measuring-household-food-security-revised-2000 (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Wilde, P.; Nord, M. The effect of food stamps on food security: A panel data approach. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2005, 27, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, J.; Gupta, S.K.; Tran, P.; Cook, J.T.; Meyers, A.F. Hunger in legal immigrants in California, Texas, and Illinois. Am. J. Public Health 2000, 90, 1629–1633. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Seligman, H.K.; Laraia, B.A.; Kushel, M.B. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, M.S.; Peerson, J.; Love, B.; Achterberg, C.; Murphy, S.P. Food insecurity is positively related to overweight in women. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 1738–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlüssel, M.M.; Silva, A.A.M.; Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Kac, G. Household food insecurity and excess weight/obesity among Brazilian women and children: A life-course approach. Cad. Saude Publica 2013, 29, 219–226. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, T.; Gustafson, A.; Houlihan, J.; Davenport, C.; Kern, K.; Martin, N.; Hege, A. The obesity food insecurity paradox: Student focus group feedback to guide development of innovative curriculum. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, S71–S72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhurandhar, E.J. The food-insecurity obesity paradox: A resource scarcity hypothesis. Physiol. Behav. 2016, 162, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higginbottom, G.M.A.; Vallianatos, H.; Shankar, J.; Safipour, J.; Davey, C. Immigrant women’s food choices in pregnancy: Perspectives from women of Chinese origin in Canada. Ethn. Health. 2018, 23, 521–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanumihardjo, S.A.; Anderson, C.; Kaufer-Horwitz, M.; Bode, L.; Emenaker, N.J.; Haqq, A.M.; Satia, J.A.; Silver, H.J.; Stadler, D.D. Poverty, obesity, and malnutrition: An international perspective recognizing the paradox. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2007, 107, 1966–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, A.R.; Briefel, R.R.; Collins, A.M.; Rowe, G.M.; Klerman, J.A. Delivering summer electronic benefit transfers for children through the supplemental nutrition assistance program or the special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants, and children: Benefit use and impacts on food security and foods consumed. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libman, K. Food Insecurity and Health Disparities: Experiences from New York City. In Food Poverty and Insecurity: International Food Inequalities; Caraher, M., Coveney, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 55–65. [Google Scholar]

| SPIDER Tool | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| S | Middle Eastern or North African migrants or refugees residing in a high-income country |

| P and I | Studies investigating the status of food security and challenges related to migrant/refugee access to affordable foods that meet their cultural needs. |

| D | No specific study design |

| E | Views and experiences of the members of participant groups |

| R | Both qualitative and quantitative |

| Citation | Study Design | Study Findings | Conclusion | Source of Funding | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author(s)/Year | Participants/Eligibility | Sampling/Recruitment/Study Setting | Data Collection/Tool | Demographic/FS/FS Impacts | ||

| Dharod et al. 2013 [29] | Eligibility: Women resident of Lewiston, Maine (US); have at least 1 child and the main meal preparer of the household. Ethnicity/Nationality: Somali | Method: Cross-sectional/convenience sample Size: 195 Somali women Recruitment: using a snowball sampling method Study setting: Lewiston (Maine) | Ten-item Radimer/Cornell Hunger Scale (Questionnaire) | Food Insecure (n = 131) Food Secure (n = 64) 3 times more likely to be overweight or obese | Somali refugees experienced high levels of FIS upon resettlement. Poor dietary habits and the high overweight/obesity rate among insecure families call for future research in understanding what role family structure, cultural norms, and food preference play in predicting food security and dietary habits among Somali and overall African refugees in the US. | Not reported |

| Anderson et al. (2014) [13] | Eligibility: Each family had at least one child under 3, and at least one legally resettled Sudanese parent who had been resettled for at least 5 years. Ethnicity/Nationality: Sudanese refugee families | Method: Cross-sectional Size: 49 recently arrived refugees. Recruitment: recruited through voluntary resettlement agency (VOLAG) case lists, church and community groups, and word-of-mouth (snowball approach) Study setting: Metropolitan Atlanta, USA | 10-item modified version of the Radimer/Cornell hunger scale (Questionnaire) | 71% experienced some form of household food insecurity:12% reported child hunger FIS associated with more frequent consumption of some low-cost, traditional Sudanese foods. | Increasing severity of household FIS was associated with decreased consumption of high-cost, high-nutrient-density food items. | Emory University Research Committee, and the Office of University-Community Partnerships of Emory University provided financial and in-kind support for data collection. Analysis was funded by awards from the Canada Research Chairs program (DWS) and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (LA). |

| Alasagheirin and Clark, 2018 [30] | Eligibility: Families with children (5 and 18 years old) and had lived in the United States Ethnicity/Nationality: Northern Sudan, Muslim and spoke Arabic | Method: Cross- sectional study Size: 31 families, including 64 children, 31 boys, and 33 girls. Recruitment: Identified from a Sudanese Society’s directory of families and were first contacted by a community leader regarding participation. Study setting: Midwestern satellite town of the Atlanta conurbation | Two questions from the U.S. Household Food Security Survey Module (Questionnaire + bodily measurements and blood testing) | Food insecurity 40% of families 26.6% were overweight or obese | Sudanese children may have unique risks related to low bone mass low muscle mass, high percent body fat metabolic biomarkers, inactivity, and FIS potentially contributing to adult osteoporosis, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. | The Institute for Clinical and Translational Science at the University of Iowa (CTSA) program, grant UL1 TR000442. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mansour, R.; Liamputtong, P.; Arora, A. Prevalence, Determinants, and Effects of Food Insecurity among Middle Eastern and North African Migrants and Refugees in High-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7262. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197262

Mansour R, Liamputtong P, Arora A. Prevalence, Determinants, and Effects of Food Insecurity among Middle Eastern and North African Migrants and Refugees in High-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(19):7262. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197262

Chicago/Turabian StyleMansour, Reima, Pranee Liamputtong, and Amit Arora. 2020. "Prevalence, Determinants, and Effects of Food Insecurity among Middle Eastern and North African Migrants and Refugees in High-Income Countries: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 19: 7262. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197262

APA StyleMansour, R., Liamputtong, P., & Arora, A. (2020). Prevalence, Determinants, and Effects of Food Insecurity among Middle Eastern and North African Migrants and Refugees in High-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 7262. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197262