Children’s Temperament: A Bridge between Mothers’ Parenting and Aggression

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Basic Descriptive Statistics and Correlational Analysis in the Total Sample and by Gender

3.2. Mediational Analysis

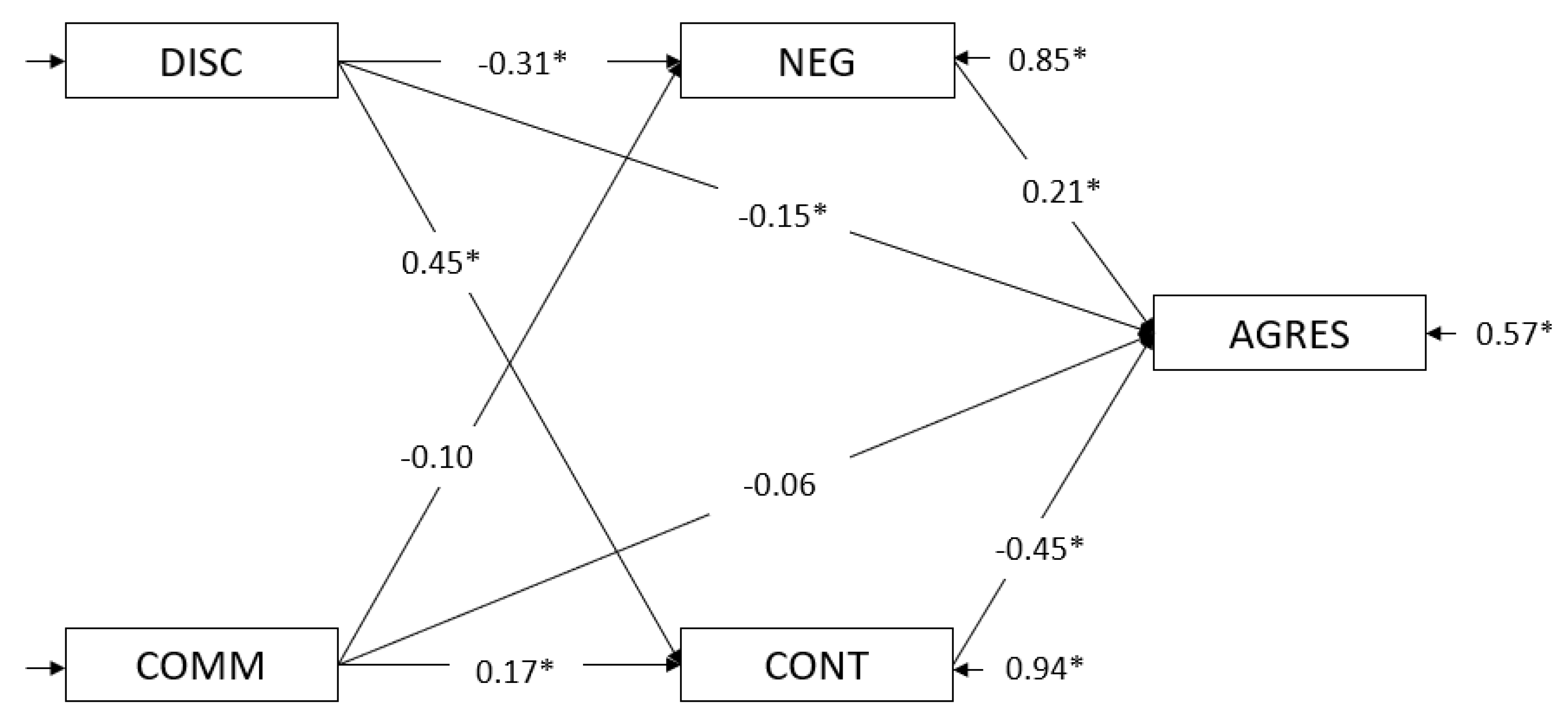

3.2.1. Direct and Mediating Effects in the Total Sample of 1–3 Year-Olds

Direct and Mediating Effects in the Sample of 1–3 Year-Olds by Gender

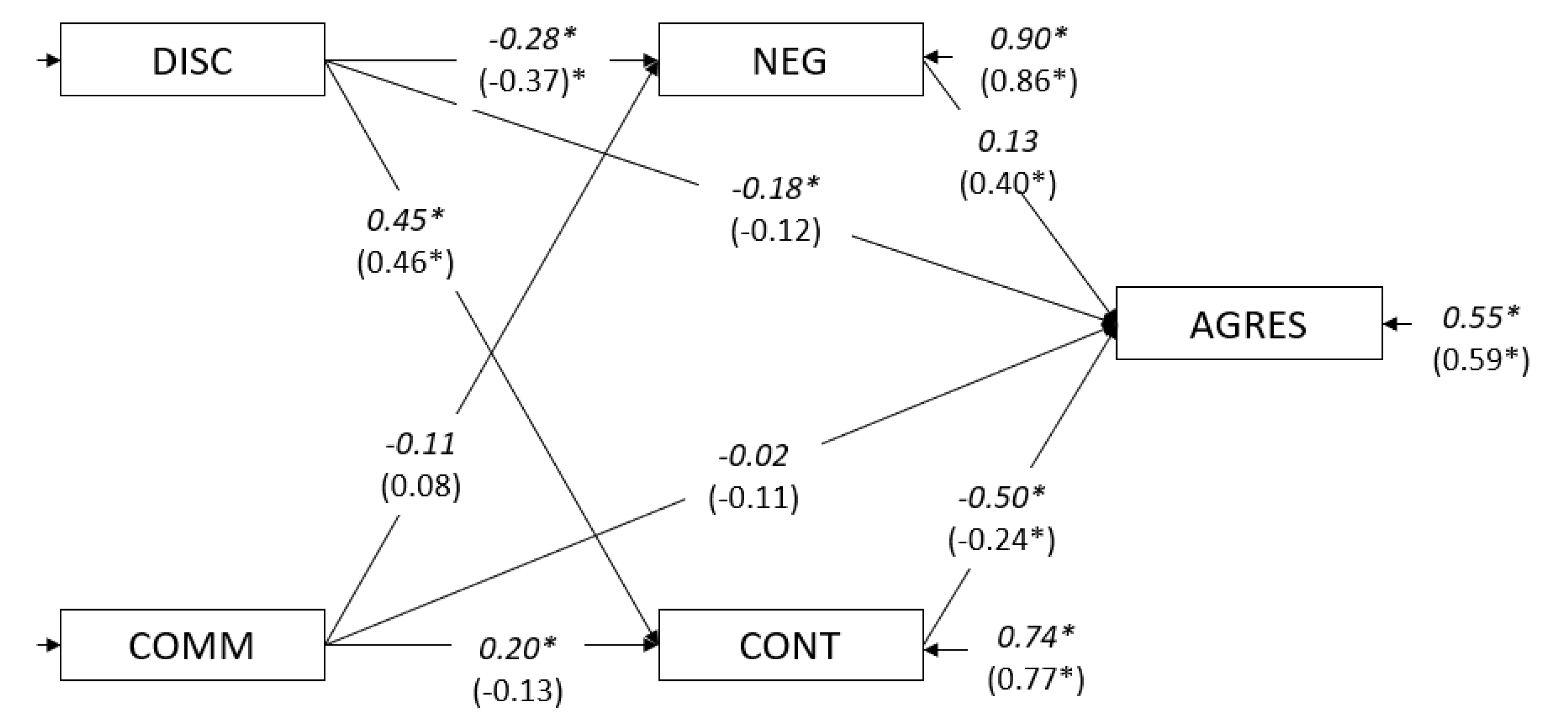

Direct and Mediating Effects in the Total Sample of 3–6-Year-Olds

Direct and Mediating Effects in the Sample of 3–6-Year-Olds by Gender

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brendgen, M.; Vitaro, F.; Tremblay, R.; Lavoie, F. Reactive and proactive aggression: Predictions to physical violence in different contexts and moderating effects of parental monitoring and caregiving behavior. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2001, 29, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahey, B.; Moffitt, T.; Caspi, A. Causes of Conduct Disorder and Juvenile Delinquency; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay, R.E. The development of aggressive behaviour during childhood: What have we learned in the past century? Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2000, 24, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, R.E.; Nagin, D.S.; Seguin, J.R.; Zoccolillo, M.; Zelazo, P.D.; Boivin, M.; Perusse, D.; Japel, C. Physical aggression during early childhood: Trajectories and predictors. Pediatrics 2004, 114, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eisenberg, N.; Spinrad, T.L.; Eggum, N.D. Emotion-related self-regulation and its relation to children’s maladjustment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 6, 495–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eisenberg, N.; Smith, C.; Spinrad, T. Effortful control. Relations with emotion regulation, adjustment and socialization in childhood. In Handbook of Self-Regulation: Research, Theory, and Applications; Vohs, K.D., Baumeister, R.F., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 263–283. [Google Scholar]

- Combs-Ronto, L.A.; Olson, S.L.; Lunkenheimer, E.S.; Sameroff, A.J. Interactions between maternal parenting and children’s early disruptive behavior: Bidirectional associations across the transition from preschool to school entry. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2009, 37, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eisenberg, N.; Cumberland, A.; Spinrad, T.L. Parental socialization of emotion. Psychol. Inq. 1998, 9, 241–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kiff, C.J.; Lengua, L.J.; Zalewski, M. Nature and nurturing: Parenting in the context of child temperament. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 14, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klein, M.R.; Lengua, L.J.; Thompson, S.F.; Moran, L.; Ruberry, E.J.; Kiff, C.; Zalewski, M. Bidirectional relations between temperament and parenting predicting preschool-age Children’s adjustment. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2018, 47, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Deater-Deckard, K.; Bell, M.A. The role of temperament by family environment interactions in child maladjustment. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2014, 42, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Childs, A.W.; Fite, P.J.; Moore, T.M.; Lochman, J.E.; Pardini, D.A. Bidirectional associations between parenting behavior and child callous-unemotional traits: Does parental depression moderate this link? J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2014, 42, 1141–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidov, M.; Grusec, J.E. Untangling the links of parental responsiveness to distress and warmth to child outcomes. Child Dev. 2006, 77, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antúnez, Z.; de la Osa, N.; Granero, R.; Ezpeleta, L. Reciprocity between parental psychopathology and oppositional symptoms from preschool to middle childhood. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 74, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maccoby, E. Parenting and its effects on children: On reading and misreading behavior genetics. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2000, 51, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeod, D.; Weisz, J.R.; Wood, J.J. Examining the association between parenting and childhood depression: A meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 27, 986–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flouri, E.; Midouhas, E.; Narayanan, M.K. The relationship between father involvement and child problem behaviour in intact families: A 7-year cross-lagged study. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2016, 44, 1011–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flouri, E.; Narayanan, M.K.; Midouhas, E. The cross-lagged relationship between father absence and child problem behaviour in the early years. Child Dev. 2015, 41, 1090–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Papp, L.M.; Cummings, E.M.; Goeke-Morey, M.C. Parental psychological distress, parent–child relationship qualities, and child adjustment: Direct, mediating, and reciprocal pathways. Parent Sci. Pract. 2005, 5, 259–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Uclés, I.; González-Calderón, M.J.; del Barrio-Gándara, V.; Carrasco, M.A. Perceived Parental Acceptance-Rejection and Children’s Psychological Adjustment: The Moderating Effects of Sex and Age. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 1336–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capatides, J.B.; Bloom, L. Underlying process in the socialization of emotion. In Advances in Infancy Research; Rovee-Collier, C., Lipsitt, L., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1993; pp. 99–135. [Google Scholar]

- Bridges, L.J.; Grolnick, W.S. The development of emotional self-regulation in infancy and early childhood. Soc. Sci. Dev. J. 1995, 15, 185–211. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, L.; Blatt-Eisengart, I.; Cauffman, E. Patterns of competence and adjustment among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful homes: A replication in a sample of serious juvenile offenders. J. Adolesc. Res. 2006, 16, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Degnan, K.; Calkins, S.; Keane, S.; Hill-Soderlund, A. Profiles of disruptive behavior across early childhood: Contributions of frustration reactivity, physiological regulation, and maternal behavior. Child Dev. 2008, 79, 1357–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Scaramella, L.V.; Sohr-Preston, S.L.; Mirabile, S.P.; Callahan, K.L.; Robison, S. Parenting and children’s distress reactivity during toddlerhood: An examination of direction of effects. Soc. Sci. Dev. J. 2008, 17, 578–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, N.A.; Schrock, M.; Woodruff-Borden, J. Child internalizing symptoms: Contributions of child temperament, maternal negative affect, and family functioning. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2011, 42, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, B.; Carrasco, M.A.; González-Peña, P.; Holgado-Tello, F.P. Temperament and behavioral problems in young children: The protective role of extraversion and effortful control. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 3232–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, P.J.; Morris, A.S. Temperament and developmental pathways to conduct problems. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 2004, 33, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigg, J.T. Temperament and developmental psychopathology. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 2006, 47, 395–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meesters, C.; Muris, P.; Van Rooijen, B. Reactive and regulative temperament factors and childpsychopathology: Relations of neuroticism and attentional control with symptoms of anxiety and aggression. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2007, 29, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathert, J.; Fite, P.J.; Gaertner, A.E. Associations between effortful control, psychological control and proactive and reactive aggression. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2011, 42, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Farver, J.A.M.; Zhang, Z. Temperament, harsh and indulgent parenting, and Chinese children’s proactive and reactive aggression. Child Dev. 2009, 80, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, E.M.; Cummings, J.L. A process-oriented approach to children’s coping with adults’ angry behavior. Dev. Rev. 1988, 8, 296–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Fabes, R.A. Emotion, regulation, and the development of social competence. In Review of Personality and Social Psychology; Clark, M.S., Ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Newbury, New York, NY, USA, 1992; Volume 14, pp. 119–150. [Google Scholar]

- Liew, J.; Eisenberg, N.; Reiser, M. Preschoolers’ effortful control and negative emotionality, immediate reactions to disappointment, and quality of social functioning. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2004, 89, 298–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Main, A.; Wang, Y. The relations of temperamental effortful control and anger/frustration to Chinese children’s academic achievement and social adjustment: A longitudinal study. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 102, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rothbart, M.K.; Bates, J.E. Temperament. Social, emotional, and personality development. In Handbook of Child Psychology; Eisenberg, N., Damon, W., Lerner, R.M., Eds.; Wiley Hoboken: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Volume 6, pp. 99–166. [Google Scholar]

- Nachmias, M.; Gunnar, M.; Mangelsdorf, S.; Parritz, R.H.; Buss, K. Behavioral inhibition and stress reactivity: The moderating role of attachment security. Child Dev. 1996, 67, 508–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stifter, C.A.; Moyer, D. The regulation of positive affect: Gaze aversion activity during mother-infant interaction. Infant Behav. Dev. 1991, 14, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, S.L.; Bates, J.E.; Sandy, J.M.; Schilling, E.M. Early developmental precursors of impulsive and inattentive behavior: From infancy to middle childhood. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2002, 43, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, M.I.; Rothbart, M.K. Developing mechanisms of self-regulation. Dev. Psychopathol. 2000, 12, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brody, G.H.; Murry, V.M.; Kim, S.; Brown, A.C. Longitudinal pathways to competence and psychological adjustment among African American children living in rural single-parent households. Child Dev. 2002, 73, 1505–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, G.H.; Murry, V.M.; McNair, L.; Chen, Y.; Gibbons, F.X.; Gerrard, M.; Wills, T.A. Linking changes in parenting to parent–child relationship quality and youth self-control: The strong African American families program. J. Res. Adolesc. 2005, 15, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Fabes, R.A.; Shepard, S.A.; Guthrie, I.K.; Murphy, B.C.; Reiser, M. Parental reactions to children’s negative emotions: Longitudinal relations to quality of children’s social functioning. Child Dev. 1999, 70, 513–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachs, T.D. Synthesis: Promising research designs, measures, and strategies. In Conceptualization and Measurement of Organism-Environment Interaction; Wachs, T.D., Plomin, R., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1991; pp. 162–182. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, A.; Hart, C.H.; Robinson, C.C.; Olsen, S. Children’s sociable and aggressive behavior with peers: A comparison of the US and Australia, and contributions of temperament and parenting styles. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2003, 27, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongers, I.L.; Koot, H.M.; Van Der Ende, J.; Verhulst, F.C. Developmental trajectories of externalizing behaviors in childhood and adolescence. Child Dev. 2004, 75, 1523–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Else-Quest, N.M.; Hyde, J.S.; Goldsmith, H.H.; Van Hulle, C.A. Gender differences in temperament: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Silverman, I.W. Gender differences in resistance to temptation: Theories and evidence. Dev. Rev. 2003, 23, 219–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollinshead, A. Five Factor Index of Social Position; Yale University: New Haven, CT, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Gartstein, M.A.; Rothbart, M.K. Studying infant temperament via the revised infant behavior questionnaire. Infant Behav. Dev. 2003, 26, 64–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, S.; Gartstein, M.; Rothbart, M. Measurement of fine-grained aspects of toddler temperament: The early childhood behavior questionnaire. Infant Behav. Dev. 2006, 29, 386–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rothbart, M.; Ahadi, S.; Hershey, K.; Fisher, P. Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: The Children’s Behavior Questionnaire. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 1394–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Peña, P.; Carrasco, M.; Gordillo, R.; Del Barrio, M.; Holgado-Tello, F.P. La agresión infantil de cero a seis años (Spanish Edition), 1st ed.; Vision Libros: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart, M. Temperament, development and personality. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 16, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, T.M.; Rescorla, L.A. Manual for the ASEBA Preschool Forms & Profiles; University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry: Burlington, VT, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gerard, A. Parent-Child Relationship Inventory (PCRI): Manual; Western Psycological Services: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Roa, L.R.; Del Barrio, V. Adaptación del cuestionario de crianza parental (PCRI-M) a población española. Rev. Lat. Psicol. 2001, 33, 329–341. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holgado-Tello, F.P.; Suárez, J.C.; Morata-Ramírez, M.Á. Modelos de Ecuaciones Estructurales, desde el” Path Analysis” al Análisis Multigrupo: Una Guía Práctica con LISREL; Sanz y Torres: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. LISREL 8.54 for Windows. Computer software. Scientific Software International: Lincolnwood. J. Appl. Econ. 2003, 19, 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- Bandalos, D.L. Factors influencing cross-validation of confirmatory factor analysis models. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1993, 28, 351–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, S.L.; Bates, J.E.; Bayles, K. Early antecedents of childhood impulsivity: The role of parent–child interaction, cognitive competence, and temperament. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 1990, 18, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- González-Peña, P.; Egido, B.D.; Carrasco, M.Á.; Holgado-Tello, F. Aggressive behavior in children: The role of temperament and family socialization. Span. J. Psychol. 2013, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cipriano, E.A.; Stifter, C.A. Predicting preschool effortful control from toddler temperament and parenting behavior. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2010, 31, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gartstein, M.A.; Putnam, S.P.; Rothbart, M.K. Etiology of school behavior problems: Contributions of temperament attributes in early childhood. J. Infant Ment. Health 2012, 33, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochanska, G.; Knaack, A. Effortful control as a personality characteristic of young children: Antecedents, correlates, and consequences. J. Pers. 2003, 71, 1087–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, J.L.; Clarke-Stewart, K.A. Trajectories of externalizing behavior from age 2 to age 9: Relations with gender, temperament, ethnicity, parenting, and rater. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 44, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolon-Arroyo, B.; Arnold, D.H.; Breaux, R.P.; Harvey, E.A. Reciprocal relations between parenting behaviors and conduct disorder symptoms in preschool children. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2018, 49, 786–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, K.E.; Boeldt, D.L.; Corley, R.P.; DiLalla, L.; Friedman, N.P.; Hewitt, J.K.; Rhee, S.H. Correlates of Positive Parenting Behaviors. Behav. Genet. 2018, 48, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Castagna, P.J.; Babinski, D.E.; Pearl, A.M.; Waxmonsky, J.G.; Waschbusch, D.A. Initial Investigation of the Psychometric Properties of the Limited Prosocial Emotions Questionnaire (LPEQ). Assessment 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heflin, B.H.; Heymann, P.; Coxe, S. Impact of Parenting Intervention on Observed Aggressive Behaviors in At-Risk Infants. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2020, 29, 2234–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total Sample | Boys | Girls | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | |

| DISC | 30.31 | 4.66 | 30.03 | 4.65 | 30.62 | 4.66 |

| COMM | 22.74 | 2.70 | 22.74 | 2.78 | 22.73 | 2.62 |

| NEG * | 3.65 | 0.66 | 3.72 | 0.64 | 3.56 | 0.67 |

| AGRES * | 15.57 | 8.32 | 16.62 | 8.60 | 14.35 | 7.84 |

| CONT | 280.44 | 30.33 | 278.03 | 29.58 | 283.21 | 31.03 |

| DISC | COMM | NEG | AGRES | CONT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DISC | --- | −0.11 * | −0.37 ** | −0.36 ** | 0.20 ** |

| COMM | 0.09 (−0.11) | --- | −0.05 | −0.14 * | −0.04 |

| NEG | −0.38 ** (−0.34 **) | −0.09 (−0.01) | --- | 0.65 ** | −0.43 ** |

| AGRES | −0.39 ** (−0.30 **) | −0.15 (−0.13) | 0.61 ** (0.69 **) | --- | −0.41 ** |

| CONT | 0.16 * (0.23 **) | −0.04 (−0.03) | −0.39 ** (−0.47 **) | −0.31 ** (−0.53 **) | --- |

| Total Sample | Boys | Girls | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | |

| DISC | 30.74 | 4.46 | 30.46 | 4.20 | 31.09 | 4.78 |

| COMM | 21.49 | 2.70 | 21.42 | 2.70 | 21.58 | 2.70 |

| NEG | 4.24 | 0.64 | 4.22 | 0.63 | 4.21 | 0.58 |

| AGRES * | 4.22 | 0.61 | 9.30 | 5.48 | 6.99 | 4.63 |

| CONT * | 8.38 | 5.26 | 4.12 | 0.65 | 4.41 | 0.58 |

| DISC | COMM | NEG | AGRES | CONT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DISC | --- | 0.08 | −0.32 ** | −0.43 ** | 0.46 ** |

| COMM | −0.11 (0.03) | --- | −0.13 ** | −0.19 ** | 0.21 ** |

| NEG | −0.29 ** (−0.37 **) | −0.15 * (−0.09) | --- | 0.41 ** | −0.33 ** |

| AGRES | −0.46 ** (−0.39 **) | −0.19 * (−0.20) | 0.34 **(0.55 **) | --- | −0.60 ** |

| CONT | 0.47 * (0.46 **) | 0.25 ** (0.14) | −0.31 **(−0.39 **) | −0.63 ** (−0.47 **) | --- |

| Mod. | RMSEA | GFI | AGFI | ECVI | CAIC | χ2 | d.f. | p | Δχ2 | Δd.f. | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–3 Years Old | |||||||||||

| 1.1 | 0.33 | 0.73 | 0.50 | 0.97 | 230.50 | 216.25 | 8 | <0.01 | --- | --- | --- |

| 1.2 | 0.36 | 0.76 | 0.39 | 0.88 | 327.56 | 191.42 | 6 | <0.01 | --- | --- | --- |

| 1.3 | 0.36 | 0.92 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 149.28 | 53.98 | 2 | <0.01 | 137.48 | 4 | <0.01 |

| 1.1 Boys | 0.28 | 0.79 | 0.60 | 0.79 | 135.46 | 93.92 | 8 | <0.01 | |||

| 1.2 Boys | 0.28 | 0.80 | 0.49 | 0.78 | 141.58 | 88.17 | 6 | <0.01 | |||

| 1.3 Boys | 0.29 | 0.93 | 0.50 | 0.37 | 102.03 | 24.88 | 2 | <0.01 | 63.29 | 4 | <0.01 |

| 1.1 Girls | 0.42 | 0.68 | 0.40 | 1.62 | 198.08 | 127.82 | 8 | <0.01 | |||

| 1.2 Girls | 0.45 | 0.71 | 0.27 | 1.46 | 188.12 | 111.36 | 6 | <0.01 | |||

| 1.3 Girls | 0.38 | 0.90 | 0.26 | 0.55 | 106.41 | 29.52 | 2 | <0.01 | 81.06 | 4 | <0.01 |

| 3–6 Years Old | |||||||||||

| 2.1 | 0.30 | 0.77 | 0.58 | 0.78 | 256.93 | 210.24 | 8 | < 0.01 | |||

| 2.2 | 0.32 | 0.83 | 0.57 | 0.71 | 245.54 | 148.08 | 6 | <0.01 | |||

| 2.3 | 0.13 | 0.98 | 0.88 | 0.15 | 94.07 | 9.61 | 2 | <0.01 | 236.47 | 4 | <0.01 |

| 2.1 Boys | 0.32 | 0.78 | 0.59 | 1.03 | 135.67 | 75.99 | 8 | <0.01 | |||

| 2.2 Boys | 0.32 | 0.83 | 0.58 | 0.77 | 148.93 | 75.82 | 6 | <0.01 | |||

| 2.3 Boys | 0.08 | 0.99 | 0.91 | 0.28 | 77.62 | 3.41 | 2 | 0.18 | 74.21 | 4 | <0.01 |

| 2.1 Girls | 0.35 | 0.76 | 0.54 | 1.13 | 222.14 | 139.45 | 8 | <0.01 | |||

| 2.2 Girls | 0.29 | 0.83 | 0.57 | 0.66 | 217.83 | 78.37 | 6 | <0.01 | |||

| 2.3 Girls | 0.17 | 0.97 | 0.80 | 0.22 | 91.85 | 11.55 | 2 | <0.01 | 66.82 | 4 | <0.01 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carrasco, M.A.; Delgado, B.; Holgado-Tello, F.P. Children’s Temperament: A Bridge between Mothers’ Parenting and Aggression. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6382. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176382

Carrasco MA, Delgado B, Holgado-Tello FP. Children’s Temperament: A Bridge between Mothers’ Parenting and Aggression. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(17):6382. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176382

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarrasco, Miguel A., Begoña Delgado, and Francisco Pablo Holgado-Tello. 2020. "Children’s Temperament: A Bridge between Mothers’ Parenting and Aggression" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 17: 6382. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176382

APA StyleCarrasco, M. A., Delgado, B., & Holgado-Tello, F. P. (2020). Children’s Temperament: A Bridge between Mothers’ Parenting and Aggression. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6382. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176382