The Prototypes of Tobacco Users Scale (POTUS) for Cigarette Smoking and E-Cigarette Use: Development and Validation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.1.1. Adult Online Study

2.1.2. Adult Randomized Clinical Trial (RCT)

2.1.3. Adolescent Study

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Prototypes

2.2.2. Other Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Scale Psychometrics

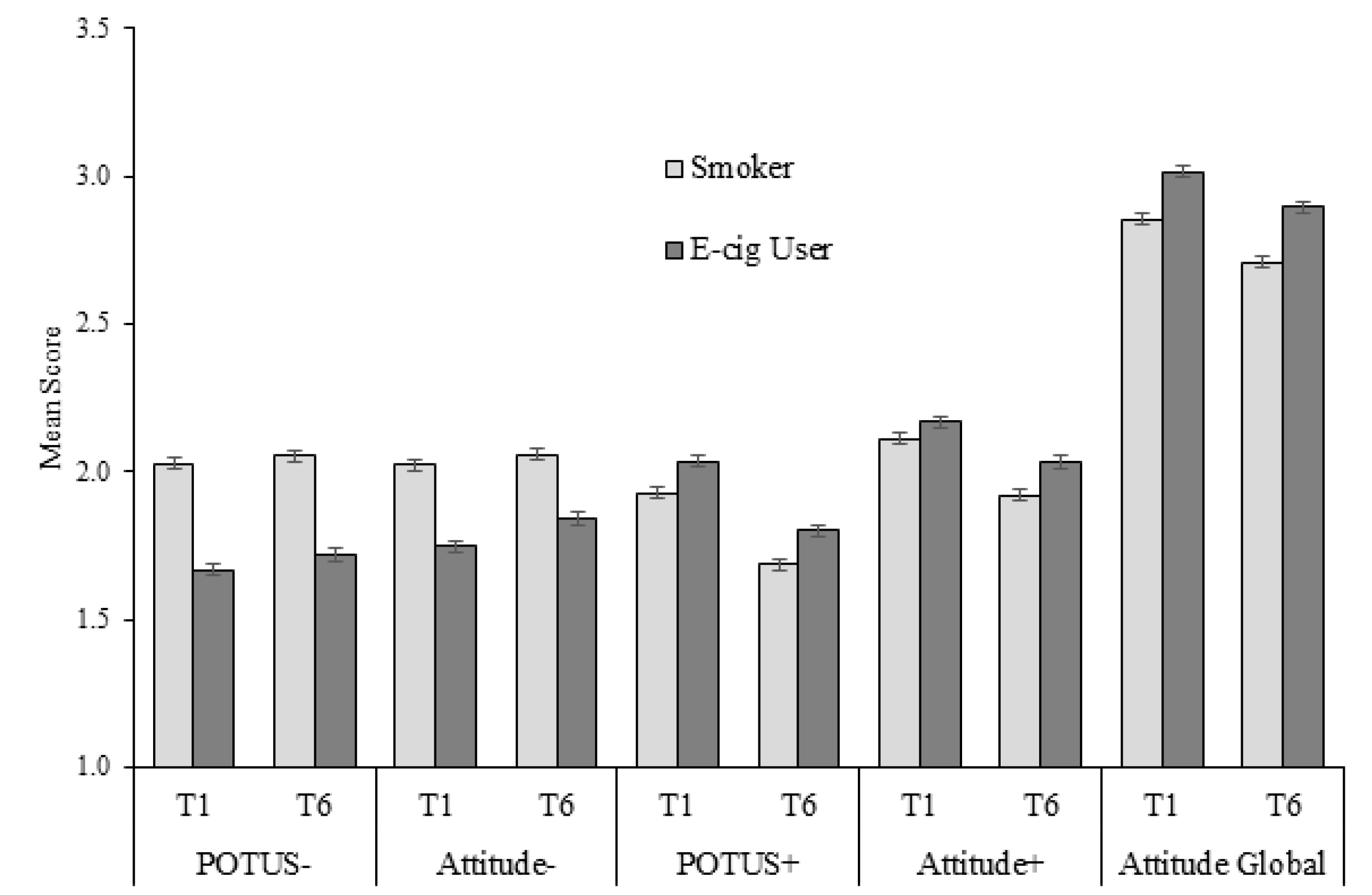

3.2. Smoker vs. E-Cigarette User Prototypes

3.3. Validity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gibbons, F.X.; Gerrard, M. Predicting young adults’ health risk behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, F.X.; Gerrard, M.; Blanton, H.; Russell, D.W. Reasoned action and social reaction: Willingness and intention as independent predictors of health risk. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 1164–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerrard, M.; Gibbons, F.X.; Houlihan, A.E.; Stock, M.L.; Pomery, E.A. A dual-process approach to health risk decision making: The prototype willingness model. Dev. Rev. 2008, 28, 29–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckhausen, J.; Wrosch, C.; Schulz, R. A motivational theory of life-span development. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 32–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Quinlan, S.L.; Jaccard, J.; Blanton, H. A decision theoretic and prototype conceptualization of possible selves: Implications for the prediction of risk behavior. J. Pers. 2006, 74, 599–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, J.A.; Hampson, S.; Barckley, M. The effect of subjective normative social images of smokers on children’s intentions to smoke. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2008, 10, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivis, A.; Sheeran, P.; Armitage, C.J. Explaining adolescents’ cigarette smoking: A comparison of four modes of action control and test of the role of self-regulatory mode. Psychol. Health 2010, 25, 893–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, F.X.; Gerrard, M. Predicting young adult’s health risk behavior. In Social Psychology of Health; Salovey, A.J.R.P., Salovey, P., Rothman, A.J., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, J.; Kothe, E.; Mullan, B.; Monds, L. Reasoned versus reactive prediction of behaviour: A meta-analysis of the prototype willingness model. Health Psychol. Rev. 2016, 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gibbons, F.X.; Eggleston, T.J. Smoker networks and the typical smoker: A prospective analysis of smoking cessation. Health Psychol. 1996, 15, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.G.; Ribisl, K.M.; Brewer, N.T. Smokers’ and nonsmokers’ beliefs about harmful tobacco constituents: Implications for Fda communication efforts. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2014, 16, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gibbons, F.X.; Gerrard, M.; Lando, H.A.; McGovern, P.G. Social comparison and smoking cessation: The role of the typical smoker. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 27, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrard, M.; Gibbons, F.X.; Lane, D.J.; Stock, M.L. Smoking cessation: Social comparison level predicts success for adult smokers. Health Psychol. 2005, 24, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepper, J.K.; Reiter, P.L.; McRee, A.L.; Cameron, L.D.; Gilkey, M.B.; Brewer, N.T. Adolescent males’ awareness of and willingness to try electronic cigarettes. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 52, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Blanton, H.; Gibbons, F.X.; Gerrard, M.; Conger, K.J.; Smith, G.E. Role of family and peers in the development of prototypes associated with substance use. J. Fam. Psychol. 1997, 11, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCool, J.P.; Cameron, L.; Petrie, K. Stereotyping the smoker: Adolescents’ appraisals of smokers in film. Tob. Control 2004, 13, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gerrard, M.; Gibbons, F.X.; Stock, M.L.; Lune, L.S.; Cleveland, M.J. Images of smokers and willingness to smoke among African American pre-adolescents: An application of the prototype/willingness model of adolescent health risk behavior to smoking initiation. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2005, 30, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Singh, T.; Arrazola, R.A.; Corey, C.G.; Husten, C.G.; Neff, L.J.; Homa, D.M.; King, B.A. Tobacco use among middle and high school students--United States, 2011–2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2016, 65, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenborn, C.A.; Gindi, R.M. Electronic cigarette use among adults: United States. 2014. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db217.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2020).

- Pearson, J.L.; Richardson, A.; Niaura, R.S.; Vallone, D.M.; Abrams, D.B. E-cigarette awareness, use, and harm perceptions in US adults. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 1758–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, A.; Gentzke, A.; Hu, S.S.; Cullen, K.A.; Apelberg, B.J.; Homa, D.M.; King, B.A. Tobacco use among middle and high school students-United States, 2011–2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2017, 66, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nutt, D.J.; Phillips, L.D.; Balfour, D.; Curran, H.V.; Dockrell, M.; Foulds, J.; Fagerstrom, K.; Letlape, K.; Milton, A.; Polosa, R.; et al. Estimating the harms of nicotine-containing products using the mcda approach. Eur. Addict. Res. 2014, 20, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Perrine, C.G.; Pickens, C.M.; Boehmer, T.K.; King, B.A.; Jones, C.M.; DeSisto, C.L.; Duca, L.M.; Lekiachvili, A.; Kenemer, B.; Shamout, M.; et al. Characteristics of a multistate outbreak of lung injury associated with E-cigarette use, or Vaping-United States, 2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2019, 68, 860–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, M.; Cross, S.J.; Loughlin, S.E.; Leslie, F.M. Nicotine and the adolescent brain. J. Physiol. 2015, 593 Pt 16, 3397–3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Franza, J.R.; Rigotti, N.A.; McNeill, A.D.; Ockene, J.K.; Savageau, J.A.; Cyr, D.S.; Coleman, M. Initial symptoms of nicotine dependence in adolescents. Tob. Control 2000, 9, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrington-Trimis, J.L.; Urman, R.; Leventhal, A.M.; Gauderman, W.J.; Cruz, T.B.; Gilreath, T.D.; Howland, S.; Unger, J.B.; Berhane, K.; Samet, J.M.; et al. E-cigarettes, cigarettes, and the prevalence of adolescent tobacco use. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20153983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wills, T.A.; Sargent, J.D.; Knight, R.; Pagano, I.; Gibbons, F.X. E-cigarette use and willingness to smoke: A sample of adolescent non-smokers. Tob. Control 2016, 25, e52–e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhong, J.; Cao, S.; Gong, W.; Fei, F.; Wang, M. Electronic cigarettes use and intention to cigarette smoking among never-smoking adolescents and young adults: A meta-analysis. Int. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Paolacci, G.; Chandler, J. Inside the Turk: Understanding mechanical Turk as a participant pool. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 23, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buhrmester, M.; Kwang, T.; Gosling, S.D. Amazon’s mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 6, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peer, E.; Vosgerau, J.; Acquisti, A. Reputation as a sufficient condition for data quality on amazon mechanical Turk. Behav. Res. Methods 2014, 46, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, N.T.; Hall, M.G.; Noar, S.M.; Parada, H.; Stein-Seroussi, A.; Bach, L.E.; Hanley, S.; Ribisl, K.M. Effect of pictorial cigarette pack warnings on changes in smoking behavior: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodar, K.E.; Hall, M.G.; Butler, E.N.; Parada, H.; Stein-Seroussi, A.; Hanley, S.; Brewer, N.T. Recruiting diverse smokers: Enrollment yields and cost. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Peebles, K.; Hall, M.G.; Pepper, J.K.; Byron, J.B.; Noar, S.M.; Brewer, N.T. Adolescents’ responses to pictorial warnings on their parents’ cigarette packs. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 59, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fong, G.T.; Cummings, K.M.; Borland, R.; Hastings, G.; Hyland, A.; Giovino, G.A.; Hammond, D.; Thompson, M.E. The conceptual framework of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Policy Evaluation Project. Tob. Control 2006, 15 (Suppl. 3), iii3–iii11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Klein, W.M.; Zajac, L.E.; Monin, M.M. Worry as a moderator of the association between risk perceptions and quitting intentions in young adult and adult smokers. Ann. Behav. Med. 2009, 38, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, C.J. Efficacy of a brief worksite intervention to reduce smoking: The roles of behavioral and implementation intentions. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, A.; Brosschot, J. Worry about health in smoking behaviour change. Behav. Res. Ther. 2003, 41, 1081–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranby, K.W.; Lewis, M.A.; Toll, B.A.; Rohrbaugh, M.J.; Lipkus, I.M. Perceptions of smoking-related risk and worry among dual-smoker couples. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2013, 15, 734–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodie, C.; Mackintosh, A.M.; Hastings, G.; Ford, A. Young adult smokers’ perceptions of plain packaging: A pilot naturalistic study. Tob. Control 2011, 20, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fathelrahman, A.I.; Omar, M.; Awang, R.; Cummings, K.M.; Borland, R.; Samin, A.S.B.M. Impact of the new Malaysian cigarette pack warnings on smokers’ awareness of health risks and interest in quitting smoking. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2010, 7, 4089–4099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.G.; Pepper, J.K.; Morgan, J.C.; Brewer, N.T. Social interactions as a source of information about E-cigarettes: A study of U.S. adult smokers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borland, R.; Hill, D. Initial impact of the new Australian tobacco health warnings on knowledge and beliefs. Tob. Control 1997, 6, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, L.; Borland, R.; Fong, G.T.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, L.; Thrasher, J.F. Smoking-related thoughts and microbehaviours, and their predictive power for quitting. Tob. Control 2015, 24, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McClave, A.K.; Whitney, N.; Thorne, S.L.; Mariolis, P.; Dube, S.R.; Engstrom, M. Adult tobacco survey—19 States, 2003–2007. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2010, 59, 1–75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bollen, K.A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Steiger, J.H. Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1990, 25, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Eijnden, R.J.; Spijkerman, R.; Engels, R.C. Relative contribution of smoker prototypes in predicting smoking among adolescents: A comparison with factors from the theory of planned behavior. Eur. Addict. Res. 2006, 12, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hukkelberg, S.S.; Dykstra, J.L. Using the prototype/willingness model to predict smoking behaviour among Norwegian adolescents. Addict. Behav. 2009, 34, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piko, B.F.; Bak, J.; Gibbons, F.X. Prototype perception and smoking: Are negative or positive social images more important in adolescence? Addict. Behav. 2007, 32, 1728–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Gardner, W.L.; Berntson, G.G. Beyond bipolar conceptualizations and measures: The case of attitudes and evaluative space. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 1997, 1, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.A.; Larsen, J.T.; Smith, N.K.; Cacioppo, J.T. Negative information weighs more heavily on the brain: The negativity bias in evaluative categorizations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 75, 887–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAfee, T.; Davis, K.C.; Alexander, R.L.; Pechacek, T.F.; Bunnell, R. Effect of the first federally funded us antismoking national media campaign. Lancet 2013, 382, 2003–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Forster, J.L. Beliefs and experimentation with electronic cigarettes: A prospective analysis among young adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 46, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Prototype Adjectives | Gibbons [12] | Gibbons [10] | Gerrard [13] | Gibbons [1] | Pepper [14] | Blanton [15] | McCool [16] | Gerrard [17] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social status | ||||||||

| Popular | Y | T | C | |||||

| Cool or sophisticated | Y | Y | T | C | ||||

| Trashy | Y | |||||||

| Classy | Y | |||||||

| Social interaction | ||||||||

| Friendly | A | A | A | |||||

| Outgoing | A | |||||||

| Self-assured | A | |||||||

| Self-confident | Y | T | T | |||||

| Intelligence and cognition | ||||||||

| Smart | A | A | Y | T | C, T | C | ||

| Confused | Y | T | ||||||

| Irrational | A | A | ||||||

| Intelligent | Y | C, T | ||||||

| Physical attractiveness | ||||||||

| (Un)attractive | A | A | Y | Y | T | |||

| Good-looking | C | |||||||

| Stylish | Y | C, T | ||||||

| Sexy | Y | C, T | ||||||

| Self-focused | ||||||||

| (In)considerate | A | A | A | Y | Y | T | ||

| Self-centered | A | A | Y | Y | T | |||

| Motivated | ||||||||

| Hardworking | A | |||||||

| Determined | A | |||||||

| Careless | Y | T | ||||||

| (In)dependent | A | A | Y | Y | T | T | ||

| Reliable | A | A | ||||||

| Tough | Y | C, T | ||||||

| Hard | C, T | |||||||

| Emotional and physical health | ||||||||

| Depressed | C, T | |||||||

| Moody | A | A | ||||||

| Weak | A | A | C, T | |||||

| Bored | C, T | |||||||

| Stressed | C, T | |||||||

| Healthy | C, T | |||||||

| Other | ||||||||

| Foolhardy | A | |||||||

| Dull [boring] | Y | T | C | |||||

| Immature | Y | Y | T | |||||

| Honest | A | A | ||||||

| Angry | C, T |

| Adult Online Study | Adult RCT c | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoker POTUS+ | Smoker POTUS– | Smoker POTUS+ | Smoker POTUS– | |||

| n | r | r | n | r | r | |

| Convergent Validity—Cigarette Smoking | ||||||

| Cigarette smoking | ||||||

| Current smoker (%) | 1414 | 0.36 * | −0.42 * | |||

| Frequency (cigarettes/day) a | 221 | −0.02 | −0.06 | 2121 | −0.06 * | −0.02 |

| Quit intentions a | 360 | −0.17 * | 0.16 * | 2121 | −0.07 * | 0.26 * |

| Cigarette attitudes and beliefs | ||||||

| Positive subjective norms about quitting smoking | 2099 | −0.08 * | 0.22 * | |||

| Worry about consequences of smoking | 2003 | −0.09 * | 0.37 * | |||

| Positive pack attitudes | 2053 | 0.14 * | −0.12 * | |||

| Negative pack attitudes | 1989 | −0.09 * | 0.35 * | |||

| Thinking about harms of smoking b | 1876 | −0.00 | 0.20 * | |||

| Negative consequences of smoking | 2085 | −0.19 * | 0.41 * | |||

| Predictive Validity (assessed at Week 4 of trial) | ||||||

| Forgoing a cigarette in past week | 1704 | β = −0.05 * | β = 0.16 * | |||

| Cigarette smoking quit attempt in past week | 1880 | OR = 1.07 d | OR = 1.27 * e | |||

| E-Cigarette POTUS+ | E-Cigarette POTUS– | |||||

| n | r | r | ||||

| Convergent Validity—E-cigarette Use | ||||||

| E-cigarette use | ||||||

| Current user (n (%)) | 2094 | 0.13 * | −0.08 * | |||

| Frequency (days/week) | 525 | 0.09 * | 0.04 | |||

| E-cigarette social interactions and ads | ||||||

| Conversation about e-cigarettes in last month | 2104 | 0.10 * | −0.01 | |||

| Use e-cigarettes because friends or family use them | 526 | 0.08 | −0.04 | |||

| Ever recommended that someone use e-cigarettes | 2102 | 0.19 * | −0.08 * | |||

| Saw or heard e-cigarette advertisement in last 30 days | 1677 | −0.00 | −0.03 | |||

| Adult Online Study | Adult RCT, T1 | Adult RCT, T6 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoker | POTUS+ | POTUS– | POTUS+ | POTUS– | POTUS+ | POTUS– |

| Attitude+ | 0.39 * | −0.32 * | 0.25 * | −0.15 * | 0.37 * | −0.14 * |

| Attitude− | −0.30 * | 0.61 * | −0.04 | 0.38 * | −0.05 * | 0.49 * |

| Attitude Global | 0.45 * | −0.60 * | 0.22 * | −0.25 * | 0.24 * | −0.39 * |

| E-Cigarette User | POTUS+ | POTUS– | POTUS+ | POTUS– | POTUS+ | POTUS– |

| Attitude+ | 0.50 * | −0.33 * | 0.42 * | −0.21 * | 0.44 * | −0.15 * |

| Attitude– | −0.32 * | 0.63 * | −0.14 * | 0.38 * | −0.10 * | 0.44 * |

| Attitude Global | 0.55 * | −0.55 * | 0.37 * | −0.33 * | 0.31 * | −0.34 * |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Butler, E.N.; Hall, M.G.; Chen, M.S.; Pepper, J.K.; Blanton, H.; Brewer, N.T. The Prototypes of Tobacco Users Scale (POTUS) for Cigarette Smoking and E-Cigarette Use: Development and Validation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6081. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176081

Butler EN, Hall MG, Chen MS, Pepper JK, Blanton H, Brewer NT. The Prototypes of Tobacco Users Scale (POTUS) for Cigarette Smoking and E-Cigarette Use: Development and Validation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(17):6081. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176081

Chicago/Turabian StyleButler, Eboneé N., Marissa G. Hall, May S. Chen, Jessica K. Pepper, Hart Blanton, and Noel T. Brewer. 2020. "The Prototypes of Tobacco Users Scale (POTUS) for Cigarette Smoking and E-Cigarette Use: Development and Validation" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 17: 6081. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176081

APA StyleButler, E. N., Hall, M. G., Chen, M. S., Pepper, J. K., Blanton, H., & Brewer, N. T. (2020). The Prototypes of Tobacco Users Scale (POTUS) for Cigarette Smoking and E-Cigarette Use: Development and Validation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6081. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176081