In Their Own Words: A Qualitative Investigation of the Factors Influencing Maternal Postpartum Functioning in the United States

Abstract

1. Introduction

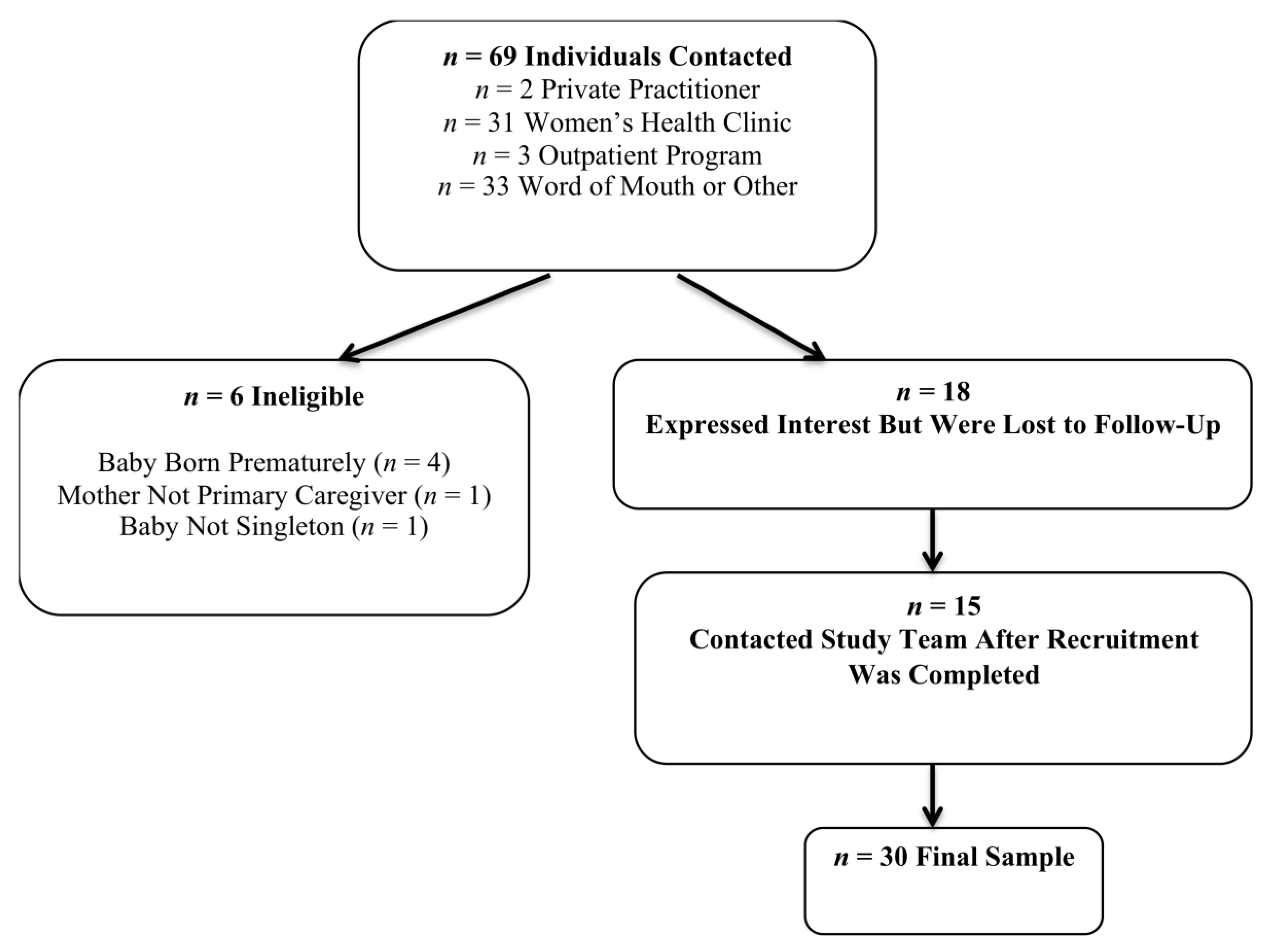

2. Materials and Methods

- An analysis of task requirements, or what is required to function well in that domain;

- An attributional analysis of experience, or what has helped or hindered function in that domain in the past;

- An assessment of situational resources and constraints, or how equipped one feels to function well in that domain in their current personal and situational context.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Factors Impacting Maternal Postpartum Functioning: Qualitative Themes

3.2.1. Accurate Locus of Control, Limiting Inappropriate Self-Blame

“[Moms who were struggling to breastfeed] were doing this triple pump thing where you feed the baby and pump, and then you give it a bottle, and then you do this and you do that, like ten times a day. And they felt like they were failing because it wasn’t working. And I feel like that was kind of the most eye-opening thing to me that they were spending all this time dedicated to their babies and still felt like they were doing a bad job.”

3.2.2. Adaptive Attitude towards Learning and Adjustment

“at the time, … it seemed very important to feed him a particular way and I was attached to ultimately being able to do that. And it’s hard when you’re that emotional and hormonal and sleep-deprived to … realign your expectations so dramatically from what you thought they would be.”

3.2.3. Bond with Baby

3.2.4. Child Temperament

“I think me being calm and knowing that he’s okay and if he cries, just going through the checklist. Did he eat, did he sleep, did he poop? If he had all his things, then maybe he needs one extra feed or a little bit more sleep or whatever. But … if he did everything today, then he is good.”

3.2.5. Emotion Regulation

3.2.6. Financial and Material Resources

3.2.7. Gaining Firsthand Experience with Parenting Activities

3.2.8. Giving Oneself Credit for Successes

“she was having fun, so I was having fun. There wasn’t no crying, there was nothing, she was laughing the whole time. She was having fun, and I felt proud of myself because I did everything, and I set everything up, and it was just- … just everything was nice. I was happy.”

3.2.9. Insufficient Time for Task Demands

3.2.10. Internal Aspects of Engagement with Social Support

3.2.11. Keeping Baby in a Routine

3.2.12. Knowledge Access

“for me, it’s like what the data says, more I guess because of my background and my own child. But it’s everything data, data, data. And people can give you their opinions. But I’d like to see what the research actually says. Reading a great new book called Crib Sheet, which is like the data-driven guide to more relaxed parenting.”

“having the opinion from other people. Maybe what people usually do. That’s also helpful to kind of compare what you’re doing with what other people are doing. Not in a negative way but just to have somebody else’s experience so that you can kind of know if you’re doing good or not.”

3.2.13. Maintaining Aspects of Life Outside of Parenting

“I was a workaholic before this, and it’s really weird to not feel like I’ve contributed or really done something in a day, and I need to be more okay with taking care of the baby as doing something, but you just feel like you’re sitting on a couch all day long.”

3.2.14. Mother’s Self-Knowledge

3.2.15. Physical Home Environment

3.2.16. Prioritization of Self-Care

“I watched other people kind of struggle with that and feel like they couldn’t leave the house between certain times of the day and it was just not great. So I knew I had the time that I wanted to be able to do things and go out and enjoy my time at home.”

3.2.17. Sleep and Fatigue

3.2.18. Social Pressures

3.2.19. Strategic Planning and Time Management

“My husband was home from work that day, so I was able to lean on him to watch the kids, but that also involved me preparing a lot of stuff to be able to leave because he’s not the typical day-to-day caregiver, so I had to make sure he had all the tools he needed to sort of keep their routine in place or keep them satisfied.”

3.2.20. Support from Others

3.2.21. Taking Breaks and Getting Out of the House

“you can’t take time for yourself completely if the baby’s around. You’re always going to be panicking… Go get some fresh air … When you’re near the baby, although you’re taking time for yourself but you’re still near the baby you’re still kind of worried about the baby.”

“I’m like her favorite person right now, so that is difficult when I’m like, ‘Just take the baby.’ And then in the morning, [my husband will] bring her downstairs, and she just wants to come back to be with me. I’m like, ‘I love you so much, but go away. I need like an hour, or like five minutes, or a breath.’”

3.2.22. Understanding Baby

3.2.23. Workplace Flexibility and Understanding

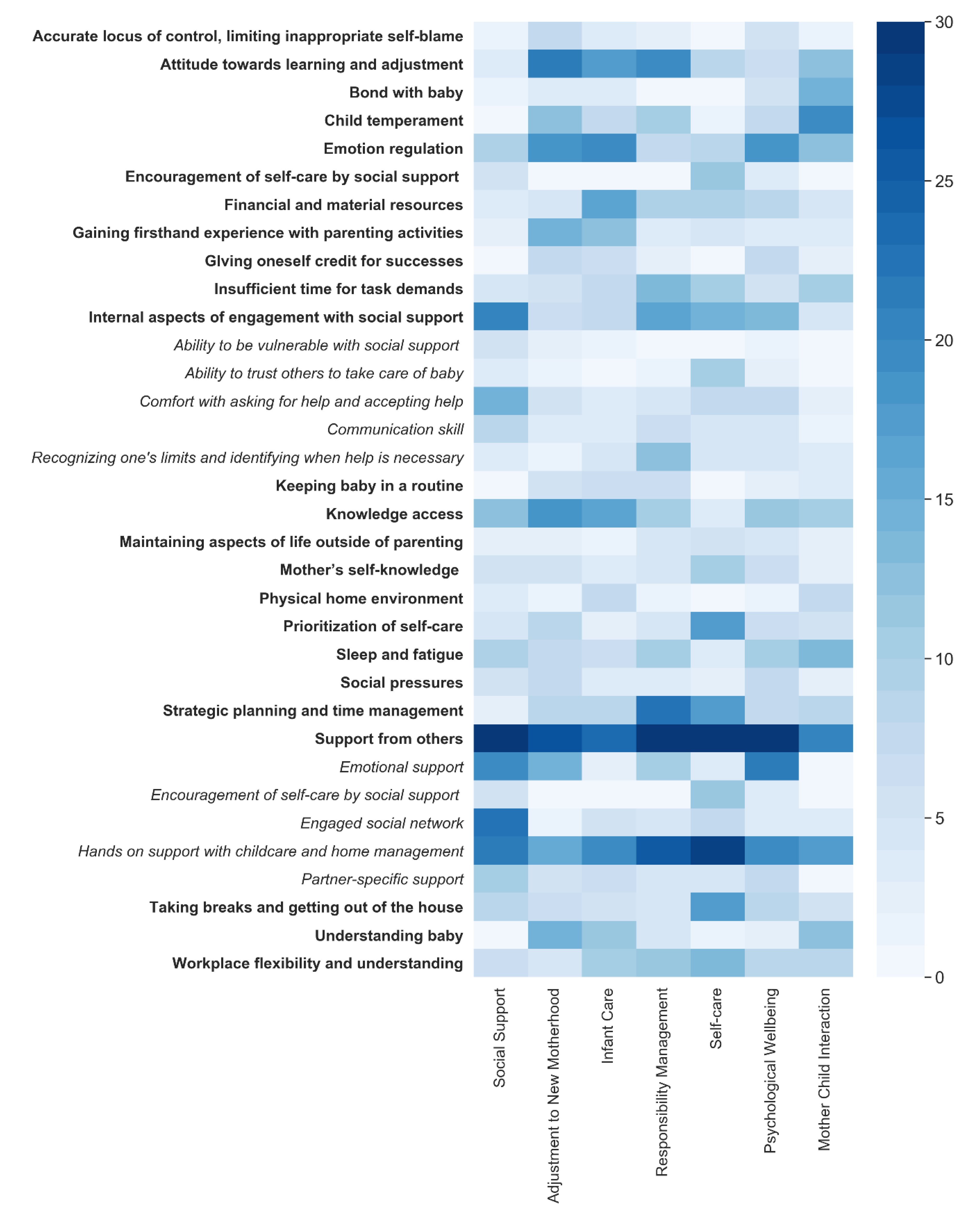

3.3. Heat Map of Factor Occurrence across Domains of Functioning

4. Discussion

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Domain: Infant Care

Appendix A.2. Domain: Mother–Child Interaction

Appendix A.3. Domain: Psychological Wellbeing

Appendix A.4. Domain: Social Support

Appendix A.5. Domain: Responsibility Management

Appendix A.6. Domain: Adjustment to New Motherhood

Appendix A.7. Domain: Self-Care

References

- Logsdon, M.C.; Wisner, K.L.; Pinto-Foltz, M.D. The impact of postpartum depression on mothering. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2006, 35, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowles, E.R.; Horowitz, J.A. Clinical assessment of mothering during infancy. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2006, 35, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albers, L.L. Health problems after childbirth. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2000, 45, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newport, D.J.; Hostetter, A.; Arnold, A.; Stowe, Z.N. The treatment of postpartum depression: Minimizing infant exposures. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2002, 3, 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Handler, A.; Zimmermann, K.; Dominik, B.; Garland, C.E. Universal Early Home Visiting: A Strategy for Reaching All Postpartum Women. Matern. Child Health J. 2019, 23, 1414–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahey, J.O.; Shenassa, E. Understanding and meeting the needs of women in the postpartum period: The perinatal maternal health promotion model. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2013, 58, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, C.R.; Martin, D.P.; Deyo, R.A. Health consequences of pregnancy and childbirth as perceived by women and clinicians. Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, 92, 842–848. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra-Reyes, L.; Christie, V.M.; Prabhakar, A.; Siek, K.A. Mind the gap: Assessing the disconnect between postpartum health information desired and health information received. Women’s Health Issues 2017, 27, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, T.L. The Mismatch Between Postpartum Services and Women’s Needs: Supermom Versus Lying-In. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2013, 58, 607–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhi, M.; Stirling, C.M.; Crisp, E.P. Mothers’ views of health problems in the 12 months after childbirth: A concept mapping study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 3702–3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suplee, P.D.; Bloch, J.R.; McKeever, A.; Borucki, L.C.; Dawley, K.; Kaufman, M. Focusing on maternal health beyond breastfeeding and depression during the first year postpartum. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. Clin. Scholarsh. Care Women Childbear Fam. Newborns 2014, 43, 782–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkin, J.L.; Wisner, K.L.; Bromberger, J.T.; Beach, S.R.; Terry, M.A.; Wisniewski, S.R. Development of the Barkin index of maternal functioning. J. Women’s Health 2010, 19, 2239–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkin, J.L.; Wisner, K.L.; Bromberger, J.T.; Beach, S.R.; Wisniewski, S.R. Assessment of functioning in new mothers. J. Women’s Health 2010, 19, 1493–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkin, J.L.; Wisner, K.L.; Wisniewski, S.R. The psychometric properties of the Barkin index of maternal functioning. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2014, 43, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gist, M.E.; Mitchell, T.R. Self-efficacy: A theoretical analysis of its determinants and malleability. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1992, 17, 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, C.M.; Unverzagt, F.W.; Hui, S.L.; Perkins, A.J.; Hendrie, H.C. Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med. Care 2002, 40, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.L.; Holden, J.M.; Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 1987, 150, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QSR International. NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software; QSR International: Doncaster, Australia, 2014; Volume Version 10. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbrother, N.; Young, A.H.; Janssen, P.; Antony, M.M.; Tucker, E. Depression and anxiety during the perinatal period. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’hara, M.W.; Swain, A.M. Rates and risk of postpartum depression—A meta-analysis. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 1996, 8, 37–54.s. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D.; Mannix, J. Giving voice to the burden of blame: A feminist study of mothers’ experiences of mother blaming. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2004, 10, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haga, S.M.; Ulleberg, P.; Slinning, K.; Kraft, P.; Steen, T.B.; Staff, A. A longitudinal study of postpartum depressive symptoms: Multilevel growth curve analyses of emotion regulation strategies, breastfeeding self-efficacy, and social support. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2012, 15, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mahen, H.; Fedock, G.; Henshaw, E.; Himle, J.A.; Forman, J.; Flynn, H.A. Modifying CBT for perinatal depression: What do women want?: A qualitative study. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2012, 19, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelly, J. The Secret to Motherhood? Getting Comfortable with Being Uncomfortable. Available online: http://everydayfamily.com (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- Runquist, J. Persevering through postpartum fatigue. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2007, 36, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, R. Maternal identity and the maternal experience. Ajn Am. J. Nurs. 1984, 84, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockington, I. Postpartum psychiatric disorders. Lancet 2004, 363, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, E.R.; Bergman, N.; Anderson, G.C.; Medley, N. Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akman, I.; Kuşçu, K.; Özdemir, N.; Yurdakul, Z.; Solakoglu, M.; Orhan, L.; Karabekiroglu, A.; Özek, E. Mothers’ postpartum psychological adjustment and infantile colic. Arch. Dis. Child. 2006, 91, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimidjian, S.; Goodman, S.H.; Felder, J.N.; Gallop, R.; Brown, A.P.; Beck, A. Staying well during pregnancy and the postpartum: A pilot randomized trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for the prevention of depressive relapse/recurrence. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 84, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keefe, R.H.; Brownstein-Evans, C.; Rouland Polmanteer, R. “I find peace there”: How faith, church, and spirituality help mothers of colour cope with postpartum depression. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2016, 19, 722–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, L.S.; Curran, L. Maternal identity negotiations among low-income women with symptoms of postpartum depression. Qual. Health Res. 2011, 21, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rich-Edwards, J.W.; Kleinman, K.; Abrams, A.; Harlow, B.L.; McLaughlin, T.J.; Joffe, H.; Gillman, M.W. Sociodemographic predictors of antenatal and postpartum depressive symptoms among women in a medical group practice. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutledge, D.L.; Pridham, K.F. Postpartum mothers’ perceptions of competence for infant care. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 1987, 16, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pridham, K.F.; Chang, A.S.; Mercer, R.T.; Mulvihill, D.L. Mothers′ perceptions of problem-solving competence for infant care. West. J. Nurs. Res. 1991, 13, 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A.M. Transition to motherhood. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2003, 32, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, K.R.; Jones, L.C. Self-esteem, optimism, and postpartum depression. J. Clin. Psychol. 1997, 53, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beebe, B.; Jaffe, J.; Buck, K.; Chen, H.; Cohen, P.; Blatt, S.; Kaminer, T.; Feldstein, S.; Andrews, H. Six-week postpartum maternal self-criticism and dependency and 4-month mother-infant self-and interactive contingencies. Dev. Psychol. 2007, 43, 1360–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pridham, K.F.; Lytton, D.; Chang, A.S.; Rutledge, D. Early postpartum transition: Progress in maternal identity and role attainment. Res. Nurs. Health 1991, 14, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T. Adapting to motherhood: Care in the postnatal period. Community Pract. 2002, 75, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Huff, A.D.; Cotte, J. Complexities of consumption: The case of childcare. J. Consum. Aff. 2013, 47, 72–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negron, R.; Martin, A.; Almog, M.; Balbierz, A.; Howell, E.A. Social support during the postpartum period: mothers’ views on needs, expectations, and mobilization of support. Matern. Child Health J. 2013, 17, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amankwaa, L.C. Postpartum depression among African-American women. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2003, 24, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkin, J.L.; Bloch, J.R.; Hawkins, K.C.; Thomas, T.S. Barriers to optimal social support in the postpartum period. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2014, 43, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorp, S.R.; Krause, E.D.; Cukrowicz, K.C.; Lynch, T.R. Postpartum partner support, demand-withdraw communication, and maternal stress. Psychol. Women Q. 2004, 28, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’hara, M.W.; Stuart, S.; Gorman, L.L.; Wenzel, A. Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2000, 57, 1039–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, A.; Pereira, M.; Araújo-Pedrosa, A.; Gorayeb, R.; Ramos, M.M.; Canavarro, M.C. Be a mom: Formative evaluation of a web-based psychological intervention to prevent postpartum depression. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2018, 25, 473–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell-Carrick, K. Trends in popular parenting books and the need for parental critical thinking. Child Welf. 2006, 85, 819–836. [Google Scholar]

- Bryanton, J.; Beck, C.T.; Montelpare, W. Postnatal parental education for optimizing infant general health and parent-infant relationships. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, N.A.L.; Tam, W.S.W.; Shorey, S. Enhancing first-time parents’ self-efficacy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of universal parent education interventions’ efficacy. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 82, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strange, C.; Fisher, C.; Howat, P.; Wood, L. Fostering supportive community connections through mothers’ groups and playgroups. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 2835–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vejar, C.M.; Madison-Colmore, O.D.; Ter Maat, M.B. Understanding the transition from career to fulltime motherhood: A qualitative study. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 2006, 34, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, D.; Videbech, P.; Hedegaard, M.; Dalby, J.; Secher, N.J. Postpartum depression: Identification of women at risk. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2000, 107, 1210–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pufal-Struzik, I. Self-actualization and other personality dimensions as predictors of mental health of intellectually gifted students. Roeper Rev. 1999, 22, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theall, K.P.; Johnson, C.C. Environmental Influences on Maternal and Child Health; Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute: Basal, Switzerland, 2017; p. 1088. [Google Scholar]

- Barkin, J.L.; Wisner, K.L. The role of maternal self-care in new motherhood. Midwifery 2013, 29, 1050–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, H.P.; Gardiner, A.; Gay, C.; Lee, K.A. Negotiating sleep: A qualitative study of new mothers. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2007, 21, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rychnovsky, J.; Hunter, L.P. The relationship between sleep characteristics and fatigue in healthy postpartum women. Women’s Health Issues 2009, 19, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letourneau, N.L.; Dennis, C.-L.; Benzies, K.; Duffett-Leger, L.; Stewart, M.; Tryphonopoulos, P.D.; Este, D.; Watson, W. Postpartum depression is a family affair: Addressing the impact on mothers, fathers, and children. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 33, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dørheim, S.K.; Bondevik, G.T.; Eberhard-Gran, M.; Bjorvatn, B. Sleep and depression in postpartum women: A population-based study. Sleep 2009, 32, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, S.; Magnuson, S. Motherhood in the 21st century: Implications for counselors. J. Couns. Dev. 2009, 87, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickols, S.Y. From treatise to textbook: A history of writing about household management. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2008, 37, 111–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, M.W.; Rehm, L.P.; Campbell, S.B. Postpartum depression: A role for social network and life stress variables. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1983, 171, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romito, P.; Saurel-Cubizolles, M.-J.; Lelong, N. What makes new mothers unhappy: Psychological distress one year after birth in Italy and France. Soc. Sci. Med. 1999, 49, 1651–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, R.; Johnston, V.; Orr, A. Depression after childbirth: The views of medical students and women compared. Birth 1997, 24, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.N. Functions of support group communication for women with postpartum depression: How support groups silence and encourage voices of motherhood. J. Community Psychol. 2013, 41, 709–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McComish, J.F.; Visger, J.M. Domains of postpartum doula care and maternal responsiveness and competence. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2009, 38, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodou, H.D.; Rodrigues, D.P.; Lima, A.C.M.A.C.; Oriá, M.O.B.; Castro, R.C.M.B.; Queiroz, A.B.A.; Mesquita, N.S.d. Self-Care and empowerment in postpartum: Social representations of puerpera. Int. Arch. Med. 2016, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugha, T.S.; Sharp, H.; Cooper, S.-A.; Weisender, C.; Britto, D.; Shinkwin, R.; Sherrif, T.; Kirwan, P. The Leicester 500 Project. Social support and the development of postnatal depressive symptoms, a prospective cohort survey. Psychol. Med. 1998, 28, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, G.; Kruckman, L. Multi-disciplinary perspectives on post-partum depression: An anthropological critique. Soc. Sci. Med. 1983, 17, 1027–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logsdon, M.C.; Birkimer, J.C.; Barbee, A.P. Social support providers for postpartum women. J. Soc. Behav. Personal. 1997, 12, 89. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, M.J.; Owen, M.T.; Lewis, J.M.; Henderson, V.K. Marriage, adult adjustment, and early parenting. Child Dev. 1989, 60, 1015–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crnic, K.A.; Greenberg, M.T.; Ragozin, A.S.; Robinson, N.M.; Basham, R.B. Effects of stress and social support on mothers and premature and full-term infants. Child Dev. 1983, 54, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levitt, M.J.; Weber, R.A.; Clark, M.C. Social network relationships as sources of maternal support and well-being. Dev. Psychol. 1986, 22, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappuccini, G.; Cochrane, R. Life with the first baby: Women’s satisfaction with the division of roles. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2000, 18, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedder, J.L. Give them the HUG: An innovative approach to helping parents understand the language of their newborn. J. Perinat. Educ. 2008, 17, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Milne, E.; Johnson, S.; Waters, G.; Small, N. Understanding the mother-infant bond. Community Pract. 2018, 91, 45–47. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, P. Opting out?: Why Women Really Quit Careers and Head Home; Univ of California Press: Berkley, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nomaguchi, K.M.; Milkie, M.A.; Bianchi, S.M. Time strains and psychological well-being: Do dual-earner mothers and fathers differ? J. Fam. Issues 2005, 26, 756–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, C.C. Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, C.H.; Chung, H.H. The effects of postpartum stress and social support on postpartum women’s health status. J. Adv. Nurs. 2001, 36, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sink, K.K. Seeking newborn information as a resource for maternal support. J. Perinat. Educ. 2009, 18, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Barkin, J.L.; Jani, S. Information management in new motherhood: Does the internet help or hinder? J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2016, 22, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamerman, S.B.; Kahn, A.J. Home health visiting in Europe. Future Child. 1993, 3, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, R.; Benoit, C.; Van Teijlingen, E.; Wrede, S. Birth by Design: Pregnancy, Maternity Care and Midwifery in North America and Europe; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Segre, L.S.; Stasik, S.M.; O’hara, M.W.; Arndt, S. Listening visits: An evaluation of the effectiveness and acceptability of a home-based depression treatment. Psychother. Res. 2010, 20, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarkka, M.T.; Paunonen, M.; Laippala, P. Social support provided by public health nurses and the coping of first-time mothers with child care. Public Health Nurs. 1999, 16, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Niel, M.S.; Bhatia, R.; Riano, N.S.; de Faria, L.; Catapano-Friedman, L.; Ravven, S.; Weissman, B.; Nzodom, C.; Alexander, A.; Budde, K. The Impact of Paid Maternity Leave on the Mental and Physical Health of Mothers and Children: A Review of the Literature and Policy Implications. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tully, K.P.; Stuebe, A.M.; Verbiest, S.B. The fourth trimester: A critical transition period with unmet maternal health needs. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 217, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.J.; Petrova, M. Prevention science in emerging adulthood: A field coming of age. Prev. Sci. 2019, 20, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (n = 30) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ethnic–Racial Background | n (%) | |

| Asian | 1 (3.3) | |

| Biracial | 1 (3.3) | |

| Black or African American | 10 (33.3) | |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 4 (13.3) | |

| Other | 2 (6.7) | |

| White | 16 (53.3) | |

| Relationship Status | ||

| In a long-term partnership | 28 (93.3) | |

| Single | 2 (6.7) | |

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Bisexual | 3 (10) | |

| Heterosexual | 27 (90) | |

| Partner Gender | ||

| Female | 1 (3.3) | |

| Male | 29 (96.6) | |

| Infant Sex | ||

| Female | 16 (53.3) | |

| Male | 14 (46.7) | |

| Parity | ||

| Primiparous | 17 (56.7) | |

| Multiparous | 13 (43.3) | |

| Religious Identity | ||

| Agnostic | 2 (6.7) | |

| Atheist | 3 (10) | |

| Catholic | 5 (16.7) | |

| Christian | 6 (20) | |

| Jewish | 3 (10) | |

| Muslim | 6 (20) | |

| No religious/spiritual identity | 1 (3.3) | |

| Not affiliated, but religious/spiritual | 4 (13.3) | |

| Education | ||

| 4-year college graduate or Bachelor’s degree | 6 (20) | |

| High school graduate | 5 (16.7) | |

| Master’s Degree | 8 (26.7) | |

| MD/PhD/JD | 3 (10) | |

| Some college | 6 (20) | |

| Employment | ||

| Employed full time (35 h/week or more) | 13 (43.3) | |

| Employed full time but on maternity leave, FMLA | 5 (16.7) | |

| Employed part time (less than 35 h/week) | 2 (6.7) | |

| Full time student | 1 (3.3) | |

| Home maker/stay at home | 3 (10) | |

| Unemployed―looking for work | 6 (20) | |

| Income | ||

| Less than $25,000 | 9 (30) | |

| $25,000–$49,999 | 3 (10) | |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 4 (13.3) | |

| $75,000–$99,999 | 1 (3.3) | |

| $100,000–$124,999 | 2 (6.7) | |

| $125,001–$150,000 | 4 (13.3) | |

| More than $150,000 | 7 (23.3) | |

| M ± SD | Range | |

| Participant age | 30.47 ± 6.01 | 19–41 |

| Relationship length (years) | 6.27 ± 3.9 | 1–15 |

| Number of other children (for multiparous) | 1.46 ± 0.78 | 1–3 |

| Infant age (months) | 5.13 ± 3.77 | 0.5–12 |

| Participants ratings of their mother’s self-efficacy (from 1 poor to 10 very good) | 8.73 ± 2.05 | 3–10 |

| M ± SD | Range | |

| PSS-10 Score1 | 13.37 ± 7.64 | 1–27 |

| BIMF2 | 97.9 ± 10.66 | 70–116 |

| HADS-A3 | 6.73 ± 4.36 | 0–18 |

| HADS-D3 | 3.43 ± 2.92 | 0–10 |

| Factor | n (Mothers Who Discussed Factor) | Supporting Literature | Example Quotes: |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accurate locus of control, limiting inappropriate self-blame | 12 | [24,25] | “And just sort of developmental milestones in your kid, too, and feeling like things are on pace. Because it’s hard to disaggregate what you’re doing from what you’re seeing even though not―not that we’re irrelevant, but not everything that you see in your child is a direct result of things that you’ve done.” |

| Attitude towards learning and adjustment | 28 | [26,27,28,29] | “Knowing that, yeah, I can do this. It’s going to be a pain in the butt. It sounds like a lot of things, but what am I going to do? Never drive in the car with her? It’s something I have to do, so put on your big girl pants and let’s do this.” “Flexibility. It changes almost daily sometimes and you have to be able to go with the flow.” “You might have shitty days, but it gets better.” |

| Bond with baby | 16 | [30,31] | “Some people actually go somewhere else with their baby just to have their one-on-one time. Me, nobody come in my room. Close the door, lock it, and I need some time. I shoo everybody away. Even the phone. I’ll put it on vibrate. I don’t want to hear it ringing, so I can pay attention … My determination to have my bonding time because I feel like babies grow so fast. It’s a month already and it felt like yesterday. I have to be present if I don’t want to miss anything. So I have to learn him, his cues, what faces he make, what they mean. There’s certain cries. He has a certain cry for certain things … I have to learn all this, so I need to pay attention. So I need my time, so I’m determined.” |

| Child temperament | 27 | [32] | “I mean we’ve had I’d say only on three occasions but they were traumatic and embedded in our memory where she cried for like 45 min straight and I mean it’s so wearing. It’s the worst thing … like what you use to torture people.” |

| Emotion regulation | 29 | [33,34] | “I think in preparation for parenthood, I got into mindfulness and meditation, and so that really helped me sort of find space and calmness and ways to just breathe through any stressors or tension, and sort of reassure myself that all the moments are manageable.” |

| Financial and material resources | 21 | [23,35,36] | “I mean, I think the biggest is resources financially and help because it’s like I don’t know how people who don’t have any help or don’t have the financial means to get the help could even attempt to take care of the kids and take care of themselves and the household and if they work … I just think that’s the biggest thing.” |

| Gaining firsthand experience with parenting activities | 24 | [37,38,39] | “Just the experience of taking care of the kids and it comes naturally … each child is different, but you learn more as you work with them.” |

| Giving oneself credit for successes | 16 | [40,41] | “It’s hard for people to give themselves positive feedback. So when I do have a meeting or hangout, so with one or two moms, you don’t hear as many positive statements about, “Oh, I’m doing a great job.” “So give yourself some grace and knowing by yourself that you’re doing a good job, even if you don’t feel it at the time.” |

| Insufficient time for task demands | 26 | [42] | “Lack of time. Trying to pump through times during the day with―we have a very set schedule as a physical therapist. So it’s like you’ll see a patient here, here, and here. You have an hour break, an hour break, and when you’re spending 20 min, there’s no time for that sometimes. And I’m very social, so. I feel like I have to shut myself down sometimes to get everything done.” |

| Internal aspects of engagement with social support | 27 (totals aggregated from subthemes) | ||

| Ability to be vulnerable with social support | 7 | [43] | “Just being really open. Almost grossly open of describing what’s going on with your body and just stuff like that, so... Or being able to open up, just about my self-doubt and those things that I had been feeling that kind of felt dark or they’re not the most pleasant thing to talk to people about, but being able to do that.” |

| Ability to trust others to take care of baby | 15 | [44] | “Having somebody that you trust to leave the baby is very important because then you’re not stressing out the whole time about like, ‘Oh, what the baby is going to do?’ It’s not crying the whole time. So that’s really the most important thing.” |

| Comfort with asking for help and accepting help | 20 | [43,45,46,47] | “Sometimes I don’t reach out when I should and that could probably get in the way. Because then, I have the extra help but then I don’t reach out for it. And then, I start to get frustrated and not being able to take care of myself. And then, the emotions start to come … because sometimes I feel like I can do everything on my own and then I can’t.” |

| Communication skill | 15 | [48,49,50] | “Most definitely communication, because as long as you got somebody next to you and you can communicate, ‘Listen, I need your help because I need to adjust a little bit more. I need you to help me get this schedule together, I need you to help me do this because …’ you just have to talk about it and you have to get it out. You have to.” |

| Recognizing one’s limits and identifying when help is necessary | 16 | [27,39] | “Sometimes you get in your own way by saying I can do everything and then some and then it’s just way too much.” |

| Keeping baby in a routine | 14 | [51] | “I think the knowing that both of my children are content, and we’re prepared for the next day, and knowing that they’re feeling well, and I’m not anticipating disrupted sleep or those sort of things which, I think, I have been able to really establish through a really good routine with them. So I’m able to sort of feel that calm at the end of the day.” |

| Knowledge access | 26 | [52,53,54] | “My working knowledge of being able to take care of my baby, and having the resources if I needed it with lactation or being able to call my pediatrician if anything is wrong. And then also just having my family there as backup just in case. Because they’ve had babies, so they kind of have experience in certain things.” |

| Maintaining aspects of life outside of parenting | 14 | [55,56] | “I would say don’t cancel out all the things that you were doing before because I know you’re busy, and you have a newborn, and you’re trying to focus on it, but try to remember some of the things that you used to like doing before you had the baby. If it’s listening to music or reading a book or something like that because my husband, he literally told me, ‘I wish you would go out with your friends [laughter].’ Because during the nine months, I stayed by myself, and now that I had the baby, I’m still doing it. And he was like, ‘No, it’s not good for you. You need to go out and socialize with people.’ So try not to close off because when you close off from people, you don’t notice it, but your moods change when you get around people.” |

| Mother’s self-knowledge | 20 | [57] | “I guess just knowing yourself too, and knowing what do you need to do to keep yourself mentally in a good place.” |

| Physical home environment | 15 | [58] | “I can say that I have what I have, but it’s not stable. It’s not a stable situation. So it’s like, let’s say―I can be in this situation that I can be kicked out today or tomorrow and I won’t have nowhere. I’ll have to figure that out like fast. And that’s something that I don’t ever want to happen.” |

| Prioritization of self-care | 24 | [59] | “On one side, you feel that it feels good because finally, after a long time, then you’re doing something for yourself, and you know that it’s good for the baby as well because it might help you to get happier and less stressed. And on the other side, then you kind of feel guilty because you’re just taking time away from your baby.” |

| Sleep and fatigue | 22 | [60,61,62,63] | “Energy, which … There’s only so much stamina that one person can sustain, right? Before it’s, you’re just too tired. And I find in life, there aren’t hours to do it. There’s just literally sometimes—a depleted resource or energy. Where you’re just, ‘all I can do is sit on this couch.’ And I feel like there’s so many things I could be doing that are among my life goals, but I just cannot make my brain want to do those things right now.” |

| Social pressures | 18 | [64] | “We just recently, for example, just switched her out of her bassinet. And I didn’t want to talk to anybody about it. Because I felt like we had already left her in there. Our in-laws were complaining that she’s too big for it like a month ago. She’s fine. I think it worked. And then I didn’t want to tell anybody that we were using. I was afraid what they’re going to say.” |

| Strategic planning and time management | 27 | [65] | “I’m also very organized. I mean, I’ve always been a planner, but I would say I’m more so organized now, keeping lists, things like that; things that I need to do on a daily, weekly basis; maintaining schedules for the girls in the morning, afternoon, evening, specifically bedtime now.” |

| Support from others | 30 (totals aggregated from subthemes) | ||

| Emotional support | 28 | [66,67,68,69] | “Yeah. I think someone to talk to is the biggest one. Because I just―I don’t know. I had so many doubts and whether I was doing the right thing or not or trying to figure out the right thing to do for a lot of different scenarios. So yeah, just helped me to be able to talk about that to somebody.” |

| Encouragement of mother’s self-care by social support | 15 | [70,71] | “Getting out. Going to a yoga class once a week. I would just come home a totally different person. I’m very frugal and I don’t spend money on those things and my husband was like, “You need to go to that every week. You just come home refreshed … it’s good for you.” |

| Engaged social network | 26 | [45,72] | “My mom. She’s just a helpful person. And she has six grandkids so she’s just like, ‘Oh, do you need any help? I’m coming over. I’m going to help you do this,’ I’m like, ‘Okay.’ I’m like, ‘That is fine.’ I’m like, ‘I don’t get to worry about all this alone anymore.’ And she just helped me out. She’s a big help.” |

| Hands on support with childcare and home management | 30 | [45,66,73] | “In my opinion, the most important thing is other human resources. So whether it’s a partner or someone else who’s available to do those things. Because if you can’t have someone else taking care of your child, you can’t do anything separate from your child to take care of yourself. So I think that’s huge, and just from some talks to other moms, people who are really struggling, it often seems like that was the tension. Like a partner who works a lot, or family that is far away … no matter how capable you are, at some point you just can’t, and you need someone else to change a diaper or get up in the middle of the night, feed a bottle. You just can’t … And people who don’t have as much of that really end up at their wits’ end.” |

| Partner-specific support | 18 | [74,75,76,77,78] | “For me, it’s just that my partner is just awesome, and he’s just super supportive … So, yeah. He knows that we’re a team, and he’s very appreciative of the parent that I am and everything.” |

| Taking breaks and getting out of the house | 24 | [73] | “My mother-in-law takes the baby in the morning and then I get her back at 12:00 noon, then she’s happy, she’s fed, she’s changed and she took a good nap too. So then when she comes back, she’s all good and I’m able to have that time with her where I’m not like, ‘Oh, why don’t you go to sleep? I fed you an hour ago and now, you want me to feed you again’, and stuff like that.” |

| Understanding baby | 25 | [79,80] | “I know when he’s tired. I know when he’s mean. I know when he don’t want to be bothered. I just know. I know my son. My daughter will tell me in a minute that there’s nothing wrong with her, but I know when something’s wrong with her. So I know my children very well. That’s why I communicate with them in the way that I do.” |

| Workplace flexibility and understanding | 23 | [81,82,83] | “So I think on the work side, it’s very important to have an environment that is supportive. So your boss and the organization you’re working for, being supported is very important. Because in the beginning, you’re just trying to figure out this new motherhood thing, so―having somebody that supports you really helps you, not just practically but also psychologically.” |

| “Internal” Factors, Best Addressed by Intervening on the Mother | “External” Factors, Best Addressed by Intervening on the System Surrounding the Mother |

|---|---|

Mental Health Counseling:

| Encouragement of Mother’s Personal Social Support Network, Connecting Mother to Other Sources of Support (e.g., mom’s groups), Advocacy:

|

| Encouragement and Education of Mother About the Importance of Self-Care: | |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Formal Educational Resources and/or Training: | |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Albanese, A.M.; Geller, P.A.; Steinkamp, J.M.; Barkin, J.L. In Their Own Words: A Qualitative Investigation of the Factors Influencing Maternal Postpartum Functioning in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176021

Albanese AM, Geller PA, Steinkamp JM, Barkin JL. In Their Own Words: A Qualitative Investigation of the Factors Influencing Maternal Postpartum Functioning in the United States. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(17):6021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176021

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlbanese, Ariana M., Pamela A. Geller, Jackson M. Steinkamp, and Jennifer L. Barkin. 2020. "In Their Own Words: A Qualitative Investigation of the Factors Influencing Maternal Postpartum Functioning in the United States" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 17: 6021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176021

APA StyleAlbanese, A. M., Geller, P. A., Steinkamp, J. M., & Barkin, J. L. (2020). In Their Own Words: A Qualitative Investigation of the Factors Influencing Maternal Postpartum Functioning in the United States. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176021