Context Matters: Findings from a Qualitative Study Exploring Service and Place Factors Influencing the Recruitment and Retention of Allied Health Professionals in Rural Australian Public Health Services

Abstract

1. Introduction

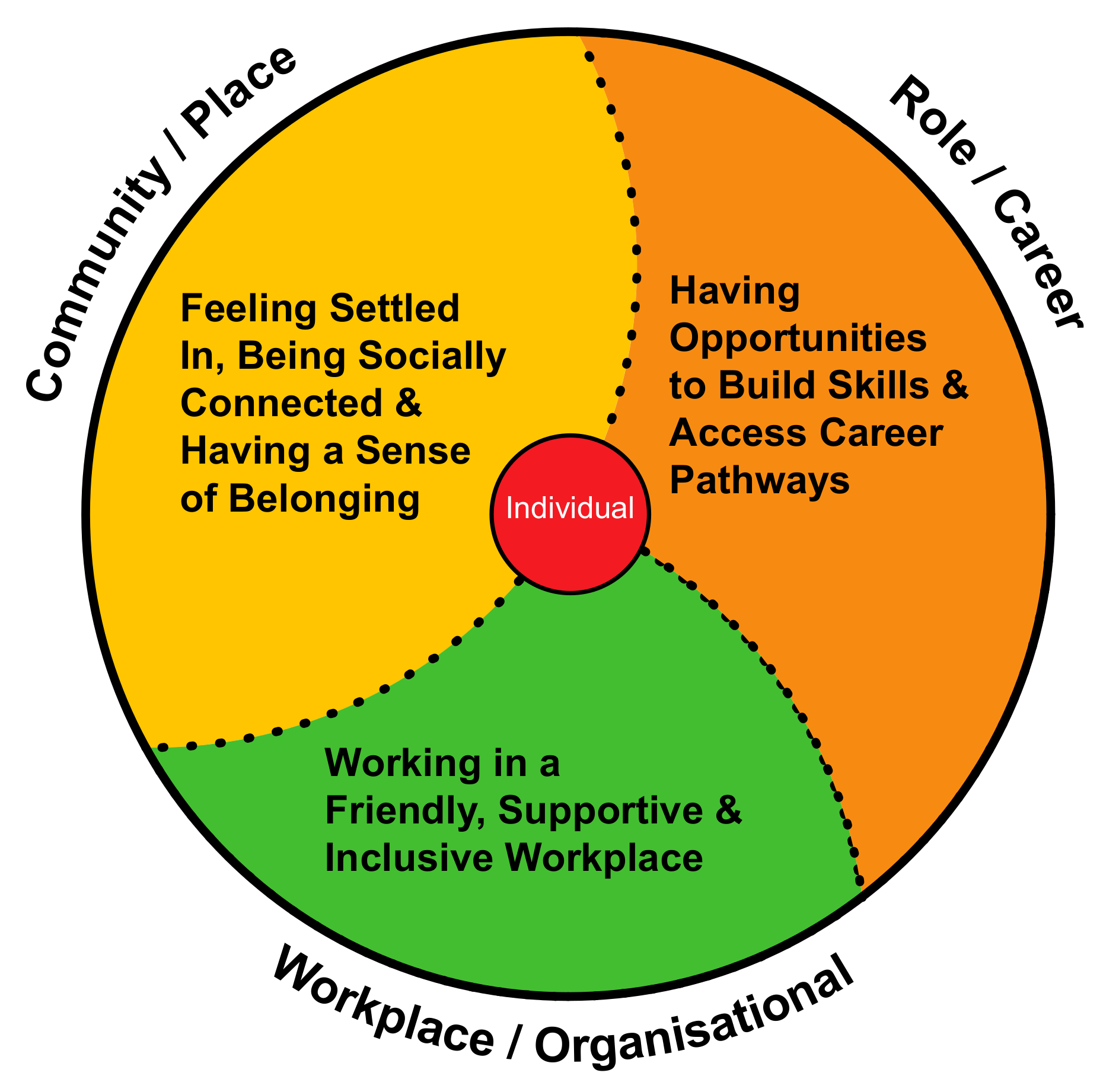

Guiding Theoretical Framework

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aims

- How do AH staff working in rural public health services perceive their current work and personal experience as influencing job retention?

- What are the service and place-specific challenges and opportunities facing rural public health services in achieving a sustainable AH workforce?

2.2. Design

2.3. Participants

2.4. Recruitment

2.5. Interview Data Collection

2.6. Interview Data Analysis

2.7. Rigour

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Participants

3.2. Workplace

3.2.1. Degree of Challenge: Attracting, Recruiting, and Retaining Allied Health Professionals (AHPs) Varies Depending on Profession, Experience Level and Life Stage

So, I commute every day [it’s] one hour and 20 [drive] to here. Yeah, I do 240kms a day when I work here. I only work here three days a week now.ReHS-TAHS-6

I know I can keep my staff for 12 months. I can do that. I’ve got systems in place that they’re that busy and they’re that well-nourished and they’re that supported that 12 months is easy. 12–24 months, it’s gets a bit more tenuous.ReHS-KI-4

The benefit of them being here in terms of skills development are huge in the first year, probably pretty solid in the second year, I don’t know what they would gain in clinical advantage being here after two years, so …that third year would really be more for the community’s benefit than for them … they’d need social reasons to stick around.RuHS-KI-6

The single thing that will bring it all down, is the social side.ReHS-KI-4

It’s ongoing. There seems to always be a constant flow of vacancies but not for the wrong reasons, it’s … that younger group heading off overseas … heading off to the next opportunity.ReHS-KI-10

I think one of our big recruitment areas is the Grade 2s in our community teams—getting someone who’s mid-career to come here for that next step in their career.ReHS-KI-8

When you are mid-career, when you’ve hit a Grade 2 level, you usually have been working for a little while, you’ve sort of set your group somewhere. You’re not necessarily going to up and shift … you might shift for a partner, but you won’t necessarily shift for a job.ReHS-KI-3

The partners aren’t interested in coming up to X [town’s name], it’s not geographically a big enough drawcard that they could envisage themselves living up here.ReHS-KI-4

I’m Grade 2, so if you want to retain that next level of workers—kind of the middle seniority—you have to give them permanent hours … because it’s just too difficult to be going from contract to contract.ReHS-KI-5

On the contract, on the letter, they already say they are going to supply eight weeks of free accommodations. …[The offer of accommodation was] very important, probably the most important fact, because like for me, because I’m living in Melbourne… it is actually impossible for me to get any accommodation because I don’t want to get accommodation I haven’t seen before I rent it. So, it’s very important for that … accommodation.RuHS-TAHS-13

The hospital provided it [accommodation]. They’ve got quite a few houses around that they lease off landlords or whatever and then they charge people to come in. But they provided accommodation for X weeks free, no bills, no nothing. I thought that was magnificent, that was a really attractive thing coming down here…free accommodation and really good accommodation too.RuHS-TAHS-7

[We are] turning over positions every six months. By the time they’re orientated and can start being useful, they’re actually leaving. So, it’s not a good result for the community and it’s not a good result for us financially either, having to run and educate and it’s demoralising for other staff to have to orientate and onboard, and at some stage you get fatigued with that.RuHS-KI-4

3.2.2. Allied Health (AH) Managers Usually Recruited from Existing Workforce and Poorly Prepared for Leadership

I’ve been told by a few others that I have a softer style that helps to try and nurture and bring people along—not as direct as some might be. So, having that open-door policy and so forth to make sure that they’re comfortable, they can come and talk at any time. So, it’s about being open, being honest with them, answering their questions, helping to guide and support them.ReHS-KI-10

My manager creates the environment and I feel like… she’s the very key reason the staff that I work with are here and a very key reason for why I love to work here.ReHS-TAHS-6

Everything [staff member’s name] says she wants, I never got at her stage, so I don’t know what it looks like. I’ve never had a mentor. I’ve never been supervised.RuHS-TAHS-3

From workforce perspective that was a concern … I had people that were being remunerated as seniors that weren’t necessarily acting or taking responsibility of seniors, not all of them.ReHS-KI-2

You don’t go to uni to learn to be a manager, you go to uni to learn to be a clinician, the rest is on the job.ReHS-KI-10

I think for early leaders it’s a real challenge… that’s hard and that’s where I think [name of service] is off track it needs to support those new emerging leaders as they come into those roles.ReHS-KI-10

3.3. Organisational

Overly Complex Human Resources Systems Negatively Impact Successful AHP Recruitment and are Burdensome for AH Managers

Our HR department seems under resourced. The responsiveness to getting our staff on board, they’re off accepting another opportunity before [HR have] managed to complete an onboarding or even to get to onboarding. It’s a challenge, 2–3 weeks to get back to someone to say ‘Yeah, you’ve been through all those processes and you are now successful’. That’s a long time.ReHS-KI-10

We have major issues with HR … It’s killing us … So, the guy that was due to start today … he still didn’t have a contract 10 days beforehand and I recruited him six weeks ago. And [so] you lose them. I just wonder if he had had a contract and signed it whether he would have felt committed?ReHS-KI-15

I understand there was a bit of a HR block here. So the HR process took a long time to come through … Maybe I interviewed in early Feb then, because I remember starting on the [late date in] March … as that was as soon as HR could onboard me … So I remember like it made me doubt myself … and I thought how could I have not gotten this job?ReHS-TAHS-10

My recruitment efforts have been enormous but for every recruitment, the amount of time I have spent riding HR to get things through has meant there’s 10 other things I’m not getting done.ReHS-KI-15

I think reducing the stress and burnout on the senior clinicians. There’s some teams at the moment where I think the stress levels of the senior clinicians is not a great environment for the new grads to be in at all.ReHS-KI-8

3.4. Role

3.4.1. Most Entry-Level AH Staff Experience a Challenging Adjustment

So, the X [name of the clinical team] area is incredibly fast paced and busy and there isn’t a lot of time to think, prepare, discuss. It’s bang, bang, bang, and bang. … Absolutely [it’s a] ‘do’ job, [there’s] very little time. The culture is reflected in that, that everybody’s very efficient and busy and quick and there’s not a lot of sort of chatting.ReHS-TAHS-7

I got to the point after three months where I was booking in, probably overbooking a little bit, because I’m like, ‘Oh, the wait list is huge, I’m going to try and get through, try and get through it’. And then things would pop up on the IPU (inpatient unit) that were urgent, and I was getting quite stressed because I couldn’t fit everything into the day.RuHS-TAHS-4

Anything I need, anything I have to run by them, they make the time for me and X [name of manager] really gives me a lot of confidence in my abilities. She’s like, ‘Why are you worrying about this? It’s exactly what I would have done.’ ‘Of course, you’re on the right track.’ ‘If you forgot to ask a question [to a patient], you can go back and see them, tomorrow, can’t you?’ or ‘It’s just no fuss.’ I’m stressing about these things that I was made to stress about on placement which I don’t ever stress about here, it’s completely different.RuHS-TAHS-9

[Early career is] not really easy. I personally don’t advise new grads to work in rural anymore. I think they need support and no matter how much promise they get, I got a lot of promises but I didn’t get a lot of support.RuHS-TAHS-1

[It’s] the best team. … so approachable [and] non-judgemental, because I come up with some stupid questions sometimes. But [they’re] just very, very supportive. Willing to go the extra mile, to kind of make you feel comfy or address any issues or whatever. If you’re like, ‘Oh, could I talk to you about this?’ They’ll go, ‘No, no sit down, what’s happening?’ … My manager creates the environment and I feel like … she sets the culture.ReHS-TAHS-6

Well, there’s a bit, maybe bullying might be the wrong word, like it’s not as strong. But I just feel like the people who have been here a lot longer, when there’s new people who come, the expectations they have of them are very high … When they’re … doing that same shift, they … expect that newer persons to have done all those things … [that] they themselves they don’t usually do.ReHS-TAHS-24

3.4.2. Professional Development Opportunities Are a High Priority for AHPs and the Level and Type of Support Offered Is not Always Well Understood by AH Staff or Consistently Implemented by AH Managers

I had a little bit of interest in learning [a particular discipline-specific approach] … and it’s something you [the service] might offer in the future, but probably not anytime soon. But I wanted to do it for my own sort of learning and interest. And work was supportive of me taking the time off for leave and paid for the course as well, which I really didn’t expect. Which was really nice, and the course was run over a Friday and then a Saturday morning and they offered either time in lieu or to be paid for the Saturday morning as well, which I didn’t expect. Because I was happy just to, so yeah, they were very, very, very supportive.RuHS-TAHS-4

One of the things that I thought was really important for me when I wanted to come and work here was about the opportunity for professional development and ongoing learning … That’s really important to me. I don’t know, we’re all learning people, that’s why we go into this lifestyle and X [health service’s name] have been really good.RuHS-TAHS-8

I came from X [another rural service’s name] and you got $250 a year [for external CPD], that was it. And here we’re paying thousands and they’re going off to all sorts of things and even for locums. [In my head] I’m going, ‘Oh my god’, but I haven’t [changed anything yet]. I’d like a framework so that I can be transparent in decision making and equitable [regarding funding for external courses]. So, if you can produce one of those that would be fantastic.RuHS-KI-2

There’s no [financial support for PD], you just get the leave … And it wasn’t made clear [during recruitment]. I only found out from someone here who said, ‘[It’s] in the EBA that there’s no money’.ReHS-TAHS-36

Yeah, good training opportunities, quick training opportunities, you’re able to get training quickly here as in compared to bigger metropolitan cities [where] it takes a while.ReHS-TAHS-35

We have a budget. My budget’s $500 for the year for the whole team … What I do is, I say to them, ‘I’m very supportive of professional development, you tell me what you want to go to, and if you will be prepared to pay for it [up front, then] we’ll apply for a scholarship through RWAV [Rural Workforce Agency Victoria], and that’s usually not knocked back and the organisation pays for the days.ReHS-KI-3

Many years ago, the hospital funded lots of stuff and it was fantastic, and it was a great drawcard and it was really good. It was like, ‘Yeah, we’ll fund you for a course a year maybe’. They’ve pulled all that back.ReHS-KI-4

I think, recruitment wise, focusing on how we market that [PD support] and what incentives we offer to people at that stage of their life to be taking that next career step here.ReHS-KI-8

3.5. Career

Limited Career Development/Advancement Opportunities for AHPs Working in Rural Services

There’s two opportunities [at the moment] but then if they … get two people and they are [then] here for 30 years, you’re going to be stuck as a Grade 1 for 30 years.ReHS-TAHS-24

There’s not much movement within organisations as well, particularly when it’s a smaller organisation. It makes it harder because there’s not as much growth usually.ReHS-TAHS-1

If there were the opportunities to step up, yeah absolutely [I’d stay]. If there’s not, then I’ll leave.RuHS-TAHS-5

When it comes to retaining them, well I think we have touched on it, in regard to the opportunities that they have to grow and develop.ReHS-KI-10

3.6. Place

Securing Suitable Housing is a Priority Issue for all AHPs Relocating for Work

I didn’t realise how hard it was going to be for them to get housing and, in hindsight, I probably should have.MN ReHS-KI-4

Everyone was very supportive, and you know [saying], ‘I’ve got spare room’. They were [saying], ‘You’re not going to be homeless, so don’t worry’.RuHS-TAHS-4

I just couldn’t find anything. I just thought, ‘I can’t find anything that fits the bill’, and it didn’t matter how many properties people threw under my nose … then it was around Christmas time and Christmas was impossible to find anything. No one will take you on inspections. And trying to find inspections that were on after hours was really difficult. All the real estate agents shut, they open at 8.30, they shut at 5pm. My working hours are anywhere between 7 and 5, so it’s just, it was impossible to even to get to a real estate office to say, ‘I’m looking for a property, I want some support’ … I’d have friends going to inspections for me.ReHS-TAHS-10

I had [housing] options in place before I moved … She [her manager] sent an email around, you know, around and then just said, ‘these are all the potentials’. I think there were about six different contact numbers of people to [share with]. That made things so much easier … a lot easier not having to come and try and then find things on my own.ReHS-TAHS-1

3.7. Community

3.7.1. Establishing Social Connections, Particularly in the Workplace, is a Priority Issue for Almost all AHPs Relocating for Work

Pretty much from the first day, for the first week, I felt included like that. Everyone in, particularly in this area, is incredibly welcoming, really amazingly so.RuHS-TAHS-6

[In the] X [profession name] team I felt really welcomed. As soon as I got here, they made sure I was okay, got to know me, had a welcome dinner. Y [staff member’s name] organises all of the social events for X and that was a good opportunity to get to know them outside of work, you talk about different things.ReHS-TAHS-9

I would love to be closer and I have close bonds with people [here] but there is still the [distance] barrier that separates you from developing … things further. And a lot of other people are not from here, so they’re most likely to go back home [straight after work] anyway. But everyone’s from different directions and some people have kids and it just gets really messy [trying to catch-up out of work].ReHS-TAHS-6

There was a couple of people there who just weren’t interested in any of the regional stuff, unless it was open after hours on a Monday to Thursday because ‘we’ll only be here for one year and we’ll be going to Melbourne every Friday night and coming back on Monday morning’.ReHS-KI-8

I don’t have friends here and I’ve sort of grown distant from my friends from uni. So that’s, like it does impact a lot that I don’t have friends, I don’t have, like, a social life … I do wish there were more opportunities to make friends and more sort of social events, which there’s definitely a lack of in X [town’s name].ReHS-TAHS-24

Moving back to a small town I thought that I’d know everyone. I don’t know anyone there either… they’ve all moved away.ReHS-TAHS-22

3.7.2. Linking into Local Activities is of Importance for Many AHPs Relocating for Work

The social activities are quite underground in [town’s name] and so there’s a whole lot of things going on but there’s never any communication about it or even being sort of asked.ReHS-KI-2

I think my main, I guess, outlook for finding friends has been through work and then through the tennis club and then if you know someone and they bring someone new along then.ReHS-TAHS-9

To be honest, no [not interested in participating in social activities in town], because I’m sort of moving from that social young stage into the settling down, sort of maybe getting married stage. But to be honest, and I’m not a super social person, I’m pretty slack, I’m a bit of homebody as well.ReHS-TAHS-8

They’re fine, they’re nice [other team members], I just, I don’t go out … Yeah see [if] I go out, I don’t drink, I’m Muslim, most of the food they have I can’t have, as [it’s not] halal. It’s not that I don’t make friends here, I’ve got friends here, but I just don’t socialise. Out of hours I don’t socialise that much.ReHS-TAHS-35

I think in the country towns is if you’re not sort of in the football, netball, then it’s harder I suppose to make those connections outside of work and get to know the people.ReHS-TAHS-19

I was made aware of a local running group … I eventually made contact with one of the people and he said, ‘Yeah. Come along, get involved.’ I thought it would be good to get involved in that … I’ll give it go…I quite enjoyed it, but … they didn’t tend to come up to me and say: ‘I’m such and such, how you going? What you been doing etc., etc.?’ There wasn’t a lot of that. I haven’t been back.RuHS-TAHS-7

4. Discussion

4.1. Review of Findings

4.2. Analysis of Recommendations

4.2.1. Organisational/Workplace Domain

4.2.2. Role/Career Domain

4.2.3. Place/Community Domain

4.3. Broader Relevance of the Recommendations

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Rural & Remote Health—Web Report. 2019 v16.0. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/rural-health/rural-remote-health/contents/rural-health (accessed on 20 July 2019).

- Ducat, W.; Burge, V.; Kumar, S. Barriers to, and enablers of, participation in the allied health rural and Remote Training and Support (AHRRTS) program for rural and remote allied health workers: A qualitative descriptive study. BMC Med. Educ. 2014, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Callaghan, A.M.; McAllister, L.; Wilson, L. Barriers to accessing rural paediatric speech pathology services: Health care consumers’ perspectives. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2005, 13, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, J. Review of Australian Government Health Workforce Programs; Department of Health and Ageing: Canberra, Australia, 2013.

- Commonwealth Department of Health. National Health Workforce Data Set—Allied Health Factsheets 2017; Commonwealth Department of Health: Canberra, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm, M.; Russell, D.; Humphreys, J. Measuring rural allied health workforce turnover and retention: What are the patterns, determinants and costs? Aust. J. Rural. Health 2011, 19, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, N.; McAllister, L.; Eley, D. The influence of motivation in recruitment and retention of rural and remote allied health professionals: A literature review. Rural. Remote. Health 2012, 12, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government Productivity Commission. Australia’s Health Workforce: Productivity Commission Research Report; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, T.N.; Cooper, R.; Brown, L.J.; Hemmings, R.; Greaves, J. Profile of the rural allied health workforce in Northern New South Wales and comparison with previous studies. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2008, 16, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, E.; D’Amore, W.; McMeeken, J. Physiotherapy in rural and regional Australia. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2007, 15, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Rural Health Commissioner. Discussion Paper for Consultation: Rural Allied Health Quality, Access and Distribution. Options for Commonwealth Government Policy Reform and Investment; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2019.

- Malatzky, C.; Cosgrave, C.; Gillespie, J. The utility of conceptualisations of place and belonging in workforce retention: A proposal for future rural health research. Health Place 2020, 62, 102279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, D.; Farmer, J.; Carulla, L.S.E.; Dalton, H.; Luscombe, G.M. The Orange Declaration on rural and remote mental health. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2019, 27, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrave, C. The whole-of-person retention improvement framework: A guide for addressing health workforce challenges in the rural context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrave, C.; Hussain, R.; Maple, M. Retention challenge facing Australia’s rural community mental health services: Service managers’ perspectives. Aust. J. Rural Health 2015, 23, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Lynham, S.; Guba, E. Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences, revisited. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N., Lincoln, Y., Eds.; SAGE Publications Inc: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 97–128. [Google Scholar]

- Terry, G.; Hayfield, N.; Clarke, V.; Braun, V.; Willig, C.; Rogers, W.S. Thematic analysis. SAGE Handb. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2017, 12, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, S.; Lincoln, M.; Smith, T. Retention of allied health professionals in rural New South Wales: A thematic analysis of focus group discussions. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Tian, E.J.; May, E.; Crouch, R.; McCulloch, M. You get exposed to a wider range of things and it can be challenging but very exciting at the same time: Enablers of and barriers to transition to rural practice by allied health professionals in Australia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, S. Perceptions of occupational therapists practising in rural Australia: A graduate perspective. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2006, 53, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakerman, J.; Humphreys, J.; Russell, D.J.; Guthridge, S.; Bourke, L.; Dunbar, T.; Zhao, Y.; Ramjan, M.; Murakami-Gold, L.; Jones, M.P. Remote health workforce turnover and retention: What are the policy and practice priorities? Hum. Resour. Health 2019, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onnis, L.A. Human resource management policy choices, management practices and health workforce sustainability: Remote Australian perspectives. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2017, 57, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millsteed, J. Factors affecting the retention of occupational therapists in rural services. Occup. Ther. Health Care 2002, 14, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagnitti, K.; Reid, A.; Dunbar, J. Short report: Retention of allied health professionals in south-west of Victoria. Aust. J. Rural Health 2005, 13, 364–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, J.N.; Still, M.; Stewart, K.; Croaker, J. Recruitment and retention issues for occupational therapists in mental health: Balancing the pull and the push. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2010, 57, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillham, S.; Ristevski, E. Where do I go from here: We’ve got enough seniors? Aust. J. Rural. Health 2007, 15, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, K.; Schoo, A.; Stagnitti, K.; Cuss, K. Rethinking policies for the retention of allied health professionals in rural areas: A social relations approach. Health Policy 2008, 87, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosgrave, C.; Malatzky, C.; Gillespie, J. Social determinants of rural health workforce retention: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosgrave, C.; Maple, M.; Hussain, R. An explanation of turnover intention among early-career nursing and allied health professionals working in rural and remote Australia—Findings from a grounded theory study. Rural. Remote. Health 2018, 18, 4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, N.; Eley, D.; McAllister, L. How do allied health professionals construe the role of the remote workforce? New insight into their recruitment and retention. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillespie, J.; Redivo, R. Personal-professional boundary issues in the satisfaction of rural clinicians recruited from within the community: Findings from an exploratory study. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2012, 20, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta-Briand, B.; Coleman, M.; Ledingham, R.; Moore, S.; Wright, H.M.; Oldham, D.; Playford, D. Understanding the factors influencing junior doctors’ career decision-making to address rural workforce issues: Testing a conceptual framework. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, J.S.; Wakerman, J.; Wells, R. What do we mean by sustainable rural health services? Implications for rural health research. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2006, 14, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakerman, J.; Humphreys, J.S. “Better health in the bush”: Why we urgently need a national rural and remote health strategy. Med. J. Aust. 2019, 210, 202–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Increasing Access to Health Workers in Remote and Rural Areas Through Improved Retention: Global Policy Recommendations; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Buykx, P.; Humphreys, J.; Wakerman, J.; Pashen, D. Systematic review of effective retention incentives for health workers in rural and remote areas: Towards evidence-based policy. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2010, 18, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albion, M.J.; Fogarty, G.J.; Machin, M.; Patrick, J. Predicting absenteeism and turnover intentions in the health professions. Aust. Health Rev. 2008, 32, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathman, D.E.; Konrad, T.; Dann, R.; Koch, G. Retention of primary care physicians in rural health professional shortage areas. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 1723–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniels, Z.M.; Vanleit, B.J.; Skipper, B.J.; Sanders, M.L.; Rhyne, R.L. Factors in recruiting and retaining health professionals for rural practice. J. Rural. Health 2007, 23, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, M.; Perkins, D.; Kumar, K.; Roberts, C.; Moore, M. What factors in rural and remote extended clinical placements may contribute to preparedness for practice from the perspective of students and clinicians? Med. Teach. 2013, 35, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, L.L.; Santos, L.M.P.; Santos, W.; Oliveira, A.; Rattner, D. Mais Médicos program: Provision of medical doctors in rural, remote and socially vulnerable areas of Brazil, 2013-2014. Rural. Remote. Health 2016, 16, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Van Essen, C.; Steffes, B.C.; Thelander, K.; Akinyi, B.; Li, H.-F.; Tarpley, M.J. Increasing and retaining African surgeons working in rural hospitals: An analysis of PAACS surgeons with twenty-year program follow-up. World J. Surg. 2018, 43, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Migration of Health Workers: The WHO Code of Practice and The Global Economic Crisis; WHO Document Production Services: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cortez, L.R.; Guerra, E.C.; Da Silveira, N.J.D.; Noro, L.R.A. The retention of physicians to primary health care in Brazil: Motivation and limitations from a qualitative perspective. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| WoP-RIF Domains | Major Influence on Job/Personal Satisfaction |

|---|---|

| Workplace | High-quality workplace relationships with line manager and in team |

| Organisational | Organisation managed efficiently and strategically |

| Role | Opportunities to engage with other discipline-specific health professionals and governing bodies |

| Career | Opportunities for career development/advancement |

| Place | Experience a sense of belonging in place |

| Community | Community involved in the planning and implementation of recruitment and retention strategies |

| AH Profession/Position Type | Regional Health Service | Rural Health Service | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. Target AH Staff Participants | |||

| Allied health assistance | 4 | - | 4 |

| Dentistry | NA | 2 | 2 |

| Dietetics | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Exercise physiology | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Medical laboratory science | 2 | - | 2 |

| Diagnostic imaging medical physics | 9 | 1 | 10 |

| Occupational therapy | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Podiatry | 2 | 2 | |

| Pharmacy | 2 | - | 2 |

| Physiotherapy | 9 | 2 | 11 |

| Psychology | 1 | - | 1 |

| Social work | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Speech pathology | 2 | - | 2 |

| 37 | 14 | 51 | |

| Key Informant Participants | |||

| Executive | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| AH managers | 10 | 3 | 13 |

| Other health managers | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| AH locums | 4 | - | 4 |

| 16 | 7 | 23 | |

| All participants | 53 | 21 | 74 |

| WoP-RiF Domains | Key Identified Themes | Key Elements |

|---|---|---|

| Workplace | Degree of challenge attracting, recruiting, and retaining AHPs varies depending on profession, experience level and life stage |

|

| AH managers usually recruited from existing workforce and poorly prepared for leadership |

| |

| Organisational | Overly complex human resources systems negatively impact successful AH recruitment and burdensome for AH managers |

|

| Role | Most entry-level AH staff experience a challenging adjustment |

|

| Professional development opportunities are a high priority for AHPs and the level and type of support offered is not always well understood by AH staff or consistently implemented by AH managers |

| |

| Career | Limited career development/advancement opportunities for AHPs working in rural services |

|

| Place | Securing suitable housing is a priority issue for all AHPs relocating for work |

|

| Community | Establishing social connections, particularly in the workplace, is a priority issue for nearly all AHPs relocating for work |

|

| Linking into local activities is of importance for many AHPs relocating for work |

|

| WoP-RiF Domains | Key Themes Identified | Study Recommendations | WHO Recommendations [35] | Buykx et al. Recommendations [36] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organisational | Degree of challenge attracting, recruiting, and retaining AHPs varies depending on profession, experience level and life stage |

| Make it worthwhile to move to a remote or rural area Pay attention to living conditions | Maintaining realistic and competitive remuneration—packaging benefits Providing appropriate and adequate infrastructure—adequate housing Maintaining adequate and stable staffing |

| Overly complex human resources systems negatively impact successful AH recruitment and burdensome for AH managers |

| Ensure the workplace is up to an acceptable standard | Fostering an effective and sustainable workplace organisation | |

| Workplace | AH managers usually recruited from existing workforce and poorly prepared for leadership |

| Maintaining adequate and stable staffing | |

| Role | Most entry-level AH staff experience a challenging adjustment |

| Facilitate professional development | Shaping the professional environment that recognises and rewards individuals making a significant contribution to patient care |

| Professional development (PD) opportunities are a high priority for AHPs and the level and type of support offered is not always well understood by AH staff or consistently implemented by AH managers |

| |||

| Career | Limited career development/advancement opportunities for AHPs working in rural services |

| Design career ladders for rural health workers | |

| Place | Securing suitable housing is a priority issue for all AHPs relocating for work |

| Pay attention to living conditions | Ensuring social, family and community support |

| Community | Establishing social connections, particularly in the workplace, is a priority issue for almost all AHPs relocating for work |

| NA | |

| Linking into local activities is of importance for many AHPs relocating for work |

| NA |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cosgrave, C. Context Matters: Findings from a Qualitative Study Exploring Service and Place Factors Influencing the Recruitment and Retention of Allied Health Professionals in Rural Australian Public Health Services. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5815. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165815

Cosgrave C. Context Matters: Findings from a Qualitative Study Exploring Service and Place Factors Influencing the Recruitment and Retention of Allied Health Professionals in Rural Australian Public Health Services. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(16):5815. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165815

Chicago/Turabian StyleCosgrave, Catherine. 2020. "Context Matters: Findings from a Qualitative Study Exploring Service and Place Factors Influencing the Recruitment and Retention of Allied Health Professionals in Rural Australian Public Health Services" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 16: 5815. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165815

APA StyleCosgrave, C. (2020). Context Matters: Findings from a Qualitative Study Exploring Service and Place Factors Influencing the Recruitment and Retention of Allied Health Professionals in Rural Australian Public Health Services. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5815. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165815