How Does COVID-19 Pandemic Influence the Sense of Belonging and Decision-Making Process of Nursing Students: The Study of Nursing Students’ Experiences

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.2. Purpose of the Study

2. Methods

2.1. Theoretical Framework: Social Cognitive Career Theory

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Human Subject Protection

3. Results and Findings

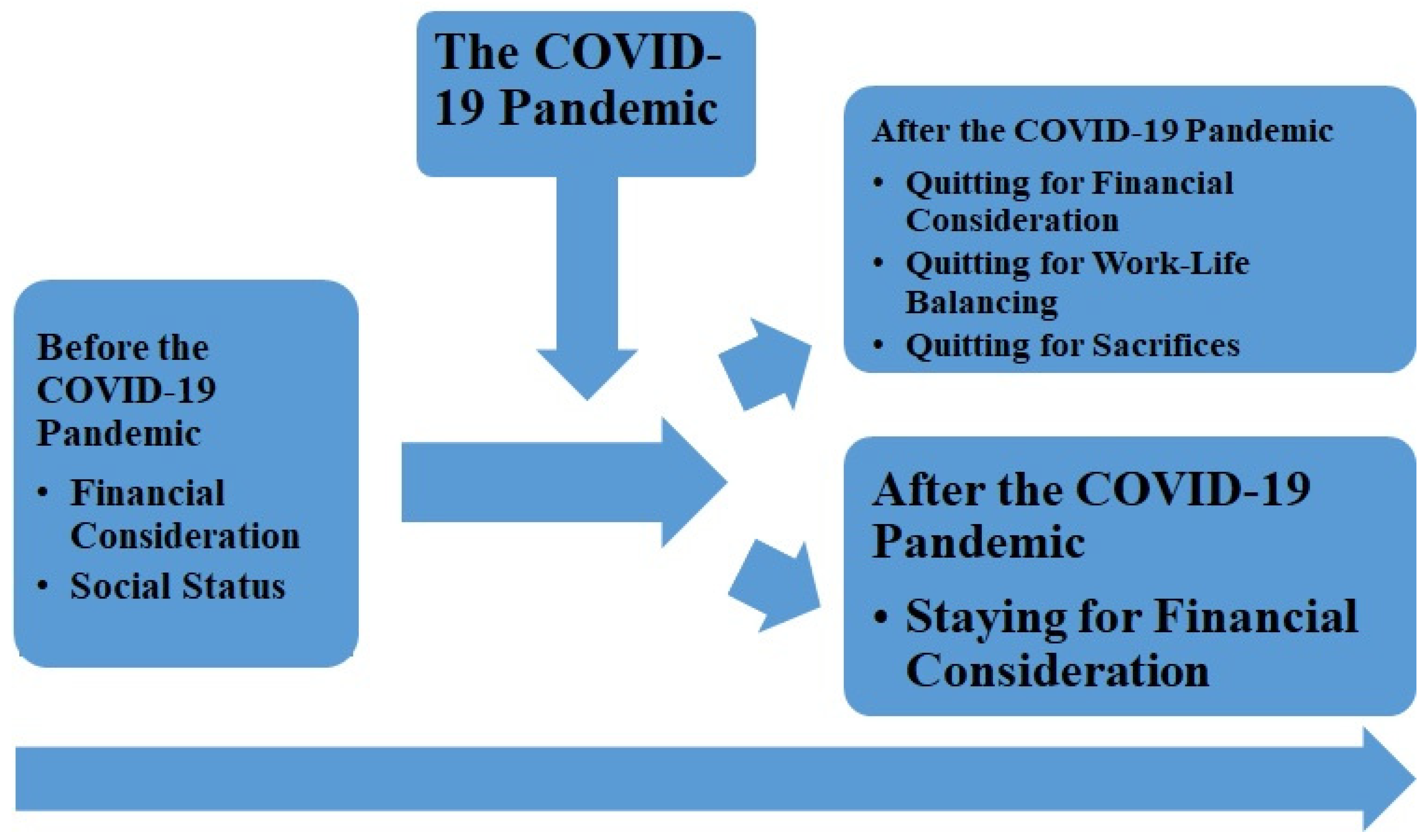

3.1. Before the COVID-19 Pandemic: Financial Consideration as the Major Goal because I Am a Money Person

I have no personal achievements … no interests … no goals … no career interests … based on my grades. I wanted to study a major that offered a career with a better salary and benefits … [W]orking in a hospital, especially a large-sized hospital in Seoul, is a way of making money … [T]his is the only reason why I wanted to study nursing … [M]oney was the biggest reason …(P#42)

I could have selected biology or nursing as my major(s) during high school … I selected nursing because nurses can make more money…I wanted to learn biology as it was my interest … but all I need is money and a salary … I would never pick a major that could not produce money …(P#53, Sophomore)

To be honest, I do not want to be a nurse…but I want to receive a nurse’s salary … I do not really care about the treatment of the patients … I care about myself … I care about money and the holidays … I do not have any dreams … this is Korea … I just care about myself and my money…(P#54)

3.1.1. Making More Money for Personal Reasons

I can earn a lot of money because I will be working as a nurse in a large hospital … I want to buy a lot of handbags and cosmetic items and a luxury car, and I want to change my cell phone every season … I cannot afford this lifestyle at the moment as I am not rich enough … but once I can earn money as a nurse … I can do something that can satisfy my lifestyle …(P#22)

I love up-to-date cell phones and computers…at the moment, I do not want to buy any outdated models … I need to change my electronic items each season…I want to become a nurse … [I]t is totally about money…I do not care about the patients … [A]ll I need is the money … I am not an angel or whatever, I am a money girl.(P#34)

I can have long holidays and a good salary to pay for my holidays … I plan to have a working holiday after I have worked in a hospital for one or two years … I do not care about how society and communities see me … I have my own life, and my life is about making money with my nursing licence.(P#12)

3.1.2. Making More Money for Better Family Life

… [M]aking money is my goal … I don’t care about my patients or my career development … [B]eing a nurse is all about money for my marriage … I want to make more money to buy a house after my marriage … [N]ursing is a good way for girls to make money …(P#3)

… [N]ursing is one of the best occupations to make money…especially for girls in Korea … I want to buy a house for my parents … I will send money to my younger brothers for university … I picked this major because as a girl … I need to find a way to make money … I was thinking about a career in finance … but only a nursing school accepted my application … [I]t is all about money…(P#25)

... I have a plan with my father already … [A]fter I have gained several years of experience and saved enough money in Seoul … we can invest in a private clinic in the rural community … I already have a plan and timetable … I want to be a boss … I do not want to work for someone … I want to manage the bookkeeping instead of nursing … [M]edical services can be a business …(P#47)

3.2. Before the COVID-19 Pandemic: Climbing the Social Ladder

3.2.1. Medical and Nursing as Some of the Highest Occupations in South Korea

I want to reach the upper level of society with my nursing degree and job … I don’t like nursing and I don’t like caring for patients … but I like the social status … perhaps … because many Korean people believe nurses are upper-level individuals in the society … I want to become one of the highest people in the community … again, I do not like patient caring … I like social level and money …(P#33)

… I study nursing only because I want to build up to the upper level … I really hate caring for patients … I will tell my supervisor I am a lazy girl … but society needs me as the there is a shortage of nurses … I can find jobs pretty easily … [A]s a registered nurse, I have an advantage in society … I can gain jobs that I like …(P#32)

… I don’t care about my working environment … I care about how my nursing degree will help me gain a job with less responsibilities … I know nursing is not an easy profession … but I can adjust my workload…I am not here to care for patients … I only want a job so that I can engage in my hobbies and interests after working hours and for the social status I will have as a nurse …(P#41)

…I want use my occupation as a nurse as a way to marry a rich organizational leader, as nurses are sexy and attract rich men in the business field … [P]erhaps I can marry a doctor or hospital leader … I don’t want to work as a nurse once I am married … [M]y purpose in choosing to study nursing and enter the profession is to make money … I am not here to care for patients. I am here for the money and social status …(P#38)

3.3. During the COVID-10 Pandemic: Quitting or Staying in the Professional Due to Financial and Work-Life Balance Considerations

3.3.1. Staying in the Profession for Financial and Business Networking Purposes: COVID-19 as a Provider of Business Opportunities

I need to make more money, so I need to become a nurse. Although I really don’t like patient caring … I need to make more money for my dream traveling … and perhaps handbags and some leisure activities … I just hate patient caring and I hate taking care of people …(P#25)

Korean people like nurses … because they are working in higher status workplaces … such as hospitals … I like this prestige … [I]t is my first priority … in seeking to become a nurse … [I]t is not about the patients …(P#49)

I decided to study nursing because I want to make more money and I want to save more money for traveling and shopping … for handbags and leisure activities … The COVID-19 pandemic will not change my mind about this money-making decision … I still want to make money from the medical field … I will start my own clinic … It should be a way to make money …(P#50)

… I am sure I will not leave the medical profession … I will use this opportunity to make more money from patients … I have a business mind with a nursing focus … I will enter a hospital … to understand how it operates and patients’ behaviors … [A]fter gaining several years’ experience … I will start my own clinic…but again, I need to make money … [T]he COVID-19 pandemic will not change my focus on money …(P#11)

3.3.2. The Insignificant Salary and Benefits in the Nursing Profession Do Not Match the Sacrifice

… I joined the nursing profession because of the salary. I do not have money to start my clinic in the future…I have to work in a hospital to finance my leisure activities and handbags … Although the salary is very attractive, I have to work for more than 10 h a day … but I do not receive any additional payments even when I work overtime…I disagree with this situation …(P#16)

… [M]y hobby is not nursing, caring for patients, or working for society … [M]y hobbies are buying handbags…watching movies … going to a coffee shop and chatting with my friends … [D]ue to this COVID-19 pandemic, many medical professionals need to work overtime with no additional salary … [If] I cannot go to buy a handbag after I finish work, I will not join this profession …(P#39)

My goal is to become a sexy nurse K-pop star who can make a lot of money on the stage, TV shows, and movies … [D]on’t you think the gimmick of sexy nurse and K-pop is more attractive than a fat nurse working in a hospital for 30 years? … I want to work in a plastic surgery clinic in the future because I want to take advantage of the free plastic surgery … but for now, I will just follow the K-pop direction after my graduation…(P#51)

I was planning to work just in surgery before I left the hospital … but I don’t think that will work after the COVID-19 pandemic … [M]any hospitals and medical organizations have changed their benefit packages … no more plastic surgery benefits for staff with less than five years’ working experience … I may enter the business industry, for example, promotion or TV show work, with my professional nursing skills.(P#2)

I am planning to work as a leader or join a leadership team … I do not want to help any patients as I want to lead people and make more money with my skills … Since the COVID-19 pandemic, I have changed my mind somehow … I will not join the nursing profession … [I]nstead, I want to use my nursing and medical skills to start a YouTube channel for health promotion …(P#44)

I am sure that I am not going to touch those people who are infected with this international virus … I disagree with how the government treats nursing professionals … [W]e are human and we have family members … [W]hy would the government send us to the frontline for the patients? I want to make money and manage people …(P#33)

… [I]n the first place, I do not have a strong interest in nursing, but I am interested in money, my name, a good position, and a good company … [C]aring for patients and older people is of no interest to me … [A]fter this COVID-19 pandemic, I do not think I will join the nursing profession as I really don’t want to provide care to older people …(P#21)

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Developments

5. Conclusions

Practice Implications

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Name | Years at University | University Location | Career Decision after the COVID-19 Pandemic |

|---|---|---|---|

| P#1 | Freshmen (1st Year) | Seoul | Will not enter the nursing profession after university graduation |

| P#2 | |||

| P#3 | |||

| P#4 | |||

| P#5 | |||

| P#6 | Busan | ||

| P#7 | |||

| P#8 | Daejeon | ||

| P#9 | |||

| P#10 | |||

| P#11 | Sophomore (2nd Year) | Seoul | |

| P#12 | |||

| P#13 | |||

| P#14 | |||

| P#15 | |||

| P#16 | |||

| P#17 | Gangwon-do | ||

| P#18 | |||

| P#19 | Gyeonggi-do | ||

| P#20 | |||

| P#21 | Daejeon | ||

| P#22 | |||

| P#23 | |||

| P#24 | |||

| P#25 | |||

| P#26 | Junior (3rd Year) | Seoul | |

| P#27 | |||

| P#28 | |||

| P#29 | Jeolla-do | ||

| P#30 | |||

| P#31 | |||

| P#32 | Gyeongsang-do | ||

| P#33 | |||

| P#34 | |||

| P#35 | Daegu | ||

| P#36 | |||

| P#37 | |||

| P#38 | |||

| P#39 | Senior (4th Year) | Seoul | |

| P#40 | |||

| P#41 | |||

| P#42 | |||

| P#43 | |||

| P#44 | Gwangju | ||

| P#45 | |||

| P#46 | |||

| P#47 | Incheon | ||

| P#48 | |||

| P#49 | |||

| P#50 | Daejeon | ||

| P#51 | |||

| P#52 | Ulsan | ||

| P#53 | |||

| P#54 | Busan | ||

| P#55 | |||

| P#56 | |||

| P#57 | Stay in the nursing professional after university graduation | ||

| P#58 |

Appendix B

- (1)

- Was nursing your first choice for university major? Can you tell me more about your selection procedure?

- (2)

- Why do you want to become a nursing student? What are your motivations? Can you tell me more with examples?

- (3)

- Do you want to become a nurse or medical professional in the medical field? Why or why not?

- (4)

- If you have a chance again, do you want to study nursing as your university major? Why or why not?

- (5)

- Did you change your mind about being a nursing student during the COVID-19 Pandemic? How?

- (6)

- How would you describe your experiences, sense of belonging, and career decision-making process due to the COVID-19 Pandemic?

- (7)

- Do you still want to become a nurse after the COVID-19 Pandemic? Why or why not?

- (8)

- What motivations or reasons have been changed after the COVID-19 Pandemic? In any directions, can you tell me more?

References

- Johnson, W.G.; Butler, R.; Harootunian, G.; Wilson, B.; Linan, M. Registered Nurses: The Curious Case of a Persistent Shortage. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2016, 48, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jones, M. Career Commitment of Nurse Faculty. Res. Theory Nurs. Pract. 2017, 31, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raymond, A.; James, A.; Jacob, E.; Lyons, J. Influence of perceptions and stereotypes of the nursing role on career choice in secondary students: A regional perspective. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 62, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, M.R.; da Silva, V.M.; Guedes, N.G.; de Oliveira Lopes, M.V. Clinical validation of the “eedentary lifestyle” nursing diagnosis in secondary school students. J. Sch. Nurs. 2016, 32, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dabney, B.W.; Linton, M.; Koonmen, J. School nurses and RN to BSN nursing students. NASN Sch. Nurse 2017, 32, 30–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dos Santos, L.M. I am a nursing student but hate nursing: The East Asian perspectives between social expectation and social context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilson, B.L.; Butler, M.J.; Butler, R.J.; Johnson, W.G. Nursing Gender Pay Differentials in the New Millennium. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2018, 50, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.; Bovin, J. Accelerate Your Career in Nursing: Nurse’s Guide to Professional Advancement and Recognition; Sigma Theta Tau International: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1937554583. [Google Scholar]

- White, E.M.; Aiken, L.H.; Sloane, D.M.; McHugh, M.D. Nursing home work environment, care quality, registered nurse burnout and job dissatisfaction. Geriatr. Nurs. (Minneap) 2020, 41, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, E.; Vehkakoski, T.; Aunola, K.; Määttä, S.; Kairaluoma, L.; Pirttimaa, R. Motivational sources of practical nursing students at risk of dropping out from vocational education and training. Nord. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2019, 9, 112–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, G.A.; Fitzgerald, L. A clinical internship model for the nurse practitioner programme. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2008, 8, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roso-Bas, F.; Pades Jiménez, A.; García-Buades, E. Emotional variables, dropout and academic performance in Spanish nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 37, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainbow, J.G.; Steege, L.M. Transition to practice experiences of first- and second-career nurses: A mixed-methods study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 1193–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.-Y.; Tang, F.-I.; Chen, I.-J.; Yin, T.J.C.; Chen, C.-C.; Yu, S. Nurse administrators’ intentions and considerations in recruiting inactive nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M. A Comparison of Asian American, Caucasian American, and Chinese College Students: An Initial Report. J. Multicult. Couns. Dev. 2002, 30, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.M. Rural Public Health Workforce Training and Development: The Performance of an Undergraduate Internship Programme in a Rural Hospital and Healthcare Centre. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Creswell, J. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation; Jossey Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sharan, B.; Merriam, E.J.T. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation, 4th ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, K.H.; Dos Santos, L.M. A brief discussion and application of interpretative phenomenological analysis in the field of health science and public health. Int. J. Learn. Dev. 2017, 7, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Connelly, F.M.; Clandinin, D.J. Stories of experience and narrative inquiry. Educ. Res. 1990, 19, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clandnin, D.; Connelly, F. Narrative Inquiry: Experience and Story in Qualitative Research; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, N.-Y.; Lin, I.-H.; Huang, Y.-T.; Chen, M.-H.; Lu, W.-H.; Yen, C.-F. Associations of Perceived Socially Unfavorable Attitudes toward Homosexuality and Same-Sex Marriage with Suicidal Ideation in Taiwanese People before and after Same-Sex Marriage Referendums. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dos Santos, L.M. Recruitment and retention of international school teachers in remote archipelagic countries: The Fiji experience. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dos Santos, L.M.; Lo, H.F. The development of doctoral degree curriculum in England: Perspectives from professional doctoral degree graduates. Int. J. Educ. Policy Leadersh. 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.M. Reforms of engineering education programmes: Social Cognitive Career Influences of engineering students. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2019, 14, 4698–4702. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D.R. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boblin, S.L.; Ireland, S.; Kirkpatrick, H.; Robertson, K. Using Stake’s Qualitative Case Study Approach to Explore Implementation of Evidence-Based Practice. Qual. Health Res. 2013, 23, 1267–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D.; Hackett, G. Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. J. Vocat. Behav. 1994, 45, 79–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.M. How do teachers make sense of peer observation professional development in an urban school. Int. Educ. Stud. 2016, 10, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.M. Foreign Language Teachers’ Professional Development through Peer Observation Programme. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2016, 9, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.D.; Lent, R.W. Social Cognitive Career Theory at 25: Progress in Studying the Domain Satisfaction and Career Self-Management Models. J. Career Assess. 2019, 27, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.D.; Lent, R.W. Social cognitive career theory in a diverse world. J. Career Assess. 2017, 25, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, R.L.; Flores, L.Y.; Worthington, R.L. Mexican American middle school students’ goal intentions in mathematics and science: A test of social cognitive career theory. J. Couns. Psychol. 2007, 54, 320–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.M. Career decision of recent first-generation postsecondary graduates at a metropolitan region in Canada: A social cognitive career theory approach. Alberta J. Educ. Res. 2018, 64, 141–152. [Google Scholar]

- Lent, R.W.; Lopez, A.M.; Lopez, F.G.; Sheu, H.-B. Social cognitive career theory and the prediction of interests and choice goals in the computing disciplines. J. Vocat. Behav. 2008, 73, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.M. International school science teachers’ development and decisions under social cognitive career theory. Glob. J. Eng. Educ. 2020, 22, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Mendez, S.; Martin Conley, V.; Keith, R.; Haynes, C.; Gerhardt, R. Mentorship in the engineering professoriate: Exploring the role of social cognitive career theory. Int. J. Mentorol. Coach. Educ. 2017, 6, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.M. Postgraduate international students’ living and learning experience at a public university in British Columbia. Alberta J. Educ. Res. 2018, 64, 318–321. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos, L.M. The relationship between personal beliefs and teaching practice of ESL teachers at an Asian community centre in Vancouver: A qualitative research in progress. Alberta J. Educ. Res. 2017, 63, 98–101. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Applications of Case Study Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas, C. Phenomenological Research Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D. Social cognitive career theory at 25: Empirical status of the interest, choice, and performance models. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 115, 103316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, M.M.; Shoffner, M.F. Perspective First-Generation College Students: Meeting Their Needs Through Social Cognitive Career Theory. Prof. Sch. Couns. 2004, 8, 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, M.N.; Dahling, J.J.; Chin, M.Y.; Melloy, R.C. Integrating Job Loss, Unemployment, and Reemployment with Social Cognitive Career Theory. J. Career Assess. 2017, 25, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, L.Y.; O’Brien, K.M. The career development of Mexican American adolescent women: A test of social cognitive career theory. J. Couns. Psychol. 2002, 49, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D. Social cognitive career theory and subjective well-being in the context of work. J. Career Assess. 2008, 16, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D. Social cognitive approach to career development: An overview. Career Dev. Q. 1996, 44, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.M. Exploring international school teachers and school professional staff’s social cognitive career perspective of life-long career development: A Hong Kong study. J. Educ. e-Learn. Res. 2020, 7, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.M. Promoting safer sexual behaviours by employing social cognitive theory among gay university students: A pilot study of a peer modelling programme. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dos Santos, L.M. The motivation and experience of distance learning engineering programmes students: A study of non-traditional, returning, evening, and adult students. Int. J. Educ. Pract. 2020, 8, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.M. Stress, burnout, and turnover issues of Black expatriate education professionals in South Korea: Social biases, discrimination, and workplace bullying. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.M. The challenges of public health, social work, and psychological counselling services in South Korea: The issues of limited support and resource. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCarty M, H.A. Moving to an all graduate profession: Preparing preceptors for their role. Nurse Educ. Today 2003, 23, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, V.A.; Lambert, C.E.; Itano, J.; Inouye, J.; Kim, S.; Kuniviktikul, W.; Sitthimongkol, Y.; Pongthavornkamol, K.; Gasemgitvattana, S.; Ito, M. Cross-cultural comparison of workplace stressors, ways of coping and demographic characteristics as predictors of physical and mental health among hospital nurses in Japan, Thailand, South Korea and the USA (Hawaii). Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2004, 41, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.-Y. To have or to be? Narrating Confucian value in contemporary Korea. Int. Commun. Chin. Cult. 2016, 3, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Park, H. Perceived gender discrimination, belief in a just world, self-esteem, and depression in Korean working women: A moderated mediation model. Womens Stud. Int. Forum 2018, 69, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, G.-W.; Choi, J.N.; Moon, R.J. Skilled Migrants as Human and Social Capital in Korea. Asian Surv. 2019, 59, 673–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWhirter, E.H.; Crothers, M.; Rasheed, S. The effects of high school career education on social-cognitive variables. J. Couns. Psychol. 2000, 47, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.A.; Kim, H.; Lee, K.-W. Perceptions of determinants of job selection in the hospitality and tourism industry: The case of Korean university students. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 16, 422–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-Y.; Shin, Y.-C.; Oh, K.-S.; Shin, D.-W.; Lim, W.-J.; Cho, S.J.; Jeon, S.-W. Association between work stress and risk of suicidal ideation: A cohort study among Korean employees examining gender and age differences. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2020, 46, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nantsupawat, A.; Kunaviktikul, W.; Nantsupawat, R.; Wichaikhum, O.; Thienthong, H.; Poghosyan, L. Effects of nurse work environment on job dissatisfaction, burnout, intention to leave. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2017, 64, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricketts, T.C. The changing nature of rural health care. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2000, 21, 639–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hama, T.; Takai, Y.; Noguchi-Watanabe, M.; Yamahana, R.; Igarashi, A.; Yamamoto-Mitani, N. Clinical practice and work-related burden among second career nurses: A cross-sectional survey. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.M. I teach nursing as a male nursing educator: The East Asian perspective, context, and social cognitive career experiences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Reich, M. Medical Education in East Asia: Past and Future; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, E.R.; McKenna, L.; D’Amore, A. Educators’ expectations of roles, employability and career pathways of registered and enrolled nurses in Australia. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2016, 16, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Del Prato, D.M. Transforming Nursing Education: Fostering Student Development towards Self-Authorship. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. Scholarsh. 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, E.J.M.; Verhaegh, K.J.; Kox, J.H.A.M.; van der Beek, A.J.; Boot, C.R.L.; Roelofs, P.D.D.M.; Francke, A.L. Late dropout from nursing education: An interview study of nursing students’ experiences and reasons. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2019, 39, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Glew, P.J.; Hillege, S.P.; Salamonson, Y.; Dixon, K.; Good, A.; Lombardo, L. Predictive validity of the post-enrolment English language assessment tool for commencing undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2015, 35, 1142–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y. Becoming researchers: A narrative study of Chinese university EFL teachers’ research practice and their professional identity construction. Lang. Teach. Res. 2014, 18, 242–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, H.; Mackenzie Davey, K. Teaching for life? Midlife narratives from female classroom teachers who considered leaving the profession. Br. J. Guid. Counc. 2011, 39, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tyson, R. Pedagogical imagination and practical wisdom: The role of success-narratives in teacher education and professional development. Reflect. Pract. 2016, 17, 456–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dos Santos, L.M. English language learning for engineering students: Application of a visual-only video teaching strategy. Glob. J. Eng. Educ. 2019, 21, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos, L.M. Science lessons for non-science university undergraduate students: An application of visual-only video teaching strategy. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2019, 14, 308–311. [Google Scholar]

- Skelton, C. Male Primary Teachers and Perceptions of Masculinity. Educ. Rev. 2003, 55, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottingham, M.D. The missing and needed male nurse: Discursive hybridization in professional nursing texts. Gender Work Organ. 2019, 26, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Themes and Subthemes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Section 3.1 | Before the COVID-19 Pandemic: Financial Consideration as the Major Goal because I am a Money Person | |

| Section 3.1.1 | Making more Money for Personal Reasons | |

| Section 3.1.2 | Making more Money for Better Family Life | |

| Section 3.2 | Before the COVID-19 Pandemic: Climbing the Social Ladder | |

| Section 3.2.1 | Medical and Nursing as Some of the Highest Occupations in South Korea | |

| Section 3.3 | During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Quitting or Staying in the Profession due to Financial and Work-Life Balance Considerations | |

| Section 3.3.1 | Staying in the Profession for Financial and Business Networking Purposes: COVID-19 as a Provider of Business Opportunities | |

| Section 3.3.2 | The Insignificant Salary and Benefits in the Nursing Profession do not Match the Sacrifice | |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dos Santos, L.M. How Does COVID-19 Pandemic Influence the Sense of Belonging and Decision-Making Process of Nursing Students: The Study of Nursing Students’ Experiences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5603. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155603

Dos Santos LM. How Does COVID-19 Pandemic Influence the Sense of Belonging and Decision-Making Process of Nursing Students: The Study of Nursing Students’ Experiences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(15):5603. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155603

Chicago/Turabian StyleDos Santos, Luis Miguel. 2020. "How Does COVID-19 Pandemic Influence the Sense of Belonging and Decision-Making Process of Nursing Students: The Study of Nursing Students’ Experiences" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 15: 5603. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155603