Women’s Views of and Responses to Maternity Services Rendered during Labor and Childbirth in Maternity Units in a Semi-Rural District in South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Sampling and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

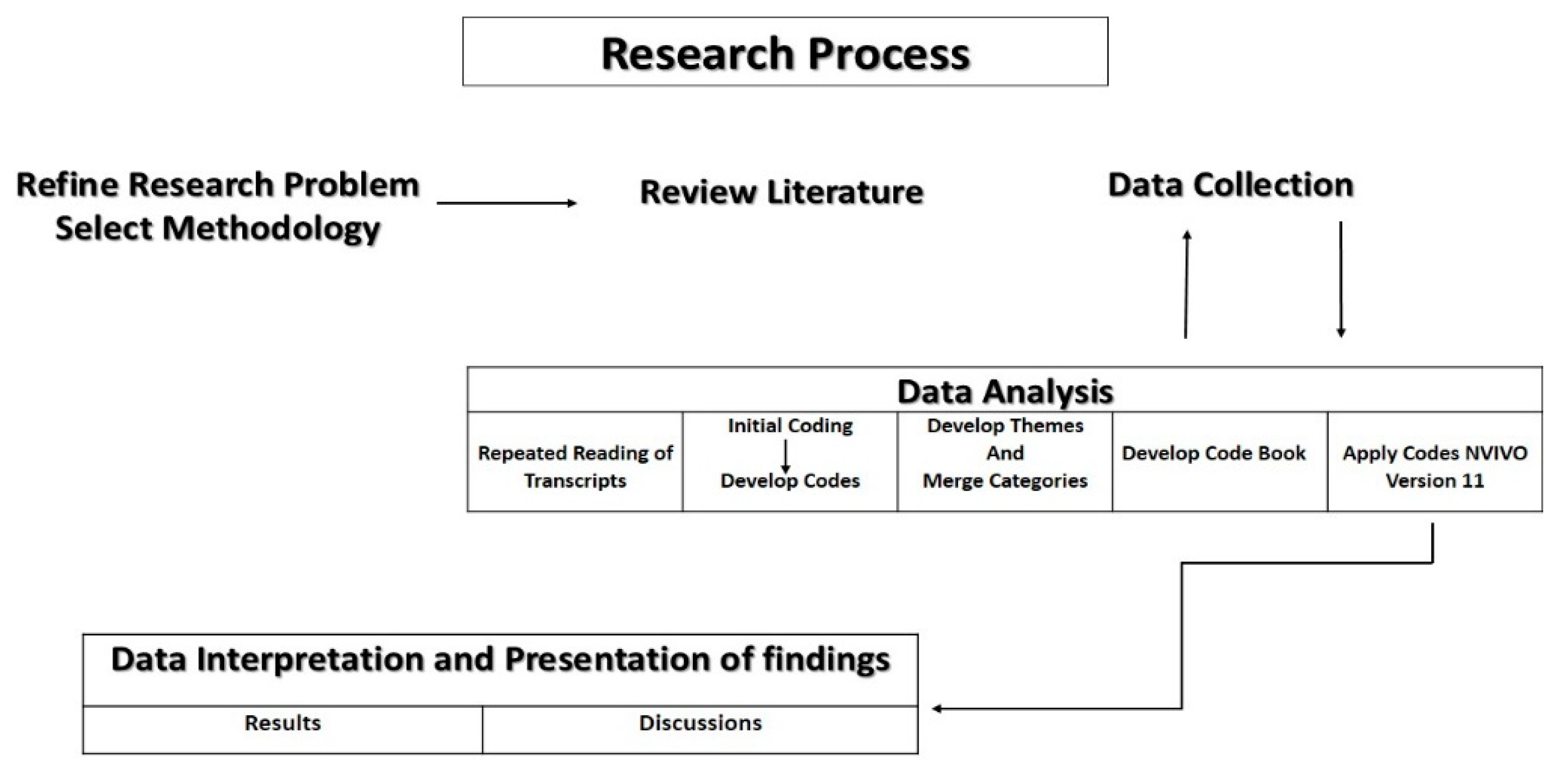

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Themes

3.2. Midwife/Patient Interactions

“She was helpful, and she was sweet. She was not pushy, she was not shouting, she was talking to me in a good way” (Otsile, 24 years, para1).

“… She told me that I was three centimeters dilated and she told me that I may go back to sleep because that blood was not a problem” (Lebo, 23 years, para 1).

“I was afraid to talk to her in the beginning, but I saw that she was good to me, so I started to be open for her as well … The communication was good, she was ever smiling,… encouraging me, saying you will finish, after the baby comes there will no longer have any pain” (Maggy, 22 years, para 2).

“… I think if you cooperate and then they talk to you politely then I think you will also not become harsh, but if someone talks to you in a harsh manner, you will also start telling them off” (Roro, 29 years, para 3).

“I did my homework and found that it depends on how you are. I think if you are uncooperative you will get bad service, like if you are cheeky and you want to do things in your own way. I think they also get frustrated to a point that they would think that, this one wants to annoy us” (Rose, 27 years, para 2).

3.3. Verbal Abuse and Disrespectful Care

“My complaint is that I was scolded like a small child just for asking them to put the baby on my chest, I just wanted that bond with my baby … From there while they were busy suturing me they were shouting at me because my legs were shaking” (Caro, 30 years, para 1).

“I think that some of the questions are not any of their business. Hei! Why do you give birth to so many children? Is it the same father? Is he going to take care of the baby? Is he working? I don’t like such thing” (Roro, 29 years old, para 3).

“… You should endure whatever they do to you. You must endure. Whatever they say, I must just keep quiet. So that at the end I should get help. Because if you answer them they will tell you, Yaa! On top of that you have a big mouth; we will leave you just there” (Johanna, 30 years, para 2).

“They said pull that dustbin near you and vomit inside … it is not the one that you put normal waste in. So then I am inhaling the smell, the smell that comes from those things …” (Johanna, 30 years, para 2).

“Yoo! It is dirty, it is dirty, yoo! It is disgusting…. that place hai! Hai! Hai! There are toilets that are not working, it is smelly. It is not a conducive place to be used by pregnant women to bath, because even those who just gave birth they bath there, jaa…. And then the dishes that we use to bath are also not enough for everyone … There is no way that you can use the bath tub, it is dirty…” (Puleng, 20 years, para 1).

“…there are a lot of cockroaches, they were crawling on top of us, I don’t know why the cleaners are not cleaning …” (Julia, 24 years, para 2).

“… the bed that I was sleeping on the linen also had blood … No the blood was not mine, when I entered in the room I found blood … like felt bad and I asked myself that but why did they not at least change the sheet?” (Lebogang, 22 years, para 1).

3.4. Neglect and Abandonment during Labor

“The baby was just going to come without anyone there. They were at the reception and I was in the room, which was closed with a curtain … I shouted, I must shout and said nurse! It is not good …” (Ncinah, 25 years, para 2).

“I called them from the chairs… Immediately after I climb on top of the bed I gave birth, and even then I had to also call them, they were not coming to examine me” (Kgantshi, 24 years, para 2).

“… but the other thing that I think was not right is that they leave us for a long time. They should come and check on us frequently …” (Roro, 29 years, para 3).

“Hai, Ok, but there was this other lady who gave birth on the floor… So she was coming back from the toilet, then she started screaming saying the baby’s head is coming out, Then the nurses went to her, and said hold it. They were supporting her so that she can go to her room, then the baby fell on the ground. That happened In front of the whole group of women” (Otsile, 24 years, para 1).

“So after that I pushed and delivered. I told her that … I am feeling dizzy. From there I did not see what happened. I just found myself on the floor. Then my front tooth broke” (Puleng, 20 years, para 1).

“… when I arrived she showed me the room and then she continued with her sleep. I came in at about twelve at night and then at about half past one my water broke. That is when she came to help me at half past one…. That is when she examined me, since I came in at twelve …. If I did not knock on her door, she would not have thought of waking up” (Lebo, 23 years, para 1).

“.. Not that she should babysit me, just at least so that you can feel that she is next to you… Why should they sleep for about three to four hours and remember it is at night … since they checked me at about 12 until at 5 in the morning” (Milly, 28 years, para2).

“When I arrived they made me wait there for a long time.… I arrived at about 6 in the morning and at about 8 o’clock it was when they came to admit me and I had labor pain all along… They sat me at the benches there, there was nothing happening, they just left me there …” (Kgantshi, 24 years, para 2).

“Yes, you sit at the benches… when you come in and the beds are full, and you are having labor pain, you must wait for the other to finish first…” (Maggy, 22 years, para 2).

“We were so many on that day, like a lot, so we were sitting in the passage of the labor ward … That was the only place that had some space, because the labor ward was so full that day… but when the labor pain started to escalate, I was still at the chairs and it was getting late and I still did not have a bed at all…” (Otsile, 24 years, para 1).

3.5. Information Sharing

“No, you see those who helped me with my first labor, they were good. They were able to tell me that you are these centimeters dilated, and they would even show me the chart that, you see you get the baby when you are this far… That gave me the hope that at least the baby is on the way. Can you imagine when someone checks you and after that they don’t tell you how far you are, they just say you are fine. So you just don’t know what is happening in your process of labor” (Milly, 28 years, para 2).

“…Just to explain to you to show that this is your file. They don’t explain that as you are having high blood pressure this is what it means, no they are just busy writing … and you don’t even know what they are writing” (Noma, 27 years, para 2).

“They gave me an injection, and they also gave me certain two big pills, but they did not tell me what they were for… It makes me feel bad … I asked myself that, is my baby not fine or is there something wrong with me? It would have been better if they explained to me” (Lizzy, 37 years, para 3).

3.6. Response to Care Received

3.7. Fear and Uncertainty

“I could not understand. I was afraid. I wished to get out of that bed and run out of the facility and deliver at home…” (Caro, 30 years, para, 1).

“I was afraid, I don’t want to lie, because I felt like if I ask her questions, she will answer me in a rude manner because of she will be feeling sleepy… Maybe I would have lost my baby I don’t know...” (Tshego, 23 years, para 2).

3.8. Panic and Anxiety

“Here! You are spoiled; your mind is corrupted, yes… When I had my first baby, eei…! I was, I was, you know, I ended up seeing things, things which are not there [visual hallucinations] and I also had dreams, I would dream about things, scary things, I could see that I got this from here. I would panic and panic, just to panic without a reason, that when I saw that eeh…. This hospital! …” (Noma, 27 years, para 2).

“That is why most of the time we resort to staying at home so that labor may progress so that when we come in the labor ward they should find that I am towards the end. They will leave you in there, they won’t check you. After a long time they will say to you, you are going for an operation, meanwhile they left you there without being examined” (Noma, 27 years, para 2).

3.9. Manipulation

“No! What I was thinking is that I should push, I think that’s when I will get help, because as long as you are sitting there, they are also relaxing… Yes, because except you calling them, saying can I please go to the toilet, can I please get this and that, they won’t come to check you” (Johanna, 30 years, para 2).

“… I was busy pushing, and examined me and said, you should not push anymore your baby is still far. You see? I said Okay… I felt that the pain was causing me to push, so I pushed and pushed, I called her and she was not coming” (Puleng, 20 years, para 1).

4. Discussions

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Maputle, S.M.; Hiss, D. Midwives’ experiences of managing women in labour in the Limpopo Province of South Africa. Curationis 2010, 33, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ten Hoope-Bender, P.; de Bernis, L.; Campbell, J.; Downe, S.; Fauveau, V.; Fogstad, H.; Homer, C.S.; Kennedy, H.P.; Matthews, Z.; McFadden, A. Improvement of maternal and newborn health through midwifery. Lancet 2014, 384, 1226–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, R.J.; Cooper, D.; Harries, J. Narratives of distress about birth in South African public maternity settings: A qualitative study. Midwifery 2014, 30, 862–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, S.A.; George, A.S.; Chebet, J.J.; Mosha, I.H.; Mpembeni, R.N.; Winch, P.J. Experiences of and responses to disrespectful maternity care and abuse during childbirth; a qualitative study with women and men in Morogoro Region, Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. The Prevention and Elimination of Disrespect and Abuse during Facility-Based Childbirth; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 201–210. [Google Scholar]

- National Committee on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths. Saving Mothers 2014-2016: Seventh Triennial Report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in South Africa: Executive Summary; National Department of Health: Pretoria, South Africa, 2018.

- Pickles, C. Eliminating abusive ‘care’: A criminal law response to obstetric violence in South Africa. S. Afr. Crime Q. 2015, 54, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohren, M.A.; Vogel, J.P.; Hunter, E.C.; Lutsiv, O.; Makh, S.K.; Souza, J.P.; Aguiar, C.; Coneglian, F.S.; Diniz, A.L.A.; Tunçalp, Ö. The mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities globally: A mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengane, M. Mothers’ expectations of midwives’ care during labour in a public hospital in Gauteng. Curationis 2013, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltenburg, A.S.; Lambermon, F.; Hamelink, C.; Meguid, T. Maternity care and Human Rights: What do women think? BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2016, 16, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renfrew, M.J.; McFadden, A.; Bastos, M.H.; Campbell, J.; Channon, A.A.; Cheung, N.F.; Silva, D.R.A.D.; Downe, S.; Kennedy, H.P.; Malata, A. Midwifery and quality care: Findings from a new evidence-informed framework for maternal and newborn care. Lancet 2014, 384, 1129–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, H.E.; Lynam, P.F.; Carr, C.; Reis, V.; Ricca, J.; Bazant, E.S.; Bartlett, L.A. Direct observation of respectful maternity care in five countries: A cross-sectional study of health facilities in East and Southern Africa. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosthuizen, S.J.; Bergh, A.-M.; Pattinson, R.C.; Grimbeek, J. It does matter where you come from: Mothers’ experiences of childbirth in midwife obstetric units, Tshwane, South Africa. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Department of Health. Guidelines for Maternity Care in South Africa: A Manual for Clinics, Community Health Care Centres and District Hospitals; National Committee on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths: Pretoria, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Orpin, J.; Puthussery, S.; Davidson, R.; Burden, B. Women’s experiences of disrespect and abuse in maternity care facilities in Benue State, Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimoda, K.; Horiuchi, S.; Leshabari, S.; Shimpuku, Y. Midwives’ respect and disrespect of women during facility-based childbirth in urban Tanzania: A qualitative study. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brink, H.; Van der Walt, C.; Van Rensburg, G. Fundamentals of Research Methodology for Health Care Professionals; Juta and Company Ltd.: Cape Town, South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; Taylor, J.; Eley, N.; McKenna, K. Comparing focus groups and individual interviews: Findings from a randomized study. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2017, 20, 693–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, L.P.; Ramsey, K.; Abuya, T.; Bellows, B.; Ndwiga, C.; Warren, C.E.; Kujawski, S.; Moyo, W.; Kruk, M.E.; Mbaruku, G. Defining disrespect and abuse of women in childbirth: A research, policy and rights agenda. Bull. World Health Organ. 2014, 92, 915–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.; Jackson, R.; Dietsch, E.; Hailemariam, A. Barriers and facilitators to accessing skilled birth attendants in Afar region, Ethiopia. Midwifery 2015, 31, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirkuzie, A.H. Exploring inequities in skilled care at birth among migrant population in a metropolitan city Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; a qualitative study. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, C.A.; Adongo, P.B.; Aborigo, R.A.; Hodgson, A.; Engmann, C.M. ‘They treat you like you are not a human being’: Maltreatment during labour and delivery in rural northern Ghana. Midwifery 2014, 30, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruk, M.E.; Kujawski, S.; Mbaruku, G.; Ramsey, K.; Moyo, W.; Freedman, L.P. Disrespectful and abusive treatment during facility delivery in Tanzania: A facility and community survey. Health Policy Plan. 2014, 33, e26–e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asefa, A.; Bekele, D. Status of respectful and non-abusive care during facility-based childbirth in a hospital and health centers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Reprod. Health 2015, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, C. The delivery room: Is it a safe place? A hermeneutic analysis of women’s negative birth experiences. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2014, 5, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, G.; Penn-Kekana, L.; Halder, K.; Filippi, V. An investigation into mistreatment of women during labour and childbirth in maternity care facilities in Uttar Pradesh, India: A mixed methods study. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zitha, E.; Mokgatle, M.M. Women’s Views of and Responses to Maternity Services Rendered during Labor and Childbirth in Maternity Units in a Semi-Rural District in South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5035. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145035

Zitha E, Mokgatle MM. Women’s Views of and Responses to Maternity Services Rendered during Labor and Childbirth in Maternity Units in a Semi-Rural District in South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(14):5035. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145035

Chicago/Turabian StyleZitha, Elizabeth, and Mathilda M. Mokgatle. 2020. "Women’s Views of and Responses to Maternity Services Rendered during Labor and Childbirth in Maternity Units in a Semi-Rural District in South Africa" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 14: 5035. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145035

APA StyleZitha, E., & Mokgatle, M. M. (2020). Women’s Views of and Responses to Maternity Services Rendered during Labor and Childbirth in Maternity Units in a Semi-Rural District in South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(14), 5035. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145035