Increasing Competitiveness through the Implementation of Lean Management in Healthcare

Abstract

1. Introduction

“an emergent inquiry process in which applied behavioural science knowledge is integrated with existing organizational knowledge and applied to address real organizational issues. It is simultaneously concerned with bringing about change in organizations, in developing self-help competencies in organizational members and adding to scientific knowledge. Finally, it is an evolving process that is undertaken in a spirit of collaboration and co-inquiry”.[19]

2. Materials and Methods

“the design science paradigm has its roots in engineering and the sciences of the artificial. It is fundamentally a problem-solving paradigm. It seeks to create innovations that define the ideas, practices, technical capabilities, and products through which the analysis, design, implementation, and use of information systems can be effectively and efficiently accomplished. Acquiring such knowledge involves two complementary but distinct paradigms, natural (or behavioral) science and design science”.

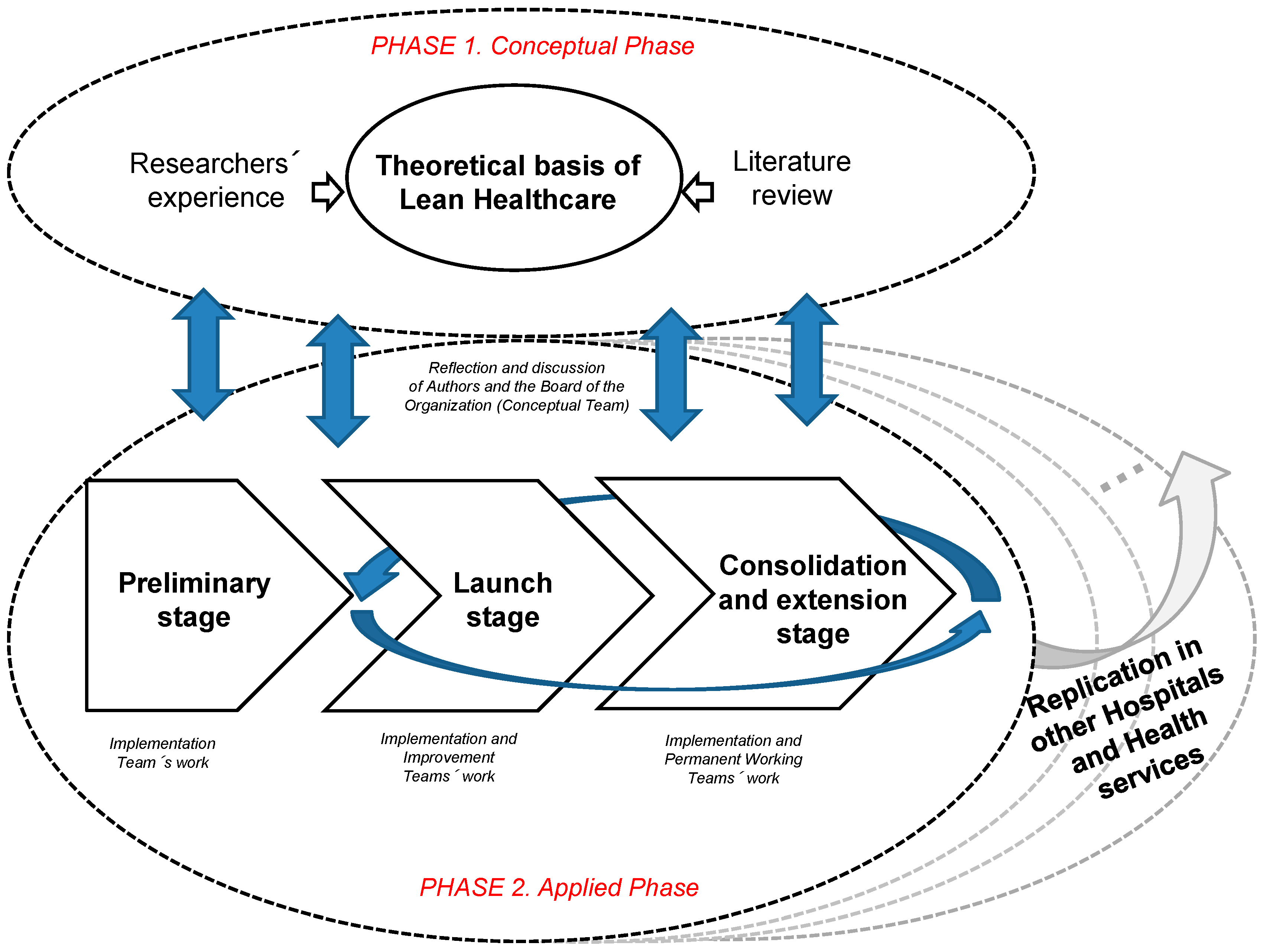

2.1. Phase 1 (Conceptual Phase): Structuring lean Principles in Hhealthcare

“The three critical changes healthcare organizations have to undertake are a leadership commitment to zero major quality failures, the full embodiment and implementation of safety culture and the full deployment of robust process improvement”.[51]

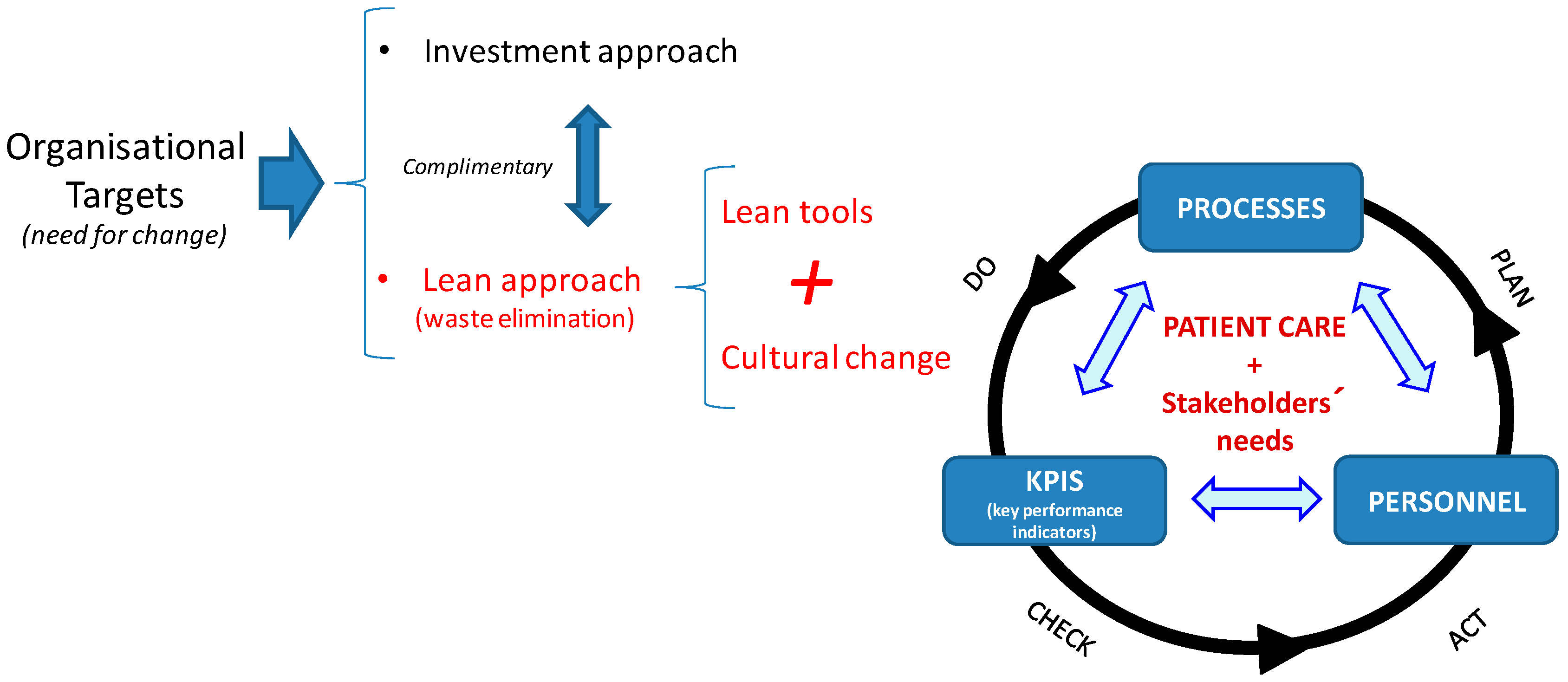

- Processes: An organisation is the sum of interrelated processes aimed at offering a quality, effective and efficient service. The organisation can take direct action on internal processes to improve its results, since these internal processes consume resources and can generate waste or add value for the patient. However, it cannot take direct action on patient needs or the results obtained. In healthcare, many processes require patient involvement.Therefore, these processes are key elements to take into account when offering greater customer satisfaction. In order to maximise value and eliminate waste, processes must be evaluated by accurately specifying the value desired by the user, identifying every step in the process and eliminating non-value-added activities, and making value flow from beginning to end based on the pull of the patient [60]; in the jargon of lean management and kaizen, this involves “Go to Gemba”. In this context, the adoption of some Lean tools is useful, particularly, the value stream maps (VSM). Logically, the complexity of the processes being analysed will require more or less diversity in the Lean tools or practices;

- Key performance indicators (KPIS): “What doesn’t get measured doesn’t get managed”. All processes involving change must come with clearly defined goals and objectives, for which there must be well defined indicators. These indicators act as a sort of “mediator” between the system goals and the required actions to achieve these, and thereby become more competitive. These indicators are necessary to measure results and identify deviations from the optimum, as well as trends in values.Ultimately, they supply data concerning the system variability and support decisions regarding the taking of preventive or corrective actions. Such indicators will be helpful in determining the current status of the system in terms of effectiveness, efficiency, variability, capacity and quality provided as well as in establishing preventive or corrective actions in the event of detecting deviations from the defined objectives. According to Kissoon [61], it is insufficient to innovate and introduce new processes in healthcare; it is necessary to constantly evaluate the results of the interventions and make the appropriate changes as necessary. Logically, the specific indicators and objectives for the lean management transformation project should be coherent and aligned with the organisation’s overall objectives;

- Personnel involvement: The activities involved in each process are best understood by the personnel, since these processes form part of their daily work routine. Therefore, if they are equipped with the correct tools, they will be able to identify areas for improvement, implement actions and take responsibility for its follow-up and control. For this reason, it is vital to involve personnel from the beginning thereby serving as a motivating factor in their commitment to the process of change. In order to do so, the researchers defined the work organisation for the project based on teams (see next section).

2.2. Phase 2 (Applied phase): Implementing the Methodology

- The availability of KPIS for measuring improvement, one of the pillars of our model;

- A preestablished calendar for meetings with dates, start times and lengths. This calendar is usually proposed and justified by the implementation team (not only for their own meetings but for those of the improvement teams), depending on availability and the priority and pace they assign to the project;

- The training program. This program includes both traditional training techniques associated with problem solving, lean tools and an awareness of improvement and teamwork. Some authors recommend complementing this basic training with “learning-by-doing”;

- Communication. This aspect implies the way that actions agreed upon at meetings are documented and communicated, including tasks, responsibilities and deadlines. It can take many forms such as information boards, magazines, intranet, public presentations, etc. For example, the conclusions reached at all the meetings were typically recorded in the minutes, which were sent electronically to the members of the various teams and used for discussion and reflection at the next meeting. Likewise, the main progress, improvements and adopted changes were communicated to the affected areas, departments or centres.

- Resources. These resources were necessary for the proposed improvements to become a reality. A lack of resources available for developing improvements can discourage team members and reduce their commitment to participation programs. In the service sector, particularly in healthcare, the adaptation and suitability of the information system for decision making takes on particular importance.

- Recognition/Reward. This aspect has an important impact on personnel motivation, and consequently on their commitment to lean management projects. Literature differentiates between “reward” (essentially economic), or a “payment in kind”, and “recognition” (essentially social).

3. Testing the Methodology

3.1. Preliminary Stage

- A patient with a suspected case of SAHS arrives at the sleep unit following a referral from either a general practitioner (GP) or a specialist;

- At the first consultation, notes are taken of the patient’s parameters and symptoms, and the patient completes a test which is designed to establish the extent of suspected SAHS;

- Following this first consultation, the patient undergoes a diagnostic test in order to determine the frequency of apneas and the seriousness of the illness;

- Once completed, doctors draft a report with the patient’s diagnosis and then they contact the patient to review the test results;

- At this point, the patient may be discharged if the test shows that there is no illness or, alternatively, may start home treatment;

- Treatment requires the patient to sleep while connected to the CPAP, which is supplied by a home care services company specializing in oxygen therapy (hereafter, “external care provider”);

- Periodically, the external care provider supplies machine data to the sleep unit, allowing doctors to make the appropriate adjustments to the machine;

- In the following months, a control test is run on the patient to check his/her development with the treatment. If development is positive, the patient is discharged, otherwise regular checks will be carried out at the hospital. Once the treatment has started, the external care provider company also makes follow-up visits to the patient’s home on a quarterly basis.

- Those who refer patients to the sleep unit: GPs or specialists;

- Sleep unit personnel: head of the pneumology department, sleep unit manager, doctors, nurses and technicians;

- External care provider: nurses who provide home care during treatment.

3.2. Launching Stage

3.3. Consolidation and Extension Stage

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Future Avenues

5.2. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thuemmler, C.; Bai, C. Health 4.0: How Virtualization and Big Data are Revolutionizing Healthcare; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2F978-3-319-47617-9 (accessed on 9 July 2020).

- García-Arca, J.; Prado-Prado, J.C.; Fernandez-González, A.J. Promoting structured participation for competitiveness in services companies. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2018, 11, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawal, A.; Rotter, T.; Kinsman, L.; Sari, N.; Harrison, E.; Jeffery, C.; Kutz, M.; Khan, M.F.; Flynn, R. Lean management in health care: Definition, concepts, methodology and effects reported (systematic review protocol). Syst. Rev. 2014, 3, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Röck, R.L.; Dammand, J.; Hørlyck, M.; Jacobsen, T.L.; Lueg, R. Lean management in hospitals: Evidence from Denmark. Adm. Public Manag. Rev. 2014, 14, 19–35. Available online: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=170204 (accessed on 9 July 2020).

- Daultani, Y.; Chaudhuri, A.; Kumar, S. A Decade of Lean in Healthcare: Current State and Future Directions. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2015, 16, 1082–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggat, S.; Bartram, T.; Stanton, P.; Bamber, G.J.; Sohal, A.S. Have process redesign methods, such as Lean, been successful in changing care delivery in hospitals? A systematic review. Public Money Manag. 2015, 35, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida, J.P.L.; Galina, S.V.; Grande, M.M.; Brum, D.G. Lean thinking: Planning and implementation in the public sector. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma 2017, 8, 390–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleu, F.G.; Van Aken, E.; Cross, J.; Glover, W. Continuous improvement project within Kaizen: Critical success factors in hospitals. TQM J. 2018, 30, 335–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, T.; Plishka, C.; Lawal, A.; Harrison, L.; Sari, N.; Goodridge, N.; Flynn, R.; Chan, J.; Fiander, M.; Poksinska, B.; et al. What Is Lean Management in Health Care? Development of an Operational Definition for a Cochrane Systematic Review. Eval. Health Prof. 2018, 42, 366–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isfahani, H.M.; Tourani, S.; Seyedin, H. Lean management approach in hospitals: A systematic review. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma 2019, 10, 161–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkhi, S.S. Lean management practices in healthcare sector: A literature review. Benchmarking Int. J. 2019, 26, 1275–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V.; Samuel, C.; Sharma, S.K. Lean, agile and leagile healthcare management–A case of chronic care. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2019, 12, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Barraza, M.F.; Miguel-Dávila, J.A. Kaizen–Kata, a problem-solving approach to public service health care in Mexico. A multiple-case study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marksberry, P.; Church, J.; Schmidt, M. The employee suggestion system: A new approach using latent semantic analysis. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. 2014, 24, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin-Garcia, J.A.; Bonavia, T. Relationship between employee involvement and lean manufacturing and its effect on performance in a rigid continuous process industry. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 53, 3260–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Arca, J.; Prado-Prado, J.C.; Fernández-González, A.J. Integrating KPIs for improving efficiency in road transport. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2018, 48, 931–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drotz, E.; Poksinska, B. Lean in healthcare from employees’ perspectives. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2014, 28, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walley, P. Designing the accident and emergency system: Lessons from manufacturing. Emerg. Med. J. 2003, 20, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shani, A.B.R.; Coghlan, D. Action research in business and management: A reflective review. Action Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, R. Action research: A new paradigm for research in production and operations management. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 1995, 15, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevner, A.R.; Chatterjee, S. Design Science Research in Information Systems. In Design Research in Information Systems. Integrated Series in Information Systems; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; Volume 22, pp. 9–22. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4419-5653-8_2 (accessed on 9 July 2020).

- Coughlan, P.; Coghlan, D. Action research for operations management. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2002, 22, 220–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prybutok, V.; Ramasesh, R. An action-research based instrument for monitoring continuous quality improvement. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2005, 166, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, R.; Bolumole, Y.; Näslund, D. The “white space” of logistics research: A look at the role of methods usage. J. Bus. Logist. 2005, 26, 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raelin, J.; Coghlan, D. Developing managers as learners and researchers: Using action learning and action research. J. Manag. Educ. 2006, 30, 670–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Näslund, D.; Kale, R.; Paulraj, A. Action research in supply chain management-a framework for relevant and rigorous research. J. Bus. Logist. 2010, 31, 331–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlan, P.; Draaijer, D.; Godsell, J.; Boer, H. Operations and supply chain management: The role of academics and practitioners in the development of research and practice. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2016, 36, 1673–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.F. Research that makes a difference. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2014, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Arca, J.; Prado-Prado, J.C.; Garrido, A.T.G.-P. On-shelf availability and logistics rationalization. A participative methodology for supply chain improvement. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, S.; O’Brien, C. An action research methodology for manufacturing technology selection: A supply chain perspective. Prod. Plan. Control. 2015, 26, 467–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, L.; Blanco, B.; Simón, R.M. Business process management in healthcare. Sant camil hospital case study. In Proceedings of the 4th Production and Operations Management World Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1–5 July 2012; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Hellström, A.; Lifvergren, S.; Gustavsson, S. Transforming a healthcare organization so that it is capable of continual improvement–the integration of improvement knowledge. In Proceedings of the 18th EurOMA Conference, Cambridge, UK, 3–6 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ohno, T. Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production; Productivity Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Womack, J.P.; Jones, D.T.; Roos, D. The Machine that Changed the World: The Story of Lean Production–How Japan’s Secret Weapon in the Global Auto Wars Will Revolutionize Western Industry; Rawson Associates: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, R.; Ward, P.T. Defining and developing measures of lean production. J. Oper. Manag. 2007, 25, 785–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, R.; Canacari, E.G. A practical guide to applying lean tools and management principles to health care improvement projects. AORN J. 2012, 95, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Womack, J.P.; Jones, D.T. Lean Thinking: Banish Waste and Create Wealth in Your Corporation, Revised and Updated; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kollberg, B.; Dahlgaard, J.J.; Brehmer, P.-O. Measuring lean initiatives in health care services: Issues and findings. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 2006, 56, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, L.B. Trends and approaches in lean healthcare. Leadersh. Health Serv. 2009, 22, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.B.M.; Filho, M.G. Lean healthcare: Review, classification and analysis of literature. Prod. Plan. Control. 2016, 27, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liker, J.K. The Toyota Way: 14 Management Principle from the World’s Greates Manufacturer; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Womack, J.P. Going Lean in Healthcare; Institute for Healthcare Improvement: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Melão, N.; Pidd, M. A conceptual framework for understanding business processes and business process modelling. Inf. Syst. J. 2000, 10, 105–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Savén, R.S. Business process modelling: Review and framework. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2004, 90, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgaard, J.J.; Pettersen, J.; Dahlgaard-Park, S.M.; Langstrand, J. Quality and lean health care: A system for assessing and improving the health of healthcare organisations. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2011, 22, 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, N.; Radnor, Z. Trajectory of lean implementation: The case of English hospitals. In Proceedings of the 18th EurOMA Conference, Cambridge, UK, 3–6 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Radnor, Z. Transferring Lean into government. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2010, 21, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillingham, D. Can lean save lives? Leadersh. Health Serv. 2007, 20, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, P.; Lethbridge, S. New development: Creating a lean university. Public Money Manag. 2010, 28, 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Radnor, Z.; Burgess, N.; Sohal, A.S.; O’Neill, P. Readiness for lean in healthcare: Views from the executive. In Proceedings of the 18th EUROMA Conference, Cambridge, UK, 3–6 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, H. A teaching moment. Goodbye best practice, hello lean. Hosp. Health Netw. 2012, 86, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Cottington, S.; Forst, S. Lean Healthcare: Get Your Facility into Shape; HCPro: Danvers, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Graban, M. Lean Hospitals: Improving Quality, Patient Safety, and Employee Satisfaction; Productivity Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gowen, C.R., III; McFadden, K.L.; Settaluri, S. Contrasting continuous quality improvement, Six Sigma, and lean management for enhanced outcomes in US hospitals. Am. J. Bus. 2012, 27, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marley, K.A.; Collier, D.A.; Goldstein, S.M. The role of clinical and process quality in achieving patient satisfaction in hospitals. Decis. Sci. 2004, 35, 349–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, R.; Balla, M.; Sohal, A. Factors critical to the success of a six-sigma quality program in an Australian hospital. Total. Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2008, 19, 887–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, D.H.; Holsenback, J.E. The use of six sigma in health care operations: Application and opportunity. Acad. Health Care Manag. J. 2006, 2, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, G.S.; Patterson, S.H.; Ching, J.M.; Blackmore, C.C. Why Lean doesn’t work for everyone. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2014, 23, 970–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Rossum, L.; Aij, K.H.; Simons, F.E.; Van Der Eng, N.; Have, W.D.T. Lean healthcare from a change management perspective: The role of leadership and workforce flexibility in an operating theatre. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2016, 30, 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, H.; Bateman, N.; Radnor, Z. Beyond the ostensible: An exploration of barriers to lean implementation and sustainability in healthcare. Prod. Plan. Control. 2020, 31, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissoon, N. The Toyota way...or not? New lessons for healthcare. Physician Exec. J. 2010, 36, 40–42. [Google Scholar]

- García-Arca, J.; Prado-Prado, J.C. Systematic personnel participation for logistics improvement: A case study. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. 2010, 21, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin-Garcia, J.A.; Pardo-Del-Val, M.; Martín, T.B. Longitudinal study of the results of continuous improvement in an industrial company. Team Perform. Manag. Int. J. 2008, 14, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherrer-Rathje, M.; Boyle, T.A.; Deflorin, P. Lean, take two! Reflections from the second attempt at lean implementation. Bus. Horiz. 2009, 52, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaca, C.; Santos, J.; Errasti, A.; Viles, E. Lean thinking with improvement teams in retail distribution: A case study. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2012, 23, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaca, C.; Viles, E.; Mateo, R.; Santos, J. Components of sustainable improvement systems: Theory and practice. TQM J. 2012, 24, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado-Prado, J.C.; García-Arca, J.; Fernández-González, A.J. People as the key factor in competitiveness: A framework for success in supply chain management. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2020, 31, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurburg, D.; Viles, E.; Tanco, M.; Mateo, R.; Lleó, Á. Understanding the main organisational antecedents of employee participation in continuous improvement. TQM J. 2019, 31, 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, D.M.; Scavarda, L.F.; Fiorencio, L.; Martins, R.A. Evolution of the performance measurement system in the Logistics Department of a broadcasting company: An action research. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 160, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touboulic, A.; Walker, H. A relational, transformative and engaged approach to sustainable supply chain management: The potential of action research. Hum. Relat. 2016, 69, 301–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Capasso, V. Improving patient flow through a better discharge process. J. Health Manag. 2012, 57, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noon, C.E.; Hankins, C.T.; Côté, M.J. Understanding the impact of variation in the delivery of healthcare services. J. Health Manag. 2003, 48, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvester, K.; Lendon, R.; Bevan, H.; Steyn, R.; Walley, P. Reducing waiting times in the NHS: Is lack of capacity the problem? Clin. Manag. 2004, 12, 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, C.P. Why variation reduction is not everything: A new paradigm for service operations. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1996, 7, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towne, J. Lean transformations. Planning a ‘lean’ healthcare makeover. Health Facil. Manag. 2010, 23, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- De Treville, S.; Antonakis, J.; Edelson, N.M. Can standard operating procedures be motivating? Reconciling process variability issues and behavioural outcomes1. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2005, 16, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castle, A.; Harvey, R. Lean information management: The use of observational data in health care. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 2009, 58, 280–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, K.; Hinton, J.; Kraebber, K. The gradual leaning of health systems. Ind. Eng. IE 2010, 42, 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Goodyer, J.; Murti, Y.; Grigg, N.P.; Shekar, A. Lean: Insights into SMEs ability to sustain improvement. In Proceedings of the 18th EurOMA Conference, Cambridge, UK, 3–6 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Type of Waste | Comments |

|---|---|

| Long patient waiting lists between processes in the unit | When starting treatment in the sleep unit, the patient must queue for two processes: the diagnostic test and results review. The patient waiting times for each of these processes was measured from the beginning of the project. Corresponding data from the previous year was collected and analysed. In the case of the diagnostic test, the average waiting time for the 211 patients on the waiting list was 67 days, and in the case of the results review, the average waiting time for the 673 patients of the waiting list was 49 days. In both cases there was a high variability in waiting time. |

| Repetition of diagnostic tests | Some of the monthly diagnostic tests showed an error when analysed on the computer. Those responsible were asked to analyse the results of the diagnostic tests which showed a fault, so as to find its source. At the same time, they registered the diagnostic tests which had been carried out on each of the Unit’s six machines. From this they were able to establish that the most common causes for the fault were: human error due to the patient’s incorrect positioning of the apparatus, a fault in the apparatus itself and a computer fault in downloading the test. During a sample over seven months, there were 482 diagnostic tests, 36 (7.5%) of which were repeated. |

| Repetitive medical consultations in the unit due to the fact of maladjustment of the CPAP | The mask connecting the patient to the CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) must be adapted to each patient. Consequently, there were different types of mask. An inadequately fitted mask can cause discomfort while the patient is sleeping, dry mouth, disconnection from the CPAP, or breakage. Before beginning home treatment with the CPAP, the patient is fitted with the most suitable type of mask. However, the patient usually experiences discomfort with the mask after continuous use of the CPAP. Therefore, the majority of return visits to the sleep unit by patients already in treatment are due to maladjustment of the mask. These visits interrupt the scheduled appointments for patients still in the diagnostic stage of the illness. |

| Type of Waste | Comments |

|---|---|

| Delays in drafting diagnostic reports | Before a patient can begin treatment, sleep unit doctors must firstly draft a report on the results of the diagnostic test. In the Unit there were files full of diagnostic test results waiting to be drafted in reports. Managers were unable to estimate how many reports were pending, but the files contained diagnostic test results that were more than one year old. The sleep unit doctors drafted reports whenever they managed to have some free time. |

| Patients who do not follow the treatment | Unit managers were aware that some patients who had started home treatment were not using the CPAP for the time required for an effective treatment. However, they were unable to estimate how many patients underused the CPAP or the number of patients receiving treatment. The economic cost of each CPAP amounts to €1.35 per day and 15 patients were identified as not having used the machine for more than 10 years. Halfway through the project, 4137 patients in home treatment had been recorded, 15.52% of those used the CPAP for less time than was required for an effective treatment. |

| Sleep unit specialists dedicating time to activities outside the unit | Sleep unit patients achieve added value through the effective treatment of SAHS. Apart from spending time on activities that add value for patients, doctors and nurses from the sleep unit carry out other activities within the pneumology department such as visiting admitted patients, receiving visits from supervisors, and helping with other activities outside the unit. These activities do not form part of their schedule, and when they arise, doctors and nurses must improvise in order to maintain a minimum service in the sleep unit. |

| Paper support information system | Initially, all information handled within the unit was on paper, such as the appointments diary, reports on test results, and forms to be filled out by both doctor and patient during the consultation. A large amount of paper-based information was collected from different points along the patient flow which led to the duplication of some data. This complicated data analysis and patient traceability for the unit management. |

| Difference in criteria for diagnosis and discharge of patients | After pooling the criteria for patient referral to the unit and the criteria followed by unit doctors for patient discharge, there appears to be no uniformity of criteria for decision making. |

| Impossible to quickly and easily understand different aspects of unit management | Essential aspects of unit management such as knowing the current workload, the traceability of each patient, or the productivity of the unit, were difficult if not impossible for the unit specialists to understand. This was due to a lack of defined indicators and a lack of information to create them. |

| Type of Improvement | Comments |

|---|---|

| Categorisation and prioritisation of patients according to seriousness | Three different patient categories were defined depending on the seriousness of the illness, the risk of accident due to the symptoms of the illness and the patient’s profession (the risk of accident is higher if a professional driver suffers from drowsiness, rather than an administrator). The categories of urgent, preferential and normal were established. The appropriate category is assigned to the patient by sleep unit professionals in the first consultation. Any patient diagnosed as urgent is always given priority in the flow. This action is similar to the triage method used in emergency departments. This method efficiently rations patient treatment when there are insufficient resources for all to be treated immediately. The sleep unit has a large number of patients on waiting lists. Since it is not possible to attend to all patients at once, priorities were established for administering medical care. |

| Drafting technical instructions | Technical instructions were drawn up for all activities where the probability of human error occurring was greater. The instructions explained the optimal way to carry out these activities. In the case of the diagnostic test apparatus, step-by-step instructions were drawn up for the positioning of each part of apparatus. Each step contained a small photo with an explanatory text. These technical instructions were posted on the wall in the sleep unit and placed in the bags that contained the diagnostic test apparatus. |

| Action procedure for patients who do not adhere to treatment | An action procedure was drawn up in conjunction with the external care provider company to identify patients that voluntarily underused the CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure). Under this procedure, the external care provider company would report a monthly list of non-adherent patients (including their reasons for not using the CPAP) and the sleep unit would evaluate each particular case. By way of example, for a patient who used the CPAP, but not sufficiently, efforts would be made to re-educate the patient in its use. In the case of a patient who did not use the CPAP at all or refused to use it despite having been re-educated in its use, sleep unit doctors would have the necessary authority to recall the CPAP. |

| Categorisation and prioritisation of doctors’ activities | The daily activities carried out by unit doctors were recorded over a three-week period. These activities were classified into three categories: key activities that impact patients directly, such as consultations; general activities that impact patients indirectly, such as training sessions for unit staff; and other activities that do not add value for the patient, such as meeting unit visitors. Target percentages for the time dedicated daily to each type of activity were established: 70% for key activities, 20% for general activities, and 10% for the rest. In addition, a proposed weekly schedule for doctors’ activities was drawn up. |

| Computerisation of data capture, storage and analysis | During the case study, an “Access” computer application was developed to capture, store and analyse all data handled within the sleep unit. This includes doctor and patient forms, medical reports, test results and so on. Data capture, analysis, treatment, and storage would be centralised in a single application and database. The patient appointment process was also systemised. Each patient was automatically allocated the maximum admissible time within which he/she should be seen (by appointment), in line with the patient’s previously assigned category of urgent, preferential or normal. The patients on the waiting list were arranged from most to least urgent according to this maximum admissible time for receiving an appointment. Furthermore, if the patient is not seen within this maximum admissible time, a notice is sent to the person in charge of managing the appointment process. |

| Development of internal procedures and protocols | Internal procedures and protocols were drafted in order to standardise processes that were carried out by different doctors. This sought to homogenise diagnosis and treatment criteria for patients, reduce the probability of producing human error, and facilitate the task of estimating productivity, quality and efficiency indices. |

| Defining indicators that are linked to objectives | Indicators were defined for the appropriate management of each value adding activity. These indicators were established to measure the following: unit productivity, such as the number of consultations per week and number of reports drafted per week; quality, in terms of waiting time to access the system, waiting time between processes, total accrued patient waiting time, rate of test repetition and number of patients not adhering to treatment; system load, as in the number of patients in the system, number under treatment compared to the number of diagnostic tests and number of patients suffering from or with symptoms of the illness. Depending on the situation, either a target value or an admissible value was established for each indicator. |

| Type of KPI (Key Performance Indicators) | Description | Initial Average Value | Current Average Value | Variation (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Productivity | Number of first consultations per week | 20 | 20 | - | ||

| Number of diagnostic tests per week | 14 | 20 | 42.8% | |||

| Number of reports drafted per week | 26 | 28 | 7.7% | |||

| Quality | Waiting time for the patient (days) | From first consultation to diagnostic test | Urgent | 67 | 19 | 71.6% |

| Preferential | 62 | 7.5% | ||||

| Normal | 148 | −121% | ||||

| From diagnostic test to results review | Urgent | 49 | 9 | 81.6% | ||

| Preferential | 15 | 69.3% | ||||

| Urgent | 30 | 38.7% | ||||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prado-Prado, J.C.; García-Arca, J.; Fernández-González, A.J.; Mosteiro-Añón, M. Increasing Competitiveness through the Implementation of Lean Management in Healthcare. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4981. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144981

Prado-Prado JC, García-Arca J, Fernández-González AJ, Mosteiro-Añón M. Increasing Competitiveness through the Implementation of Lean Management in Healthcare. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(14):4981. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144981

Chicago/Turabian StylePrado-Prado, J. Carlos, Jesús García-Arca, Arturo J. Fernández-González, and Mar Mosteiro-Añón. 2020. "Increasing Competitiveness through the Implementation of Lean Management in Healthcare" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 14: 4981. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144981

APA StylePrado-Prado, J. C., García-Arca, J., Fernández-González, A. J., & Mosteiro-Añón, M. (2020). Increasing Competitiveness through the Implementation of Lean Management in Healthcare. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(14), 4981. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144981