How Can Work Addiction Buffer the Influence of Work Intensification on Workplace Well-Being? The Mediating Role of Job Crafting

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Work Intensification and Well-Being

1.2. Work Intensification and Job Crafting

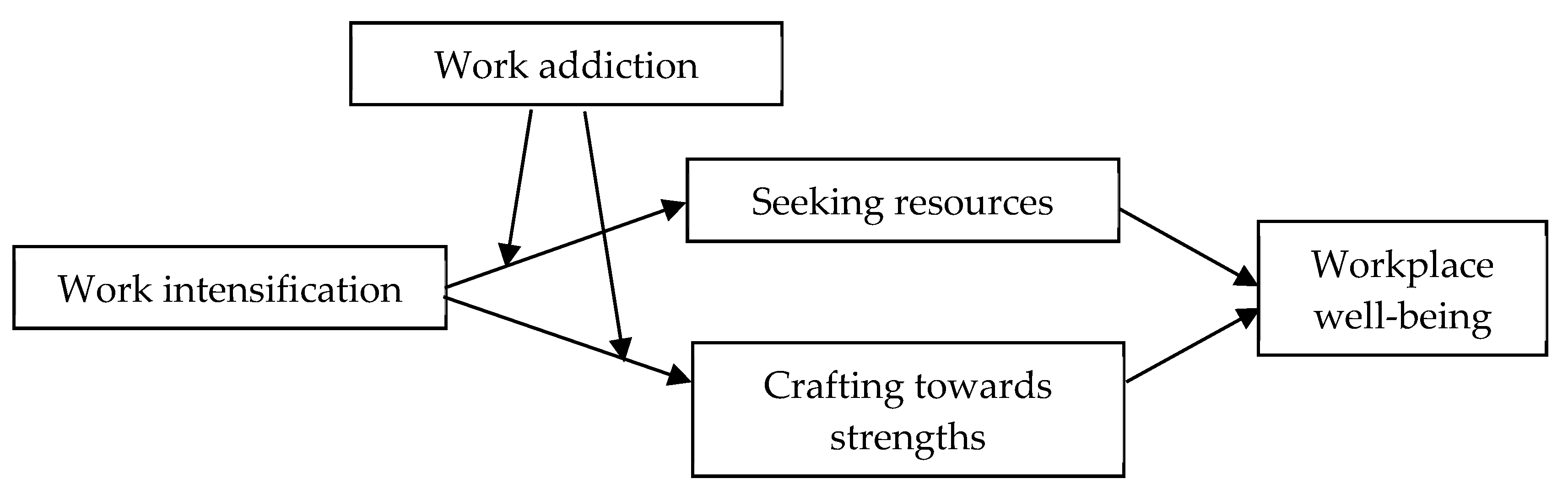

1.3. Moderated Mediation Model

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Work Intensification

2.2.2. Work Addiction

2.2.3. Workplace Well-Being

2.2.4. Seeking Resources

2.2.5. Crafting Towards Strengths

2.2.6. Control Variables

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.2. Descriptive Statistics

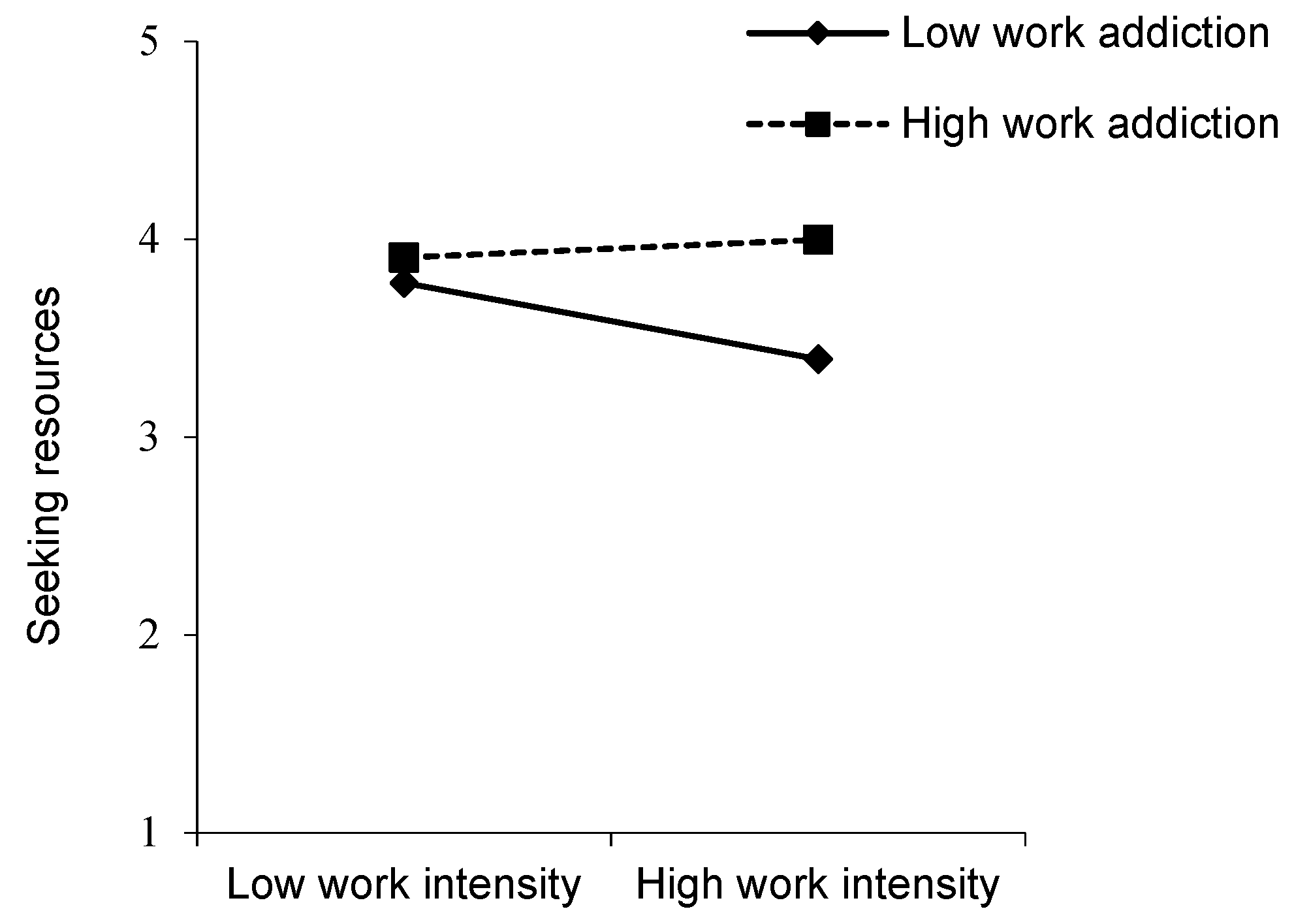

3.3. Hypothesis Tests

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kubicek, B.; Paškvan, M.; Korunka, C. Development and validation of an instrument for assessing job demands arising from accelerated change: The intensification of job demands scale (IDS). Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 24, 898–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paškvan, M.; Kubicek, B.; Prem, R.; Korunka, C. Cognitive appraisal of work intensification. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2016, 23, 124–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B. The Job Demands–Resources model: Challenges for future research. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2011, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubicek, B.; Korunka, C.; Ulferts, H. Acceleration in the care of older adults: New demands as predictors of employee burnout and engagement. J. Adv. Nurs. 2013, 69, 1525–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korunka, C.; Kubicek, B.; Paškvan, M.; Ulferts, H. Changes in work intensification and intensified learning: Challenge or hindrance demands? J. Manag. Psychol. 2015, 30, 786–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepine, J.A.; Podsakoff, N.P.; Lepine, M.A. A meta-analytic test of the challenge stressor--hindrance stressor framework: An explanation for inconsistent relationships among stressors and performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; LePine, J.A.; LePine, M.A. Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 438–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M. Responses to work intensification: Does generation matter? Int.l J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 3578–3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.A.; Michel, J.S.; Zhdanova, L.; Pui, S.Y.; Baltes, B.B. All Work and No Play? A Meta-Analytic Examination of the Correlates and Outcomes of Workaholism. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1836–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Peeters, M.C.W.; Schaufeli, W.B. Different types of employee well-being across time and their relationships with job crafting. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Bakker, A.B.; Bjorvatn, B.; Moen, B.E.; Mageroy, N.; Shimazu, A.; Hetland, J.; Pallesen, S. Working Conditions and Individual Differences Are Weakly Associated with Workaholism: A 2-3-Year Prospective Study of Shift-Working Nurses. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.B. Heavy work investment, personality and organizational climate. J. Manag. Psychol. 2016, 31, 1057–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snir, R.; Harpaz, I. Beyond workaholism: Towards a general model of heavy work investment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2012, 22, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimazu, A.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W. How does workaholism affect worker health and performance? The mediating role of coping. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2010, 17, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeijen, M.E.L.; Peeters, M.C.W.; Hakanen, J.J. Workaholism versus work engagement and job crafting: What is the role of self-management strategies? Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2018, 28, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. The impact of job crafting on job demands, job resources, and well-being. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrou, P.; Demerouti, E.; Peeters, M.C.W.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Hetland, J. Crafting a job on a daily basis: Contextual correlates and the link to work engagement. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 1120–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W.; van Rhenen, W. Workaholism, Burnout, and Work Engagement: Three of a Kind or Three Different Kinds of Employee Well-being? Appl. Psychol. 2008, 57, 173–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest, J.; Mageau, G.A.; Crevier-Braud, L.; Bergeron, É.; Dubreuil, P.; Lavigne, G.L. Harmonious passion as an explanation of the relation between signature strengths’ use and well-being at work: Test of an intervention program. Hum. Relat. 2012, 65, 1233–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, E.M.; Mostert, K. Perceived organisational support for strengths use: The factorial validity and reliability of a new scale in the banking industry. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2013, 39, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, C.; Mostert, K. A structural model of job resources, organisational and individual strengths use and work engagement. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2014, 40, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooij, D.T.A.M.; van Woerkom, M.; Wilkenloh, J.; Dorenbosch, L.; Denissen, J.J.A. Job crafting towards strengths and interests: The effects of a job crafting intervention on person–job fit and the role of age. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Woerkom, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Nishii, L.H. Accumulative job demands and support for strength use: Fine-tuning the job demands-resources model using conservation of resources theory. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, J.T.; Robbins, A.S. Workaholism: Definition, measurement, and preliminary results. J. Pers. Assess. 1992, 58, 160–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruch, Y. The positive wellbeing aspects of workaholism in cross cultural perspective. Career Dev. Int. 2011, 16, 572–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Sorensen, K.L.; Feldman, D.C. Dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of workaholism: A conceptual integration and extension. J. Organ. Behav. 2007, 28, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Sanz-Vergel, A.I. Weekly work engagement and flourishing: The role of hindrance and challenge job demands. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 83, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadić, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Oerlemans, W.G.M. Challenge versus hindrance job demands and well-being: A diary study on the moderating role of job resources. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 88, 702–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.R.; Beehr, T.A.; Love, K. Extending the challenge-hindrance model of occupational stress: The role of appraisal. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 79, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxall, P.; Macky, K. High-involvement work processes, work intensification and employee well-being. Work Employ. Soc. 2014, 28, 963–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olafsen, A.H.; Frølund, C.W. Challenge accepted! Distinguishing between challenge- and hindrance demands. J. Manag. Psychol. 2018, 33, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, A.; Vansteenkiste, M.; De Witte, H.; Lens, W. Explaining the relationships between job characteristics, burnout, and engagement: The role of basic psychological need satisfaction. Work Stress 2008, 22, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Collins, C.G. Taking Stock: Integrating and Differentiating Multiple Proactive Behaviors. J. Manag. 2008, 36, 633–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, C.W.; Katz, I.M.; Lavigne, K.N.; Zacher, H. Job crafting: A meta-analysis of relationships with individual differences, job characteristics, and work outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 102, 112–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, E.R.; LePine, J.A.; Rich, B.L. Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg, E.; Wong, S.I. Crafting one’s job to take charge of role overload: When proactivity requires adaptivity across levels. Leadersh. Q. 2016, 27, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, B.J.; Auton, J.C. The merits of measuring challenge and hindrance appraisals. Anxiety Stress Coping 2015, 28, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohly, S.; Fritz, C. Work characteristics, challenge appraisal, creativity, and proactive behavior: A multi-level study. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 543–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilboa, S.; Shirom, A.; Fried, Y.; Cooper, C.L. A Meta-Analysis of Work Demand Stressors and Job Performance: Examining Main and Moderating Effects; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Griffiths, M.D.; Hetland, J.; Pallesen, S. Development of a work addiction scale. Scand. J. Psychol. 2012, 53, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeber, J.; Rennert, D. Perfectionism in school teachers: Relations with stress appraisals, coping styles, and burnout. Anxiety Stress Coping 2008, 21, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haybatollahi, M.; Gyekye, S.A. The moderating effects of locus of control and job level on the relationship between workload and coping behaviour among Finnish nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2014, 22, 811–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Development and validation of the job crafting scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Woerkom, M.; Oerlemans, W.; Bakker, A.B. Strengths use and work engagement: A weekly diary study. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2015, 25, 384–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machteld, V.D.H.; Demerouti, E.; Peeters, M.C.W. The job crafting intervention: Effects on job resources, self-efficacy, and affective well-being. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 88, 511–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrou, P.; Demerouti, E.; Xanthopoulou, D. Regular versus cutback-related change: The role of employee job crafting in organizational change contexts of different nature. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2017, 24, 62–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Rhenen, A.B.B.V. How changes in job demands and resources predict burnout, work engagement, and sickness absenteeism. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 893–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, M.C.; van Woerkom, M. Effects of a Strengths Intervention on General and Work-Related Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Positive Affect. J. Happiness Stud. 2016, 18, 671–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzer, C.; Ruch, W. The Role of Character Strengths for Task Performance, Job Dedication, Interpersonal Facilitation, and Organizational Support. Hum. Perform. 2014, 27, 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Parker, S.K. Reorienting job crafting research: A hierarchical structure of job crafting concepts and integrative review. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 126–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenglass, E.R.; Fiksenbaum, L. Proactive Coping, Positive Affect, and Well-Being. Eur. Psychol. 2009, 14, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Yen, C.-H.; Tsai, F.C. Job crafting and job engagement: The mediating role of person-job fit. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 37, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Derks, D.; Bakker, A.B. Job crafting and its relationships with person–job fit and meaningfulness: A three-wave study. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016, 92, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Yang, T.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Deng, J. Do Challenge Stress and Hindrance Stress Affect Quality of Health Care? Empirical Evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. Methodology 1980, 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.; Zhu, W.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, C. Employee well-being in organizations: Theoretical model, scale development, and cross-cultural validation. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 621–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Xu, T. Psychological contract breach, high-performance work system and engagement: The mediated effect of person-organization fit. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 29, 1257–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions; Sage: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, S. Workaholism: A Review. J. Addict. Res. Ther. 2012, (Suppl. 6), 244–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Schaufeli, W.; Taris, T.; Hessen, D.; Hakanen, J.; Salanova, M.; Shimazu, A. East is East and West is West and never the twain shall meet: Work engagement and workaholism across Eastern and Western cultures. J. Behav. Soc. Sci. 2014, 1, 6–24. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J.R.; Lambert, L.S. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Oerlemans, W.; Sonnentag, S. Workaholism and daily recovery: A day reconstruction study of leisure activities. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S.; Uhrich, B.; Wuensch, K.L.; Swords, B. The Workaholism Analysis Questionnaire: Emphasizing Work-Life Imbalance and Addiction in the Measurement of Workaholism. J. Behav. Appl. Manag. 2013, 14, 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Spagnoli, P.; Balducci, C.; Scafuri Kovalchuk, L.; Maiorano, F.; Buono, C. Are Engaged Workaholics Protected against Job-Related Negative Affect and Anxiety before Sleep? A Study of the Moderating Role of Gender. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| χ2 | df | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-factor model | 3522.51 | 230 | 0.201 | 0.39 | 0.33 | 0.195 |

| 2-factor model | 3000.16 | 229 | 0.184 | 0.49 | 0.43 | 0.189 |

| 3-factor model | 1885.76 | 227 | 0.143 | 0.69 | 0.66 | 0.151 |

| 4-factor model | 797.35 | 224 | 0.085 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.063 |

| 5-factor model | 595.93 | 220 | 0.069 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.059 |

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Work intensification | 3.64 | 0.95 | ||||

| 2. Work addiction | 2.85 | 0.86 | 0.24 ** | |||

| 3. Seeking resources | 3.70 | 0.65 | −0.07 | 0.14 ** | ||

| 4. Crafting towards strengths | 3.75 | 0.66 | −0.08 | 0.13 * | 0.61 ** | |

| 5. Workplace well-being | 3.52 | 0.83 | −0.20 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.46 ** |

| Workplace Well-Being | SR | CTS | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | |||||||

| SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | |

| Gender | 0.088 | −0.042 | 0.082 | −0.029 | 0.073 | −0.024 | 0.074 | 0.004 | 0.069 | −0.013 | 0.070 | −0.082 |

| Age | 0.007 | −0.073 | 0.007 | −0.056 | 0.006 | −0.050 | 0.006 | −0.110 | 0.006 | −0.016 | 0.006 | 0.133 |

| Profession | 0.094 | −0.069 | 0.089 | −0.003 | 0.080 | −0.038 | 0.081 | −0.040 | 0.075 | 0.083 | 0.076 | 0.091 |

| Job level | 0.069 | −0.009 | 0.064 | −0.030 | 0.057 | 0.006 | 0.058 | −0.014 | 0.054 | −0.086 | 0.055 | −0.040 |

| WI | 0.046 | −0.211 *** (−0.199 ***) | 0.045 | −0.265 *** (−0.265 ***) | 0.040 | −0.233 *** (−0.228 ***) | 0.040 | −0.228 *** (−0.229 ***) | 0.038 | −0.074 (−0.088) | 0.038 | −0.090 (−0.094) |

| WA | 0.049 | 0.354 *** (0.355 ***) | 0.044 | 0.276 *** (0.283 ***) | 0.045 | 0.286 *** (0.292 ***) | 0.041 | 0.183 ** (0.170 **) | 0.042 | 0.167 ** (0.160 **) | ||

| WI * WA | 0.042 | 0.118 * (0.120 *) | 0.038 | 0.068 (0.072) | 0.039 | 0.057 (0.065) | 0.036 | 0.119 * (0.114 *) | 0.036 | 0.150 ** (0.141 **) | ||

| SR | 0.057 | 0.423 *** (0.425 ***) | ||||||||||

| CTS | 0.056 | 0.407 *** (0.393 ***) | ||||||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.039 | 0.162 | 0.333 | 0.318 | 0.039 | 0.051 | ||||||

| ΔR2 | 0.052 | 0.179 | 0.348 | 0.333 | 0.058 | 0.070 | ||||||

| F | 3.860 ** | 10.815 *** | 23.118 *** | 21.664 *** | 3.035 ** | 3.728 ** | ||||||

| Seeking Resources | Crafting towards Strengths | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | 95% CI | |||||||

| IE | SE | LLCI | ULCI | IE | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

| −1SD | −0.050 | 0.022 | −0.102 | −0.013 | −0.049 | 0.021 | −0.101 | −0.016 |

| +1SD | 0.002 | 0.025 | −0.045 | 0.053 | 0.006 | 0.022 | −0.033 | 0.054 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Xie, W.; Huo, L. How Can Work Addiction Buffer the Influence of Work Intensification on Workplace Well-Being? The Mediating Role of Job Crafting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134658

Li Y, Xie W, Huo L. How Can Work Addiction Buffer the Influence of Work Intensification on Workplace Well-Being? The Mediating Role of Job Crafting. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(13):4658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134658

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yue, Wei Xie, and Liang’an Huo. 2020. "How Can Work Addiction Buffer the Influence of Work Intensification on Workplace Well-Being? The Mediating Role of Job Crafting" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 13: 4658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134658

APA StyleLi, Y., Xie, W., & Huo, L. (2020). How Can Work Addiction Buffer the Influence of Work Intensification on Workplace Well-Being? The Mediating Role of Job Crafting. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(13), 4658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134658