Swedish Tennis Coaches’ Everyday Practices for Creating Athlete Development Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Focus Groups

2.2. Participants

2.3. Conducting the Focus Groups

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Club and Work Environment

We have six full-time coaches, four coaches for the juniors, one for competition juniors and one for adult coaching.(Coach 3)

We have three full-time employees, two part-time on 60 percent and a number of hourly coaches, about 10–15… it is difficult to have full-time coaches as the need for coaches varies a lot during the day and during the year… but the quality of coaching is definitely lowered since we cannot have more full-time coaches.(Coach 2)

We have many part-time, I am personally opposed to having part-time coaches, but always difficult with the economy... people only focus on the economy... it’s a long day to be part-time... don’t want to complain, but you don’t survive part-time…also difficult maintaining a common approach and high quality of coaching with too many part-time coaches... it is not ok.(Coach 8)

We have a full-time coach both Saturday and Sunday who is responsible for supporting the hourly coaches… so that we not only have 17-year-olds who are eating sandwiches and looking at their phone.(Coach 3)

I have no clear job description... is often about urgent needs, what is most urgent to solve... I sit on all chairs, hard to complete anything.(Coach 1)

There is no job description... I do it myself... Got one 23 years ago but there is no new one, it remains... I argue with the board... there is no updated work description...(Coach 11)

An ordinary day... check that no graffiti on the facilities, that it looks clean and fresh... if one of the coaches are sick and needs to be replaced... the phone on and “emergency” things happening... have a shop and cafe under management of the club that I am responsible for... doing court booking and member questions... then suddenly there is someone who wants to talk about his forehand.(Coach 1)

A lot of tasks that do not have to do with the tennis... sometimes I get worried about my health and well-being … I have worked seven days a week for a year... if I didn’t think it was so much fun doing this job I would have stopped long ago... but how long will I last?(Coach 10)

I always try to make sure we have a high quality in our training program…So if someone gets sick I usually fill in for that person rather than finding someone else…I have never taken a sick-day from work…At times this has even meant standing on the court with pneumonia or sinus infection.(Coach 12)

3.2. Competition Versus Economy

We have much fewer good juniors… have noticed a big difference in the last 10 years… there are fewer and fewer players who engage in a long-term commitment to competing.(Coach 5)

It has been the same trend for the last 10 years, the more successful you are in organizing internal club competitions the more people there are that are content with this and do not go on with their competition tennis. We have just over 100 juniors who in some way compete in our club but then on red, orange, green levels [softer balls and smaller courts] …” juice and cookie level” … Competition peaks around 11 years old but after that many starts dropping out.(Coach 2)

We have built up an environment in Swedish tennis where it is very difficult to get started playing competitions. It is required that you are so damn good before you start to compete. We have official competitions first when the boys and girls are 10 years old. In other sports you start earlier and more naturally. Many get stuck doing tennis lessons for three-four years and then drop out.(Coach 4)

Out of our competition juniors, it is probably only half of them that actually compete regularly. If you have played a match then you are suddenly a competition junior. We have 70–80 competition juniors I think or how many are there really?(Coach 12)

Before the juniors were in focus, now a lot of focus is instead placed on the adults. They are often very demanding and take up a lot of time and energy from us coaches.(Coach 6)

In the past we had 400 juniors in our club, where 90 percent of them only played once a week and only for 45 min. It was like a factory, so we scaled back, expanded our facilities and hired more coaches, but now it is completely full again so we have to come up with magic again.(Coach 3)

3.3. Everyday Practices for Athlete Development

The big focus for me is to work from below... work meticulously already in tennis school... we can’t have an 18-year-old who serves with the wrong grip... we work a lot with joint planning at younger ages, then when they are older more individually...(Coach 9)

We work clearly with six different levels… for example blue, red, orange and green levels… different checkpoints along the way that we have for all children to see where they are in their development for example forehand, footwork, follow-up…. this to have the best opportunities to develop into a good competition player…(Coach 11)

I work a lot with the collaboration between club and high school to free up time for tennis for the high school students who have high ambitions... I also work with sponsorship to be able to provide them with money to continue to travel and participate in competitions...(Coach 6)

We have from the beginning a system that is based on playing matches, so that the players get used to playing matches but in a nicer format, such as the “Friday game” and now also Saturday matches which are exchanges with other clubs nearby … The whole thing is about playing a lot of matches so you get used to it.(Coach 7)

My work with this is a lot on the weekends, participate at various interclub games and tournaments, where I can follow the juniors’ matches… I often work six days a week or more…. I also follow interclub games and competitions at home.(Coach 9)

They grow tremendously on these competition trips... the juniors need to feel that it is their sport... too much nagging from the parents sometimes... we do not bring parents on any competitions and camps... these competitions and trips important for the players who have participated…but it also raises the average level for everyone else in the club...so has sort of a flow-on effect.(Coach 6)

I travel a bit with the 12–13-year old’s… want to see them playing proper matches… when you see a good even tennis match there is a lot that you can learn and bring home… but I cannot be gone 4–5 days from the club very often, it just doesn’t work.(Coach 11)

Time thieves do not allow time for player development... player development is done in evenings and weekends, one must set aside time to hide away and work on this otherwise it just does not happen.(Coach 1)

There is not enough time for all the administrative tasks... emails you have to answer… but not fully develop the younger players…. difficult with individual support and development… difficult to plan ahead and have a plan for each player... wish you had more time for it... difficult to follow up training diaries and match reports…(Coach 5)

3.4. Goals for Athlete Development

We have an explicit goal of enhancing competition players.(Coach 2)

Goals…. Well we are a club for everyone, everyone is allowed to participate... we want to be able to produce good juniors nationally... we want teams in the highest leagues, but what are the highest leagues?(Coach 4)

Goals, well to produce as good tennis players as we can produce... but no requirement for having, for example, two international players... we work with the big masses hoping some of them will turn out to be good...(Coach 7)

No direct goals... you work up to 18 years old and then it ends... no short-term or long-term goals, there are no goals in the club other than what is stated on the website.(Coach 10)

A competition situation arises … Should we prioritize economy or competition? Then economy always wins.(Coach 13)

Certainly, we have an explicit goal of producing competition players, but dilemma with the board’s interest, do they have knowledge of what it takes to make this journey?(Coach 2)

For the board, the economic thing is by far the most important…. very little talk about the competition bit…. when I write the head coach report, I try to highlight the competition juniors a little extra because they did well but it is noticed very little… there is no communication or understanding what is required to be a competition player… we have different experiences of competitive tennis... I have a good understanding of what is required... I have traveled a lot... But have difficulty communicating to those who do not understand or have that interest.(Coach 12)

The number of juniors is greater than ever... but what do we do with them?(Coach 6)

Tennis is about playing matches... last year we had a club champs for 9–12-year old’s, most of them did not even know the rules, we had to have an umpire for it to work...(Coach 7)

We have no direct plan... you work up to 18 years then it ends... big numbers and big business between 6–11 years then a sudden hump... most of them drop out.(Coach 9)

3.5. Collaboration and Communication

We can get much better in Swedish tennis at cooperation... work over club boundaries more... must drop this whole thing that this is my club... we have to be more prestigeless…must be more realistic what we can do ourselves for the greater good of the juniors...(Coach 6)

The fact that we do not have a regional centre is not good... we need somewhere where coaches and players can train together and communicate with each other.(Coach 1)

We desperately need regional and national centres... where coaches and players can meet up say once a month to train and collaborate.(Coach 8)

As it looks now, each club sits in their own office and re-invents the wheel, why does not the association send out all the expertise that exists…centrally providing content and material what to work with at different ages, as they do for example in France.... if you do not work with this, you lose your funding…but no everyone still sits in their own office and runs their own race... makes us all lose a lot of time and resources that could instead be put into time player development.(Coach 7)

There are many highly talented and experienced coaches in Sweden who can contribute knowledge and skills…would be good with guidelines…not exactly followed but as a common starting point.(Coach 1)

Now we all develop our own checkpoints, it would be better for the national association to develop it... Hire a good coach who, for example, develops an under 10 year olds program that then goes out to other clubs... One region already has its own tennis technique handbook... would be better if we all had a common model... Then of course we can develop it ourselves in our own context... But optimal if it came from the top where the most knowledgeable people are.(Coach 12)

4. Discussion

4.1. Management and Coaches

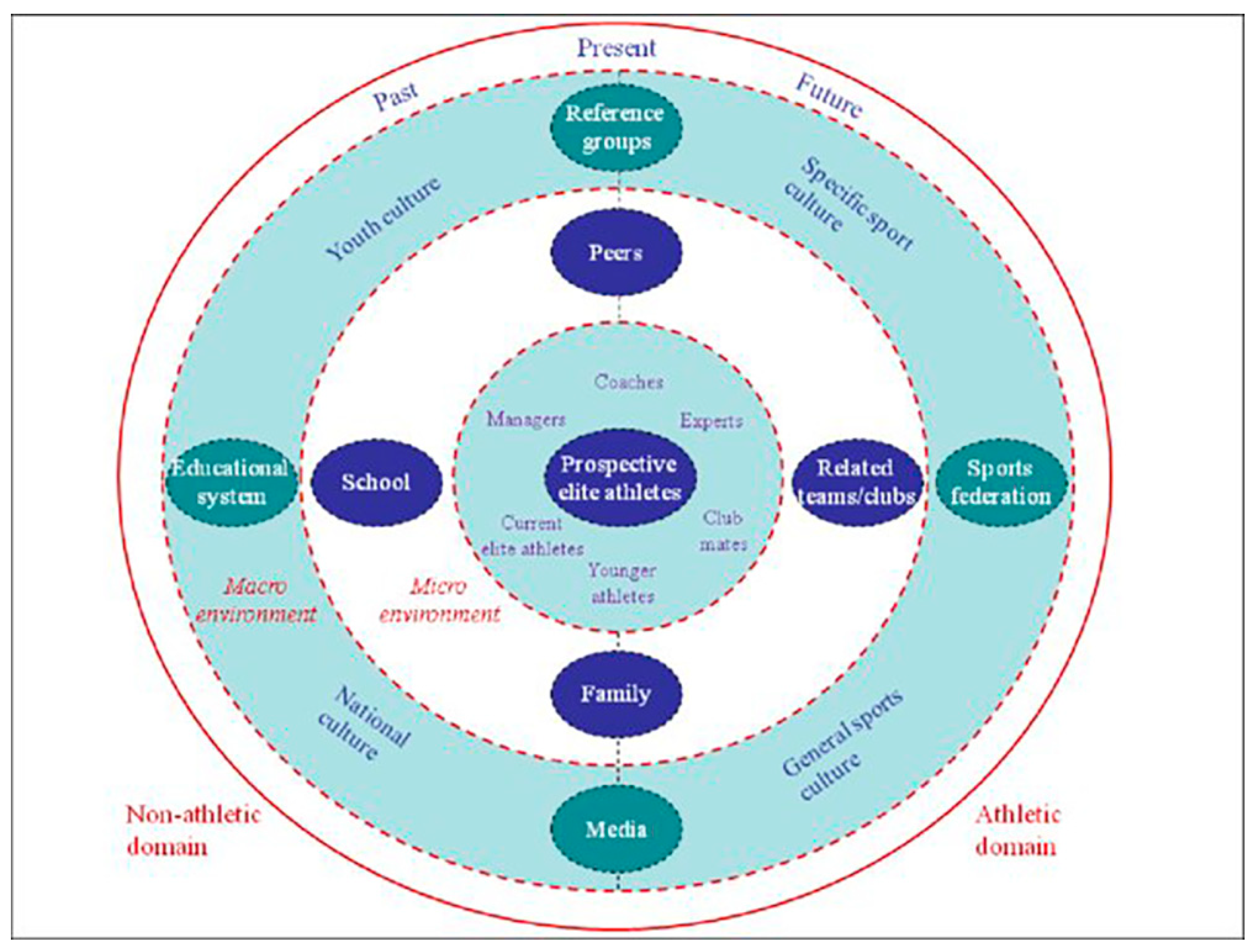

4.2. The Immediate Surrounding and Developing Environment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bloom, B.S. Developing Talent in Young People; Ballantine Books: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Rathunde, K.; Whalen, S. Talented Teenagers: The Roots of Success and Failure; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Starkes, J.L.; Ericsson, K.A. Expert Performance in Sport: Advances in Research on Sport Expertise; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pankhurst, A.; Collins, D.; MacNamara, A. Talent development: Linking the stakeholders to the process. J. Sports Sci. 2013, 31, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martindale, R.J.J.; Collins, D.; Daubney, J. Talent development: A guide for practice and research within sport. Quest 2005, 57, 353–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.; Bagats, S.; Busch, D.; Strauss, B.; Schorer, J. Training differences and selection in a talent identification system. Talent Dev. Excel. 2012, 4, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Fahlström, P.G. To Identify and Develop Talents—A Study of the Specialist Sporting Federations’ Talent Programmes; Swedish Sports Confederation: Stockholm, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J. Sports Talent: How to Identify and Develop Outstanding Athletes; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, M.; Davidson, J.; Sloboda, J. Innate talents: Reality or myth? Behav. Brain Sci. 1998, 21, 399–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagne, F. Academic talent development and the equity issue in gifted education. Talent Dev. Excel. 2011, 3, 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, D.T.; Naughton, G.A.; Torode, M. Predictability of physiological testing and the role of maturation in talent identification for adolescent team sports. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2006, 9, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreiros, A.; Côté, J.; Fonseca, A.M. From early to adult sport success: Analysing athletes’ progression in national squads. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2014, 14 (Suppl. 1), S178–S182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, J.; Schorer, J.; Wattie, N. Compromising Talent: Issues in Identifying and Selecting Talent in Sport. Quest 2018, 70, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davids, K.; Baker, J. Genes, environment, and sport performance: Why the nature-nurture dualism is no longer relevant. Sports Med. 2007, 37, 961–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahlström, P.G.; Gerrevall, P.; Glemne, M.; Linnér, S. The Roads to the National Team. About Swedish Elite Athletes’ Sport Choices and Specialisation; Swedish Sports Confederation: Stockholm, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Storm, L.K.; Henriksen, C.; Krogh-Christensen, M. Specialization pathways among elite Danish athletes: A look at the developmental model of sport participation from a cultural perspective. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 2012, 43, 199–222. [Google Scholar]

- Storm, L.K. Coloured by Culture. Talent Development in Scandinavian Elite Sport as Seen from a Cultural Perspective. Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Sports Science and Clinical Biomechanics Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am. Psychol. 1977, 32, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Strachan, L.; Côté, J.; Deakin, J. A new view: Exploring positive youth development in elite sport contexts. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. 2009, 3, 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, R. The Road to the National Team: A Retrospective Study of Successful Youth in Seven Sports. Ph.D. Thesis, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser-Thomas, J.L.; Coté, J.; Deakin, J. Youth sport programs: An avenue to foster positive youth development. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2005, 10, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustsson, C. Young Athletes’ Experiences of Parental Pressure. Ph.D. Thesis, Karlstad University, Karlstad, Sweden, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Eliasson, I. In Different Sporting Worlds: Youth, Leaders and Parents in Girls’ and Boys’ Soccer. Ph.D. Thesis, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, T. Sport: It’s a family affair. In Coaching Children in Sport; Lee, M., Ed.; E & FN Spon: London, UK, 1993; pp. 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, T.; Potrac, P.; McKenzie, A. Evaluating and reflecting upon a coach education initiative: The Code of rugby. Sport Psychol. 2006, 20, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culver, D.; Trudel, P. Clarifying the concept of communities of practice in sport. Int. J. Sport Sci. Coach. 2006, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, W.; Trudel, P. Role of the coach: How model youth team sport coaches frame their roles. Sport Psychol. 2004, 18, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denison, J.; Mills, J.; Jones, L. Effective coaching as a modernist formation. In The Routledge Handbook of Sports Coaching; Potrac, P., Gilbert, W., Denison, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 388–399. [Google Scholar]

- Mallet, C.J.; Rynne, S.B.; Dickens, S. Developing high performance coaching craft through work and study. In The Routledge Handbook of Sports Coaching; Potrac, P., Gilbert, W., Denison, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 463–475. [Google Scholar]

- Finn, J.; McKenna, K.J. Coping with academy-to-first-team transitions in elite English male team sports: The coaches’ perspective. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2010, 5, 257–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tushman, M.L.; Anderson, P. Technological discontinuities and organizational environments. Adm. Sci. Q. 1986, 31, 439–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, K.A.; Prietula, M.J.; Cokely, E.T. The making of an expert. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007, 2007, 115–121. [Google Scholar]

- Alfermann, D.; Stambulova, N. Career transitions and career termination. In Handbook of Sport Psychology; Tennenbaum, G., Ecklund, R.C., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 712–733. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen, K. The Ecology of Talent Development in Sport: A Multiple Study of Successful Athletic Talent Development Environments in Scandinavia. Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Sports Science and Clinical Biomechanics Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fahlström, P.G.; Glemne, M.; Linnér, S. Good Sporting Development Environments: A Study of Environments that Are Successful in Developing Elite Athletes; Swedish Sports Confederation: Stockholm, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, J.; Young, B. 20 years later: Deliberate practice and the development of expertise in sport. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2014, 7, 135–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivarsson, A.; Stenling, A.; Fallby, J.; Johnson, U.; Borg, E.; Johansson, G. The predictive ability of the talent development environment on youth elite football players’ well being. A person-centred approach. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 16, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, C.J.; Pyun, D.Y. Talent development environmental factors in sport: A review and taxonomic classification. Quest 2014, 66, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gerdin, G.; Hedberg, M.; Hageskog, C.-A. Relative Age Effect in Swedish Male and Female Tennis Players Born in 1998–2001. Sports 2018, 6, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, K. A Profession under Development? A Survey of Tennis Coaches’ Everyday Practices and Working Conditions. Unpublished Degree Thesis, Linnaeus University, Växjö, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S. InterViews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gerdin, G. Boys Will Be Boys? Gendered Bodies, Spaces and dis/Pleasures in Physical Education. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swedish Research Council. Research Ethical Principles in Social Science Research; Swedish Research Council: Stockholm, Sweden, 2002.

- Swedish Ethical Review Act. Law (2003:460) about Ethical Approval for Research Involving Human Participants; The Swedish Government: Stockholm, Sweden, 2004.

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-item Checklist for Interviews and Focus Groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Coach/Club | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full-time coaches | 2 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Members | 600 | 860 | 1100 | 1100 | 600 | 1000 | 1800 | 3000 | 800 | 300 | 1300 | 7000 | 400 |

| Juniors | 300 | 300 | 400 | 450 | 190 | 280 | 300 | 600 | 300 | 180 | 500 | 300 | 140 |

| Competition juniors | 50 | 30 | 60 | 20 | 20 | 15 | 50 | 70 | 30 | 20 | 80 | 30 | 10 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gerdin, G.; Fahlström, P.G.; Glemne, M.; Linnér, S. Swedish Tennis Coaches’ Everyday Practices for Creating Athlete Development Environments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4580. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124580

Gerdin G, Fahlström PG, Glemne M, Linnér S. Swedish Tennis Coaches’ Everyday Practices for Creating Athlete Development Environments. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(12):4580. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124580

Chicago/Turabian StyleGerdin, Göran, Per Göran Fahlström, Mats Glemne, and Susanne Linnér. 2020. "Swedish Tennis Coaches’ Everyday Practices for Creating Athlete Development Environments" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 12: 4580. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124580

APA StyleGerdin, G., Fahlström, P. G., Glemne, M., & Linnér, S. (2020). Swedish Tennis Coaches’ Everyday Practices for Creating Athlete Development Environments. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4580. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124580