How Does Perfectionism Influence the Development of Psychological Strengths and Difficulties in Children?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedure

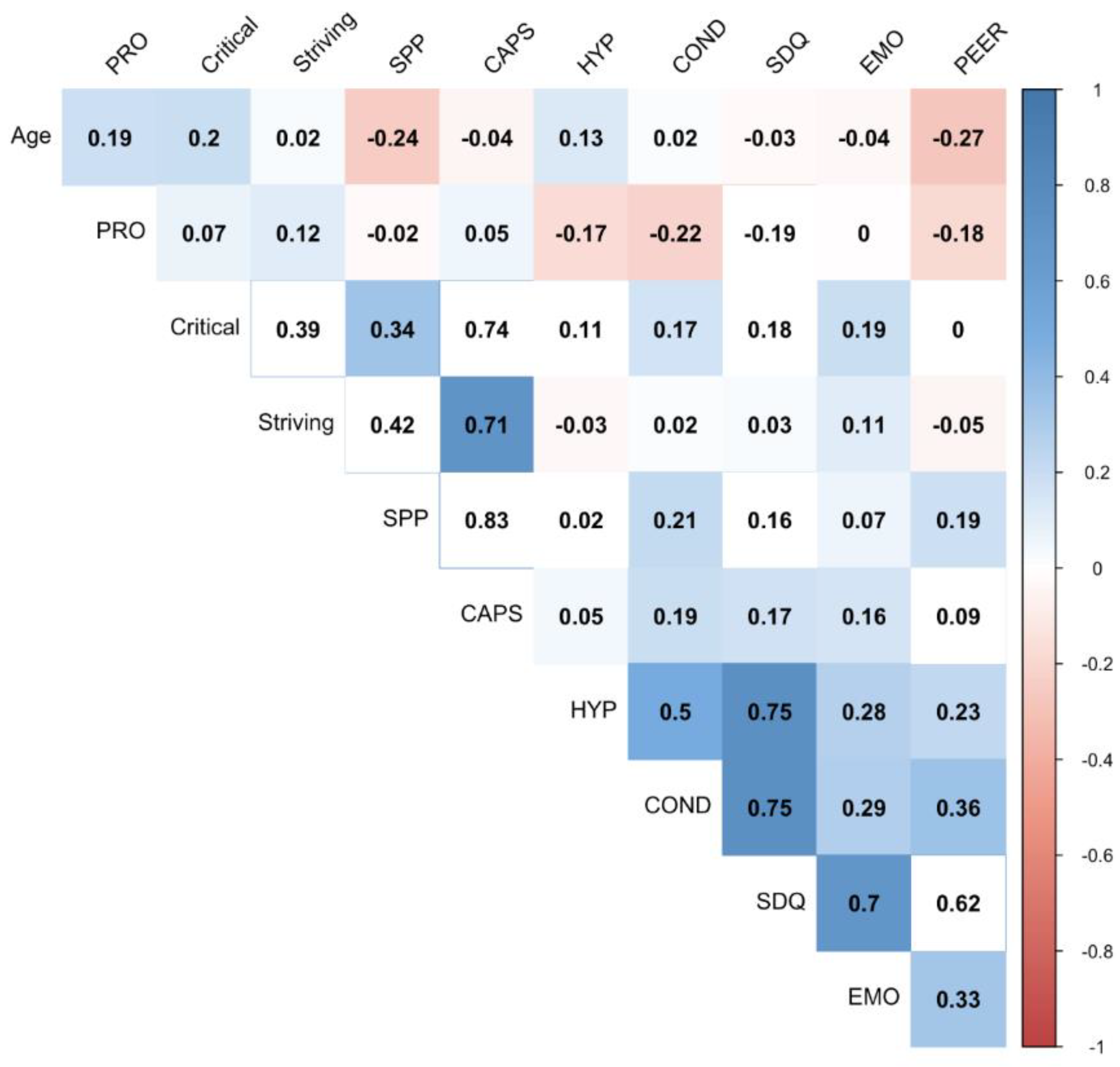

2.4. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Data of the Sample

3.2. Differences in CAPS-S by Perfectionism Level

3.3. Descriptive Data on Age and Gender in Perfectionism

3.4. Descriptive Data on Strengths and Difficulties in Perfectionism

3.5. Regression Analyses Predicting Child Strengths and Difficulties

3.5.1. Emotional Problems

3.5.2. Conduct Problems

3.5.3. Hyperactivity

3.5.4. Peer Problems

3.5.5. Prosocial Behavior

3.5.6. Total Difficulties

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Flett, G.; Hewitt, P. Perfectionism: Theory, Research, and Treatment; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Stoeber, J. The psychology of perfectionism: Critical issues, open questions, and future directions. In The Psychology of Perfectionism: Theory, Research, Applications; Stoeber, J., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeber, J.; Childs, J. Perfectionism. In Encyclopedia of Adolescence; Levesque, R., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 2053–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oros, L. Medición del perfeccionismo infantil: Desarrollo y validación de una escala para niños de 8 a 13 años de edad. Rev. Iberoam. Diagn. Eval. Psicol. 2003, 16, 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Oros, L. Implicaciones del perfeccionismo infantil sobre el bienestar psicológico: Orientaciones para el diagnóstico y la práctica clínica. An. Psicol. Ann. Psychol. 2005, 21, 294–303. [Google Scholar]

- Flett, G.L.; Hewitt, P.L. Reflections on three decades of research on multidimensional perfectionism: An introduction to the special issue on further advances in the assessment of perfectionism. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2020, 38, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, P.L.; Caelian, C.F.; Flett, G.L.; Sherry, S.B.; Collins, L.; Flynn, C.A. Perfectionism in children: Associations with depression, anxiety, and anger. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2002, 32, 1049–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieling, P.J.; Israeli, A.L.; Antony, M.M. Is perfectionism good, bad, or both? Examining models of the perfectionism construct. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2004, 36, 1373–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, B.C.; Moore, A.M.; Koestner, R. Distinguishing self-oriented perfectionism-striving and self-oriented perfectionism-critical in school-aged children: Divergent patterns of perceived parenting, personal affect and school performance. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 113, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limburg, K.; Watson, H.J.; Hagger, M.S.; Egan, S.J. The relationship between perfectionism and psychopathology: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 73, 1301–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, S.J.; Wade, T.D.; Shafran, R. Perfectionism as a transdiagnostic process: A clinical review. Transdiagn. Transtheor. Approaches 2011, 31, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eum, K.; Rice, K.G. Test anxiety, perfectionism, goal orientation, and academic performance. Anxiety Stress. Coping 2011, 24, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, J.M.; Inglés, C.J.; Vicent, M.; Gonzálvez, C.; Gómez-Núnez, M.I.; Poveda-Serra, P. Perfeccionismo durante la infancia y la adolescencia. Análisis bibliométrico y temático (2004–2014). Rev. Iberoam. Psicol. Salud 2016, 7, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, L.M.; Valor-Segura, I.; García-Cueto, E.; Pedrosa, I.; Llanos, A.; Lozano, L. Relationship between child perfectionism and psychological disorders. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flett, G.L.; Panico, T.; Hewitt, P.L. Perfectionism, type A behavior, and self-efficacy in depression and health symptoms among adolescents. Curr. Psychol. 2011, 30, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.M.; Saklofske, D.H.; Yan, G.; Sherry, S.B. Perfectionistic strivings and perfectionistic concerns interact to predict negative emotionality: Support for the tripartite model of perfectionism in Canadian and Chinese university students. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 81, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-Fernández, L.M.; García-Cueto, E.; Martín-Vázquez, M.; Lozano-González, L. Development and validation of the Child Perfectionism Inventory (IPI). Psicothema 2012, 24, 149–155. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, D.A.; Jacquez, F.M.; Maschman, T.L. Social origins of depressive cognitions: A longitudinal study of self-perceived competence in children. Cognit. Ther. Res. 2001, 25, 377–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flett, G.; Hewitt, P.; Boucher, D.; Davidson, L.; Munro, I. The Child-Adolescent Perfectionism Scale: Development, Validation, and Association with Adjustment. Unpublished Manuscript; University of British Columbia: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Flett, G.L.; Hewitt, P.L.; Besser, A.; Su, C.; Vaillancourt, T.; Boucher, D.; Munro, Y.; Davidson, L.A.; Gale, O. The child–adolescent perfectionism scale: Development, psychometric properties, and associations with stress, distress, and psychiatric symptoms. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2016, 34, 634–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicent, M.; Inglés, C.J.; Sanmartín, R.; Gonzálvez, C.; Delgado, B.; García-Fernández, J.M. Spanish validation of the child and adolescent perfectionism scale: Factorial invariance and latent means differences across sex and age. Brain Sci. 2019, 9, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douilliez, C.; Hénot, E. Adolescent perfection measures: Validation of two French questionnaires. Can. J. Behav. Sci. Can. Sci. Comport. 2013, 45, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicent, M.; Aparicio-Flores, M.P.; Inglés, C.J.; Gómez-Núñez, M.I.; Fernández-Sogorb, A.; Aparisi-Sierra, D. Perfeccionismo infantil: Diferencias en función del sexo y la edad. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 3, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- San Martín, N.L.; Luengo, M.P. Diferencias en ansiedad escolar, autoestima y perfeccionismo en función del nivel escolar y el sexo en estudiantes chilenos de educación primaria. Rev. Reflex. Investig. Educ. 2018, 1, 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Maia, B.R.; Soares, M.J.; Pereira, A.T.; Marques, M.; Bos, S.C.; Gomes, A.; Valente, J.; Azevedo, M.H.; Macedo, A. Affective state dependence and relative trait stability of perfectionism in sleep disturbances. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2011, 33, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrath, D.S.; Sherry, S.B.; Stewart, S.H.; Mushquash, A.R.; Allen, S.L.; Nealis, L.J.; Sherry, D.L. Reciprocal relations between self-critical perfectionism and depressive symptoms: Evidence from a short-term, four-wave longitudinal study. Can. J. Behav. Sci. Can. Sci. Comport. 2012, 44, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherry, S.B.; MacKinnon, A.L.; Fossum, K.-L.; Antony, M.M.; Stewart, S.H.; Sherry, D.L.; Nealis, L.J.; Mushquash, A.R. Perfectionism, discrepancies, and depression: Testing the perfectionism social disconnection model in a short-term, four-wave longitudinal study. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2013, 54, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oros, L.B.; Iuorno, O.; Serppe, M. Child perfectionism and its relationship with personality, excessive parental demands, depressive symptoms and experience of positive emotions. Span. J. Psychol. 2017, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, L.M.; Valor-Segura, I.; Lozano, L. Could a perfectionism context produce unhappy children? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 80, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.H.; Yap, K.; Francis, A.J.P.; Schuster, S. Perfectionism and its relationship with anticipatory processing in social anxiety. Aust. J. Psychol. 2014, 66, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, M.; Chasson, G.S.; Wetterneck, C.T.; Hart, J.M.; Björgvinsson, T. Perfectionism dimensions as predictors of symptom dimensions of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Bull. Menn. Clin. 2014, 78, 140–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, J.; Shu, C.Y.; Hoiles, K.J.; Clarke, P.J.F.; Watson, H.J.; Dunlop, P.D.; Egan, S.J. Perfectionism is associated with higher eating disorder symptoms and lower remission in children and adolescents diagnosed with eating disorders. Eat. Behav. 2018, 30, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicent, M.; Gonzálvez, C.; Sanmartín, R.; García-Fernández, J.M.; Inglés, C.J. Perfeccionismo socialmente prescrito y afecto en la infancia. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 1, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Stoeber, J.; Noland, A.B.; Mawenu, T.W.N.; Henderson, T.M.; Kent, D.N.P. Perfectionism, social disconnection, and interpersonal hostility: Not all perfectionists don’t play nicely with others. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 119, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanVoorhis, C.R.W.; Morgan, B.L. Understanding power and rules of thumb for determining sample sizes. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2007, 3, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R. Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2001, 40, 1337–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortuño-Sierra, J.; Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; Inchausti, F.; Sastre i Riba, S. Evaluación de dificultades emocionales y comportamentales en población infanto-juvenil: El Cuestionario de capacidades y dificultades (SDQ). Pap. Psicól. 2016, 37, 14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Beasley, T.M.; Schumacker, R.E. Multiple regression approach to analyzing contingency tables: Post hoc and planned comparison procedures. J. Exp. Educ. 1995, 64, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behaviors Science, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Akoglu, H. User’s guide to correlation coefficients. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 18, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; Chang, W. Ggplot2: An implementation of the Grammar of Graphics. Book Abstr. 2009. Available online: http://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/.

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R (Version 1.1. 453); Computer Software: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra, E.E. Relationship of Perfectionism and Gender to Academic Performance and Social Functioning in Adolescents. Ph.D.Thesis, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Saboonchi, F.; Lundh, L.-G. Perfectionism, anger, somatic health, and positive affect. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2003, 35, 1585–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeber, J.; Otto, K.; Dalbert, C. Perfectionism and the big five: Conscientiousness predicts longitudinal increases in self-oriented perfectionism. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2009, 47, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Perfectionism | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | High (n = 88) | Medium (n = 156) | Low (n = 75) | F3/χ2 4 | p5 | Cramer’s V | ||

| Female N (%) | 167 (52.4) | 46 (61.3) | 80 (51.3) | 41 (46.6) | 3.66 | 0.16 | - | |

| Age (years) M 1 (SD) 2 | 9.38 (1.15) | 9.42 (1.25) | 9.31 (1.14) | 9.45 (1.03) | 0.45 | 0.63 | - | |

| Age (years) N (%) | ||||||||

| 7 | 10 (3.1) | 2 (2.3) | 6 (3.8) | 2 (2.7) | 15.81 | 0.04 | 0.15 | |

| 8 | 77 (24.1) | 26 (29.5) | 38 (24.4) | 13 (17.3) | ||||

| 9 | 81 (25.4) | 19 (21.6) | 42 (26.9) | 20 (26.7) | ||||

| 10 | 85 (26.6) | 15 (17) | 41 (26.3) | 29 (38.7) | ||||

| 11 | 66 (20.7) | 26 (29.5) | 29 (18.6) | 11 (14.7) | ||||

| Nationality | ||||||||

| Spanish | 311 (97.8) | 86 (97.7) | 151 (97.4) | 74 (98.7) | 0.36 | 0.83 | ||

| Other | 8 (2.2) | 2 (2.3) | 4 (2.6) | 1 (1.3) | ||||

| Number of siblings (years) M 1 (SD) 2 | 1.01 (0.72) | 1.05 (0.72) | 0.97 (0.74) | 1.05 (0.76) | 0.49 | 0.61 | - | |

| Number of siblings N (%) | ||||||||

| 0 | 62 (19.4) | 13 (14.8) | 34 (21.8) | 15 (20) | 10.36 | 0.24 | - | |

| 1 | 209 (65.5) | 63 (71.6) | 101 (64.7) | 45 (60) | ||||

| 2 | 35 (11) | 7 (8) | 16 (10.3) | 12 (16) | ||||

| 3 | 9 (2.8) | 5 (5.7) | 2 (1.3) | 2 (2.7) | ||||

| 4 | 4 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.9) | 1 (1.3) | ||||

| School level N (%) | ||||||||

| 3 | 75 (23.5) | 27 (30.7) | 36 (23.1) | 12 (16) | 14.83 | 0.02 | 0.15 | |

| 4 | 86 (27) | 17 (19.3) | 47 (30.1) | 22 (29.3) | ||||

| 5 | 80 (25.1) | 16 (18.2) | 37 (23.7) | 27 (36) | ||||

| 6 | 78 (24.5) | 28 (31.8) | 36 (23.1) | 14 (18.7) | ||||

| CAPS-S Items | Perfectionism | F1 | p2 | Post Hoc 3 | Partial Eta Square | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | High (n = 88) | Medium (n = 156) | Low (n = 75) | |||||

| SOP-Striving 7 | ||||||||

| 1. I try to be perfect in everything I do. | 3.61 (1.34) | 4.36 (0.98) | 3.75 (1.21) | 2.45 (1.20) | 57.67 | ≤0.001 | H 4 > M 5 H > L 6 M > L | 0.26 |

| 2. I want to be the best at everything I do. | 2.97 (1.46) | 4.14 (1.01) | 2.93 (1.33) | 1.66 (0.94) | 91.49 | ≤0.001 | H > M H > L M > L | 0.36 |

| 4. I feel that I have to do my best all the time. | 4.47 (0.95) | 4.80 (0.58) | 4.55 (0.86) | 3.93 (1.23) | 19.89 | ≤0.001 | H > L M > L | 0.11 |

| 6. I always try for the top score on a test. | 4.67 (0.81) | 4.95 (0.25) | 4.71 (0.70) | 4.26 (1.21) | 16.17 | ≤0.001 | H > L M > L | 0.09 |

| SOP-Critical 8 | ||||||||

| 11. I get mad at myself when I make a mistake. | 3.34 (1.54) | 4.19 (1.18) | 3.33 (1.50) | 2.37 (1.44) | 33.73 | ≤0.001 | H > M H > L M > L | 0.17 |

| 14. I get upset if there is even one mistake in my work. | 2.26 (1.51) | 3.29 (1.62) | 2.10 (1.38) | 1.37 (0.78) | 43.24 | ≤0.001 | H > M H > L M > L | 0.21 |

| 20. Even when I pass, I feel that I have failed if I didn’t get one of the highest marks in the class. | 2.36 (1.56) | 3.54 (1.56) | 2.19 (1.41) | 1.34 (0.79) | 56.77 | ≤0.001 | H > M H > L M > L | 0.26 |

| 22. I cannot stand to be less than perfect. | 2.37 (1.53) | 3.52 (1.54) | 2.22 (1.38) | 1.33 (0.75) | 57.93 | ≤0.001 | H > M H > L M > L | 0.26 |

| SPP 9 | ||||||||

| 5. There are people in my life who expect me to be perfect. | 3.18 (1.59) | 4.34 (1.01) | 3.20 (1.49) | 1.78 (1.20) | 76.79 | ≤0.001 | H > M H > L M > L | 0.32 |

| 8. My family expects me to be perfect. | 2.92 (1.59) | 4.22 (1.16) | 2.86 (1.45) | 1.50 (0.89) | 93.81 | ≤0.001 | H > M H > L M > L | 0.37 |

| 10. People expect more from me than I am able to give. | 3.06 (1.57) | 3.96 (1.37) | 2.94 (1.51) | 2.28 (1.41) | 28.35 | ≤0.001 | H > M H > L M > L | 0.15 |

| 13. Other people always expect me to be perfect. | 2.72 (1.60) | 4.09 (1.22) | 2.59 (1.48) | 1.37 (0.74) | 92.95 | ≤0.001 | H > M H > L M > L | 0.37 |

| 17. My teachers expect my work to be perfect. | 3.50 (1.43) | 4.21 (1.06) | 3.58 (1.34) | 2.49 (1.42) | 36.51 | ≤0.001 | H > M H > L M > L | 0.18 |

| SOP-Striving (6–20) | 15.73 (3.14) | 18.27 (1.67) | 15.95 (2.45) | 12.32 (2.66) | 134.47 | ≤0.001 | H > M H > L M > L | 0.46 |

| SOP-Critical (4–20) | 10.35 (4.31) | 14.55 (3.57) | 9.86 (3.33) | 6.42 (2.09) | 137.23 | ≤0.001 | H > M H > L M > L | 0.46 |

| SPP (5–25) | 15.40 (5.50) | 20.84 (3.16) | 15.19 (4.30) | 9.44 (2.89) | 191.04 | ≤0.001 | H > M H > L M > L | 0.54 |

| CAPS-S 10 (19–65) | 41.49 (10.01) | 53.67 (4.44) | 41.01 (4.02) | 28.18 (4.22) | 751.38 | ≤0.001 | H > M H > L M > L | 0.82 |

| Gender | Age | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls (n = 167) | Boys (n = 152) | t-test | p 5 | d 6 | 7–9 years (n = 168) | 10–11 years (n = 151) | t-test | p 5 | d 6 | |

| SOP-Striving 1 | 15.41 (3.13) | 16.09 (3.13) | 1.91 | 0.05 | 0.21 | 15.73 (2.98) | 15.74 (3.33) | −0.01 | 0.99 | - |

| SOP-Critical 2 | 9.80 (4.10) | 10.94 (4.46) | 2.37 | 0.01 | 0.26 | 9.75 (4.24) | 11.01 (4.30) | −2.65 | 0.008 | 0.29 |

| SPP 3 | 14.78 (5.44) | 16.07 (5.50) | 2.10 | 0.03 | 0.23 | 16.66 (5.38) | 13.99 (5.31) | 4.45 | 0.001 | 0.49 |

| CAPS-S 4 | 40.01 (9.85) | 43.11 (9.97) | 2.79 | 0.005 | 0.31 | 42.15 (9.45) | 40.7 (10.58) | 1.24 | 0.21 | - |

| Perfectionism | F | p | Post Hoc 3 | Partial Eta Square | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | High (n = 88) | Medium (n = 156) | Low (n = 75) | |||||

| Emotional problems | 2.71 (2.31) | 2.96 (2.51) | 2.85 (2.25) | 2.10 (2.11) | 3.45 | 0.03 | H 1 > L 2 | 0.02 |

| Conduct problems | 2.41 (1.93) | 2.75 (2.06) | 2.44 (1.87) | 1.93 (1.84) | 3.72 | 0.02 | H > L | 0.02 |

| Hyperactivity | 4.12 (2.35) | 4.05 (2.32) | 4.25 (2.48) | 3.92 (2.10) | 0.56 | 0.57 | - | - |

| Peer problems | 1.49 (1.58) | 1.55 (1.73) | 1.49 (1.63) | 1.44 (1.28) | 0.11 | 0.89 | - | - |

| Prosocial behavior | 8.36 (1.57) | 8.59 (1.57) | 8.28 (1.65) | 8.29 (1.37) | 1.20 | 0.30 | - | - |

| Total difficulties | 10.74 (5.80) | 11.32 (6.15) | 11.05 (5.89) | 9.40 (4.97) | 2.71 | 0.06 | - | - |

| Predictor Variables | B2 | 95% CI 3 (B) | β4 | t Statistic 5 | p-Value 6 | ΔR2 7 | Adj.R2 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV 1: Emotional symptoms | |||||||

| Step 1 | 0.25 | 0.77 | 0.002 | −0.005 | |||

| Constant | 3.42 | 1.30, 5.53 | 3.18 | 0.002 | |||

| Gender | −0.08 | −0.59, 0.43 | −0.01 | −0.30 | 0.75 | ||

| Age | −0.07 | −0.29, 0.15 | −0.03 | −0.62 | 0.53 | ||

| Step 2 | 2.90 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.03 | |||

| Constant | 2.88 | 0.27, 5.48 | 2.17 | 0.03 | |||

| Gender | 0.05 | −0.45, 0.56 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.82 | ||

| Age | −0.18 | −0.41, 0.05 | −0.09 | −1.49 | 0.13 | ||

| SOP-Striving 9 | 0.04 | −0.05, 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.88 | 0.37 | ||

| SOP-Critical 10 | 0.11 | 0.05, 0.17 | 0.20 | 3.17 | <0.001 | ||

| SPP 11 | −0.01 | −0.07, 0.03 | −0.04 | −0.69 | 0.49 | ||

| DV1: Conduct problems | |||||||

| Step 1 | 3.96 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | |||

| Constant | 2.33 | 0.59, 4.08 | 2.63 | 0.009 | |||

| Gender | −0.60 | −1.02, −0.17 | −0.15 | −2.79 | 0.006 | ||

| Age | 0.04 | −0.14, 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.44 | 0.65 | ||

| Step 2 | 5.99 | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.07 | |||

| Constant | 1.27 | −0.85, 3.40 | 1.17 | 0.24 | |||

| Gender | −0.50 | −0.91, −0.08 | −0.12 | −2.36 | 0.01 | ||

| Age | 0.10 | −0.09, 0.29 | 0.06 | 1.04 | 0.29 | ||

| SOP-Striving 9 | −0.08 | −0.16, −0.01 | −0.14 | −2.25 | 0.02 | ||

| SOP-Critical 10 | 0.05 | −0.005, 0.10 | 0.11 | 1.79 | 0.07 | ||

| SPP 11 | 0.08 | 0.03, 0.12 | 0.23 | 3.59 | <0.001 | ||

| DV: Hyperactivity | |||||||

| Step 1 | 6.51 | 0.002 | 0.04 | 0.03 | |||

| Constant | 1.82 | −0.28, 3.92 | 1.70 | 0.09 | |||

| Gender | −0.69 | −1.20, −0.18 | −0.14 | 2.67 | 0.008 | ||

| Age | 0.28 | 0.06, 0.50 | 0.14 | 2.51 | 0.01 | ||

| Step 2 | 3.47 | 0.004 | 0.05 | 0.03 | |||

| Constant | 2.34 | −0.29, 4.97 | 1.74 | 0.08 | |||

| Gender | −0.66 | −1.18, −0.14 | −0.14 | −2.52 | 0.01 | ||

| Age | 0.27 | 0.03, 0.51 | 0.13 | 2.22 | 0.02 | ||

| SOP-Striving 9 | −0.07 | −0.17, 0.01 | −0.10 | −1.66 | 0.09 | ||

| SOP-Critical 10 | 0.05 | −0.01, 0.12 | 0.09 | 1.46 | 0.14 | ||

| SPP 11 | 0.01 | −0.03, 0.07 | 0.50 | 0.66 | 0.50 | ||

| DV1: Peer problems | |||||||

| Step 1 | 16.84 | <0.001 | 0.09 | 0.09 | |||

| Constant | 5.21 | 3.84, 6.59 | 7.45 | <0.001 | |||

| Gender | −0.46 | −0.79, −0.13 | −0.14 | −2.73 | 0.007 | ||

| Age | −0.37 | −0.51, −0.22 | −0.26 | −5.02 | <0.001 | ||

| Step 2 | 8.60 | <0.001 | 0.12 | 0.10 | |||

| Constant | 4.97 | 3.26, 6.68 | 5.71 | <0.001 | |||

| Gender | −0.44 | −0.77, −0.10 | −0.13 | −2.59 | 0.01 | ||

| Age | −0.32 | −0.47, −0.16 | −0.23 | −4.03 | <0.001 | ||

| SOP-Striving 9 | −0.06 | −0.12, −0.006 | −0.13 | −2.15 | 0.03 | ||

| SOP-Critical 10 | 0.01 | −0.03, 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.44 | 0.65 | ||

| SPP 11 | 0.04 | 0.01, 0.08 | 0.15 | 2.48 | 0.01 | ||

| DV1: Prosocial behavior | |||||||

| Step 1 | 9.59 | <0.001 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |||

| Constant | 5.72 | 4.38, 7.16 | 8.15 | <0.001 | |||

| Gender | 0.46 | 0.12, 0.79 | 0.14 | 2.68 | 0.008 | ||

| Age | 0.25 | 0.10, 0.39 | 0.18 | 3.36 | 0.001 | ||

| Step 2 | 5.02 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.06 | |||

| Constant | 4.89 | 3.15, 6.63 | 5.54 | <0.001 | |||

| Gender | 0.50 | 0.16, 0.84 | 0.16 | 2.91 | 0.004 | ||

| Age | 0.23 | 0.07, 0.39 | 0.17 | 2.90 | 0.004 | ||

| SOP-Striving 9 | 0.06 | 0.005, 0.12 | 0.13 | 2.13 | 0.03 | ||

| SOP-Critical 10 | 0.005 | −0.04, 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.83 | ||

| SPP 11 | −0.006 | −0.04, 0.03 | −0.02 | −0.34 | 0.73 | ||

| Step 3 Interactions | 4.29 | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.07 | |||

| Constant | 5.76 | 4.25, 7.27 | 7.50 | <0.001 | |||

| Gender | 0.49 | 0.15, 0.83 | 0.15 | 2.86 | 0.004 | ||

| Age | 0.25 | 0.09, 0.41 | 0.18 | 3.10 | 0.002 | ||

| SOP-Striving 9 | 0.008 | −0.07, 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.84 | ||

| SOP-Critical 10 | 0.008 | −0.03, 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.35 | 0.72 | ||

| SPP 11 | −0.007 | −0.04, 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.39 | 0.69 | ||

| Gender x SOP-Striving | 0.11 | 0.002, 0.21 | 0.16 | 1.99 | 0.04 | ||

| Age x SOP-Striving | −0.03 | −0.08, 0.02 | −0.02 | −1.20 | 0.22 | ||

| DV1: Total difficulties | |||||||

| Step 1 | 4.20 | .01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |||

| Constant | 12.73 | 7.56, 18.01 | 4.81 | <0.001 | |||

| Gender | −1.83 | −3.10, −0.57 | −0.15 | −2.85 | 0.005 | ||

| Age | −0.11 | −0.66, 0.43 | −0.02 | −0.41 | 0.67 | ||

| Step 2 | 4.54 | 0.001 | 0.06 | 0.05 | |||

| Constant | 12.72 | 7.15, 18.29 | 4.49 | <0.001 | |||

| Gender | −1.54 | −2.81, −0.28 | −0.13 | −2.41 | 0.01 | ||

| Age | −0.12 | −0.71, 0.46 | −0.02 | −0.41 | 0.67 | ||

| SOP-Striving 9 | −0.19 | −0.41, 0.03 | −0.10 | −1.64 | 0.10 | ||

| SOP-Critical 10 | 0.22 | 0.05, 0.39 | 0.16 | 2.59 | 0.01 | ||

| SPP 11 | 0.12 | −0.009, 0.26 | 0.12 | 1.83 | 0.06 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Melero, S.; Morales, A.; Espada, J.P.; Fernández-Martínez, I.; Orgilés, M. How Does Perfectionism Influence the Development of Psychological Strengths and Difficulties in Children? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4081. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114081

Melero S, Morales A, Espada JP, Fernández-Martínez I, Orgilés M. How Does Perfectionism Influence the Development of Psychological Strengths and Difficulties in Children? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(11):4081. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114081

Chicago/Turabian StyleMelero, Silvia, Alexandra Morales, José Pedro Espada, Iván Fernández-Martínez, and Mireia Orgilés. 2020. "How Does Perfectionism Influence the Development of Psychological Strengths and Difficulties in Children?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 11: 4081. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114081

APA StyleMelero, S., Morales, A., Espada, J. P., Fernández-Martínez, I., & Orgilés, M. (2020). How Does Perfectionism Influence the Development of Psychological Strengths and Difficulties in Children? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 4081. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114081